A checklist for the President’s health care speech

Here is a checklist I will use this evening as I watch President Obama’s Address to a Joint Session of Congress (8 PM EDT). I hope you find it helpful.

- Deadline – Does the President set any hard process deadlines? Listen for “by Thanksgiving,” “before going home,” or “before the end of this year.” Any hard process or timing statements are critical to the outcome. Soft deadlines are important but, we have learned, non-binding.

- “Must” and its variants – There is a huge gulf between “must” and “should.” Congress will treat the first as a hard requirement and the second as friendly advice to be ignored as needed to get the votes. The brightest line is drawn by the words “I will veto.” Second is “must.” Third is “I will not sign.” In contrast, the word “should” indicates a policy preference that, if pressed, can be abandoned if that’s the only way to get a bill to the President’s desk.

- Any new numbers – I will be surprised if the President sets any new quantitative requirements on legislation. If he does, they are important.

- Public option language – This will be the most carefully scrutinized language in the speech. It’s not the most important. I assume he will say positive things about the substance of a public option, throwing a bone to House liberals who will likely vote before the Senate. The President and his advisors have repeatedly explained that they will chuck this policy overboard as needed to get a bill, and I see little upside to the President being explicit about that tonight. It is easiest if he talks about the policy rather than its place (or lack thereof) in legislation. He may use silent ambiguity about process to have it both ways for now. He will abandon it later after the House has voted, if that’s what is needed for a bill to pass the Senate.

- Does he think the problem is substance or communications? – If he talks about “clarifying” and “explaining” policies or “clearing up confusion,” then he is still stuck on the premise that he is losing the public debate in spite of the policy substance, rather than because of it. I believe good policy is good politics, and bad policy is bad politics.

- How does he characterize the opposition? – The President has characterized those who oppose this legislation as malevolent self-interested defenders of the status quo without their own reform ideas. Does he frame it this way tonight, or does he instead acknowledge that there are legitimate points of view different from his own? Sticking with demonization helps motivate his liberal base and will be the clearest signal that he has chosen a partisan tactical path. It also risks looking petty and un-Presidential.

- What did he learn from the August town halls? – Does the President acknowledge the negative feedback, or does he instead say “we had a vigorous debate in August?” Does he characterize this feedback as pushing policy in one direction, or instead as diffuse hubbub? Did the President learn anything in August about what Americans want, and is he adapting the substance of what he wants to reflect that? This matters substantively and politically. If he says “I learned from you the people,” I think he will get a positive reaction. If he says “You were misinformed,” I think many people will be insulted and angered.

- Does he explicitly reject bills developed in July to give nervous Democrats cover? – I imagine there are many Congressional Democrats who would like to tell their constituents, “We are doing something new this fall based on what we heard in August. This new bill is different from the one you hated last month.” The substantive changes made from July to September may be less important than the public framing – does the President signal that legislation now will be different than it was two months ago (as a result of learning from citizen feedback)? Doing so may relieve moderate Democrats but upset the bill’s authors and Congressional Democratic leaders, who would interpret it correctly as an admission of failure.

- Medical liability / malpractice / tort reform – POLITICO is reporting the President “plans to acknowledge a problem with malpractice litigation.” If this is accurate, does he call for it to be addressed in this legislation? This is one of the few policy changes that could fundamentally change the legislative dynamic and attract Republican interest.

- “Bend the curve” – I assume he will continue to talk about health cost growth as the underlying problem to be solved (excellent), and about the need to “bend the curve” down in the long run (also excellent). I assume he will continue to avoid proposing policies that would actually achieve this goal, and I will guess this entire topic plays a less prominent role in his speech than it did a few months ago. If he fails to mention it, that’s news.

- What is the priority: helping the insured or insuring the uninsured? – I assume he will say both are goals. Does he signal a stronger preference for one? Pollsters say the first is more important, while the farther-left Washington health policy establishment prioritizes the latter.

- “Universal” what? – The President has carefully linked the word “universal” to “health care” rather than to “health insurance” or “coverage.” “Universal health care” is an easier goal to accomplish than “universal coverage,” because those without pre-paid health insurance can use clinics and emergency care. If he uses words like “universal” or “every American” and links them to health care, it’s no change. If he links these words to “coverage” then he’s tacking further left. If he instead says “millions” or “more” and leaves out “universal” and “every,” then he is laying the groundwork to accept a radically scaled-back bill.

- Tax increases – Does he explicitly signal support for any particular tax increases? Obvious candidates include the Kerry proposal to tax health insurers for high-cost health plans, the House Democrat proposal to tax high-income people, and the new Baucus proposals to tax other medical provider sectors. If the President reiterates his proposal to raise tax rates on high-income people who itemize deductions, then pack it in. Congressional Democrats (& Republicans) killed that idea six months ago.

- Lines designed to highlight the partisan split. – Will he use specific lines designed to embarrass Republicans into standing? There will be a significant visual impact of a House Chamber clearly divided along party lines, as Congressional Democrats will stand frequently for applause lines while the Republicans remain seated. The President and his speechwriters know this, and they may try to use it to their advantage. The Machiavellian move would be to invoke Senator Kennedy’s death and link it inextricably to the need to enact the President’s desired reform this year. If Republicans stand, they look like they are supporting Kennedy-care. If they remain seated, they look like they are disrespecting the fallen Senator. If this happens, Republicans should stand. Honor the man, and disagree with his policy another day.

- Falsely claiming that opponents have no alternative. – The President did this at Monday’s AFL-CIO Labor Day Picnic. This is false. He should not repeat it.

- Straw men vs. valid substantive critiques – The President has used “death panels” and illegal immigrants claims as straw men to mischaracterize all substantive criticism as inaccurate. I think this tactic has backfired, but he may use it again tonight. Will he also respond to more valid substantive critiques? I doubt it.

- CBO says no pending bill would be deficit-neutral in the short run.

- CBO says all pending bills would increase the long-run budget deficit.

- CBO says about three million Americans would lose the employer-sponsored health insurance they have now under the House bill.

- CBO says about eight million uninsured Americans would remain uninsured and pay higher taxes under the House bill, violating the President’s pledge not to raise taxes on anyone making <$250K per year.

- An independent study says health care reform done wrong (as it is in these bills) would result in lower future wages for most American workers.

- What does his speech signal about his strategic legislative choices? My primary objective tonight will be to update my legislative scenarios based on what I hear. My pre-speech projections are unchanged from last Thursday:

- Cut a bipartisan deal on a comprehensive bill with 3 Senate Republicans, leading to a law this year; (5% chance)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the regular Senate process with 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican, leading to a law this year; (25% chance)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the reconciliation process with 50 of 59 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (25% chance)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (40% chance)

- No bill becomes law this year. (5% chance)

I will post tonight after the speech.

(photo credit: official White House flickr photostream)

Incorrect conventional wisdom about health care reform

Here are ten pieces of conventional wisdom about health care reform that I think are wrong.

CW #1. The Obama team learned and avoided the mistakes of HillaryCare.

The Obama team avoided the mistake of jamming Congress with a massive and detailed plan without consultation, and they effectively neutralized interest groups that helped kill the Health Security Act. But, like the Clinton Administration, they tried to restructure one-sixth of the economy in one big bite. This is again proving to be more than the American people are willing to swallow.

Congressional Democrats were far more effective in expanding government’s role in health care in the fifteen years after HillaryCare failed, by repeatedly enacting incremental expansions of government to the most sympathetic population slice left uncovered by a government program.

CW #2. The President needs to propose a specific detailed plan to improve his chances of success.

