More on the decade of profligacy argument

Last Tuesday I critiqued one of President Obama’s comments in my post “Which is the decade of profligacy?” Mr. Jonathan Chait, Senior Editor of The New Republic, wrote a response which he labeled “the beatdown that was nine years in the making,” and his “smackdown post.” I welcome TNR readers who are new to my blog.

Mr. Chait mistook my intent:

Keith Hennessey is tired of the Obama Administration dragging its predecessor’s name through the mud. Hennessey actually tries to make the argument that Obama’s policies are more profligate than Bush’s.

My intent was instead to correct the logic of and critique the absence of policy solutions from President Obama. I would note that President Bush has remained silent while repeatedly attacked, to allow President Obama the running room he needs to make decisions.

I will respond here to Mr. Chait’s arguments (using his numbering).

1. On the decline in surpluses during the Bush Administration

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “To cast the Administration as victims of a ‘mistake’ requires a staggering level of chutzpah.”

Response 1: If I created the impression of victimization, I apologize. Yes, the tax cut and the post-9/11 spending increased the budget deficit relative to what it otherwise would have been. So did the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the Medicare drug benefit. The Obama Administration suggests, however, that the entire decline in the surplus was the result of policy decisions. That is clearly incorrect. CBO said that 40% of the surplus decline from 2001 to 2002 was the result of forecasting error and a failure to predict the recession. The other 60% was the results of policy choices by President Bush and the Republican Congress, most importantly the tax cut.

Response 2: There was a significant forecasting error that overestimated projected surpluses. Mr. Chait suggests I claimed the Bush Administration was “blindsided.” My argument is a little different. Given that we now know that the January 2001 economic and surplus projections were wrong, it is misleading for Team Obama to use those knowingly incorrect projections to describe the effects of Bush Administration policies.

Response 3: These were not just budget surpluses, they were surplus revenues. When President Bush took office there were budget surpluses largely because taxes far exceeded their historic average. In 2000 taxes were 20.6 percent of GDP, more than two percentage points higher than the historic average. That same year the budget surplus was 2.4 percent of GDP. The budget surpluses existed mostly because the government was taking much more from the private sector than it had historically taken.

Response 4: Three things can be done with a dollar of surplus: return it to the taxpayers, use it to pay down debt, or increase spending on a government program. Team Obama and its allies suggest that if we had not cut taxes and the surpluses had remained in Washington, then all these surplus revenues would have been used to pay down debt. I think it’s far more likely that Congress would have figured out ways to increase government spending (yes, sadly even with Republican Congressional majorities). For me tax cuts vs. debt reduction is a tough call. Tax cuts vs. (an uncertain mix of debt reduction and government spending increases) is a much easier choice.

Response 5: President Bush campaigned on tax relief. He won. He fulfilled his campaign promise and enacted tax relief, in part contributing to smaller surpluses and eventually budget deficits. In doing so, taxes returned to near their historic levels and budget surpluses got smaller as all income taxpayers kept more of the money they earned. Since I focus on spending as the problem, rather than the balance between levels of taxation and deficits, this shift doesn’t concern me as it might some others. I focus on what I think is our primary fiscal challenge: slowing the growth of government spending.

Argument: Mr. Chait writes further, “The Bush Administration furiously and successfully beat back Democrats’ attempts to inculcate caution and modesty about the projected surpluses.”

Response 1: Mr. Chait cites a 2000 convention speech given by President Clinton which effectively proves his point. He also cites his own TNR editorial and a book by Dr. Paul Krugman, neither of whom held any official policy role at the time. It’s important not to confuse the fans and sportscasters with the players on the field. I think other examples of elected Democrats attempting “to inculcate caution and modesty” beyond one sentence in President Clinton’s convention speech would help Mr. Chait make his argument more effectively.

Response 2: Mr. Chait fails to mention that his February 2001 editorial, titled “The Pathetic Party,” was aimed at elected Democrats who agreed with President Bush and supported the tax cuts. 28 House Democrats and 12 Senate Democrats voted for the 2001 tax cuts. If Mr. Chait believes that President Bush’s tax cuts were surplus-destroying bad policy, then his critique applies equally to sitting Democratic Senators Baucus, Carnahan, Feinstein, Johnson, Kohl, Landrieu, Lincoln, Nelson, and many House Democrats as well. (In their defense, they all voted against the much smaller 2003 tax cuts.) Partisan deficit finger-pointing rarely breaks down along clean party lines. Some Democrats support un-offset tax cuts, and (too) many Republicans support un-offset government spending increases.

2. On the cost of the Medicare drug benefit

I wrote that “By the time then-Governor Bush began his Presidential campaign, there was a broad bipartisan Congressional consensus to create a universally subsidized prescription drug benefit in Medicare without offsetting the proposed spending increases.

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “This is misleading bordering on outright false. When Clinton was president, Congress had to operate under pay-as-you-go budget rules, which meant that any new tax cut or entitlement increase needed to be offset by an entitlement cut or tax hike.”

Response: Mr. Chait is almost correct, but not quite. The PAYGO rules from the 1990s did not require these kind of offsets. They merely established a higher voting threshold in the Senate for any legislation which was not offset. The Clinton-era PAYGO rules could be waived if 60 Senators voted to do so, allowing entitlement spending to be increased (or taxes to be cut) without an offset. On July 13, 2000 the Senate defeated a motion to waive the PAYGO (and other budget) rules on an amendment by Senator Bob Graham (D-FL) to create a universally subsidized Medicare drug benefit. Here is Mr. Graham describing his amendment:

Mr. GRAHAM. Mr. President, what we are about is to authorize that $40 billion of the new surplus which has come into the Federal Government and is projected to come over the next 5 years to be dedicated to the prescription medication benefit. This would allow for a total of $80 billion to be committed to this program.

Thus in 2000 Senate Democrats tried to create a Medicare drug benefit without offsetting the cost. They then tried and failed to waive the Clinton-era PAYGO rules. House Republicans passed a bill that year which created a smaller Medicare drug benefit without offsetting the costs. I therefore stand by my statement that “There was a broad bipartisan Congressional consensus to create a universally subsidized prescription drug benefit in Medicare without offsetting the proposed spending increases.” (Senate Republicans, including my boss Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, were not a part of that consensus and did not try to create a Medicare drug benefit that year.)

3. On the Bush tax cuts

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “… Obama’s determination to let

Response: I agree. I never wrote that President Obama was doing exactly what President Bush did on tax cuts, and flagged the difference in my post.

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “It’s true that Obama is keeping in place the tax cuts that benefit people who make under $250,000. But to equate that decision with enacting the tax cuts in the first place is absurd. Both public opinion and the political system have a huge bias toward the status quo. Once the Bush tax cuts were in place, anybody opposing them became a tax hiker.”

Response: This misses my point. I was not trying to equate extending tax cuts with initially enacting them. While they have the same policy effect, I agree that they are politically different.

I was trying to focus on the offset hypocrisy inherent in the President’s argument, not the policy or political aspects of the deficit-increasing policy. Since all the tax cuts are scheduled to expire on December 31st of this year, to “keep in place” that tax relief President Obama must propose legislation to extend the subset of the Bush tax cuts that he favors. President Obama is not proposing to offset that legislation with entitlement spending cuts or other tax increases.

President Obama signed into law what he calls tax cuts in the 2009 stimulus. He proposes to extend some of the Bush-era tax cuts. He is signaling that he will sign a new un-offset jobs bill containing tax cuts. In each case, he is not insisting that the deficit increases resulting from such tax cuts be offset. If he were worried about the need for short-term fiscal stimulus, he could insist on offsets that take effect later in time. And still he attacks his predecessor for enacting tax cuts without offsetting the resulting deficit increases. It seems Team Obama’s rule is “PAYGO for thee but not for me.”

Argument: Mr. Chait explains that I know how politically difficult it would be for President Obama to allow taxes to increase on the middle class.

Response: True. No dispute.

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “Since Bush did cut taxes, restoring those rates in the face of unwavering GOP opposition would be a near-impossible task for Obama.”

Response: Reconciliation can be used to raise taxes with only a simple majority in the Senate, so if Mr. Chait is correct that doing so would be nearly impossible, it is because Congressional Democrats would choose not to do so. Republicans have no formal procedural leverage to block such a bill, even with 41 Senators.

I am happy that it is unpopular to raise taxes. If you believe that future deficits are a problem, then you are obliged to try to do something unpopular: raise taxes or slow the growth of entitlement spending. I prefer the latter. I want President Obama to choose one or both.

4. On the future deficits that President Obama faces

Argument: Mr. Chait writes, “Hennessey doesn’t deny the undeniable reality that this is entirely because Obama inherited a collapsed economy and a structural deficit caused by Bush-era policy changes.”

Response 1: Mr. Chait appears to accept the work of the liberal Center on Budget & Policy Priorities as defining the undeniable reality. While I respect the authors of that particular paper, I do not.

Response 2: I argue that President Obama’s policies will increase future budget deficits. The Obama Administration argues otherwise. This debate focuses on the current policy baseline question I discussed yesterday. Mr. Chait is correct that President Obama inherited an economy in severe recession and a large projected 2009 budget deficit. And yet in January of 2009, CBO projected that budget deficits would decline under current law to about 1 percent of GDP by the end of the decade, and debt held by the public would decline to about 42 percent of GDP. The future deficits we now face are much larger. These deficits are in part a result of the situation when President Obama took office, in part a result of his team misdiagnosing the macroeconomic situation and the policies needed to address it in their first year, and in part a result of policy choices the President is making.

