Challenges of the two bill strategy

Speaker Pelosi, Leader Reid, and their Administration allies face seven challenges in implementing the two bill strategy:

- Yes/no political question

- Yes/no reconciliation question

- Sequencing

- Money

- Procedural

- Substance & vote counting, especially in the House

- Timing

I have a companion post which describes the mechanics of the two bill strategy. Warning: the mechanics post is intended as a technical reference and gets into more detail than you may want.

Last August I posted a primer on reconciliation which may be helpful.

1. Yes/no political question

Irrespective of the bills’ substantive details, can Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid convince each of 217 House Democrats and 50 Senate Democrats that it is in their crass political self-interest to vote aye (multiple times) and have a major health bill become law?

Most Democrats are from safe districts so this isn’t an issue. But there are some House Democrats who voted aye for House passage and are nervous about voting aye a second time.

Argument: You already voted aye. Your opponent this November can already run an ad against you for that vote. There is therefore no political cost to you voting aye a second time.

Response: If you vote aye a second time, the bills will become law. You are then committed to defending these laws and your votes for them through the remainder of this year (and thereafter). If you change your vote to no, the bill will not become law and you give yourself a response to that negative ad. Your message changes to “I changed my mind, and here’s why I opposed the bills.”

The crass and self-interested political question is not “Do I do additional damage by voting aye a second time?” It is “Given that my opponent will attack me for voting aye last October, am I better off (A) voting aye, having it become law, and defending it, or (B) voting no, having it not become law, and explaining why I changed my vote?”

Let’s use an extreme example to illustrate this tradeoff. Suppose you cared only about getting re-elected. Suppose you knew today that on Election Day a new comprehensive health care law would be intensely unpopular with 95% of your constituents. Clearly you would be politically better off to change your vote and explain why you did. You would still take heat for voting aye last October, but that’s true in either case. And some fraction of those 95% of your constituents would give you credit for voting no the second time and helping kill the bill. Even if all of the other 5% took retribution against you for flip-flopping, the severe imbalance in the numbers makes it politically advantageous to change your vote.

This is an extreme example, and I am not arguing it makes sense for all these nervous House Democrats to switch. I am instead making the less contentious claims that (i) there is a potential political benefit to switching from an aye to a no, and (ii) this political benefit gets bigger the less popular is a new health care law in fall of 2010.

A new law may make the anger and opposition go away. If so, the arguments for sticking with your aye vote are valid. But if you think opposition will continue to climb and intensify after a new bill is signed into law, then it may be in your narrow political interest to switch from aye to no.

Nervous House Democrats from purple districts know this, presenting a significant challenge for Speaker Pelosi.

2. Yes/no reconciliation question

Do Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid lose any votes if they use reconciliation to pass Bill #2?

I think this is the smallest challenge of all those I list. I think the proposed process is an abuse of the intent and spirit of reconciliation. Even when made aggressively by Congressional Republicans, that argument so far does not appear to be dissuading Congressional Democrats from pursuing this path.

Still, if only two or three House Democrats who previously voted aye decide they cannot take the political heat associated with what is being labeled as a “nuclear option,” they could jeopardize the entire strategy. The vote-counting margins are so thin, especially in the House, that this procedural debate could still matter.

It also feels like this issue is still ripening. It appears the Blair House Debate and the President’s upcoming remarks this week are in part designed to provide those nervous Congressional Democrats with air cover for the process aspects of some tough votes.

It doesn’t really matter what the viewers of Fox News or MSNBC, or the editors of the New York Times or Wall Street Journal think on this point, except to the extent they influence the behavior of those swing votes in the House.

3. Sequencing

The core challenge here is to sequence three votes:

- House passage of the Senate-passed bill (which I call Bill #1);

- House passage of the new reconciliation bill (Bill #2);

- Senate passage of Bill #2.

(I’m glossing over working out differences between the House-passed and Senate-passed versions of Bill #2. For this purpose that’s a detail.)

Each leader wants (needs?) the other body to go first:

- Some Democratic Senators will want to vote for a new reconciliation bill only if they are certain that it will lead to a new law. They therefore want the House to pass Bill #2 before the Senate does, so that if Speaker Pelosi can’t get the votes for Bill #2, the Senate Democrats don’t have to vote and don’t have to take any risk.

- Some Democratic House members feel the same way about the Senate, and won’t want to vote aye for Bill #2 in case the Senate might not pass it. I would imagine more nervous House Democrats from purple districts might fit into this group. Many of these Members already feel burned from when they cast a politically damaging vote for a cap-and-trade bill that died in the Senate.

- I expect some House Democrats will insist the Senate pass the reconciliation bill (#2) before the House passes Bill #1. They fear that, if the House passes Bill #1 unchanged and the President signs it into law, the Senate has little incentive to take any additional political risk and Bill #2 will die in the Senate. Interestingly, I can imagine both some House liberals and some more moderate House Democrats (especially the pro-life ones) falling into this group.

These dynamics definitely exist at the Member level. They may also exist at the Leader level. I wrote about the possible blame-shifting exit strategy dynamics among Team Obama, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid last week.

Lesson #1 in how a bill really becomes a law: The House and Senate are two separate legislative bodies that occasionally work out their differences.

Corollary: Never underestimate the potential for friction and distrust between the House and Senate, even (especially?) between Members of the same party. Former Republican House Majority Leader Dick Armey once said, “The Democrats are the opponents. The Senate is the enemy.” This sentiment exists in both parties and both bodies.

Illustrating this, here is a POLITICO article from Friday:

Still, Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid have been in a staring contest of sorts about who should move first on a revised health care bill. To that end, the speaker and her no. 2 prodded the Senate Friday to move forward with reconciliation.

That’s in part a sign of the distrust that has crept in between Democrats in the two chambers, with some House Democrats angry that the more moderate Senate caucus hasn’t been able to pass a liberal version of reform.

… “Yesterday took us further down the path,” Pelosi said of Thursdays summit. “Now, we’ll put something together. Harry – will see what he can get the votes for, and then we’ll go from there.”

Update: After further discussions it looks like the Speaker and Leader Reid may not have much flexibility to choose a sequence. The money problem I describe below in #4 appears unsolvable. If so, that means Bill #1 will have to pass the House (but not necessarily be signed into law) before the Senate can consider Bill #2. In addition, while there is technically a choice in which body goes first on Bill #2, I would bet heavily on the House going first. If the Senate goes first then two Senate committees need to mark up Bill #2 (Finance & HELP). That’s a nightmare.

So I predict that the likely sequence is:

- House passes Bill #1, the Senate-passed bill.

- The House initiates and passes Bill #2, the reconciliation bill.

- The Senate passes Bill #2, the reconciliation bill.

- The President signs Bill #1.

- The President signs Bill #2.

4. Money (& sequencing again)

The Congress is still operating under the quantitative limits established by last year’s budget resolution. This will continue to be true even though Congress is now working on this year’s budget resolution. The old limits apply until a conference report on the new budget resolution is passed by the House and Senate. That would rarely happen before the mid-April statutory deadline for the budget resolution, and it’s a safe bet that Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid will delay it as needed to avoid further complicating their health care efforts.

Still, Bill #2 must comply with the limits in last year’s budget resolution. Since the House Rules Committee can waive budget rules with a simple majority, this is probably a bigger practical challenge in the Senate, where waiving those same rules requires 60 votes (and therefore the cooperation of a Senate Republican).

There is also a vote counting dynamic that goes beyond the formal procedural limits. The President and Democratic Leaders worked hard to get CBO to say their bills reduce the budget deficit over ten years, and also over the long run. I think those claims are misleading because of factors ignored in the CBO analysis, but my view is beside the point.

The tension here is that the leaders will want to spend taxpayer money in Bill #2 to include popular provisions that engender political support from wavering Democrats. (A cynic would call this “buying votes with taxpayer money.”) Since Bill #2 is a reconciliation bill, it must reduce the budget deficit over ten years and must not increase it in the long run (I’m oversimplifying).

