Deficits and debt under the President’s budget

There has been a lot of debate about whether the President’s budget improves or worsens the future deficit picture. This is a debate mostly about baselines – what do you assume would happen otherwise? Rather than engaging in that debate here, I am going to look at the results of what the President has proposed.

What would federal deficits and debt held by the public be if the President’s budget were to become law exactly as proposed?

We will look at it both from the Administration’s point of view, and from that of the Congressional Budget Office, which serves as the referee for Congressional legislation. While the two differ in some respects, the fundamental conclusions are the same.

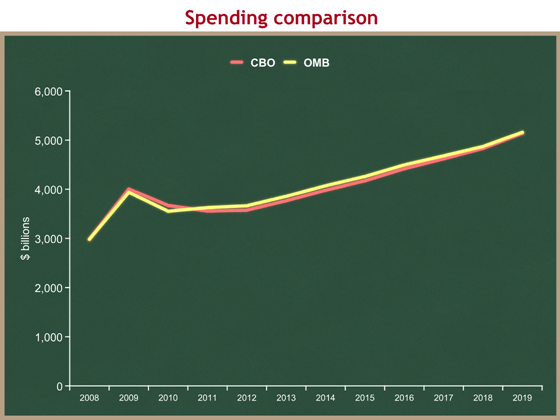

We will begin with spending. You can see from this graph that CBO and OMB agree precisely on how much the President’s budget would spend over the next ten years.

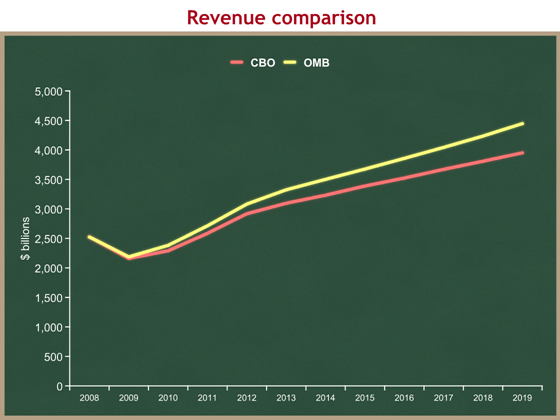

Now we turn to revenues. The President’s budget assumes faster economic growth than does the CBO. A bigger economy leads to more revenues for government, so OMB assumes more revenues from the same set of policies as CBO.

Don’t be fooled by the scale of the graph. That’s a $500 billion difference in 2019.

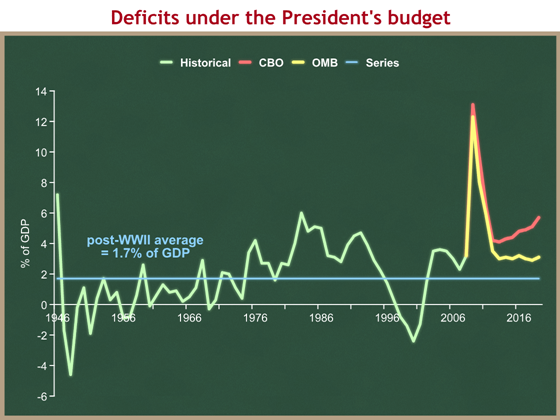

It is this difference in revenue assumptions that leads OMB to have a more optimistic deficit forecast for the President’s budget than CBO. I am going to put the proposed deficits in historic perspective, and switch to % of GDP so we have a fair comparison over a long timeframe.

The light green line shows historic deficits (above the line). The light blue line shows the post-World War II average deficit of 1.7% of GDP. Red is the CBO’s estimate of deficits under the President’s budget, and yellow is the Administration’s estimate. The gap between the two is because of different assumptions about GDP growth leading to different estimates of future federal revenues.

I find it more interesting and worrisome that both estimates show annual budget deficits for the next decade that far exceed historic averages. The Administration’s estimate hovers around 3.0% of GDP, while CBO’s estimate climbs steadily to 5.7% of GDP by the end of the decade. Neither is anything to brag about.

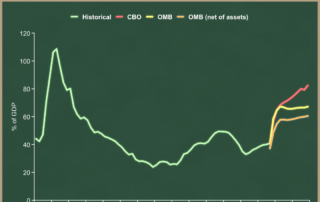

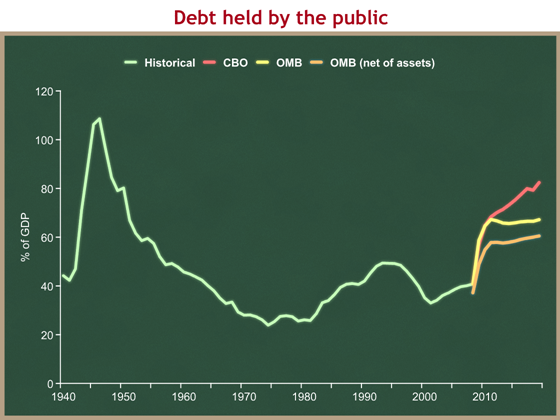

Now let us look at the effects of the President’s budget on debt held by the public.