Response 3: Even if I were to grant Team Obama’s characterization of what they inherited, they have the power to propose solutions. With enormous supermajorities in the House and Senate and a reconciliation process, they have the power to enact policies to improve the outcome, even if Republicans don’t play ball. They have so far not done so. I believe that at some point, failing to even propose policy solutions to a problem you argue you inherited makes the problem yours. Inaction is a choice which accrues responsibility over time.

Conclusion

I disagree with Mr. Chait’s characterization of the Bush Administration’s economic policy record and its results. Like two drunks at a bar, we could argue until closing time about whose team is better. This is, however, the wrong debate.

I presume the Obama Administration is highlighting the contrast with its predecessors in part to excuse the deficits in their proposed budget and in part to draw a contrast during a midterm election year. That’s a normal part of the inside-the-Beltway game as it is played by some on both sides of the aisle. I suspect this kind of behavior may contribute to the frustration of many who live outside the Beltway.

It would be far more productive (and maybe even more politically popular) if the Administration focused its attention on prescribing solutions to our policy problems. What is the appropriate short-term balance between budget deficits and fiscal stimulus? How does the President propose we accelerate GDP and job growth? What is an acceptable level of budget deficit in the medium and long run, and how does he propose we get there? Should we raise taxes, slow the growth of entitlement spending, or both?

These are enormous policy questions. The solutions to any one of these questions can, should, and will be fiercely debated. That is a far more productive debate than trying to apportion responsibility for the challenges America faces. To begin that debate, the President needs to propose solutions. He has not yet done so.

Should we care about deficit reduction or deficits?

Budget Director Peter Orszag wrote a blog post last Tuesday titled “A Short History of Deficit Reduction” in which he wrote:

The President’s Budget represents an important step towards fiscal sustainability: it put forward $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction over the next ten years, even excluding savings from the assumed ramp-down in war funding over time. Including these war savings, the deficit reduction proposed in the President’s Budget rises to $2.1 trillion.

This provokes an important question: should we care about how much proposed policy changes reduce future projected budget deficits? Or should we care about the deficits that result after those policy changes are made?

I think this is easiest to explain with an example. We will look at FY 2012, which begins 20 months from now in October 2011.

- Suppose I tell you that if we enact my policies, the deficit in 2012 will be 5.1% of GDP.

- You remember that any number above 3% means that our debt will expand as a share of the economy.

- You know that the average budget deficit since the end of World War II is 1.8% of GDP.

- You know that this 5.1% will be tied for the fifth-largest deficit since the end of World War II.

- You therefore conclude that this is a bad outcome.

- Now suppose I tell you that if we just continued current policies, the deficit in 2012 would be 5.8% of GDP.

- You would conclude that my proposed policies would result in reducing the 2012 deficit from 5.8% to 5.1%. That’s 0.7 percentage points of deficit reduction.

- You would therefore conclude that my policies would make things better than if we just continued current policies.

- I will talk about how my policies would reduce the deficit, and I would emphasize the 0.7 percentage points of deficit reduction that I have proposed.

- Finally, suppose I tell you that if we just continued current law, the deficit in 2012 would be 3.8% of GDP.

- You would conclude that my proposed policies would result in increasing the 2012 deficit from 3.8% to 5.1%. That’s 1.3 percentage points of deficit increases.

- You would therefore conclude that my policies would make things worse than if we just continued current law.

- You could attack me for increasing the deficit, emphasizing the 1.3 percentage points of higher deficits.

What’s the difference between current policies and current law?

- Current law is precisely defined. There is no debate about the 3.8% or 1.3% numbers above in (3).

- Current policy is a more ambiguous definition, and it depends on who is defining what current policies are. The Obama Administration argues that current policies include extending the Bush tax cuts, indexing the AMT, and continuing to allow Medicare physician payments to grow. The Bush Administration included the first of these but not the other two.

- When you measure changes against current policies, you are not “charged” for the deficit increases that result from continuing those policies. Thus when the Obama Administration says “let’s continue to allow Medicare payments to doctors to increase,” they don’t charge themselves for the $371 B of higher spending and higher deficits that this policy would mean relative to current law.

- A current policy baseline therefore allows you to claim credit for more deficit reduction.

Now substitute “President Obama” for “I” above in the example. All three of these conclusions are therefore simultaneously true for President Obama’s budget in 2012:

- If enacted, President Obama’s policies would result in a deficit of 5.1% of GDP. This would tie the fifth-largest deficit since World War II, is far larger than the post-WWII average deficit of 1.8%, and would increase our debt as a share of the economy. This is a bad outcome.

- If enacted, President Obama’s policies would result in 0.7 percentage points of deficit reduction compared to current policies. This is an improvement over current policies.

- If enacted, President Obama’s policies would increase the deficit by 1.3 percentage points compared to current law. This is a deterioration relative to current law.

Most of the public debate you will see about the Obama budget will be about conclusions (2) and (3). The President and his team argue their budget reduces the deficit. CBO and Congressional Republicans will argue that it increases the deficit.

You will find that nobody argues about the 5.1% of GDP number in (1).

Nobody argues about the 1.3% of GDP number in (3).

But there is much debate about the 5.8% and 0.7 percentage points numbers in (2), because there is judgment involved in determining the starting point for this measurement.

Relying on a current policy baseline is difficult because nobody agrees what current policies are. The Bush and Obama Administrations differed on whether continuing to allow Medicare physician payments to grow is current policy or not. These judgment calls make it difficult to trust claims of deficit reduction relative to current policy, because you always have to follow up and ask about the assumptions in the current policy baseline. To be fair, this same critique applies to the Bush Administration for which I worked and the extension of the Bush tax cuts.

At the same time, the debate between (2) and (3) is very inside-the-Beltway. Everyone focuses on the actions they propose to take, and whether those actions make things better or worse. This works particularly well in a zero-sum political debate like we usually have on fiscal policy.

I argue we should instead focus on the deficits that would result from policy changes, and therefore on conclusion (1). I don’t particularly care if President Obama’s proposed policy changes in 2012 increase or reduce the deficit compared to what it otherwise would have been. I care instead that his policies, according to his own numbers, would result in a deficit equal to 5.1% of the economy.

The Administration might respond that I have distorted this example by choosing 2012, when they assume we are still recovering from the recession. Their problem is that the same concept holds true for the entire decade. The President’s budget says that his policies would result in average deficits over the next decade of 4.5% of GDP, and that the smallest deficit in the next decade would be 3.6% of GDP.

Whether the President’s budget represents an improvement or harm isn’t that important to me. Arguing about deficit reduction is something of a distraction. We should instead focus on the deficits that would result from a particular set of policy changes. If the resulting deficits are too big, then we need to make bigger policy changes so that the resulting deficits are acceptable.

Those resulting deficits are too big. We need to do more than the President has proposed.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Pete Souza)

Ten years ago? Seriously?

On Monday when releasing his budget the President said:

The fact is, 10 years ago, we had a budget surplus of more than $200 billion, with projected surpluses stretching out toward the horizon. Yet over the course of the past 10 years, the previous administration and previous Congresses created an expensive new drug program, passed massive tax cuts for the wealthy, and funded two wars without paying for any of it – all of which was compounded by recession and by rising health care costs. As a result, when I first walked through the door, the deficit stood at $1.3 trillion, with projected deficits of $8 trillion over the next decade.

This is a common refrain from the President and his team.

Argument: The previous administration and previous Congresses created an expensive new drug program – without paying for any of it.

- Response 1: Yes, we did. At the time, Congressional Democrats tried and failed to create an even more expensive new drug program without paying for it. (Mr. Obama was not in the Senate at the time.)

- Response 2: This Medicare drug program is ongoing. If the President thinks it is too expensive, then he should propose to make it less expensive. If instead he thinks it should be paid for, then he should propose other spending cuts or tax increases to offset the future costs. Pending health care legislation would instead expand this expensive benefit and pay for the expansion, but would do nothing about paying for the ongoing base costs to which the President is objecting. The past six years of deficit spending from this benefit is beyond President Obama’s control. The future spending is not. He could do this through reconciliation with 51 votes in the Senate.

Argument: The previous Administration and Congresses funded two wars without paying for it.

- Response 1: The Obama Administration is continuing these wars without paying for them, and expanding forces in Afghanistan without paying for that.

- Response 2: Two of those years were with Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. There were legislative attempts to end the Iraq efforts, but none to end the Afghanistan efforts. I don’t remember anyone in the Democratic majority Congress (including then-Senator Obama) making a serious run at cutting other spending or raising other taxes to offset the war costs. Last year Rep. Obey proposed a war tax and was quickly silenced by his colleagues.

Argument: The previous Administration cut taxes for the wealthy without paying for it.

- Response 1: Setting aside the mischaracterization “for the wealthy,” President Obama proposes to extend a significant portion of that tax relief “without paying for it.”

- Response 2: If all the Bush tax cuts are left in place bracket creep will soon cause total federal taxes to once again climb above their historic average of just over 18% of GDP. Repealing these tax cuts would mean the government would be taking far more from the private sector in taxes than it has in the past. I believe taxes are not too low.

- Response 3: Our medium-term and long-term deficit problems are driven by the growth of entitlement spending: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Raising taxes will not slow this spending, it will just buy us a few years of delay and slow economic growth.

Argument: The Bush policies caused a $200 B annual surplus and “projected surpluses stretching out toward the horizon” to turn into deficits.

