What if the sequester was a true across-the-board spending cut?

While the sequester is advertised as an across-the-board spending cut, it’s not.

Let’s review:

- The sequester is modeled after a similar provision in law from more than 20 years ago. That earlier sequester exempted certain programs from spending cuts, most notably Social Security, and it limited any Medicare cut to at most

2%4%. These are the two largest entitlement programs in the federal budget. - When the terms of this sequester were negotiated in the summer of 2011, the President’s advisors expanded the list of programs exempt from spending cuts to include most low-income/safety net entitlement programs. Most notable here is the exemption of Medicaid, the third largest entitlement. They also limited the Medicare cut to no more than 2%.

- In the summer of 2011 President Obama wanted the sequester to raise taxes as well but Congressional Republicans refused. For the past few months the President has been trying to rewrite the terms of that deal so that tax increases will be substituted for spending cuts, at least for the first year. His insistence has contributed to a stalemate.

- The sequester is now cutting spending in FY13 by the following percentages:

- defense discretionary: 7.8% cut;

- domestic discretionary: 5.0% cut;

- Medicare: 2.0% cut;

- small pots of defense and domestic mandatory spending are cut by almost the same percentages as their discretionary counterparts above.

tsaLet’s do a thought experiment: suppose the sequester now taking effect was instead structured as a true across-the-board spending cut? Suppose we wanted to cut government spending this year by the same $85 B as is being cut now, but we didn’t exempt huge swaths of entitlement spending? And suppose we cut all spending by the same percentage?

The discretionary programs now being cut by the sequester would take smaller hits. Let’s see how the numbers change.

In my hypothetical across-the-board spending cut I will exempt only interest payments and defense spending in a combat theater. Everything else, including all non-combat theater defense and the three largest entitlements of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid is on the cutting block along with all other non-interest, non-combat spending. And I’m going to cut everything by the same percentage rather than having a higher percentage cut for defense and a lower percentage cut for Medicare.

My arithmetic shows that such a true across-the-board spending cut would save the same $85 B this year through a 2.6% cut to all spending except interest and defense spending in a combat theater.

A true across-the-board spending cut would therefore be about one-third as deep of a cut in defense spending as the current sequester, and about half as deep of a cut in nondefense discretionary spending as the current sequester.

Seniors wouldn’t like a 2.6% cut in their Social Security checks, and the poor wouldn’t like the same percentage cut in Medicaid, cash welfare, food stamps, and other low-income support programs. Medical providers and health insurers wouldn’t like the larger cuts in Medicare and the inclusion of Medicaid and CHIP in the cuts.

But there would be upsides for other things the federal government does relative to where we are now. Let’s look at the effect of this alternative on spending this year for some popular programs relative to the effect of the sequester now in place. If we substituted a true 2.6% across-the-board spending cut for our current sequester, this year the federal government would spend:

- $300M more for Special Education;

- $732M more for medical research at the National Institutes of Health, $138M more for National Science Foundation grants, and $424M more for NASA;

- $124M more for the Food & Drug Administration and food safety;

- $131M more for airport security, $110M more for the FAA, and $23M more for air marshals;

- $333M more for the FBI;

- $139M more for immigration and customs enforcement and $242M more for customs and border protection;

- $53M more to operate the National Parks and $141M more for the Forest Service;

- $24M more for the Smithsonian;

- $54M more for child are and development block grants, and $238M more for children and families services programs;

- $195M more for global health programs;

- $142M more for the Coast Guard;

- and about $27B more for defense.

By insisting that the deficit reduction debate is a choice between cutting spending and raising taxes the President has frozen Washington in a stalemate position that is likely to last for the remainder of his term. If policymakers were instead to set the tax stalemate aside and examine more closely the choices they are implicitly making within the universe of government spending, they would see that by exempting huge swaths of popular entitlement spending from any cuts they are focusing the pain on programs that to many are more important and more popular.

Our federal budget process is fouled up in that it gives procedural advantages to entitlement spending over discretionary spending. Benefit programs that primarily help particular individuals are advantaged, while programs that principally provide for the common good are disadvantaged. The current sequester exacerbates those procedural advantages and, as a result, means that many broadly-supported functions of government are being cut even more that they would be if the spending cuts were distributed evenly across all government spending.

(photo credit: Anita Ritenour)

A flawed attempt to assign blame

Yesterday I mentioned that the President now has a new target for blame any time there’s a piece of economic bad news. Here he is last Friday.

THE PRESIDENT: So economists are estimating that as a consequence of this sequester, that we could see growth cut by over one-half of 1 percent. It will cost about 750,000 jobs at a time when we should be growing jobs more quickly. So every time that we get a piece of economic news, over the next month, next two months, next six months, as long as the sequester is in place, we’ll know that that economic news could have been better if Congress had not failed to act.

And let’s be clear. None of this is necessary. It’s happening because of a choice that Republicans in Congress have made. They’ve allowed these cuts to happen because they refuse to budge on closing a single wasteful loophole to help reduce the deficit. As recently as yesterday, they decided to protect special interest tax breaks for the well-off and well-connected, and they think that that’s apparently more important than protecting our military or middle-class families from the pain of these cuts.

The President’s initial attempt to blame Republicans in Congress for current and future economic weakness is flawed because House Republicans passed a bill that would have the same macroeconomic effect as the President’s proposal, at least for this year.

CBO estimates the sequester will knock about 0.6 percentage points off the growth rate of GDP in calendar year 2013, and therefore that undoing the sequester (in 2013) would increase GDP growth by the same amount. For the moment I’ll set aside the concerns often expressed on the right about estimating the GDP effects of fiscal expansion or contraction and take CBO’s estimates as given.

The key flaw in the President’s argument is that the first year effects of the House-passed sequester replacement bill and the Senate Democrats’ failed bill are nearly identical. Each would unwind almost all of the 2013 effects of the sequester, and each would therefore increase GDP growth by the same amount.

The proposals differ in the amount and composition of their deficit-reducing offsets, but in both proposals those would be spread out over a long timeframe beginning next year. Senate Democrats proposed to offset in future years all of the $85 B they would spend this year, while House Republicans passed a bill that would reduce the deficit even more in future years. But $8 B (Senate Democrats) to $20 B (House Republicans) of deficit reduction for each of the nine years after this one is too small to show up in any estimate of macroeconomic effects. The competing proposals would have the same growth benefit this year, and similar and trivially small growth costs in future years, beginning in 2014.

The President says there wasn’t a deal because Republicans refused to accept his proposed offsets. House Republicans can make exactly the same argument. This 0.6 percentage point growth drag is because the two sides couldn’t agree, not because one party wanted to fix the problem and the other party didn’t.

I expect the President will fail to mention that CBO also says that the tax increases he championed and got will slow this year’s economic growth by an additional 0.6 percentage points this year on top of the effects of the sequester.

Skynotfall

Here are a few points on the sequester I haven’t seen elsewhere or I think deserve special emphasis.