Congressional Democrats need Presidential guidance on a few big policy elements: public plan in or out, must a plan provide universal coverage, how should $1+ trillion of new spending be offset, how serious are you about not increasing the long-run budget deficit. Presidential leadership here means choosing whether a bill must be partisan or bipartisan, and making a few big policy choices among well-defined options.

Five Congressional committees have already marked up bills, and the sixth has specifics they have not made public. If the President were now to propose legislative language or a detailed policy spec, it would be ignored but for what it says about these first-tier policy choices. Details from the White House might have been helpful in March. Now they would be irrelevant.

CW #3. The President is ambiguous about his position on the public option.

The President and his team have clearly and repeatedly stated that the public option is not essential. In Washington terms, that means it’s out if it needs to be to get a deal. There is no ambiguity. Upcoming House floor vote notwithstanding, the public plan will be out of any final comprehensive bill unless the President chooses a 50-vote reconciliation path through the Senate. Even in that scenario it might be watered down. The marginal votes oppose the public option, so it has to drop. I expect the Administration will perpetuate the facade of ambiguity to keep the Left at bay, right up to the moment where it drops out of the bill.

CW #4. The public option is the core of the government takeover of health care.

Democratic staff drafted these bills with a belt-and-suspenders. If (when) the public option is removed from the bill, other provisions would still turn health insurance into a public utility. Even without a public option, government employees or people appointed by the government would define standard benefit packages and cost-sharing for all health insurance. The government would regulate relative premiums and redistribute premium revenues among insurers, and have authority to place limits on insurers’ profits. A government-appointed board would define guidelines for quality care and for health care delivery models. Government guidelines labeled “advisory” have a tendency to become de facto standards over time, whether or not they are legally mandated.

Even without a public option, the pending bills would make provision of health insurance largely a governmental function, although run by for-profit firms.

CW #5. This debate is mostly about health policy.

This debate is equal parts health policy and economic policy. Every bill publicly pending would increase the short-term and long-term federal budget deficit, and the Administration recently upped its 10-year deficit estimates by two thousand billion dollars. CBO says the House bill would increase long-term budget deficits by ever-increasing amounts, exacerbating the long-term entitlement spending problem under current law. The pending bills would raise taxes and result in lower wages as expanded coverage and mandated benefits increase the price of health insurance. Claims of long-term deficit reduction are unsubstantiated by any government policy analyst – even the Administration has failed to support its “bend the curve down” claims with numbers.

Policymakers should be focusing on short-term economic recovery, preventing tax increases, and reducing long-term budget deficits by slowing the growth of entitlement spending. The pending bills would instead mean higher taxes, lower wages and exploding government debt. If these bills become law, they will be the most significant change in economic policy in years. Health reform is also an economic issue.

CW #6. Governor Palin blew it by talking about �death panels� that aren�t in the bill.

Yes, Governor Palin’s “death panel” statement was an exaggeration. But as a tactical matter from the perspective of someone trying to kill the President’s health care reform, was it an unwise move?

The President spent much of August using Governor Palin’s “death panel” claim as a straw man to argue that most substantive concerns with the pending legislation were exaggerated and spurious.

Was it smart for the President to spend so much air time on the message “Don’t worry, this bill won’t kill your grandma?” That’s not exactly going on offense. He could have easily dismissed it with a single statement and then had his staff and proxies counter-attack. Instead, the President magnified the effect of Gov. Palin’s attack by repeating it.

Going after insurers, Gov. Palin, and conservative talk radio may work to fire up your political base, but it does not reassure those who have legitimate questions about the bill. If the President is talking about “death panels” while trying to sell his health reform plan, then he’s losing the battle.

In addition, I think the President’s repeated counter-attacks on outrageous straw man arguments backfired, because he failed to address the justifiable concerns expressed by millions of citizens at town halls: more government involvement in health care, bigger budget deficits, higher taxes.

CW #7. Rowdy town hall protestors hurt the opposition’s case.

Had the obnoxious shouting and disruption persisted through August, it might have backfired. Instead, it guaranteed press attention throughout the month, and magnified the impact of concerned Americans participating in democratic debate. I think the ensuing public policy debate is a good thing, and the obnoxious behavior early in August involved more people in that debate by generating news coverage.

I prefer thoughtful and impassioned yet civil debate to shouting. But democracy is sometimes impolite and raucus. A little shouting isn’t all bad if it eventually leads to impassioned debate, rather than just more shouting.

CW #8. Senators Grassley and Enzi blew up bipartisan talks among the Gang of Six and walked away from negotiations.

Democratic Senators Baucus, Conrad, and Bingaman, and Republican Senators Grassley, Enzi, and Snowe have worked for months to try to build the core of a bipartisan consensus. They have been unable to do so for three reasons:

1. The substance is difficult.

2. Each side is being pulled back by Members of their own party.

3. The President persistently undercut Chairman Baucus by denying him the ability to negotiate a final deal with Republicans.

Senators Grassley and Enzi are not fire-breathers. They are seasoned legislators who know how to cut a deal. They are also experienced enough to know they should not negotiate a deal with Chairman Baucus, only to have that deal reopened by the House and White House later in the legislative process. They want to negotiate once, not two or three times. That is reasonable and savvy.

The President and his team have known for months how to get a bipartisan deal: negotiate directly with Grassley and Enzi, or authorize Baucus to do so on their behalf. They were unwilling to do so, and are now feebly attempting to shift blame to these Republicans as they embark on a partisan legislative path.

CW #9. This policy debate is shallow and poorly-informed.

Yes, there is a lot of confusion and misinformation out there. Yes, many of the email chains are inflammatory and exaggerated (but not fishy). Yes, the press spends too many column inches and too much airtime on the political back-and-forth rather than the substance of the bills. Yes, too many people are shouting, and not enough are listening and debating. I concede that the debate is nowhere nearly as well-informed or thoughtful as it could be.

But so what? Millions of Americans are deeply involved in a discussion about a proposed fundamental change to how America works. And somehow, the real issues are seeping through the din. Even people getting distorted information from misleading emails are being subjected to a battle of ideas. Yes, those who listen only to one side of the debate will get a limited perspective. But anyone who exerts even a little effort can learn a lot, and anyone who listens only to one side but then debates someone who disagrees will learn something from that argument.

I think millions of Americans understand that this is fundamentally a debate about who should decide how much health care you get and who should have to pay for that care. I think they understand the rough consequences of an expanded government role in private health insurance and health care delivery. I think millions of them are reacting at an instinctive policy level to bigger government – higher taxes, bigger budget deficits, more government spending.

I wish millions of Americans read KeithHennessey.com and were patient enough to learn the details to be as well-informed as you, my brilliant and thoughtful readers. But I believe imperfectly-informed involvement is better than complete disengagement. And I have a core confidence that, given time, the American people are on the whole smart enough to figure out the underlying truths and make sound judgments. I am a strong believer in the inherent wisdom of the common man. I am actually pleasantly surprised how relatively well-informed this debate is, compared to so many other policy debates I have seen. I will continue to do my part to contribute to a thoughtful, impassioned, civil debate.

CW #10. The failure of comprehensive health care reform would doom an Obama presidency.

The Clinton health plan was a complete flameout, and yet President Clinton had two productive terms in office. If a comprehensive bill dies this year, I still expect a significant expansion of existing government health programs to become law, providing a significant consolation prize to a dispirited Democratic base. And I am confident that President Obama would be able to portray such a bill as a partial win, accompanied by a promise to continue fighting for larger reform. Failure to enact a comprehensive bill this year would weaken the President significantly in the short run but would not, by itself, doom his Presidency. Four years is a long time, and political weather is impossible to forecast beyond about a three-month horizon.