- Response 1: This argument always relies on one specific forecast which later turned out to be inaccurate. In January 2001 CBO projected a 2002 surplus of $313 B. One year later they projected a 2002 deficit of $21 B. Of the $334 B decline, CBO said 73% was from “economic and technical changes” beyond President Bush’s control. The other 27% was the result of legislation. The impact of policy over time was larger than in 2002 (about 60% over ten years), but it is still incorrect to attribute it all to policy, rather than to a combination of policy and incorrect forecasting.

Argument: As a result of these policies, when President Obama took office, the deficit stood at $1.3 trillion.

- Response 1: The 2009 deficit President Obama inherited was large (CBO says $1.2 trillion rather than $1.3 trillion), but this is principally the result of a drop in revenues resulting from the severe recession beginning in September 2008, and from more than $400 B of projected 2009 spending for bailouts of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the big banks, and other large financial institutions. Before the recession and financial collapse of 2008, annual budget deficits during the Bush Administration averaged 2.0% of GDP (which would be about $290 B in 2009), including the higher spending and lower revenues from the drug benefit, Iraq and Afghanistan, and tax cuts. President Obama is using one horrible year to mischaracterize the other seven.

- Response 2: President Obama does not point out that his first major policy effort was to propose and enact an $862 B stimulus law without paying for it. (CBO has upped their estimate from the previous $787 B figure.) He did inherit a huge deficit, in large part resulting from the recession and bailout costs, and he immediately made it much bigger.

- Response 3: There is nothing the President can do about the past accumulation of debt. He and a majority of the House and Senate can reduce or even eliminate future deficits if they are willing to make hard choices. Even a 41-vote Republican Senate minority lacks the procedural tools to block a deficit reduction reconciliation bill.

Argument: When President Obama took office, he faced projected deficits of $8 trillion over the next decade.

- Response: There is no delicate way for me to say this. The $8 trillion number is made up. In January 2009 CBO projected deficits for the next decade of $3.1 trillion. The President’s first budget played games by redefining the baseline to make the starting point look as bad as possible so that Team Obama could claim their policies would reduce the deficit. Don’t get me wrong — $3.1 trillion of projected deficits is still a huge bad number. At the same time, $4.9 trillion is a lot of gaming.

This debate about the past can continue ad nauseam. At some point I hope it ends, but the President and his team bring it up at every opportunity. It is strange for a President to complain repeatedly about ten-year old policies and then not propose to change them. More importantly, this debate is not relevant to the problems we face today.

Yes, President Obama faced some enormous economic challenges early in his term. His predecessor did as well, even before the crisis of 2008: a bursting tech bubble leading to a recession in 2001, an economic seizure caused by 9/11, corporate governance scandals in 2002, a recession in 2002-2003, the economic uncertainty triggered by invading Iraq (this one was a policy choice), and eventually oil spiking above $100 per barrel.

I think it’s OK for a President to talk about the challenges he and the Nation face. It helps to set reasonable expectations. I think a President should propose solutions to those challenges and describe a brighter future that he hopes to deliver. I think it’s tacky and tiresome for a President to keep bashing his predecessor, especially more than a year after taking office. I acknowledge that my perspective on this point is biased by my professional past.

I also think this refrain weakens President Obama. He is portraying himself as a victim of forces that are beyond his control. A President should want people to focus on him and what he’s going to do, not on a comparison of him with someone else (anyone else). President Obama should want people talking about the Obama Agenda rather than about what happened ten years ago. Ten years ago.

I suspect that many Americans are tired of the blame game, especially more than one year into a new Administration. Whatever your view of President Bush, his policies, and their results, America needs to look forward. We have big challenges ahead of us, and we need to propose, debate, vote on, and then implement solutions.

More than the blame game, this is what concerns me about the President’s economic agenda. The President’s own projections show that his policies will not fix the future problems he identifies. Based entirely on numbers from the President’s just released budget, America will see the following results if all of his policies are implemented as proposed and work as projected:

- an average unemployment rate this year of 10.0 percent;

- an average unemployment rate in 2012 of 8.2 percent;

- a budget deficit this year of 8.3% of GDP;

- a budget deficit that at no point in the next decade dips below 3.6% of GDP;

- debt/GDP increasing from 64% now to 77% in ten years;

- the size of government, measured by both spending and taxes, climbing to historically high shares of GDP;

- three problems identified by the President (I do not necessarily agree that each of these is a problem):

- continuing the expensive Medicare drug program without paying for it;

- continuing the efforts in Iraq and expanding them in Afghanistan without paying for it;

- continuing much of the Bush tax relief without paying for it; and

- not measurably slowing the long-term growth of the major entitlement programs.

These are the results if the President’s policy program is successfully implemented.

I agree with the President that he inherited a tough situation, although I disagree with his explanation of the causes. Our fiscal car is driving toward a cliff. To avoid the cliff, the President might want to turn the wheel left, and I might want to turn right. At the same time, President Obama has the wheel. Complaining about the previous driver won’t prevent us from driving off the cliff. I hope the President will soon stop focusing on the last decade, and instead propose solutions for the next one.

What is the goal of the President’s Fiscal Commission?

The President’s Budget prominently features (on page 146, under Table S-1, the Budget Totals summary table) this language:

FISCAL COMMISSION

The Administration supports the creation of a Fiscal Commission. The Fiscal Commission is charged with identifying policies to improve the fiscal situation in the medium term and to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long run. Specifically, the Commission is charged with balancing the budget excluding interest payments on the debt by 2015. The result is projected to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at an acceptable level once the economy recovers. The magnitude and timing of the policy measures necessary to achieve this goal are subject to considerable uncertainty and will depend on the evolution of the economy. In addition, the Commission will examine policies to meaningfully improve the long-run fiscal outlook, including changes to address the growth of entitlement spending and the gap between the projected revenues and expenditures of the Federal Government.

The President therefore defines the Commission’s short-term job as “balancing the budget excluding interest payments on the debt by 2015.”

This means the President’s goal is to run a budget deficit in 2015 that does not exceed the amount the government will spend on interest in that year. This is not a balanced budget goal. It’s a deficit reduction goal that falls far short of balance. The Administration is using clever language to make it sound like a balanced budget goal.

Now we need to do three things:

- Figure out how much the government will spend on interest in 2015. That is the President’s deficit reduction target for the Commission.

- Compare the target with the deficit that OMB says would result from the President’s policies. Then we know how much more deficit reduction the Commission would need to achieve after enacting the President’s specific proposed policies. We can also compare it to the policies in last year’s budget.

- See what the resulting debt would be, which the Budget says would be “an acceptable level.”

Step 1: How much will the government spend on interest in 2015?

Nothing is easy in budget-world. It turns out there are three different answers to this question. When CBO scores the President’s budget there will be four.

CBO says that interest payments on the debt in 2015 will be $459 Billion. This is CBO’s baseline number, their starting point for analyzing proposed policy changes like the President’s Budget. CBO says that in 2015, $459 B is 2.5% of GDP. (CBO’s Table 1-3)

OMB defines the baseline differently, projecting net interest payments of $586 B in 2015, which OMB thinks is 3.05% of GDP in that year. (OMB’s Table S-3)

The President’s Budget proposes policy changes, of course. OMB thinks those policy changes will trim 2015 deficit payments by $15 B in 2015, to $571 B. That’s 3.0% of GDP. (OMB’s Table S-4)

This allows us to build the following table.

Net Interest Payments

| OMB | CBO | |

| Baseline ($) | $586 B | $459 B |

| Baseline (% of GDP) | 3.05% | 2.5% |

| President’s policies ($) | $571 B | not yet available |

| President’s policies ($) | 3.0% | not yet available |

OMB would of course use the OMB column, and they would assume that the President’s proposed policies would be enacted. So I think they would say the goal of the President’s proposed Fiscal Commission is to reduce the deficit so that by 2015 it does not exceed $571 B, or 3.0% of GDP.

CBO will come up with a different score of the President’s policies in a month or so when they rescore the President’s Budget. For now let’s use $571 B / 3.0% of GDP as the target.

Step 2: How big of a gap would the President’s Commission need to close?

OMB says that the President’s proposed specific policies would result in a 2015 budget deficit of $752 B, or 3.9% of GDP. Subtracting, this means the Commission would need to close a $181 B deficit gap in 2015, or 0.9% of GDP.

For comparison:

- Built into his specific policy proposals to get to a 3.9% deficit in 2015, the President proposes increasing taxes on those with incomes above $200K (single) / $250K (family). Those proposals would reduce the budget deficit by raising taxes $97 B in 2015.

- CBO says the new subsidies in the Senate-passed health bill would increase the deficit $74 B in 2015.

The interesting part is that the specific policies in his last year’s budget would have met the goal President Obama now proposes to establish for the Fiscal Commission. One year ago the President said his policies would result in a 2.9% deficit ($528 B) in 2015 (Table S-1), which would meet the President’s new target. In other words, the goal of the new Fiscal Commission is to propose additional deficit-reducing policy changes to close the additional deficit gap opened between last year’s Obama budget and this year’s Obama budget. Some of this gap is the result of a weaker economy, and the rest is because the President is proposing more spending than he proposed last year.

