Error of Commission

The Wall Street Journal reports:

White House and congressional leaders reached a tentative deal aimed at establishing a bipartisan commission to tackle the soaring federal budget deficit, in what is likely to be a central element of President Barack Obama’s fiscal 2011 budget, people familiar with the talks said.

Meeting Tuesday night at the White House, Vice President Joe Biden, White House budget director Peter Orszag and Democratic leaders agreed the commission would report back at the end of 2010 with a path to bring this year’s projected $1.4 trillion deficit from about 10% of gross domestic product to 3% by 2015.

The commission would also submit recommendations on taxes and spending on entitlements, such as Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security. House and Senate Democratic leaders promised the recommendations would be submitted to Congress for an up-or-down vote after the midterm elections this year, these people said.

The 18-member commission will include six people appointed by congressional Democrats, six appointed by congressional Republicans and six appointed by the president. Of the president’s six, two will be Republicans and four will be Democrats.

Under the deal, the commission will be created by an executive order and laid out in the fiscal 2011 budget that Mr. Obama will submit to Congress Feb. 1.

Republican leaders weren’t part of the talks, and the panel can work only if GOP leaders select members to serve on it.

Let us assume this reporting is accurate. I will compare the rumored Administration proposal to the Conrad/Gregg legislative proposal, the Bipartisan Task Force for Responsible Fiscal Action Act. Senator Kent Conrad (D-ND) is Chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, and Senator Judd Gregg (R-NH) is the Ranking Republican Member of that committee.

I will highlight important differences in red.

| Administration | Conrad-Gregg bill | |

| Created by | President | Congress & President |

| Created through | Executive Order | new law |

| Goal | short-term | long-term |

| reduce deficit to 3% by 2015 | significantly improve the long-term fiscal imbalance | |

| Scope | taxes & entitlements | taxes & spending |

| Membership | ||

| How many members? | 18 | 18 |

| Who serves? | ?? SecTreas + 1 other Admin. |

current Members of Congress, SecTreas + 1 other Admin. |

| Partisan balance | 12 appointed by Ds, 6 by Rs | 10 appointed by Ds, 8 by Rs |

| Chair structure | ? | bipartisan co-chairs |

| Executive Director | ? | chosen jointly by co-chairs |

| Voting | 14 of 18 to make recommendations |

14 of 18 to make recommendations |

| Reporting date | In 2010 after Election Day | Nov. 15, 2010 |

| Fast-track process | None. Political commitment by Pelosi & Reid to have an up-or-down vote, but no rule changes mean they can’t bind Congress to that. Majority vote and 60 Senate votes needed to pass a law. |

limits Congressional rules to mandate up-or-down House & Senate votes by Dec. 23rd. 3/5 of House & Senate required to pass. |

In my experience, there are four reasons to create a commission:

- You want to learn or investigate something: 9-11 Commission, Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.

- You want to create an external credible body of “wise men” to produce consensus recommendations to build broader political support for politically painful policy changes: 1982 Social Security Commission.

- Elected officials want to give themselves political cover to implement painful policy changes, by delegating control of the details to someone else: Base Realignment Commission (BRAC).

- You want to duck an issue for a while and you need an excuse.

The Conrad-Gregg task force bill is trying to delegate control to change the law. The rumored Administration proposal is trying to provide an excuse while they duck a hard policy issue in an election year.

A commission that is trying to actually make changes to law must be credibly balanced and it must have formal authority to bind policymakers. The Conrad-Gregg proposal has both. The rumored Administration proposal has neither.

I am torn on whether to support the Conrad-Gregg proposal. I instinctively don’t like it. I fear that this structure would lead to huge tax increases. I lean against Congress delegating their authority, and generally abide by the maxim that “the problem isn’t the process, the problem is the problem.” But I do feel comfortable saying that Conrad-Gregg is an intellectually honest and credible commission proposal, albeit one that might lead to a policy outcome that I would hate. If you are going to create a commission like this, then this is the most balanced proposal I have seen so far.

In contrast, the rumored Administration proposal is not credible.

- The President’s commission would duplicate his budget proposal from last year. The goal of the rumored new Presidential commission would be to reduce the federal budget deficit to 3% by 2015. But last year the President budget included specific policy proposals to hit that same goal! The President’s budget, proposed February 26, 2009, claimed to reduce the budget deficit to 3.0% by 2015 (Table S-1). (CBO says it misses this mark and would result in a 2015 deficit of 4.3%, but I’m focusing now on the Administration’s claim.) The Mid-Session Review, published August 25, 2009, falls back to only trying to reduce the deficit to 3.9% by 2015 (Table S-1). So the President would now propose a 12-6 commission to meet a goal that he argued his budget met 11 months ago with specific proposals?!? That makes no sense.

- The President’s commission would address the wrong timeframe. The commission’s goal is to focus on the next six years, rather than the even bigger long-term fiscal problem. Since I arrived in Washington in 1994 there has been a consensus that the hard fiscal policy problem is the long-term one, not the short-term one.

- The President’s commission would have a predetermined outcome. Since The President, Speaker Pelosi, and Leader Reid would appoint two-thirds of the members, and there appears to be no supermajority requirement, it’s easy to predict the final recommendations: huge tax increases, and only trivial entitlement spending reductions. Republican appointees would have no leverage and would be easily ignored. Update: 14 of 18 members are needed to approve recommendations.

- The President’s commission does not create any binding fast-track process. Leader Reid cannot unilaterally bind 100 Senators to an up-or-down vote and no amendments. Even if a commission were to produce unanimous recommendations, Republicans should fear that a Democratic Senate majority would use those recommendations as a starting point, substitute even more tax increases for whatever spending cuts are in the recommendations, and then pass the bill. Scott Brown’s election as the 41st vote has little effect on this dynamic, since the changes would probably happen in committee. Any commission created by Executive Order has this weakness: it cannot bind Congress.Only Congress can tie itself to the mast.

The President’s commission does have a political advantage. If the press treats it as credible, he may get away with substituting it for real short-term policy proposals in his budget, and with completely ducking the even more important long-run fiscal policy debate. I am just guessing here, but if the upcoming President’s budget contains a large amount of deficit reduction and labels it “deficit reduction from bipartisan commission recommendations,” then we will have confirmed the commission’s true purpose. Look for the magic asterisk in the budget proposal.

