The Administration’s flawed health care argument threatens their fiscal policy strategy

The President’s fiscal policy is based upon a flawed health care premise, and the flaws are becoming apparent to a wider audience. The Administration’s fiscal strategy is to increase short-term spending (and not just on health care) and more than offset those spending increases through long-term reductions in federal health care spending. In theory this strategy could work, but by ducking painful policy choices on health care reform that would actually reduce long-term health care spending, the President and his team have placed their health care and fiscal policy strategies in jeopardy.

Flaw 1: The arithmetic is nearly impossible. These bills start by increasing federal health spending 10-15% by creating a new entitlement. That digs a huge hole before beginning to address the existing fiscal problem.

Flaw 2: As it becomes increasingly more difficult to pass health care reform legislation, the Administration is lowering the bar to say such legislation must not increase the long-term deficit (rather than must reduce it). But to make their fiscal policy case, the Administration needs to be able to demonstrate that health care reform will reduce long-term deficits.

Flaw 3: The Administration has not recommended policies that would actually reduce long-term federal health spending. When experts (like CBO) point this out, the Administration misrepresents the analysis and repeats their claims of long-term savings. As CBO has dismantled this argument, it has placed health care legislation in jeopardy. In addition, the lynchpin of the President’s fiscal policy case is buckling.

Flaw 4: The Administration says the long-term savings will exist, but the savings are too nebulous to be precisely scored. What, then, do they plan to display in next year’s President’s budget if they are successful? At some point someone would have to attribute specific long-term budgetary effects to an enacted health care reform bill. You can’t just hand-wave past this problem forever. It will catch up to you.

Challenge 1: I challenge the Administration to publish their own estimate of long-term budgetary savings from any of their long-term proposals. (They can’t because their professional estimators agree with CBO.) Let’s watch how NEC Director Dr. Larry Summers struggled with these flaws yesterday on NBC’s Meet the Press with host David Gregory.

SUMMERS: That’s why the president has made health care a central issue in long-term deficit reduction. It’s going to be the largest part of the federal, the federal budget. So we’re going right at the deficit, but we’re going at the issue that’s measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars, federal dollars, which is federal health care spending. And that’s the big fight the President’s committed to. GREGORY: The difficulty of deadlines being missed and more public opposition to health care leads to the question of whether or not the president is losing the economic argument, that is the argument that health care is essential as an economic fix. SUMMERS: It is essential as an economic fix. It’s essential because of how much of the federal budget health care represents. It’s essential because it’s so important for the competitiveness of American businesses. You know, for some of the automobile companies, the health insurance companies are actually their largest supplier. And it’s essential to slow the growth of health costs if American families are going to see rising wages that rise ahead of inflation. So it is essential.

Flaw 5: CBO says the House bill would increase the budget deficit over the next ten years. They’re $239 B short.

Flaw 6: CBO says the House bill will result in bigger and ever-increasing deficits in the long run. This is because the bill starts with a huge spending increase, and then offsets fast-growing health spending increases with slow-growing tax increases

Flaw 7: While health cost growth is a huge and growing federal budget problem today, it’s actually not the largest source of growth for the next 15-20 years. Demographics and aging of the population is. To address this one needs to change the demographic parameters of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. By ignoring demographics, the Administration can punt on Social Security reform (which Speaker Pelosi definitely does not want to do.) But even if health reform legislation achieved the President’s stated goals, the benefits would build very slowly over time. We would still have to address the medium-term demographic cost driver.

Flaw 8: Dr. Summers is right that we need to slow health cost growth if American families are going to see rising wages that rise ahead of inflation. That is why rising health costs do not harm the competitiveness of American businesses. They hurt the workers at those businesses. In addition, the health insurance mandates now trumpeted by the President and Speaker would raise premiums costs for most Americans. Let’s return to Mr. Gregory and Dr. Summers:

GREGORY: That’s a very important point, and yet the CBO, the Congressional Budget Office, has looked at this, a nonpartisan actor in this debate, and has said there is a shortfall in paying for it even over the first decade, and that shortfall grows in subsequent decades. As you look at these health care plans, do there have to be fundamental changes if you’re going to avoid adding to the deficit down the line? SUMMERS: CBO said that about one of the bills that’s passed, one of the committees. This is why the discussions are continuing. No bill is going to move forward that is not over the first 10 years scored by the CBO as budget neutral. But the President’s — in addition to insisting on budget neutrality, which we didn’t use to do, the President’s doing another important thing. It’s what we’ve called a belt-and-suspenders approach. There’s some things — how we pay drug companies, for example — where you can do the accounting very accurately and you can see what happens to the deficit. There are other things, encouraging — encouraging preventive care, taking the whole reimbursement system out of politics — where it’s much more difficult to do the exact calculation. And so the CBO doesn’t give us any credit for them even though most people would say that, over time, they’re likely to have some benefit. And so we’re doing both sets of things. And so I think we’ve got a lot of basis for being optimistic that, whatever the CBO says, it’s going to end up better. But we’re being very conservative. That’s why it’s belt-and-suspenders. We’re not taking any account of that second set of changes, the preventive care and all of that. This is the most fiscally responsible approach to introducing a major structural change in the economy that’s ever been pursued. If you look at what happened with Medicare; if you look at what happened with prescription drugs; if you look at what happened when food stamps was introduced, there has never been this degree of careful scrutiny of long-run — long-run cost impacts. And it’s right because the center of this has to be containing health care costs, otherwise it’s not going to work for most families.

Flaw 9: CBO did not say that it’s difficult to calculate how much the President’s “IMAC” Medicare commission would save. CBO said, “enacting the proposal, as drafted, would yield savings of $2 billion over the 2010-2019 period — in CBO’s judgment, the probability is high that no savings would be realized –Looking beyond the 10-year budget window, CBO expects that this proposal would generate larger but still modest savings on the same probabilistic basis.”

Challenge 2: I challenge the Administration to produce three experts who would say that the specific IMAC legislative language offered by the Administration would produce significant long-term budget savings.

Flaw 10: While the Administration asserts that providing more information by itself would significantly slow the growth of health spending, most (all?) health experts say you also have to change incentives. Here’s CBO:

Other approaches — such as the wider adoption of health information technology or greater use of preventive medical care — could improve people’s health but would probably generate either modest reductions in the overall costs of health care or increases in such spending within a 10-year budgetary time frame. Significantly reducing the level or slowing the growth of health care spending would require substantial changes in those incentives.

The Administration’s health care reform and fiscal policy strategies are based on flawed premises. When neutral and non-partisan referees like CBO point out these flaws, both strategies collapse. The damage to the President’s health care reform effort is evident. I think the damage to his fiscal policy strategy will soon become apparent as well.

(photo credit: Collapsed by Martin Cathrae)

Understanding second quarter GDP

This morning the Commerce Department released their initial round of data for second quarter (Q2) GDP. Real GDP shrank at a 1.0 percent annual rate in the second quarter of this year. As a reminder, this does not mean GDP shrank 1 percent in the second quarter. It means that it shrank at a rate that, if extended through a whole year, would cause the economy to shrink 1% over the course of that full year.

When the economy is performing well it grows a little faster than 3% per year. Coming out of a deep recession you would hope for even faster growth, since your starting point is so low.

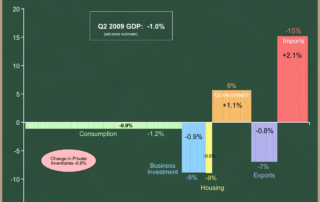

First let’s look at how things have changed over time. We can learn a lot from a simple picture. As always, you can click on any graph to see a bigger version.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the body that officially defines when recessions begin and end. Technically, they pick points that represent “peaks” and “troughs,” and then the recession is the time between a peak and a trough. NBER said that the peak was in the fourth quarter of 2007, so we say that’s when the recession began.

What jumps out at me from this graph is the difference between two parts of the recession. The graph bumps around between Q4 2007 and Q3 2008, then falls off a cliff. The press commentary (including from “sophisticated” analysts) talks about the recession that has lasted since the fourth quarter of 2007. While technically correct, that loses a tremendous amount of information. The severe recession, the one that has caused so much pain, really began in September 2008 when the financial crisis hit hardest. The current recession has been a mild recession for three quarters, interrupted by a severe financial shock which triggered three quarters (so far) of severe recession. Let’s hope today’s news means we are through the severe part and into a third phase.