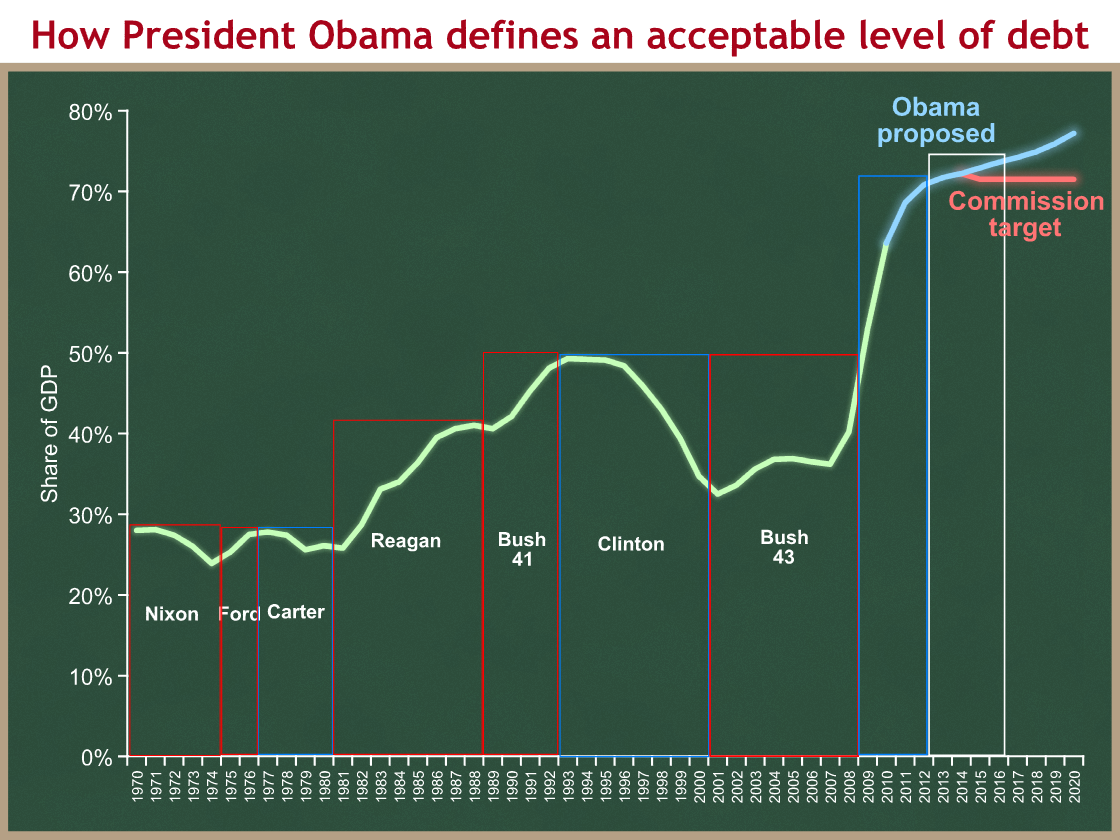

Step 3: Calculate what the President defines to be an “acceptable level” of debt

We now know that the President’s Budget says that if the budget deficit is reduced to 3.0% by 2015 this will be “projected to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at an acceptable level once the economy recovers.” I agree that this deficit level would stabilize debt-to-GDP. Is it “an acceptable level?”

The President’s Budget tells us that his specific policies would result in a debt-to-GDP ratio of 72.9% in 2015, with a 3.9% deficit in that year, 0.9 percentage points short of the Commission’s target. I presume that a Commission would phase their changes in over the next five years, resulting in smaller deficits than those proposed by the President between now and 2015. Eyeballing Table S-1, the President is defining 71-72% of GDP as an acceptable level of debt. I’ll be pick the midpoint and assume a successful Commission stabilizes debt-to-GDP at 71.5%. The Budget creates a little fudge room this with “The magnitude and timing of the policy measures necessary to achieve this goal are subject to considerable uncertainty and will depend on the evolution of the economy.”

Debt-to-GDP last exceeded 70% in 1950 as we were paying off the debt from World War II. We are in 2010 already at about 64%.

Conclusions

- While the President and his team are using the phrase “balanced budget” in their short-term goal for the Fiscal Commission, the actual goal is to reduce the budget deficit to no more than 3.0% by 2015.

- That is a very weak fiscal policy goal, resulting only in stabilizing debt as a percentage of the economy.

- For comparison, President Bush’s budget deficits over eight years averaged 2.0% of GDP, or 2.7% if you assign the TARP to his tenure.

- The specific policies proposed by the President fall 0.9 percentage points short of the Commission’s goal in 2015, or $181 B in that year. This is the gap the Fiscal Commission would need to close.

- This gap has opened since President Obama’s budget from one year ago, which would have met the new target by proposing a 2.9% deficit in 2015. A weaker economy and new proposed spending increases have opened an additional gap that the President proposes to assign to a Commission to close.

- Debt held by the public now equals about 64% of the economy. The President’s specific proposed policies would, according to OMB scoring, allow that to increase to 77% by the end of the decade. The President says the Commission should propose policies to stabilize debt at about 71-72% of the economy and defines this level as “acceptable.” Debt-to-GDP last exceeded 70% in 1950 as we were paying off the debt from World War II.

- The President does not commit himself to proposing the policies recommended by the Commission. The Commission is charged only with “identifying policies to improve the fiscal situation.” The President is still retaining the right to ignore those recommendations, come up with different ones, or redefine his goal after the Commission has reported.

- The long-term goals of the Commission are imprecisely defined: “to achieve fiscal sustainability over the long run … to meaningfully improve the long-run fiscal outlook.” The long run is an even bigger challenge than deficit reduction over the next five years.

Which is the decade of profligacy?

President Obama released his budget proposal yesterday in the Grand Foyer of the White House. He said:

Good morning, everybody. This morning, I sent a budget to Congress for the coming year. It’s a budget that reflects the serious challenges facing the country. We’re at war. Our economy has lost 7 million jobs over the last two years. And our government is deeply in debt after what can only be described as a decade of profligacy.

The fact is, 10 years ago, we had a budget surplus of more than $200 billion, with projected surpluses stretching out toward the horizon. Yet over the course of the past 10 years, the previous administration and previous Congresses created an expensive new drug program, passed massive tax cuts for the wealthy, and funded two wars without paying for any of it – all of which was compounded by recession and by rising health care costs. As a result, when I first walked through the door, the deficit stood at $1.3 trillion, with projected deficits of $8 trillion over the next decade.

I will set aside the question of the propriety and political wisdom of continuing to attack one’s predecessor more than one year after taking office. I will instead focus on the substance of President Obama’s argument, and in particular his claim of a “decade of profligacy.”

Medicare benefits and tax cuts

It is true that 10 years ago we had a budget surplus of more than $200 billion, and that CBO projected surpluses “stretching out toward the horizon.” When CBO built its budget baseline for 2001, they had not yet accounted for the bursting of the late 90s tech stock market bubble and the effect it would have on federal revenues. Like families, businesses, and investors, CBO made a mistake: they projected future revenue growth that was never going to occur. Critics of the Bush Administration hinge their comparative argument on this single mistaken budget projection which in hindsight analysts from both parties acknowledge was wildly inaccurate.

It is also true that President Bush proposed, and in 2003 the Congress passed and President Bush signed into law, a Medicare drug benefit that was not offset by other spending cuts or tax increases. It is true that this benefit significantly increased the already large unfunded liabilities of Medicare.

What the Democratic critics fail to mention is that the Democratic alternative proposal cost significantly more than the Bush proposal and the enacted law. (This predates Mr. Obama’s time in the Senate.)

What Republican critics fails to mention is that in the late 1990s a Republican-majority House of Representatives passed a Medicare drug benefit without offsetting the proposed spending increases. Senate Republicans offered their own version on the Senate floor, which again was smaller than the Democratic alternative. By the time then-Governor Bush began his Presidential campaign, there was a broad bipartisan Congressional consensus to create a universally subsidized prescription drug benefit in Medicare without offsetting the proposed spending increases. Bush joined that consensus and enacted it into law. Fiscal conservatives should direct their anger principally at House and Senate Republicans of the late 90s. (I worked in the Senate then, so I get blamed either way.)

It is true that President Bush proposed, and in 2001 and 2003 the Congress passed and President Bush signed into law significant tax cuts, and that those tax cuts were not offset by spending cuts or tax increases. If President Obama believes that enacting these tax cuts without offsetting their deficit impact was profligate, then why is he proposing to do the same thing? His budget proposes to change the law to extend all of the Bush tax cuts except those Team Obama mislabels as “for the rich.” He is not proposing offsets for those tax cuts he would extend. It is inconsistent to argue that Bush was irresponsible when he did it, and that Obama is responsible when he does the same thing.

Given my concessions, it must be true that the 00s were a decade of profligacy, and that President Obama’s policies will “restore fiscal discipline in Washington.” Right?

Comparison

Let us examine the results of these so-called “profligate” policies during the Bush Administration, and let’s compare them to the deficits proposed by President Obama. I will compare eight-year Presidential terms rather than decades. In doing so I will assume that President Obama gets a second term, and that the budget he proposed yesterday is enacted exactly as proposed.

When doing this comparison one has to struggle with how to treat fiscal year 2009, which began October 1, 2008 and ended September 30, 2009. A traditional comparison would assign budgets for FY 2001 through FY 2008 to President Bush, and for FY 2009 through FY 2017 to President Obama, since usually the bulk of the laws signed in FY 2009 would be signed by President Obama.

But this would assign all the “blame” (deficit impact) of TARP to President Obama. I am therefore going to calculate deficits for President Bush including FY 2009, as those deficits stood on January 20, 2009 when he left office. In doing so, I am assuming the overwhelming majority of the TARP spending and their deficit “blame” to President Bush, even though he committed only half the $700 B TARP. In other words, I am skewing my analysis to be as generous as possible to President Obama in the comparison with President Bush. (Update: See below for a caveat on the light blue Obama bar, which also includes all of 2009.)