Again, red is CBO, and yellow is OMB. Orange is Budget Director Peter Orszag’s new net worth measure of debt held by the public, minus the value of financial assets. While interesting, we should not ignore the yellow and red lines. If you borrow money to buy stock, you still are in debt.

No matter which estimate you choose, the conclusion is inescapable: under the President’s budget, debt held by the public will climb to a level not seen since the aftermath of World War II. And in the early 1950s we were paying down debt. Now we will be increasing our indebtedness, just as the federal government begins to expend massive amounts to pay Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid benefits for the Baby Boomers.

In case you’re interested, the last year of this graph is 2019. In that year:

- OMB’s estimate of debt net of financial assets is 60.5% of GDP.

- OMB’s estimate of debt held by the public is 67.2% of GDP.

- CBO’s estimate of debt held by the public is 82.4% of GDP.

Here are my conclusions:

- CBO and OMB differ on their economic assumptions.

- CBO and OMB differ on how they define the baseline (not covered in detail here). This affects the rhetorical debate about whether the President’s budget makes deficits bigger or smaller.

- CBO and OMB basically agree on the qualitative picture of the results of the President’s budget on future deficits and debt. They disagree more about the point of comparison than they do about the result.

- No matter whose economics or baseline you use, the result is terrible for federal deficits and debt over the next ten years, both of which are way above historic averages and not showing any positive trends.

Thanks to Steve McMillin for his help with this post.

CNBC interview this morning

Carl Quintanilla interviewed Former Vermont Governor and DNC Howard Dean and me on CNBC this morning.

We debated health care reform.

You can see for yourself.

Site is back up

This site was down for about 16 hours today, beginning late last night, due to a hardware problem at my hosting service. I am hopeful the problem will not return.

If you notice a few things moving around over the next week, I will be playing with some functionality and layout issues. They will be small enough that you may not notice them.

TV Monday morning

I am scheduled to be a guest on CNBC’s Squawk Box Monday morning, beginning around 7 AM EDT. Former Vermont Governor and DNC Chairman Howard Dean and I will be discussing health care, taxes, and spending.

America’s long-run fiscal problem is spending growth, not taxes

Yesterday I wrote about the history of tax increases since World War II, and about the battle over the total level of taxation. Now I want to turn to spending.

I am a low-tax guy. I have worked on tax issues for 12 of my 15 years in Washington, helping elected officials lower taxes and prevent tax increases. You can see a list of the taxes President Bush cut here. I would like to cut taxes far below where they are today, and I will continue to make the case that America is better off with a bigger private sector and a smaller government. America’s long run fiscal debate, however, is instead principally about whether we will allow future spending increases to force taxes to increase dramatically above where they are today.

I believe that America’s greatest economic policy challenge is the projected long run growth of spending on three programs: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

I would like to show you why I believe this, and how it relates to taxes.

The total tax battle

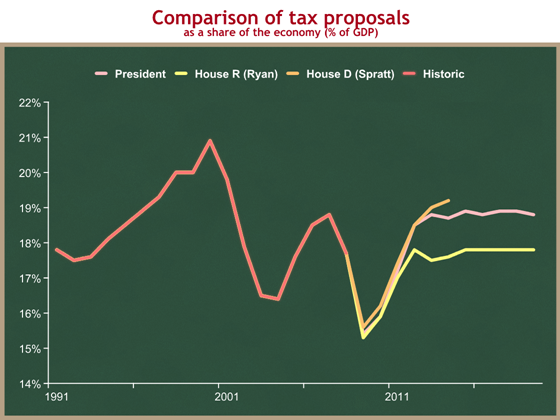

Now that we have reviewed how big a bite the government has taken out of the economy over time, let’s examine the competing tax proposals for the near future.

Revenues are only one element of a budget proposal. For a complete picture of the effect of a budget proposal on the rest of the economy, we should also look at deficits. At the same time, it’s useful to start by understanding how much each budget proposal would take from the economy in total taxes.

We are using the same graph format as before, in which we measure total federal revenues as a share of the economy. Please remember that even a flat line on this graph means the federal government is collecting more taxes in inflation-adjusted dollars each year.

Let’s compare the President’s proposed total federal revenues, with proposals from House Republicans and House Democrats. The House Republican proposal was authored by the ranking Republican on the House Budget Committeee, Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI). The House Democrat proposal passed the House, and was authored by the House Budget Committee Chairman, Rep. John Spratt (D-SC).

From this graph you can see:

- Over the next few years, all three proposals show a steep dip in revenues, followed by a steep increase. This has nothing to do with policy and is entirely about the predicted recession and recovery.

- The President’s budget would have the government take 0.9 percentage points more of the economy than the Ryan proposal. That’s an extra 90 cents out of each $100 of income. This is a fairly steady gap over time.