It’s important to remember that the numbers you hear reported are growth rates. We learned today that U.S. GDP shrank 6.4% in the first quarter of this year, and another 1.0% in the second quarter. You can see how the line slopes downwardly sharply ending in the “09 Q1” point – that downward slope is the 6.4%. The economy shrank in the second quarter, so the line is still going down. But it didn’t shrink as much, so the line isn’t sloped downwardly as sharply as over the past few quarters. That gentler downward slope is today’s -1.0%.

The business news channels are treating today’s -1.0% number as fairly good news, for two reasons. The recession is slowing down – we’re still going down, but not as rapidly. Everyone hopes that this signals that a “bottom” (on the graph) is coming soon, and that things will soon turn positive. In addition, the -1.0% is a little less worse than markets expected. The consensus market expectation was for -1.5%, so in this case the bad news is a little less worse than expected, and financial markets treat that as a good thing.

This fits with the President’s new language on the economy, used for the first time a few days ago. They have (finally) found their new tone on the economy, and I think they hit a sweet spot from a communications perspective:

So, we may be seeing the beginning of the end of the recession. But that’s little comfort if you’re one of the folks who have lost their job, and haven’t found another.

The first sentence is optimistic but cautious. The second sentence is compassionate. They have found language that allows the President to sound optimistic and look good if things gradually improve over the next few months, but that doesn’t get him in too much trouble if things go south, and doesn’t make him look out of touch with the painful employment picture. It’s not risk-free: if the jobs market data continues to get worse, he risks having looked too optimistic. This is one of the harder balancing acts for the President and his advisors.

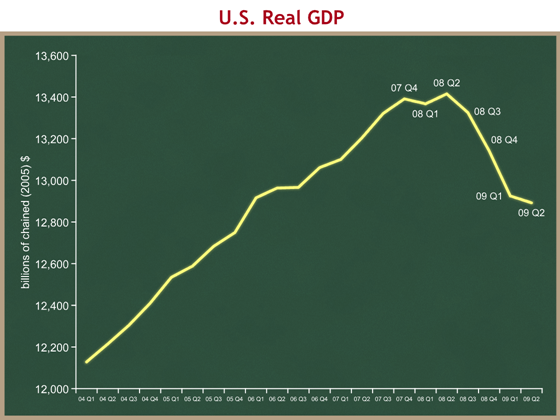

Let’s return to the numbers. For comparison we’ll begin by reviewing what happened in the first quarter of 2009. I have updated this graph to reflect today’s revisions to Q1 09 data.

We can see that in the first quarter:

- The economy shrank at a 6.4% annual rate. This is revised downward from the previous estimate of -5.5%.

- Consumption, which accounts for about 70% of the economy, was just above flat. It grew at a 0.6% rate, contributing 0.4 percentage points of growth.

- Business investment and housing tanked, shrinking at a 39% rate. Combined they account for a -6.6% decline in the overall GDP growth rate.

- Exports shrank, shrinking GDP, but imports shrank as well. Because imports subtract from GDP, the combination of the two was a net positive for overall growth.

- Firms weren’t building up inventories, and that sucked out a lot. Government was a slight drag.

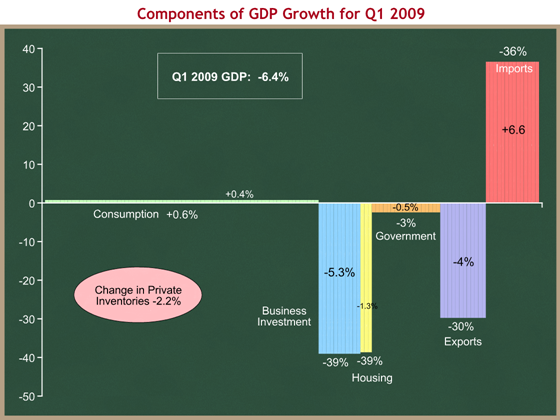

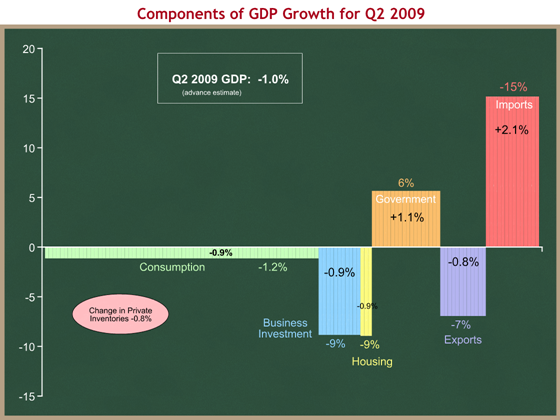

Now let’s look at what happened in the second quarter of this year. I think it’s most useful to compare the Q1 and Q2 graphs. You don’t even really have to look at the numbers – just the colors and heights of the columns should tell you a lot.

We can see that in the second quarter:

- The economy shrank at a 1% annual rate.

- Consumption shrank at a 0.9% annual rate, subtracting 1.2 percentage points of growth. UH-OH.

- The huge change is in investment, both in businesses and housing. They’re still shrinking, but at a 9% annual rate, rather than the 39% annual rate from Q1. These two components knocked off 6.6 percentage points in Q1, and now they’re knocking off 1.8. That’s the biggest reason for the change, and it’s the big good news in this report.

- The same is true for exports and imports. Exports shrank at a 7% rate in Q2 compared with 30% in Q1. Exports are still declining, but not as rapidly as they were.

- Government spending is now contributing to GDP growth. There’s a fairly big swing from Q1 to Q2.

- Inventories are being drawn down, but not as fast as they were in Q1.

The big change in government spending surprised me. Is the stimulus actually working that fast? It turns out that 60% of the growth from Q1 to Q2 is defense spending, so no. 25% is increased investment by State & local governments. It’s possible that some of that latter amount is higher because of anticipated stimulus funds from the feds, but I’d be surprised if much of it was.

Were it not for that -0.9% in consumption, this would be an across-the-board improvement from Q1. On CNBC this morning CEA Chair Dr. Christina Romer was asked about the decline in consumption, and she said there isn’t a huge difference between a +0.6% in Q1 and a -0.9% in Q2. I hope she’s right, but fear she may not be. That change may be statistical noise, but remember that our labor market is still incredibly weak. If people don’t have jobs, they aren’t getting paychecks, and they won’t spend much. We have to watch the labor market, not just the stock market.

Things to look for:

- Jobs Day is a week from today, when we’ll see what happened to the labor market in July.

- Sometime in August the Administration will release a revised economic forecast as part of the Mid-Session Review of the President’s Budget.

- Dr. Romer said this morning that the Administration still expects positive GDP growth “in the second half of this year.”

A counterpoint to the President’s health care reform email

Yesterday President Obama sent an email on health care reform to the White House mailing list.

Respectfully, here is my counterpoint.

From: Keith Hennessey

Sent: Thursday, July 30, 2009 2:00 PM

To: Taxpayers

Subject: What health insurance reform means for you

Dear Taxpayer,

If you’re like most Americans, you like the health insurance you have today but think the system needs improvement. You would like things to work better, but are aware of the threats that arise from politicians who promise you something for nothing.

President Obama is correct that the underlying problem with health care is rising costs. Because of this problem, your paycheck grows more slowly, millions of Americans cannot afford to buy health insurance, and the escalating costs of Medicare and Medicaid will force enormous tax increases onto you and your children. The President wants to slow the growth of health care spending, and so do I.

Congress has gone in the opposite direction. Rather than changing incentives to reduce the cost of health insurance, they are trying to shift those costs onto someone else: you. The facts are not in dispute. The bill being developed in the House of Representatives would mean:

- No reduction in the growth of average private health insurance premiums;

- More than $1 trillion of new government spending over the next decade;

- $239 billion more debt in the short run, with ever-increasing additions to the deficit forever; and

- More than $500 billion of tax increases, including higher income tax rates on successful small businesses.