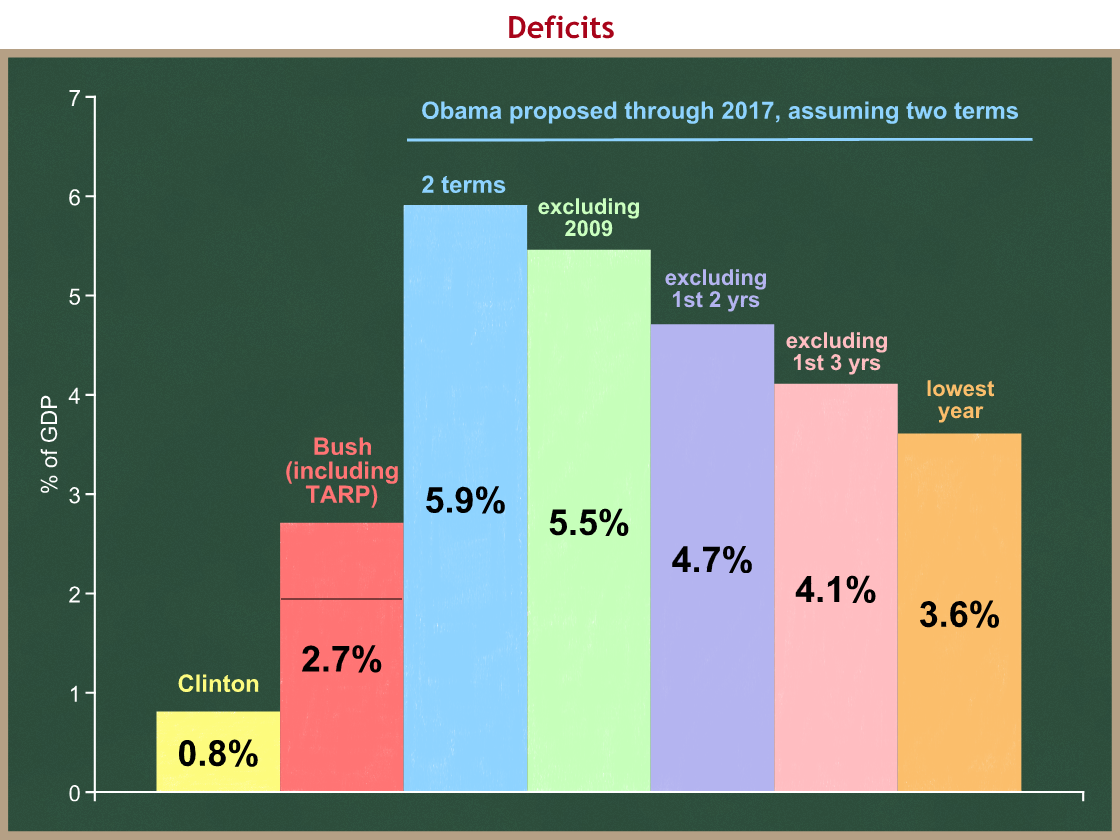

Here are the average budget deficits measured as a percent of GDP. As always, click on any graph to see a larger version.

You can see that budget deficits during President Clinton’s eight years averaged 0.8 percent of GDP. Clinton folks will tell you this is because of his brilliant policies, and in particular the 1993 budget law. I think most of it is the result of tech bubble-induced higher capital gains revenues causing total taxes to surge to record levels. We can have that debate another time.

If I measure President Bush for the nine year period 2001-2009, thus assigning almost all TARP spending to his Presidency, I get an average budget deficit of 2.7% of GDP. (Historical umbers are from OMB’s historical tables. Obama numbers are from Table S-1 in his new budget.) In calculating this nine year average I am adding the horrible FY 2009 into the Bush average, using CBO’s projection for the FY 2009 deficit of 8.3% when President Bush left office in January 2009. Bush therefore gets the deficit hit for most of the TARP, but Obama gets the hit for his stimulus law and the further economic deterioration when he was in office, both of which pushed the actual 2009 deficit to 9.9% of GDP.

You can see a black line within the Bush column. That’s at 2.0%, the average Bush deficit for the eight year period of 2001-2008.

Now let’s turn to President Obama. Remember, we are measuring his average budget deficit through FY 2017, assuming he stays in office for two terms and his new budget is enacted as proposed. I am also being generous by using OMB’s scoring of the President’s budget. CBO is always more pessimistic and would make the Obama numbers look worse.

President Obama’s proposed deficits over the eight-year period FY 2009-2017 are 5.9% of GDP, the light blue bar. That’s more than twice as large as the Bush nine year 2.7% average, and almost three times as large as the Bush eight year 2.0% average. Update: This calculation assumes the full 9.9% FY 2009 deficit in the average, thus it includes the TARP spending and in a sense overlaps with the Bush red bar. The TARP money is being counted with each of them. The next three bars “solve” this problem by excluding all of 2009 (including TARP and stimulus) from the Obama average.

I can imagine someone replying that it’s not fair to blame President Obama for the big deficits we are running as we recover from a severe recession. The next three bars therefore exclude the first one, two, and three years of an assumed eight year Presidency. Surely no one can argue that President Obama should not be held responsible for the budget deficits in years four through eight!

You can see that each of these comparisons, which allow you to “not count” the recovery years in the average for Obama, still result in average budget deficits that far exceed even the worst portrayal of the Bush Administration’s average.

In fact, the smallest annual deficit proposed by President Obama is 3.6% of GDP, in 2018 and 2019, the two years after his second term would end. The lowest during his hypothetical eight years would be 3.7% in 2017 and 2018. The lowest proposed budget deficits in a hypothetical “Obama decade” would exceed the Bush average budget deficit, even if we assign most of the TARP spending to Bush.

This leaves an open question: Which is the decade of profligacy?

The President’s bigger budget

The President proposed his budget today. This is the budget for federal fiscal year 2011, which begins October 1 of this year.

Most people in Washington will focus on (1) the effects of the proposed budget on the deficit and (2) what the budget proposes for specific policies they happen to care about.

I will focus on the size of the proposed budget relative to the rest of the economy. The deficit is an important but incomplete measure of this. It’s important to remember that every dollar not spent by the government is a dollar that can be spent by individuals, families, and firms. We should care not just about the difference between spending and taxes, but also on how big government is relative to the private sector.

Throughout this post I will describe things as a share of the economy (% of GDP). This is a useful way to compare budgets across time but it is biased in favor of bigger government. There is nothing that says that because the economy gets bigger that the government must grow along with it. I’d like to do these presentations in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars to eliminate this bias, but it would make my analysis difficult to compare with almost everyone else’s. For now I won’t fight this and will just use % of GDP.

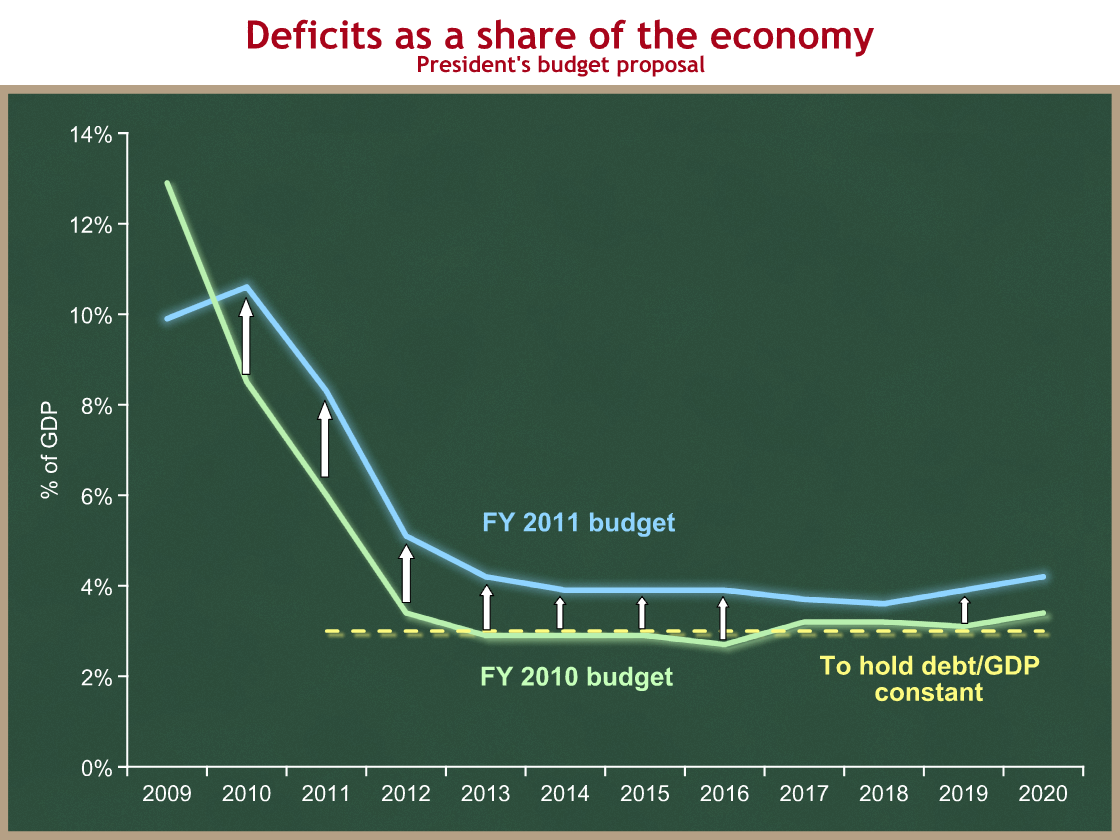

Deficits

Let’s begin with the deficit. As always, click on any image to see a bigger version.