(photo credit: Brett Tatman)

Updating the legislative scenarios (already)

Based on yesterday’s organized leaks from the President’s staff to the press, I am updating my legislative projections one day after making them. Here are the updated projections:

<

ol>

I should clarify two points from yesterday’s post. I described these both as “paths” and “outcomes.” The President, with advice from Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid, will choose one of the first four paths. My probabilities are instead associated with these as five potential outcomes. So for example, the new White House leaks clearly suggest that the White House is steering away from (1), and probably toward (2). But my projections still allow for the possibility of outcome (1), and give (2) and (3) equal probabilities, because (a) the President may change his strategy, and (b) he can influence but not control the outcome. Please think of these as my projections of the probability distribution of possible outcomes, and not as the probability that the President will choose a particular strategic path. I hope that makes sense.

Also, path (4) encompasses two very different scenarios – one in which the Gang of Six steps in after the wheels come off and restarts the process with an incremental bill, and the other in which Democrats move a partisan incremental bill through reconciliation. I cannot at this point distinguish between the two.

I will explain the leaks, their strategic implications, what to watch, and how this has changed my projections. If you have not yet slogged through yesterday’s description of the paths, you will probably need it for this post to make sense.

Wednesday’s leaks

The President’s staff, through White House Senior Advisor David Axelrod, sent a new signal yesterday morning. The best coverage (once again) comes from Mike Allen & Jim Van De Hei at Politico.

The only thing we know for certain is that the President will address a joint session of Congress next Wednesday, September 9th. A joint session is a big deal. You can characterize this as “the President grabbing the reins to lead the country” or “the President taking a huge gamble” as you see fit. It’s probably both.

There are a lot of other things that the President’s staff are signaling, but which I assume will bounce around over the next six days:

- He will support but not insist on a public option. He is “willing to forgo” it, according to Politico. This is a reiteration of their long-standing position.

- Depending on the reporting, he may or may not “get more specific” with his prescriptions. I think this is mostly irrelevant.

- “Aides [do] not want to telegraph make-or-break demands.”

- The President’s aides (Axelrod and Gibbs) are going after Republican Gang of Six members Grassley and Enzi, accusing them of “walking away” from negotiations, and simultaneously saying nice things about Senator Snowe.

Strategic implications

It appears clear that the President’s team is giving up on Senators Grassley and Enzi, and abandoning path (1). They have shifted to blame-game mode with those two. This is not super-surprising, but it is important. It signals that the President’s team is choosing a partisan path. If he does not establish any new bright lines, then the primary (only?) purpose of the speech is to rally Democratic legislators to support him.

This initial signal suggests they’re going to try partisan path (2) rather than partisan path (3). Yesterday I wrote “I will list them in the order in which I think they will be considered” So far, so good.

I conclude they are exploring path (2) because (a) they appear to be appealing to moderates by repeating the signal that the public option can/will drop at the end of this process, and (b) they are stressing how much they like Senator Snowe. Both suggest a 60-vote strategy in the Senate.

If I’m right, then the President’s focus over the next week will be to rally Democratic legislators to unify around parameters that he specifies. While I’m sure his speech will be characterized as an Address to the Nation, his real target audience will be 255 House Democrats, 58 Senate Democrats and Senator Lieberman, and Senator Snowe.

This path works well for Senate moderates who want to vote aye on final passage on a slightly-less-left bill. I imagine members like Senators Conrad, Baucus, Lincoln, and maybe Nelson would fall into this category. Clearly they would still prefer a real bipartisan deal, but the President’s team seems to be taking that off the table.

This path is painful for liberals (House, Senate, and outside) who want a farther left bill, and for scared Democrats (many of whom are moderates) who actually want the bill to be farther left so they can comfortably vote no and protect themselves for next November. The White House advisors are signaling they intend to turn up the loyalty pressure on moderate Democrats at the same time they try to pull the substance (slightly) toward the center.

Here are the principal challenges with path (2):

- Speaker Pelosi keeps repeating that she must include a strong public option to pass a bill out of the House. This poses challenges on her left and her right:

- Liberals know that even if they vote for a strong public option in House passage, it is certain to drop from a final conference report. The White House is telegraphing that any strong public option in a House passage vote is merely a charade to provide liberal members with cover on the Left. Will that work for key House liberals?

- Blue Dogs will also know that a strong public option will drop from any final bill. If they think they will catch heat back home for voting for such a bill, then their optimal strategy is to vote no on House passage and yes for the final product (which excludes a public option).

- Combine these two factors: Can Speaker Pelosi, Leader Hoyer, and Whip Clyburn rally 218 votes for a bill which everyone knows will not be the final product? Or will they lose enough liberals who aren’t willing to play along with the charade, combined with enough Blue Dogs who don’t want to cast a meaningless pro-public option vote, that they can’t get 218 the first time around?

- In the Senate there will be no margin for error. If the President can convince Republican Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) to consider voting aye, he is at best playing with a universe of 61 votes, out of which he needs 60.

- Path (2) means they’re not using reconciliation. That has advantages and disadvantages.

- Advantages:

- No reconciliation means they don’t have to worry about the Byrd rule. No Byrd rule means they don’t have to offset the deficit increases in each year beyond 2014.

- No Byrd rule means they don’t have to worry about the “Swiss cheese problem” of losing “extraneous” provisions like the insurance mandates.

- They avoid the most effective (and valid) process abuse arguments from Republicans.

- Disadvantages:

- They need 60 of (59-61) votes consistently. With reconciliation they would need only 50 of 59. That is an enormous difference.

- They still face a 60-vote budget point of order against increasing the deficit in any of three 10-year periods beginning with 2015. This makes the offset math painful and difficult.

- The bill can be filibustered. They will need 60 votes to invoke cloture.

- The debate and votes could stretch over weeks. Is Senator Byrd healthy enough to be available over such a long timeframe?

- Non-germane amendments are in order. Senate Republicans can offer any amendment they like (health or other), and as many as they like. They can do this to try to change the bill, to cause in-cycle Democrats to have to take politically unpopular votes, or to try to fracture the potential 60-vote coalition. A pro-life amendment, for example, might garner a majority of the Senate but cause a few liberals to drop off so that Leader Reid couldn’t get 60 votes for cloture.

- Advantages:

- Each defection of a Democratic Member will significantly undermine the partisan divide I anticipate the President will try to create. In contrast, the reconciliation path expects that moderate Democrats will defect, so each one who does is not as damaging.

It is hard to hold 60 votes together with no margin for error. Really hard.

What (and whom) to watch

Things are really going to heat up in Washington. Yesterday’s signal suggests a partisan approach by the President. I imagine the August town hall intensity will translate into a partisan skirmish. Expect lots of nasty partisan rhetoric.

At the same time, the more important battles will be internal to the Democratic party. Will Democrats rally around the President, or will their internal tug-of-war continue? In theory these will be closed-door discussions, but everything will leak. The partisan fight will be intense, and Republicans can affect the debate by continuing to talk about the substance. But the vote counting is almost entirely a Democratic exercise. Is there a substantive policy that all Congressional Democrats can agree to, and can they get to that point legislatively?

In the Senate, watch Senators Rockefeller and Schumer for an indication of where liberals are. Watch in-cycle Democrats like Senators Bayh, Bennett (CO), Lincoln, and Specter. Watch wildcard Senators Nelson and Lieberman. And watch Leader Reid and Chairmen Baucus and Conrad for any comments about process. Are they all saying the same thing about not using reconciliation?

