Another unforced error?

I didn’t think it was possible for Team Obama to make their problems with the individual insurance market any worse.

I was wrong.

In an interview with Chuck Todd yesterday, President Obama spoke about the 8-10 million Americans whose insurance policies are being canceled:

THE PRESIDENT: So — the majority of folks will end up being better off, of course, because the website’s not workin’ right. They don’t necessarily know it right. But it — even though it’s a small percentage of folks who may be disadvantaged, you know, it means a lot to them. And it’s scary to them. And I am sorry that they — you know, are finding themselves in this situation, based on assurances they got from me. We’ve got to work hard to make sure that — they know — we hear ’em and that we’re gonna do everything we can — to deal with folks who find themselves — in a tough position as a consequence of this.

… But obviously, we didn’t do a good enough job in terms of how we crafted the law. And, you know, that’s somethin’ that I regret. That’s somethin’ that we’re gonna do everything we can to get fixed. In the meantime —

MR. TODD: By the way, that sounds like you’re supportive of this legislation.

THE PRESIDENT: Well, you — you know — Various things that are out there.

We’re — we’re looking at — a range of options.

On Air Force One today, Deputy Press Secretary Josh Earnest followed up by answering a reporter’s question:

Q Josh, the President last night mentioned, when he apologized for problems with the cancellations of policies, that he was going to instruct his administration to go back with some sort of a loop. Can you flesh that out? What are you guys looking at in terms of canceled policies?

MR. EARNEST: I’m not in a position to add a whole lot of additional detail to what the President said last night. The President did acknowledge that there are some gaps in the law that need to be repaired. He has directed his team to consider some administrative solutions to those problems, some steps that his administration could take unilaterally that would address some of those gaps.

Sounds good, right? There’s a problem, that “a small percentage of folks” (8-10 million people) are facing canceled individual market health insurance plans, and some of them are “disadvantaged” by the new options, or will be once they can see them on a functioning healthcare.gov. The President has directed his team to consider some administrative solutions to fix the problem, to “address some of those gaps.”

The problem with the President’s public statement is that he has now frozen the individual insurance market in place until he announces his new solutions. If you are one of the 8-10 million Americans with a canceled insurance policy, President Obama just created an enormous incentive for you to hold off on buying a new policy, to wait for the Administration to offer you a new solution.

Had they announced a new solution today, they would not have created this problem. The disincentive to buy a new plan comes from offering hope of a better outcome with no specificity or timeframe.

This new disincentive to buy insurance applies nationwide and is independent of the broken federal exchange website. I expect states running their own exchanges like California and Colorado, Minnesota and Maryland, DC, New York, and Connecticut, will see their new enrollments now drop as those with canceled policies wait for the President’s next move. States participating in the federal exchange won’t see any drop because the broken website is already preventing signups. Still, even in those states the President has created a new reason not to buy insurance on the exchange when it eventually does work, at least until he announces his new policy.

Because the story is so hot, and because the President’s allies in Congress are desperate to offer their angry constituents some hope, we can be assured that the President’s ambiguous offer of future hope, and the purchasing disincentive it creates, will get a lot of attention.

The optimistic interpretation for this new policy signal is that President Obama and his team understood this balance when the President spoke yesterday, that they weighed the cost of further discouraging new signups against the benefit of partially relieving growing pressure to help angry citizens who liked their canceled policies.

The pessimistic interpretation is that this is yet another unforced error, another self-inflicted wound.