There is an additional and potentially fatal challenge introduced by the two bill strategy. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus said it well but I’ll bracketed language to further clarify it:

<

blockquote>The general rule is, if there is reconciliation, you have to amend something that is passed

Let’s look at an example from my way-too-detailed post Mechanics of the two bill strategy.

Example

- The Cornhusker Kickback is a provision in Bill #1 that increases federal spending on Medicaid for Nebraska. If this bill and provision were signed into law, and then Bill #2 contained a provision to repeal it, Bill #2 would reduce federal spending. CBO would score this as savings, which could then be spent within Bill #2 on sweeter benefits for someone without Bill #2 resulting in a net deficit increase.

- But if Bill #1 is not yet law, then repealing a non-existent provision of law doesn’t save any money, and they won’t get scored with any savings. This means they cannot offset their other spending, and their Bill #2 will increase the deficit.

This is a huge problem. if the strategy is to hold Bill #1 until Bill #2 has passed the Senate. There may be a procedural way to work around this problem, but I don’t know it. If there is not a way around it, they may be forced to enact Bill #1 into law before the Senate passes Bill #2.

You can see how the money, procedure, and sequencing all interact to cause a potential nightmare for the Speaker and Leader Reid:

- While there is tension about which House should pass the reconciliation bill (#2) first, it seems like an easy strategic call to save the House vote on Bill #1 until last.

- If they cannot find a way around this scoring problem, then when the Senate considers Bill #2 it cannot get any scoring credit for deficit-reducing amendments it makes to Bill #1.

- This makes it harder to spend money in Bill #2 to build support for it in both the House and Senate.

- There may be other complications with trying to amend a law that does not yet exist. I’m still exploring this. In the extreme, it may mean that Bill #1 has to become law for Bill #2 to avoid 60-vote points of order in the Senate.

- The conventional wisdom is that there’s no way Speaker Pelosi can pass Bill #1 unless her members are certain Bill #2 will become law. So far this has meant that Bill #1 has to wait for Bill #2.

- Potential catch-22: Bill #1 must become law first for Bill #2 to survive the Senate, but House Democrats will not pass Bill #1 and send it to the President until the Senate passes Bill #2.

Press reports and my sources suggest Democrats are hard at work on this problem. I will surmise that there may be tricky procedural ways to work around it. If so, those solutions would strengthen Republican process abuse arguments, but to Democrats those have to look trivial compared to this potential problem.

I don’t understand this problem as well as I should, and procedural discussions are ongoing. I will update this section as I learn more.

Update: Further conversations convince me there is no way around this. The House will have to pass Bill #1 (the Senate-passed bill) before the Senate can consider Bill #2 (the reconciliation bill). Technically, the President doesn’t have to sign Bill #1 into law before the Senate can consider Bill #2, but that’s a minor point. I am updating my mechanics post to reflect this.

5. Procedural

I have described two procedural challenges resulting from reconciliation:

- Bill #2 must reduce the budget deficit over ten years and in the long run, as scored by CBO. (There are more particulars which I will gloss over.)

- Bill #2 can’t be scored right if it amends a non-existent law. This is an effect of an unusual two bill strategy.

The other two big procedural challenges are the Senate’s Byrd rule and the vote-a-rama.

The Senate’s Byrd rule

Oversimplifying, the Byrd rule precludes you from including provisions in Bill #2 (which is a reconciliation bill) that don’t affect spending or taxes. An exception is made for a provision that does not affect spending or taxes by itself but is a necessary term or condition of a provision that does.

You can ignore this limitation if you have 60 votes to waive the Byrd rule. Leader Reid will not have 60 votes to waive anything.

I have not discussed the details with experts, but I imagine this is a big challenge for the Stupak abortion provision. That debate centers around limitations the federal government would place on health insurance plans sold through new State-based exchanges, including plans that are not directly subsidized with federal dollars.

The first order test for the Byrd rule has two parts and is simple:

- If we remove this provision from the bill, does the bill’s score change? Does federal spending or revenues change?

- If we remove this provision from the bill, is there another provision that affects spending or revenues that will no longer work?

I don’t know what the discussions are with the Senate parliamentarian, but based on my experience it would seem the Stupak amendment would fail both tests. As with all Byrd rule tests, this procedural judgment is independent of anyone’s policy views. Whether the provision is good or bad policy is irrelevant to the procedural test. It does not matter whether the state exchanges would work well or as Mr. Stupak would like. They would still function without his amendment, and so it’s difficult to argue that his language is a necessary term or condition of the exchanges.

This makes me think that one of the primary challenges for Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid looks like this:

- Speaker Pelosi needs Mr. Stupak and his allies to vote for Bill #2 in the House.

- To get these votes, she needs to include his amendment (or maybe some variant thereof depending on their negotiations).

- Setting aside the separable problem of whether including his language causes other House members to vote no, let’s assume the Stupak language violates the Byrd rule.

- Even if the House includes his language and passes the bill, that language is subject to a 60-vote test in the Senate.

- I assume that 41 Republicans would vote against waiving the Byrd rule on the Stupak language. They would do this even though almost all of them are pro-life.

- The Stupak amendment would automatically be removed from the bill. Ironically this probably makes it easier for Leader Reid to get 50 more liberal Democrats to vote for final passage.

- But Bill #2 has now been changed and must again be passed by the House. How does the Speaker now get Mr. Stupak and his allies to support the bill without his language?

If my view on how the Byrd rule applies to the Stupak language is correct, then this is the most important but not the only Byrd rule consequence of a possible Bill #2. The President’s proposed new federal authority to regulate health insurance premiums might also violate the Byrd rule. I’m sure there are others.

In each case, the practical problem is more than just the loss of the policy. It’s the votes the leaders lose from Members who demand that policy change for their aye votes.

As a cultural observation, few things exacerbate institutional House-Senate tension like the Byrd rule. House leaders, Members, and staff often (justifiably) lose their cool when this Senate rule places practical limits on their ability to pass legislation in the House.

A wild card challenge to Democratic Leaders would be if Senator Byrd were healthy enough to weigh in publicly on whether reconciliation should be used for this whole strategy. A single Democratic Senator could not block the strategy’s implementation any more than could a single Republican, but the psychological effect on the Senate majority of hypothetical Byrd opposition would be devastating. Such opposition would be consistent with Senator Byrd’s longstanding views on the appropriate use of reconciliation.

For more background on reconciliation, see my post from last August: What is reconciliation?

The Senate’s vote-a-rama

I have few legacies in Washington, but one is that I coined the term vote-a-rama as a young Senate Budget Committee staffer in 1995.

Senate floor debate on a reconciliation bill is limited to 20 hours. There is no limit on amendments that can be offered. This means that, after two full days of debate and amendments, twenty hours will have expired. Any amendments which are queued up (or are then offered) are then voted on, in sequence, with no debate (in theory). In practice the Senators will often agree to precede each vote with 30 seconds of debate from the proponent and 30 seconds from an opponent.

For a normal reconciliation bill, there are anywhere from 15 to 60 amendments stacked up. Assume 15 minutes per vote when the Senate is working at top speed. The Senate spends many hours in a seemingly endless series of stacked votes. This is called the vote-a-rama.

The Senate floor is usually mostly empty. When things are really busy there might be eight or ten Senators and twice that many staff on the floor.

During the vote-a-rama you have 100 Senators and about the same number of staff on the Senate floor or in the cloakrooms for anywhere from four to fifteen or more consecutive hours.

A well-disciplined Senate majority party can defeat every amendment with a simple majority by simply voting to table (kill) each amendment. This has a slightly different procedural and political feel than defeating the amendment but the same practical effect. Still, the minority can often use the vote-a-rama to force members of the majority party to take politically tough votes. I would expect vulnerable Senate Democrats to be looking to vote with Republicans on some of these votes to avoid political risks for their campaign. This should not be too big of a challenge for Leader Reid, since he needs to hold only 50 of 59 for each tabling vote. He can allow vulnerable individual Democrats to take a walk on particularly difficult amendments.

The novel twist this time would be the possibility of a Senate Republican filibuster by amendment during the vote-a-rama. Even a single Republican could, in theory, offer an infinite sequence of amendments to each word of the bill, never allowing Leader Reid to get to final passage.