The U.S. economy is struggling to recover from a deep recession. America cannot afford a bill that imposes these extra burdens on an already weak economy. Rising health care costs are the problem, and so Congress’ solution begins by spending a trillion dollars more on health care. That doesn’t make sense.

The President is correct that it’s time to fix our unsustainable health insurance system. I disagree with the way that Congress is trying to fix it.

You will soon hear that these bills would not increase government involvement in your health care. That is incorrect. These bills give government officials authority to determine benefit packages, copayments and deductibles, relative premiums, as well as health plan expenses and profits. The government would, in effect, control health insurance. That’s the wrong way to fix a flawed health insurance system. There is a better way.

Health insurers today are partially insulated from competitive forces. If they convince the human resources manager at your employer to offer their plan, they’re all set. Your choice is secondary and therefore less important. We need a system that instead forces health insurance companies to compete for your business.

You can’t watch a televised sports event without being overwhelmed by the competition among auto insurers. They compete based on reliability and service when you have an accident and need help. They offer incentives for safe driving. Some emphasize that they can cover you even if you are a high-risk driver with a less-than-perfect driving record. They aggressively cut premiums to attract new customers. They reassure you that you’re “in good hands” if you choose to give them your premium dollars. These insurers don’t behave this way because they’re nice. They do it because it’s how they win your business, and because they know you will go elsewhere if you can get better value. Your health is both different and more important than your car, and we need to bring those same benefits to the health insurance market. We need a thoughtfully regulated market that means insurers will compete for your business by offering reliable, high quality health insurance that you can afford.

When insurers have to compete for your business, it will put you and your doctor in control, rather than your insurer or your employer. The bills moving through Congress assume that we all have the same health care needs, and they create one-size-fits-all solutions. But your situation is different from your neighbor’s, and only you can make the right decisions for you and your family, based on advice from medical professionals you trust.

This does not mean you’ll have to negotiate prices in the ambulance. Health insurance must protect you and your family when you need it most – when there is an emergency, or a severe accident or disease that threatens not only your family’s health, but your family savings. We buy insurance to protect ourselves against the small chance of a really bad situation, and that’s what health insurance must do.

More control means putting the resources in your hands while giving you both the information you need to make good decisions, and the incentives to consider whether that fourth MRI is really necessary, or whether you could save some money with a generic drug or a semi-private recovery room in the hospital, instead of a more expensive alternative. Health care and health insurance cost a lot today primarily because we’re often spending someone else’s money, so we don’t think about the cost of the care that we use. These tradeoffs and decisions about what care is worth the cost must happen. We must answer a basic question: who is more likely to make good decisions about your health insurance and health care – you and your doctor, or a government bureaucrat who doesn’t know or care about your particular situation?

The right kind of health care reform is not a free lunch. It carries obligations as well. While others offer you the hollow promise of government-provided and underfunded health care security, I’m telling you that you’re going to have to take more responsibility for decisions about your own health. A well-functioning system will offer financial incentives to keep yourself healthy, and to avoid risky behaviors that are the source of so much of the costs in today’s system. You will have to spend more time talking with your doctor and making hard choices yourself, although that’s far preferable to spending that time fighting with your insurer or with a government bureaucracy. You will have to shop intelligently for health insurance and decide what tradeoffs make sense for your family situation. You will have lower insurance premiums but more financially responsibility for relatively minor medical costs, and you can have a tax-free reserve fund that you can spend wisely on everyday non-critical medical expenses. It means more personal responsibility and control, and less dependence on the government. It means your health security comes from you buying insurance to protect your family against catastrophe, rather than hoping the government won’t ration your care when it’s needed. Others want to tell you that you have the right to have someone else pay for your health insurance. I think you have the responsibility to provide for your family’s health security, and that it’s government’s job to set rules so that you have affordable options, and to subsidize the poorest who cannot afford basic catastrophic protection.

The right kind of health care reform means your wages will grow faster as insurance premium growth slows. It means portable health insurance that you can take with you from one job to another, so you don’t get locked into your current job because you’re afraid to lose your health insurance. It means that millions more Americans will be insured because premiums are less expensive and the uninsured can better afford to buy it, not because we are shifting those costs onto other hard-working Americans and small businesses through higher taxes. It means no increase in the short-term budget deficit. It means dramatic reductions in unsustainable long-term budget deficits, rather than the explosive deficit increases contained in the current legislation.

The President is promising to guarantee your health care security by changing the way health insurance works and making someone else pay for it. If you’re reading this, you’re probably that someone else. You’ll probably pay for it through higher insurance premiums, as they do in New Jersey where these “protections” make insurance unaffordable for many. You’ll probably pay for it through higher taxes, whether you’re one of the eight million people who would remain uninsured and still pay higher taxes under the House bill, or a successful small business owner who would face higher income tax rates that kill your ability to grow your business. You and your kids will definitely pay for it through higher taxes when the massive deficit increases from this bill come due, on top of the unresolved long-term problems of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.

Over the next month you will hear the claim that opponents of the pending Congressional health care bills are defenders of the status quo. You are going to hear that the choice is between a broken system and these bills, and that reform is better than no reform. You will hear that the cost of doing nothing is too high, and that we must therefore enact one particular solution, no matter how flawed.

This is misleading, and there is a better way. I strongly oppose the health care bills now being advanced in Congress, and I think the status quo is a mess. There is no free lunch in health care reform, and fixing our current system without breaking the good parts will involve some hard choices. There are alternatives to the pending bills that do health care reform the right way. I have a plan you can find at KeithHennessey.com. If you’d rather see a good plan from someone who actually matters, then check out the Ryan-Coburn Patients’ Choice Act from Rep. Paul Ryan and Senator Tom Coburn.

You will soon be told that it’s time to act, and that we must therefore enact the wrong kind of reform. You can help by telling your friends, your family, and the rest of your social network that Washington needs instead to start over, and to put you, the patient/worker/taxpayer/consumer/citizen, at the center of health care decision-making, not the government. We need the right kind of health care reform, not these bills now being considered.

Washington – Please stop promising us free lunches. The country is going bankrupt – don’t make it any worse. We’re adults. We can handle the hard choices.

Sincerely,

Keith Hennessey

President Obama’s health care reform email

Here is the email that President Obama sent yesterday to the White House email mailing list.

I have written a counterpoint.

From: President Barack Obama

To: John Doe

Subject: What health insurance reform means for you

Dear Friend,

If you’re like most Americans, there’s nothing more important to you about health care than peace of mind.

Given the status quo, that’s understandable. The current system often denies insurance due to pre-existing conditions, charges steep out-of-pocket fees – and sometimes isn’t there at all if you become seriously ill.

It’s time to fix our unsustainable insurance system and create a new foundation for health care security. That means guaranteeing your health care security and stability with eight basic consumer protections:

- No discrimination for pre-existing conditions

- No exorbitant out-of-pocket expenses, deductibles or co-pays

- No cost-sharing for preventive care

- No dropping of coverage if you become seriously ill

- No gender discrimination

- No annual or lifetime caps on coverage

- Extended coverage for young adults

- Guaranteed insurance renewal so long as premiums are paid

Learn more about these consumer protections at Whitehouse.gov.

Over the next month there is going to be an avalanche of misinformation and scare tactics from those seeking to perpetuate the status quo. But we know the cost of doing nothing is too high. Health care costs will double over the next decade, millions more will become uninsured, and state and local governments will go bankrupt.

It’s time to act and reform health insurance, drive down costs and guarantee the health care security and stability of every American family. You can help by putting these core principles of reform in the hands of your friends, your family, and the rest of your social network.

Thank you,

Barack Obama

Hennessey’s health care reform plan, v2

President Obama has sent a letter to his White House mailing list that warns against “an avalanche of misinformation and scare tactics from those seeking to perpetuate the status quo.”

I am not one of those people. I can’t stand the health policy status quo, and I think there is a better way to reform our health care system than the plans now moving through Congress.

I have written extensively about both what is wrong with the status quo, and with my concerns about the legislation supported by our President. I will continue to try to contribute verifiable information and analysis to raise the level of policy debate.