The green line shows deficits as proposed by President Obama last year. The blue line shows deficits as proposed by President Obama this year. The dotted yellow line shows the deficit consistent with holding federal debt (as a share of GDP) constant. If deficits are above this dotted yellow line, then our debt burden relative to our economy’s ability to pay for it will increase. If deficits are below that line, our debt burden will decline relative to the economy. (I’m oversimplifying a bit – the dotted yellow line should actually slope gradually upward depending on what happens to debt in the intervening years.) For now this maximum is 3.0% of GDP.

We can draw five important conclusions from this graph:

- At 8.3% of GDP, the proposed budget deficit for 2011 is still extremely high.

- President Obama is proposing larger budget deficits than he did last year.

- For 2011, the most relevant year of this proposal, the President is proposing a budget deficit that is 2.3 percentage points higher than he did last year (8.3% vs. 6.0%).

- Using his own numbers, the President’s proposed budget deficits will cause debt as a share of the economy to increase.

- Under the President’s proposal, budget deficits begin to increase as a share of the economy beginning in 2018.

Adding further detail to (4), the President’s own figures show deficits averaging 5.1% of GDP over the next 5 years, and 4.5% of GDP over the next ten years. They further show debt held by the public increasing from 63.6% of GDP this year to 77.2% of GDP ten years from now. I think it’s a safe assumption that CBO’s rescore of the President’s budget will be even worse.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, short-run deficit reduction is contractionary. Reducing the budget deficit toward manageable levels is necessary from a federal fiscal standpoint, but it reduces short-term economic growth. This is the Administration’s core short-term economic policy challenge, the tradeoff between fiscal stimulus and deficit reduction over the next 2-3 years.

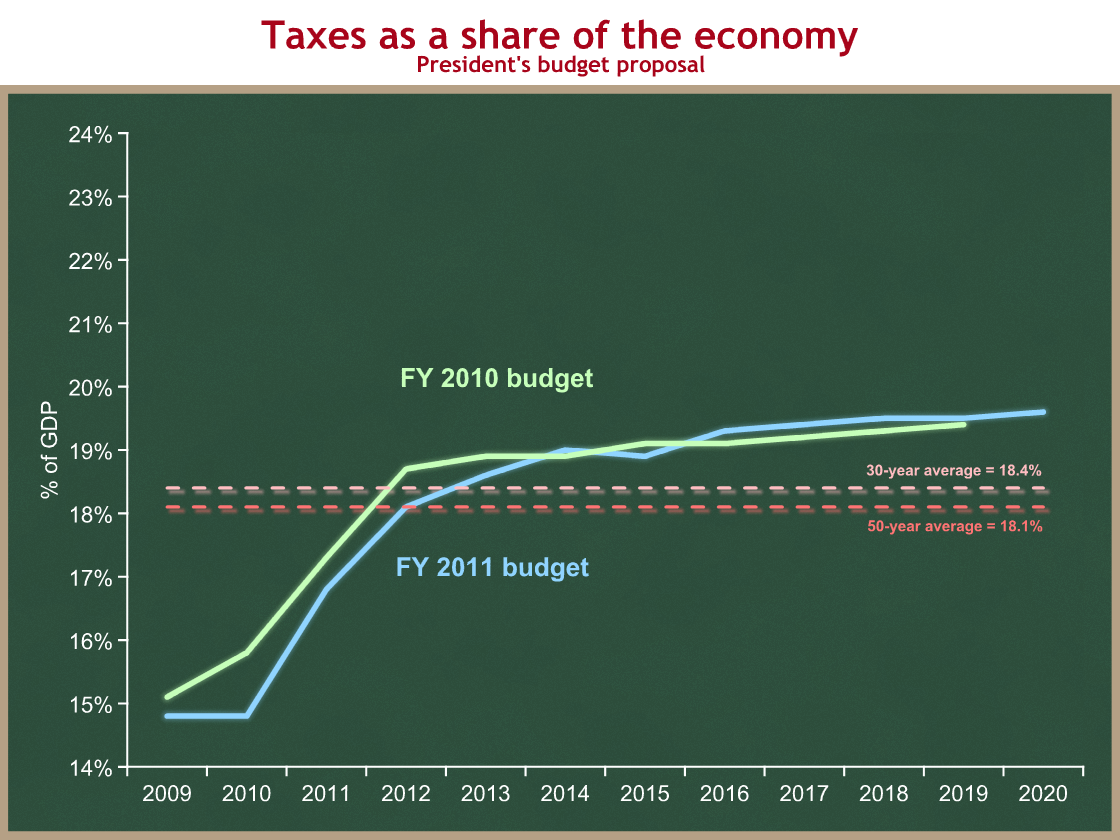

Taxes

The green line shows total revenues proposed by the President last year, and the blue line shows this year’s proposal. The dotted pink and red lines show historic averages of the past 30 and 50 years.

You can see that taxes were really low when the President took office, a consequence of the severe recession. The big jump from 2010 to 2012 is a result of several factors all pushing taxes higher:

- as the recession ends, revenues will recover as a share of the economy;

- President Obama proposes to allow some of the Bush tax cuts to expire on December 31 of this year;

- He is proposing some other tax increases as well;

- The tax code has features that build in tax increases over time. The most important is known as bracket creep.

We can draw two conclusions from this graph:

- Taxes are low now, but are scheduled to increase to above historic averages.

- The President is proposing slightly lower revenues over the next few years than he proposed last year, but essentially no difference in the long run.

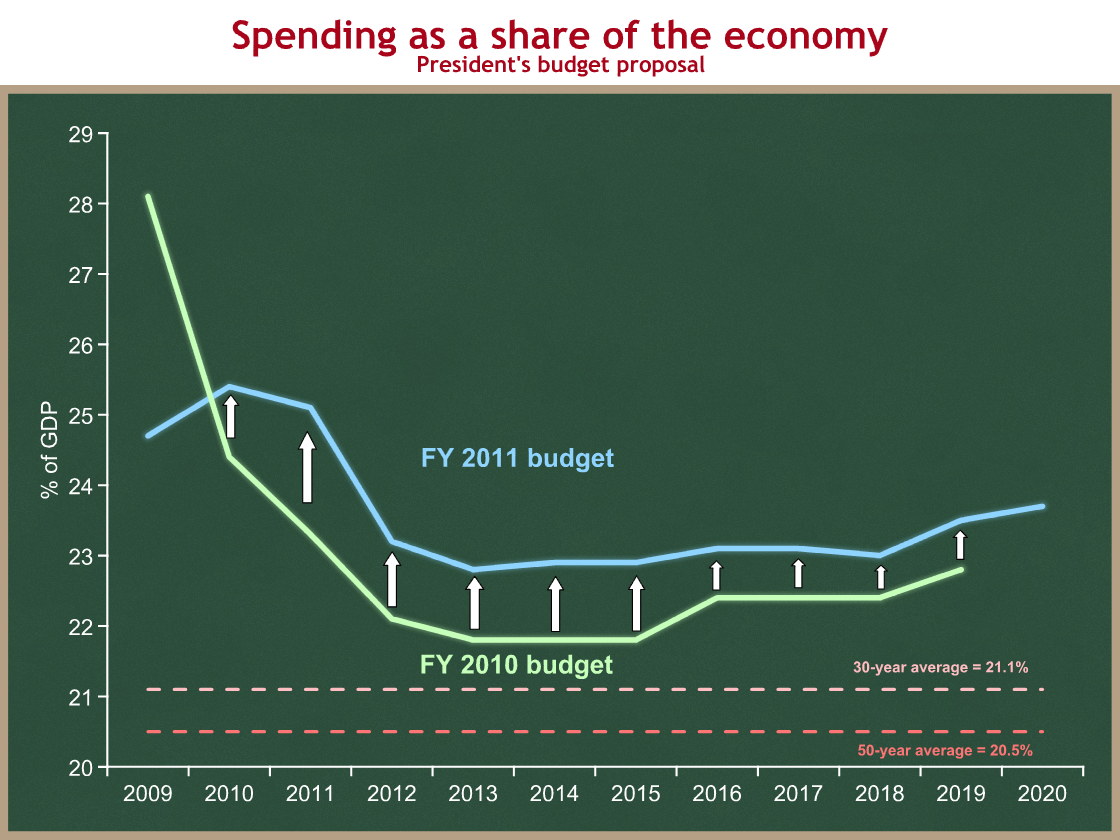

Spending

I saved the most important graph for last. Every dollar spent by the government must be either taken from someone in the private sector (taxes) or borrowed from the private sector (deficits).

Again, green is last year’s proposal, blue is this year’s proposal, and dotted pink (30-years) and red (50-years) are historic averages.

We can conclude:

- The President is proposing significantly more spending than he proposed last year: 1.8% of GDP more in 2011, and roughly 1 percentage point more each year over time.

- Spending is and will continue to be way above historic averages.

At its lowest point in the next decade federal spending would still be 1.7 percentage points above the 30-year historic average. Over the next decade, President Obama proposes spending be 12% higher as a share of the economy than it has averaged over the past three decades.

Remember that fiscal policy is not just about the budget deficit, the difference between spending and taxes. It’s also about the size of government: how much is the government spending, and therefore taking from the private sector?

