Chicago’s Olympic bid & the President’s trip

I generally stick to pure economic policy issues, but will stray a bit to discuss the 2016 Olympic bid. I am a bit of an Olympics nut, and the intersection with the Washington debate interests me.

I attended two Olympics, the Barcelona ’92 games and the Atlanta ’96 games. I worked as a volunteer at the Atlanta Games. I hope to attend many future Olympics to support American athletes.

In the Summer of 2008 I ran a small project in the White House, in which members of the White House staff sent personal letters to every member of the U.S. Olympic team in Beijing. The letters were delivered to the athletes in their residential village. It was a small gesture of support, but neat to know that each athlete representing the USA knew they had a specific person in the White House rooting for them. A few dozen durable friendships were created by this effort, and many of the US Olympians brought their families to the White House for West Wing tours given by their new staff friends.

President Bush enjoyed enormously his time at the Beijing Summer Games, as well as the athletes’ visits to the White House. One comment in particular struck me: the President said that the American athletes were universally appreciative that he attended. To them, the President was a symbol of America, not a representative of any particular political party or policy agenda. By attending the games and supporting the team, he was demonstrating that America supports her athletes in competition with other nations.

I apply the same approach to President Obama’s trip to Copenhagen in support of Chicago’s bid to host the 2016 Summer Games.

- I am glad the President went to Copenhagen to support the Chicago bid.

- Yes, it represents a signaling of Presidential priorities, and yes, national security issues and health care reform are top policy priorities. Presidents attend symbolic public events several times each week, and these events consume very little of their time. The only thing differentiating this event is the additional time and expense of traveling to Copenhagen. Hosting the Olympics is an element of soft power, and the host country generally benefits on the world stage. Chicago’s loss is therefore America’s loss.

- Federal funds do not directly support American cities when they host the Olympics. That makes sense to me. The Olympics are a private operation, and as a general matter federal taxpayers should not be funding it. If a city wants to spend their own funds, that’s a decision for their local officials and citizens.

- When an American city does host, federal funds are expended to the extent there are national and homeland security interests at stake. This seems entirely appropriate. The same is true for many “events of national significance,” like the Presidential Inaugural, the fireworks in DC on Independence Day, or the Super Bowl.

- Similarly, the taxpayer-financed cost of the President’s trip to Copenhagen doesn’t bother me. I look on this as a diplomatic trip.

- This is particularly true given that the bid city was the President’s hometown. I would have thought it odd had he not flown to Copenhagen to support Chicago.

- He took a risk by placing his personal prestige on the line. Then again, had he not traveled to Copenhagen and Chicago lost, he would be heavily second-guessed now. “If only he had attended …”

- There is a principled conservative argument that he should not have gone, based on other higher priority uses of his time. I do not subscribe to that argument, but it’s a reasonable argument to make. This is clearly one of those diplomatic judgment calls that belongs solely to the President.

- I strongly disagree with those on the right who cheer the Chicago bid loss as a diminution of a President whose policy agenda they oppose. I have strong policy disagreements with the Obama Administration, including on some international issues. But I never want him to fail when he is representing the U.S. in a diplomatic environment, even when I disagree with the policy agenda he is promoting. A weaker American President on the world stage hurts America as a nation. It’s wrong to cheer when our President is perceived as having failed overseas, and it’s counterproductive and foolish to focus too narrowly on the domestic partisan battle.

- It’s the flippin’ Olympics. Cut the guy some slack.

To those who claim that Chicago lost the bid because the rest of the world hates the U.S. because of the policies of the Bush Administration, I recommend a little deeper research into the internal politics of Olympic organizations. My conversations suggest that Chicago was instead harmed primarily by the past behavior (under prior leadership) of the U.S. Olympic Committee in its dealings with the International Olympic Committee and other National Olympic Committees. When the Olympics are held in the U.S., the global advertising revenue is much higher, and so there is a bigger revenue pie for the National Olympic Committees and the IOC to fight over. At the same time, there is an ongoing dispute about how to divide up that pie, and I understand the IOC’s denial of Chicago to be in part related to those negotiations. It looks to me like the IOC chose to award the host city to South America for the first time ever, as well as to send a signal to the USOC about their past behavior in the long-term international negotiation about Olympic advertising revenues.

There may have been payback against America in denying the Chicago bid, but as best I can tell it had much more to do with Olympic revenue-sharing and power struggles than with global diplomacy or the pitch made by President Obama.

I applaud President Obama for having traveled to Copenhagen to support Chicago’s bid.

Voting for health reform before voting against it

A couple friends have suggested a Senate legislative scenario that has significant merit, enough so that I am again updating my projections for the legislative outlook.

Last week I projected that Senator Reid would try to move legislation on the Senate floor through the regular order, probably fail at the beginning of the process, then shift to a fast-track reconciliation path, blaming Senate Republicans for forcing him to use hardball procedural tactics.

For any Senate bill, the beginning of the legislative process is the motion to proceed. Before debate and amendments begin, the Senate must agree to spend time on the bill. Under regular order, the motion to proceed is debatable. “Debatable” in effect means “can be filibustered,” and you need 60 votes to shut off a filibuster – this is called invoking cloture. This means that at least 60 Senators need to agree that the Senate should spend time on a bill for the amendment process to begin. Amendments are also debatable, and so is final passage. Each stage of the regular order process therefore requires Leader Reid to have 60 votes, including the preliminary phase before debate on the bill begins.

Based on input from these friends, I have reevaluated several assumptions I made last week. The last one is key.

- I was guessing that some Senate Democrats would be so nervous about the substance of the Baucus bill, that they might not only vote no on final passage, they might oppose invoking cloture on the motion to proceed. I now think all Senate Ds will support invoking cloture on the motion to proceed, even if some might be undecided on final Senate passage.

- There are now 60 Senate Democrats. If Leader Reid holds all of them, he does not need Senator Snowe.

- Senate Republicans might not oppose the motion to proceed.

These friends pointed out that Senate Republicans probably prefer to debate health care reform under regular order than under the reconciliation process. It’s hard to amend a reconciliation bill, and time limits bring the floor process to a conclusive end in a limited amount of time. Under regular order, it is easy to offer amendments to the bill, even if it’s hard to adopt them. And under regular order the debate and amendment process can continue forever, unless there are 60 votes to stop it. Senate Republicans trying to kill a bad health care reform bill probably have an easier time doing so under regular order, if they think they can split Senate Democrats with amendments and make moderate Democrats uncomfortable supporting the final product.

This is what happened to immigration reform. The Senate began debate and amendments, then tied itself up in knots. There was never a 60 vote coalition to support shutting off debate, and the Majority Leader eventually had to give up and pull the bill from the calendar. Technically, immigration reform was never “voted down,” because it never came to a final vote. It just died because its supporters could not find 60 votes to invoke cloture and bring the process to a definitive conclusion.

Oddly, Senate Democrats and Senate Republicans might both prefer regular order to reconciliation. Senate Democrats would avoid the expected Republican accusation of process abuse, and Senate Republicans would anticipate a higher probability of killing a bad bill by amendment and filibuster.

The same could happen with health reform, and I now believe this is the likely path the Senate will travel. I think there is a high probability that either Reid will have 60 Democrats supporting the motion to proceed, or Senate Republicans will support it, or both. I think the regular order path is more likely than I projected last week, and the reconciliation path less likely.