Sequester replacement was mostly for show

As best I can tell there were no negotiations across the partisan aisle on how to replace the sequester. The President did some campaigning outside of Washington. Even if he had expected Congressional Republicans to fold to this pressure, his team was not doing the staff-level work needed to actually make legislation happen. And while leaders of both parties claim to hate the sequester, neither side hated it enough to be willing to even begin negotiations over how to pay for its replacement. The competing sequester replacement plans and the rhetoric on both sides look like they were mostly for public positioning and Member management within the Congressional caucuses rather than serious attempts to change the law.

Why the sequester will hold

There are two distinct legislative coalitions that in theory could unwind the sequester. In both hypothetical coalitions cuts in both defense and non-defense discretionary spending would be unwound.

One would be a center-left alliance formed by pro-defense spending Republicans agreeing to raise taxes and cut farm subsidies. These Republicans would be deciding that avoiding defense spending cuts is more important than preventing additional tax increases.

The other would be a center-right alliance formed by Democratic appropriators agreeing to drop their party’s tax increase demands and pay for higher discretionary spending offset entirely by entitlement spending cuts. These Democrats would be deciding that they care more about spending money than about extracting more from the rich.

These coalitions will never form as long as the sequester issue is being controlled by the President and the four Congressional leaders. Each of these five is working principally to hold his or her party intact, and each has so far succeeded. A coalition to replace the sequester would have a chance only if the issue were being handled below the leadership level, most likely in the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. In these committees everyone’s priority is to increase discretionary spending and both sides would be more likely to show flexibility on offsets. Since the issue remains squarely in the hands of the President and the party leaders I expect the sequester will hold indefinitely.

In addition, the optical damage of the cuts affects only the next seven months. If the continuing resolution extends post-sequester spending levels, then the implementation of next year’s sequester won’t show up as a “spending cut,” but instead as a slight increase (say, +2% for inflation) from this year’s spending levels. To the extent the political and press blowback from cutting spending arises from the optics of a decline in spending, that decline takes effect only this year. After that it’s built into the baseline, at least in a political sense.

Watch the CR for spending flexibility and maybe a little money

I instead expect the appropriators to instead pursue more modest versions of the same goals through quietly shaping the upcoming Continuing Resolution. The appropriators appear poised to give targeted flexibility to the Administration in a few limited areas where they agree that the sequester will impose too much pain, and they might even try to shift a few billion dollars around here and there. The Administration claims they are still opposed to funding flexibility. I think they’re irrelevant on this point and the Appropriators will now quietly exert process and legislative language control to minimize the policy harm from the sequester. And the more flexibility the appropriators provide, and the more they shift funds (within what I hope is a fixed post-sequester topline) to address sequester-driven policy harm, the more likely the sequester will be sustained over time.

The White House’s management challenge

While Team Obama now says the sky will now drop gradually rather than fall suddenly, they are sticking to their line that the pain from these spending cuts will be intolerable and will/should force Congress to increase taxes and discretionary spending.

With this argument they create a management challenge for themselves. They need the harm from these cuts to be severe and visible. The more harm is done and felt, the more likely that Republicans will relent to the president’s position (or so goes this logic). More policy harm creates more legislative pressure.

But the TSA manager at O’Hare or Logan or LaGuardia wants to minimize policy harm in his area, not maximize it. Sure he’d like more funding, but from his perspective there’s little he can do to influence Congress on something as big as the sequester. And since he will personally take the public heat for long security lines in his airport, his goal is to make do as best he can and minimize the harm done by the cuts.

The same is true for every program manager throughout the government. Each is judged on how well her program meets its goals given the funding available. If we simply assume that these managers will try to do their jobs as effectively as possible, both for noble policy reasons and for personal reputational reasons, then they will be working at odds with the President’s strategic goal of maximizing visible harm to undo the sequester. They will be trying to minimize the damage done while the President wants the opposite.

Playing a longer game?

It is possible the President’s primary goal is not to replace the sequester with offsets that he prefers. Sure he’d prefer that policy outcome, but it’s hard to believe that he and his team were so clueless that they actually thought his recent barnstorming would cause Republicans to fold and agree to raise taxes. Again.

Charles Krauthammer has suggested the President is instead playing a longer game, that his strategic goal is instead to win Democratic majorities in 2014 rather than to win a tactical victory by extracting a few tens of billions of dollars now from the House Republican majority. If Mr. Krauthammer is right, then the goal of barnstorming is to further damage the Republican brand rather than to enact legislation in the short run.

The other obvious benefit to the barnstorming is that without a deal to replace the sequester, the President now has a new target for blame-shifting in his macroeconomic message.

- Old message: All economic bad news is George W. Bush’s fault, all good news is because my policies are working.

- New message: All economic bad news is Congressional Republicans’ fault, while all good news is because my policies are working.

Both these “long game” explanations are dispiriting. That doesn’t mean they’re wrong.

The deficit does not measure the size of government

In his State of the Union Address President Obama said:

Let me repeat – nothing I’m proposing tonight should increase our deficit by a single dime. It is not a bigger government we need, but a smarter government that sets priorities and invests in broad-based growth.

Let’s set aside for the moment the question that others have raised, the credibility of his claim that his proposals will not increase the deficit. Even if the President’s new proposals don’t increase the deficit they will still make government bigger because they increase government spending.

The deficit does not measure the size of government. It instead measures how economic resources are allocated over time to finance government spending. When we increase the deficit we reallocate some future income to today for government to spend. When we reduce the deficit we are taking less future income to pay for today’s government spending.

When the President says he won’t increase the deficit, he is saying he will not increase the amount of future income taken to pay for increased government spending today. In effect he is promising not to create an additional burden to raise future taxes beyond what’s in current law. He is not saying he won’t increase government spending today and raise current taxes by an equal amount, which is what we mean by government getting bigger.

As a fiscal matter we should measure the size of government by the amount government spends, not by the difference between what it collects and what it spends (the deficit). Suppose in our $16 trillion economy you were to increase government spending by $320 billion per year and increase taxes by the same amount. The deficit would be unchanged but government would be $320 billion per year bigger.

For the 50 year period before the 2008 financial crisis total federal government spending averaged 20.1% of GDP. CBO tells us it’s 22.2% this year and projects that under current law it will average 22.1% over the next decade. That means the federal government is and will continue be 10% bigger than it his has historically been, relative to the economy. If we were to use real dollars rather than percent of GDP we’d measure an even bigger increase. As a fiscal matter the federal government is and will be significantly bigger than it has historically been.

If you increase government spending you make government bigger, even if you pay for that spending with higher taxes. To make government smaller, cut government spending.

In addition to fiscal expansion the federal government has also massively increased its regulatory scope in the past four years, especially in health care and financial services. The President proposes that in the next four years he’ll do the same to the energy sector.

President Obama is correct that we don’t need a bigger government. Unfortunately, that is what has resulted from his first term and what he proposes for his second.

Not catching up

This is not a happy post.