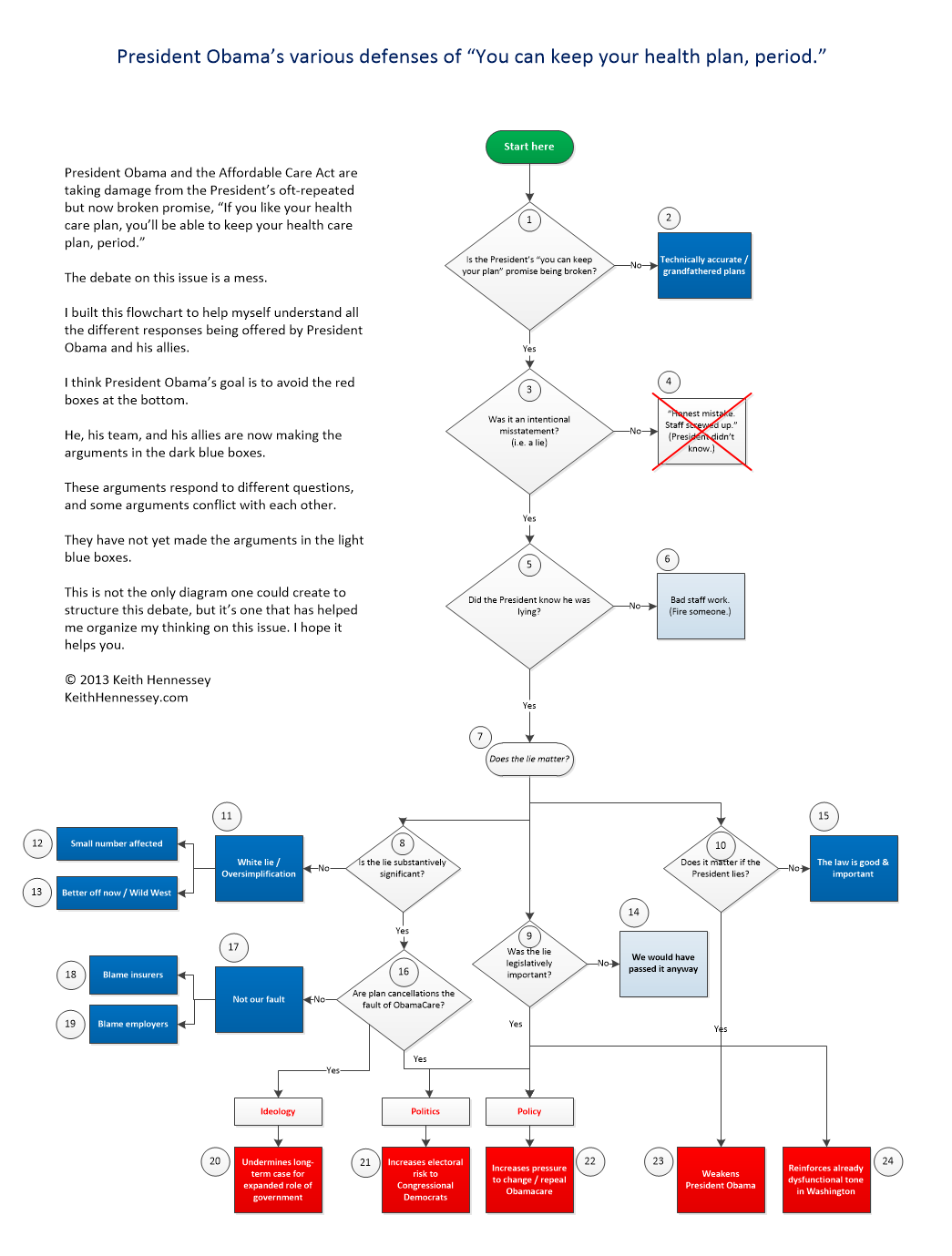

Ensuring presidential accuracy & honesty

Three recent articles and columns prompted me to write about President Obama’s oft-repeated false promise, “If you like your health care plan, you can keep your health care plan, period.”

One was my former White House colleague Marc Thiessen’s column, “A Dishonest Presidency.” The second was Ron Fournier’s column: “Lying About Lies: Why Credibility Matters to Obama.” The third was this Wall Street Journal article last Saturday.

In that third article this sentence grabbed my attention:

One former senior administration official said that as the law was being crafted by the White House and lawmakers, some White House policy advisers objected to the breadth of Mr. Obama’s “keep your plan” promise. They were overruled by political aides, the former official said.

Overruled by political aides? On a question of accuracy and honesty?!?