My updated probabilities are therefore:

- Cut a bipartisan deal on a comprehensive bill with 3 Senate Republicans, leading to a law this year; (0.1%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the regular Senate process with 60 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican, leading to a law this year; (50%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the reconciliation process with 51 of 59 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (20%)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (24.9%)

- No bill becomes law this year. (5% chance)

There is a crucial corollary that opponents of this bill need to understand. If the bill is considered under regular order, Leader Reid will probably try to encourage nervous moderate Democrats to split their votes. Leader Reid needs 60 votes to stop a filibuster, whether it’s of the motion to proceed, an amendment, or the final passage vote. Once he has invoked cloture with 60 votes and closed off debate on any one of those questions, he only needs 51 votes on the actual question. So you need 60 votes to get the vote on final passage, but only 51 votes to pass the bill.

I expect Leader Reid might say to a nervous Senate Democrat, “Stick with me on the procedural votes.” Vote with me to invoke cloture whenever I need it, so the Republicans can’t kill this with a filibuster. If you need to vote no on amendments or on final passage to please people back home, that’s fine, since I only need 51 votes there. You can split your vote.

This tactic was made famous by Senator John Kerry (D-MA) during the 2004 campaign when he said of his votes to authorize the use of force in Iraq: “I voted for it before I voted against it.” He voted aye on cloture, and no on final passage. He split his vote. Only he knows why he highlighted this during a campaign.

Watch out for Democratic Senators who are considering voting for (cloture on) the Baucus bill before voting against (final passage of) it. If your Senator votes for cloture, he or she has enabled passage of the bill, even if he or she votes no on final passage. If your Democratic Senator tells you he or she may oppose the health bill, ask if he or she will oppose cloture. The cloture votes are the ones that determine the outcome.

This tactic can be negated if it is publicly highlighted before it is used.

(photo credit: Esther)

Wall Street Journal op-ed

Mike Leavitt, Al Hubbard and I have an op-ed about health care reform in today’s Wall Street Journal.

Health “Reform” Is Income Redistribution

Let’s have an honest debate before we transfer more money from young to old.

By Michael O. Leavitt, Al Hubbard and Keith Hennessey

While many Americans are upset by ObamaCare’s $1 trillion price tag, Congress is contemplating other changes with little analysis or debate. These changes would create a massively unfair form of income redistribution and create incentives for many not to buy health insurance at all.

Let’s start with basics: Insurance protects against the risk of something bad happening. When your house is on fire you no longer need protection against risk. You need a fireman and cash to rebuild your home. But suppose the government requires insurers to sell you fire “insurance” while your house is on fire and says you can pay the same premium as people whose houses are not on fire. The result would be that few homeowners would buy insurance until their houses were on fire.

The same could happen under health insurance reform. Here’s how: President Obama proposes to require insurers to sell policies to everyone no matter what their health status. By itself this requirement, called “guaranteed issue,” would just mean that insurers would charge predictably sick people the extremely high insurance premiums that reflect their future expected costs. But if Congress adds another requirement, called “community rating,” insurers’ ability to charge higher premiums for higher risks will be sharply limited.

Thus a healthy 25-year-old and a 55-year-old with cancer would pay nearly the same premium for a health policy. Mr. Obama and his allies emphasize the benefits for the 55-year old. But the 25-year-old, who may also have a lower income, would pay significantly more than needed to cover his expected costs.

Like the homeowner who waits until his house is on fire to buy insurance, younger, poorer, healthier workers will rationally choose to avoid paying high premiums now to subsidize insurance for someone else. After all, they can always get a policy if they get sick.

To avoid this outcome, most congressional Democrats and some Republicans would combine guaranteed issue and community rating with the requirement that all workers buy health insurance—that is, an “individual mandate.” This solves the incentive problem, and guarantees that both the healthy poor 25-year-old and the sick higher-income 55-year-old have heath insurance.

But the combination of a guaranteed issue, community rating and an individual mandate means that younger, healthier, lower-income earners would be forced to subsidize older, sicker, higher-income earners. And because these subsidies are buried within health-insurance premiums, the massive income redistribution is hidden from public view and not debated.

If Congress goes down this road, health insurance premiums will increase dramatically for the overwhelming majority of people. Even if Congress mandates that everyone have health insurance, many will choose to go without and pay the tax penalty. If you think people are dissatisfied with health care now, wait until they understand that Congress voted to mandate hidden premium increases and lower wages.

There are wiser and more equitable ways to ensure that every American has access to affordable health insurance. Policy experts and state policy makers have experimented with different solutions, including high risk pools and taxpayer-funded vouchers subsidized for those who are both poor and sick. Medicaid, charity care, and uncompensated care provided by hospitals cover some of these costs today.

These solutions are imperfect, but so are the reforms being proposed in Congress. Congress should be explicit about who will pay more under its plans.

Mr. Leavitt, former secretary of Health and Human Services (2005-2009), has served as the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and a governor of Utah (1993-2003). Mr. Hubbard (2005-2007) and Mr. Hennessey (2008) served as directors of the White House National Economic Council.

(photo credit: MarkKelley)

Updated legislative scenarios for health reform

(Update: My brain was stuck in 59-Senate-Democrats mode, and was assuming that Leader Reid would need Senator Snowe’s vote to reach 60. That is now incorrect, assuming Senator Byrd is healthy enough to vote. I have edited this post accordingly.)

Here are my updated legislative projections for health reform:

- Cut a bipartisan deal on a comprehensive bill with 3 Senate Republicans, leading to a law this year; (0.1% chance, down from 5%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the regular Senate process with 60 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican, leading to a law this year; (20% chance, down from 25%)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the reconciliation process with 51 of 59 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (50% chance, up from 25%)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (24.9% chance, down from 50%)

- No bill becomes law this year. (steady at 5% chance)

I last updated my legislative scenarios more than three weeks ago, on September 3rd. Since then we have had the President’s speech, a lot of behind-the-scenes work on Congressional Democrats by the White House, and the beginning of the Senate Finance Committee markup. I think we also know at least the partial strategy of Democratic leaders. They will pursue path 2 if they can. If they can’t hold 60 votes, they will blame Republicans for failure and shift to path 3. I project a high probability of this latter scenario, higher than most experts I know.

Careful readers will see that my projected probability of success for a comprehensive bill (paths 1 + 2 + 3) has increased from 55% on September 3rd, to 70.1% today. In this respect the President’s speech, and more importantly the behind-the-scenes work he, his White House staff, and Congressional Democratic leaders have been doing, are working. I sense a much greater degree of partisan unity among Democrats, creating flexibility on policy and therefore legislative bargaining room as the leaders try to craft a bill. Congressional Democrats appear to agree that they need to agree. They are, however, still not sure about what they’re going to agree. But at least in public, they are taking much more constructive tones toward their inter-party disputes. This increases their chances of success.

Democratic Congressional leaders have chosen path 2. Leader Reid can set up the process to have a test vote at an early stage of the Senate floor procedure. (For the procedural nerds, I will guess there will be a vote on cloture on the motion to proceed to a House-passed tax bill now on the calendar, maybe the week of October 5th.) If Leader Reid gets 60 votes for that test vote, then he will know he has a high probability of succeeding on that path, and they will charge forward.

If he cannot hold 60 votes for that early test vote, either because Senator Byrd is too ill to vote (he says he is not), because Senator Snowe is not onboard, or because some of the other 59 Democratic Senators disagree on the substance, then path 2 won’t work. Leader Reid has a tactical advantage in that he will likely know this in advance of the test vote, and the vote is at the beginning of the regular order process. If he knows he will lose the key test vote, then I expect he will hold the vote, fail to get 60, blame Republicans for the failure, and immediately start down path 3, claiming that Republicans forced him to do so.

I have surveyed some experts on these probabilities. Compared to three weeks ago, all of them have increased their predictions of Democratic success on a comprehensive bill. Most, however, project a higher probability of Democratic success through path 2 rather than path 3. They are implicitly assuming that the Leaders’ chosen path will be successful, and that Leader Reid can hold 60 votes.

