Dr. Gruber’s honesty about lying

MIT Economist Dr. Jonathan Gruber, widely cited as “the architect of ObamaCare,” recently committed a Kinsley gaffe, “when a politician tells the truth – some obvious truth he isn’t supposed to say.”

This bill was written in a tortured way to make sure CBO did not score the mandate as taxes. If CBO scored the mandate as taxes, the bill dies. Okay, so it’s written to do that. In terms of risk rated subsidies, if you had a law which said that healthy people are going to pay in – you made explicit healthy people pay in and sick people get money, it would not have passed… Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage. And basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter or whatever, but basically that was really really critical for the thing to pass. It’s a second-best argument. Look, I wish Mark was right that we could make it all transparent, but I’d rather have this law than not.

This provokes four questions:

- Is Dr. Gruber right that lack of transparency was a huge political advantage in enacting ObamaCare?

- Do Dr. Gruber’s allies in Congress and the Obama White House agree that ObamaCare cross-subsidies were intentionally obscured to avoid politically unpopular votes?

- Do they agree with the more general principle, that some large, explicit, and transparent subsidies will be unpopular, and that the only way to enact them is to hide and obscure them?

- If so, is it ethical to hide and obscure large cross-subsidies (or large costs), in ObamaCare and elsewhere, so they can be enacted into law? Does the end of greater redistribution justify the means of obfuscation, of lying to voters?

Here are my answers.

- Yes. Dr. Gruber is right that lack of transparency provided a huge political advantage in enacting ObamaCare. He is correct that the cross-subsidies within that bill would have doomed it had they been explicit, transparent, and well understood. If your goal is to enact unpopular subsidies then hiding them is an effective means to doing so.

- Yes. I would bet heavily that both Team Obama and key Congressional Democrats involved in enacting the Affordable Care Act intentionally obscured these policies as Dr. Gruber described and for the reasons he gave. I think this logic permeates the construction, drafting, and enactment of this law.

- Yes. I think this tactic is core to progressives’ long-term success in expanding government’s function as a massive income redistribution machine. This logic underlies hidden cross-subsidies in many of our largest government programs and the taxes imposed to finance them. It is on occasion embraced across the political spectrum, but it’s a tool used far more often by the Left to redistribute society’s resources behind our backs.

- No. I think this tactic is repulsive and unethical in a representative democracy.

Here are a few areas where American economic policy hides or obscures subsidies or costs, I believe intentionally.

- As Dr. Gruber points out, in ObamaCare the healthy cross-subsidize the sick. He does not point out that embedded within this the healthy subsidize the sick for the portion of their sickness related to unhealthy behaviors. A Congressional floor vote to defend such a value choice, if made transparent and explicit, would certainly fail.

- ObamaCare also forces young people to subsidize older people by limiting the width of premium “rating bands” for insurance sold in the individual market. This was the result of closed-door lobbying by AARP. This one might pass Congress if voted upon explicitly, but the ACA’s architects hid it to avoid admitting that they were shafting young people.

- Social Security conflates forced individual retirement saving, insurance programs, and massive cross-subsidies, in part to hide the latter.

- So does Medicare. The biggest cross-subsidies are across birth year cohorts but there are plenty of others as well. Don’t get me started on trust fund accounting.

- The employer-side half of FICA payroll taxes that finance most of Social Security and part of Medicare are often framed as if they “are paid by the employer” when their true economic burden is borne by the employee in the form of lower wages. If all FICA taxes were imposed on the employee-side they would be more transparent and less popular.

- A minimum wage increase forces low-skilled unemployed workers to subsidize the wages of the low-skilled employed. Expanding the earned income tax credit is a more transparent way to help the low-skilled unemployed but it puts the costs on budget and in full view. The Left pushes to hide the costs and lies, claiming it’s a free lunch.

- CAFE fuel economy requirements are less transparent than a gas tax that would achieve a similar goal. But gas tax increases are wildly unpopular while raising CAFE standards appear only to make things harder “on the auto companies.”

- A global CO2 cap-and-trade system would have obscured the redistribution of global economic growth from developed economies to developing economies. An explicit and transparent carbon tax imposed only on developed economies would achieve a similar endpoint but would have made explicit this massive proposed global redistribution.

- For years policymakers used Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to subsidize homeowners through hidden credit subsidies. The Left pushed this for low-income homebuyers through affordable housing goals, while elected officials across the political spectrum supported the same thing for all homebuyers through special advantages conferred by government on these two firms.

I could go on. Corporate incomes taxes hide the costs imposed on the people who work for, own, and buy from these firms. Many agricultural subsidies are intentionally obfuscated to enhance their bipartisan support.

Apparently Dr. Gruber thinks it’s OK to lie to American voters when his allies are in power to enact policies that he wants but the voters wouldn’t. He then says American voters are “stupid” both for not agreeing with his value choices and for not figuring out the deception.

I disagree.

When you strip away all the complexity, economic policy is ultimately an expression of elected officials making difficult value choices. If over time these officials make value choices that do not reflect the values of the people whom they represent, they can, should, and will be replaced.

When these same elected officials, and those who advise them, deliberately construct policies to hide value choices that would be unpopular were they transparent and explicit, we end up with two terrible outcomes. We get policies that do not reflect our values, and we re-elect representatives who are lying to us.

President Obama’s odd economic campaign message

President Obama’s economic campaign message is odd. Here is what he’s saying at most campaign events.

-

“There’s almost no economic measure by which we’re not doing better than we were when I took office.”

-

“But people are still anxious. And they’re anxious for three reasons.”

- Overseas uncertainty: ISIL + ebola + Russia/Ukraine;

- “Although the economy is doing better, wages and incomes have not gone up. And the vast majority of growth, productivity increases, profits, wealth has accrued to folks at the very top of the economic pyramid, and we have not seen wages and incomes for ordinary folks go up for a couple of decades. And that makes people feel, even if things have gotten better, that they’re still concerned about not only their future but their children’s futures.”