Each year the federal budget cycle begins with release of the baseline from the Congressional Budget Office in a document titled The Economic and Budget Outlook. If you want to learn more about economic and fiscal policy I recommend you read carefully at least CBO’s short summary.

My former White House colleague Charles Blahous wrote a great piece that highlighted ten fiscal policy lessons you should draw from CBO’s latest baseline report. With this post I’d like to look at one important macroeconomic graph from that same report.

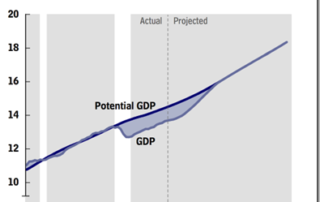

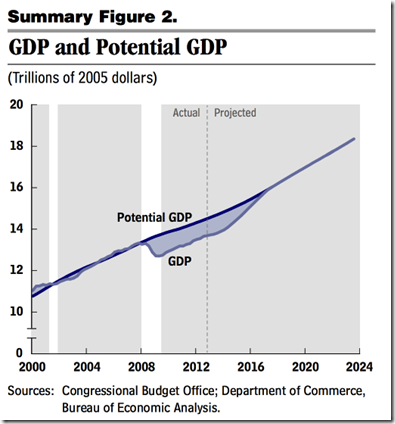

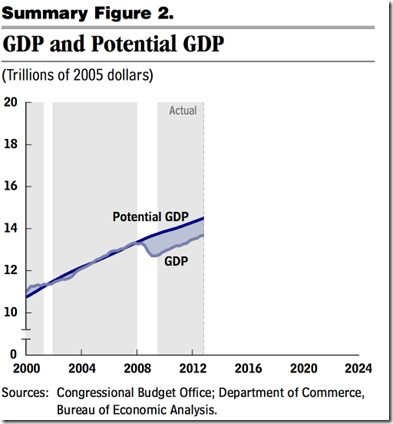

This graph compares actual GDP with what GDP would be “if everyone were working,” a rough description of what the economists call potential GDP. They estimate the lowest unemployment rate that they think would be consistent with inflation not accelerating. CBO thinks this number is 5.5%. They then estimate what economic output would be if we were at 5.5% unemployment rather than where we are, which is now 7.9%.

The gap between the light blue (actual GDP) and dark blue (potential GDP) lines above therefore represents an estimate of the output lost due to high unemployment. To the left of the dotted line that output gap is in the past and cannot be recovered. To the right of the dotted line we see CBO’s projections for actual and potential GDP in the future. We want actual GDP to converge with potential GDP, to “close the gap” quickly.

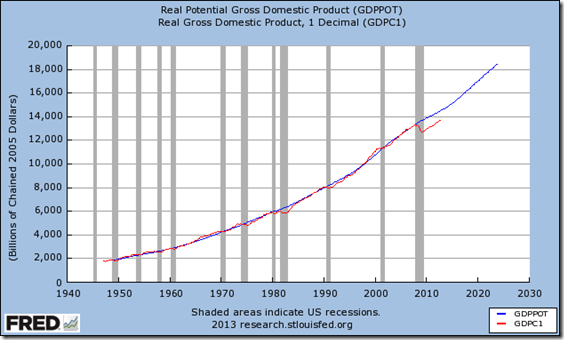

Now let’s zoom out and look at a similar historical graph measured in decades rather than years.

From this graph we can see that in the long run, actual GDP tracks closely with potential GDP, and that the recent output gap is quite large in comparison.

Let’s zoom back in and examine the recent past, the left half of CBO’s graph.

The downward sloping part of the light blue line is the recent recession, also marked by the vertical white stripe. If you look closely you can see actual GDP flattening out in early 2008 as potential GDP continues to rise. Actual GDP then plummets as the financial shock hits in the second half of that year. The recession ended and the recovery began where the line started sloping upward in mid 2009.

In trying to frame this story positively President Obama draws your attention to the fairly steady growth of actual (real) GDP since the recession ended, the upward slope of the light blue line from mid 2009. This graph also shows that in recent years actual GDP had been growing at roughly the same rate as potential GDP. Because the light blue and dark blue lines have almost the the same slope, the distance between them is almost as large now as it was when the recession ended. So while the President is right that the economy has been growing for 3+ years, the output gap is almost the same size as it was in mid 2009. We’re not catching up.

Here is how CBO describes it.

By CBO’s estimates, in the fourth quarter of 2012, real GDP was about 5½ percent below its potential level. That gap was only modestly smaller than the gap between actual and potential GDP that existed at the end of the recession because the growth of output since then has been only slightly greater than the growth of potential output.

To close the output gap we need much faster short-term economic growth than we have had over the past three and a half years. We need the light blue line to slope sharply upwards until it meets up with the dark blue line.

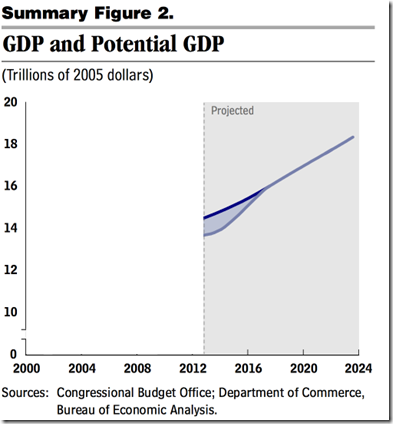

Now let’s turn to CBO’s projection for the future. I’ll hide the left half of the graph this time.

Now we can see more closely that CBO’s GDP projection has three significant features:

- CBO projects that real GDP will continue to grow only as fast as potential GDP this year;

- They then project that growth will accelerate; but

- They project that the output gap won’t close until the end of 2017, almost five years from now.

Attaching numbers to this, CBO projects real GDP will grow 1.4 percent in 2013, 3.4 percent in 2014, and 3.6 percent per year from 2015-2017, reaching potential GDP at the end of 2017.

This translates into their (un)employment projections as well. CBO projects an 8.0% unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of this year and a 7.6% rate at the end of 2014, only three-tenths of a percentage point below where we are now. They then project that the unemployment rate will decline to reach full employment by the end of 2017.

On our current path CBO projects we won’t reach full employment for almost five more years.

CBO also estimated the total size of the output gap and it’s depressing:

With such a large gap between actual and potential GDP persisting for so long, CBO projects that the total loss of output, relative to the economy’s potential, between 2007 and 2017 will be equivalent to nearly half of the output that the United States produced last year.

You may have noticed that I have avoided discussion (here) of why the economy has grown so slowly, how much of that is because of or in spite of policy decisions, and why it’s projected to continue to do so for the next year. That’s where the food fight begins, including the debate about whether and how much the 2009 fiscal stimulus increased growth, and the debate about how much of slow future growth is because of business uncertainty about the economy, about drags from policy and regulation, and about allowing more time for balance sheet repair after the financial shock of 2008.