I am guessing there is much greater Democratic disunity than we have seen this week at the Senate Finance Committee markup. When a markup gets partisan, as it has in this case, Members tend to retreat to their respective partisan corners and it’s easier for the majority to hold all its votes. Near-unified and aggressive Republican opposition makes it slightly easier for Chairman Baucus (reinforced by Leader Reid and the White House) to whip nervous committee Democrats into line. It also increases the pressure on those who don’t like the substance (like Senator Rockefeller) not to press too hard, for fear of killing the bill entirely.

The real action is not taking place at markup. It is taking place behind closed doors, away from the markup. When the President chose a partisan path in his speech, he pushed the real debate behind closed doors. This is now a debate among House and Senate Democrats. Republicans can influence that debate only to the extent they can change the decision-making process of Democratic members, since everyone assumes that almost every Republican will vote no. If Senate Democrats can extend the consensus that is apparent at the Senate Finance Committee markup to all 60 59 members of their Caucus, and if they can get and hold Senator Snowe, then I’m wrong, my expert colleagues are right, and the Leaders’ preferred regular order path 2 will be successful.

If, however, one or more Senate Democrats looks at the substance of the committee-reported bill and says, “I cannot support that,” and if they cannot satisfy that Senator’s concerns, then Leader Reid will be forced onto path 3. There will be tremendous peer pressure on those wayward Senators to ally with the team, and if Leader Reid had 2-3 votes of wiggle room I would have an entirely different prediction. But he has to hold everybody, and that’s hard to do.

I therefore think they will try path 2, probably fail, and end up on path 3, the reconciliation path. You can see I am projecting a 71% chance that Leader Reid cannot hold his caucus and Sen. Snowe together (50% divided by 70% equals 71.4%). Senate Republicans can increase this probability if their substantive arguments against the bill are effective at making individual Senate Democrats uncomfortable.

This guess depends heavily on how Senators make their decisions. The more they care about the substance of the bill, the substantive critiques from Republicans and the press, the bill’s low popularity, and negative pressure from constituents back home, then the greater the probability that I’m right and they end up on path 3. The more they focus on the importance of sticking together as a party and supporting the President, the more likely their chosen path 2 will succeed.

When I worked for Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, I remember many closed-door meetings of the Senate Republican Leadership where the leaders had strong disagreements they could not immediately resolve. They would argue, shout, and pound the table, and remain at loggerheads. In almost all cases, as the meeting ended they would agree on a short common message to use with the press to indicate that all was well and Republicans were unified. They would do this to buy themselves time to work out their differences in private. The press, public, and their legislative opponents would see a unified partisan front which often disguised enormous intra-party struggles. It took me a while to recognize that when I saw the Democratic leaders showing a unified front to the press, they might be doing exactly the same thing.

(photo credit: rogersmj)

Understanding the Baucus health bill

Today is the third day of the Senate Finance Committee’s markup of the Baucus health bill, the “America’s Healthy Future Act of 2009.” I am going to summarize the bill in a manner similar to what I might have done for my colleagues while working in the White House.

Overview

The Baucus bill has the same basic structure as other health reform legislation being moved by the Democratic majority. This structure involves:

- “insurance reforms” including guaranteed issue and renewal and a form of community rating;

- an individual mandate to purchase insurance, enforced by a tax penalty for those who do not;

- a mandate that most employers offer their employees health insurance or pay a penalty;

- the creation of State-based insurance exchanges to restructure (“organize”) the non-employer health insurance market;

- an expansion of Medicaid; and

- subsidies for lower and middle-income people, but only for those who are not offered health insurance through their employer.

The spending increases are offset primarily by new taxes on health insurers and other industries in the health sector, penalty taxes paid by individuals and firms that do not comply with the mandates, and reduced payments to Medicare Advantage plans, drug manufacturers, and State governments.

According to CBO, about 83% of all Americans (excluding illegal aliens) have insurance now. The bill would increase that to 94%.

While the bill is the smallest of any being considered in Congress, it would still be an enormous increase in government taxation and spending. It would be the largest permanent expansion of government since the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s, and is an order of magnitude larger than anything considered in at least the past two decades. Clever drafting led to CBO scoring the bill as deficit neutral in the short run and long run. This “good” CBO score means that this bill could avoid budget points of order in the Senate, even if the fast-track reconciliation process is used. At the same time, the bill would create several political dynamics that would make massive future government spending and deficit increases virtually certain.

The bill does not contain a “public option.” It instead contains a version of Senator Conrad’s co-op proposal.

Two sentence summary: Compared to other versions of health reform, the Baucus bill is a bit smaller, fully offset with different offsets than the House bill, and without a public option. Other than that it is quite similar to the House bill.

Significant things to know about the Baucus bill

Substantively meaningless hat-tips to the left and the right

- Rather than a public option, the bill includes a version of Senator Conrad’s co-op proposal. It authorizes $6 B of loans and grants to newly formed non-profit co-ops in each State. In June I wrote about two variants of this idea. This is the less intrusive version that Sen. Conrad proposed, rather than the more harmful “public option in disguise” option floated by Senators Schumer and Rockefeller. If enacted as described by the Baucus document, these co-ops look wasteful but initially relatively harmless. There is a significant slippery slope risk that the Congress or Executive Branch would later try to apply new rules to the co-ops. There is also a short-term risk that the immediate legislative process will begin that transformation. As drafted, however, the co-op subtitle ranks low on my list of concerns.

- In a hat-tip to the generally Republican proposal to allow people to buy health insurance sold in other states, the Baucus bill would allow States to form interstate compacts to allow insurance to be sold in multiple states. This misses the point entirely: since State insurance commissioners (and State legislatures) would negotiate these compacts, they are likely to contain all the cost-increasing insurance mandates of current State law. The point of the good proposal is to take power away from State insurance commissioners, and force State regulatory authorities to compete for business the way they do for incorporation laws (Delaware won) and state banking law (South Dakota Nebraska won).

Overlooked political flashpoints

- Nobody has asked the question, “Will the Baucus bill increase or decrease health insurance premiums relative to current law?” CBO’s analysis instead blurs the question of how much health insurance will cost, with how much you will pay for your health insurance after new subsidies and taxes. I fear that these bills will increase the cost of health insurance, then shift those costs from premium payers to taxpayers. If I am right, then the Baucus bill cuts wages. If verified by CBO, that should be sufficient to kill the bill. Somebody in Congress needs to ask CBO this question.

- The combination of guaranteed issue and community rating mean the bill would dramatically lower premiums for those with predictably high health expenditures, and would dramatically increase premiums for the relatively young and healthy. When combined with an individual mandate, the Baucus bill would force younger healthier Americans to pay higher premiums to cross-subsidize older and less healthy Americans. All those 20-something staff assistants will be subsidizing their 50-something bosses.

- Assuming I’m reading this correctly, if you work for a big employer, you must take the insurance offered to you. You will not have the choice of going uninsured and paying the penalty tax. From page 29 of the Baucus mark:

Employers with 200 or more employees must automatically enroll employees into health insurance plans offered by the employer. Employees may opt out of employer coverage, however, if they are able to demonstrate that they have coverage from another source (e.g., through a public program such as Medicare, Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program or as a dependent in a spouse or other family member’s health benefits).

- The bill creates a tremendous new inequity between low- and moderate-income workers whose employers offer them health insurance, and those whose employers do not. The bill would subsidize health insurance for the second group but not for the first. This “horizontal inequity” is unsustainable and is the primary reason why in practice this bill would lead to massively higher spending and bigger deficits than projected. Jim Capretta has written about this extensively. I will do so in the near future.

Individual mandate

- President Obama told George Stephanopolous that the individual mandate is not a tax. The President was wrong, Mr. Stephanopolous was right. Page 29 of the Baucus mark says:

Excise Tax. The consequence for not maintaining insurance would be an excise tax.