To demonstrate that I do not favor the status quo, here is version 2 of my desired health care reform. I’m adding a little more detail from v1, but want to keep this description high-level so we don’t get bogged down in second-order details. Without further ado, here is

Keith Hennessey’s health care reform plan (v2)

Do:

- Repeal the current law tax exclusion for employer provided health insurance, and replace it with a $7,500 (single) / $15K (family) flat deduction for buying health insurance.

- The deduction is independent of the premium cost. If you buy a $5,000 individual policy, you get a $7,500 deduction. If you buy a $10,000 individual policy, you get the same $7,500 deduction.

- The overwhelming majority of premiums fall under these threshholds, so 100m+ people would pay lower taxes.

- The minority with premiums above these thresholds would pay higher taxes.

- In total the government does not collect more revenue, although the tax burden shifts to those with high-cost policies.

- Index the thresholds to inflation (CPI). This bites more tightly over time. I’d funnel the long-term increased revenues into some broad-based tax relief to stay revenue-neutral over time.

- Allow the purchase of health insurance sold anywhere in the U.S.

- This would force States to compete for the right regulatory balance of consumer protection and premium cost.

- Rep. John Shadegg has a bill that does this.

- Make health insurance portable

- This requires relatively small tweaks to law, but insurers would need to develop new portable insurance plans that you could take with you from one job to the next. The policy change is easy. Getting employers and insurers to change their long-standing business models is hard.

- Expand Health Savings Accounts

- Allow higher contribution limits, and allow financially equivalent coinsurance structures driven by market demand. Continue to mandate an initial deductible and catastrophic protection. No benefit-specific exemptions as advocated by some.

- Aggressively reform medical liability

- aka “medical tort reform.” Details TBD.

- Aggressively slow Medicare and Medicaid spending growth, and use the savings for long-term deficit reduction

- Details TBD.

- Assume that my package would be significantly more aggressive (“deeper cuts,” in the language of opponents) than anything being discussed in Congress today.

Don’t:

- Raise taxes

- Create a new government health entitlement

- Mandate the purchase of health insurance

- Mandate that employers provide health insurance to their employees

- Have government set private premiums

- Create a government-run health plan option

- Have the government mandate benefits

- Expand Medicaid

Results:

- Lower premiums, higher wages

- Portable health insurance reduces “job lock”

- +5 million insured (net)

- 100 million people will pay lower taxes

- 30m with expensive health plans pay higher taxes

- No net tax increase overall

- Reduces short-term and long-term deficit

- Fair to small business employees & self-employed

- Incentives and individual decisions “bend the cost curve down”

- More individual control & responsibility for medical decisions

CBO calls a TKO on the House health bill

In a letter to four key Republican Congressmen (Camp, Barton, Kline, and Ryan), the Congressional Budget Office destroys the House Democrats’ implementation of the President’s goal of long-term fiscal responsibility through health care reform. With this analysis the fight about the House bill is over by a technical knockout (TKO). The proposed income tax increases were the key vulnerability. I will walk you through the analysis and why I reach the following conclusion.

Conclusion: CBO says that because the proposed new health spending would grow faster than the proposed new income tax increases, the House health bill would increase the long-term deficit. Since the President has said he would not sign a bill that increases the long-term deficit, the bill is dead in its current form. Any tax increase that would grow more slowly than the proposed new spending faces the same irreconcilable problem. The only way to solve this problem and meet the President’s long-term goal is to cut health spending or tax employer-provided health insurance.

We can start by looking at the short-term budget effects of the House Tri-Committee health bill over the next ten years:

|

10-year deficit effect |

|

| New coverage provisions |

+ $1,042 billion |

| Medicare savings |

– $219 billion |

| Other provisions (primarily income tax increases) |

– $583 billion |

| Net deficit increases |

+ $239 billion |

The new CBO information is about the long run deficit. Here is the key paragraph from the 18 page CBO letter:

Looking ahead to the decade beyond 2019, CBO tries to evaluate the rate at which the budgetary impact of each of those broad categories would be likely to change over time. The net cost of the coverage provisions would be growing at a rate of more than 8 percent per year in nominal terms between 2017 and 2019; we would anticipate a similar trend in the subsequent decade. The reductions in direct spending would also be larger in the second decade than in the first, and they would represent an increasing share of spending on Medicare over that period; however, they would be much smaller at the end of the 10-year budget window than the cost of the coverage provisions, so they would not be likely to keep pace in dollar terms with the rising cost of the coverage expansion. Revenue from the surcharge on high-income individuals would be growing at about 5 percent per year in nominal terms between 2017 and 2019; that component would continue to grow at a slower rate than the cost of the coverage expansion in the following decade. In sum, relative to current law, the proposal would probably generate substantial increases in federal budget deficits during the decade beyond the current 10-year budget window.

In the long run, it’s all about growth rates. Let’s go to the chalkboard. All numbers are from CBO’s July 14th estimate of the House bill, Joint Tax Committee’s July 16th estimate, and CBO’s July 26th letter to Mr. Camp.

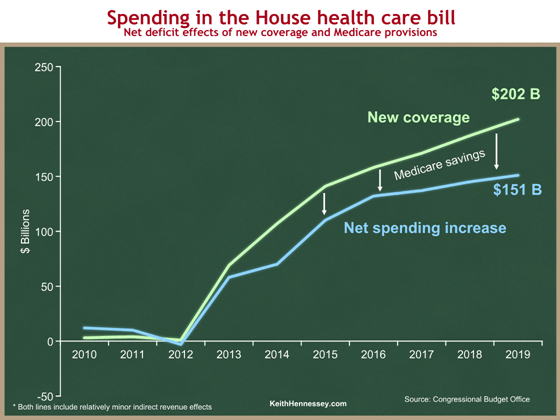

We start with the short run, and look just at the new coverage provisions in green, and the net spending increase in blue. Proposed Medicare savings bring the gross new coverage spending of the green line down to the net spending increase of the blue line. As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

Spending would start in 2013 and ramp up to its long-term path by 2015. In 2019 the bill spends $202 B on the new coverage provisions and saves $51 B from Medicare, for a net spending increase of $151 B.

A small caveat: both the new coverage section of the CBO estimate and the Medicare savings include some indirect revenue effects, such as the higher taxes that would be collected from individuals and employers who don’t comply with the mandates. So technically these lines show the net deficit effects of the “New coverage” and Medicare sections of the bill. The revenue components are relatively small, and this oversimplification does not affect the analysis, so I’m labeling the blue line “net spending increase.” In addition, this is how CBO packages things, so I am confident it’s a safe oversimplification.

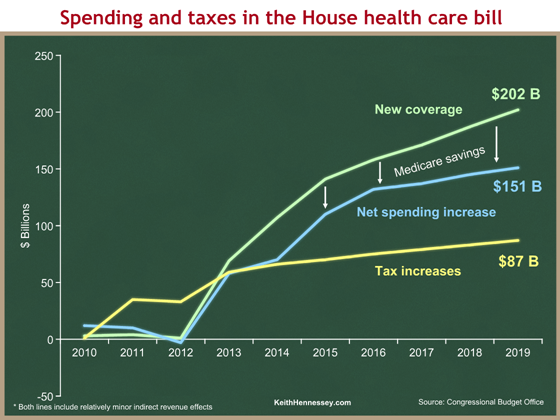

Now let’s add to the graph the tax increases in the House bill as a new yellow line. Everything else is the same as on the first graph.

The House bill raises $87 B of taxes in 2019, compared to the $151 B net spending increase in that year. The area between the light blue and yellow lines is the deficit impact. Up to 2013, the bill collects more in taxes than it spends, so the bill actually reduces budget deficits in the early years. After 2013, the light blue net spending line is above the yellow tax line, so the bill adds to the deficit. In 2019, the bill increases the deficit by $151 B – $87 B = $64 B. The net of the deficit-reducing and deficit-increasing areas is the $239 B deficit increase over 10 years from the first table above. Again, all of these are CBO and Joint Tax Committee numbers.