I won’t belabor the substance of the “keep your plan” promise. It is unequivocally and incontrovertibly inaccurate. Glenn Kessler does a good job of walking through it. I instead want to focus on the process point from the WSJ story and compare it to my experience.

In more than six years on the staff of President George W. Bush’s National Economic Council, I had the type of conversation described in the WSJ article hundreds of times. As a policy aide one of my core responsibilities was to make sure the President’s policy was accurately communicated and that we could back up every word in the President’s prepared remarks. This was mission critical for us policy aides–I knew that if President Bush said something incorrect on which I had signed off, I was at serious risk of being fired, even if it was just an honest mistake.

My debate with Jared Bernstein

At the New York Times’ Room for Debate site, former VP Biden Chief Economist Jared Bernstein and I debate the next steps in the fiscal struggle.

Writing a Budget to Prevent Another Shutdown

Dr. Bernstein now works as a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The fiscal Gordian knot

Here is the fiscal Gordian knot:

Congressional Republicans will only agree to sequester relief if offset by mandatory spending cuts, but President Obama and Congressional Democrats will only agree to mandatory spending cuts if taxes are also increased, and Republicans won’t raise taxes.

This fiscal Gordian knot caused the Super Committee to break down in late 2011. There was no agreement to replace the automatic discretionary spending cuts (aka the sequester) that President Obama proposed and signed into law in the Budget Control Act of 2011. He made a fundamental miscalculation when negotiating that law: he mistakenly assumed that Republican defense hawks would squawk so loudly at the disproportionate defense cuts imposed by the sequester that some Republicans would be willing to support tax increases in exchange for higher defense and non-defense discretionary spending.

The sequester replacement negotiations earlier this year were a second attempt by the President to untie the knot. That time he used political force, trying to bludgeon Republicans into agreeing to tax increases. Again he failed.

As the Republican demand to defund ObamaCare dissolved last week, the President and Leader Reid once again erred. Unsatisfied with a straight extension of current law spending and the debt limit and a political victory over Republicans, they increased their demands. They shifted from a sure-win defensive posture to an aggressive but risky offensive posture, demanding higher spending offset in part by tax increases.

House Budget Committee Chairman Ryan floated a sound and predictable Republican alternative: substituting mandatory spending cuts (specifically, changes to entitlement programs proposed by the President in his budget) to offset higher discretionary spending for defense and (I think) non-defense. This formed the core of Speaker Boehner’s recent offer to the President. The President rejected this offer because House Republicans were unwilling to also raise taxes. For a third time the President failed to untie the fiscal Gordian knot.

The negotiation now lies with Senate Leaders Reid and McConnell. (VP Biden, the only member of the President’s team with a proven track record of closing deals with Republicans, has apparently been locked away at Leader Reid’s insistence.) While the form of the Reid-McConnell negotiation is about the timing for when short-term extensions of the continuing resolution and the debt limit would next expire, the underlying substance of the negotiation is this fiscal Gordian knot. Both leaders are trying to structure both this negotiation and the next to maximize their leverage to achieve their respective fiscal goals.

Democrats had the advantage last week when they were playing defense, trying to block Republican demands to defund or delay parts of ObamaCare. The combination of the Cruz-Lee vaporware defund strategy, a House Republican conference unable to agree on anything, a Republican party message that was muddled at best, and an effective use of the bully pulpit by the President led to plummeting poll numbers for Congressional Republicans. Many Senate and some House Republicans seemed anxious to negotiate a deal that would temporarily both end the government shutdown and extend the debt limit deadline. With Leader McConnell’s tacit approval, Senator Collins kicked off the compromise attempt by initiating a rump group negotiation with a few Democrats. Leader Reid killed this fledgling bipartisan negotiation and once again took matters into his own hands, leading to the current discussion with his Republican counterpart.

Republicans now have a slight medium-term advantage for three reasons. I suspect that Democratic appropriators don’t feel as strongly about wanting to raise taxes as Congressional Republicans feel about not wanting to raise taxes. When they are eventually forced to choose, I’ll bet that enough Democrats (specifically, the appropriators) will accept entitlement spending cuts to fully offset higher discretionary spending, without any tax increases.