- “[T]here’s a sense that things simply don’t work in Washington, and Congress, in particular, seems to be completely gridlocked.”

While true, his first point is a self-centered perspective for someone whose job this month is to support the reelection of his party’s Congressional candidates. If President Obama were running for re-election it might be important to compare today’s economy to that when he first took office. But your typical Democratic candidate for Congress isn’t running on President Obama’s economic record, and that six year time frame is irrelevant to candidates like Michelle Nunn and Alison Lundergran Grimes who have not been part of the past six years of governance+stalemate in DC. President Obama’s analysis centers on progress made during his tenure, while many Democratic Congressional candidates want this campaign to be about anything other than him.

President Obama also implies that because the economy is stronger than it was six years ago it is strong today. That does not necessarily follow, especially given the depth of the 2008-2009 recession. The U.S. economy has been climbing out of that hole for five years but it still has a long way to go.

From the President’s perspective, voters feel economic anxiety principally (only?) because of the decades-long maldistribution of economic growth. But if these distributional trends have been building for decades then it is unlikely they can explain a recent change in sentiment.

I suggest instead that voters’ economic anxiety is justified.

- In my judgment the U.S. economy is still quite weak (I won’t get into a statistical cherry-picking battle here) and voters know or can sense it. It can of course be simultaneously true that the economy is at the moment weak and that it is nevertheless stronger than it was six years ago. I think that’s the case.

- The rate of economic recovery over the past five years has been tepid and voters can feel it. Macroeconomists (including President Obama’s first NEC Director Larry Summers) are debating why the rate of recovery has been so surprisingly slow while the President is boasting about the length of the recovery but ignoring its abnormally slow pace.

- While GDP growth accelerated significantly in Q2 of this year to a 4.6% annual rate, that’s after a 2.1% decline in Q1. Should a simplistic straight-line projection of the trend assume the 4.6% rate will continue? If so then the future GDP path should look much brighter than it has over the past five years. Should it instead assume the 2.5% average rate over the past two quarters will continue? That would be moderate growth but nothing to write home about given how far we still are from our maximum potential output. Should we be even more pessimistic as Europe and China weaken? Voters might not be as willing to assume strong growth going forward as a President trying to draw an economic happy face the month before Election Day.

I think voters are anxious about the economy because despite five years of GDP growth the recovery has been too slow to make voters feel good. Today the economy is still weak, employment is still low, real wages aren’t growing rapidly, and stronger future growth, while possible, is by no means certain. In short, voters have good reason to feel economic anxiety.

The upside of all this is that ongoing economic weakness creates an opportunity for sound policies to substantially improve medium- and long-term U.S. economic growth. Policymakers have lots of room to improve policy and plenty of upward potential for a much stronger economy if only we can get the right combination of leaders in Washington and policies in place. The downside is we probably have to wait two more years to have a shot at such a leadership arrangement no matter what happens this November 4th.

(photo credit: The White House)

Return of the low down payment zombie

Mr. Melvin Watt runs FHFA, the Federal Housing Finance Agency charged with regulating Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Yesterday Mr. Watt said:

<

blockquote>To increase access for creditworthy but lower-wealth borrowers, FHFA is also working with the Enterprises to develop sensible and responsible guidelines for mortgages with loan-to-value ratios between 95 and 97 percent. Through these revised guidelines, we believe that the Enterprises will be able to responsibly serve a targeted segment of creditworthy borrowers with lower-down payment mortgages …

Mr. Watt wants to return to the good old days when you could buy a house with 3% down, and in particular he wants poor people to be able to buy a house leveraged 33:1.

This is the return of a terrible idea, a zombie I thought was destroyed when the housing bubble burst. Many homeowners, of all income levels, were too highly leveraged and bought more home than they could afford. They gambled that housing prices would rise forever. Many lost that gamble. They were hurt, their neighbors were hurt, and the financial institutions that held their mortgages were hurt. When the housing bubble burst and financial institutions collapsed, the global economy tanked. Over leverage and tiny down payments (and not just for the poor) contributed significantly to the housing bubble, the financial crisis, and the resulting severe recession.

In May of last year I wrote:

By nominating Mr. Watt the President signals a return to the pre-crisis philosophy of regulating housing finance risk. That is a huge mistake. Mr. Watt should not be confirmed to head the FHFA.

There is a tradeoff you get when policies encourages expanding credit. More people are able to buy things they could not otherwise afford, but at the same time more people end up in credit trouble. This balance clearly went too far in the easy credit direction in the late 90s through the late 00s.

In their never-ending quest to be “pro homeownership,” for more than two decades policymakers and elected officials on both sides of the aisle took every opportunity to expand credit and subsidize home buying. The GSEs’ regulatory structure allowed them to ignore the costs and risks of these actions until it all imploded.

The usual left-right DC housing debate centers on whether one should distort policy to give preferential treatment to poor borrowers. The far left says yes, and many on the right say no. Mr. Watt’s announcement is consistent with the left’s view in that he appears to be considering lowering the down payment requirement for poor borrowers (technically “lower-wealth” borrowers, who will be highly correlated with lower-income borrowers).

But many on the right (including those who opposed aggressive GSE reforms and were quite friendly with Fannie and Freddie pre-crisis) were just as supportive of low down payments as long as they were available to middle- and upper-income homebuyers as well. Think carefully, Congressional Republicans, before you cast stones at your progressive friends on the left. Mr. Watt wants to make it easier for poor people to buy too much house. The problem is the too much house part, not the poor part.

My complaint is not particularly with lowering the GSEs’ down payment requirement for poor borrowers, it’s making this policy change for any borrowers. Policy should not be encouraging or subsidizing (explicitly or implicitly) anyone who buys a house leveraged 33:1, whether he is poor or rich. If policymakers want to encourage homeownership they should encourage responsible homeownership, which means that you have been patient and wise enough to save for a significant down payment.