In the House, watch the Blue Dogs. After cap-and-trade, will they allow themselves to be BTUd again? Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, …

Listen closely to the argument the President and his team makes to liberals about why they are not choosing the reconciliation path that could allow for a strong public option. Are they telling liberals that path is not procedurally viable (because of deficit/Byrd rule problems), or instead that the President prefers to keep moderate Democrats onboard, and is willing to sacrifice the Left’s #1 policy priority to hold the Democratic party together? Are the President’s advisors telling liberals that the President is choosing a 60-vote strategy because he wants to, or because he has to?

Most importantly, watch the American people and whether they continue to drive the debate. Impassioned citizen participation dominated August. The White House will try to change those public views, but will also try to convince nervous Congressional Democrats to vote aye despite their angry constituents. If the August citizen passion continues to affect Members when they return to Washington, then the probability of a comprehensive bill will continue to decline.

My updated projections

- Path 1, the Gang of Six bipartisan big deal, is now highly unlikely. I have left it with a 5% probability only because this White House lacks credibility about sticking to any given strategy. If they stick with the partisan approach they are now signaling, the bipartisan big deal is dead.

- Path 2 today appears to be the White House’s chosen path. I have dramatically increased the probability of this outcome from 10% to 25%. They want to do it, but I am not sure they can do it.

- Path 3 now becomes their first fallback. I am leaving this at 25%, which should tell you I think path (2) has a fairly high likelihood of failure. It is easy to imagine them trying and failing on path (2), then tacking back to the left and using path (3). Liberals might prefer this, and may therefore dig in to make it harder for path (2) to succeed.

- Path 4, falling back to a big but incremental bill is still the most likely outcome, but I have decreased its likelihood from 50% to 40%. The President’s team increased their overall chance of success on a big bill by 10% (I think) by signaling a strategy early. Speed is their friend.

- There is still a 5% chance the wheels come off completely.

We have now entered a legislative Twilight Zone in which conditions can change on a daily basis. I won’t try to update these projections every day, but will do so occasionally.

Thanks again for reading, and for those who are leaving so many thoughtful comments.

(photo credit: teliko82)

Health Care Moves

Members of the House and Senate will return to Washington the evening of Tuesday, September 8th. Over the following several days they will compare constituent feedback on health care reform. There will be thousands of small informal discussions – Members talking to each other on the House and Senate floor during votes, in the hallway, in the gym, over lunch or coffee or drinks.

The House and Senate Democratic leaders will convene caucus meetings of all their Members to get more structured input. These leaders will meet separately and together to discuss the feedback they are receiving. Senior White House staff will be involved in most of these discussions.

At some point in those first two weeks the President, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid will need to choose a legislative path. So far the President has allowed the horses to run all over the field – at some point he needs to corral them. But all his options are now bad, and he may continue to delay choosing a path. To do so would further diminish his fading chances of legislative success.

I think much of the chaos we are seeing results from a combination of:

- Presidential indecision about which path to take and a lack of preparedness for the different paths;

- an ever-changing message from the White House;

- and a flawed set of policies and substantive arguments to which American citizens are reacting harshly.

Absent Presidential leadership on a specific policy proposal, Democrats are pulling in various directions. And I think everyone underestimated the depth and intensity of public opposition to the proposed policy changes. The August citizen town hall blowback will radically affect the closed-door Member discussions beginning next week, as will the expert polling analysis projecting large potential 2010 election losses for Democrats. A full-fledged Democratic Member panic is not out of the question.

I have written repeatedly that no one knows what will happen in September. Any analysis like this is dominated by tremendous uncertainty. I’m going to give it my best shot.

I see five possible paths for the President and Democratic Congressional leaders. I will list them in the order in which I think they will be considered, and I will assign my subjective probabilities to each.

- Cut a bipartisan deal on a comprehensive bill with 3 Senate Republicans, leading to a law this year; (10% chance)

- Pass a partisan bill through the regular Senate process with 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican, leading to a law this year; (10% chance)

- Pass a partisan bill through the reconciliation process with 50 of 59 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (25% chance)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (50% chance)

- No bill becomes law this year. (5% chance)

If you add the probabilities for 1 + 2 + 3 (in my case, 45%) you get the predicted probability of a Presidential “success,” defined as a comprehensive bill that looks somewhat like what is being publicly debated. Today I project a 55% chance of failure.

I will provide an overview of the legislative landscape, then walk through each path. What follows is highly judgmental, and I can prove none of it. It can and will change rapidly beginning seven days from now. My only defense is that over a 15-year period a President and two Senators paid me in part to do this kind of analysis. You get it for free.

Overview

A big bill is in deep trouble. The President and his team had serious problems before the August recess. Failing to pass a bill out of the House was an enormous setback. Speaker Pelosi picked up a little late momentum by cutting a deal with some Blue Dogs to get a bill out of the Energy & Commerce Committee, but at the cost of delaying final passage until the fall.

On the Senate side, bipartisan discussions among the Gang of Six (Senators Baucus, Conrad, Bingaman, Grassley, Enzi, and Snowe) were stalled. The President and Democratic Leaders needed to pick up substantial momentum in August.

Instead they lost tremendous ground, far more than anyone anticipated. More importantly, things are still rolling backward. For most Republican Members of Congress their constituent feedback makes this an easy call – they oppose the proposed bill. Many Democratic Members face conflicting pressures from their constituents, their leaders, and the President.

The Leaders’ choice of legislative path is both difficult and important. Choosing a path means picking winners and losers within the Democratic caucuses. The President’s choice can easily affect whether certain Members win re-election next November. He has postponed this decision so far. If things were going well, this would be a brilliant strategy, because he would have the flexibility in September to choose from among a few good options. Deterioration over the summer has provoked factions to dig in their heels, making all options increasingly difficult for the President. I think he now faces the question “Which path is viable,” rather than “Which path do I prefer?”

Path 1 – Cut a bipartisan deal with 3 Senate Republicans (10% chance)

This is the most straightforward of the three options. A deal among the Gang of Six would lead to a signed law. Such a deal would likely come to the Senate floor as a free-standing bill outside of the reconciliation process.

A bipartisan Gang of Six deal would obviously be more centrist than the bills now being discussed. I would expect:

- The public option would be out;

- A version of the Conrad co-op might be in, close to the original Conrad proposal;

- The (stupid) Kerry plan to tax insurers for high-cost plans might be in; and

- Other income tax increases would be out.

I would expect moderate House and Senate Democrats to support such a deal. Liberals would be upset at the loss of the public option. The White House, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid would stress to liberals that a partial win is better than nothing. This is a common refrain when you compromise on legislation.

This path looks increasingly unlikely. Senators Grassley and Enzi have been sending negative signals over the past two weeks, reaffirming the conventional July wisdom that the “Gang of Six” discussions were not moving forward.

White House Press Secretary Gibbs is laying the groundwork for Democrats to embark on a partisan path by pointing to Senator Enzi’s recent radio address as evidence that Enzi is “walking away” from negotiations. I think all Members of the Gang of Six (Baucus, Conrad, Bingaman, Grassley, Enzi, Snowe) have been negotiating in good faith since day one. I think they have been unable to get a deal for two reasons:

- There appears to be no substantive policy position that can garner a centrist super-majority of the Senate; and

- Even if there were, Chairman Baucus lacks authority to close a final deal with Republicans.