- The budget passed by House Democrats has higher taxes than even the President’s budget. The House Democrat budget is only a 5-year proposal, so the long run gap could be bigger, but the House is collecting at least another 0.5 percentage points more than the President’s budget. The budget passed by House Democrats means that government will take an additional 50 cents out of each $100 of income above what the President proposed. Compared to the House Republican alternative, the House-passed budget would take an additional $1.40 out of each $100 of income for the federal government. That’s a lot.

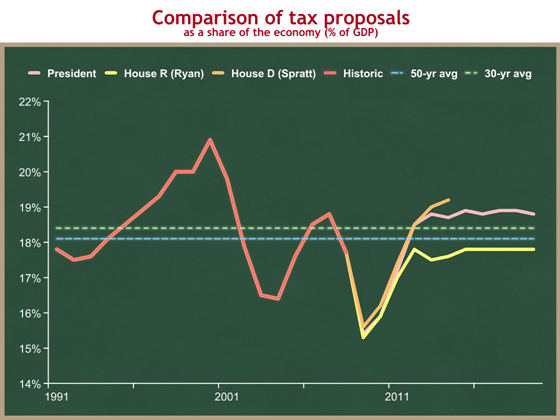

Now let’s compare these proposals to the historic average. I’m a low-tax guy, so I would like to use the post-WWII average of 17.9%. In most discussions, however, the range ends up being between the 50-year average of 18.1%, and the 30-year average of 18.4%. I will include those bounds on this graph, even though my preferred comparison path is a bit lower than the lowest line.

By adding these historic averages, we can see that the House Republican proposal would bring revenues down to a bit below the 50-year historic average. Even under this proposal, the federal government would be getting more inflation-adjusted dollars each year, because a constant percentage still grows in real dollars as the economy grows.

The Obama tax proposal is above the top end of the historic range, and the Democrat House-passed budget is above even that.

A short history of higher taxes

There is always a lot of rhetoric on Tax Day. Later I will comment on some of today’s rhetoric. In this post I will instead focus on some basic facts that are not earth-shattering, but provide some important historic context for the current tax and spending debate.

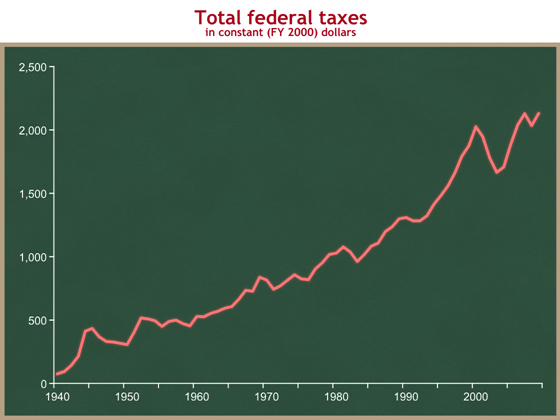

Let’s start by looking at just the total amount of taxes collected by the Federal government over time, adjusting for inflation.

You can see taxes growing fairly steadily over time. The various bumps are a combination of changes in law and economic cycles. Still, even given those factors, the total amount of inflation-adjusted dollars going to the federal government has clearly climbed over time. In real terms, government’s take has gotten bigger.

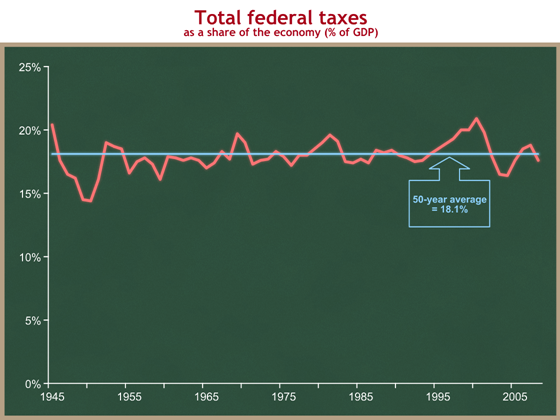

Some argue that we should instead measure total federal taxes as a share of the economy. This presumes that as the economy gets bigger, government “should” get bigger proportionately. I disagree with that view. Some things that government does clearly are related to the size of our population, or are related to other measures of society’s income or wealth. I do not buy that principle as a general matter. Still, let’s look at that perspective.

You can see that the federal government’s take from the economy has remained roughly constant since the end of World War II. The flat line is at 18.1%, and shows that, on average over the past 50 years, Uncle Sam takes about 18.1% out of every dollar earned in America. This graph makes the policy changes and economic fluctuations easier to see. For instance, you can see the effects of the 1993 reconciliation bill (which raised taxes), plus the economic growth of the 90s, ending in the stock market “bubble” (I use that term loosely) in 1999 and 2000 with phenomenally high capital gains revenues, followed by the stock market decline and recession in 2001 and 2002, combined with the effects of the 2001 tax cuts.