For many poor people a larger down payment requirement will mean that they either have to buy a smaller house, or work and save longer to afford a bigger down payment, or rent rather than buy. I think all three outcomes are better than encouraging people to buy homes they cannot afford, than gambling (again) that housing prices will always go up, than inflating a new housing bubble, and than creating a new batch of toxic housing-related financial assets based on bad mortgages.

Mr. Watt’s announcement reinforces my view that the GSEs and their regulatory structure should be completely replaced by a purely private housing finance market. Any replacement regulatory structure that allows the government a role in determining the structure of mortgages will be subject to distortion like that which Mr. Watt is about to revive. If the balance of legislative power requires that housing for poor people be subsidized, then the right way to do it is to combine a free market in mortgages with explicit on-budget subsidies for the poor, and with those subsidies targeted at income rather than at making down payments cheaper.

Let’s remember the recent past and not repeat those mistakes anew.

(photo credit: Andrew Becraft)

Kill export subsidies. Kill the Ex-Im Bank.

Imagine the Chinese government decides to help the people of Kenya. To do this the Chinese government buys 5,000 wheeled loaders and excavators from Liugong Machinery and gives them for free to the Kenyan government, Kenyan construction firms, and groups of Kenyan citizens who want to build roads and stuff.

(Real world export subsidies are much smaller, of course, but the principle is the same. Foreign customers of a domestic exporter get taxpayer-subsidized discounts, not totally free stuff.)

Who wins? Kenyan customers and Liugong’s owners and employees, who now have a huge increase in demand for their product.

Who loses? Chinese taxpayers, who must foot the bill, and the owners and employees of Liugong’s Chinese and foreign competitors, who don’t have this generous taxpayer-subsidized benefit and can’t possibly compete with free.

Now let’s journey to America to meet an (imaginary) executive from Caterpillar, an American firm competing with Liugong to sell wheeled loaders and excavators to Kenyans. Caterpillar can’t give their product away, they need to sell it. This executive goes to a U.S. policymaker and asks for a similar export subsidy to what Liugong received from the Chinese government.

Imaginary Caterpillar executive: “Caterpillar is losing business in Kenya to our Chinese competitor Liugong. The Chinese government buys equipment from Liugong and gives it to Kenya. The U.S. government needs to do the same for us. If they don’t we’ll completely lose the Kenyan market to the Chinese. American taxpayers need to put up money to buy Caterpillar wheeled loaders and excavators and then give that machinery to Kenyans. If you don’t, we’ll lose that export business and American jobs.”

American policymaker: “Let me get this straight. We should take money from American taxpayers, use it to buy equipment from your company, and then give that equipment to the Kenyans, all because the Chinese are doing the same thing with your competitor?”

Cat exec: “I agree it sounds silly, but if you don’t do this we’ll lose American jobs. It would be better if neither China nor the U.S. did this, but as long as the Chinese do, you have to as well. Unless you want to put America at a competitive disadvantage and lose the Kenyan heavy equipment market…”

American policymaker: “There’s a difference between what’s good for America and what’s good for one firm in America. China’s policy puts one American company (yours) at a tremendous disadvantage in winning business in one foreign market. I feel bad about that, but I’m not sure the solution you propose makes things better for America as a whole. For instance, while I like Kenya, aren’t you asking me to have American taxpayers subsidize your Kenyan customers? That’s not my policy goal. If I wanted to help Caterpillar owners and employees, wouldn’t it be more efficient to just have the U.S. government write a check to Caterpillar? That way we wouldn’t dilute the help by giving most of it to foreigners.”

Cat exec: “Yes, that would be more efficient, but we both know there’s no way you could sell that to Congress or the American public.”

American policymaker: “So you want me to support a less efficient policy because the more efficient one would be unpopular. What about your American competitor John Deere? Wouldn’t I be giving you an unfair advantage over them?”

Cat exec: “Well, technically, yes, but…”

American policymaker: “Technically nothing. You’re asking me replace one tilted playing field with another. And what if China decides to do the same thing for the Rwandans? Do I have to match those subsidies as well?”

Cat exec: “Unless you want us to lose that business, sure…”

American policymaker: “What if Liugong got its subsidy from the Chinese government through less-than-noble means? What if a Liugong executive’s brother-in-law’s cousin is the guy who works for the key Chinese decision-maker? Are you saying that U.S. taxpayers should target American subsidies for American firms to match foreign subsidies determined by cronyism in a foreign government? Is that right? Where does it end?”

Cat exec: “Well, when you put it that way it doesn’t sound quite as attractive. But surely you don’t want America to unilaterally disarm.”

American policymaker: “Sorry, but I don’t buy your ‘disarmament’ analogy. China’s export subsidies of Liugong don’t only hurt Caterpillar, they also hurt Chinese taxpayers and Liugong’s Chinese competitors. They distort decisions and redistribute economic resources in China in ways that make their economy less efficient. While they undoubtedly help Liugong’s owners and employees, China’s export subsidies harm other parts of the Chinese economy. You’re asking me in turn to help your firm’s owners and employees at the expense of American taxpayers and the owners and employees of your American competitors. I don’t see why I should replicate their mistake here, even the alternative is that your firm loses the Kenyan market to Chinese subsidies. Seems to me the alternative you propose is better for Caterpillar but worse for America as a whole. A better analogy would be if you said I should not quit smoking until all my friends also quit. I should quit smoking if it’s healthier for me even if my friends continue to smoke. If China wants to harm itself, there’s no reason I should do the same just to match their mistake.”

Cat exec: “And therefore you’re going to force Caterpillar to compete on an unlevel playing field with Liugong. You’ll be responsible for the layoffs at Caterpillar that result because you refused to help us.”