Those are incredibly important debates but today I just want to highlight the basic historic facts and a mainstream projection from an unbiased source. On our current policy path CBO projects continued slow growth for 2013 and a gradual acceleration after that, returning the U.S. economy to full capacity output by the end of 2017. That projection excludes:

- the downside risk to growth from policy shocks like further tax increases proposed by the President, repeated unresolved fiscal conflicts that exacerbate business uncertainty, and additional regulatory burdens rumored to be coming from HHS, IRS, EPA and financial regulators; and

- the downside risk to growth from possible external shocks from a possible Middle East crisis or a sudden unraveling of Europe’s financial system.

I told you this wasn’t a happy post.

Summary

- While the U.S. economy has been growing fairly steadily since the recession ended in mid 2009, it has been doing so far more slowly than we need. Actual growth has been just sufficient to keep up with growth in our national economic capacity.

- CBO projects that 2013 will be yet another year of slow growth with acceleration beginning in 2014. They project we won’t reach full employment until the end of 2017, almost five years from now.

- CBO estimates that the total lost economic output over the decade will be equal to the entire U.S. economic output for half of last year.

Why stop at $9? A $90 minimum wage

Tonight President Obama proposed increasing the minimum wage from $7.25 per hour to $9. Here is his argument from tonight’s State of the Union address (emphasis is mine):

We know our economy is stronger when we reward an honest day’s work with honest wages. But today, a full-time worker making the minimum wage earns $14,500 a year. Even with the tax relief we’ve put in place, a family with two kids that earns the minimum wage still lives below the poverty line. That’s wrong. That’s why, since the last time this Congress raised the minimum wage, nineteen states have chosen to bump theirs even higher.

Tonight, let’s declare that in the wealthiest nation on Earth, no one who works full-time should have to live in poverty, and raise the federal minimum wage to $9.00 an hour. This single step would raise the incomes of millions of working families. It could mean the difference between groceries or the food bank; rent or eviction; scraping by or finally getting ahead. For businesses across the country, it would mean customers with more money in their pockets. In fact, working folks shouldn’t have to wait year after year for the minimum wage to go up while CEO pay has never been higher. So here’s an idea that Governor Romney and I actually agreed on last year: let’s tie the minimum wage to the cost of living, so that it finally becomes a wage you can live on.

If raising the minimum wage is good economic policy, why stop at $9 per hour? Why not increase it to $90 per hour? By the President’s logic, doing so would dramatically increase the income of not just millions of working families, but tens of millions of working families, and indeed of almost all working Americans.

By the President’s logic, a $90 minimum wage would be good for American businesses because their customers would have more money in their pockets. A full-time worker making the minimum wage wouldn’t make $18,000 per year as the President proposes, but $180,000 per year.

I am, of course, joking, and in doing so I’m trying to demonstrate the flawed logic of a minimum wage increase of any size. In my example a typical worker whose labor is worth $20 per hour to his employer would not suddenly find himself being paid $90 per hour. He would find himself laid off because his employer would choose not to employ him rather than to pay a wage more than the value the worker produces for the firm. Since almost all Americans produce less than $180,000 of value per year for their employer, layoffs would skyrocket. Customers of American businesses would not have more money to spend, they’d have much less because they’d be unemployed.

The same logic holds, just to a much lesser degree, for a minimum wage increase of any size, including the increase to $9 proposed tonight by the President. A minimum wage increase precludes employers from hiring, or from continuing to employ, those workers whose productive value to the firm is worth less than the new minimum wage. Like any price ceiling or price floor a minimum wage restricts supply, and an increase in the minimum wage restricts supply more. Raise the minimum wage and you will eliminate jobs for the lowest-skilled workers in America.

Who are the lowest-skilled workers? Many of them are teenagers, new immigrants, and high school dropouts. They would be the most harmed by a minimum wage increase.

Minimum wage increases are politically attractive because they sound like they’re going to help poor people and because the economic argument against it takes a little time and effort to explain. When pressed, proponents of raising the minimum wage argue that it wouldn’t reduce the number of available jobs that much because even the lowest-skilled workers are worth more than the proposed higher minimum wage. Or they argue that when the minimum wage has been increased in the past, they couldn’t find evidence that employment declined. It’s absurd to argue that a policy is good because “we don’t think it will do much harm,” or “we couldn’t find evidence of harm when we did this policy before.”

Another version of this argument is that because the minimum wage is not indexed to inflation, the real (inflation-adjusted) minimum wage declines over time without new legislation to raise it. But if the real minimum wage does decline, then a few more of the even lowest-skilled workers will now have job opportunities available to them.

No matter how hard they try, Congress can’t outlaw economics any more than they can outlaw gravity. Congress should reject the President’s proposal and in doing so maximize job opportunities for teenagers, high school dropouts, new immigrants and other low-skilled workers.

(photo credit: Ed Yourdon)

The President’s sequester remarks, annotated

My annotations follow each portion of the President’s remarks on the sequester today.

THE PRESIDENT: Good afternoon, everybody.

I wanted to say a few words about the looming deadlines and decisions that we face on our budget and on our deficit — and these are decisions that will have real and lasting impacts on the strength and pace of our recovery.

Yesterday was the legal deadline for the President to submit his budget to Congress. Not only did he miss the deadline again this year, but his team has given no indication of when they will meet this legal requirement.

In these remarks the President proposes to delay immediate spending cuts and substitute a combination of (future, I think) spending cuts and tax increases. Even if you believe this will have a “real” effect on our recovery, it won’t have a “lasting impact” on it. A temporary loosening of fiscal policy would, at most, temporarily goose economic growth. That’s not “lasting.”

THE PRESIDENT: Economists and business leaders from across the spectrum have said that our economy is poised for progress in 2013. And we’ve seen signs of this progress over the last several weeks. Home prices continue to climb. Car sales are at a five-year high. Manufacturing has been strong. And we’ve created more than six million jobs in the last 35 months.

And GDP was flat last quarter … and the unemployment rate ticked up last month. 6M / 35 = +171K jobs/month, which when unemployment is high is nothing to brag about. “Our economy is poised for progress” is what you say when you can’t say “our economy is growing now.”

THE PRESIDENT: But we’ve also seen the effects that political dysfunction can have on our economic progress. The drawn-out process for resolving the fiscal cliff hurt consumer confidence. The threat of massive automatic cuts have already started to affect business decisions. So we’ve been reminded that while it’s critical for us to cut wasteful spending, we can’t just cut our way to prosperity. Deep, indiscriminate cuts to things like education and training, energy and national security will cost us jobs, and it will slow down our recovery. It’s not the right thing to do for the economy; it’s not the right thing for folks who are out there still looking for work.

He argues that the past drawn-out process caused uncertainty which hurt consumer confidence. He recently made a similar argument against a short-term debt limit extension. But eight paragraphs from now he proposes to delay the sequester, further “drawing out” that process, to allow time to substitute different spending cuts and tax increases for the sequester. By his own logic, his proposal should further hurt consumer confidence.

I’m not sure how to respond to his point that immediate government spending cuts cause economic harm, because he has no proposal to tell us what he wants instead. If he proposes to change the mix of deficit reduction (more tax increases and defense spending cuts, fewer nondefense spending cuts) but not the timing, then all he’s doing is shifting resources from the private to the public sector, and from one part of government to another. That’s going to have no short-term growth effect and will hurt long-term growth because the private sector is smaller.