The press should also ask the Administration if the commission’s mandate would allow it to recommend repealing all or part of (1) the stimulus, and (2) a potential new health care law. Whether or not the commission proposes such changes, are they allowable within the commission’s mandate?

Yes, CBO scores the health care bill as deficit neutral (with huge caveats), but enactment of that law would make future deficit reduction efforts much harder because the bill would use some of the easiest and biggest Medicare savings proposals to offset new government spending. If the Administration’s answer is, “No, the commission can propose changes to everything except the spending and tax changes we have implemented over the past year,” then it reinforces the true nature of this proposal.

If you’re concerned about the deficit, the place to start is by not creating a new trillion dollar entitlement program.

The two bill strategy for health care legislation

I am getting questions about a two bill strategy for health care if Scott Brown wins in Massachusetts today. Let’s call it option five relative to my prior list of four.

This strategy combines two options from my prior post: the House would pass the Senate bill, and they would initiate a new reconciliation bill. The sequencing matters, and to keep liberals onboard the reconciliation bill would probably have to come first.

I will be generous and give it a 2% probability. It’s an interesting idea in theory. In practice it would be a nightmare to execute. If Mr. Brown wins, the only path to Presidential success may to be try to get the House to pass the Senate-passed bill without amendment.

How they might do it (in theory)

- Democratic leaders finish negotiating the substantive compromise at the White House.

- They get it scored and sell it to their members. They still need 218 House votes, but in this scenario they need only 50 Senate votes (the VP breaks ties). That’s a huge advantage for Democratic leaders.

- Assuming the Senate-passed bill will become law, draft a new bill that contains the differences between the negotiated deal and the Senate-passed bill. For example, if the “Cornhusker Kickback” drops out of the negotiated deal, then bill #2 would repeal that provision as if bill #1 were already law.

- Draft bill #2 as a reconciliation bill. (This is hard.)

- The House report bill #2 out of three committees unscathed: Ways & Means, Energy & Commerce, and Education & Workforce.

- The House Budget Committee packages all three committee products into a reconciliation bill and reports it to the House floor.

- The House passes a rule and this reconciliation bill with 218 votes.

- The Senate Finance Committee and Senate HELP Committee report the same bill text out of their committees, again unamended.

- The Senate Budget Committee packages the two committee products together into a single reconciliation bill and reports it to the Senate floor.

- Leader Reid proceeds to the bill (simple majority vote).

- Debate is limited to 20 hours. Amendments are unlimited but must be germane to the bill.

- Under reconciliation rules, no filibuster is possible. As long as the bill has been drafted not to violate the budget resolution (difficult), Leader Reid can pass the bill with a simple majority (51, or 50 + VP).

- After the Senate passes the reconciliation bill, they work out differences with the House if any were introduced in the process. They do this either by ping-ponging the reconciliation bill, or through a conference with the House. In either case, they never need 60 votes as long as they stay within the bounds of reconciliation.

- After the identical reconciliation text has passed both the House and Senate, then the House takes up and pass the Senate-passed bill #1.

- Both bills go to the President for his signature. He signs bill #1, then bill #2.

What could possibly go wrong?

Too many failure points

The above option has a huge advantage: it requires only 50 Senate Democrats to concur. It therefore avoids the Brown problem and the ongoing Nelson/Lieberman risks. This scenario works procedurally if you have a rock-solid unified (218 House + 50 Senate) alliance. This option allows up to 9 Senate Democrats to “walk” and vote no on the reconciliation bill, so the vote counting challenge shifts to the House.

But as one expert said, there are too many potential failure points in this strategy.

As I wrote this weekend, the Democrats’ challenge is not procedural. Their challenge is keeping cohesion within their legislative alliance when it is under massive political strain. Remember that Republicans, who are procedurally almost irrelevant in this strategy, would be pounding away rhetorically as we approach Election Day.

Here are just a few of the potential failure points:

- Can all of the changes from the Senate-passed bill to the negotiated agreement be drafted in a way that complies with the Byrd rule? (I doubt it.)

- Will the spending and tax changes in bill #2 comply with the budget targets for reconciliation required by the budget resolution? (No one knows until there’s a CBO-scored agreement.)

- Will members of the three House and two Senate committees support the deal through committee markup, withhold on offering amendments, and oppose Republican amendments?

- Assuming that bill #2 contains the more liberal parts of the negotiated agreement. Will moderate and nervous House Democrats vote for such a bill?

- Will Senate Chairmen Baucus and Conrad, both of whom qualify as “moderates” in the Democratic caucus, go along with such a strategy?

- Will Leader Reid be willing to expose his nervous Members who are in-cycle (up this November) to a long series of painful floor votes from Republicans?

- This process takes a long time (absolute minimum of three weeks after a deal is negotiated, and probably much longer). At the end of this process, will beat-up House Members still be willing to vote for bill #1?

I could go on. This is a nightmare from a member-management standpoint. Counting votes on one bill is hard. Trying to make two bills work together as one is nearly impossible.

Variant

You’ll notice that I structured this option so that the House would pass the Senate-passed bill only after the reconciliation bill was complete. In theory the order could be reversed, but why would a House liberal agree to that? Then you’re just hoping the reconciliation bill makes it all the way through the process. Moderate House Democrats could simply refuse to vote for the reconciliation bill and it would die, leaving them with an enacted law that is the Senate-passed bill. I see no logical reason why House liberals would give up their leverage point, which is the sequence of votes.

Updating my predictions

I need to update my predictions (published Sunday) to reflect public comments by Democratic leaders and this new option. Here are my new predictions, assuming a Brown victory:

- Ram it through: was 25% -> now 10%

- House folds: was 25% -> now 30%

- Reconciliation: was 3% -> now 1%

- Deal with Snowe: steady at 2%

- Two-bill strategy: 2%

- Collapse: was 45% -> now 55%

You can see that I’m increasing the chance that the bill collapses if Brown wins. I’m also shifting the balance between the first two options heavily toward the House folding. That’s not because I think it’s a good option or I can imagine it working. It’s simply because the intensity at the top for an accomplishment is enormous, and all other options look worse. The leaders would face vote counting challenges with pro-labor members, pro-life members, the Hispanic caucus on illegal immigrants, and many, many others.