This has never happened. Even in times of extreme partisan stress over highly contentious reconciliation bills, the minority has forced a handful or two of tough votes and then allowed the reconciliation bill to move to final passage. But in sixteen years I have never seen the reconciliation process placed under as much stress as is suggested by this strategy.

This provokes two questions to which I do not know the answer:

- If Senate Republicans continue to press their argument that use of reconciliation is abusive in this case, will they avail themselves of this tool?

- Does Leader Reid have a procedural option to shut it down? I will guess his staff are exploring options for a ruling by the chair to shut down such a sequence if the Chair (controlled by Reid) determines the extended sequence of amendments is dilatory.

This is another area where I know only the questions.

6. Substance & vote counting

Suppose there are 217 House Democrats and 50 Senate Democrats who are willing to vote for health care reform as a political matter and to use reconciliation as a procedural matter. You still need them all to agree to the same substance and legislative text.

The primary challenge to Democratic success on the two bill strategy is getting 217 House votes for both bills. Leader Reid’s job of holding 50 votes for one bill is very difficult, but not as difficult as Speaker Pelosi’s job of rounding up 217 votes for two bills. Reid needs 50 of the 59 who voted for the Senate-passed bill. Pelosi needs 217 votes. 220 voted aye in October, but two of them are no longer in the House and Republican Rep. Cao now says he’s a no. She is playing with zero margin, or maybe less than that.

House Republican Whip Eric Cantor released a memo that describes Speaker Pelosi’s challenge in getting to 217. The key difficulty to predicting what will happen is that we don’t know how close Cantor’s memo is to the Speaker’s reality. If you pay attention to only one thing in the near future, watch what these various swing vote House Democrats say about whether they will support or oppose a reconciliation bill.

This is interesting because it’s the reverse of last fall’s legislative process. When they were operating under regular order and Leader Reid needed 60 of 60 Senate Democrats to shut down a filibuster, he had the more challenging job. (Pelosi’s job was not simple then by any measure.) This relative difficulty last fall gave the Senate [Democrats] leverage over the House [Democrats] on substance and process. This is a fundamental rule of House-Senate negotiations: if one body has only one option that can pass, that body wins in negotiations with the other. Vote counting weakness becomes negotiating leverage.

Now the vote counting weakness and therefore the negotiating leverage is reversed. In House-Senate negotiations Speaker Pelosi and the House have the upper hand over Leader Reid and the Senate for all issues on which she can legitimately claim that the issue matters for getting a particular Member’s vote. If losing a substantive issue means Leader Reid loses one of his 59 votes on Bill #2, he still has eight more to go before he jeopardizes final passage.

This is why everyone is so focused on Mr. Stupak and his allies. It also means each House Democrat suddenly has tremendous leverage over the House leaders and the President. I don’t know that many of them will be bold/stupid enough to use that leverage, but the next Cornhusker Kickback is far more likely to be for a Democratic House Member than a Democratic Senator.

7. Timing

Recent chatter is about an Easter recess deadline. That would leave the leaders four weeks to overcome all of these challenges.

Congressional recesses are useful forcing mechanisms but I won’t treat this as an absolute even if the President sets it this week. Health care legislative deadline credibility evaporated last year.

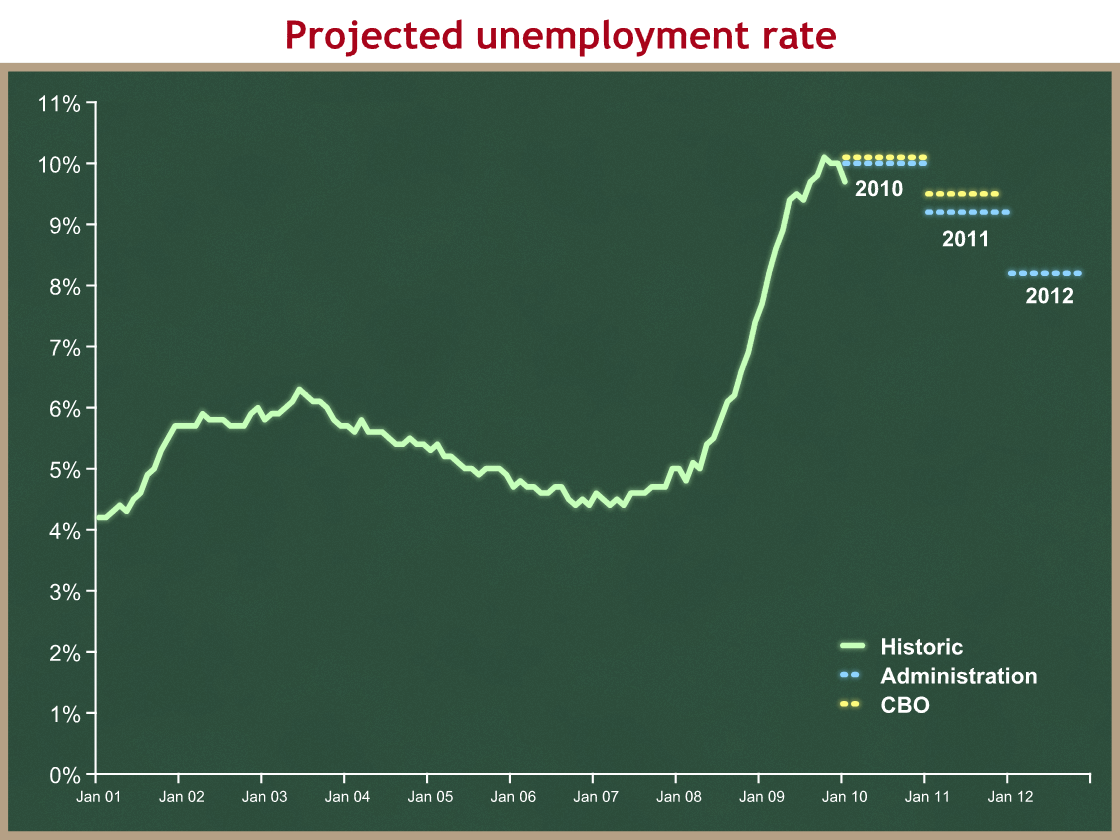

More important is how the passage of time affects general enthusiasm within the House and Senate Democratic caucus. Today it seems like they are gung ho, energized by the Blair House debate (I struggle to understand why). Will the popularity of these bills continue to slide as time passes, and, if so, how much harder will that make Speaker Pelosi’s effort to corral the votes she needs?

I have been arguing for a while that time is not the President’s friend on this legislation, and that last fall he should have pushed Congress to move much faster. While I think events have proven this argument correct, I underestimated the President’s and his allies’ willingness to press forward despite large and increasing opposition. I mistakenly thought they would have given up long ago.

(Photo credits: Hurdles by iowa_spirit_walker)

Mechanics of the two bill strategy

I am going to describe the mechanics of the anticipated “two bill strategy” to enact health care reform using reconciliation.

If you don’t care about all this procedural mumbo jumbo you can skip this post and head over to my strategic analysis: Challenges of the two bill strategy. I intend this to be a reference post for those who want the gory details.

This is a follow-up post to What is reconciliation? (posted 5 August 2009).

Last August I wrote two other posts analyzing the prospects for using reconciliation for health care reform:

- How reconciliation might be used for health reform (posted 5 August 2009)

- Doing health care through reconciliation is even harder than I thought (posted 6 August 2009).

This post in effect updates and replaces those two posts for the current legislative environment.

Thanks to two experts who helped check this. I will update it to reflect suggestions and corrections from others.

Update: I think the “Bill #2 amending a bill that is not yet current law” problem is unsolvable. This changes the likely sequence. I have updated my projected sequence to reflect this.