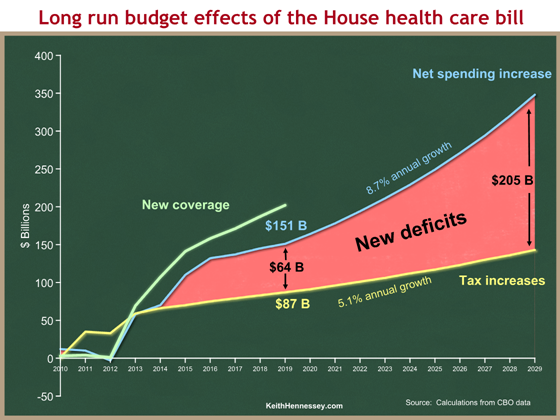

Now we turn to the long run, relying on that key CBO paragraph. Here are the key numbers:

The net cost of the coverage provisions would be growing at a rate of more than 8 percent per year in nominal terms between 2017 and 2019; we would anticipate a similar trend in the subsequent decade. … Revenue from the surcharge on high-income individuals would be growing at about 5 percent per year in nominal terms between 2017 and 2019; that component would continue to grow at a slower rate than the cost of the coverage expansion in the following decade.

CBO phrases this a little bit carefully, so I want to be clear that this last graph represents my interpretation of the above language, rather than explicit calculations provided by CBO. I’m going to extend the blue and yellow lines from the graph above through the second decade.

Here are some details for the technicians:

- All figures through 2019 are from CBO’s July 14th estimate and Joint Tax’s July 16th estimate.

- The average annual growth rate of the yellow line from 2017 to 2019 is 5.1%, derived from the JCT July 16th estimate.

- Beyond 2019, the yellow line is the 2019 figure of $87 B from Joint Tax, grown at a 5.1% annual rate.

- The average annual growth rate of the blue line from 2017 to 2019 is 8.7%, derived from the CBO July 14th estimate.

- Beyond 2019, the blue line is the 2019 figure of $151 B, grown at an 8.7% annual rate.

- The $205 B deficit increase in 2029 is simply the delta between the two calculated points for that date.

I am being a little more precise than CBO’s language. They were careful not to explicitly say that the growth rates would be precisely 8.7% and 5.1% over the next decade, but it’s the most reasonable conclusion from their language if you have to pick numbers. It’s not fair to say that the $205 B figure is a CBO number — it’s not. It is fair to say that the ever-widening red area, representing large and increasing long-term deficit increases, represents CBO’s conclusion.

What does this mean?

This is the most important analysis CBO has done of the House health bill.

Remember the President’s three part test:

- A bill should not increase the budget deficit in the short run (the first ten years).

- A bill should not increase the budget deficit in the tenth year.

- A bill should “bend the health cost curve down” in the long run. (More recently, a weaker test that a bill must not increase long-term deficits.)

I would prefer stronger tests, which I proposed six weeks ago.

The second graph demonstrates that the House bill would fail the first two tests. CBO and Joint Tax said that in their July 14th and July 16th estimates. The House bill increases deficits by $239 B over the next decade, and by $64 B in the tenth year.

The new information is CBO’s conclusion that the House bill would increase long-term budget deficits, because the new spending will grow faster than the income tax increases. This is logical: if the net spending increases start the second decade $64 B higher than the tax increases, and if the spending will grow 8.7% per year while the taxes will grow only 5.1% per year, then the gap between the two, the budget deficit, will only grow over time. CBO has concluded that the House bill would make America’s long-term deficit problem dramatically worse than it is under current law. This clearly fails the third Presidential test.

There’s another conclusion that is implicit in CBO’s analysis. Because of the different growth rates, there is no way to solve this problem by raising income taxes like the House bill does. If you want to include tax increases in your bill, they have to match the net spending increase in the tenth year, and they have to grow at least as fast as the 8.7% growth rate of long-term net spending. The only thing that has a chance of doing that is the taxation of health benefits.

I think this is fatal to the House bill. The income tax increases were already in serious trouble because of opposition from Blue Dog Democrats who do not want to raise taxes on small business owners, and who do not want to be BTU’d (again) by Senate Democrats who have said they won’t raise income taxes. But House Democratic Leaders were relying on these tax increases to avoid having to make deeper entitlement spending cuts, tax employer-provided health insurance, or dramatically scale back their proposed new spending. CBO has called the fight over by a technical knockout.

Where have I heard this before?

If you are patient enough to have read this blog over the past few months, some of this may look familiar to you. Here’s what I wrote on June 12:

It is therefore odd and self-contradictory that they have proposed raising taxes to offset the higher spending of a new health care entitlement for the uninsured. While you can technically meet my short-term Test 1 by doing so (in a Blue Dog / centrist way that I would oppose, but you’d meet it), it is mathematically impossible in the long run to offset a new health care entitlement with higher taxes, unless your bill also slows the growth of health care spending in other ways.

Responding to the Vice President’s op-ed

The Vice President wrote an op-ed in Sunday’s New York Times, “What you might not know about the recovery.” He wrote:

<

blockquote>the

That’s an unfortunate word choice. Here is dictionary.com’s definition:

jolt: to jar, shake, or cause or move by or as if by a sudden rough thrust; shake up roughly

And yet heres the President last November 24th:

… we need a big stimulus package that will jolt the economy back into shape …

… we have to make sure that the stimulus is significant enough that it really gives a jolt to the economy …

And so we are going to do what’s required to jolt this — this economy back — back into shape.

And again on February 9th in a press conference:

But at this particular moment, with the private sector so weakened by this recession, the federal government is the only entity left with the resources to jolt our economy back to life.

Here’s the Vice President, on March 28th in Chile:

The Recovery Act, as we call it, provides a necessary jolt to our economy to implement what we refer as “shovel-ready” projects …

And again on June 2nd in a stimulus roundtable:

And, of course, we also came forward with what we’re going to talk about today, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, an initial big jolt to give the economy a real head start.

(hat tip to Don Stewart)

My intent is not merely to point out the contradictory language, but to focus attention (again) on the question of stimulus timing. The Vice President sets up some straw man criticisms of the stimulus law that exclude my own:

It is true that the act’s effort to address multiple problems simultaneously makes it an easy target for second-guessing. Critics have argued that the tax cuts are too small (or too large); that too much (or not enough) aid is going to rural areas; that too little (or too much) is being spent on roads. Recently, some have even criticized the act for helping support soup kitchens and food banks.

I have a different critique. I believe the stimulus law will increase GDP. It will just do it later than we need it to.

The Vice President addresses this concern in his op-ed:

The bottom line is that two-thirds of the Recovery Act doesn’t finance “programs,” but goes directly to tax cuts, state governments and families in need, without red tape or delays.

This is a sleight-of-hand to argue that the stimulus funds are being spent quickly. If two-thirds of the funds are being spent without red tape or delays, then there is no problem.

If instead we separate out the aid to state governments, things look quite different.

A quick review of the CBO score of H.R. 1, the stimulus law, shows:

|

10-year deficit effect ($B) |

|

| “Tax cuts” |

215 |

| Unemployment Insurance |

39 |

| TANF (welfare) & Child support |

18 |

| Food stamps |

20 |

| Health insurance subsidies |

25 |

| Related tax benefits for individuals |

1 |

| Total, “tax cuts” and benefits to individuals |

$318 B |

I put “tax cuts” in quotes because I think much of this funding is mislabeled. If the government sends you a check and you’re still paying the same amount of taxes, that’s not a tax cut. That’s an entitlement check. That’s a separate question from today’s debate, so I will set it aside.

So $318 B of the total stimulus is in the form of “tax cuts” or payments to individuals. These funds get into people’s hands quickly. If you’re going to do fiscal stimulus, this is how I would prefer you do it, setting aside for the moment distributional questions.

While the net deficit impact of H.R. 1 over ten years is the well-known $787 B figure, the macroeconomic stimulus is actually a little bigger, about $810 B over ten years. That’s because the bill would actually reduce spending in years 7 through 10. So the $787 B is $810 B of deficit-increasing policies, followed by about $23 B of deficit-reducing policies.

$318 B divided by $810 B is about 39 percent.