There’s actually a slight upward trend to this line. If you look at share of GDP since the end of World War II, the average is 17.9%. If you look over the past 50 years, it’s the 18.1% I have displayed on the graph. Over the past 40 years, it’s 18.3%, and over the past 30 years it’s 18.4%. So there is a creeping upward (measured as a share of the economy), but it’s pretty slow: one or two tenths of a percent of GDP over time. Remember that a flat line on this graph would still represent more real dollars each year going to the federal government.

Still, the overwhelming impression this graph should give you is that of a basic constancy since World War II.

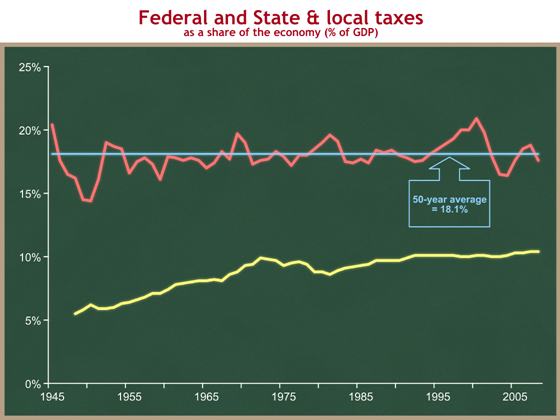

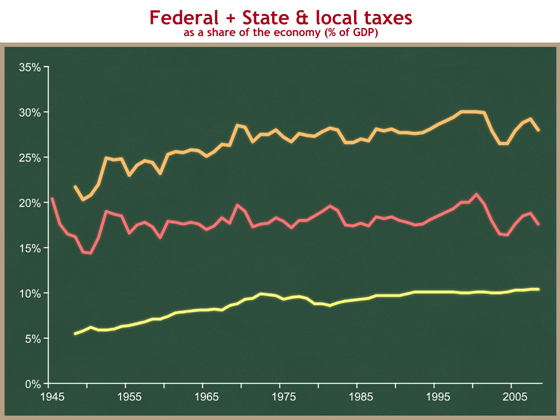

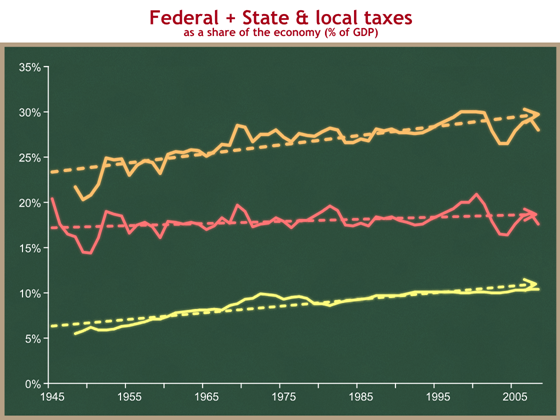

Now let’s add State & local taxes to this graph.

You can see that while Federal taxes have remained roughly constant (with fluctuations), State & local taxes have grown fairly steadily over time, measured as a share of GDP.

Now let’s add the two lines together to see government’s total take from taxpayers. Check out the orange line up top.

It’s a little hard to see the long-term trends on the orange and red lines, but the greatest graphing program ever, Swiff Chart, allows me to add trend lines that make it easier to see.

From this graph, you can see our conclusions:

- Federal taxes have remained roughly constant as a share of the economy since the end of World War II, at just over 18% of GDP (I use 18.1%, others use 18.3%).

- Even if federal taxes remain constant as a share of GDP, total taxes collected by the federal government are going up in real terms.

- In contrast to federal taxes, State and local taxes have grown fairly steadily since 1950.

- So the trend line of government’s take of the U.S. economy is steadily upward since the end of World War II, from around 21% of GDP in 1950 to about 28% now. Seven cents more of each dollar earned are going to government now than in 1950.

Please remember that just-over-18 percent of GDP number from #1. You’re going to need it later.

New York Times to Senator Reid on health care: Speak loudly and carry a little twig

Critical policy fights sometimes happen long before a bill comes up for a vote. Legislative process and strategy intersect early to determine the balance of power for a future vote on policy. Health care legislation is several months away from a floor vote, but the tactical maneuvering has already begun.

Fair warning: we’re going to work through some fairly thick procedural weeds. This is the most in-depth post I have written so far. If you really want to understand the tactical chess of legislating and its enormous effects on policy, you need to know this level of detail. With that caution … <deep breath>

The House and Senate each have passed their versions of the Congressional budget resolution, which sets the procedural rules for spending and tax legislation throughout the year. For these rules to take effect, designees from each body must now work out their differences and produce a common text (a “conference report”) that then passes both the House and Senate. The Congressional budget resolution is an internal management tool of the Congress, and never goes to the President for a signature or veto.

The New York Times argues (“The First Showdown on Health Care“) that Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) and Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D-ND) should put into the budget resolution conference report a Senate reconciliation instruction, to give Leader Reid leverage over moderate Senate Republicans in future negotiations on health care legislation.