The tax would not apply to everyone, though: “Exemptions from the excise tax will be made for individuals where the full premium of the lowest cost option available to them exceeds 10% of their AGI.” In addition, the mandate would not apply to those below the poverty line, in religious organizations, “experiencing hardships as determined by the Secretary of HHS,” or are Native Americans. (p. 29)

Turning the health insurance industry into a utility

- Despite having no public option, the bill in effect turns the private health insurance industry into a utility, implementing public policy goals through privately owned firms. Health insurance would be transformed from what it is today, a highly imperfect voluntary financial arrangement, into a tool of mandated redistributive social policy. The insurance premiums you pay would consist in part of payments to others deemed by policymakers to be more deserving or needy than you. I believe that the power this gives to the government officials who would design those premium rules is one of the two most dangerous elements of this bill. The other is the long-term fiscal impact on taxes and spending.

- The government would create standardized benefit packages, cost-sharing structures, and minimum actuarial values. The problem here is that the government can’t keep up with innovation, either in medical technologies, medical practices, or financing structures. Medicare is still based on an early 1960s Blue Cross insurance model, and just added a drug benefit six years ago. This new government control will crush innovation. Also, people are different. I believe we should not all be forced to fit into “bronze, silver, gold, and platinum” boxes. I would like a cheap copper box so I can have more cash for other needs.

- Like the other bills, the new insurance rules would not apply to existing (“grandfathered”) health insurance plans. This creates a bifurcated dynamic with all sorts of unintended consequences. If the new rules are so great, why should anyone choose to avoid them?

- A little-noticed element of the bill would immediately create a $5 B federal high-risk pool that is supposedly temporary. Since the new programs don’t start for several years, the uninsurable could buy “insurance” through this newly funded pot of money until 2013. In theory there would be no need for such a high-risk pool once the new all-encompassing program is started, but these things tend to have a way of morphing into permanent (spending) entities.

- The State exchanges are going to be a bureaucratic and lobbying mess. In addition to all the normal bureaucratic wrangling, every health interest group will lobby 50 State legislatures and bureaucracies to protect their (generally financial) interests. The President and his Congressional allies argue these exchanges will be neutral marketplaces. I instead anticipate ugly stories about mismanagement, greedy self-interest, intergovernmental fights at all levels, and corruption.

Medicaid & Children’s Health Insurance

- Medicaid consists of two populations: (1) kids and their parents; (2) seniors and disabled people getting subsidized long-term care. Medicaid does not today cover adults without kids. The Baucus bill would change this, making low-income childless adults eligible for Medicaid.

- Medicaid is a shared State-Federal fiscal responsibility. The Federal share varies by State from 50% to about 83% in poorer states. For the proposed Medicaid expansions the Feds would pick up a much greater share of new spending – up to 95% in some cases. This would be a significant shift in the balance of paying for health care from the States to the Feds. Baucus did this to quiet the Governors who would otherwise oppose the bill.

- The bill expands the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), requiring States to cover kids in families with incomes up to at least 250% of the poverty line. But CHIP would be transformed into a subsidy for the purchase of private health insurance sold on exchanges. I don’t like the expansion (from 200% to 250%), but do like the movement toward private insurance.

Higher taxes and spending

- The bill is scored as deficit neutral in the short-run and long-run. Kudos to the clever Baucus staff who know how to take advantage of CBO scoring conventions. The likely reality will be far worse – the bill creates several policy pressure points that will inevitably lead to much higher spending and much higher budget deficits than are scored by CBO. They have addressed their biggest procedural and rhetorical hurdles. They have not solved the underlying policy problem. Despite the CBO score, if this bill becomes law I anticipate massive deficit increases for reasons I will explain in a future post.

- In addition to massively restructuring the health sector, the Baucus bill would also be an enormous change in fiscal policy. The bill would create new entitlement spending equal to 0.7% of GDP, and growing seven percent per year for the long run. The bill would raise taxes by 1/3 of 1% of GDP in that same year. Our long-run fiscal problem is driven in part by the unsustainable growth of health entitlement spending, so the solution is to create a new unsustainable health entitlement??

Budgetary offsets

- The bill contains an aggressive version of Senator Kerry’s proposal to tax insurers that offer high-cost health plans. I am torn on this one – it’s a variant of the most important policy change that needs to be made, so I like it. But it’s a stupid and inefficient variant that will cause unintended consequences.

- The bill actually squeezes drug companies, States (through Medicaid), and Medicare Advantage plans to offset some of the spending increases. The bill purports to squeeze hospitals and other Medicare providers (but not doctors), but it doesn’t really do so. That’s a budget gimmick I will explain in a future post.

- The bill also taxes drug manufacturers, medical device manufacturers, health insurance companies and clinical labs. These are big tax increases that will be passed through to those who buy health insurance. I like using the tax code to eliminate the incentive for people to buy expensive health insurance, as is clumsily done in the Kerry provision. These tax increases, in contrast, just make insurance more expensive without any positive incentives. This is redistribution of income from those who have health insurance to those who do not.

Coming soon

Like the other bills, the Baucus bill is enormous. The conceptual language description is 223 pages. The legislative language, when drafted, will be much longer. I apologize for losing some of my usual objectivity, but I was unable to control myself. I think this legislation would be disastrous.

You can anticipate follow-up posts on a few of the most important downsides of this bill:

- an explanation of the consequences of the insurance “reforms”;

- more on the “firewall” problem and the inequity these bills would create between those who get insurance through their employer and those who do not;

- why I think this bill will lead to much bigger spending and much higher deficits than projected by CBO; and

- maybe something more on the individual mandate.

I will also soon update my legislative forecast.

If you want the primary source documents, here they are:

- Chairman Baucus’ mark and his modification. These are the primary documents being used in the Senate Finance Committee markup.

- The CBO score and Joint Tax Committee table, and the score of the modifications. The first document contains a description of the bill that is between my post above and the 223-page document.

- An explanation from Chairman Baucus’ staff of how much they think the bill “really” costs. This is their spin for internal Democratic party wrangling.

- An almost completely incomprehensible letter sent from CBO to Chairman Baucus earlier this week. This is the weakest product produced so far by CBO in this debate.

Thanks for reading.

(photo credit: Center for American Progress Action Fund)

Global climate change negotiations in color

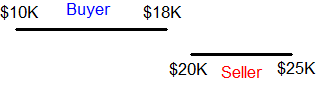

The President spoke this morning to the UN Climate Change Summit in New York City. He’s in a tough spot. In December he will send his representatives to the global climate change negotiations in Copenhagen, and the American delegation is likely to disappoint those who advocate for a global agreement pricing carbon. I don’t think the President can deliver the U.S. Senate to set a national carbon price through a carbon cap or carbon tax. Copenhagen is going to be uncomfortable for U.S. negotiators whose body language suggests they are sympathetic to the views of European Greens. I am going to start with a refresher on Negotiations 101, and then make you dizzy with some fairly complex multicolored graphs to present a model of the interests and tensions in global climate change negotiations. Imagine a buyer and seller negotiating over a used car. Each has a range of prices that make the deal worthwhile. Each party tries to keep their range secret from the other so they don’t give too much away. The buyer begins with an opening bid of $10K, the seller begins with $25K, and then they begin to approach each other’s prices. The buyer has a (secret) reservation price of $18K : that’s the most he is willing to pay for the car. The seller has a (secret) reservation price of $16K : the least he is willing to accept. Since the two reservation prices overlap there is a zone of possible agreement (ZOPA). In theory, a deal is possible. Whether they can reach agreement, and where in the ZOPA they finalize, depends on the skill of the negotiators. It is in their joint interest to agree to a deal somewhere in the ZOPA, if they can find their way to it. It’s hard because neither knows the other’s reservation price. If, however, the reservation prices do not overlap, then there is no zone of possible agreement, no matter how hard the negotiators try:

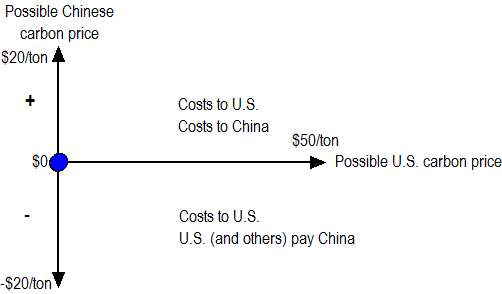

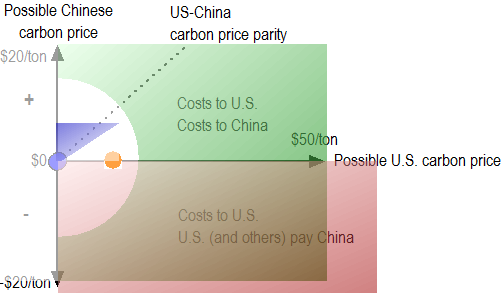

If $18K and $20K are their true reservation prices, then no deal is possible, no matter how skilled or well-intentioned are these negotiators. I think that on nationwide carbon pricing, there is no zone of possible agreement between the U.S. Senate and China. I don’t think a deal is possible, no matter what the President wants. And I think the President is not the principal U.S. party in this negotiation – he’s ultimately an agent. The disjointed U.S. Senate is the principal who must be sold on a global agreement. A positive carbon price reduces carbon emissions and imposes a cost on an economy. GDP is lower, incomes are lower. In addition, if the U.S. imposes a carbon price of $X and China imposes a price of zero, then the manufacture of carbon-intensive goods will naturally migrate from the U.S. to China. These economic costs are the primary reason why the cap-and-trade bill has been such a difficult debate in the U.S. Members of Congress have different views on how to measure and compare the economic costs and environmental benefits. The stated view of the Chinese and Indian governments is that the U.S. and Europe should set a positive carbon price, and China and India should set no carbon price. To go even further, it appears they believe that rich countries with historically high carbon emissions (like the U.S. and Western Europe) should also pay China and India to reduce their carbon emissions. I am going to use China in the following example. The same logic applies to all large developing nations, including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa. These eight nations accounted for about 38% of global CO2 emissions in 2006. On the following graph the x-axis represents a possible U.S. nationwide carbon price, and the y-axis represents a possible Chinese nationwide carbon price. Whether they’re implemented through carbon taxes, nationwide caps, or a combination of sector-based policies is unimportant for this exercise. I will hand-wave past all that to simplify a national policy into a single number, the (probably implicit) price set per ton of carbon or CO2 emitted.

We are now at the blue dot: there is no nationwide carbon-price in either the U.S. or China. (I am ignoring lots of important sectoral policies like CAFE to oversimplify.) If the U.S. imposes a nationwide carbon price, as in the House-passed bill, then the blue dot moves right. There will be costs to the U.S. economy, and U.S. emissions growth will slow. The farther right we go, the more significant are both the economic costs to the U.S., and the reductions in U.S. (and therefore global) carbon emissions. The Chinese situation is a little more complex. The Chinese are signaling they will not accept a positive carbon price that would slow their economic growth. They are instead suggesting they should be subsidized to reduce their emissions – which you can think of as a negative carbon price (oversimplifying). The red shaded area represents what the Chinese government has said they would agree to, with darker red representing “better” from what I think is the Chinese government’s perspective. They would prefer to receive bigger subsidies and for the U.S. to pay a higher carbon price, so the red gets darker as you move down and right.

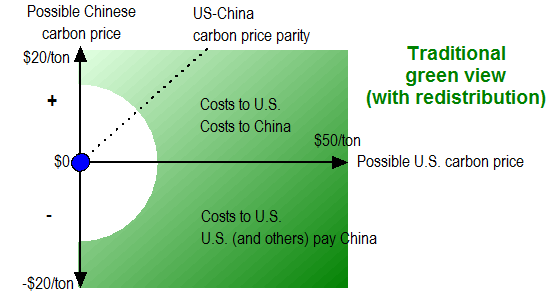

The Greens (in the U.S. and around the world) want more global emissions reductions. The farther right you move, the more the U.S. reduces its emissions. The farther up or down you move, the more China reduces its emissions – a positive carbon price in China will force them to reduce their emissions, or bigger subsidy payments from the rest of the world can encourage them to do so. The farther you move from the graph’s origin, the more total emissions are reduced and the happier a Green will be.

If you look closely you’ll see I have shaded the green so that it gets darker as you move down. In doing so I’m trying to show the alliance between climate change interests and more traditional Leftist agendas. A pure environmental policy position would value equally the top right and bottom right corners of the graph. But other left-leaning western political interests also believe that global income should be redistributed away from the U.S. and toward developing nations, including to large developing nations like China and India. The fiercest western Green advocates generally argue the U.S. should do a lot more (move right) and developing countries (including big ones like China and India) should not have to reduce their emissions, or even receive subsidies (move down). I can’t tell how much of this is a fellow-traveler policy view about the redistribution of income from rich nations to relatively poorer ones, and how much is a tactical decision by western Greens that the U.S. is more easily pressured than China. Here is my view on the marginal vote is in the U.S. Senate, shaded in blue below.

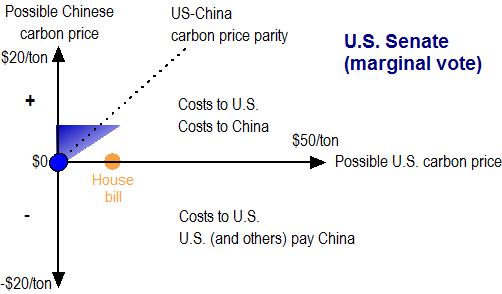

I think the American people, and enough of their Senators to matter, would reject areas below the x-axis. If disguised properly as broad-based multilateral aid, the Administration and its allies may be able to squeeze a few billion dollars out of American taxpayers for climate change subsidies to the developing world. At the same time, I think it is impossible that the marginal Senate vote would agree to use taxpayer funds to directly subsidize China to reduce its carbon emissions. Similarly, the Senate might in theory agree to move right and agree to a nationwide carbon price, but only if:

- it’s not too big of a price (thus, not too far right) because of the economic costs imposed on the U.S.; and

- it does not create too big of a competitive disadvantage for American firms relative to their Chinese and Indian counterparts.

This second point is captured in the dotted line, which represents equal carbon prices in the U.S. and China. It’s easy to imagine a Member saying “I’ll vote for a reasonable (read: small) carbon price in the U.S., so long as it doesn’t disadvantage U.S. firms relative to Chinese and Indian competitors.” I’ve allowed a little room to the right of the dotted line to show that Congress might be willing to slightly “disadvantage U.S. firms, insisting on “parity” rather than “equality.” The orange dot represents the House-passed bill. It would set a positive carbon price for the U.S., but more than I think the marginal U.S. Senate vote is willing to support. OK, now put on your 3D glasses. Let’s overlay the Chinese government position (stated), the traditional Green view, and the marginal U.S. Senate vote. Is there any area where all three overlap, any Zone of Possible Agreement among all three parties?