In addition, current law defaults to a position Republicans are more willing to accept than Democrats. Senators Cruz and Lee learned that he who favors current law has a significant tactical advantage in a shutdown fight. President Obama’s sequester in current law means the same is true on spending, but this time it favors fiscal conservatives.

Finally, when the public debate was “government shutdown vs. defunding ObamaCare,” Democrats had a communications advantage. Now the debate is shifting to “whether to bust the 2011 bipartisan budget deal by increasing spending and taxes.” That is right in the wheelhouse of today’s Republican party.

By insisting on tax increases to offset higher discretionary spending, Leader Reid and President Obama are doing what neither Boehner nor McConnell has been able to do for several weeks: unite Congressional Republicans. And Republicans have a strong counter: we will agree to higher discretionary spending as long as it’s offset only by entitlement spending cuts proposed by the President. I appreciate that many Democrats think it’s outrageous not to also raise taxes (and they’re nuts for thinking that), but that’s not the point. The key is that while most House and Senate Republicans felt forced into a shutdown over “defunding ObamaCare,” I’d bet that most of them will reject any Reid proposal to unravel the only bipartisan fiscal success of the past five years or to increase spending funded by higher taxes, even if such a rejection means that the government shutdown continues.

If Leader Reid and the President continue to insist on more spending and higher taxes, and especially if they want to try to enact it now, I think it backfires on them. They will reunite Congressional Republicans and give Republicans a much stronger rhetorical perch than they have had so far. Unfortunately, they would also continue the current stalemate.

(photo credit: Jay Allen)

An introduction to the debt limit

This post offers a plain vanilla explanation of the debt limit. This is basic background aimed at fiscal policy novices. I oversimplify in a few places for ease of understanding and push some caveats and complexities down to footnotes. Some of my past readers may find this too elementary, but it’s a foundation I can build upon in future posts that will offer more detail and discuss the current stalemate.

The federal government’s fiscal year begins October 1, so federal fiscal year (FY) 2013 just ended and FY 2014 just began last week. In FY 2013 the federal government collected about $2.813 trillion in revenues and spent about $3.455 trillion. The difference between those two numbers, $642 billion, is the unified budget deficit for Fiscal Year 2013. We say unified budget deficit because we’re looking at all money flowing into the federal government (revenues) and all money flowing out (spending), and not distinguishing among different sources or uses of those funds. In other contexts, usually having to do with Social Security, we might want to treat on-budget and off-budget spending and taxes differently, but for this discussion we will use unified numbers.

I think of these enormous numbers as representing flows of cash. (Please see the footnotes below for two caveats: [1] [2]) The key question: if last fiscal year the government spent $3.455 trillion in cash but collected “only” $2.813 trillion in cash, where did it get the other $642 billion in cash it needed to pay the rest of its bills?

The federal government borrowed it. The Treasury department sold IOUs that we call Treasury bonds (technically bills, notes, and bonds, depending on the timeframe). Investors paid cash for these IOUs, and in exchange they got a promise that Treasury will pay them back later, in full, with interest, and on time. We say that Treasury issued debt to raise cash. Treasury’s issuance of debt is a means to an end: it is the mechanism Treasury uses to get the cash it needs to pay all the government’s bills (which we call government obligations) on time.

The President’s irrelevant debt limit threat

Late last week President Obama called Speaker Boehner to say that he wouldn’t negotiate on the debt limit.

This strikes me as an irrelevant threat. As best I can tell, no one was proposing such negotiations. Indeed after the tax increase fight last December, Speaker Boehner made a point that he would henceforth return to regular order rather than engage in ad hoc one-on-one negotiations with the President.

To increase the debt limit one needs the House and Senate to pass identical bills which raise (or suspend for a time) that limit, and then for the President to sign that bill, or at least not veto it. To pass identical bills it may be necessary for Speaker Boehner and Leader Reid to negotiate. But the President and his advisors don’t have to be part of that discussion. Speaker Boehner needs only the President’s reluctant after-the-fact acquiescence to a House-Senate agreement legislated without the President’s direct participation. To succeed Speaker Boehner does not need President Obama’s up-front and public approval.