Step by step

For this explanation I will assume success at each stage of the process, ultimately leading to President Obama achieving victory and enacting comprehensive health reform into law. The following is what I believe would be the most “normal” scenario for a highly unusual procedural path. It’s unusual not just because of the use of reconciliation, but because Congressional Democrats would be attempting to enact one substantive set of reforms spread across two bills, one of which realistically cannot change. This is procedurally novel for policy changes of this magnitude. It is also incredibly difficult to execute. You will seen so that there are many potential failure points.

There are many even more complex variants of this basic scenario. I will ignore them — this is complex enough. If you understand all of what’s below then you can understand variants of it.

I will assume that the House will go first on Bill #2 (the reconciliation bill), and that Bill #2 will pass both Houses in identical form before Bill #1 passes the House. This is a reasonable scenario but by no means the only one. I am choosing this because it is the closest approximation to “standard practice,” given an extremely unusual two bill process. Indeed, a budget problem discussed below may require the leaders to enact Bill #1 into law before Bill #2 comes to the Senate floor. For more on this challenge, please see challenge #4 in Challenges of the two bill strategy. Luckily for me, the bulk of the explanation below remains intact even if you assume a different sequence.

The hard steps are in red. The really hard steps are in bold red.

- House and Senate Democrats negotiate a substantive agreement on health care reform that they think can get 217 votes in the House and 50 in the Senate.

- Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid are the ultimate arbiters and sign off on the final deal.

- The White House may be able to help, but they don’t formally have the pen. Since we know the President will sign any bill(s) that make it to his desk, the substantive agreement of the President’s advisors is helpful but not necessary. The Administration’s role is a supporting one.

- Speaker Pelosi needs 217 rather than 218 votes because the House is down three members, so 217 is a majority. Please see House Minority Whip Eric Cantor’s memo to get a feel for the Speaker’s vote-counting challenge.

- For majority votes Leader Reid needs 50 Senators rather than 51 because VP Biden can break ties. On other questions (like waiving certain points of order) he still needs 60 and the VP plays no role.

- As a formal procedural matter this substantive agreement is not essential, but they would be crazy to proceed without doing so.

- As a part of this substantive agreement and vote-counting exercise, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid reach a procedural agreement on which bill goes first and which body goes first.

- Since I think they cannot figure out a way around the Senate scoring problem, then I think this sequence is the most likely: (updated to reflect better information on the Senate scoring problem)

- House passes Bill #1, the original Senate-passed bill.

- House passes Bill #2, the new reconciliation bill.

- Now that the House has passed Bill #1, the Senate passes Bill #2.

- House and Senate conference or ping-pong Bill #2 until they have passed identical text.

- Bill #1 is sent to the President.

- The President signs Bill #1.

- Bill #2 is sent to the President.

- The President signs Bill #2.

- (I will assume the other sequence for the rest of this explanation, not this one.)

- I will assume they figure out a way around the scoring problem described below and sequence the bills this way:

- House passes Bill #2, the new reconciliation bill.

- Senate passes Bill #2.

- House and Senate conference or ping-pong Bill #2 until they have passed identical text.

- House passes Bill #1, the original Senate-passed bill.

- Both bills are sent to the President.

- The President signs Bill #1.

- The President signs Bill #2.

- The Leaders tell committee staff to draft the agreement as two bills:

- Bill #1: The Senate-passed bill is already drafted and not a word can be changed, so there is no work to be done there.

- Bill #2: Draft a new bill, the text of which is the agreement minusBill #1 so that if both bills become law, the substantive deal is in effect.

- They probably draft Bill #2 as if Bill #1 has already been signed into law. Example: Bill #2 would say “Repeal the provision of law that is the Cornhusker Kickback.” Thus the President would sign Bill #1 into law creating the Cornhusker kickback, and then immediately sign Bill #2 into law repealing that provision of law. In my primary scenario, the Cornhusker kickback would be the law of the land for only a few seconds. In my fallback scenario Bill #1 is law for many days while Bill #2 moves through the process. This is one reason why the fallback scenario is so difficult.

- They need to draft Bill #2 so it can move through the legislative process as a reconciliation bill.

- Some in Washington are referring to bill #2 as the “reconciliation sidecar.”

- They get CBO scoring. They then tweak the bill to make it (a) comply with reconciliation rules and (b) satisfy whatever political constraints are mandated by the votes you need to get. Assuming no change from before, this means CBO must say the bill reduces the deficit over 10 years, and that it reduces the deficit in the long run. In some cases they then have to check to make sure the CBO-induced changes have not changed their vote count. This iterative process could easily take at least a week during which all sorts of other things can go wrong.

- One area of procedural uncertainty and therefore risk is that you would draft (reconciliation) Bill #2 to amend Bill #1. How does CBO score Bill #2, given that Bill #1 is not yet law? This could cause budget points of order (and therefore 60-vote problems) in the Senate.

- Example: The Cornhusker Kickback is a provision in Bill #1 that increases Federal spending on Medicaid for Nebraska. If this provision were signed into law, and then Bill #2 contained a provision to repeal it, Bill #2 would reduce federal spending. CBO would score this as savings which could then be spent within Bill #2 on sweeter benefits for someone without resulting in a net deficit increase.

- But if Bill #1 is not yet law, then repealing a non-existent provision of law doesn’t save any money, and they will not get scored with any savings. This means they cannot offset your other spending, and their Bill #2 will increase the deficit.

- This is a major problem if the strategy is to hold Bill #2 until Bill #1 has passed the Senate. If there is a way to work around this problem, I don’t know it. If there is not a way around it, they may be forced to enact Bill #1 into law before the Senate passes Bill #2. But this causes severe tension between House and Senate Democrats because House Democrats will fear the Senate will abandon Bill #2 after Bill #1 becomes law.

- Update: I am strengthening my view that there is no way around this. This makes my alternate sequence more likely than my main sequence. I have updated this post to reflect this scoring challenge, and therefore to assume that the House must pass Bill #1 before the Senate can consider Bill #2. The Speaker might try to play a game by holding a House-passed Bill #1 and not sending it to the President until Bill #2 has passed both the House and Senate, but I don’t think that’s her problem. Her problem is getting House Democrats who don’t trust the Senate Democrats to vote for Bill #1 before Bill #2 looks certain.

- One area of procedural uncertainty and therefore risk is that you would draft (reconciliation) Bill #2 to amend Bill #1. How does CBO score Bill #2, given that Bill #1 is not yet law? This could cause budget points of order (and therefore 60-vote problems) in the Senate.

- The House passes Bill #1, the Senate-passed bill, with at least 217 Democratic votes.

- The Speaker might try to instruct the House Clerk to hold Bill #1 and not send it to the President until Bill #2 has passed both bodies. I don’t know for how long she can do this.

- The Speaker might try to instruct the House Clerk to hold Bill #1 and not send it to the President until Bill #2 has passed both bodies. I don’t know for how long she can do this.

- The House then initiates and passes Bill #2, the reconciliation bill. Assuming they solve this Senate-side scoring problem, we begin with the House passing bill #2, the reconciliation bill, with at least 217 votes.

- The House Budget Committee formally creates an empty shell of a Bill #2 and reports it out of committee on a party line vote. There’s no real substantive markup and no amendments. The Budget Committee is just doing the formal procedural work for the bill given to the Chairman by the Speaker.

- The Speaker gives the legislative language for the new Bill #2 to the Chair of the House Rules Committee (Rep. Louise Slaughter).

- None of the three committees of jurisdiction need to meet or mark up the bill: Ways & Means, Energy & Commerce, or Education & Labor.

- The House Rules Committee reports a rule that will “self-execute” to insert the new legislative language of the agreement into the text of Bill #2 as reported from the House Budget Committee.

- The House passes this rule for bill #2.

- The House passes bill #2.

- Bill #2 goes to the Senate.

- The Senate proceeds to, debates, amends, and passes bill #2 using the reconciliation process.

- When Bill #2 arrives in the Senate, Leader Reid holds it at the desk so it is not referred to a Senate committee.

- Reid proceeds to bill #2. This is a privileged motion, so if Republicans challenge it Reid can immediately have and win a majority vote to begin debate on the reconciliation bill.

- (If necessary) Reid makes a procedural motion to “refer the bill to the Finance Committee and report forthwith” to satisfy reconciliation rules.