If Senators Reid and Conrad do what the Times recommends, then Senate Democrats can in theory, pass a special type of bill, called a reconciliation bill, with only a majority of the Senate. Since the Minnesota Senate seat is still vacant, this means Leader Reid would need 50 of 99 Senators to vote for a health care bill if he uses the reconciliation process. If the budget resolution conference report does not create the process for a reconciliation bill, then he would need 60 votes to overcome any Republican filibuster. There are now 58 Senators who “caucus” as Democrats, including two labeled as Independents, Sen. Lieberman (CT) and Sen. Sanders (VT).

I assume that if he only needs 50 votes to pass a health care bill, Leader Reid will try to start the policy near the left edge of his caucus and then negotiate toward the center as needed to get to 50 votes. The bulk of his caucus is liberal, especially on health care. He will have an eight vote margin to play with, if he limits his universe to just the 58 Democrats and Independents. That gives him a lot of room to maneuver.

If instead he needs 60 votes, he will have to win the support of the most conservative of the 58, and at least two Senate Republicans. Obvious targets would include Senators Snowe and Collins from Maine, or maybe Senator Specter from Pennsylvania.

Thus, I would expect a bill passed under reconciliation to be much farther Left than a bill passed outside of reconciliation. But as we will see in a moment, reconciliation is a limited tool, and cannot be used for every kind of legislative change he might want.

The Times argues that Senator Reid should make sure he has a stick to use against moderate Senate Republicans, in case carrots don’t work. Having this fast-track process in which he would not need their votes would appear to give him and his designees (Sen. Baucus? Sen. Rockefeller? Sen. Kennedy?) leverage in negotiations with those moderates. Note the Times‘ use of the word “weapon”:

Reconciliation is not a weapon that should be deployed immediately. The conferees should agree on language that would allow it to kick in by a date in the fall if the two parties cannot agree on a reform bill. A bipartisan agreement would be nice, but what the country needs right now is effective health care reform.

The Times is imagining a scenario in which Leader Reid would say to moderate Senate Republicans, “I would like to have your votes, and I’m willing to compromise somewhat to get them, but not too much. If you’re not willing to be reasonable, then I will use this reconciliation weapon and pass a more liberal bill without you.”

What does the Times want in this health care reform legislation?

That would make it easier to adopt such important measures as a tightly regulated insurance exchange for those without group coverage, a new public plan to compete with private plans, and mandates that employers contribute to the cost of covering their employees.

The Times wants Leader Reid to wield a stick as he negotiates with moderate Republicans. But if the stick is only a twig, then it will not provide leverage to Leader Reid or his negotiators, and the moderate Senate Republicans are smart enough to know this. The reconciliation threat is effective only if it is a viable path to producing the kind of health care reform that Leader Reid or the Times wants.

The Times hints at why the stick may only be a twig:

The reconciliation approach is not bulletproof. It is primarily designed to deal with spending and revenue issues that affect the deficit. Under current rules, senators can seek to remove any provisions deemed extraneous or “merely incidental” to such budgetary concerns. Nobody is quite sure how the Senate parliamentarian would rule on such items as tighter regulation of private insurers or creation of a new public plan or incentives to improve the coordination of care.

Let’s examine in a bit more detail how the reconciliation rules make this an imperfect weapon for Leader Reid. The Senate reconciliation process is a fast-track procedure that limits the rights of Senators to amend, filibuster, or otherwise delay a bill that they strongly oppose. It is an incredibly powerful legislative tool, created in 1974 as part of a law that comprehensively changed Congressional budget procedures. The law that creates the reconciliation process strictly limits its use to matters that have to do with spending and taxes. (The process exists in the House as well, but I’m going to focus on the Senate where it has a greater effect and is more relevant to the current tactical issue.)

To oversimplify, you can use a reconciliation bill only to change taxes or spending. The process was created to facilitate deficit reduction — various Senate committees would each be given a deficit reduction target, and would be “instructed” by the budget resolution to produce bills that reduced the deficit by those amounts. The Senate Budget Committee would then package all those deficit reduction bills into a single bill, and report it to the Senate floor for debate, amendments, and voting, all under a fast-track process that limits the minority’s ability to filibuster or kill the bill by amendment.

Laws that reduce the deficit either cut spending or raise taxes. Both are politically painful votes for Senators. By combining several smaller deficit reduction bills into a single bill, the reconciliation process was used to create a single bill that reduced the budget deficit by a lot. This gave Senators the excuse to say, “While I oppose the spending cut in section XXX of this bill that would hurt people in my State, the overall benefits of shared sacrifice and deficit reduction make it worth it. I wish

Now any time there is a change of party control in the Senate, advocates for the new majority party argue that reconciliation should be used for everything. If you don’t have the support of 60 Senators to do what you want, then you cry “Let’s put that in reconciliation!” based on a mistaken (or misleading) view that reconciliation can be used to bypass any filibuster or delaying tactic on any type of legislation.