Senators Grassley and Enzi are experienced negotiators. They know that any agreement with Senators Baucus, Conrad, and Bingaman would be reopened on the Senate floor, and in conference by both House Democrats and the White House. I presume that Baucus/Conrad/Bingaman could defend the deal on the Senate floor from amendments by the Left, but they could not guarantee the outcome of conference negotiations with the House. Nobody wants to have to negotiate twice (or three times), so Grassley and Enzi need either Pelosi or the President to give Chairman Baucus their proxy to close a deal. Speaker Pelosi can’t do that, and so far the President won’t. If the Gang of Six fails, it will be because the President undercut Chairman Baucus by failing to commit to a bipartisan path.

Projection: Today this path has a 5% chance. I’m assigning it a 10% chance over time, because as other paths fail it’s possible the Gang of Six could develop a Hero Complex and try to save the day.

Path 2 – Pass a partisan bill through the regular Senate process with 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican (10% chance)

If a bipartisan deal among the Gang of Six is impossible, I expect the three Democrats (Baucus/Conrad/Bingaman) would argue for a 60-vote floor strategy outside of reconciliation. They would take a substantive position similar to what I describe under Path 1 and push Senator Reid to bring it to the floor outside of reconciliation.

I think these Senators (who are quite influential) prefer this substantive path. Senators Baucus and Conrad are also critical to Path 3 – the reconciliation path, and Senator Conrad in particular has been publicly emphasizing the procedural challenges of that path. So if you’re a “moderate” Democrat (I use the term loosely) who wants to vote aye on final passage, you would like the bill to be a centrist one.

If you’re a liberal, as are the bulk of both the House and Senate Democratic caucuses, you probably hate this path. You’re not getting any political cover from Republicans (Senator Snowe doesn’t count), and you’re sacrificing “essential” elements of the bill that you

Five people to watch in this scenario are Democratic Senators Reid, Byrd, Specter, and Nelson, and Republican Senator Snowe:

- Senator Reid needs to lead his party, but is getting hammered in Nevada and he’s in cycle. This path might give him a little cover back home. Maybe.

- You need Senator Byrd to get to 60. Is he healthy enough to vote repeatedly over the course of a week or more?

- Senator Specter’s primary challenge from the left gets stronger if he votes no on final passage. His Republican challenge in the general election gets stronger if he votes aye. How does he want to vote? As an example, if he is more concerned with the general election threat, he might prefer a partisan reconciliation path in which he can vote no, even though it’s probably not his substantive preference.

- Similarly, Senator Nelson is generally considered to be the hardest Senate Democratic vote to hold onto. Does he want a more centrist bill that he can support, or is the political heat home in Nebraska so intense that he’d rather have a leftward bill that he can oppose?

- This path works only if Senator Snowe is willing to consistently vote with Democrats. Is she? If so, she (and any moderate Democrat on the margin) has near-infinite leverage over the bill’s contents.

Watch how hard Baucus and Conrad publicly push back against Path 3.

Projection: This path happens only if (a) Senator Reid wants it for personal reasons or (b) paths 1 and 3 are impossible. 10% chance.

Path 3 – Pass a partisan bill through the reconciliation process with 50 of 59 Senate Democrats (25% chance)

This is clearly the preferred path of the Left. The Left dominates the House and Senate Democratic caucuses, and their views are closely aligned with the President’s stated policy goals (especially preferring to have a “strong” public option).

The primary problem with this path is procedural. I have written about this at length, but to summarize, there’s a two-part test:

- There are budgetary points of order that must be avoided to make sure this is still a reconciliation bill that can be passed with only 50 votes. (50 not 51 because there are now 99 Senators.) If the bill increases the deficit in any year beyond 2014, then it fails this test. In the long run, this means the offsets must be entirely cutting health spending or taxing things that grow at the same rate as health spending. Medicare and Medicaid cuts work. Taxing health benefits (good idea) or insurers (stupid but more likely) meets this test. Raising income taxes (as the House is considering) does not. If they fail this test, the entire bill loses reconciliation protection. This means it would need 60 votes to pass, and the bill would die. I think of these as “fatal” points of order.

- If Senate Democrats can avoid these fatal points of order, then they have to contend with the Byrd rule placing elements of the bill in jeopardy. This is the “Swiss cheese” problem in which major elements of a reconciliation bill could be stripped if there are not 60 votes to defend them. The “insurance reforms” and individual mandate would be in greatest jeopardy. The public plan can be drafted to survive this test.

At some point behind closed doors Senator Reid will ask Budget Chairman Conrad and Finance Chairman Baucus, “Can [a particular bill] avoid the fatal budget points of order?” If the answer is yes, then he’ll ask, “And what elements should we expect to lose to the Byrd rule?”

If the first question gets a no, then this path is not viable. If it gets a yes, then it’s viable, but at a substantive cost. It is the easiest path to conference with the House, and it leads to a more leftward bill, including a “strong” public option.

I would expect many moderate Democrats to oppose the bill if this path is chosen. This poses several challenges:

- I presume House moderates will be pulling way back in September after getting beat up in August. Will they insist that the House bill be pulled more to the center, or will they instead prefer the bill to stay left so they can vote no? Can Speaker Pelosi get 218 votes for the deal agreed to by some Blue Dogs in committee in late July? (This is a risk on any path.)

- As a procedural matter this path has a slash-and-burn feel to it. Take all the substantive arguments you heard in July and August, add to them procedural unfairness arguments, and turn up the volume a few notches. The rhetoric will get even hotter.

- Assuming at least some moderate Democrats oppose the bill on this path, there will be bipartisan opposition to this bill. That makes it harder for Democratic leaders to hold nervous members voting aye, and will undermine the partisan attacks I would anticipate from the White House and Democratic leaders.

Projection: If they can overcome the fatal points of order, this is the highest probability path of a big bill becoming law. The White House and Democratic leaders would have to bend and break arms to hold a majority in both bodies, but with sufficient White House pressure they can probably do it, barely. This is the highest probability path for a big bill only because paths 1 and 2 are so fouled up. 25% chance.

Path 3A – Two bills: one through reconciliation, one through regular order (0% chance)

Not gonna happen. It’s just too hard for the leaders to coordinate the votes across the two bills. If things were politically stable and these bills had a high probability of legislative success, then maybe you could split it up. In the current environment, it’s too unstable and too risky for the leaders to pursue. Leaders like manageable risks when they bring bills to the floor. This path creates unmanageable risks.

Projection: 0% chance

Path 4 – Fall back to a much more limited bill (50% chance)

If paths 1, 2, and 3 fail, the President and Democratic leaders will have no alternative but to fall back to a much smaller bill. It’s in this context that the Gang of Six might return to power, although a smaller bill could be implemented on a bipartisan or partisan path.

A much smaller bill would definitely exclude a public option. Some friends suggest it could include “insurance reforms” like guaranteed issue and community rating, since there appears to be bipartisan support for both. I don’t think this works for a reason I have previously explained:

- These insurance changes work only if they are combined with an enforceable individual mandate to buy health insurance.

- An enforceable individual mandate means you need subsidies to deal with the $40K earner who can’t afford to comply with the mandate.

- If you’re not going to increase the budget deficit, you need to offset the subsidies with spending cuts or tax increases.

- And you’re right back where you started, minus the public option.

You can’t make the insurance “reforms” work by themselves. In addition, insurance reforms without the individual mandate would cause insurers to awaken from their confused slumber and enter the debate with vigor (in opposition). At a late stage this could matter, especially if Democrats are trying for a bipartisan smaller bill.