American policymaker: “The alternative is that you want me to force American taxpayers to subsidize foreign consumers and the owners and employees of one American firm, and to create a new titled playing field at the expense of the owners and employees of your American competitors, based in part upon decisions made in foreign capitals that may have been determined by cronyism. You agree that this policy is less efficient than one that would be unpopular in the U.S., and you’re advocating this one because you think you can disguise that it’s a worse policy. No thank you.”

Cat exec: “How about if, rather than buying the equipment in total, you just give us a partial taxpayer subsidy? We can make it either a direct subsidy or a taxpayer-backed loan guarantee, and we can do it through the government run Export-Import Bank. That way nobody will understand it.”

My view

The U.S. government should not engage in industrial policy, choosing to help certain American firms and thereby indirectly punishing other American firms. Government should not be picking winners and losers.

American taxpayers should not be subsidizing any particular subset of American business owners and/or workers. American taxpayers should also not be subsidizing foreigners, even when they are foreign consumers of American exports.

Export subsidies are bad policy. Even when well-intentioned and designed to “level the playing field” to match other countries’ export subsidies, they create other tilted playing fields and do more harm to the economy as a whole than the problem they purport to solve for one firm. They also create opportunities for cronyism and other forms of influence-based rent-seeking.

Deep and liquid private credit markets exist today that did not exist when the Export-Import Bank was created in the 1930s. Ex-Im’s primary function now is to pass though implicit taxpayer subsidies to a select group of American firms.

Export subsidies should be eliminated and the Ex-Im Bank should be killed. Export credit finance should be done, without subsidies, by private markets.

Ryan v. Obama on short-term deficits

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan released his proposed budget resolution today. As I’ve done in the past I’m going to compare his proposal to the President’s budget. I’d like to include Senate Budget Committee Chairman Patty Murray’s proposal but she has chosen not to do a budget this year.

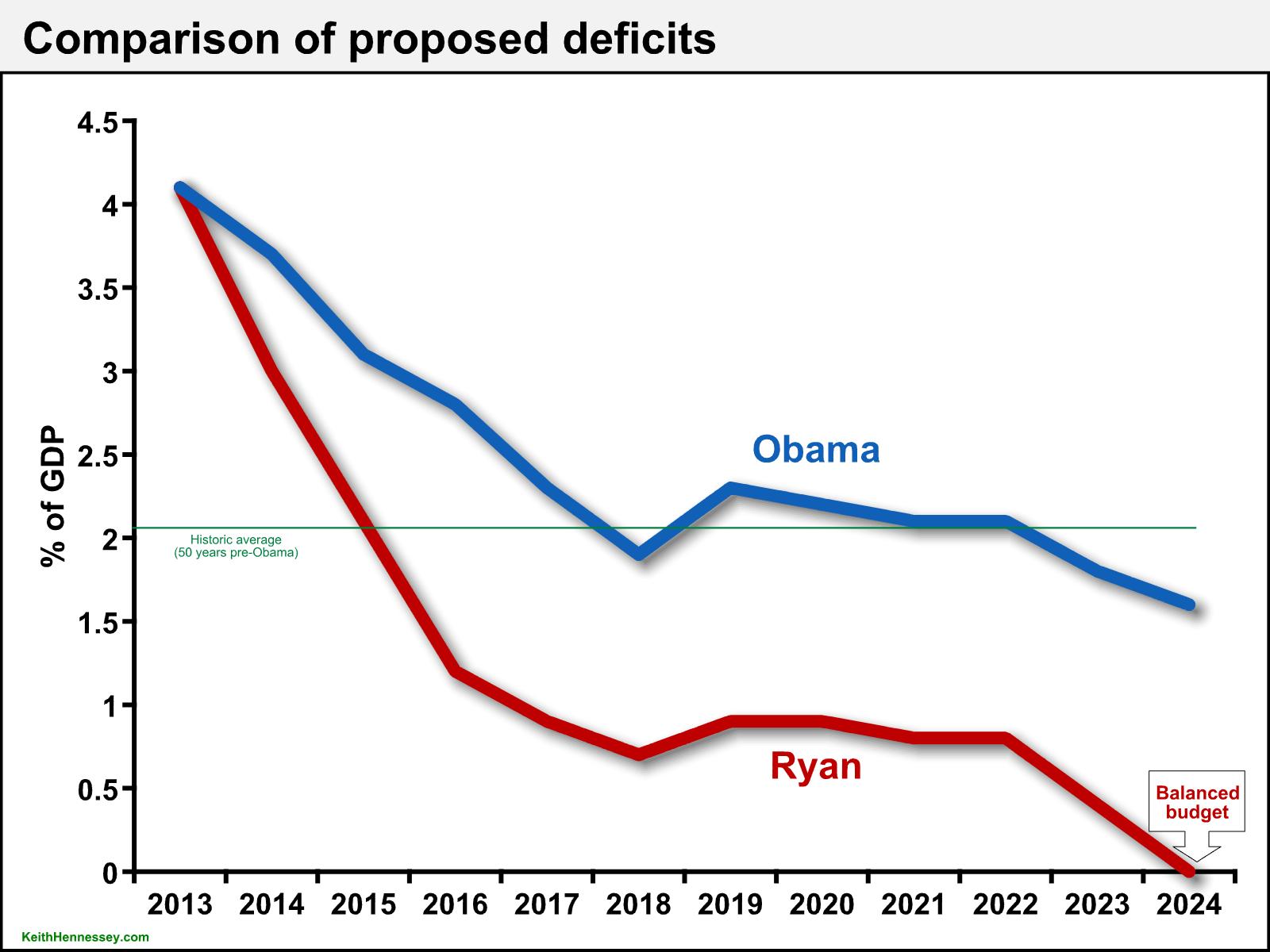

In this post I’m just going to compare the short-term deficit and debt effects of the two proposals. While I’d like to use comparable numbers, CBO has not yet rescored President Obama’s proposal because the President released his budget six weeks late. So for now I’ll compare Ryan’s numbers to Obama’s. That is suboptimal but the best we can do for now, and I am confident it doesn’t change the overall picture. Let’s start with deficits.