This means my pre-election probabilities change to:

- Law: was 74.5% -> now 69.5%

- No law: was 25.5% -> now 30.5%

And my results if Brown wins today are now:

- Law: was 55% -> now 45%

- No law: was 45% -> now 55%

I find it fascinating that a Senate election could shift the main locus of decision-making on this issue to the House. For months the focus has been on how Leader Reid holds 60 votes. If Mr. Brown wins, this becomes principally a House game, not a Senate one. And while I have learned never to underestimate Speaker Pelosi’s ability to get the votes she needs and hold her caucus together, a Brown victory could make that extremely difficult.

I will be watching Speaker Pelosi for signals about how the process will move forward. She’s got the health care process ball if Brown wins in Massachusetts today.

(photo credit: Gordian Knot by Kecko)

Part 3: My projections for health care reform

This is the third of three posts on how the Massachusetts special election interacts with health care reform:

- Part 1: What happens to health care legislation if Scott Brown wins Massachusetts?

- Part 2: Procedural options for health care after a Brown victory

- Part 3: My projections for health care reform

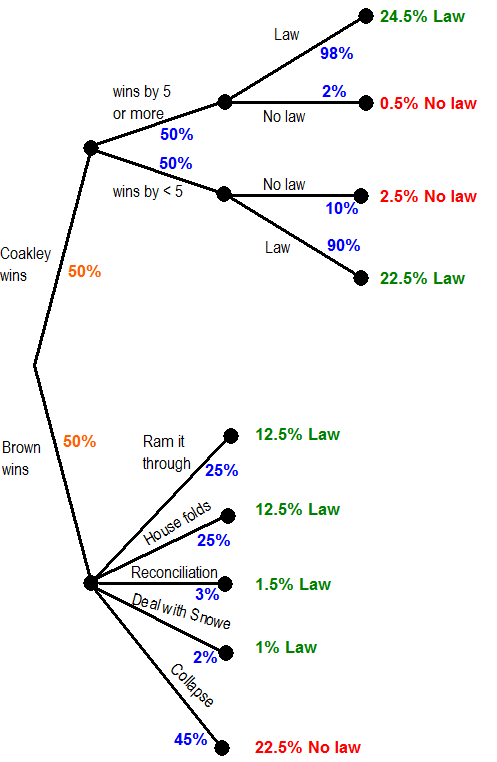

After a lot of feedback and hard thinking, I conclude that this is extremely difficult to predict. Here are the subjective judgments I’m making:

- I assume the Massachusetts race is a toss-up.

- I assume there is a difference in the impact on health care legislation of a slim Coakley win and a big Coakley win. I am setting the breakpoint at +5.

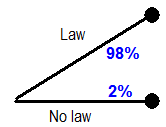

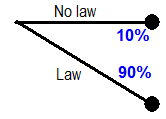

- I assume a 98/2 chance of legislative success (signed law) if Coakley wins big, and a 90/10 chance if she wins by a slim margin.

- If Brown wins:

- I’ve got collapse at 45%.

- I assume reconciliation and a deal with Senator Snowe are super-long shots. Reconciliation is hard and extremely unsatisfying to the bill’s advocates, and a deal with Snowe is probably too far gone.

- That leaves “ram it through” and “House folds.” I keep bouncing between 2:1 in each direction. So I ended up saying equal chances for each.

Before Tuesday’s election, I predict a 75% chance that there will be a health care law. If Brown wins, I predict a 55% chance of a law and a 45% chance that legislation implodes, with the most likely scenarios being ram it through the Senate before Brown is seated, and the House folding and passing the Senate bill.

Build your own health care legislation decision tree

If you care a lot about this and think my subjective judgments are crazy, then I will help you build your own decision tree. This is called Bayesian analysis. It sounds difficult but it’s not. I will walk you through it, step by step.

You can click on any diagram for a larger view.

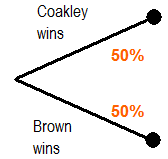

Step 1: What is your projection for the Massachusetts Senate race? You can use polling data, expert analysis, or look at what the market is predicting. I played it safe and called the race a toss-up.

Step 2: I think there’s a difference in the legislative impact of a big Coakley win and a narrow Coakley win. I set the breakpoint at +5. Choose your own breakpoint and set probabilities. Assuming Ms. Coakley wins, what is the chance of a big win vs. a narrow win? I have no idea, so I again chose a 50/50 split.

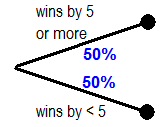

Step 3: Assume Ms. Coakley wins big. What is the chance of a signed law? Everyone seems to think it’s quite high, but is that 90%, 95%, 98%, 100%? I’m guessing 98/2.

Step 4: Assume Ms. Coakley wins a narrow victory. What is the chance of a signed law? It’s lower than under a narrow victory, but how much lower? Leader Reid still has 60 votes, but do nervous Democratic Members bolt because they’re scared of losing reelection? I think a narrow Coakley victory has a fairly big effect, so I drop 98/2 to 90/10.

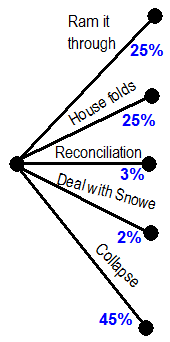

Step 5: This is the hard one. Assume a Brown victory. What path do the Democratic leaders choose, and how likely is collapse? You can review my analysis and the procedural options. The probabilities you assign to these five branches must add up to 100%. Here are my predictions.

Step 6: Put them all together. Multiply the probabilities as you move down each branch of the tree and write the results at the end of each branch. As an example, the “Ram it through” leg on my chart has a 50% X 25% = 12.5% chance of resulting in a law. The “Coakley narrow margin and Democrats bolt” scenario has a 50% X 50% X 10% = 2.5% chance of resulting in no law.

Color results that end in a law in green, and those that do not in red. The result probabilities should add up to 100%. (Click the diagram for a larger view.)

Step 7: Calculate your pre-election probability of a law by adding up all the green results, and your pre-election probability of no law by adding up the red results. Here are my results:

- Law = 74.5%

- No law = 25.5%

I rounded this to get my 75% pre-election prediction of a law.