For this reason, I think it’s easier to “build up” to a smaller bill. There will clearly be a bipartisan consensus to increase Medicare spending on doctors (the so-called “doc fix”). I will guess that this path leads to $100B — $200B of spending over 10 years: more Medicare money for doctors, combined with expansions of Medicaid for the poor. To offset the deficit effect, they would cut Medicare Advantage and nick at other Medicare providers, and maybe do some of the Kerry tax increase proposal. This would be an “incremental” package that advocates would argue is a small step in the right direction. I would oppose such a package, but it might be able to get 60 votes, and could almost certainly get the 50 votes needed through reconciliation, and without any significant procedural hurdles. This path could be partisan or bipartisan, and it’s way too soon to predict which.

This is what Democrats do when all else has failed, to make sure the President has something to sign. It’s a failure path that they would unconvincingly argue is a first step toward a larger reform.

This would be small compared to the big reform policy being discussed, but in any other context it would be an enormous bill. For comparison, in 2007 and 2008 President Bush sustained two vetoes over a ten-year $15 billion difference in SCHIP spending. Here we’re talking about moving $100B – $200B around as a “fallback” position.

Projection: 50% chance, because I think paths 1-3 have low probabilities of success. This probability increases by 5 percentage points each week the President delays choosing a path.

Path 5 – No bill becomes law this year (5% chance)

It’s hard to imagine how you end up here. If everything falls apart, they at least do a doc fix and throw in some “quality improvement” provisions to save face, which puts them on path 4. Still, stranger things have happened.

Projection: 5% chance.

Conclusion

Thanks for making it through this lengthy post. I hope it helps you understand the multi-dimensional nature of this decision and the interaction of what I call the 5 Ps: policy, politics, personalities, the press, and legislative process. It is complex and important.

(photo credit: dlkinney)

Who should decide whether additional medical care is worth the cost? (part 2)

Friday I took a step back from the legislative debate to look at two examples of hard choices in medical care. Unlike the examples being discussed by some elected leaders, these hard choices are ones in which one option is both medically superior and more expensive than the other. Someone then has to make a decision about whether the additional medical benefit is worth the additional cost. I believe that much of the complexity in our American health policy debate boils down to the question of who should make these cost-benefit decisions.

Today I will present your options to answer that question.

You have three options for who gets to choose whether the marginal benefit of a given medical treatment or health insurance benefit is worth the marginal cost. I think of them as “levels”:

- government;

- insurers & employers; and

- you (with advice from your doctor).

They key analytic point is that whoever controls the money makes the decision. To oversimplify, the higher you push the decision, the more you can redistribute among people. The lower you push the decision, the more efficient you are. I think that certain political realities also will affect the total amount of resources dedicated to health care, depending on at which level the decisions are made.

Equity

Let’s look at how we make similar cost-benefit decisions for other critical goods:

- food – decisions are made in level (3), with subsidies for the poor;

- housing – decisions are made in level (3), with subsidies for the poor;

- elementary and secondary education – decisions are made in level (1). It’s generally through local governments, allowing some but not complete redistribution.

- college education – decisions are made in level (3), with subsidies for all but the rich.

For most Americans under age 65, most health care resources are distributed through decisions made in level (2). Our employer negotiates with health insurers and produces a limited set of options among which we as employees can choose. Once our expenditures exceed our copayments, our insurer decides whether a particular medical treatment is worth the cost and covered by our insurance. If we disagree, we fight with our insurer.

Employer-provided health insurance creates some redistribution. The expected medical costs of a 55-year old employee are higher than those of a 25-year old employee. If each were buying health insurance as an individual, you would expect the 55-year old would face a higher premium. Most employers, however, equalize the premiums charged to their employees, allowing only for differences in single vs. family policies. By getting his health insurance through his job, the 25-year old is therefore implicitly cross-subsidizing the health insurance premium of the 55-year old. (It’s difficult to figure out whether wages adjust to account for these subsidies.)

If we push control of the money, and therefore the cost-benefit decisions, up to the government level, then there is more opportunity for policymakers to redistribute and cross-subsidize. Whether you think that’s good or bad, it is a primary argument made for moving decisions up to the government level. That redistribution could be based on income (rich >> poor) or health status (generally healthy >> predictably high cost). It could be geographic (rural >> urban) or based on gender, age, or any other criteria that Congress defines.

If we push cost-benefit decisions down to the individual, then we must keep the money at that level. This is what we do for food and housing: people buy their own food and housing with their own money. We then subsidize the poor through government programs and charity – food stamps and soup kitchens, low-income housing vouchers and shelters. To the extent we take health cost-benefit decisions out of the hands of employers and insurers and leave them in the hands of individuals and families, health insurance and health care will be distributed largely based on ability-to-pay. Those who cannot afford it will rely, as many do now, on emergency care, clinics, and charity care.

We rely on ability-to-pay to allocate most goods in our (American) society. You work and save, you earn income, you buy what you can afford with that income. This is as true for “essential” goods as for things that are clearly discretionary. We layer on top of this a progressive tax-and-transfer system that redistributes income downward.

I know of three common arguments in favor of greater redistribution for health care compared to other goods:

- There is a significantly skewed initial distribution at birth. Some of us are dealt a poor medical hand at birth and will face high medical costs throughout our lives.

- If the housing safety net fails a poor person, he has to sleep on the street. If the food safety net fails a poor person, he has to go hungry. In the extreme if the health care safety net fails a poor person, he can die.

- Since the end of World War II Americans have been largely insulated from and ignorant of the costs of the medical care that we use. This has created a cultural difference in the way we think about health care compared to other goods. We think more about the price of milk than we do about the price of an MRI.

Whatever your view on whether there should be more redistribution and cross-subsidization of health care, it is indisputable that moving health care cost-benefit decisions from insurers and employers up to government would mean more redistribution and cross-subsidization. We see examples of this in pending legislation. I imagine that the regulations to implement such a law would go further.

Efficiency

By efficiency I don’t mean “least expensive.” If we have two possible decision-makers who can decide whether the marginal cost of a particular treatment exceeds the marginal benefit, then the efficient decision-maker is the one who gets it right more often.

If you’re controlling your own money, then you know how to weigh costs. With health care the hard part is understanding the benefits. Most of us are neither medical professionals nor probability experts, so we have a difficult time understanding the actual medical benefit of a particular treatment and whether it’s worth a financial cost that we do understand. I constructed two examples in Friday’s post to highlight these kinds of choices, but I intentionally made them easy to understand, and I was precise about the medical benefits of each. In practice it’s much more difficult.

On the other hand, I argue that having someone else make that decision for you is far worse. Employers, insurers, and the government can all hire technical expertise – medical professionals who know, on average, the benefits of a particular treatment. This must then be counterbalanced with other factors that push third parties to make decisions that are less than ideal for you:

- Governments/insurers/employers have to set up rules that apply to everyone. People are different, and sometimes those rules don’t fit your particular case.

- People have different attitudes toward medical care. Third parties can’t know those preferences or account for them in their decisions.

- The cost-benefit decision depends on the cost and the resources available. Using Friday’s example 1, you might choose the Skele-Gro if it were $500, but reject it at a cost of $5,000.

- In addition to whatever resource constraint exists, third parties have other pressures on their decisions, and other incentives. A government bureaucrat has rules and laws he has to follow, deadlines, and time and workload pressures. He also faces political pressure from Congress and medical treatment interest groups (hospitals, nursing homes, doctors, nurses, drug and device manufacturers, …) These pressures make his cost-benefit decision on your behalf different from your own.

- Government bureaucracies are slow to adapt to changes in medical practices and markets.