- Neither the HELP Committee nor the Finance Committee needs to meet or mark up the bill.

- The Senate spends twenty hours debating bill #2 and maybe voting on amendments to it. Assume 10 hours of debate per day, so this takes two full days.

- Amendments must be germane. This is a technical term that basically means “related to something in the bill.” In a non-reconciliation bill, you can amend a bill on the Senate floor with a completely unrelated amendment.

- Amendments cannot be filibustered.

- During the amendment process, some elements of the bill may be stricken by the Byrd rule. I describe the Byrd rule below.

- The Senate has a long sequence of votes in the vote-a-rama. Some are majority votes (need 51 or 50+VP to win), other point of order waiver votes require 60 to win. This is the one area where Republicans may have procedural leverage. (See #5 in Challenges of the two bill strategy for details.)

- The Senate votes on final passage. A majority vote (51 Senators or 50+VP) wins.

- No extended debate (aka “filibuster”) is possible at any stage in this process, but Republicans can technically offer an infinite sequence of amendments in the vote-a-rama. (See #5 here.)

- If the Senate does not amend the House-passed version of Bill #2, then it is enrolled by the House Clerk and then is ready to go to the President. But it doesn’t yet.

- If the Senate does amend the House-passed version of Bill #2, then the differences between the House-passed and Senate-passed versions of Bill #2 need to be worked out. Either the two bodies go to conference, or they ping pong Bill #2.

- Conference path:

- The Senate-passed version of Bill #2 goes to the House.

- The House then disagrees with the Senate amendment, requests a conference with the Senate, and appoints conferees. These messages travel to the Senate.

- The Senate insists on its amendment, agrees to the conference with the House, and appoints conferees. (That’s three formal procedural steps that each take only a few seconds.) Unlike with a non-reconciliation bill, if Republicans try to block any of these steps Leader Reid can accomplish each instantly with only a simple majority. Senate Republicans could force him through three votes, but they lack the procedural ability to block going to conference.

- Now the House and Senate are in conference.

- Democratic conferees from the House and Senate work out a compromise between the House-passed and Senate-passed versions of Bill #2.They ignore/shut out Republican conferees.

- As necessary, Pelosi and Reid jointly arbitrate (or negotiate between them) any issues the conferees can’t resolve. Or Pelosi and Reid bypass the conferees and work out all the substantive differences themselves. This would be unusual but fits with the current environment.

- All the while both Democratic leaders and their whips are checking with their members to ensure that the final conference report can get 217 House votes and 50 Senate votes.

- Senate Budget Committee staff, supervised by Reid and Pelosi’s staff, do a Byrd bathon the agreed conference text.

- They review the bill text and identify Byrd rule violations.

- They check any questionable provisions with the Senate parliamentarians. This is a staff process over several days.

- They tell the Leaders about the violations.

- The Leaders then remove those provisions from the conference report, even if they think in theory that those provisions might be supported by 60 or more Senators. They do this because they cannot risk Senate Republicans voting strategically not to waive the Byrd rule, and because if a single provision of a conference report is stricken by the Byrd rule, the entire conference report dies and you have to start from scratch. The leaders have to be extremely risk averse in this situation.

- Democratic leaders and whips recheck to make sure they have 217 + 50.

- A majority of the House conferees (the Democrats) and a majority of the Senate conferees (the Democrats) sign the conference report on Bill #2.

- One body (I’ll guess the Senate goes first, since the House vote is probably harder to win) passes the conference report, again under reconciliation protections.

- Reid’s motion to proceed to the conference report is privileged, so it cannot be filibustered. If Senate Rs force a vote on it, Reid needs only a majority to win.

- Ten hours of debate are allowed on the conference report, followed by a majority vote on final passage. No amendment is in order, and no extended debate/filibuster is possible.

- Points of order can be raised, but if the Democratic staff did their job with the scoring and Byrd bath, no points of order are available against the conference report.

- 41 Senate Rs therefore have no procedural tools to prevent a majority from passing the conference report on Bill #2.

- The conference report on Bill #2 goes to the House.

- With 217 or more votes, the House passes the conference report on Bill #2. The bill is enrolled by the House Clerk and then is ready to go to the President. But it doesn’t yet. The Speaker instructs the House Clerk to hold it.

- Ping pong path:

- The Senate-amended version of Bill #2 returns to the House.

- The House takes it up and either passes it or amends it and send it back to the Senate.

- The Senate either debates and passes it as is, or amends it and sends it back to the House.

- Repeat as necessary until both bodies have passed the same text. If it returns to the Senate, the same reconciliation rules and protections apply (20h of debate, no filibustering, amendments and vote-a-rama).

- At the end of the ping pong, Bill #2 is enrolled by the House Clerk and then is ready to go to the President. But it doesn’t yet.

- Conference path:

- Now that Bill #2 is ready to go to the President, the House passes Bill #1.

- The Speaker tells the House clerk to enroll Bill #1 (the original Senate-passed bill) and send it to the President, immediately followed by Bill #2 (the reconciliation bill).

- At a triumphal signing ceremony, the President signs Bill #1, immediately followed by Bill #2.

- The substantive agreement for comprehensive reform is now law.

See, that wasn’t so hard. Or was it?

If you’d like you can read about the challenges of the two bill strategy.

What can President Obama learn from President Bush’s bipartisan successes?

Conventional wisdom says the tenure of President George W. Bush was dominated by partisanship. There were deep partisan splits over the war in Iraq, enhanced interrogation, wiretapping, the 2003 tax cuts, and Social Security reform.

This conventional wisdom ignores significant bipartisan legislative accomplishments led by President Bush. I will focus on domestic policy accomplishments.

Each of the following major laws was enacted on a bipartisan vote:

- The 2001 tax cuts;

- the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001-2;

- the 2002 extension of Trade Promotion Authority;

- the 2003 medicare law;

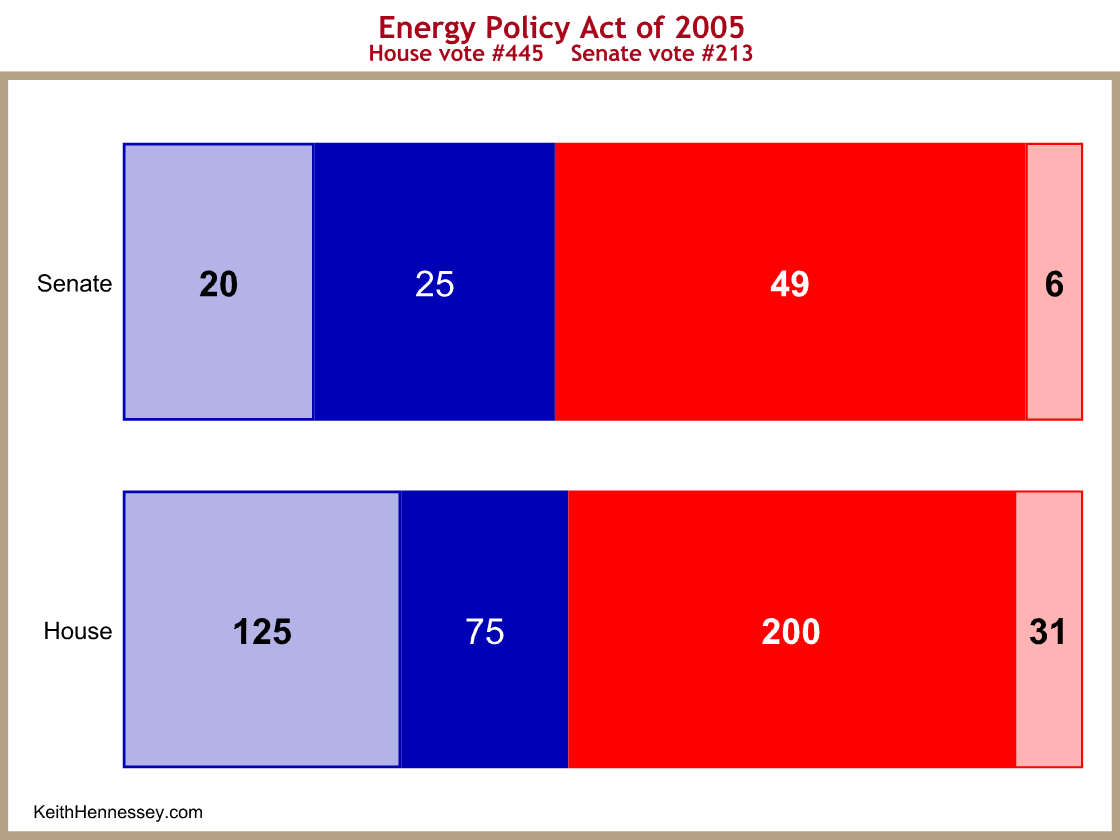

- the 2005 energy law focused on electricity;