Step 8: You already know your “Coakley big win” and “Coakley narrow win” probabilities from steps 3 & 4. Calculate your “Brown victory scenario” probabilities like this:

- Law if Brown wins = Add the blue probabilities for the first four scenarios under the Brown wins branch.

- No law if Brown wins = Take the “collapse” probability under the Brown wins branch.

My results if Brown wins are:

- Law = 55%

- No law = 45%

Ta da!

Thanks for playing.

Part 2: Procedural options for health care after a Brown victory

This is the second of three posts on how the Massachusetts special election interacts with health care reform:

- Part 1: What happens to health care legislation if Scott Brown wins Massachusetts?

- Part 2: Procedural options for health care after a Brown victory

- Part 3: My projections for health care reform

Let’s examine the procedural options for Team Obama and the Democratic Congressional leaders, assuming Mr. Brown wins the Massachusetts Senate special election on Tuesday. Each option is painful for the President and Democratic Congressional leaders.

1. Ram it through

This is the easiest procedural path. It’s what they appear to be doing now.

As fast as they can before Senator-elect Brown is certified and sworn in, the White House and Democratic leaders try to do the following:

- Finish the negotiations at the White House.

- Get a CBO score.

- Whip the votes in the House and the Senate, assuming still-seated Massachusetts Sen. Paul Kirk (D) would vote for the bill. Modify the deal as needed to get to 218 + 60.

- Draft the negotiated deal as an amendment to the Senate-passed bill.

- The House substitutes the deal for the text of the Senate-passed bill, passes it with 218 or more votes, and sends it back to the Senate.

- Leader Reid proceeds to the House-passed bill (message) on a majority vote, files cloture on it, and fills the amendment tree to block Republican amendments.

- Two days after filing cloture, Leader Reid gets 60 votes for cloture.

- Republicans take the full 30 hours of post-cloture debate.

- Two days after the cloture vote, a majority of the Senate votes for and passes the bill, sending it to the President for his signature.

Timing matters in the ‘ram it through” option. The variables are:

- How long it takes for leaders to negotiate a preliminary deal;

- How long it takes for them to get CBO scoring to produce an outcome they can sell;

- How long it takes leaders to whip the deal and modify it to get to 218 + 60;

- How long it takes Brown to be certified as the winner; I assume this depends on both the margin of victory, whether the MA Secretary of State tries to slow walk the certification, and whether Leader Reid tried to delay the swearing-in of the winner. Massachusetts law requires the Secretary of State to take “at least ten days” after election day to certify the results.

- Sen. McConnell would have a limited ability to slow things down on the Senate floor.

While I think it’s unlikely, the “ram it through” option could procedurally collapse if the above process moves slowly and Senator-elect Brown is certified and sworn in quickly, denying Leader Reid the 60th vote he would need to execute his part of the strategy. An aggressive Democratic Congressional leadership would have the advantage in an all-out procedural slugfest.

2. House folds

If negotiations drag on until Brown is seated and Kirk is gone, Democrats could throw away the negotiated deal, and the House could simply take up and pass the Senate-passed bill without amendment. This would mean literally not a word could be changed in the Senate-passed bill, because even the smallest change would require sending it back to the Senate. If the House passes the Senate-passed bill, it goes straight to the President. The Senate would never consider the legislation, debate it, or vote on it with their newest Republican member.

A variant involves the House and Senate passing a separate correcting resolution to fix “errors” in the Senate-passed bill. This would, however, provide Senate Republicans with leverage, so I think it’s unlikely.

As snippets of the House-Senate Democratic negotiations leak out of the White House, it is difficult before the election to imagine a post-MA scenario in which the House folds completely. Obviously the House would never choose to do this, but if it was the only way to get a bill to the President.

3. Reconciliation

Again assuming that Sen. Brown has been seated and Leader Reid has at most 59 votes, reconciliation is still technically an option. The House could take the negotiated deal and structure it as a new reconciliation bill, try to pass it through their committees (ugh), and then on the House floor, and then send it to the Senate. Senate committees would again have to act (ugh again), and Leader Reid could then bring the bill to the floor. Reconciliation rules limit floor debate to twenty hours. Floor amendments are in theory limited in scope but not in number, so I imagine Republicans would offer hundreds of amendments to strike pieces of the bill, forcing Democrats to take many tough votes.

This path is really hard and presents multiple opportunities for disaster. The bill would again have to go through House and Senate committee markups, and it’s not even clear that the Senate parliamentarian would consider a new bill in February of 2010 to be a reconciliation bill under the budget resolution passed in 2009. Byrd rule problems would jeopardize the community rating and guaranteed issue provisions and reopen the abortion discussion. And it could only be a five-year bill, which is enough time for all the pain to be felt and for the benefits to just begin. As I said, really hard to execute. This is why you only see Members from the Democratic campaign committees talking about the reconciliation option, and not anyone from the committee that would actually have to do the work.

The key advantage to this option is that Leader Reid would need only 50 votes to pass a reconciliation bill, out of 59 total, since the VP breaks a tie. This would allow a more liberal bill to be enacted, if the procedural hurdles could be overcome.

4. Snowe-storm

The President could negotiate with Senator Snowe (R-ME) to be the 60th vote in the Senate. Stranger things have happened before.

Continue to Part 3: My projections for health care reform, or return to Part 1: What happens to health care legislation if Scott Brown wins Massachusetts?

Part 1: What happens to health care legislation if Scott Brown wins Massachusetts?

This is the first of three posts on how the Massachusetts special election interacts with health care reform:

- Part 1: What happens to health care legislation if Scott Brown wins Massachusetts?

- Part 2: Procedural options for health care after a Brown victory

- Part 3: My projections for health care reform

The Massachusetts Senate race has three potential effects on health care reform:

- Procedural;

- Vote counting; and

- Potential blowback to the procedural response.

If Mr. Brown wins Tuesday, the direct procedural effects are the least important. A 41st vote would give Senate Republicans the power to obstruct but not kill a bill. Even if Brown were to be seated Wednesday, the President would still have procedural options that allow him to enact a law with only Democratic votes. The increased power of Republicans would be indirect: they could make the process path more difficult, requiring the President, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid to work harder to hold Democratic votes. If health care dies because of the Massachusetts election, it will be because nervous Democratic members refuse to support their Leaders’ response, not because Republicans have the votes to prevent a bill from becoming a law.