A few things jump out.

- Chairman Ryan’s deficits are lower than President Obama’s throughout the budget window.

- The difference is significant in the early years.

- President Obama’s budget would reduce deficits below their historic average only after he leaves office.

- The gap between the two stabilizes around 1.5 percentage points of GDP.

- Chairman Ryan’s budget gets to balance, President Obama’s does not.

The most politically potent aspect is balance vs. no balance.

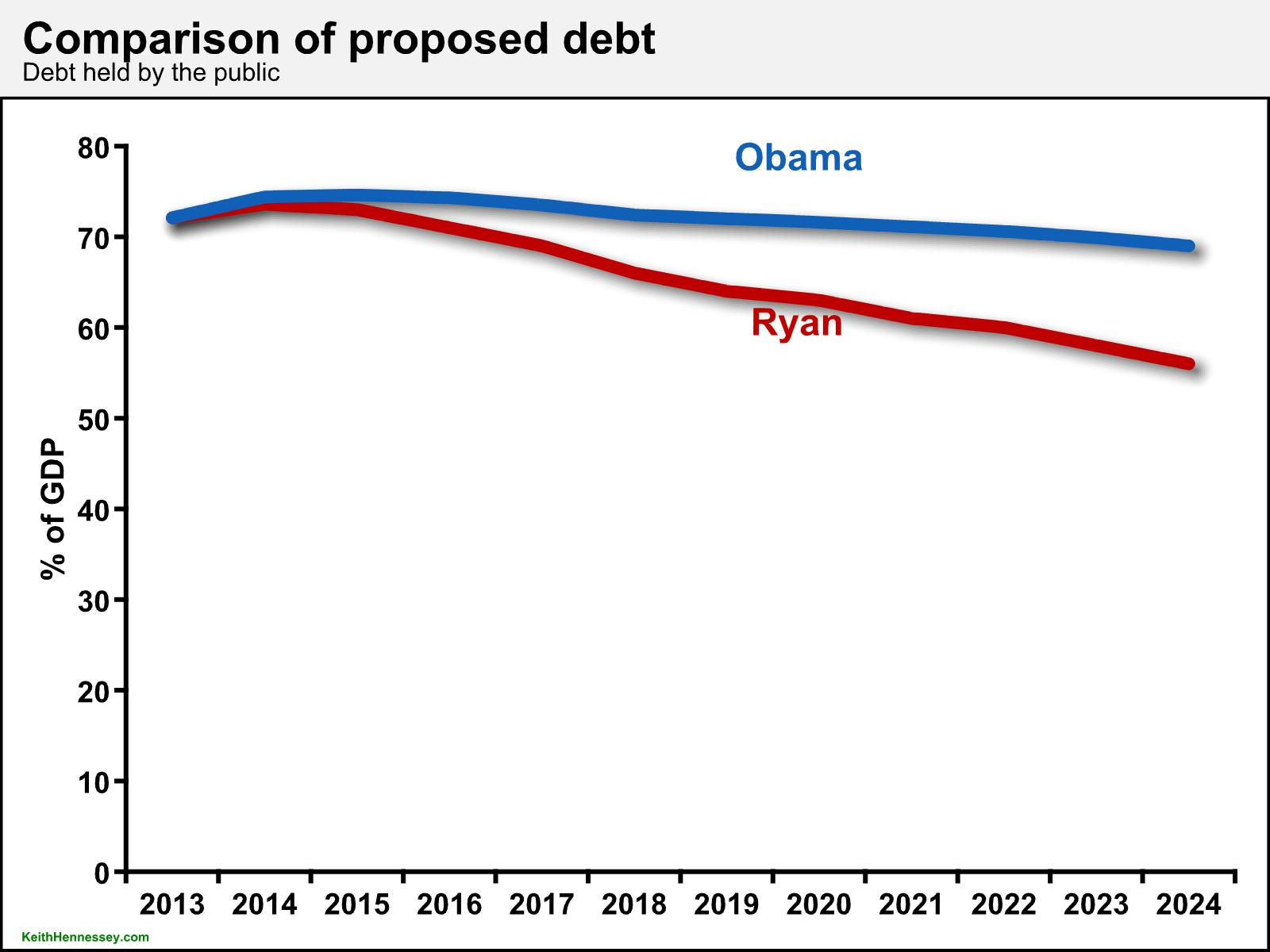

Now let’s compare the short-term debt effects of the Ryan and Obama budgets. Debt held by the public is (sort of) the accumulation of past deficits and a few surpluses.

- Both propose to reduce debt/GDP over the next decade.

- Chairman Ryan’s debt is in all cases lower than the President’s.

- Over time the difference is significant: Ryan’s 10th year level is 13 percentage points lower than Obama’s (caveat: This will change a bit when we get the CBO rescore of the President’s budget).

The notable points here are (1) the growing gap over time and (2) the President’s decision to reduce debt/GDP over time, albeit slowly. In past years he was content to stabilize debt/GDP in the short run.

Fiscal politics and strategy

At first glance the Obama and Ryan budgets appear quite similar to what each proposed last year. Because the downward slope is so gentle, President Obama’s declining debt/GDP path is more significant politically than as a policy matter. It allows him to say his budget would reduce debt over time, at least in the short run. He couldn’t say that last year.

In this midterm election year, Chairman Ryan has offered House Republicans a tremendous political advantage: BALANCE. This reminds me of 2011.

The two political parties have traditionally competed over which party was “the party of lower deficits and less debt.” Many elected officials and their campaign advisors have traditionally seen significant political advantage in labeling their opponents as being for higher deficits and more debt.

This debate is somewhat silly, as the principal fiscal policy difference between the two parties has usually been more about the size of government than about which party wants to borrow less from the future. Nevertheless, the political effects of deficit/debt comparisons are significant.