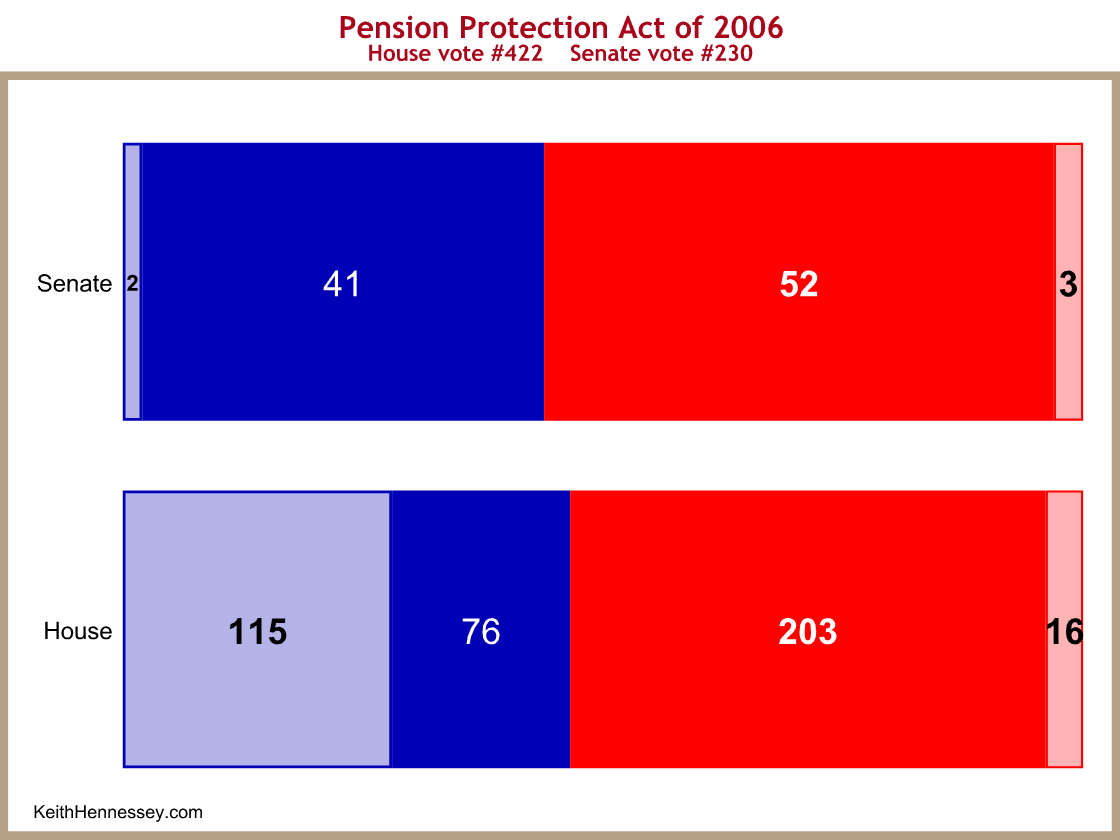

- the 2006 pension reform law;

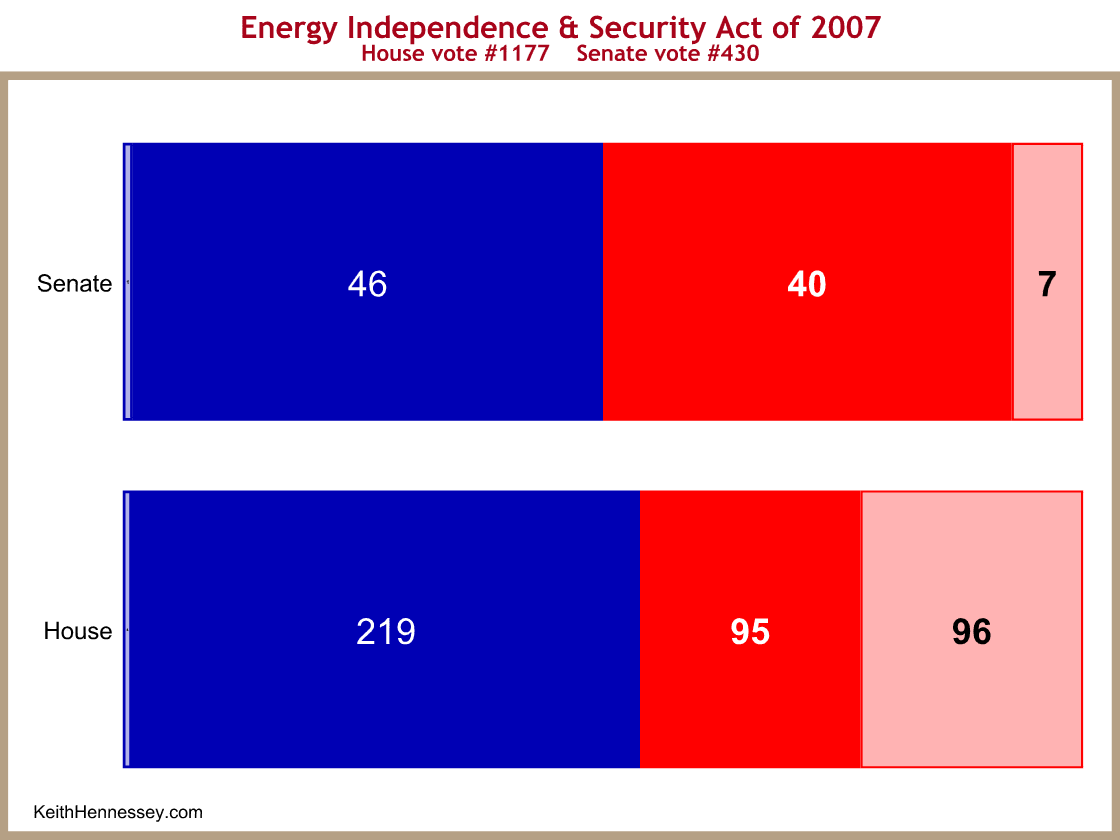

- the 2007 energy law focused on fuel;