Democratic leaders now know (finally) that speed is their friend, and they were negotiating non-stop for several days this week. Here are five reasons for them to move quickly:

- Tuesday’s election is entirely downside risk for them.

- The House and Senate Democratic Caucus retreats are next week.

- They would like to pass a bill at least through the House before the State of the Union Address.

- They probably worry that a President’s budget rumored to be “austere” may push away some votes for health care. I expect the budget to be released in the first day or two of February.

- More time means more interest group pressure on Members to draw bright lines.

A Brown victory on Tuesday would still allow Democratic Leaders several procedural options:

- ram it through before Senator-elect Brown replaces interim Senator Kirk;

- throw away the negotiation, and the House passes the Senate-passed bill without amendment;

- pass a new reconciliation bill, either reflecting the text of a negotiated deal or a more liberal agreement; and

- try to bring Senator Snowe back on board for the 60th vote.

The reconciliation option is procedurally challenging. The others are not. If the President wants to push forward in spite of a Brown victory, the Leaders can give him options for doing so. The challenge is not procedural, it is about holding a fragile Democratic caucus together when the procedure is under stress.

The vote counting analysis is not binary. A Brown victory would scare a lot of Democratic Members, but even a narrow Coakley victory will scare some. I think anything less than a five point Coakley win could scare enough House Democrats that House passage could get really difficult. Financial markets react instantly to expectations of future events; elected officials do the same. I imagine there are several Democratic Members of Congress who are already very nervous about their reelection, and increasingly so this weekend as we watch the bluest of States turn purple. A narrow Coakley win should not and will not reassure those members. For them I think it’s the difference in moving from “There’s a risk I might lose reelection if I vote for health care,” to “I’ll probably lose reelection if I vote for health care.” Will Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid still be able to hold their caucuses together?

The impact of a Brown win would be indirect, and it would depend on both the tone and the procedural path adopted by Democratic leaders. If they say, “The Brown victory was not about health care” and charge forward procedurally, that 41st vote will make both the regular order “ram it through” path and the fallback options look procedurally illegitimate no matter when Brown is sworn in.

Democratic leaders risk exacerbating a Brown win by provoking a popular backlash to aggressive or unusual procedural tactics. Rushing a bill through the Senate before Brown is seated could easily be framed as subverting the will of the people, as could the other procedural backup options. Democratic Leaders will have responses about how their procedural paths are within the rules and therefore kosher, but I suspect they will be fighting an uphill battle. The Right and the Tea Partiers would obviously come unglued and be even more motivated for November (is that possible?), but I doubt the Democratic leaders will care. They should care if independents reach the same conclusion, and I expect rank-and-file Democratic Members will be closely watching Tuesday’s independent vote.

TNR’s Jonathan Chait dismisses the electoral impact of procedural hardball: “It’s a process argument of murky merits that will be long forgotten by November.” Further, he argues that

<

blockquote>

I think Mr. Chait is correct from the perspective of the President and Congressional Leaders. They have to worry about the party and their demonstrated ability to lead and deliver policy priorities. Some Members, however, will be more self-centered in their analysis – they might be happy to have health care reform become law, as long as they don’t have to vote for it.

The post-election decisions of three groups become important to passing a bill:

- The President, Speaker Pelosi, and Leader Reid – Do they insist on pressing forward? I think they do. They would not directly bear the electoral risk of enacting a new law. I think they long ago concluded that enacting a new health entitlement is worth losing a few Members.

- Nervous House and Senate Democrats – If a handful of House Members or just one Senator bolt, the bill is in trouble. They are the ones at risk from an aye vote.

- Democratic party elders who don’t work on health care – They may be concerned that ignoring a Brown victory risks creating a November tidal wave that kills their ability to pursue their non-health policy priorities next year. This is why Barney Frank’s comment is so important. Are other senior Democrats convinced by Mr. Chait’s argument, or do they draw new conclusions from Tuesday and decide it is in the Democratic party’s long-term interest to back off?

The only thing I can say for certain is that this will look different Wednesday morning, and again by next weekend after the dust has settled.

Continue to Part 2: Procedural options for health care after a Brown victory, or to Part 3: My projections for health care reform.

Hello, world

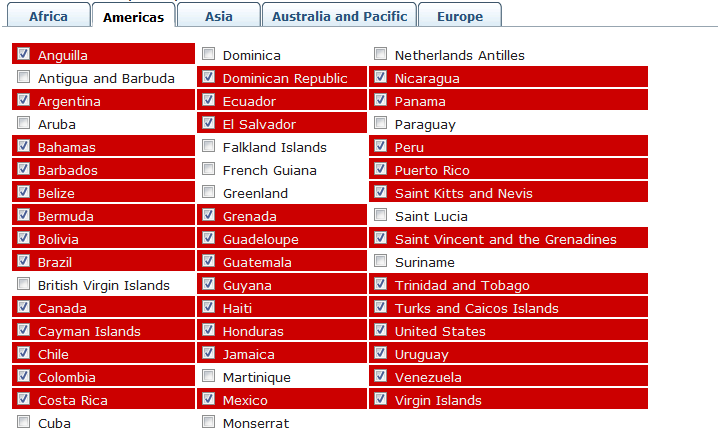

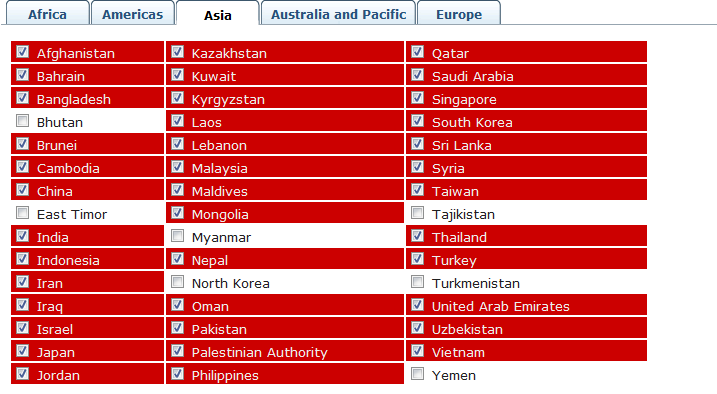

This post is just for fun. Well, fun for me at least.