It cannot because of the Byrd Rule, named after Sen. Robert Byrd (D-WV), who included it in the law that originally created the reconciliation process. Basically, the Byrd rule limits reconciliation bills to containing only provisions that turn spending or tax dials. You cannot make broader policy changes that are unrelated to increasing or decreasing spending or taxes, unless you can demonstrate that those policy changes are a “necessary term or condition” of another provision that turns a tax or spending dial. And while this is an exception that lets you include some non-budgetary policies in a reconciliation bill, in practice it is a narrow and limited exception. You cannot in a reconciliation bill make a major non-budgetary policy change if it has a budgetary effect that is “merely incidental” to the scope of the non-budgetary change.

Let us follow the path of the Times’ recommendation, and suppose that the budget resolution conference report were to contain a reconciliation instruction, either to be used to pass health care reform legislation with only 50 votes, or instead to create leverage for Senate Democrats as they negotiate with moderate Senate Republicans (or both).

Now suppose Senate Democrats produced a bill like the Times describes, which created “a tightly regulated insurance exchange for those without group coverage, a new public plan to compete with private plans, and mandates that employers contribute to the cost of covering their employees.”

Creating a new insurance exchange is a policy change that does not affect the federal budget. Sure there would be some expenses for the setup and administration of the exchange (possibly totaling billions of dollars) , but clearly the tax or spending change is incidental to the creation of the new insurance market, which is an enormous policy change by itself. This policy would violate the Byrd rule. If it were included in a final reconciliation bill conference report and there were not 60 Senate votes to waive the Byrd rule, the entire health care reform bill would die. Knowing this, Senator Reid would have no choice but to jettison this policy to avoid jeopardizing the entire bill.

The same is true for an employer mandate. Technically, such a mandate would reduce federal revenues for reasons I won’t get into, but the budgetary effects would again be incidental to the overall policy change proposed. I cannot see how an employer mandate could be included in such a bill and still allow the bill “protected” reconciliation status that would allow Senator Reid to avoid a filibuster.

I think the same is true for the establishment of “a new public plan to compete with private plans,” precisely because it is new. I am less certain of this, and it might depend on how it was written.

The same is true for many other elements of what you would expect in a big health care reform bill. This parliamentary vetting process, which occurs at the very end of a conference negotiation, is called a “Byrd bath.” Budget Committee staff from both sides of the aisle argue their cases to the Senate Parliamentarian. If the Parliamentarian says that a provision violates this rule, then the majority always chooses to remove it rather than risk losing the entire bill. I was the Senate Budget Committee staffer responding for the health portion of the Byrd Bath in the 1995 reconciliation bill, and I helped manage the Byrd Bath process in reconciliation bills in the late 90’s when I worked for Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott.

Returning to the beginning, Senator Reid’s stick is not as big as the Times might like. Yes, he can use reconciliation to expand Medicaid or S-CHIP, or even Medicare, especially if he’s willing to offset those spending increases with spending cuts or tax increases. To the extent he is willing to limit his threat to these areas, reconciliation provides him with leverage.

If, however, he wants health care reform to include the creation of a national health insurance exchange, or employer (or individual) mandates, or other insurance mandates, or a wide range of other health care policy changes that are not principally about taxes or spending, then he won’t be able to use reconciliation to do these things, and he will need moderate Republicans. Those moderate Republicans know that, and should not be fooled if he tries to bluff them.

Speak softly, Mr. Leader. That big stick the New York Times wants you to wield is more like a twig.

Four unpleasant options for TARP funding

Despite Secretary Geithner’s statement to the contrary, I still think the Administration is running out of room within the $700 B Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). In my last four posts on TARP funding (1 2 3 4), I have stuck to what I think I can demonstrate analytically. I am now going to shift to some educated guessing about what may be going on within the Administration that is contributing to confusion on the outside. The prior posts involved math, while now I am analyzing people, so I am far less certain about what you read here than when I walked through the TARP arithmetic.

I think the senior economic policymakers in the Administration are overconstrained and have several bad options in front of them. This is not an unusual situation, but to a certain extent they put themselves into this box by spending TARP money on every problem that popped up. $50 B on housing, $5 B on auto parts suppliers, $15 B on small business loans, additional unspecified sums for GM and Chrysler, and new as well as old mortgage-backed securities — things add up. I think they’re in a box.

The box has three sides:

- They have created expectations among various constituencies for programs announced over the past two months. These expectations would consume most of the remaining $700 B of TARP funds. If their new programs are successful, they will want to expand them to further strengthen financial institutions and markets. If they are unsuccessful, they will need more TARP funds to try something else.

- They are justifiably afraid of asking Congress for more TARP funds.

- They could create some room for themselves by taking taxpayer funds back from some of the healthy big banks, but they may be worried about the signals that sends about the others.

It appears that they are testing all three sides of this triangular box to figure out which is their least worst option.