What does it mean to focus on jobs?

The conventional Beltway logic is that the President used his State of the Union Address to “pivot to focus on job creation.” We have been told for a week or two that job creation is policy priority #1.

The Administration’s original game plan was to have health care reform finished or nearly finished by now. The President would begin 2010 signing health care reform into law and would spend the bulk of the year working on reducing the high unemployment rate.

Scott Brown’s election and the subsequent collapse of health care reform have fouled up that sequence. Nevertheless, Wednesday night the President “pivoted to focus on jobs.”

That is why jobs must be our number one focus in 2010, and that is why I am calling for a new jobs bill tonight.

I have a simple question: What does it mean to focus on jobs?

I would presume that it means the President would propose new policy changes that are designed to significantly increase employment, and fairly quickly.

Reviewing where we stand today:

- The unemployment rate is 10.0%, twice my rule-of-thumb full employment rate of 5.0%. (Others might use as high as 5.5% for full employment. Either way we face a huge employment gap.)

- That measure understates the number of people who would like to work but don’t have a job, because many have stopped looking. They are not counted in the 10% number.

- About 2.7 million fewer people are employed today than one year ago, and about 7.2 million fewer people than at the beginning of the recession in December 2007. Since the labor force grows along with population, we would need more than 7.2 million new jobs to return to full employment today.

- The change in both the number of people working and the unemployment rate are bouncing around zero: a net 85,000 jobs were lost in December, and the rate stayed constant.

- Economists are divided about whether the employment situation:

- has bottomed out and will soon begin to steadily but gradually improve;

- has bottomed out and will soon begin to improve, but will tip back downward in the second half of this year as stimulus spending tapers off; or

- is still declining and will continue to decline before things turn around.

- CBO’s recently released economic and budget baseline projects the unemployment rate will be 10.0% in the fourth quarter of this year, and 9.1% in the fourth quarter of 2011. CBO projects the rate will not drop below 8 percent until 2012. Those are unsurprising but dismal projections.

The President’s proposal and the new focus

Last December the President proposed a new “jobs package.” Last night he added two policies to that package:

- “take $30 billion of the money Wall Street banks have repaid and use it to help community banks give small businesses the credit they need to stay afloat;” and

- a new $5,000 “Small Business Jobs and Wages” tax credit for every net new employee they employ in 2010

Everything else in the President’s proposed jobs bill had already been proposed about six weeks ago.

Q1: What, then, is the new focus?

A: Two policies, and a reprioritization of legislative goals, with this bill as the new top priority.

I think there is an extremely high likelihood that this reprioritization will result in a signed law soon (I will guess within 4-6 weeks.) The House has already passed a bill, and the President called on the Senate to take this up first. The President’s State of the Union address and this signal to Congress will therefore have a real legislative effect.

Q2: How much would the President’s new proposal increase employment?

A: Assuming I’m reading CBO correctly, the President’s new “Small Business Jobs and Wages” tax credit would increase net employment in 2010 by less than 300,000 new jobs, and possibly much less. The employment effects of the other components are difficult to estimate but almost certainly are much smaller than the impact of the tax credit. Those are very small numbers compared to the size of the employment gap.

Bang for the buck

Anticipating this policy debate, two weeks ago CBO published an interesting report, Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in 2010 and 2011. They have a great table (Table 1 on page 18) that shows their estimates for the GDP and employment effects of various job creation policies. One policy closely matches the President’s new tax credit, and the White House fact sheet highlights the study:

The Congressional Budget Office recently identified this type of job creation tax cut as the most effective way to help accelerate job growth of all the policy options it evaluated.

The White House fact sheet leaves out the numbers. Here they are:

- CBO estimates that for each million dollars of budgetary cost for this kind of tax credit, full-time employment in 2010 will increase by five to nine years. I’ll explain the difference between increased years of employment and increased jobs in a moment. That works out to $111,000 to $200,000 of taxpayer money (or deficit increase) per new employment-year, and more than that range per new job created this year.

- Over the two-year period 2010-2011, CBO says that for each million dollars of budgetary cost for this kind of tax credit, full-time employment will increase by eight to eighteen years.

- The White House fact sheet says the budget impact of the President’s new tax credit proposal will have a budgetary cost of $33 billion.

My back-of-the-envelope calculation using these numbers suggests that the President’s new Small Business Jobs and Wages credit will increase full-time employment in 2010 by 165,000 – 297,000 years. By 2011, it will increase full-time employment by 264,000 – 594,000 years. But the number of jobs created will be smaller, because some of these additional employment years will be captured by longer hours for existing workers who are working historically short work weeks. Employers tend to make underworked existing employees work longer hours before they hire new workers.

If enacted quickly, the President’s new Small Business Jobs and Wages tax credit proposal will therefore create fewer (and maybe far fewer) than 165,000 – 297,000 jobs this year. For comparison, remember that the U.S. economy has lost 2.7 million jobs since a year ago, and 7.2 million jobs since the beginning of the recession in December 2007. 297,000 is 4.1% of 7.2 million, so you’re talking about a policy change that at best would restore fewer than 1 out of 25 jobs lost since the recession began.

Now for the bigger problem: the White House fact sheet is correct. CBO says this is the job creation policy with the greatest job creation bang per deficit buck. Other policies are less efficient. So while the total 2010 jobs impact of the President’s full proposal will be larger than just the impact of this new credit proposal, it’s still going to take only a tiny bite out of our employment problem, and the other components will have an even smaller effect than this core element.

I am not comfortable extending my back-of-the-envelope calculation to the President’s full proposal, but someone in Congress should ask CBO to apply their methodology to the President’s full package. Members of Congress should understand not just the policies they are voting on, but the projected quantitative impacts of those policies on employment, GDP growth, and budget deficits. The numbers matter.

Expected outcomes

CBO’s new baseline projects that, without new policy, the unemployment rate in the politically significant fourth quarter of this year will be where it is now: 10.0 percent. Economically that’s terrible but not unexpected, given the depth of the recession. Politically it’s disastrous for Democrats because it suggests the employment picture will not improve this year. Further, CBO projects the unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of 2011 will be 9.1%. As both a policy and political matter, this explains why the President and Members of Congress are desperate to do something, anything. Like a panicked Homer Simpson trying to prevent a nuclear meltdown, Congress is about to start wildly pressing buttons and turning dials on their control panel, almost all of which will have no beneficial effect.

A couple of weeks ago economist Dr. Mark Zandi testified before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission at its first substantive hearing. I took that opportunity to ask him about fiscal stimulus and job creation. I asked him what his baseline forecast for the unemployment rate was at the end of this year. He said about 10.5%, half a percentage point higher than it is now, and half a percentage point that CBO now projects.

Dr. Zandi advocates a new fiscal stimulus package (which apparently we are now calling a jobs bill.) I asked him to imagine that Congress enacted the best job-creating fiscal stimulus legislation he could reasonably expect. How big would such a package be, and what effect would it have on the unemployment rate?

Dr. Zandi hypothesized enactment of a new $200 B law, spread out over 2010 and 2011. He stressed that the primary economic benefit would be to reduce the chance of a double-dip recession as the first stimulus tapers off later this year. When I pressed him for what he thought the resulting unemployment rate might be, he said 10 percent.

So this oft-quoted economist is estimating that a new job-creation stimulus law would increase the deficit by another $200 B, reduce the risk of a double-dip recession, and reduce the future unemployment rate by only about half a percentage point.

There is a policy tradeoff between employment impact and deficit increase, centered around the relative inefficiency of policy changes at increasing employment. There is no analytically “right” amount of federal resources to commit to new fiscal stimulus. Dr. Krugman has long been arguing for another very large stimulus, prioritizing GDP growth and reducing unemployment over an admittedly large further increase in the budget deficit. Dr. Zandi is making a similar argument, but in a smaller numeric range. President Obama is doing the same, but in an even smaller range than the Zandi $200 B number (I think). I expect some Congressional Republicans will argue that we should not increase the budget deficit with policies that are so inefficient at creating jobs. Well-intentioned people can disagree on this policy tradeoff.

Jobs policy, politics, and messaging

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. – George Santayana, The Life of Reason Vol. I

The hard policy question is whether in the current economic environment you do something that is directionally correct but trivially small, and at the same time is very expensive. Everyone’s political instinct is that doing something is better than doing nothing. What makes it hard is that this something is expensive and we have a huge budget deficit. Action has a small policy benefit and a medium-sized cost. Inaction has no policy benefit and no policy cost, but a big political downside because you look like you don’t care about the problem.

By saying that jobs are “our number one focus in 2010,” and by having a specific legislative proposal that is likely to become law, the President is once again raising expectations that he can deliver improved economic results. Just over one year ago now-CEA Chair Christina Romer and now-VP economic advisor Jared Bernstein projected that enactment of a stimulus proposal would reduce the unemployment rate so that it would peak at 8 percent. This optimistic projection helped sell the stimulus and later proved to be wildly inaccurate.

The risk to the President is that he repeats this political and communications mistake, whatever your view on the policy. By making jobs his number one focus, he raises expectations in the Nation and in the Congress that policy changes can quickly make things much better. They cannot unless you’re willing to do far more aggressive policy than the President has proposed. Doing so would have somewhat larger GDP growth and employment benefits, and enormous deficit costs.

At the same time, to lower expectations he must explain that his policy proposal to focus on jobs will have only a minimal benefit, and will result in a still dark employment picture for the foreseeable future. That’s a pessimistic message that could undercut his ability to enact his proposal. He is boxed in by a painful policy reality.