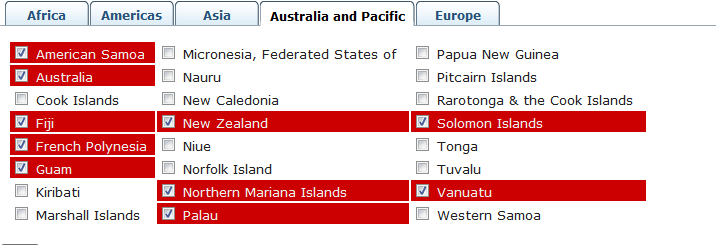

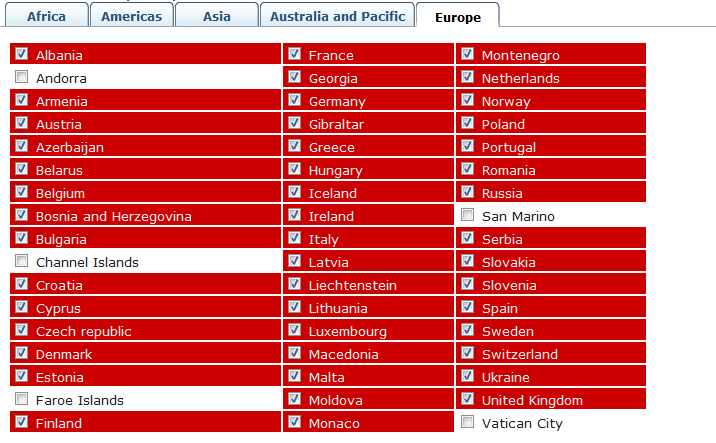

Thanks to the clustrmaps plugin, I can tell how many visits this blog has had from each country. I then used a neat Visited Countries tool by Douwe Osinga that allows you to color countries you have visited to create the map below.

People from 152 countries have visited KeithHennessey.com, 67.5% of all States in the world.

A lot of my international traffic comes courtesy of Greg Mankiw. His economics textbooks are used around the world and he has quite a global following. Any time Greg links to me I get a lot of international visitors.

I guess it shouldn’t be surprising that 86% of my traffic is from the U.S. The next ten top visiting countries, in descending order, are:

- Canada

- China

- United Kingdom

- Australia

- Germany

- Japan

- India

- France

- Spain

- New Zealand

These numbers do not include traffic to the Chinese mirror of KeithHennessey.com. Thanks to Netease for providing it.

Finally, here’s the list of 152 countries that have had someone visit this blog, grouped by continent. I think this is incredibly cool.

To my guests from around the world:

Welcome, thank you for visiting, and I hope you learn a little about American economic policy while you’re here. Please leave me a comment on this post!

The FCIC needs to analyze the failure of Fannie & Freddie

Today was day one of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission hearings. After eight hours of hearings I have a lot of subject matter but little time for writing. So I want to highlight one important point, with more to come over the next few days.

Today the Commission heard from and asked questions of the heads of four large financial institutions that survived: Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Bank of America. Bank of America survived only because of taxpayer assistance. The counterfactual for the other three is unprovable. You can’t prove that GS, JPM, or MS would have failed but for government action, and their leaders cannot prove that they did not need that assistance. That’s the problem with counterfactuals.

I commented at today’s hearing that I am even more interested in learning about the failures than about the survivors. To understand the causes of the financial and economic crisis, I place a higher priority on understanding why Bear Stearns, Lehman, Indy Mac, WaMu, Merrill, and AIG failed, and why BofA, Citi, and others would have failed but for direct government support. In our investigative work the commission needs to spend more time on failure analysis.

At the top of my failure analysis list are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. I think these need to be top priorities for the commission’s statutorily required firm-specific inquiries, for several reasons:

- Each failed spectacularly.

- They are enormous. Their portfolios of retained assets rival the pre-2008 federal debt in magnitude. If “too big” matters, then it applies to these two firms.

- They are central to the flow of mortgage funds. Financial firms are not just “too big to fail,” they are “too big and interconnected to fail.” I cannot think of a financial firm that is more interconnected to certain financial flows than are Fannie and Freddie.

- The expected cost to taxpayers of their failures appears to dwarf that of any other failed financial institution.

- Their failure and cost to taxpayers appear to be ongoing. The cost may be growing.

These are the primary reasons why the Commission needs to prioritize inquiring about the failure of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In addition, a few salient comparisons arose from today’s hearing.

- I asked the four Chairmen/CEOs about the too big to fail question and the perception of a government guarantee for their firms. This is a well-worn debate for the GSEs. We can learn a lot about the TBTF concept from both the pre-failure behavior and the failure of Fannie and Freddie.

- I asked Kyle Bass, one of today’s witnesses on panel #2, to compare the F/F failures with other institutional failures. His answer began with something like, “I don’t know where to begin. There’s just so much.” Bass predicted taxpayer losses from these two firms could exceed $300 billion. Even if it’s “only” $100+ B of lost taxpayer money, that’s an obscene amount.

- We need to better understand the phenomenon of private profit / public risk-bearing. I’m hoping someone can answer a question I asked today: How do the retained portfolios of Fannie & Freddie contribute to their public purposes as stated in their Congressional charters? Were the profits from those portfolios used to advance the GSEs’ affordable housing goals, or to pay dividends and senior managers?

- Many of today’s questions about failed risk management apply to these firms as well. How did firms with apparently large informational advantages make such large failed bets on mortgages?

- Bass had the quote of the day: “Capitalism without bankruptcy is like Christianity without Hell.” If so, then Fannie and Freddie are in Limbo. Their future form and status is uncertain, and the commission can play an important role in this policy debate by understanding and explaining what happened with these firms and why.