Nope, no Zone of Possible Agreement. In particular, the only places where the marginal U.S. Senate vote and the Chinese government positions (blue and red) overlap is the origin point (where we are now) and a very small segment of the x-axis, representing a tiny U.S. carbon price. Even that looks unlikely, and the Greens (who have significant advocates on the left of the Senate Democratic caucus) find it unacceptable. The Greens (especially in Western Europe) and China can agree on an area far to the right and at or below the x-axis, in which the U.S. imposes a significant domestic carbon price and the Chinese and Indians impose no price or even get subsidized. The Senate (and American voters, I think) will never go there. We saw this in the late 90’s when the Senate unanimously rejected the Kyoto agreement. Interestingly, there’s an area where the Greens and the U.S. could team up, along the dotted line that slopes upward and to the right. The Greens would have to moderate their expectations, shrinking the white semicircle a bit until it overlaps the blue.Such an alliance would then try to pressure large developing nations to “do their part.” President Obama used language like this today at the UN Conference:

But those rapidly growing developing nations that will produce nearly all the growth in global carbon emissions in the decades ahead must do their part, as well. Some of these nations have already made great strides with the development and deployment of clean energy. Still, they need to commit to strong measures at home and agree to stand behind those commitments just as the developed nations must stand behind their own. We cannot meet this challenge unless all the largest emitters of greenhouse gas pollution act together. There’s no other way.

A final warning: the above analysis cuts to the core issue of setting a national carbon price to illustrate the fundamental negotiating interests and tensions. Yes, there are areas for productive incremental cooperation. My favorite of these is the push for all nations to repeal tariff and non-tariff barriers to clean energy and carbon-reducing technologies, most effectively advocated by my former colleague Dan Price. Whatever incremental agreements are made, the above tension will remain, and it shows why I think a negotiated global carbon price is highly unlikely and the President is in a tough spot.

20 questions for the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission

Here are twenty questions I hope we can answer on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC). As I said this morning in my opening statement at the commission’s first meeting, if the commission could answer these questions, I think we would significantly advance the understanding of what happened and help policymakers address the root causes of the financial and economic crisis.

I do not intend this list to be comprehensive, nor does it cover every policy area that was important to the crisis. For instance, it ignores the role of credit rating agencies, which were responsible for key information failures. This list instead focuses on what I think are the most important and difficult unresolved questions about which there is significant debate. Answers to these questions could be fit into a larger explanation of what happened.

I have preliminary views on answers to many of these questions, and perceptive readers may be able to infer my lean from some of the phrasing. I have tried to tone that down as much as possible and present these as questions that are open for legitimate debate. I hope you and my fellow commissioners find them useful. I also hope that I can develop better answers during my work on the commission.

Here then are 20 important questions about the financial and economic crisis. (Technically this is better labeled “20 topics,” since several items contain multiple sub-questions.) I invite comments, suggested additional questions (ideally framed in the same relatively open manner), and suggested answers. Please assume any input you provide is principally for my use. Commission Chairman Angelides said today his goal is to have a website and method for providing formal input to the entire commission established by the end of this month.

Credit bubble

- What were the relative contributions to a credit bubble in the U.S. of (a) changes in global savings; (b) changes in relative savings between the U.S. and other (especially developing) countries; and (c) low interest-rate policies of the Greenspan Fed? Was risk systematically underpriced in the US and other countries?

Housing finance

- To what extent did well-intentioned policies designed to encourage the expansion of homeownership contribute to a relaxation of lending standards and people buying houses they could not and would never be able to afford? If so, which specific policies contributed to this problem?

- Were housing finance problems a cause of the crisis, the primary cause of the crisis, or primarily the trigger that set off other problems?

Financial institutions (broad policy questions)

- Was this a problem of financial institutions or financial markets? To the extent that markets collapsed (like certain securitization markets), did the market mechanisms fail, or instead did the funding sources just dry up?

- What definitions of “too big and interconnected to fail suddenly” did policymakers and regulators use, and how did those change over time? What’s the best way to define this test, and should it be set in advance by rule or left as a judgment call based on the specific situation?

- Did the capital purchase program of TARP work? Was it the right decision to use taxpayer funds to provide public capital to the largest financial institutions to prevent systemic failure? In retrospect, was the decision to use TARP resources for direct equity investment rather than to buy troubled assets a wise one? Was $700 B a reasonable number given the circumstances?

- Why did the stress tests work? Was it because investors had a common set of benchmarks, or because market participants perceived a bank’s inclusion in the stress test as an indication that it was too big to fail? Did the stress tests create a new implied government guarantee around 19 of the largest U.S. financial institutions?

- The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act allowed companies to merge commercial and investment banking activities. Did this contribute to extremely high leverage levels and place the financial system at risk? The removal of that same firewall also allowed the Fed to quickly approve Goldman Sachs’ and Morgan Stanley’s conversions into Bank Holding Companies, providing them protection during the height of the crisis. Was removal of the firewall net good or bad?

Failures and near-failures of particular financial institutions

- To what extent did three aspects of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: (a) their policy-induced dominant position in mortgage securitization; (b) their large retained portfolios of mortgage-based assets and (c) their regulatory treatment as equivalent to US government debt; cause or contribute to three resultant failures: (i) the insolvency of Fannie and Freddie; (ii) the lowering of credit standards for mortgages; and (iii) the failure or anticipated failure of other financial institutions?

- Was there a legally and economically viable option available to save Lehman? If so, based on what we know now, should Lehman have been saved?

- Did the intersection of mark-to-market accounting and relatively inflexible capital standards substantially contribute to the demise of any particular financial institution?

- In September and October 2008, leaders of several large financial institutions told the Administration that “the shorts” were trying to cause their apparently healthy institutions to fail. These leaders argued the SEC should reinstate the uptick rule to make this behavior more difficult. Were the shorts trying to bring down these institutions? If so, was their behavior illegal or inappropriate? And did the SEC’s reinstatement of the rule have any impact?

The regulators

- Several heavily regulated large financial institutions failed both because they were highly leveraged and because they made bad bets. Did regulatory examiners miss both elements? If they didn’t miss them, why did regulators allow these institutions to place themselves and the financial system at so much risk?

- To what extent did banking regulators’ reliance on the banks to monitor their own operations and activities contribute to the crisis?

- Was there specific real-time information that policymakers or regulators lacked about (a) hedge funds; (b) credit default swaps; or (c) other unregulated financial institutions and “dark markets” that would have been helpful in identifying particular problems before they occurred or changed policy reactions during the crisis?

Metrics

- How did different definitions of Tier I capital contribute to the crisis? Did different parts of the financial system with more stringent definitions perform better?

- Is there an economically best summary measure of a financial institution’s leverage? How did that metric compare for the largest financial institutions in mid-2008 to historic norms? How did it compare to other countries?

Executive compensation

- How does one define “excessive risk-taking,” and what specific compensation structures contributed to it? Did these compensation structures cause problems across-the-board, or only in firms with other problems?

Where are we now, and where should we be?

- Other than the absence of one large investment bank, how are the financial system and incentives and behavior in large financial institutions today different from September 1, 2008? (h/t James Aitken)

- Should policymakers try to restore the levels and types of lending and funding flows that existed 13 months ago, or is there a lower and different “new normal”?

(photo credit: Oberazzi)

My opening statement at today’s Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission meeting

Here is the opening statement I gave at the first public meeting of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, held this morning in a hearing room in the House Longworth Office Building.

<

blockquote>Thank you Mr. Chairman. First I’d like to thank Senator McConnell for appointing me to this commission. I would also like to thank you and Vice Chairman Thomas for your work getting us started, and Mr. Greene for agreeing to contribute his expertise and experience.