If instead he wants to substitute future deficit reduction for that which is about to begin March 1, then he is, in effect, arguing that given a weak economy, our budget deficit this year ($845 B or 5.3% of GDP) isn’t big enough. This is a traditional Keynesian fiscal stimulus argument. But his problem is that the numbers are too small: the sequester will cut spending this calendar year by about $65 B. Even if you push all that deficit effect into future years, you’re not going to move the needle much on a $16 T economy.

The deep indiscriminate cuts to which he refers are the result of the sequester that his advisors proposed to Congress in July of 2011 and which he signed into law that August.

And he argues that cutting government spending now would harm the economy and “folks who are out there still looking for work,” but his solution means that government employees would be protected from job loss while those previously employed in the private sector had to suffer the pain of a weak labor market. That doesn’t seem fair.

THE PRESIDENT: And the good news is this doesn’t have to happen. For all the drama and disagreements that we’ve had over the past few years, Democrats and Republicans have still been able to come together and cut the deficit by more than $2.5 trillion through a mix of spending cuts and higher rates on taxes for the wealthy. A balanced approach has achieved more than $2.5 trillion in deficit reduction. That’s more than halfway towards the $4 trillion in deficit reduction that economists and elected officials from both parties believe is required to stabilize our debt. So we’ve made progress. And I still believe that we can finish the job with a balanced mix of spending cuts and more tax reform.

He’s got a small verb tense problem and a large logic problem here. Policymakers have cut the deficit by less than $100 billion so far, and they have enacted policies which, if not unraveled by future laws, would result in another $2.4ish trillion in deficit reduction over the next nine years. But all these future savings are from cutting discretionary spending, which is what the President is (ambiguously) proposing to undo here. It seems a bit hypocritical to simultaneously claim credit for enacted future cuts in discretionary spending at the same time you propose to undo them. The President would have more credibility here if he were proposing specific spending cuts and tax increases to substitute for the spending cuts he wants to undo. But the only thing he is specific about is that he wants to undo or delay the impending spending cuts.

THE PRESIDENT: The proposals that I put forward during the fiscal cliff negotiations in discussions with Speaker Boehner and others are still very much on the table. I just want to repeat: The deals that I put forward, the balanced approach of spending cuts and entitlement reform and tax reform that I put forward are still on the table.

But what exactly are those proposals, and will the President propose them in his budget? If he is willing to use a chain-weighted CPI for COLAs and tax bracket indexation, will he propose it? If he is willing to raise the eligibility age for Medicare, will he propose it? If not, how do we know what he is actually proposing? By reading Bob Woodward’s book and background quotes from unnamed senior advisors in POLITICO? He has never told us what this deal is that he put forward, nor has he proposed it to anyone other than Speaker Boehner. If you think it’s good policy, Mr. President, then put it in your budget.

Also, the deal in December has to be modified, right, since a new law enacted $600+ B of current and future tax increases? So technically the deal the President put forward then at a minimum has to be updated to reflect the new law, right?

THE PRESIDENT: I’ve offered sensible reforms to Medicare and other entitlements, and my health care proposals achieve the same amount of savings by the beginning of the next decade as the reforms that have been proposed by the bipartisan Bowles-Simpson fiscal commission. These reforms would reduce our government’s bill — (laughter.) What’s up, cameraman? (Laughter.) Come on, guys. (Laughter.) They’re breaking my flow all the time. (Laughter.)

He mentions only one of the Big 4 entitlements. He and his party slowed Medicare spending growth in 2010, but then they turned around and spent those savings on a new health entitlement. Now he proposes again slowing Medicare spending growth, but ignores the other three sources of medium-term spending growth: Social Security, Medicaid, and the new health subsidies from the Affordable Care Act.

THE PRESIDENT: These reforms would reduce our government’s bills by reducing the cost of health care, not shifting all those costs on to middle-class seniors, or the working poor, or children with disabilities, but nevertheless, achieving the kinds of savings that we’re looking for.

Translation: He’ll cut medical provider payments rather than raise copayments, deductibles, or premiums.

THE PRESIDENT: But in order to achieve the full $4 trillion in deficit reductions that is the stated goal of economists and our elected leaders, these modest reforms in our social insurance programs have to go hand-in-hand with a process of tax reform, so that the wealthiest individuals and corporations can’t take advantage of loopholes and deductions that aren’t available to most Americans.

Translation: I’m not touching the big entitlements unless Republicans raise taxes (again, more) at the same time.

I disagree that his proposals “achieve the kinds of savings we’re looking for,” and that “the full $4 trillion in deficit reduction” is the right target, given that his stated goal is only to get the deficit down to 3% of GDP for the next decade. We need more savings now to start reducing debt/GDP, and we need long-term spending cuts for when entitlement spending growth is otherwise projected to explode. We need much more than $4 trillion of deficit reduction over the next decade, and it’s incorrect to suggest that there is a consensus among elected leaders on that point.

The “loopholes and deductions that aren’t available to most Americans” language is new to me. I wonder what he means? Tax deductions have greater dollar value to a high-income taxpayer than to “most Americans,” but both taxpayers have these preferences “available to them.”

THE PRESIDENT: Leaders in both parties have already identified the need to get rid of these loopholes and deductions. There’s no reason why we should keep them at a time when we’re trying to cut down on our deficit. And if we are going to close these loopholes, then there’s no reason we should use the savings that we obtain and turn around and spend that on new tax breaks for the wealthiest or for corporations. If we’re serious about paying down the deficit, the savings we achieve from tax reform should be used to pay down the deficit, and potentially to make our businesses more competitive.

Here’s the President’s position, as best I can infer:

- Raising taxes to offset tax cuts: Bad;

- Raising taxes to reduce the deficit: Good but he’s not proposing it;

- Raising taxes to increase spending: He’s proposing it while pretending he’s doing #2.

He argues that raising taxes to reduce future deficits is a good thing, but as I understand it he wants to raise taxes to pay for more government spending (by undoing the spending sequester). That’s quite different.

THE PRESIDENT: Now, I think this balanced mix of spending cuts and tax reform is the best way to finish the job of deficit reduction. The overwhelming majority of the American people — Democrats and Republicans, as well as independents — have the same view. And both the House and the Senate are working towards budget proposals that I hope reflect this balanced approach. Having said that, I know that a full budget may not be finished before March 1st, and, unfortunately, that’s the date when a series of harmful automatic cuts to job-creating investments and defense spending — also known as the sequester — are scheduled to take effect.

I don’t blame the American people for agreeing with the President; he is personally popular and it is impossible for them to understand what he is proposing. He has never publicly described or proposed the deals he privately offered to Speaker Boehner. He hasn’t proposed a budget this year and doesn’t appear likely to do so soon. He calls government spending “investment,” tax increases “tax reforms,” and welfare payments “tax cuts.” He keeps shifting baselines against which he measures “balance” and he repeatedly conflates taxes and spending. I have been studying and working on fiscal policy for more than 15 years and I can barely understand what he’s saying. No wonder the American people are confused and frustrated.