- My fellow commissioner Doug Holtz-Eakin made an important point today. Since banks can hold GSE debt (aka “Agencies”) as if it were Treasury debt, you could have bet the health of your bank on the health of these two firms. Rules prevent you from holding all of your bank’s assets in the debt of General Motors, Alcoa, or Home Depot, but you’re allowed to bet the bank on Fannie/Freddie paper. This created an interdependence that I believe in August/September of 2008 required us (the Bush Administration) to preserve 100 cents on the dollar of GSE debt. At the time it appeared that if GSE debt lost any value, the domino effect on much of the global financial system would be devastating. The perception of an implicit government guarantee, combined with government rules and industry practices that encouraged Agency paper to be treated as equivalent to Treasuries, meant that when the GSEs were failing, we thought we had no alternative but to make that guarantee explicit. At the time I hated doing this, but I agreed that there was no acceptable alternative. This is a great example of how a firm’s failure was not just about bad behavior by senior managers, but resulted in part from policy decisions made in Washington.

- Some commissioners spent a lot of their question time today on compensation questions for the four CEOs. Compensation questions are not my top priority, but it seems that any compensation arguments should apply doubly in the case of these two firms that are now wards of the State. Should the senior managers of Fannie & Freddie be compensated based on private-sector or public-sector pay scales? This is a consequence of the Limbo problem.

- The same is true for political involvement. I get a lot of angry emails and comments about how the financial sector tries to influence the political process. FNM and FRE were the textbook cases of an iron triangle political strategy. These firms had comprehensive political strategies to weaken reform legislation and undercut their regulators. The commission needs to understand to what extent their political strategies and business models contributed to the financial crisis.

Today the Commission took a good hard first look at some of the most important financial firms based on Wall Street. Now we need to do the same for the two most important financial firms based in Washington.

My questions for four bank CEOs tomorrow

Thanks to everyone who posted or emailed me questions for the bank CEOs. Let’s continue this transparency experiment.

Here is a working draft of questions I would like to ask the bank CEOs tomorrow. These are still evolving and I won’t get to all of them, but at least they demonstrate my general direction.

- Whether or not your firm faced any risk of failure in 2008, do you think that investors then believed your firm was too big for the government to allow to fail?

- In 2008, did you ever discuss the scenario of your firm failing with any members of your board? Did possible government rescue ever enter into those discussions as a mitigating factor?

- Do you think your firm’s participation in the Capital Purchase Program and the stress tests has strengthened the perception of investors or your board members that the government will, if necessary, prevent your firm from failing?

- Is your firm larger today than it was at the end of 2008?

- Can you measure the impact this perception has on your firm? Has it provided you with a funding advantage relative to some of your smaller competitors?

- Does this perception create what an economist would call moral hazard, an incentive for a firm’s managers to take bigger risks because they know they are partially protected from the downside costs of failure?

- Do you want to have this protection, this put option to the government? Or would you prefer a policy environment in which your firm is subject to a similar failure process as almost any other American firm?

- Obviously no manager wants their firm to fail. What have you done, or what are you doing, to prepare your firm for such a failure scenario?

- What changes should policymakers make to allow large unsuccessful large financial firms to fail?

Explanation

As you can see, I am focusing on the Too Big To Fail (TBTF) concept and how it changed perception and behavior. I am interested in how it affected two groups: managers and investors.

As a matter of public policy, I don’t particularly care how the managers of Caterpillar, Intel, Pfizer or Wal-Mart make decisions. That’s the domain of their boards and their investors.

The same is true for Tiny Bank & Trust or the $20 million Smith Family Hedge Fund – if they make bad decisions, it’s not a public policy issue. The upside and downside risks are internalized within the firm.

What I care about is that in the case of these firms, the government couldn’t let them fail, or at least policymakers perceived there was a big enough chance of disastrous consequences to the financial system that they (we) were not willing to let them fail. In some cases that perception might have been wrong, but if our current policy set remains in place I think it’s highly likely future policymakers in a similar circumstance would come to the same conclusion. Whether or not these firms are too big to actually fail, they are today so big and interconnected that policymakers will not allow them to fail.

My policy ideal is one in which large financial firms are like any other firm in the economy – the firm succeeds or fails on its merits, is subject to a level policy playing field, and, if unsuccessful, fails in a structured fashion.

I want to better understand how far we were (and are) from this ideal, and how we fix that.

Other questions

Some commenters and outside observers are focusing on specific business practices by these firms. These are super-important questions that I believe these firms need to answer, and that the commission needs to address. I anticipate submitting some of them as follow-up questions to the CEOs to be answered in writing after the hearing. (The reality is they will be answered by the firm’s staff, but in most cases I think that’s OK.) I am working today to winnow down this list.

A few public figures have joined the discussion. I have found excellent questions from:

- Andrew Ross Sorkin, Editor of the New York Times’ DealBook column and author of Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System – and Themselves;

- Michael Corkery, lead writer of the Wall Street Journal’s Deal Journal column; and

- Donald Marron, former Council of Economic Advisers Member (and a White House colleague of mine) and former acting Director of the Congressional Budget Office.

In addition, I hope and anticipate a high likelihood that we will invite these firm leaders to testify again. A second round of questions after the staff have done more investigation would be even more productive that I expect from tomorrow’s session. Possibly more importantly, I believe the commission needs to hear from the leaders of large financial firms that failed or nearly failed, including Lehman, Merrill, AIG, IndyMac and WaMu, Citi, and of course Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac .

I want to signal now my primary areas of interest (with the big banks) beyond the TBTF issue, subject to later revision.

- leverage ratios and capital standards;

- reliance on unstable sources of short-term funding for liquidity; and

- informational advantages, especially with respect to clients and credit rating agencies.

You will notice that compensation is not on my list. Yes, I care about it, but not as much as I do about these other topics.

There are plenty of other topics in the financial crisis that interest me. The above list just covers my priorities with respect to the big surviving banks.

Transparency

My outreach has received a little press attention thanks to a few Wall Street Journal and Time posts. I hope this experiment can demonstrate how easy transparency and two-way communication can be.

I debated whether to post my questions. I am telegraphing my shot to the witnesses, but this seems like a small cost, far outweighed by the benefits of getting feedback and provoking public discussion.

One downside is that I am overwhelmed by the volume of input, so I will here extend a thank you to everyone providing help, and apologize for not responding directly to each of the hundreds of emails and comments.

I invite even more input, especially from those with specific related expertise: kbh <dot> fcic <at> gmail <dot> com. I am interested today in help refining the above questions. I am fairly locked into this construct, but am still playing with phrasing and order. Also, I need to ask questions of other panelists – this is a two day hearing. What should I ask AG Holder, SEC Chair Shapiro, and FDIC Chair Bair on Thursday?