Senior Administration policymakers are operating in an ever-changing financial, economic, and legislative environment. When they developed the President’s budget in February, asking Congress for more TARP funds probably seemed difficult but not necessarily impossible. In that circumstance, it was reasonable and responsible for them to put a $250 B placeholder in their budget for a potential future TARP request.

The legislative environment is now much more hostile. It would not surprise me if, for the moment, they have ruled out asking Congress for more TARP funds, and are instead trying to figure out how to create as much room as possible within their existing constraint.

Commenter Wayne Marr asked a good question.

… But the main point is that Obama and team (Larry, Christy, Austan, Geithner, etc) can simply go to

[the] well (Congress) since Democrats can pass pretty much what they want. The recovery plan was not named the “Great Bailout:” but the “American Reconstruction and Recovery Plan” or some such nonsense for a reason.Why not another funding program called “The Better Banking Plan for the 21th Century” to provide more cash for technically insolvent banks? Or those that posed a systemic risk? So does it really matter that we have 30B left of TARP or 100B left for TARP?

While I generally agree that the President has tremendous leverage to get Congress to pass his agenda on a wide range of topics, I seriously doubt that is the case here:

- 95 of 235 House Democrats voted no the first time on TARP (on September 29, 2008), and 63 House Democrats voted no on the successful vote four days later. Speaker Pelosi now has a significantly larger majority (254), but she would still need Republican votes.

- TARP is far more unpopular now than last Fall.

- President Obama could undoubtedly get some House D votes who we (the Bush Administration) could not, but not enough to pass such a bill.

- I surmise that House Republicans are in no mood to go out of their way to help the majority or the White House, given how aggressively the Speaker and White House have been in passing other legislation without their input. That does not mean that all of them would vote no, merely that the Administration will have a hard sell to make.

- Finally, even if she had the votes, I would bet heavily against the Speaker bringing up such a bill if she thought the vote would be partisan, because she would conclude that such a vote would expose her House Democrats to too great of a political risk in the next election. I think that she thinks that she would need bipartisan cover from Republicans as a condition for bringing such a bill to the floor.

As background, the Temporary Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) is what the Fed and Treasury are doing together to keep securitization markets going for things like student loans and car loans. They now want to expand it to include securitizations for new mortgages, and to use it to buy toxic mortgage-backed securities. TALF was created during the Bush Administration. This is the second major expansion since President Obama took office.

PPIP is the Public-Private Investment Partnership, Secretary Geithner’s plan to buy toxic assets from banks. It has two parts, one of which works in conjunction with the Fed, and the other with the FDIC.

Secretary Geithner’s comments that they have $135 B of room left in the TARP is testing side #1 of the triangular box to its maximum possible extent. In an attempt to convince people that they have sufficient room, to reassure both markets and the Congress, I think his staff put together the biggest number they could plausibly say with a straight face. They have not, to my knowledge, explained what $135 B of room would mean for the TALF and buying toxic assets, and I fear that such an answer would tremendously disappoint market participants who are expecting a $1+ trillion TALF and a $100 B PPIP. If the Administration has made policy decisions that lock in $135 B of room, then they have scaled something way back beyond what they had previously said publicly.

The Administration faces a choice: scale back these two programs to be smaller than what they had previously suggested to market participants, or squeeze something else hard to create more room within the $700 B limit.

The other option is to get some TARP funds back from the healthiest big banks. Since the law allows the Administration to recycle returned funds for other purposes, every invested dollar repaid can be spent again.

Certain large banks (e.g., JP Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs) are publicly signaling that they would like to repay the Treasury. It is hard to blame them, considering the political and legislative environment. Martha MacCallum of Fox News pushed me on this point, correctly pointing out that it seems un-American to dissuade banks from paying back the taxpayer.

The banks are reportedly being told “not yet” by the Administration. I will guess that the Administration is concerned about something that worried some of our experts — if healthy banks return their funds, then investors will conclude that every bank who is not returning their funds must therefore be unhealthy.

This logic becomes strained, however, when those banks find other avenues for signaling to the market that they are healthy, as they are doing now by screaming “WE WANT TO GIVE IT BACK.”

At some point the banking policy concern may be overwhelmed by the near-impossibility of getting more funding from Congress and the policy and political undesirability of scaling back on PPIP, TALF, or the housing commitment. If this happens, then the Administration will happily start accepting funds from banks. The numbers are large enough that this could create room for them to do other things, and as a long-run policy matter, we want the taxpayer to be paid back. These are supposed to be temporary investments in the banks, in which public capital substitutes for private capital that was unwilling to show up last Fall.

There is another outside-the-box possibility that I am sure the White House has considered. Part of their resource constraint arises from having made a $50 B TARP commitment to housing.

They could push this program out of the TARP, and ask Congress for these housing funds anew. It would be much easier for a heavily Democratic Congress to pass $50 B for housing than for them to pass the same amount (or much more) for “Wall Streeet banks.”