He says, “I know that a full budget may not be finished before March 1st”:

- He missed the statutory deadline for proposing a budget and is creating further delays and uncertainty by not even announcing when he will propose a budget, complicating the jobs of both the House and Senate budget chairmen.

- The (often missed) deadline for a budget resolution conference report is April 15th.

- So it’s unfair to suggest that Congress is somehow failing by not finishing a full budget by the March 1 sequester deadline.

THE PRESIDENT: So if Congress can’t act immediately on a bigger package, if they can’t get a bigger package done by the time the sequester is scheduled to go into effect, then I believe that they should at least pass a smaller package of spending cuts and tax reforms that would delay the economically damaging effects of the sequester for a few more months until Congress finds a way to replace these cuts with a smarter solution.

Who in Congress is seriously discussing now “acting immediately on a bigger package?” Anyone? The Grand Bargain died on New Year’s Day with the enactment of a $600+ B tax increase. This is another straw man so that the President can repeatedly say “I’m for a big deal” while making no new concessions to get one done nor taking any steps to create an environment in which such a deal might happen. The “if” clause above is therefore trivially true. The President is saying Congress should replace or delay the sequester for a few months but he offers no specific proposal to do so.

THE PRESIDENT: There is no reason that the jobs of thousands of Americans who work in national security or education or clean energy, not to mention the growth of the entire economy should be put in jeopardy just because folks in Washington couldn’t come together to eliminate a few special interest tax loopholes or government programs that we agree need some reform.

Yes, there is: Because if you enact a law now that raises taxes now and promises to cut future spending, what is to say that those future spending cuts won’t again be delayed, just as the President is proposing to do now? Also, shifting resources from the private sector to the public sector (aka “tax-and-spend”) doesn’t increase economic growth, it stifles it.

And he’s exaggerates when he suggests that “the growth of the entire economy” is contingent on whether government spending is cut by four-tenths of a percent of GDP this year.

THE PRESIDENT: Congress is already working towards a budget that would permanently replace the sequester. At the very least, we should give them the chance to come up with this budget instead of making indiscriminate cuts now that will cost us jobs and significantly slow down our recovery.

Are they? Maybe the Senate is. I’m not sure the House is looking to replace the sequester in their budget. Time will tell.

THE PRESIDENT: So let me just repeat: Our economy right now is headed in the right direction and it will stay that way as long as there aren’t any more self-inflicted wounds coming out of Washington. So let’s keep on chipping away at this problem together, as Democrats and Republicans, to give our workers and our businesses the support that they need to thrive in the weeks and months ahead.

Wouldn’t it be nice if he had said “let’s keep chipping away at this problem together, as Americans, …” rather than “as Democrats and Republicans”?

THE PRESIDENT: Thanks very much. And I know that you’re going to have a whole bunch of other questions. And that’s why I hired this guy, Jay Carney — (laughter) — to take those questions.

I have a question: Where is the President’s specific proposal? At 7:43 AM EST today POLITICO reported:

POLITICO: President Barack Obama will propose a package of short-term spending cuts and tax reforms in an effort to head off the looming sequester cuts Tuesday at 1:15 p.m., a White House official tells POLITICO.

What happened to the “package of short-term spending cuts and tax reforms?” It seems to have died between 7:43 AM and 1:15 PM when the President spoke.

(photo credit: White House photo by Pete Souza)

The President’s infrastructure investment argument

In his briefing yesterday White House Press Secretary Jay Carney said:

MR. CARNEY: [E]very proposal the President has put forward … has included significant investments in our economy — in infrastructure, in education, in putting teachers and police officers back on the street.

… they represent the President’s view that deficit reduction is not a goal unto itself; it should be in service of the broader goal, which is positive economic growth and job creation, and that we need to continue to invest wisely to ensure that our economy grows.

Investing in infrastructure, for example, doesn’t just create jobs in the near term; it helps build a foundation for sustained economic growth in the decades to come.

Mr. Carney and his boss use this argument often to justify many of the President’s proposed spending increases. The broader goal, they argue, “is positive economic growth and job creation … [to] build a foundation for sustained economic growth in decades to come.”

I expect Team Obama will be using this argument more frequently as the sequester and budget resolution debates heat up. They’ll probably use it again as a straw man to suggest that because Congressional Republicans oppose the Obama Administration’s proposed spending levels and particular spending plans, those same Republicans oppose all economic growth benefits that come from public infrastructure investment.

So let’s look at government capital investment in this context of long-term economic growth.

The Administration starts from a strong theoretical foundation. Capital investment, whether in the private or public sector, should lead to more productive workers, who will enjoy higher wages and improved living standards over time. When aimed at increasing productivity, capital investment (or capital formation) leads to “sustained economic growth in decades to come.” So far, so good.

But…

- Capital investment by government often pursues multiple policy goals, some of which conflict with maximizing productivity growth. If you’re investing for long-run growth you’ll invest differently than if you also have goals to maximize short-term job creation and to change the future balance of energy sources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (for instance). The pursuit of multiple policy goals lowers the expected economic growth benefit of public capital spending.

- Geographic politics distorts and often dominates government investment in physical infrastructure. Highway funds and airport funds especially are allocated in part based on which Members of Congress have maximum procedural leverage over the spending bill. Even if you could somehow get Congress to stop earmarking infrastructure spending (good luck), and even if you could rely on the Executive Branch not to allow their own political goals to influence how they allocate funds, local geographic politics would come into play at the state level, since much federal infrastructure spending flows through State governments. This is where reality most falls short of a valid theoretical starting point for increasing productivity and long-term growth.

- Non-geographic politics can distort government capital spending. This is principally an Executive Branch concern, as we saw with the Obama Administration’s decision to throw good money after bad to postpone Solyndra’s failure. And rent-seekers come out of the woodwork, looking to leverage their connections to government officials to win infrastructure investment contracts.

- Once “investment” is favored, everything gets relabeled as investment. The Obama Administration has been particularly guilty of this; almost every spending increase they propose is an “investment” of some sort. We should allow them some rhetorical leeway, and we should recognize that government has other reasons to spend money than just to maximize future economic growth. At the same time, it’s misleading when they claim that increased government spending that serves other policy goals (some quite legitimate) also increases future economic growth.

- There’s a difference between government investments in the commons and government spending that primarily benefits individuals. A new airport benefits all who use it. A scientific research grant benefits the researcher and society as a whole if his research advances our understanding. A subsidized student loan is an investment in human capital, but the return on that investment accrues mostly to the student and his or her family. That’s not wrong, it’s just having a more limited effect on increasing long-term growth for society as a whole.

- Government investment in physical infrastructure is slow. The Administration learned this as they tried to force money out the door in 2009 for “shovel-ready jobs” that turned out not to be there. This doesn’t mean you don’t build roads and improve ports and airports, it just means the short-term fiscal stimulus argument for this type of spending is weak.