Had the President wanted to make a threat that mattered, he would have told the Speaker “If you send me anything other than a clean debt limit bill, I’ll veto it.” That would have been a red line. He didn’t make such a threat, and that’s intentional. But the actual threat made by the President sounds tough to his allies without actually constraining his future options. The President won’t have to retreat (again) from a red line threat, because he hasn’t actually drawn a red line.

The legislative reality is that in the current House-Senate configuration, President Obama will never veto a debt limit bill.

He won’t have to. If there’s a provision that he hates enough that he would veto it if it were attached to a debt limit bill, he can simply threaten a veto, publicly and/or privately. He can tell Leader Reid, “Harry, don’t send me that bill or I’ll have to veto it.” And, if the threat is unequivocal enough, Leader Reid will then ensure that a bill containing that provision does not pass the Senate.

Alternatively, the President can use his bully pulpit to urge his allies in Congress to block any bill that contains the offending provision. The bully pulpit and the hammer of a veto threat (rather than a veto) are sufficient tools for President Obama to prevent big policy changes that he detests being attached to a debt limit extension.

The simplest example would be if the House were to pass a debt limit extension that also “defunds” ObamaCare. While President Obama could threaten a veto of such a bill, and he might, it’s likely an unnecessary threat. Acting on their own, Senate Democrats and Leader Reid would never allow such a provision to pass the Senate, thus obviating the need for a Presidential veto. In this case the veto threat matters only if it’s needed to shore up Democratic votes.

Now let’s return to the actual threat made by the President. It’s easy to imagine Speaker Boehner turning to his staff and saying, “The President just cut himself out of our debt limit negotiations with the Senate. Let’s see what we can work out with them. If the White House doesn’t like something we want attached, they can try to convince Harry to block it. We can’t big stuff like defunding or even Keystone on this bill, but there may be a small win or two that Harry would accept despite carping by the White House.”

Now it may happen that Leader Reid, either on his own or at the behest of the President, refuses to allow the Senate to consider anything other than a clean debt limit bill. The President might still get his desired result, if Leader Reid is on exactly the same page and if the Senate position prevails in the upcoming back-and-forth with the House.

But by saying “I won’t negotiate,” the President has moved himself into the background, into a position of indirect influence through his allies on the Hill. This is most likely to matter on important but second-tier issues, things which the President opposes but which Senate Democrats may be willing to accept, or may find they have no alternative but to accept because no other legislative path to enacting a debt limit increase is possible.

The key for Congressional Republicans is then to exploit whatever procedural leverage they can generate, combined with policy differences (or differences in intensity) between the President and Congressional Democrats. House Republicans can attach a modest policy change to a debt limit bill and maybe get enough Senate Democrats to swallow it. If they do, the President will have to accept it, because he can’t risk vetoing a debt limit extension over the inclusion of a second-tier policy he doesn’t like.

House & Senate Republicans did this last spring. They attached a “no budget no pay” provision to a debt limit extension. Senate Democrats accepted it, and the President signed the bill after insisting on a clean bill. As a result of this provision, the Senate passed a budget resolution for the first time in years. This was a modest policy and process win, but a win nevertheless.

The President says he refuses to negotiate on this bill. That should suit Congressional Republicans just fine. They can and should instead try to work something out with their colleagues on the other side of the aisle. The President’s ineffective threat may provide an opportunity to get a small policy win or two as an attachment to a debt limit extension.

Another op-ed

Here’s another op-ed from Ed Lazear and me. This one is running on Fox News’ site.

Bush ended financial crisis before Obama took office — three important truths about 2008

POLITICO op-ed

Ed Lazear and I have an op-ed on POLITICO based on our recent paper.

Here’s the op-ed: Who really fixed the financial crisis?

And here again is the paper: Observations on the Financial Crisis.

As with most publications, we didn’t choose the title of the op-ed, although in this case it worked out fine.