I would oppose such a request, because I oppose this housing spending inside or outside of TARP. But I’m sure they could pass it, given their large partisan majorities in both bodies. This option would cause the White House political pain on its left, which pushed hard for these programs, and could cause FDIC Chairman Bair heartburn, given her impassioned support for these housing programs.

Things probably look a little different to the folks sitting inside the West Wing and at Treasury than I have described here, but I would wager heavily that a discussion at least similar to this is ongoing within the senior ranks of the Administration. As long as that decision is unresolved, it will be confusing as we try to interpret statements like Secretary Geithner’s that he has $135 B of room within the $700 B TARP allocation. Those policymakers need to balance the benefits of decision-making flexibility with the costs and repercussions, from markets and/or Congress, of the bad news when it is eventually delivered. They may be waiting for the right time to signal that a previous commitment will be scaled back, or instead for the right time to ask Congress for more funds. I think it is better for market participants and Congress to have early clarity, especially if it’s bad news.

In my experience, it is better to deliver the bad news as soon as you have made the decision. Rip off the band-aid quickly.

I will end with a thought experiment. Suppose my analysis is roughly correct. It is easy to figure out what you don’t want to do. It is much more difficult to decide what you do want to do. If the President asked you for your recommendation, what would it be?

- Scale back on PPIP and TALF as necessary to avoid having to ask Congress for more funds.

- Ask Congress for more funds. Follow-up: how much more?

- Tell banks that you welcome them repaying the Treasury early.

- Push housing outside of TARP and make a separate request of Congress for those funds.

- Wait and hope.

By focusing only on covering the uninsured, are we solving the wrong problem?

The traditional Beltway logic on health care reform goes like this:

- The problem is that 46 million Americans lack health insurance. (I addressed why this number is incorrect and misleading last Thursday.)

- Government should provide health insurance to those 46 million people, or at least pay for it.

- Let’s expand a taxpayer-subsidized health insurance program to cover the 46 million, or maybe create a new program.

- (Alternately: Let’s mandate that everyone has to buy/have health insurance.)

- This means everyone will have health insurance. We have solved the problem.

Much of the health policy debate centers on how to solve this problem. Liberals want to expand government programs: Medcaid, S-CHIP, Medicare, or the federal employee health benefit program (FEHBP). Conservatives argue that we should instead provide tax incentives to subsidize the purchase of private health insurance.

I fall in the latter camp. My preferred health reform includes taxpayer subsidies for the purchase of private health insurance. But before we jump into the argument about the solution, it is important that we define the problem correctly. Today I would like to challenge the premise that the goal of health reform should be only, or even primarily, to provide taxpayer-subsidized health insurance to those who are uninsured. That defines the problem too narrowly.

Here is my alternate logic:

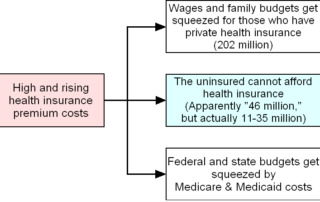

- The problems are (a) health insurance is expensive, and (b) the cost of health insurance grows faster than compensation.

- These two factors (expensive and getting more so) mean that:

- Private health insurance gets more expensive each year for the 202 million Americans who have it. This directly squeezes wages when health insurance is provided by an employer, and household budgets no matter how it is purchased.

- Uninsured people cannot afford health insurance. Those who can just barely afford it this year risk losing it next year and becoming uninsured as their premiums grow faster than their wages.

- Public health insurance expenditures for Medicare, Medicaid, S-CHIP, and FEHBP roughly track private health insurance expenditures over time. High and rapidly-growing health insurance costs therefore crush federal and state government budgets.

- If we can figure out ways to make health insurance less expensive, and/or slow the growth of health insurance premiums, we will solve all three of these problems.

- If our solution slows the growth rate of health insurance premiums, we will have a lasting solution, unlike those solutions which just shift costs from one payor to another (usually, the taxpayer).

Washington focuses on the blue box problem, driven by the phrases “46 million uninsured” and “universal coverage.” In doing so, policymakers often forget that the red box problem is the primary cause of the blue box problem.

I argue that policymakers should try to solve the red box problem, not the blue box problem, for two reasons:

- Solving the red box problem solves the blue box problem of the 11-35 million uninsured. It also helps the 200+ million people who have private health insurance, and it helps solve the #1 problem of federal and state government budgets.

- If you just try to solve the blue box problem, and if you do so by shifting the costs onto someone else (the taxpayer), you will end up chasing your tail, because within a few years the growth of health insurance premiums will put you right back where you started. You will create an additional unsustainable burden on the taxpayer.

Rather than just trying to expand taxpayer-financed health insurance to the uninsured, policymakers should try to understand and address why health insurance is expensive and getting more so each year. If they can address the red box problem, they will solve all three symptoms and create a longer-lasting solution.

My alternate logic may seem trivially obvious. Yet in Washington it is frequently forgotten or ignored.