The FCIC website is supposed to go live today. I will post Wednesday’s testimony on this blog Wednesday at 9 AM EST, and Thursday’s testimony Thursday at 9 AM.

Finally, for the person who emailed me about being “a targeted individual by the intelligence apparatus and enduring its scorched earth on me professionally, and the CIA also is pimping women for their NSA functionaries,” the NSA usually implants their bugs behind the left ear.

(photo credit: too big to fail by jeffisageek)

More FCIC panelists & more questions

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (henceforth, FCIC) staff has released the details and full witness list for our first substantive hearings.

When:

It’s a two day hearing.

- Wednesday, January 13, 2010: 9:00 a.m. EST

- Thursday, January 14, 2010: 9:00 a.m. EST

Where:

The Ways & Means Committee Room, 1100 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC.

How to watch / listen:

The staff tell us they expect the FCIC website to go live Tuesday of this week, and the hearings to be streamed through the website. That’s their statement, not mine, so please don’t hold me to it. I have nothing to do with the mechanics of the meetings or (potential) broadcast. I don’t know if C-SPAN or any of the business networks will cover it.

The substance

There are five panels over two days. If you read last Wednesday’s post you know about panel 1 on Wednesday. The composition of the other four panels is newly public.

Day 1: Wednesday, January 13

Panel 1: Financial Institution Representatives

- Mr. Lloyd C. Blankfein, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.

- Mr. James Dimon, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, JPMorgan Chase & Company

- Mr. John J. Mack, Chairman of the Board, Morgan Stanley

- Mr. Brian T. Moynihan, Chief Executive Officer and President, Bank of America Corporation

Panel 2: Financial Market Participants

- Mr. Michael Mayo, Managing Director and Financial Services Analyst, Calyon Securities (USA) Inc.

- Mr. J. Kyle Bass, Managing Partner, Hayman Advisors, L.P.

- Mr. Peter J. Solomon, Founder and Chairman, Peter J. Solomon Company

Panel 3: Financial Crisis Impacts on the Economy

- Dr. Mark Zandi, Chief Economist and Co-founder, Moody’s Economy.com

- Dr. Kenneth T. Rosen, Chair, Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics, University of California, Berkeley

- Ms. Julia Gordon, Senior Policy Counsel, Center for Responsible Lending

- C.R. “Rusty” Cloutier, President and Chief Executive Officer, MidSouth Bank, N.A. and Past Chairman of the Independent Community Bankers Association

Day 2: Thursday, January 14

Panel 1: Current Investigations into the Financial Crisis – Federal Officials

- Honorable Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice

- Honorable Lanny A. Breuer, Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice

- Honorable Sheila C. Bair, Chairman, U.S. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

- Honorable Mary L. Schapiro, Chairman, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

Panel 2: Current Investigations into the Financial Crisis – State and Local Officials

- Honorable Lisa Madigan, Attorney General, State of Illinois

- Honorable John W. Suthers, Attorney General, State of Colorado

- Ms. Denise Voigt Crawford, Commissioner, Texas Securities Board and President, North American Securities Administrators Association, Inc.

- Mr. Glenn Theobald, Chief Counsel, Miami-Dade County Police Department, Chairman, Mayor Carlos Alvarez Mortgage Fraud Task Force

Written testimony

I expect each witness will submit written testimony, give oral testimony, and respond to questions. I will do my best to make their written testimony available on this site.

Questions?

While I am providing you with the above information, I did not put these hearings together, nor am I responsible for the mechanics of them. I just show up and participate as one of ten commissioners. So if you have questions or concerns about the structure, participants, or mechanics, please direct them to the Chairman and commission staff. For press inquiries, Tucker Warren is the media contact: twarren@fcic.gov. For everyone else, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until their website is live.

Expanding my request for assistance

Last Thursday I asked for suggestions about questions to ask the bank executives. The feedback has been incredible, both in the comments and in email sent directly to me. Thanks to all who have contributed. The hard part is going to be picking the best 1-3 questions to ask.

I would therefore like to expand that request to cover the other four panels listed above. What do you recommend I ask any of the above-listed panelists about the causes of the financial crisis?

Please post your question in the comments or email it to me: kbh.fcic@gmailcom. Warning: I will impose a stricter comments policy on this post, and I intend to delete comments which stray from the parameters described below. Please take your rants elsewhere, and post or send me only serious questions that meet these criteria.

Please do:

- Tell me at which witness the question is directed.

- Suggest questions that are appropriate for a particular witness.

- Suggest questions that can elicit information that is not otherwise available but should be.

- Suggest hard questions.

Please don’t:

- Suggest questions designed only to attack or embarrass the witnesses. I won’t ask them. My goal is to elicit information and analysis and, if possible, to encourage debate and discussion of what happened and why. I have no problem asking questions that embarrass witnesses or that they want to avoid, but only if it’s the most effective path to serious policy debate. I will leave the demagoguery to others.

- Send me speeches. I am interested in asking questions that solicit useful answers, not in hearing myself talk. If your question begins “Don’t you think …” then you’re on the wrong track.

The Commission’s mission is to “submit on December 15, 2010 to the President and to the Congress a report containing the findings and conclusions of the Commission on the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.”

To repeat: Were supposed to understand and explain the causes of the current financial and economic crisis. That should guide your questions.

Last Thursday I steered questions for the first panel toward the issue of Too Big To Fail with respect to the large financial institutions. While this is one of my major interests, it is not a particular focus of these two-day hearings which are very broadly (too broadly?) framed. This means you should feel free to suggest questions about any element of the financial crisis, as long as you’re focused on the question “what caused X,” where X is some element or effect of the financial crisis.

Hint: The panels that most interest me are the first panels on each day, so I will be examining most closely new questions aimed at the Federal officials who are scheduled to testify Thursday morning.

(photo credit: Global Financial Crisis by sputnik-)

New look

As you can see, I have given the site a facelift. There’s still some work to be done, so don’t be surprised if things keep changing over the next few weeks.

And please let me know of any technical problems you experience, using the “Contact Me” link at the top.

Thanks.

(photo credit: Construction Worker Houston Texas 1 by billjacobus1)