The same is true for a balanced budget. The economic difference between balance and a 1 percent deficit is not dramatically different from the difference between a 1 and a 2 percent deficit. But the politics of a balanced budget can be powerful.

In 2011 President Obama proposed his budget in February. Chairman Ryan then proposed a budget with a significantly more aggressive deficit and debt reduction path, thus seizing the political advantage in this partisan competition. The numbers clearly showed that (House) Republicans were for much lower deficits and debt than the President.

And then the President modified his budget in April, proposing significantly lower deficits than he did two months prior. He purported to match the deficit reduction in the Ryan budget–this was a lie, but he claimed it. (See Bob Woodward’s book for details on both the internal process and the lie.) What’s significant today is that in 2011 President Obama reacted to the political weakness he then faced by being for higher deficits and debt than House Republicans. He proposed more policy changes, some of which involved more political pain, just so the could claim to match House Republicans on deficits and debt.

Fast forward three years. It’s happening again.

Chairman Ryan has teed up a significant political tool for House Republicans: they can be for a balanced budget, in contrast both to President Obama’s higher deficits and debt and to the Senate Democrats’ lack of a budget.

This is a potent weapon for the mid-term election battle. Congressional Republicans can be not just opposed to something unpopular (Obamacare, of course), but for something popular. They can expand their topline economic message to have three legs rather than just one.

<

ol>

I’ll end with three important strategy questions:

- Are House Republicans a governing majority? Ryan’s balanced budget provides a political advantage only if House Republicans pass it. Can Chairman Ryan and Boehner/Cantor/McCarthy find 218 R votes for the Ryan budget?

- Will Republicans recognize the political and rhetorical advantage that a balanced budget gives them and integrate it into their core election message, putting it on a level playing field with both “weak Obama recovery” and Obamacare? Or will they bet all their mid-term election prospects on a single issue?

- Will President Obama react to House passage by modifying his budget proposal as he did in 2011? Or will he cede the rhetorical high ground on deficits, debt, and a balanced budget in favor of attacking the details within the Ryan budget?

Response to the President’s comparison to European growth rates

At that Manhattan fundraiser last night President Obama repeated one of his more frequent recent economic lines:

Over the last five years, our economy has recovered faster and stronger from the worst financial crisis and economic crisis since the Great Depression, better than any other developed country on Earth.

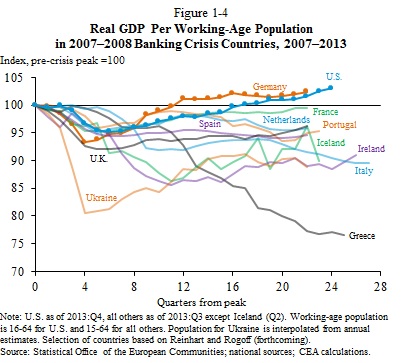

President Obama’s is drawing on the Economic Report of the President released by his Council of Economic Advisers on Monday. Here is the relevant chart, showing the U.S. at a higher relative GDP level than the major European economies, with 2007 as the starting point for the comparison.

Here is the CEA’s accompanying text:

<

blockquote>

(Technical note: “GDP per working-age population” is weird. I wonder what this same comparison with the more conventional “GDP per capita” looks like.)

This provokes three responses.

- Apparently we’re supposed to feel good that the U.S. economy has grown more rapidly than the major European economies. But Europe had a second financial crisis during this time period, one which might still not be over! So the U.S. economy, recovering from one severe financial crisis in the past six years, is performing better than the European economies which have suffered two crises during that same time? Talk about setting a low bar.

-

While a relative comparison might in theory be interesting, it’s not very useful. We should care about how the American economy is doing in absolute terms, and relative to the potential of the U.S. economy. Is the U.S. economy growing as fast as it possibly can? How big of an output and employment gap do we have to close? (Answer: we’re about 6 million jobs short.) If Europe were to go into recession the relative U.S. position would be even stronger, but surely that wouldn’t be a good thing, right? We should want the U.S. and Europe both to grow faster, even if that were to mean a smaller relative advantage for the U.S., yes? Greater relative growth doesn’t teach us much that we can use.

-

The conclusion that “We’re growing faster than Europe so therefore our policies worked” makes no sense to me. And I write this as someone who helped enact and implement some of those U.S. policies (including TARP, the money market mutual fund guarantees, and the first tranche of auto loans). I think some of these policies worked as desired and helped end the financial crisis and make the ensuing recession shallower. I differ with Team Obama on how much the fiscal stimulus in particular contributed to those positive growth effects, and whether the additional growth from fiscal stimulus was worth the added debt costs. But whatever conclusion you reach about the growth benefits of any of those policies, you can’t get there from comparing the recent U.S. growth path to that of Europe. There are way too many other things going on, both in the U.S. and especially in Europe with its two crises, for anyone to be able to isolate the effects of just the U.S.-specific policies. If you want to argue that the U.S. policies worked as intended, you need to find another way to make the case.

I think the President’s statement, that the U.S. economy has recovered more rapidly than other major developing economies, is technically correct. But it’s a sad thing to boast about, it’s not a meaningful measure, it’s not the standard we should use, and it doesn’t support the argument that U.S. policies made a major difference in averting a substantially worse outcome.

Response to the President on economic anxiety

At a Manhattan fundraiser this evening President Obama said the U.S. economy has “bounced back”:

Over the last five years, our economy has recovered faster and stronger from the worst financial crisis and economic crisis since the Great Depression, better than any other developed country on Earth. And you can take a look at the charts and see that because of the actions we took — because of the Recovery Act, because of the Fed — because of swift, coordinated action, we have bounced back.

We’ve created 8.5 million new jobs over the last five years. We’ve had four years of consecutive job growth as well as economic growth. We have seen an auto industry that was basically flat-lining rebound in ways that very few people would have anticipated. The stock market is close to the highest that it’s ever been; close to $10 trillion of wealth has been recovered that was lost.