Now let’s look at aid to states. It’s hard to tease this out precisely from the CBO table, but we can get a ballpark figure:

|

10-year deficit effect ($B) |

|

| State Fiscal Relief |

90 |

| State Fiscal Stabilization Fund |

54 |

| Highway Construction |

28 |

| Other Transportation |

21 |

| Housing |

13 |

| Education |

25 |

| Law Enforcement Assistance |

3 |

| Total, aid to states & locals |

234 B |

(Budgeteers: I would appreciate corrections to the above table. I’m assuming that IDEA and Special Ed all go to S&L. Is that right?)

So roughly another $234 B comprises transfers from the Federal government to State & Local governments. That’s about 29% of the total $810 B stimulus impact. This is where the Vice President’s “without red tape or delays” argument breaks down, for two reasons.

- When the Federal government gives a dollar to a State or local government, GDP does not increase. That’s just a transfer from one level of government to another. It’s not increasing the size of the government until the State or local government gives that dollar to someone providing a good or a service – a highway road worker, a teacher, or a citizen receiving a tax cut or an entitlement check. So there is a lag introduced when money passes from the Federal government, through State and local governments, into the economy. I don’t see how the Vice President can say that funds transferred from the Federal government to State and local bureaucracies enter the economy “without red tape or delay.”

- States don’t take all the funds they receive from the Feds and pump it into the economy.

Example: State A will face a $2 B budget deficit this year. The Feds pay State A $4 B from the stimulus. State A increases spending from $3 B relative to what they had planned, and they cut their budget deficit in half. From a macroeconomic stimulus perspective, 25% of the Federal government’s stimulus was lost to reduce the State’s budget deficit.

Here then is my summary comparison:

Vice President Biden: The bottom line is that two-thirds of the Recovery Act doesn’t finance “programs,” but goes directly to tax cuts, state governments and families in need, without red tape or delays.

Hennessey: The bottom line is that 39% of the Recovery Act goes to payments to individuals without red tape or delays. About 29% goes to State and local governments, where it faces State and local red tape and delays, and where some of it is siphoned off to reduce State budget deficits rather than provide macroeconomic stimulus. The other roughly 32% flows through slow-spending Federal bureaucracies.

We need the macroeconomic benefits of the stimulus now. The Administration is in a box because they want to argue that the economy has improved because of their policies, and that the stimulus has contributed to that improvement, but they cannot show that enough stimulus money has yet entered the economy to have a measurable effect.

CBO kills the President’s Medicare commission proposal

CBO has evaluated the Administration’s legislative proposal to create an “Independent Medicare Advisory Council” (IMAC) in the Executive Branch. The IMAC would be a group of five doctors or people with “specialized expertise in medicine or health care policy,” appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. They would have two tasks:

- Recommend how much to increase payment rates for different types of Medicare providers (hospitals, doctors, home health care providers, medical equipment, nursing facilities) each year; and

- Recommend “broader Medicare reforms” that “improve the quality of medical care” or “improve the efficiency of Medicare.”

In both cases, the Council would be limited to making recommendations that do not increase Medicare spending. There is no requirement that the IMAC’s recommendations save any money.

The proposal creates a fast-track process in which the President has to send the council’s recommendations to Congress with a binary yes-or-no recommendation. If the President approves the recommendations, he would have the authority to implement them unless both Houses of Congress voted to stop him within 30 days. The details of the Congressional disapproval procedure mean that you would effectively need at least one more vote than 2/3 of the House and 2/3 of the Senate to overrule recommendations made by the IMAC and approved by the President.

This would be an enormous transfer of policymaking authority and power from Congress to the Executive Branch. There are all sorts of fascinating balance-of-power and interest group politics dynamics to analyze, and I’m going to completely ignore them to focus on the money.

The Administration proposed this because moderate/conservative House Democrats (aka “Blue Dogs”) told the President they would not support the House Tri-Committee health care bill unless it were changed to more aggressively address the long-term federal health spending problem (which the Tri-Committee bill would exacerbate).

In addition, the President frequently talks about the need to “bend the health cost curve down” in the long run. There are two related health cost curves – one for government health spending, and one for private health spending by individuals, families, and businesses. The Blue Dogs focused primarily on bending the long-term government health cost curve down, and so the President gave them the IMAC. The Administration has been playing with the idea for a while, but it got legs last week because Speaker Pelosi needs Blue Dog support for the Tri-Committee bill.

And yet the Administration’s IMAC proposal is drafted in a way that does not force any spending cuts, but instead sets a goal only of not increasing Medicare spending. In addition, Budget Director Orszag’s letter to the Speaker contains a weaker deficit reduction goal than previously stated by the President. Here’s Director Orszag’s new language:

We agree that it is critical that health care reform is not only deficit neutral over the next decade, but that it does not add to our deficits thereafter.

What happened to bending the long-term cost curve down? Director Orszag’s letter weakens the test to “We won’t increase the deficit.” This means that if a bill “raises the health cost curve,” as Director Elmendorf says about the pending legislation, the Administration is OK, as long as they increase taxes so that the net does not increase the long-term budget deficit. The Administration’s legislative proposal matches this rhetoric. They are lowering the bar.

I will guess that there is a struggle both within the Administration and among Capitol Hill Democrats between the small deficit reduction crowd and the much larger “don’t cut health care providers” crowd, and that this weakened language represents a new balance point in that struggle. It’s odd, because it’s in an Orszag letter, and it’s inconsistent with the President’s and his consistent message that we need long-term deficit reduction, aka “health care reform is entitlement reform.”

CBO concluded the President’s IMAC proposal would save very little money in either the short run or the long run.

Here is CBO Director Elmendorf in a letter to House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer:

CBO estimates that enacting the proposal, as drafted, would yield savings of $2 billion over the 2010-2019 period (with all of the savings realized in fiscal years 2016 through 2019) if the proposal was added to H.R. 3200, the America’s Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009, as introduced in the House of Representatives.

To put $2 billion of Medicare savings over four years in perspective:

- It would be a 0.07% reduction. That’s seven-hundredths of one percent. CBO estimates Medicare spending over that same four-year period to be $2.87 trillion.

- It’s five times as large, on an annual basis, as the much-mocked $100 million of savings the President asked his Cabinet Secretaries to find. (Where are those savings, by the way? Still waiting.)

CBO’s estimate is a “probabilistic score.” They look at various possible scenarios and figure out how much money would be saved under each. They then guess at how likely each outcome is, and the $2 B is the probability-weighted average (the “expected value”) of the savings under the various possible scenarios. CBO explains it this way:

This estimate represents the expected value of the 10-year savings from the proposal: In CBO’s judgment, the probability is high that no savings would be realized, for reasons discussed below, but there is also a chance that substantial savings might be realized.

OMB Director Orszag has attempted to portray CBO’s analysis as a win: (emphasis added)

In part because legislation under consideration already includes substantial savings in Medicare over the next decade, CBO found modest additional medium-term savings from this proposal — $2 billion over 10 years. The point of the proposal, however, was never to generate savings over the next decade. (Indeed, under the Administration’s approach, the IMAC system would not even begin to make recommendations until 2015.) Instead, the goal is to provide a mechanism for improving quality of care for beneficiaries and reducing costs over the long term. In other words, in the terminology of our belt-and-suspenders approach to a fiscally responsible health reform, the IMAC is a game changer not a scoreable offset.

Director Orszag is correct that the Administration’s stated goal of the IMAC proposal, as expressed in both his letter to Speaker Pelosi and the substance of the proposal, is not to generate significant short-term savings. The constraint on the council does not require them to reduce spending at all.

House Democratic leaders, however, need two things from the IMAC proposal:

- They need scorable short-term savings so they can pay for their $1+ trillion of proposed new spending.

- They need to convince the Blue Dogs to support their bill. The Blue Dogs didn’t ask the President for a proposal that would transfer enormous authority from Congress to the Executive Branch so that quality of care could be improved. They asked him for a proposal that would bend the government health care cost curve down – a proposal that would produce scorable long-term savings to make it easier for them to vote for a health care bill that would increase government spending, taxes, and deficits.