The President and his Congressional allies are courting political disaster by raising expectations that their new “number one focus on jobs” will result in a measurably improved employment picture as we approach Election Day. They better start lowering expectations fast, because they are setting themselves up (again) for political failure.

(photo credit: White House photographer Pete Souza)

Why you can’t do just the health insurance reforms

Some in the House are floating the idea of splitting up either the House or Senate health bills into component parts and passing them individually. Some may see this as a way to get partial substantive wins. Others may hope the component bills die in the Senate so they can blame Republicans in November. This strategy does not work substantively.

There is a health insurance reform that could be done individually. The tax code and health insurance rules could be changed to make health insurance portable. If you change jobs but don’t move, you almost certainly keep your car insurance. We don’t even think of it as “taking your car insurance with you,” because your employer is not involved in this purchase. We could do the same for health insurance with some fairly minor changes to law, so that if you switch jobs (or just leave your current job) you could keep your health insurance. You or your new employer would have to pay the full premium, including the part that was previously subsidized by your employer. But conceptually this isn’t too difficult. This already exists to a limited extent with COBRA, which allows people to continue the insurance policy they had with their previous employer, as long as they pay the full premium.

Few are talking about portability, however. Most of the current insurance “reform” debate instead focuses on the guaranteed issue and community rating provisions of the House- and Senate-passed bills. I oppose these provisions, but they have broad-based bipartisan support. Yet those Republicans who claim to support these provisions do not support the other policies required to make these provisions effective. These Republicans have taken a politically savvy but substantively inconsistent (and, I believe, irresponsible) position that could come back to bite them.

There is a broad policy consensus that guaranteed issue and community rating cannot work by themselves. The Wall Street Journal editorializes about it today, and some left-of-center bloggers have been writing about this for a few weeks.

But since you read KeithHennessey.com, you learned about it nearly six months ago. It’s a little weird to reprise a former post, but here goes.

(posted August 4, 2009 as part of A health care fallback strategy, or merely a messaging shift?)

Four sides of a box

The President, his Cabinet and staff, and Congressional Democrats are fanning out across the country to talk about proposed legislative changes to health insurance rules. The most important for this discussion are:

- Guaranteed issue and renewal: Everyone can buy health insurance, no matter what their medical condition. And everyone can renew their insurance, no matter what their medical condition.

- Community rating: Everyone pays the same premium, no matter what their medical condition.

(Caveat: The pending legislation would mandate modified community rating. Premiums could vary, but only within certain limits.)

These provisions would mean lower premiums for people who are sick (e.g. with cancer) or have a high risk of getting sick (e.g., disease free, but with a family history of cancer, or a lifetime smoker). They would mean higher premiums for those who are healthy and have a relatively lower chance of getting sick. These are redistributive policies that benefit the sick or likely-to-be-sick at the expense of the likely-to-be-healthy.

To make them work you have to make the low-risk people buy health insurance.

Here’s an extreme example. The numbers are silly, but I’m trying to illustrate the concepts.

- Imagine the world consists of two people, Bob and Charlie.

- Bob is healthy. His expected health costs next year are $5,000.

- Charlie has cancer. His expected health costs next year are $95,000.

- Under current law, Charlie probably can’t buy health insurance. If he can, he has to pay about $95,000 for it, which may be more than he can afford.

- If you implement guaranteed issue and (strict) community rating, then Charlie can buy health insurance, and Bob and Charlie each pay the same $50,000 premium.

- Under this new policy Charlie is a big winner, Bob a big loser.

- Bob may choose instead to go uninsured, rather than pay $45K more in premiums than his expected health costs. If he does, then Charlie’s back to paying $95K, since there’s no one to subsidize him.

For this system to work you have to require that Bob buy health insurance and pay the subsidy implicit in his community rated premium. You need an individual mandate to make guaranteed issue and community rating work, so you can force predictably healthy people to subsidize through higher premiums the predictably sick.

If you want the biggest health insurance reforms being pushed by the President and Speaker (guaranteed issue and renewal, and a version of community rating), then you also have to have an individual mandate.

But an individual mandate means everyone must have or buy health insurance. There will be low-income people not covered by Medicaid who won’t be able to afford health insurance. If you want them to buy, you’ll either have to subsidize them or force them to make some extremely difficult choices within their already tight budgets. Elected officials will choose the subsidy route.

You need to subsidize lots of low-income (and even low-to-moderate income) people if you implement an individual mandate.

Now the President has said that any increased spending must not increase the budget deficit. The subsidies necessitated by the mandate must therefore be offset with spending cuts or, in the Congressional Democrat view of the world, with tax increases.

You need to cut spending We have completed the four-sided box. Start by presuming that it’s too hard to enact a big bill. Assume that strategically you want to enact only the insurance reforms that you think are the most politically attractive component of the bill: You’re right back where you started. To enact the health insurance reforms, you need a complete bill that includes an individual mandate, subsidies, and politically painful offsets. You can drop the employer mandate, and you certainly don’t need an obscene $1+ trillion of subsidies. My point is simply that you can’t hive off the insurance mandates and make the policy work. House Democrats who think they can jam the Senate by sending over popular incremental bills should talk to their policy experts. It’s possible to split off the subsidies, but you can’t make guaranteed issue and community rating work by themselves. Congressional Republicans (especially in the Senate) may need to be ready to explain how they can say they support guaranteed issue and community rating if they simultaneously oppose the individual mandates, or the subsidies, or the spending cuts and tax increases needed to offset the subsidies.

It’s dead.

Comprehensive health care reform is dead again.

Yesterday I compared the comprehensive bill to Schrodinger’s cat: it was both alive and dead, and this uncertainty would be resolved only when we could see inside the box of the House Democratic Caucus.

Speaker Pelosi opened the box for us yesterday:

In its present form without any change, I don’t think it’s possible to pass the Senate bill in the House.

But the House folding and passing the Senate bill was the highest probability path to a signed comprehensive law. The path the Speaker is pursuing instead, of getting the Senate to act on a separate second bill, is too hard to execute logistically, substantively, and politically.

I am therefore updating my predictions once again, highlighting important changes over the past week in red:

| Today | Thursday 21 Jan | Tuesday 19 Jan | Sunday 17 Jan | |

| Ram it through | 1% | 1% | 10% | 25% |

| House folds | 4% | 15% | 30% | 25% |

| Reconciliation | 1% | 1% | 1% | 3% |

| Deal with Snowe | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Two bills, aka House folds “with a reconciliation sidecar” | 3% | 5% | 2% | — |

| Collapse | 90% | 77% | 45% | 45% |

I wrote yesterday that the bill is not dead until the Speaker says it’s dead. I think she in effect did so yesterday. Based on this development I have increased my prediction of collapse to 90%, and I believe the comprehensive bill is dead.

Let us examine each option in turn:

- Ram it through – Ruled out by the President on Wednesday.

- House folds – Ruled out yesterday by the Speaker, at least for the time being.

- Reconciliation – Neither the White House nor Congressional Democrats appear to have seriously considered using reconciliation as a substitute for the work already done.

- Deal with Snowe – The Washington Post reports that, when asked if the bills are dead, Senator Snowe responded, “I never say anything is dead, but clearly I think they have to revisit the entire issue.” This leans hard against tweaking the current bills to get her vote.

- Two bills, aka House passes the Senate-passed bill “with a reconciliation sidecar” – Other than Senate Budget Committee Chairman Conrad acknowledging that it’s technically possible, I know of no interest, support, or even willingness to consider this idea among Senate Democrats.

I can discern at least five viewpoints within the House Democratic caucus:

- We need a comprehensive law, but I will not vote for the Senate-passed bill without changes. Let’s pass the Senate-passed bill and fix it with a separate reconciliation bill.

- We need a comprehensive law, but the two bill strategy is too hard to execute. I hate it, but let’s just pass the Senate-passed bill. It’s better than nothing.

- I’m OK voting for the Senate-passed bill with or without a second bill.

- I do not want to vote on anything more this year for fear of losing my seat. (Privately) I wouldn’t even vote again for the House-passed bill if you brought it to the floor today.

- I would like a comprehensive law and I am not afraid of losing my seat. I can comfortably vote aye for any of the substantive plans under discussion. But health care is not my top priority, X is. If Democrats get killed in November, I’ll keep my seat, but our legislative margins will be so much slimmer I won’t be able to do good things on X. We tried, I supported it, the playing field changed. Now the long-term political and policy cost of a health care victory is too great, not to me personally, but to my ability to pursue my policy priorities. Senate Democratic Campaign Committee Chairman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) may have been making this kind of calculation when he said, “I don’t think we want to do health care for the next three months.” This is a debate about the 2010 agenda, not just whether a particular health care reform bill is good enough.

Press attention and outside liberal pressure are focused on whether those in group (1) can be moved into group (2). They appear to be ignoring those in groups (4) and (5), who I think are more important and an even harder sell. Even if House liberals all flipped to support the Senate-passed bill under pressure from the President and the Speaker, I cannot see how the Speaker convinces groups (4) and (5) to switch, with or without a second bill.

In addition it seems there is a House-Senate split among Democrats who want a comprehensive law. Some key Senate Democrats see what is to them a viable and reasonable path: the House should just pass the Senate-passed bill. This strategy conveniently means no Democratic Senator would need to vote again, post-Brown. The Speaker is pursuing a two bill strategy instead, while Team Obama is reportedly shopping the idea of bipartisan incremental bills. The Speaker, White House, and key Senate Democrats appear to be pulling in three different directions.