Presidents always want to be optimistic, but even so this is a very positive framing. He then offers his analysis of why, notwithstanding this good news, Americans are so “anxious and uncertain” about their economic future:

That’s not bad. And yet, if you talk to folks around the country, there is still enormous anxiety and people feel uncertain about their futures, and more importantly, their children’s futures. And why is that? Because although we have rebounded and we are growing and there are all kinds of indicators that tell us that the 21st century can be the American Century just like the 20th was, that growth has been uneven and the beneficiaries of that growth have been uneven.

Set aside for the moment the irony of President Obama saying the problem is increasing income inequality when speaking at a $32,400/plate fundraiser in Manhattan. There’s a better explanation than the increasing income inequality explanation offered by the President. CBO gives it to us:

Employment at the end of 2013 was about 6 million jobs short of where it would be if the unemployment rate had returned to its prerecession level and if the participation rate had risen to the level it would have attained without the current cyclical weakness.

President Obama’s thesis is that the economy has “bounced back,” things are looking pretty good in the aggregate, and people are down because income inequality is increasing and the middle class isn’t benefiting sufficiently from economic growth.

The reality is that the economy is growing, but way too slowly, and only fast enough to roughly keep up with population growth. The economy is still about 6 million jobs short of where it should be if it were firing on all cylinders. Income inequality is increasing, but that trend goes back to the 1970s. It’s not a credible explanation for recent economic pessimism.

President Obama’s diagnosis is wrong in two respects. While the economy is growing slowly, it has not “bounced back.” And people are pessimistic about the economy because there aren’t enough jobs, period. Even worse, President Obama has no proposal to even try to fix that.

(photo credit: Family O’Abé)

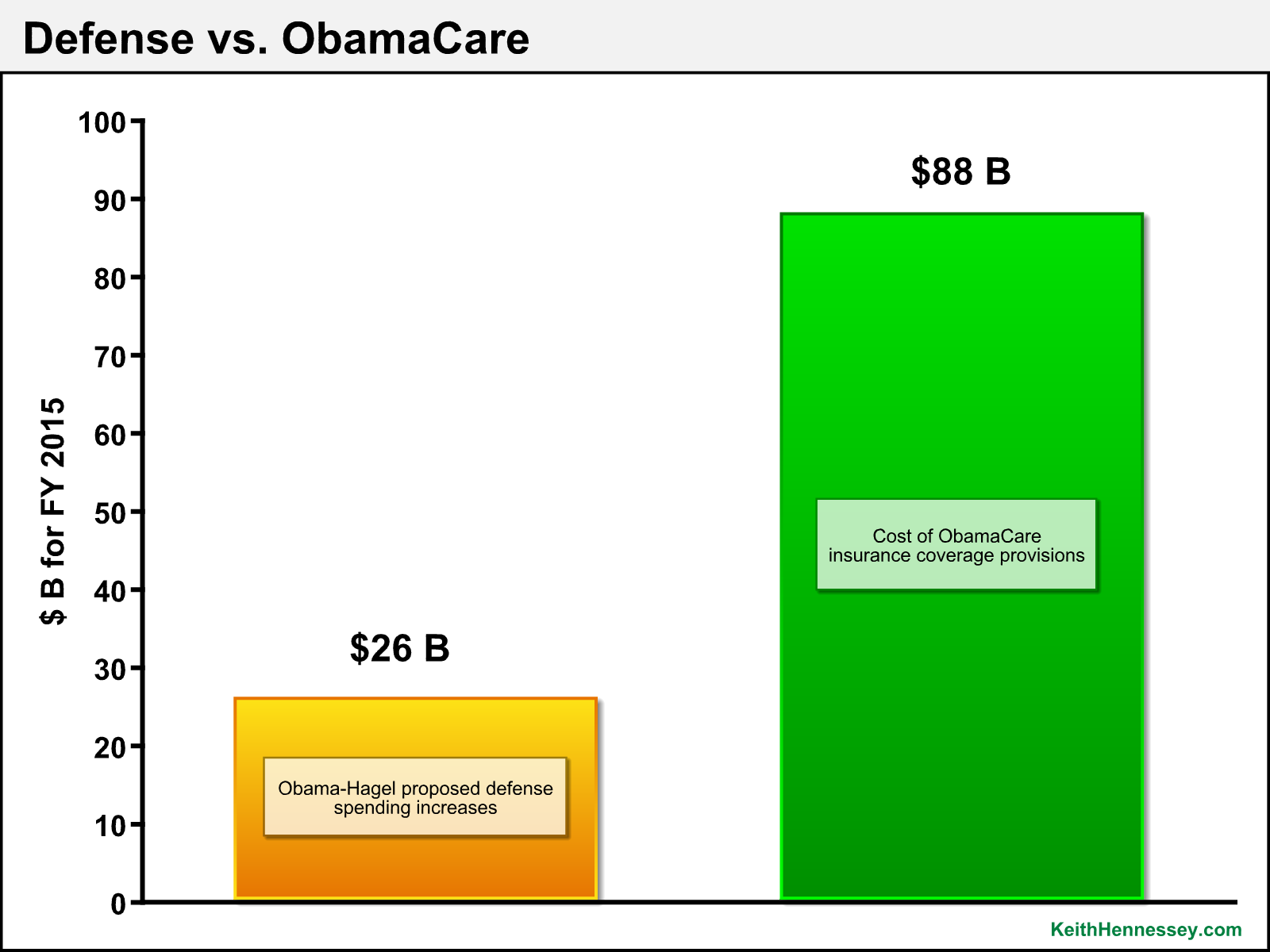

Defense v. ObamaCare

DEFENSE SECRETARY HAGEL: To close these gaps, the President’s budget will include an Opportunity, Growth and Security Initiative. This initiative is a detailed proposal that is part of the President’s budget submission. It would provide an additional $26 billion for the Defense Department in Fiscal Year 2015.