- Government investment in physical infrastructure is intentionally expensive because of “prevailing wage” requirements, championed by construction labor unions, that mandate the government must pay more for workers than an aggressive private firm might be able to find in the labor market.

- We should evaluate the marginal productivity benefits of additional investment. The President sometimes argues that building the national highway system was good for growth, therefore his specific proposal to increase highway spending is good for growth, too. But those are different investments, and we need to examine the marginal benefits (and rate of return) on the specific incremental investments he is now proposing. The transcontinental railroad definitely increased national economic growth, but that doesn’t mean the feds should subsidize a costly California bullet train with questionable growth benefits.

- International comparisons of government infrastructure are silly. U.S. government capital spending should be determined based on what will most increase U.S. productivity without comparison to what other countries are doing. If American ports are clogged and that is harming our trade and slowing American economic growth, then we should upgrade our ports. We shouldn’t instead improve our airports because other countries have shinier ones. We have a different geography, a different economy, and different infrastructure needs than does China, or Japan, or Dubai or France. It is crazy to suggest that the U.S. should build bullet trains because China is doing so.

- Government investment faces no market discipline. Capital investment in a private firm can face some of the above challenges—a CEO, for instance, might want a new facility built in his hometown rather than where it will produce the highest rate of return. Or a firm might reject an investment that would maximize its’ workers’ productivity because that investment is inconsistent with the firm’s broader strategic goals. But these firms ultimately face the discipline of the market to curb their excesses. Government does not, and in some cases policymakers are rewarded by their election markets to distort infrastructure investment even farther from its growth-maximizing ideal.

- Government capital investment financed by raising taxes on private capital investment will slow long-term economic growth. While in theory there probably are government infrastructure investments with very high rates of return, all of the above reasons suggest that in practice the actual rate of return on government-directed investment is going to be lower than in the private sector. If you advocate raising capital taxes (on capital gains and dividends, for instance, as Senate Democrats appear poised to do) at the same time you argue for increased government capital spending, you’re shifting capital investment from the private sector to the public sector. That will slow long-run economic growth rather than increase it.

After all of these cautions you might conclude that I’m opposed to more highway spending or to all additional government capital investment. I’m not. America needs a robust, efficient, and plentiful supply of national physical and human capital. And there are definitely areas where smart government capital investment can increase productivity and contribute to faster long-run economic growth.

I am instead suggesting that the President’s infrastructure investment strategy is missing some key cautions, and that we shouldn’t use simplistic arguments and flawed logic, cloaked in attractive investment rhetoric, to justify enormous and often unrelated increases in government spending. We should recognize that in practice government infrastructure investment falls far short of its theoretic ideal, and we should therefore spend taxpayer money on it cautiously and wisely rather than with reckless abandon.

(photo credit: Robin Ellis)

Responding to Mr. Carney

I’d like to thank White House Press Secretary Jay Carney for giving me so much material to work with in his press briefing today.

MR. CARNEY: Well, there’s a lot in your question, so let me go first to the broader fact, which is that we have seen consistent job growth over almost three years.

Nope. Job growth began in March 2010 and was strong for March, April, and May. We then lost net jobs for four months. We have had continuous job growth since October 2010. That is two and a quarter years, which is not “almost three.” (Source: BLS)

If you start measuring in March 2010, job growth has averaged +141K/month. If you start measuring in October 2010, job growth has averaged +153K/month. If we were at full employment those numbers would be fine because you need around +125-150K/month to keep up with population growth. Given continued high unemployment those numbers fall far short of the job growth rate we need to return rapidly to full employment. We’re generally doing a bit better than treading water, but not much.

MR. CARNEY: But there’s more work to do and our economy is facing a major headwind, which goes to your point, and that’s Republicans in Congress.

This is an aggressive and, I think, novel presentation—labeling Congressional Republicans as an economic headwind. Those same Republicans should respond aggressively to this particular language.

MR. CARNEY: Talk about letting the sequester kick in as though that were an acceptable thing belies where Republicans were on this issue not that long ago, and it makes clear again that this is sort of political brinksmanship of the kind that results in one primary victim, and that’s American taxpayers, the American middle class.

You’re correct that the GDP number we saw today was driven in part by — in large part by a sharp decrease in defense spending, the sharpest drop since I think 1972. And at least some of that has to do with the uncertainty created by the prospect of sequester.

To the end of your question, I would say that the President has had and continues to have very detailed proposals, including spending cuts, that would completely do away with the sequester if enacted, that approaches deficit reduction — not just the $1.2 trillion called for by the sequester, but even beyond that — in a balanced way.

His logic is:

- The sharp decline in Q4 defense spending was in large part responsible for today’s bad (-0.1%) Q4 GDP growth number;

- The President wants to replace the sequester cuts with a “balanced” package of tax increases and other spending cuts;

- Republicans oppose the President’s reasonable “balanced” alternative;

- A recent shift suggests that Congressional Republicans appear to favor leaving the upcoming sequester in place;

- Therefore the bad Q4 GDP number is because Congressional Republicans refused the President’s reasonable alternative and may be willing now to leave the upcoming sequester in effect.

Problem #1 with this logic is that the President’s proposal would be deficit neutral, so any increase in discretionary spending that helped short-term economic growth would be mostly offset by cuts in other government spending and increases in taxes. If you buy the logic of yanking hard on the Keynesian short-term fiscal lever (big if) then your proposal needs to increase the deficit to get any first order GDP kick. So the tax-increasing solution Republicans are rejecting wouldn’t help GDP growth, it would just shift the components around so that government spending grew faster and private consumption and investment grew more slowly.

Problem #2 is that his sequence doesn’t work. Mr. Carney implies that last quarter’s GDP was harmed by Congressional Republicans’ movement in the past two weeks toward allowing the sequester to take effect. That puts the effect before the cause, which is hard to do.

MR. CARNEY: So it can’t be we’ll let sequester kick in because we insist that tax loopholes remain where they are for corporate jet owners, or subsidies provided to the oil and gas companies that have done so exceedingly well in recent years have to remain in place. That’s just — that’s not I think a position that will earn a lot of support with the American people.

The words “DEMAGOGUE ALERT” should flash any time you hear the ol’ corporate jet tax break. Eliminating it would raise a few billion dollars of revenue compared to spending problems measured in trillions.

Still, Republicans should find a way to propose repealing this tax break and using the revenue to lower some other tax in a way that both parties like. Neutralize the stupid talking point by getting rid of this tax preference, but don’t use the revenue raised to increase government spending. Don’t wait for tax reform, get rid of this one quickly in the right way.

MR. CARNEY: Speaker of the House Boehner put forward, in theory, at least, a proposal late last year that said he could find $800 billion in revenues through tax reform alone — closing of loopholes and capping of deductions. So surely what was a good idea then can’t suddenly be a bad idea now.