I think and hope that I bring a somewhat unique perspective to our work. I looked at an old calendar, and one year and one day ago I hosted the Roosevelt Room briefing for President Bush at which Secretary Paulson and Chairman Bernanke presented their recommendation to intervene to prevent AIG from failing suddenly. 364 days ago I hosted the decisional meeting at which President Bush accepted the Paulson-Bernanke recommendation to propose the TARP, and the following night I ran the staff conference call until 1 AM where we drafted the famous three pages of legislative language for the TARP. I coordinated the policy process for President Bush that led to the loans go GM and Chrysler in late December of last year. Throughout 2008 and 2009, and for several years before that, I served on President Bush’s National Economic Council staff working on issues including financial regulatory and housing policy. I hope to share some of my insider’s view, and I hope to help the commission and the public understand how the options looked to policymakers who were dealing with the crisis in real time, operating with imperfect information and severe constraints. Our task is now one of hindsight, where we know what happened. It’s critical to remember that the past is known, but the future is uncertain.

I think what we’re doing here is very important. We also need to make sure it’s relevant. We have a reporting deadline of 15 months from now. If we wait that long to produce any usable information, then the work of this commission will be far less relevant to the policymaking process. The Administration and Congress say that want to move legislation this fall addressing certain causes of the financial crisis. I doubt they will succeed in doing so. At the same time, I think it’s essential that we contribute whatever useful information and analysis we can to those policymaking debates before they finish.

I surmise that most people in positions of power are not particularly excited that this commission exists. The Administration has already offered its policy proposals, and the President did not call for the creation of this commission. The Congressional committee chairs say they want to move legislation this Fall, and the regulatory agencies are beginning their bureaucratic jockeying for position. Many of the affected constituencies in the financial sector are thinking about how to play defense against the work that we do. Other than the Members of Congress who created this panel and a couple hundred million Americans who are justifiably furious with what happened last year in Washington and Wall Street, I’m not sure who wants us to succeed.

I believe the solution is for us to move quickly and aggressively, and I urge you and the chairman to develop a mechanism for the commission to produce useful information to the public and policymakers over the course of the next year and a quarter. If we hold all of our information until next December, our work will be irrelevant.

There is a temptation in this kind of process to look for villains, and indeed some have already been found and locked up. I expect we will uncover more. In Washington the easiest solution is to form an unruly political mob and march on Wall Street, and we have seen some of that behavior over the past year. I believe that part of our job is to help Washington policymakers also look in the mirror and realize that there are systemic pressures that created or exacerbated these problems, whether they are the iron triangles of particular financial interests working to weaken their oversight and regulation, or various subsectors using legislation as a competitive battleground, or the overwhelming bipartisan desire to do ever more to encourage homeownership, without regard for the adverse consequences of their actions. I strongly believe that politically popular laws enacted by Congress greatly contributed to the crisis, and I think it is essential we understand those causes.

Even having been on the inside throughout the crisis, I have a lot of unanswered questions. I have built a list of 20 questions that I think are important to answer, inspired by the list of topics directed by Congress. I won’t read all 20 questions here today, but I do want to highlight a few. I will provide my fellow commissioners with the full list of 20 questions, and will also post them this afternoon on my blog at KeithHennessey.com.

Here, then, are six of those twenty topics. If we as a commission could answer these questions, I think we could significantly advance the understanding of what happened, and help policymakers address the root causes.

- What were the relative contributions to a credit bubble in the U.S. of (a) changes in global savings; (b) changes in relative savings between the U.S. and other (especially developing) countries; and (c) low interest-rate policies of the Greenspan Fed?

- To what extent did well-intentioned policies designed to encourage the expansion of homeownership contribute to a relaxation of lending standards and people buying houses they could not and would never be able to afford?

- Did the capital purchase program of TARP work? Was it the right decision to use taxpayer funds to provide public capital to the largest financial institutions to prevent systemic failure? In retrospect, was the decision to use TARP resources for direct equity investment rather than to buy troubled assets a wise one? Was $700 B a reasonable number given the circumstances?

- Was there a legally and economically viable option available to save Lehman? If so, based on what we know now, should Lehman have been saved?

- I think that several heavily regulated large financial institutions failed both because they were highly leveraged and because they made bad bets. Did regulatory examiners miss both elements? If they didn’t miss them, why did regulators allow these institutions to place themselves and the financial system at so much risk?

- To what extent did three aspects of Fannie/Freddie: (a) their dominant position in mortgage securitization; (b) their large retained portfolios of mortgage-based assets and (c) their legal treatment as equivalent to US government debt; cause or contribute to three resultant failures: (i) the insolvency of Fannie and Freddie; (ii) the lowering of credit standards for mortgages; (iii) the failure or anticipated failure of other financial institutions?

If anyone in the public is interested in the other questions, you can find them later today on the web at KeithHennessey.com.

I want to hit three process points before concluding:

- I want to thank the Chairman and Vice Chairman for including whistleblower protections. I will work with Mr. Greene on the details to make sure we can get the information we need.

- I know there’s been some discussion about whether we should produce recommendations. I am in favor of doing so.

- I would like to offer a concrete suggestion: let’s build a timeline, what is sometimes called a “tick-tock.” I have a big picture timeline that we used in the Administration that I will contribute to get us started, and I know the NY Fed has built a couple of excellent timelines.

Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I look forward to working with you and the other members of the commission.

(photo credit: KeithBurtis)

Reviewing the checklist from the President’s speech

Let’s compare my checklist with what the President said tonight.

- Deadline – No deadline. Update: AP reports VP Biden as saying, “I believe we will have a bill before Thanksgiving.” That’s a prediction but not a deadline.

- “Must” and its variants – I found one bright line, and one fuzzy line claiming to be bright:

- “But I will not back down on the basic principle that if Americans can’t find affordable coverage, we will provide you with a choice.”

- “I will not sign a plan that adds one dime to our deficits – either now or in the future. Period. And to prove that I’m serious, there will be a provision in this plan that requires us to come forward with more spending cuts if the savings we promised don’t materialize.”

- Any new numbers – The President surprised me by proposing a specific number for “his plan”: “around $900 billion over ten years.” While this is less than the $1+ trillion in the House bills, it’s still an enormous amount of money.

- Public option language – He spent the bulk of this part of the speech explaining why he favors a public option. But he was weaker in support of the public option than I anticipated, and he talked more about legislative packaging than I anticipated:

- “But an additional step we can take …” (Rather than “we should take” or “we must take”)

- “But its impact shouldn’t be exaggerated – by the left, the right, or the media. It is only one part of my plan, and should not be used as a handy excuse for the usual Washington ideological battles.”

- “The public option is only a means to that end … and we should remain open to other ideas that accomplish our ultimate goal.”

- And then he explicitly references Senator Snowe’s trigger idea and Senator Conrad’s co-op idea as “constructive ideas worth exploring.”

- Does he think the problem is substance or communications? – Communications: “Instead of honest debate, we have seen scare tactics.”

- How does he characterize the opposition? – He went after them hard. He called out “radio and cable talk show hosts,” “prominent politicians” (I assume he means Gov. Palin), and “special interests.”

- What did he learn from the August town halls? – Apparently nothing? He never referenced the August town halls. This surprised me.

- Does he explicitly reject bills developed in July to give nervous Democrats cover? – No.

- Medical liability / malpractice / tort reform – He committed to begin medial liability demonstration projects through administrative action. I assume he believes this obviates the need for the subject to be addressed in legislation.

- What is the priority: helping the insured or insuring the uninsured? – Both, as expected. He puts the insured first, but doesn’t strongly prioritize one over the other.

- “Universal” what? – OK, this one is fascinating. Nowhere in the speech does he promise universal health insurance, or universal health care. His only specific universal statement is “It’s time to give every American the same opportunity [to buy health insurance through an exchange] that we’ve given ourselves.” This is a fallback, allowing him to declare victory if expanded coverage falls far short of universality. You have to look carefully to see this. (I had to word search for “universal” and “every.”)