Neither decision-making model is perfect. If most health care decisions were made by individuals, some of us would make poor decisions and screw up our own health care. Most of us would rely on medical professionals for advice, but we are all flawed beings who make mistakes.

I think that our current system of insurers and employers making these decisions for us is worse, and that moving more of these decisions up to the government level would make it even more so. I believe that more bad cost-benefit decisions would be made if those calls were made by someone in government than if you made them yourself.

Total resources

Many on the right argue that if we push these cost-benefit decisions to the government, a binding resource constraint will mean government rationing. Government will have control over the resources and will make cost-benefit decisions for us, en masse. Government will deny us care that we think we need, whether that’s through death panels or, as Megan McArdle aptly puts it, second-knee-replacement panels.

I think it’s equally likely that instead government would just blow through the resource constraint and keep spending more and more of society’s resources on health care, financed by higher taxes or even bigger budget deficits. We see this in Medicare – there’s no rationing, and the program is unaffordable. Because government has control of Medicare resources and elected officials are unwilling to impose a resource constraint, we’re on track to bankrupt our country.

I believe that moving more health care decisions, and more control over health care resources, into government hands will exacerbate this trend. I am afraid of rationing. I am just as afraid of destroying our economy even more rapidly than we are because Washington politicians promise everyone all the health care they think they want, need, and deserve, with no regard for cost.

A deceptive agreement between Left and Right

In the past few months I have twice debated on TV former Vermont Governor and DNC Chairman Howard Dean. Some viewers may have been surprised to see us both arguing against the employer-based insurance system that dominates the American health policy landscape. I believe that Governor Dean and I agree that our current health care system needs to be changed.

Don’t be deceived by this agreement, however. We agree that we dislike the status quo, but would move in opposite directions.

He argues that we should move decisions away from employers and insurers, and into government. I argue that we should move decisions away from employers and insurers, and into the hands of individuals and families (with advice from their doctors). This difference leads us to quite different policy proposals.

Pending legislation would move policy in Governor Dean’s direction. It wouldn’t go as far as a full single-payer system might, but it would move enormous amounts of money into government hands. The health care decision-making authority accompanies the money.

I think the status quo is unacceptable, but I want to move in the opposite direction – taking that money and leaving it in the hands of individuals. I would give you the authority and responsibility for making more of those difficult and painful cost-benefit decisions about health care than you have today, and far more than you would have if this legislation is enacted.

(photo credit: Shelly T.)

Who should decide whether additional medical care is worth the cost?

Let’s take a step back from the day-to-day battle on health care reform battle to focus on a core question. As I wrote earlier, I believe most of the health care debate boils down to the following:

Resources are constrained, and so someone has to make the cost-benefit decision, either by creating a rule or making decisions on a case-by-case basis. Many of those decisions are now made by insurers and employers. The House and Senate bills would move some of those decisions into the government. Changing the locus of the decision does not relax the resource constraint. It just changes who has power and control.

The value decision that underlies most of this debate flows from the question: Who should decide whether additional medical care is worth the cost?

Unfortunately, some high-level rhetoric has obscured this question.

Former Governor Sarah Palin highlighted one extreme. She created an image of government bureaucrats on “death panels”denying sick seniors life-saving and affordable treatment. By focusing on the possible denial of low-cost high-value care, it’s easy to inflame passions.

The President spent much of August rebutting this straw man. While doing so he highlighted the other extreme: when a chemically identical generic drug can be substituted for a more expensive brand name drug, one can save money without any medical downside. His “red pill – blue pill” example is less provocative but equally unconstructive. If there are cost savings with no medical difference, then it doesn’t matter who makes the decision, because the decision is a no-brainer. His reassurance is a false one.

Both leaders ducked the harder questions. Today I will illustrate the hard choices with two examples. In a follow-up post I will discuss your policy options for who should make these hard choices.

Example 1: You break your wrist (the one you write and type with). You have a doctor visit and an x-ray, which combined cost $300. There are two treatments available:

- The first is a traditional cast. Healing time = 6 weeks. Additional cost = $100.

- The second is a[n imaginary] new pain-free version of a high-tech treatment called Skele-Gro, which causes bones to heal rapidly. Healing time = 1 day, and the healed bone will be 10% stronger than one healed with a traditional cast. Additional cost = $5,000.

Is the second treatment worth the additional cost? Who should make this decision?

Who gets to decide whether 6 weeks of healed wrist and a 10% stronger result for you are worth an additional $4,900?

Example 2: A[n imaginary] new treatment for heart attacks increases the probability of survival by 1%, at an additional cost of $5 million per use.

There are a lot of heart attacks each year. Assume that if insurance covers this, your premiums will increase by $400 per year.

Who should decide whether you buy the $400 more expensive insurance that includes this treatment, or the $400 less expensive insurance that does not? Who gets to make the call about whether it’s worth a certain additional premium cost of $400 per year to increase your probability of survival, if you get a heart attack, by 1%?

I constructed example one to be medically significant but far from life-threatening or even life-altering. It’s a moderate-consequence example, and it’s about the tradeoff when you’re getting the care.

I constructed example two to illustrate a tradeoff of a small but consequential medical benefit at a high financial cost. It’s only an additional 1%, but a 1% greater chance of not dying. Then again, you only get this 1% benefit if you have a heart attack, so it might never apply to you. And since this is a decision about buying insurance, you don’t have to pay the $5 m, but only the $400 incremental cost in your insurance premium, if you want this treatment to be covered. This example is about the tradeoff when you’re buying insurance.

In both examples, one treatment is medically superior and more expensive than the other. That’s what makes these hard decisions, and better demonstrations of the true tradeoffs, than either Governor Palin’s or President Obama’s examples.

Many chafe at being confronted with these kinds of choices. They argue that, if we confront these choices, then we need to devote more resources to health care.

The problem is that there is always a resource constraint. Maybe yours is 10% or 15% higher than mine, or maybe you would redistribute funds from other people to make someone’s pie bigger. But a bigger pie does not allow you to avoid these tradeoffs. It just means you confront them at a different cost level. The question of who gets to decide is unavoidable, no matter where you fall on the policy or political spectrum.

Elected officials are particularly vulnerable to this trap. The President has fallen into it, perhaps unwittingly. No elected official wants to explain to voters that ultimately someone will have to say no to medically beneficial treatments that are expensive, so they fall back to trivial cases like the President’s chemically identical generic drug example, which ducks the tradeoff.

In my next post I will take these two examples and relate them to the pending legislative debate by focusing on the who should decide question. For now I leave you with a simple thought experiment.

- In example 1, assume that your insurance covers the cast but not the Skele-Gro. Given your financial resources, would you spend an additional $4,900 out of your own pocket for the Skele-Gro treatment? If not, how much would you be willing to pay out-of-pocket for the additional medical benefit?

- If you could design your own insurance policy, would it include the new heart attack treatment? Assume you would pay the full $300 premium increase (each year) out of your after-tax wages. If not, how much more would you be willing to pay to have this new treatment covered?

To be continued…

(photo credit: Shelly T.)

The 2010 jobs outlook

I want to continue to focus on the new economic projections from OMB and CBO. Here is some basic background:

- The unemployment rate in July was 9.4%.

- Most economists consider “full employment” to be in the 4.5% – 5.5% range.

- There are now about 154 m people in the workforce, so each tenth of a percentage point on the unemployment rate is about 150,000 people.

- This means July’s 9.4% unemployment rate translates into about 14.5 m people who want work but don’t have it.

- Rule of thumb: Because the labor force grows over time, the U.S. economy needs to create about 100K – 150K net new jobs each month for the unemployment rate to stay constant. For the unemployment rate to decline you need to exceed that range.