Director Orszag says one goal of the IMAC proposal is “reducing costs over the long term,” even though there is no requirement in the language that the council’s long-term recommendations do anything other than not increase Medicare spending. At the same time, his claim that IMAC is a game changer that would reduce costs over the long term contradicts CBO.

Here’s Director Orszag: “Instead, the goal is … and reducing costs over the long term. … the IMAC is a game changer not a scoreable offset.”

And here is CBO Director Elmendeorf’s letter to House Majority Leader Hoyer:

Looking beyond the 10-year budget window, CBO expects that this proposal would generate larger but still modest savings on the same probabilistic basis.

This is a direct contradiction. Director Orszag says the proposal is a long-run “game changer” whose goals include “reducing costs over the long term,” while CBO says the proposal “would generate larger but still modest savings” beyond the 10-year budget window. In this context, “larger” means “larger than 0.07%.”

The Elmendorf letter explains in further detail why CBO believes the IMAC proposal will generate only “modest” savings in the short and long run.

The proposed legislation states that IMAC’s recommendations cannot generate increased Medicare expenditures, but it does not explicitly direct the council to reduce such expenditures nor does it establish any target for such reductions.

As proposed, the composition of the council could be weighted toward medical providers who might not be inclined to recommend cuts in payments to providers or significant changes to the delivery system.

Outside influence on the council and the President, however, might make it politically difficult to recommend and implement reforms that could be viewed as undesirable by interested parties. Medical providers, beneficiaries, and Members of Congress would probably exert considerable pressure on both IMAC and the President to balance recommendations for savings against beneficiaries� concerns about the costs and availability of medical services and the interests of those receiving Medicare payments for delivering services.

Expected savings from the IMAC proposal would grow after 2019, but many of the above points would still apply, reducing the likelihood of attaining large annual savings. The considerable uncertainty about the amount of savings that might occur within the first 10-year projection period would compound in future decades. Although it is possible that savings would grow significantly after 2019, CBO concludes that the probability of this outcome is low for the proposal as drafted, particularly because there is no fall-back mechanism to ensure some minimum level of spending cuts beyond those already included in H.R. 3200.

Director Orszag calls the lack of a fall-back mechanism to ensure some minimum level of spending cuts a “tweak,” and cleverly but misleadingly implies that CBO says the Administration’s IMAC proposal would be effective:

With regard to the long-term impact, CBO suggested that the proposal, with several specific tweaks that would strengthen its operations, could generate significant savings. … The bottom line is that it is very rare for CBO to conclude that a specific legislative proposal would generate significant long-term savings so it is noteworthy that, with some modifications, CBO reached such a conclusion with regard to the IMAC concept.

No, they did not reach such a conclusion. Note his use of the word “concept” rather than “proposal.” Here’s what CBO actually said:

Looking beyond 2019, a much stronger IMAC-type proposal could reap considerably more savings, depending on which specific features identified above were included and how those features were crafted in legislation. In particular, if the legislation were to provide IMAC with broad authority, establish ambitious but feasible savings targets, and create a clear fall-back mechanism for instituting across-the-board reductions in net Medicare outlays, CBO believes the council would identify steps that could eventually achieve annual savings equal to several percent of Medicare spending. In the absence of a fall-back mechanism, CBO expects that the probability that the President would approve recommended changes that would lead to such significant savings would be lower.

CBO is describing a fundamentally different kind of proposal. The Administration’s proposal would give the IMAC authority to reshuffle spending, and authority to cut spending, but would not require it to cut spending. CBO is saying that if legislation requires spending cuts and specifies the amounts of those spending cuts, and if it creates an automatic mechanism to enforce those spending cuts in case the IMAC does not recommend any cuts, then an IMAC can be effective. In this kind of proposal, the IMAC’s recommendations don’t cause the long-term savings. The other parts of the bill do.

As a friend said to me, “At some point the advocates of this reform package need to realize that the only way to cut spending is to cut spending.”

With this letter CBO has killed the President’s IMAC proposal. It almost certainly would have died even without CBO’s letter. The proposal would have transferred an enormous amount of power from Congress to the Executive Branch. Turf-conscious Congressional committee chairmen would have fought it to protect their power base. Medicare provider interest groups (hospitals, doctors) were starting to lobby against it. They prefer Congress making these decisions because they’re easier to lobby and influence.

The only chance IMAC had was if CBO had said it would save gobs of money, allowing House leaders simultaneously to make Blue Dogs happy for being fiscally responsible, and to remove from their bill other, more politically painful, spending cuts or tax increases. IMAC was drafted so weakly that it became a budget gimmick. On Friday I wrote:

Congress usually looks first to gimmicks, but the President’s unintentional elevation of the actually honest CBO Director makes that harder than usual.

Yes, the Administration could submit a fundamentally different proposal and call it a “tweak” of their existing one. To achieve the stated goals of bending the government health cost curve down and reducing future deficits, such a proposal would need to actually cut spending in an enforcable and unavoidable way. If they want to throw in a new council to shuffle money around within the mandated lower levels, that’s a separable question. The President’s advisors know, however, that a proposal like this with real teeth would never get off the ground in Congress. That’s too bad, because we desperately need the long-term deficit reduction.

The death of IMAC is a black eye for the Administration and another step backward for the pending health care reform bills. This result was both predictable and avoidable.

(Photo credit: That 70’s Crime Show Opening Sequence by jcoterhals)

More health care stumbling by Team Obama

Kim Strassel once again outshines the crowd in today’s must-read Wall Street Journal column, “How Obama Stumbled on Health Care.”

All Democrats have to do is agree on something. That they can’t is testimony to Team Obama’s mismanagement of its first big legislative project. The president is a skilled politician and orator, but the real test of a new administration is whether it can shepherd a high-stakes bill through Congress.

Kim brilliantly identifies four key mistakes made by the President and his team in their health care legislative effort. I suggest you read her analysis, then return here for my supplement. Go. Read it now. I’ll wait here until you return.

After six months the Administration is one for three on major domestic legislative initiatives. They had a quick legislative win with stimulus, but despite all their work to manage macroeconomic expectations, they are fighting a rearguard action against a growing perception that the stimulus has failed. They rammed a carbon cap bill through the House at some political cost, which now languishes and will likely die a quiet death in the Senate. And Thursday could not possibly have gone worse for the White House. The day after the President tried to restore forward momentum with his health care press conference, the press chattered instead about the Cambridge police while Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid explicitly acknowledged what everyone in Washington already knew: both legislative bodies may miss the President’s health care deadline. Nobody expected the Senate to pass a bill before the August recess, but if the House fails as well, then the President faces not just a loss of momentum, but momentum in reverse. That is why I anticipate a few more twists and turns in the House before the recess. Who knows – maybe the Speaker can pull things together.

Here are six additional health care stumbles by Team Obama, rounding out Kim’s list to an even ten.

- They still have not chosen a strategy:Does the President want a Democrat-only bill that pleases the Left and passes the Senate with at most one or two Republican votes? Or does he want a bipartisan bill at the expense of the Left’s policy priorities? A bipartisan strategy can work only if the President is willing to negotiate directly with Republicans like Senators Grassley and Enzi, who are not so naive as to think that Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus has authority to negotiate for House Democrats or the President. Senators Grassley and Enzi are experienced enough to know that an early deal with just Chairman Baucus would unravel later in the legislative process when Republicans have less procedural leverage.Only an up-front negotiation between Republicans and the President can produce a deliverable bipartisan deal, but such a negotiation likely means no public option, no individual or employer mandate, no tax increases except for taxing health benefits (infuriating organized labor), much lower spending and real scorable long-term deficit reduction, and addressing social policy issues that anger some on the Left. It would be extremely painful for the President to break with his own party on these issues at the front end of the process.Without Presidential strategic guidance, House Democrats are running hard-left with the Tri-Committee bill as you would expect, while Senate Democrats tug between Senators Baucus and Conrad trying to create a centrist alliance without authority, and Senators Dodd, Rockefeller, and Schumer trying to keep the Senate bill from straying too far to the center. The result is chaos, confusion, and Democrat vs Democrat battles.