- Tax increases – He proposes the Kerry policy: “This reform will charge insurance companies a fee for their most expensive policies, which will encourage them to provide greater value for the money – an idea which has the support of Democratic and Republican experts.” This is inaccurate. D and R experts have endorsed repealing or capping the current-law tax exclusion for individuals who buy expensive employer-sponsored insurance plans. Experts on both sides of the aisle have criticized the Kerry variant as inefficient and silly/stupid.

- Lines designed to highlight the partisan split. – He made the Kennedy linkage. To my ear the speech sounded extremely partisan.

- Falsely claiming that opponents have no alternative. – As best I can tell, he avoided the direct accusation.

- Straw men vs. valid substantive critiques – He again highlighted the straw men. He tried to address the deficit point. I’ll address this more tomorrow.

- What does his speech signal about his strategic legislative choices? – I’m not changing my projections this evening, but expect I will update them before the weekend. I need to see at least a day of public and Member reaction.

- Cut a bipartisan deal on a comprehensive bill with 3 Senate Republicans, leading to a law this year; (5% chance)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the regular Senate process with 59 Senate Democrats + one Republican, leading to a law this year; (25% chance)

- Pass a partisan comprehensive bill through the reconciliation process with 50 of 59 Senate Democrats, leading to a law this year; (25% chance)

- Fall back to a much more limited bill that becomes law this year; (40% chance)

- No bill becomes law this year. (5% chance)

The deficit language is the most interesting. He tries to be definitive:

I will not sign a plan that adds one dime to our deficits – either now or in the future. Period.

He immediately follows this with language that is written as if it strengthens this commitment. I think instead it undermines the commitment.

And to prove that I’m serious, there will be a provision in this plan that requires us to come forward with more spending cuts if the savings we promised don’t materialize.

I think he’s anticipating that the Congressional Budget Office will continue to score legislation as increasing long-term budget deficits by an increasing amount each year. The President and his Budget Director will, I think, continue to assert that their “game changers” will reduce long-term budget deficits, despite providing no quantitative evidence to support this claim. This new Presidential language suggests that they will include additional language that requires actual spending cuts if (when) the game changers don’t work.

If I’m right, it’s a transparent gimmick designed to try to get CBO to say the bills don’t increase the long-term budget deficit, without actually making any of the hard choices needed to do so. If you care about the deficit, keep a close eye on this element of the President’s proposal. I will help you do so.

Finally, the President characterized his proposal as a “new plan.” We’ll see if he backs that plan up with anything more on paper.

(photo credit: Joe Plocki)

The text of the President’s health care speech

Remarks of President Barack Obama – As Prepared for Delivery

Address to a Joint Session of Congress on Health Care

Wednesday, September 9th, 2009

Washington, DC

Madame Speaker, Vice President Biden, Members of Congress, and the American people:

When I spoke here last winter, this nation was facing the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. We were losing an average of 700,000 jobs per month. Credit was frozen. And our financial system was on the verge of collapse.

As any American who is still looking for work or a way to pay their bills will tell you, we are by no means out of the woods. A full and vibrant recovery is many months away. And I will not let up until those Americans who seek jobs can find them; until those businesses that seek capital and credit can thrive; until all responsible homeowners can stay in their homes. That is our ultimate goal. But thanks to the bold and decisive action we have taken since January, I can stand here with confidence and say that we have pulled this economy back from the brink.

I want to thank the members of this body for your efforts and your support in these last several months, and especially those who have taken the difficult votes that have put us on a path to recovery. I also want to thank the American people for their patience and resolve during this trying time for our nation.

But we did not come here just to clean up crises. We came to build a future. So tonight, I return to speak to all of you about an issue that is central to that future – and that is the issue of health care.

I am not the first President to take up this cause, but I am determined to be the last. It has now been nearly a century since Theodore Roosevelt first called for health care reform. And ever since, nearly every President and Congress, whether Democrat or Republican, has attempted to meet this challenge in some way. A bill for comprehensive health reform was first introduced by John Dingell Sr. in 1943. Sixty-five years later, his son continues to introduce that same bill at the beginning of each session.

Our collective failure to meet this challenge – year after year, decade after decade – has led us to a breaking point. Everyone understands the extraordinary hardships that are placed on the uninsured, who live every day just one accident or illness away from bankruptcy. These are not primarily people on welfare. These are middle-class Americans. Some can’t get insurance on the job. Others are self-employed, and can’t afford it, since buying insurance on your own costs you three times as much as the coverage you get from your employer. Many other Americans who are willing and able to pay are still denied insurance due to previous illnesses or conditions that insurance companies decide are too risky or expensive to cover.

We are the only advanced democracy on Earth – the only wealthy nation – that allows such hardships for millions of its people. There are now more than thirty million American citizens who cannot get coverage. In just a two year period, one in every three Americans goes without health care coverage at some point. And every day, 14,000 Americans lose their coverage. In other words, it can happen to anyone.

But the problem that plagues the health care system is not just a problem of the uninsured. Those who do have insurance have never had less security and stability than they do today. More and more Americans worry that if you move, lose your job, or change your job, you’ll lose your health insurance too. More and more Americans pay their premiums, only to discover that their insurance company has dropped their coverage when they get sick, or won’t pay the full cost of care. It happens every day.

One man from Illinois lost his coverage in the middle of chemotherapy because his insurer found that he hadn’t reported gallstones that he didn’t even know about. They delayed his treatment, and he died because of it. Another woman from Texas was about to get a double mastectomy when her insurance company canceled her policy because she forgot to declare a case of acne. By the time she had her insurance reinstated, her breast cancer more than doubled in size. That is heart-breaking, it is wrong, and no one should be treated that way in the United States of America.

Then there’s the problem of rising costs. We spend one-and-a-half times more per person on health care than any other country, but we aren’t any healthier for it. This is one of the reasons that insurance premiums have gone up three times faster than wages. It’s why so many employers – especially small businesses – are forcing their employees to pay more for insurance, or are dropping their coverage entirely. It’s why so many aspiring entrepreneurs cannot afford to open a business in the first place, and why American businesses that compete internationally – like our automakers – are at a huge disadvantage. And it’s why those of us with health insurance are also paying a hidden and growing tax for those without it – about $1000 per year that pays for somebody else’s emergency room and charitable care.

Finally, our health care system is placing an unsustainable burden on taxpayers. When health care costs grow at the rate they have, it puts greater pressure on programs like Medicare and Medicaid. If we do nothing to slow these skyrocketing costs, we will eventually be spending more on Medicare and Medicaid than every other government program combined. Put simply, our health care problem is our deficit problem. Nothing else even comes close.

These are the facts. Nobody disputes them. We know we must reform this system. The question is how.

There are those on the left who believe that the only way to fix the system is through a single-payer system like Canada’s, where we would severely restrict the private insurance market and have the government provide coverage for everyone. On the right, there are those who argue that we should end the employer-based system and leave individuals to buy health insurance on their own.

I have to say that there are arguments to be made for both approaches. But either one would represent a radical shift that would disrupt the health care most people currently have. Since health care represents one-sixth of our economy, I believe it makes more sense to build on what works and fix what doesn’t, rather than try to build an entirely new system from scratch. And that is precisely what those of you in Congress have tried to do over the past several months.

During that time, we have seen Washington at its best and its worst.

We have seen many in this chamber work tirelessly for the better part of this year to offer thoughtful ideas about how to achieve reform. Of the five committees asked to develop bills, four have completed their work, and the Senate Finance Committee announced today that it will move forward next week. That has never happened before. Our overall efforts have been supported by an unprecedented coalition of doctors and nurses; hospitals, seniors’ groups and even drug companies – many of whom opposed reform in the past. And there is agreement in this chamber on about eighty percent of what needs to be done, putting us closer to the goal of reform than we have ever been.