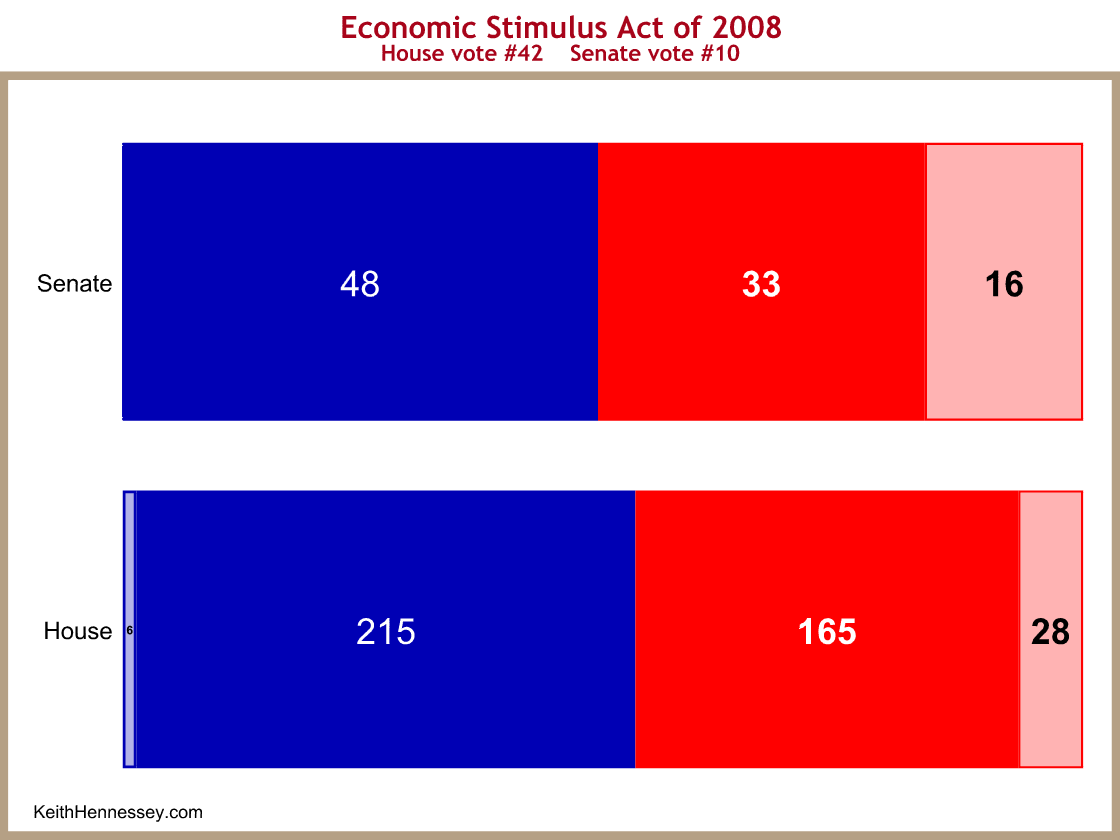

- the 2008 stimulus law;

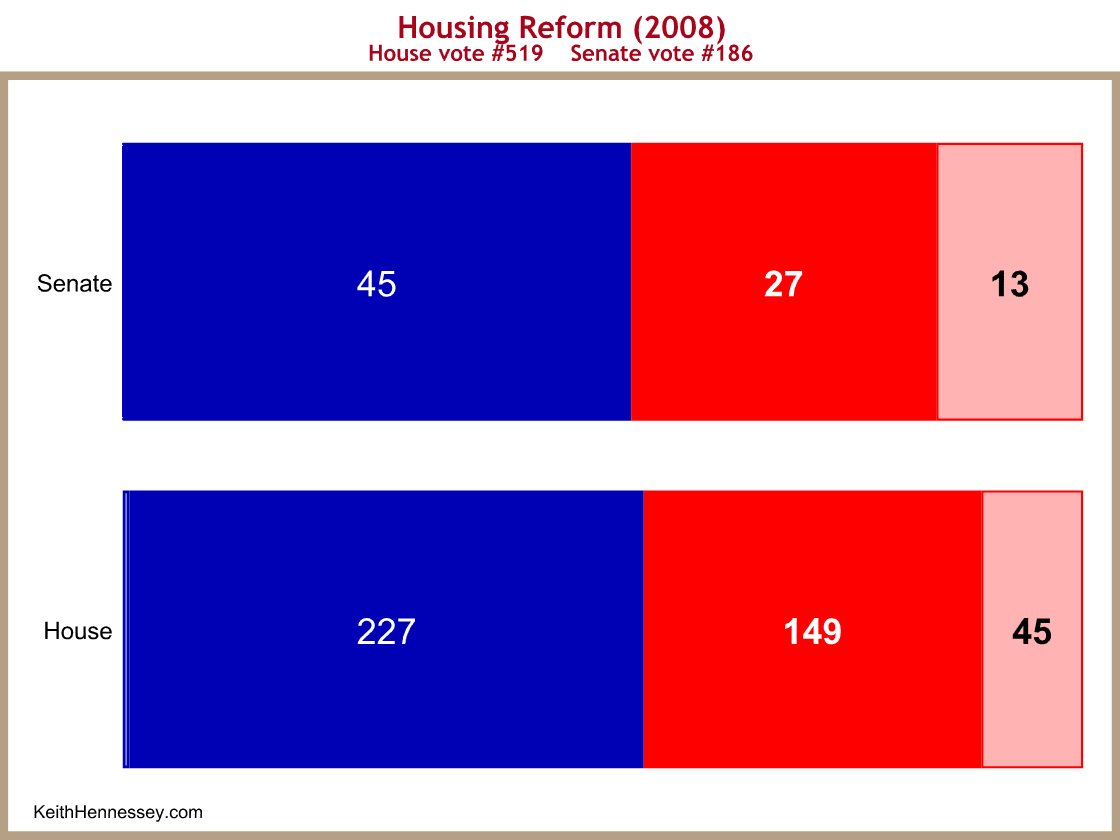

- the 2008 housing reform law; and

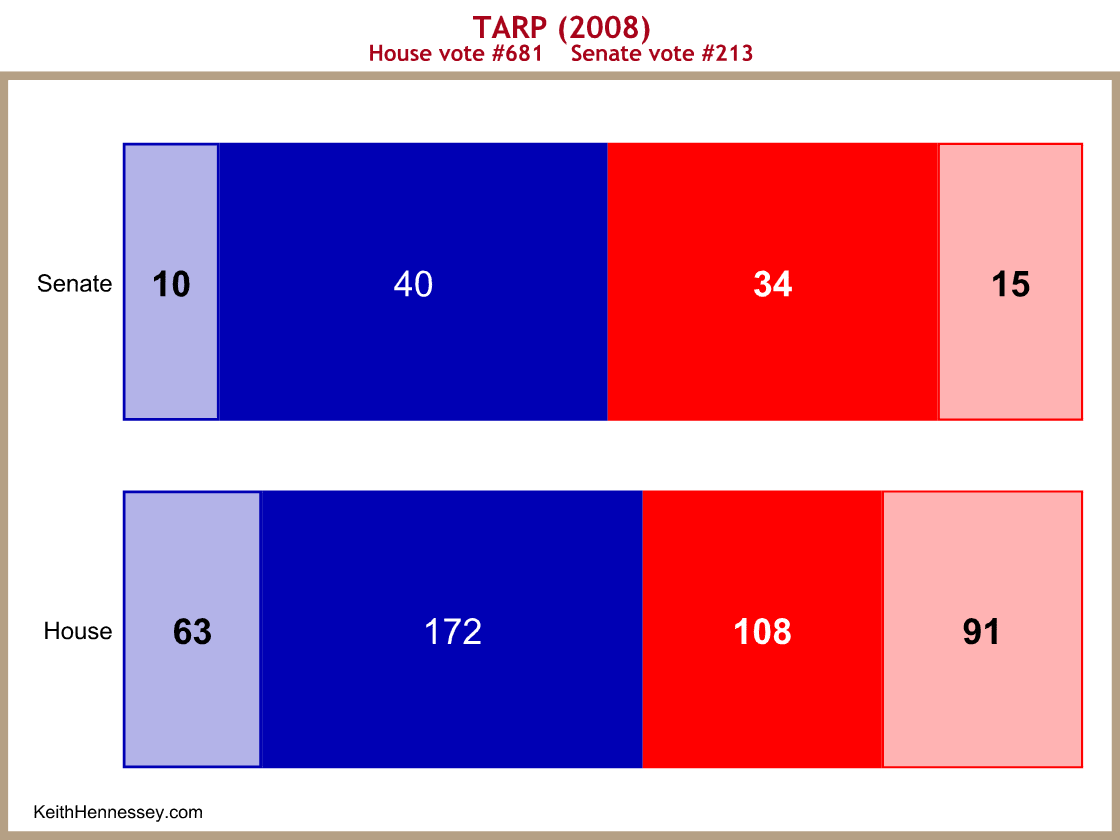

- the 2008 TARP law.