- The U.S. economy lost 247,000 jobs in July.

On Friday, August 7th the President spoke in the Rose Garden. He said:

Today we’re pointed in the right direction. We’re losing jobs at less than half the rate we were when I took office.

I wrote earlier about why this is the wrong way to analyze it. Now I want to compare the President’s language with his Administration’s new projections.

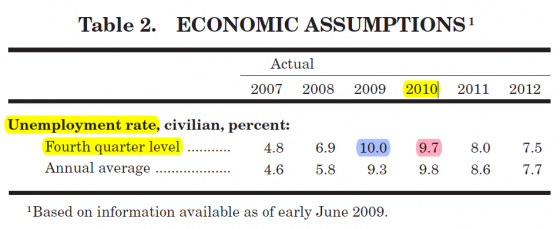

Here is an excerpt from Table 2 on page 11 of the Mid-Session Review, released Tuesday by the President’s Office of Management and Budget:

The blue highlight shows that the Administration projects the unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of this year will be 10.0%, six-tenths of a percentage point higher than it was in July.

The red highlight shows that the Administration projects the unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of next year will be 9.7%, three-tenths of a point higher than it was in July.

I draw two conclusions from this table:

- This is not “headed in the right direction.”

- If the Administration’s projection is correct, the unemployment rate will be in the high-9s during the next election and it won’t be coming down quickly.

The last point surprised me. The Administration projects the unemployment rate will decline by only three-tenths of a point from the fourth quarter of this year to the fourth quarter of next year. That’s not good.

Looking at another part of the same table, they project GDP will grow in 2010, either 2.0% or 2.9% depending on how you want to measure it. But it appears they project employment growth to be slow enough that the unemployment rate will decline very slowly throughout 2010.

The only explanation I can find to square this projection with the President’s language is footnote 1 above. Between early June and early August we had six weeks of economic data, some of which was positive. Still, I would be surprised if the Administration would rely on this new data to disclaim the forecast they published just this week.

I think the President and his team will have a tough time arguing that the stimulus is having the desired effect as long as the unemployment rate continues to climb, and even when it begins to decline if it does so slowly. The Administration will of course argue that things would be worse if they had not done the stimulus. That’s a tough message to sell when the unemployment rate is in the 9s or 10s.

I need once again to remind you that nobody really knows what next year will look like. These are all just educated guesses.

CBO does not publish projected fourth quarter levels, so we can’t compare their projections. They do project the average annual unemployment rate, and their projections are slightly more pessimistic than OMB’s. OMB projects an average annual unemployment rate next year of 9.8%. CBO projects 10.2%. The Blue Chip survey of private forecasters projects 9.9%.

There seems to be a disconnect between the President’s language, which is raising expectations that things will get better in the near future, and his Administration’s economic projections.

If these projections are realized I imagine they will affect significantly the 2010 election. If the unemployment rate is in the 9.5% – 10% range on Election Day, and if it is declining as slowly as the Administration projects, there could be a big effect in the voting booth.

(photo credit: Library of Congress)

New projection: 2.3 million fewer people working in 2010

Yesterday the Congressional Budget Office released their “summer update” publication, in which they update their baseline budget and economic projections for changes in the economy and legislation enacted so far this year. The Administration also released their “Mid-Session Review” publication, which makes similar updates for the President’s policy proposals.

Most of the press coverage focused on the updated budget deficit projections. I instead want to draw your attention to one component of the new CBO economic forecast.

We know of two big changes since CBO published their January baseline projection:

- The economy in 2009 was worse than most professional forecasters projected at the beginning of this year before President Obama took office and launched his ambitious legislative agenda. A weaker economy has caused everyone to lower their estimates of employment and their estimates of this year’s recession, where “everyone” includes CBO, OMB, and major private forecasters. Forecasters also have lowered their estimates for 2010, in part because they are starting from a lower 2009 level.

- There have been significant policy actions, the most notable of which was the $787 billion fiscal stimulus.

The new economic forecasts reflect both changes. The first makes the updated economic projections for 2009 and 2010 much worse than they were in January, and the second makes them somewhat better. (There is a vigorous debate about how much better.)

(photo credit: The White House)

There is no disagreement, however, about the net directional effect of the two. CBO and OMB project a weaker economy in the remainder of 2009 and in 2010 than they projected at the beginning of this year before enactment of the stimulus.

How much weaker?

Based on CBO’s forecast for the average unemployment rate in calendar year 2010, 2.3 million fewer people will be employed on average next year than they projected in January.

For comparison, in July there were about 140 million people employed in the U.S.

Next year’s reality will depend heavily on when the economy turns up and how quickly growth returns. A new projection of fewer people employed next year should not surprise anyone. But 2.3 million is a big bad number.

Not a blank check

Here’s the President on the Michael Smerconish radio show today:

THE PRESIDENT: The auto interventions weren’t started by me — they were started by a conservative Republican administration. The only thing that we did was rather than just write GM and Chrysler a blank check, we said, you know what, if you’re going to get any more taxpayer money, you’ve got to be accountable.

I’m going to cut-and-paste here from a post I wrote on June 7th.

Structure of the December loans to GM and Chrysler

In the last few days of December, Treasury loaned $24.9 B from TARP to GM, Chrysler, and their financing companies.

According to the terms of the loan (see pages 5-6 of the GM term sheet), by February 17th GM and Chrysler would have to submit restructuring plans to the President’s designee (and they did).

Each plan had to “achieve and sustain the long-term viability, international competitiveness and energy efficiency of the Company and its subsidiaries.” Each plan also had to “include specific actions intended” to achieve five goals. These goals came from the legislation we (the Bush team) negotiated with Rep. Frank, Rep. Pelosi, and Sen. Dodd:

- repay the loan and any other government financing;

- comply with fuel efficiency and emissions requirements and commence domestic manufacturing of advanced technology vehicles;

- achieve a positive net present value, using reasonable assumptions and taking into account all existing and projected future costs, including repayment of the Loan Amount and any other financing extended by the Government;

- rationalize costs, capitalization, and capacity with respect to the manufacturing workforce, suppliers and dealerships; and

- have a product mix and cost structure that is competitive in the U.S.

The Bush-era loans also set non-binding targets for the companies. There was no penalty if the companies developing plans missed these targets, but if they did, they had to explain why they thought they could still be viable. We took the targets from Senator Corker’s floor amendment earlier in the month:

- reduce your outstanding unsecured public debt by at least 2/3 through conversion into equity;

- reduce total compensation paid to U.S. workers so that by 12/31/09 the average per hour per person amount is competitive with workers in the transplant factories;

- eliminate the jobs bank;

- develop work rules that are competitive with the transplants by 12/31/09; and

- convert at least half of GM’s obliged payments to the VEBA to equity.

If, by March 31, the firm did not have a viability plan approved by the President’s designee, then the loan would be automatically called. Presumably the firm would then run out of cash within a few weeks and would enter a Chapter 11 process. We gave the President’s designee the authority to extend this process for 30 days.

That’s not “writ

The President repeats an important math error

In Grand Junction, Colorado last Saturday, the President repeated an arithmetic error he made earlier in the week:

Now, what I’ve proposed is going to cost roughly $900 billion — $800 billion to $900 billion. That’s a lot of money. Keep in mind it’s over 10 years. So when you hear some of these figures thrown out there, this is not per year, this is over 10 years. So let’s assume it’s about $80 billion a year. It turns out that about two-thirds of that could be paid for by eliminating waste in the existing system.