- They appear to think they control the agenda during a recession:Six months ago a surge of national optimism and stratospheric poll numbers convinced Team Obama that the President would set the policy agenda for 2009. He has more agenda-setting power than all other American politicians combined, but less agenda-setting power than an economy in severe recession. Sometimes unwanted external events drive the policy agenda for you (think 9/11, pirates, a financial crisis, Iran and North Korea). 2009 American domestic policy is not about health care reform or climate change. It’s still about returning the economy to a healthy growing state, and will be until the unemployment rate begins to decline. For the next several months, the President has less domestic agenda-setting power than the monthly employment report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.By claiming that the stimulus is working (you just can’t tell yet) and things will eventually get better (just be patient until next year) while 2.6 million jobs have been lost since January and the unemployment rate continues to climb, the President risks seeming out of touch on the most important domestic policy issue. Team Obama wants to derive legislative advantage from a serious crisis for long-standing liberal policy priorities. They need to focus on selling their macroeconomic strategy to avoid losing even more ground. This is beginning to undermine the President’s ability to convince members of his own party to take tough votes. It is easy to imagine Members of Congress going home in August to talk about health care reform, only to hear their constituents demand to talk about jobs and the still-weak economy.

This relates directly to one of the “perils of spin” identified by Kim:

Selling a huge expansion of government health care in the middle of a recession was never going to be easy. The Obama team hit on the argument that by adding to the government rolls, it would in fact save money and boost the economy. Bizarre as this claim was, it became the administration’s prime rationale for “reform.”

- They ignore the negative economic consequences of health care reform done wrong: In Washington the people who work on health care legislation are usually health policy experts. Team Obama forgot what Kim points out: health care reform is as much an economic issue as it is a health policy issue. While the debate first focused on the health policy question of the public option, it has now expanded to include broader economic policy questions. The Speaker wants Members to vote on a bill that would result in bigger budget deficits, higher taxes (on small businesses and eight million uninsured people), higher premiums that mean lower wages, a burdensome employer mandate leading to a less flexible workforce, and clunky new government bureaucracies to run it all. How can Speaker Pelosi expect House Democrats to vote for a bill that hurts the economy when the economy is weak? They already took one tough economic vote for climate change legislation only to see the Senate apparently ignore it. Neither the bill’s authors nor the Administration have satisfactory answers to the economic downsides of the specific policies in these bills, and they are losing the policy debate because of it. In the Bush White House we spent hundreds of man-hours anticipating policy attacks and preparing our responses in advance. The Obama Team seemed caught off guard when CBO Director Elmendorf said the bills move the deficit in the wrong direction.

- They are trying to finesse fundamental policy inconsistencies: The President still has not satisfactorily resolved at least three core policy inconsistencies. Large partisan Congressional majorities do not relieve you of the burden of making a coherent and internally consistent argument for your desired policy change, and the Administration has failed to do so. The President’s core problem definition is spot-on, but until he addresses these questions he will be unable to close the sale.

- If cost growth is the problem, why begin by expanding gross federal health spending by 16% and creating insurance mandates that will raise premiums? CBO said the former was a problem last December.

- Why did Team Obama predicate both their health and budget strategies on bending the long-term health cost curve down, and then knowingly propose policies that CBO says will instead only raise the cost curve? What made them think Congress would ignore CBO? The President correctly defined the underlying problem, but still has not offered a specific and credible solution to long-term private health care cost growth.

- The President campaigned against an individual mandate and against taxing employer-provided health benefits. The Left wants to do the former; moderate Democrats need the latter for a bipartisan deal. Few know where the President stands today on either policy. Team Obama cannot finesse these core policy choices and expect legislative progress.

- They are trying to do it all at once:Team Obama began this process with a surprising inside-the-Beltway tactic, I think to avoid a danger learned during the Clinton Health Plan battles. They encouraged Chairman Baucus to negotiate deals with insurers, drug companies, and health care providers, then triumphantly announced the support of these special interests at various Presidential events. It is unclear whether they thought interest group support would help enact a bill, or merely weaken the organized interest group opposition that helped kill the Clinton Health Plan in 1994. It’s an incredibly cynical tactic, given the President’s campaign against Washington special interests.But they are repeating one of the Clinton Administration’s core mistakes by trying to do massive health care reform in one big bite. For 15 years since the failure of the Clinton Health Plan, Democrats pursued an incremental approach. They gradually expanded Medicaid and created S-CHIP, putting conservatives on the defensive as they argued against incremental expansions of taxpayer-financed coverage to politically sympathetic populations. Team Obama instead reverted to the all-at-once approach of 1994, and they face some of the same challenges as Team Clinton did then.Shuffling $1 to $1.5 trillion (that’s 1,000 to 1,500 billion dollars) and creating new individual and employer mandates are massive policy proposals that would fundamentally reorder one-sixth of the U.S. economy. Redistributing this many resources creates big winners and losers, and those losers will fight legislatively. We can see this as Democrats argue about how to pay for such an enormous entitlement expansion. Having locked themselves into budget cutting agreements with various health care interest groups, Team Obama overestimated their ability to sell tax increases to their own caucus.

They must now choose among breaking with organized labor, dialing back their spending desires, reopening these agreements with health care providers, and budget gimmicks. Congress usually looks first to gimmicks, but the President’s unintentional elevation of the actually honest CBO Director makes that harder than usual. Anyone who thinks they have a deal should be careful. If these bills implode, all bets are off, and the probability escalates that prior promises are re-opened or ignored. (Hospitals: You’re the deep pockets. Insurers, Business and Pharma: They can make you villains again if they need to cut you more to make the budget numbers work.)

- Speed can kill:They tried to jam it through Congress quickly and failed. Their strategy was to take advantage of a huge Democratic margin in the House to pass whatever the committee chairs could agree upon, and then either cut a deal in Senate Finance, or rally their new 60-vote Senate supermajority to power through a filibuster with the August recess as a hard backstop. The strategy was predicated on the President’s tremendous popularity, first year momentum, political muscle, large partisan Congressional majorities, and speed. The goal was to rush a bill through before anyone had time to analyze it and question the policy choices within.For two months Washington has assumed that Chairman Baucus would close a back-room deal either with Senator Grassley or his own Democrats on the Finance Committee, and announce the deal the morning of the Senate Finance Committee markup to deny the economic losers time to organize opposition. This speed-based strategy presumed that partisan loyalty to a popular President would trump serious policy concerns, and it appears to have been a miscalculation. Congressional Democrats will stretch hard to help a new Democratic President succeed, but they won’t vote aye on any bill just because the White House asks them to, and certainly not when their confidence is rattled by bad employment numbers, an apparently ineffective stimulus, and for some a tough climate change vote.

If the House fails to pass the Tri-Committee bill before the August recess, I think that bill is dead. The loss of momentum would mean that the safe move for a nervous House Democrat in August would be to tell his constituents, “Don’t worry about me. I would not have voted for that bill. I will insist on changes when I go back in September.” Having heard from his constituents about their concerns, he may then return to Washington in September with a list of changes that must be made to secure his aye vote.

It would be a mistake to predict that the President will fail on health care reform. He still has enormous resources that he and his team can bring to bear. He is the most powerful and popular person in Washington. The country wants to succeed, and most of them want him to succeed. Many in the press want him to struggle, then succeed. The policy flexibility that has undermined Congressional efforts so far allows him to cut almost any deal needed to get the political victory of a signed law. He has a deep support network ready to help him sell his message to an increasingly skeptical public, and as Congress scatters for recess he will soon have the public stage to himself for a month if he so chooses. He has policy and political goodies to distribute to convince wavering Congressional allies to side with him. And he has huge partisan Congressional majorities who know their long-term political fate is tied to his. With all of this at the President’s disposal, it is amazing that his top agenda item is in such trouble.

Don’t believe anyone’s prediction about how this will turn out. What happens when Congress returns in September is for the moment unknowable.

(photo credit: whitehouse.gov)

New health insurance mandates would increase premiums

At last night’s press conference the President was exactly right when he said:

If we do not reform health care, your premiums and out-of-pocket costs will continue to skyrocket. …