Source for $88 B number: Congressional Budget Office, “Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Care Act–CBO’s February 2014 Baseline,” Table 1 (Net cost of coverage provisions for FY 2015).

Message to Governors: Biden v. Obama

Here is VP Biden, speaking this morning to all Governors:

THE VICE PRESIDENT: It’s great to see you all. And I don’t know about you all, I had a great time last night and got a chance to actually do what we should be doing more of — talking without thinking about politics and figuring how we can solve problems.

And here is President Obama, speaking at a dinner last Thursday night to just the Democratic Governors:

THE PRESIDENT: Now, unfortunately, state by state, Republican governors are implementing a different agenda. They’re pursuing the same top-down, failed economic policies that don’t help Americans get ahead. They’re paying for it by cutting investments in the middle class, oftentimes doing everything they can to squeeze folks who are bargaining on behalf of workers. Some of them, their economies have improved in part because the overall economy has improved, and they take credit for it instead of saying that Obama had anything to do with it. I get that. There’s nothing wrong with that. But they’re making it harder for working families to access health insurance. In some states, they’re making it harder even for Americans to exercise their right to vote.

How CBO’s minimum wage analysis changes the debate

CBO’s intellectually solid new analysis concludes that the proposal, endorsed by President Obama, to raise the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour by 2016 would result in higher wages for some and destroy jobs for others. CBO’s most important conclusions are that this proposal would:

- likely result in 500,000 fewer workers, with a range of roughly 0 to 1 million fewer;

- increase wages for about 16.5 million workers who now have wages between $7.25/hour and $10.10, as well as for some others who now have wages a bit above $10.10.

I think CBO’s analysis is improving the minimum wage debate. President Obama and his allies have been selling this proposal as a free lunch, a policy that will raise pay for some with no costs for anyone: “Give America a raise.” Proponents of raising the minimum wage now must contend with a reputable nonpartisan analysis that the proposal has costs as well as benefits. Congress must decide whether higher wages for some are worth destroying jobs for others. Every responsible news story will now include a sentence like, “At the same time, the Congressional Budget Office projects the President’s proposal would result in lost jobs for half a million low-skill workers.”

I doubt the new numbers will change the minds of many proponents of a higher minimum wage. If you were previously inclined to support an increase, either for policy or political reasons, you can easily use CBO’s analysis to reinforce that conclusion: there are 16-31 times as many winners as losers.

The principal impact will come for a Member of Congress who thinks (knows?) that wage controls are bad policy and who opposes a higher minimum wage on policy grounds but was previously afraid to take the political risk to vote no. CBO has made it easier and more credible for this Member to explain to his or her constituents why he will vote no and why that’s good policy for those trying to enter the workforce. Here’s an example.

Q: Congressman, why do you oppose raising the minimum wage? Don’t you want to give Americans a raise?

A: You’ve heard the saying “There’s no such thing as a free lunch?” The President’s proposal to raise the minimum wage would put between half a million and a million low-skilled people out of work. Sure it would mean higher wages for some, but it would destroy jobs for others, and those others are the lowest wage, lowest skilled workers whom we should want in the workforce. It’s particularly important to have as many low-skill jobs available as employers want to offer so that people can grab the first rung of that ladder of opportunity and start to climb.

I appreciate that others may make a different judgment call, but when our biggest economic problem continues to be that not enough people are working, I want to make it easier for employers to hire people, not harder.

This Congressman or woman (probably a Republican) could have made this argument before CBO’s report, but now he has CBO to back up his numbers and his logic. That helps mostly with the press and also with some voters who are undecided on the merits. In the past Congressional Republicans who opposed a minimum wage increase would typically argue that it “hurts small businesses.” Now they can and should argue that it “will destroy jobs for low skill workers.”

In short, CBO’s analysis makes it easier for a free market member of Congress both to vote against expanding wage controls and to convincingly explain why doing so is motivated by a compassionate goal.

The Obama team had two options in choosing to react to the CBO report. They could have accepted CBO’s analysis, embraced the tradeoff between higher wages and fewer jobs, and used CBO’s numbers to support their judgment call on that tradeoff.

Instead, they went the other way, sticking with their disingenuous “free lunch” logic and attacking CBO’s credibility. The path they chose was both intellectually and politically weaker. Now they’re fighting with CBO (rarely is there an upside to that), they’re indirectly highlighting CBO’s conclusions for the press, and they’re fighting what we all learned in first semester microeconomics, that when you raise the price of something people buy less of it. They are also making this not just a dispute about the measure of the costs and benefits, but whether there are any costs to their proposal. They will lose that fight, especially with CBO on the other side.

Team Obama could have argued “We agree with CBO that there are costs to raising the minimum wage, and we think those costs are worth it.” But if they had done this, they would be forced to acknowledge that opponents of raising the minimum wage have a point, that one can want to help poor, low-skilled people and just come to a different conclusion about whether this proposal does so. Had Team Obama granted this point they would have sacrificed their specious claim that opponents of a minimum wage increase hate the poor. This would then become a disagreement about judgment calls on a difficult policy tradeoff (which it is for many), not a battle between the forces of good and evil.

In a market economy prices play the central role in balancing supply and demand. Government should let market forces determine prices. In my view the only case where there’s even theoretical support for government intervention in the price mechanism is when there’s an externality, and even then I’d be cautious to make sure that a well-intentioned but poorly implemented government interference in a market price to address an externality doesn’t do more harm than good.

If you don’t like the results of how a free market allocates resources, then adjust the outcome through explicit after-the-fact transfers, not by interfering in the market mechanism that determines wages or prices. If you want to help the poor more now, expand the Earned Income Tax Credit and use taxpayer dollars to subsidize those lowest on the wage scale rather than forcing an employer to pay them more.

Policies that destroy jobs are bad. Let’s instead maximize the opportunities for people at all levels of education, skills and abilities to find work.

(photo credit: Maryland GovPics)