Did he forget about the $617 B of tax increases that were just enacted? No. This is another important rhetorical trick – suggesting that the previously offered +$800B and the recently enacted +$617B are additive rather than duplicative. I’m certain that’s not how Congressional Republicans think of it. Watch for this rhetorical trick to be repeated often.

MR. CARNEY: The President put forward a proposal to the super committee that reflected the balance that was inherent in every serious bipartisan proposal, including the Simpson-Bowles proposal. A refusal at the time to allow revenue to be a part of that meant that the super committee did not produce.

Congressional Republicans told me at the time that the Administration was nowhere to be found during the Super Committee’s failed attempts in the fall of 2011. “Completely disengaged – absent,” was how one insider described the Administration.

Republicans on the Super Committee offered to their Democratic colleagues to accept higher revenue in exchange for either significant entitlement reforms or pro-growth tax reform. Mr. Carney’s claim that Republicans “refus

There’s more, but that’s enough for today.

(photo credit: Talk Radio News Service)

More on tax reform: Schumer v. Baucus

Based on some further development and feedback I’m going to update last week’s post on how Senate Democratic plans for the budget resolution interact with the prospects for enacting significant tax reform. My core projection is still quite pessimistic, but I think I have a better feel for the legislative dynamics.

Update: During debate on H.R. 8, the New Year’s tax increase law, House Chairman Camp made clear that he will move through the House a bill that is revenue-neutral (after H.R. 8 took effect). This makes a “preconferenced” Baucus-Camp-Hatch bill highly unlikely, and means that any agreement would come only in a conference after the House had passed a revenue-neutral bill. Such a conference report might or might not be revenue-neutral, but at least the first stage of the process would not increase revenues.

Sen. Schumer’s Senate reconciliation for “tax reform” won’t happen.

A couple of friends pointed out that a Senate reconciliation bill can only be produced by the House and Senate passing identical versions of a budget resolution in the form of a conference report. This means that Senator Schumer’s push last week for a 51-vote procedural path to enacting a tax bill can happen only if the Senate Democratic majority reaches an agreement on deficits, debt, and aggregate spending and tax levels with a Republican majority House. This leads me to four obvious conclusions that I missed in last week’s post:

- Senate Democrats can’t force the Senate to pass a partisan tax bill through reconciliation without House Republican acquiescence on creating the process to do so.

- Even in the unlikely scenario where House Republicans and Senate Democrats agreed to create such a reconciliation “vehicle” for tax reform, they couldn’t do so unless they also agreed on the other components of a budget resolution: deficit and debt levels, spending and tax aggregates, and the aggregate size of changes to major entitlement programs and discretionary spending.

- Therefore, Senator Schumer’s prediction early last week of a 51-vote reconciliation path for Senate passage of “tax reform” has almost no chance of happening.

- And if tax reform is even to pass the Senate it will need bipartisan support. For Chairman Baucus this means he needs Finance Committee Ranking Member Hatch early in the process, and House Ways & Means Committee Chairman Camp after/if the Senate passes a bill.

In support of this, I’d note that in a press conference last Wednesday Senator Schumer did not push the reconciliation idea, instead describing it as something that Chairmen Murray and Baucus would work out. I’ll bet that idea is now dead.

Baucus v. Schumer

I think Sen. Schumer

Tax reform has traditionally meant broadening the tax base and lowering rates and reducing economic distortions by creating more horizontal equity in which taxpayers in similar situations are treated the same by the tax code. In the Schumer[/Murray/Reid/Obama?] view a new tax bill would introduce as many new tax preferences as it eliminates, it would favor certain industries and firms over others, and it would finance more government spending. That is not tax reform, that’s liberal tax policy labeled as tax reform.

I think Chairman Baucus wants to do bipartisan tax reform while the President and Senator Schumer want to raise taxes on certain individuals and businesses. Those are fundamentally different goals. Chairman Baucus’ path is, in theory, something that could be worked out with his Republican House counterpart Chairman Camp. The Obama/Schumer path leads to partisan stalemate once again.

I also think Chairman Baucus recognizes that Republicans will not agree to large net tax increases. Whatever his own fiscal policy preferences, I think Mr. Baucus knows that a Senate budget resolution that requires a tax bill to raise “too much” revenue will make enactment of a bipartisan tax reform bill much more difficult.

At the same time, I think Chairman Camp may feel a similar degree of flexibility on aggregate revenues. In mid-2011 and even as late as December, the Boehner-led House Republicans were willing to agree to higher total revenues if accomplished through a tax reform bill they liked. Now the policy and political wounds of the recent tax increase law are still fresh, and so while Chairman Camp might still be willing to compromise and agree to higher total taxes, most of his House and Senate Republican colleagues would now reject them, even if they were part of tax reform. I think Mr. Camp would be more optimistic than I am about the additional revenues that could be generated from a pro-growth tax reform (I assume a pessimistic +$100-$150B over 10 years), and he might think that reformed tax code and stronger IRS enforcement could raise revenues without constituting “tax increases” in a traditional sense. Nevertheless, I think he’d have a difficult time rallying Republican support for any tax reform bill that contained a net revenue increase. With the last fight and the new law the President has used up any prior Republican flexibility on total tax levels.

It appears that Chairmen Camp and Baucus are trying to find both an aggregate revenue level and a set of tax reforms where they (and Finance Committee Ranking Member Hatch) can agree. At the same time, their respective caucuses will continue to argue and fight over whether or not total taxes can go up. On the Senate side Budget Chairman Patty Murray and Democratic thought-leader Senator Schumer are staking out the left flank for a likely budget resolution and tax reform stalemate. House Republicans and Senate Democrats are unlikely to pass a common budget resolution, to agree to a common aggregate revenue level for a tax bill, or to create a fast-track legislative process to enact such a bill. Messrs. Camp, Baucus, and Hatch will have to see whether they can substantively agree and build a bipartisan legislative coalition in support of true tax reform after a bruising set of partisan fights on the sequester, continuing resolution, and budget resolution. That will be very hard to do, and it’s why I’m still pessimistic about the prospects for real tax reform.

What to watch

- Watch Chairman Baucus, who was notably absent from the Reid/Durbin/Schumer/Murray budget press conference last week. Do you see signs that he is arguing (behind Democratic closed doors) for a budget resolution that allows him to pursue bipartisan tax reform? Do you see signs of a Schumer vs. Baucus argument on total tax levels?

- Watch in-cycle Senate Democrats during the budget resolution process. Are they onboard with the Schumer strategy? Are they OK voting for a budget resolution that raises taxes a lot, given that it’s unlikely to be worked out with the House in a final version?

- Watch the President, Press Secretary Jay Carney, and Mr. Lew if he’s confirmed. If they support the Murray/Schumer argument instead of the Baucus view, then they are not looking to enact tax reform, but instead to position themselves for what they anticipate will be a[nother] aggressive policy debate that will likely result in a legislative stalemate.

- Watch for any signs of Camp-Baucus-Hatch cooperation as they try to forge an alliance while being pulled apart by their respective caucuses.

(photo credit: ajagendorf25)