President Bush also reached across party lines to reform immigration law. His bipartisan outreach on this issue was successful, but the legislation failed due to opposition from both wings. In that effort President Bush’s team negotiated with a broad group in the Senate, led by Senator Kennedy on the left and Senator Kyl on the right. President Bush’s attempts deeply split his own party, yet he persisted until it became apparent there was not a 60 vote coalition to succeed.

I imagine some readers are skeptical of the above list so, once again, I’m going to show you some pictures. I’m going to show you a lot of pictures. I want to hammer home the Bush-bipartisan success point. I will then try to draw some lessons for Team Obama.

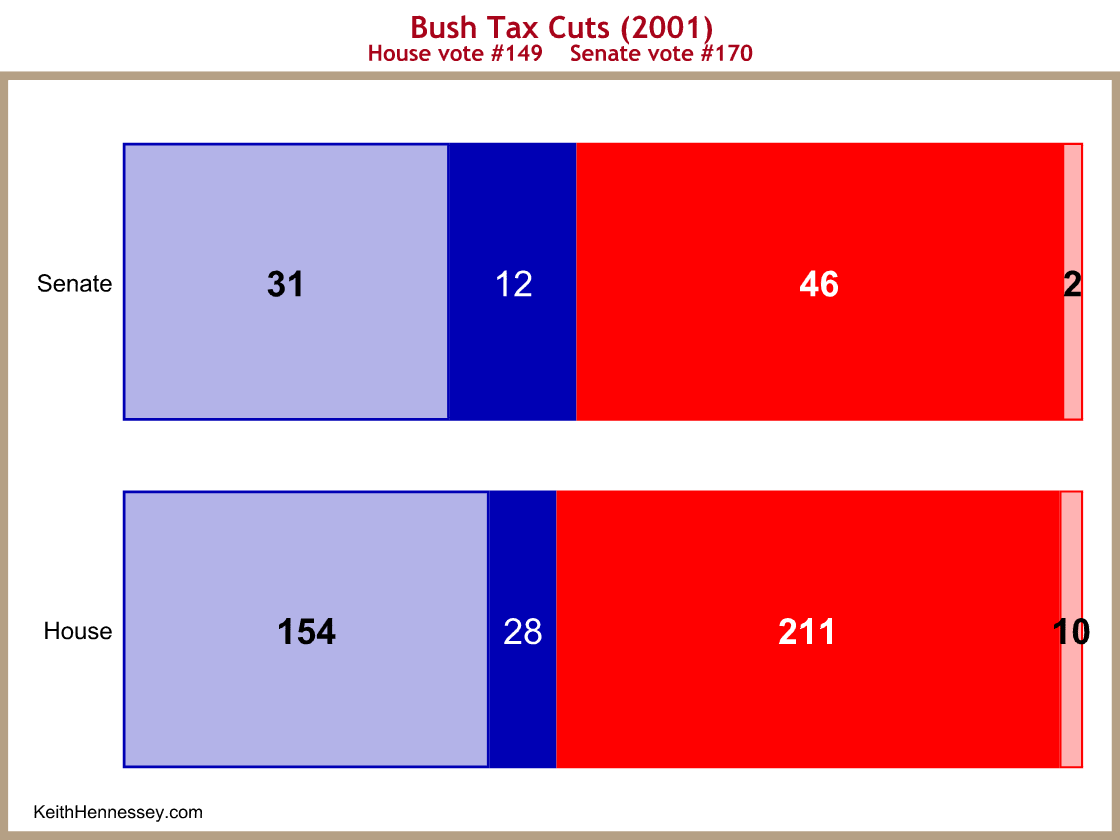

Let’s begin with the 2001 tax cuts to orient ourselves to the graph format.

- Dark shading means they voted aye. Light shading means they voted no. So in the top bar in this first graph, 12 Democrats and 46 Republicans voted aye, while 31 Democrats and 2 Republicans voted no.

- Blue shows Democrats and independents caucusing with Democrats (like Senators Lieberman and Sanders).

- Red shows Republicans.

- I left out those who didn’t vote, which explains why many Senate votes don’t total 100, and many House votes don’t total 435.

- In each case I tallied the vote on final passage.

- As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

On final passage of the Bush tax cuts of 2001:

- in the Senate 46 Republicans and 12 Democrats voted aye, while 2 Republicans and 31 Democrats voted no; and

- in the House 211 Republicans and 28 Democrats voted aye, while 10 Republicans and 154 Democrats voted no.

It should be fairly easy to see that the 2001 tax cuts were enacted by a center-right coalition. Almost all Republicans supported the final product, and about 1 in 4 (Senate) or 1 in 6 (House) Democrats voted aye.

This bill was bipartisan largely because the Bush White House, Senate Majority Leader Lott and Senator Grassley worked closely with Democratic Senators Breaux and Baucus to craft a bill and keep moderate Democratic Senators onboard. We used the reconciliation process, and therefore had 58 votes when we needed only 51 for final passage in the Senate.

You can see that the 2001 tax cuts would not have had even a simple majority in the Senate if Republicans had acted alone. The Senate was split 50-50 at the time.

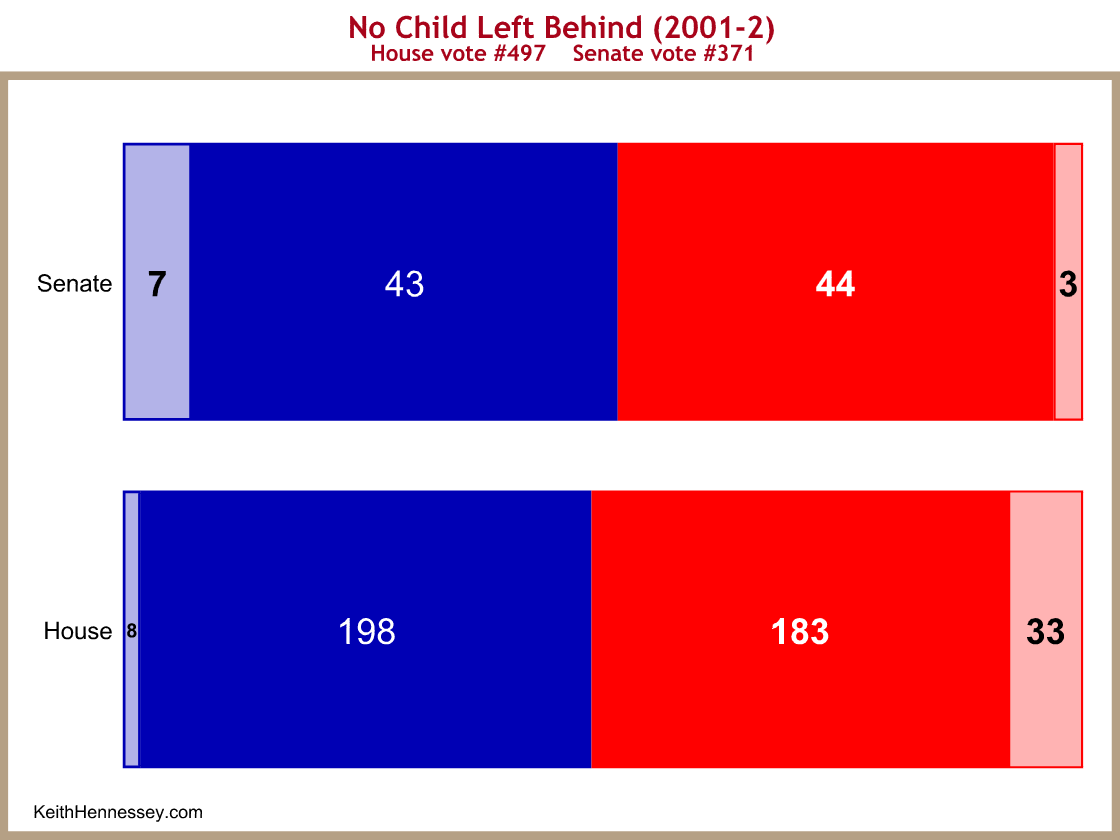

Now let’s turn to education.

This was a broad bipartisan coalition. President Bush reached out to Senator Kennedy and instructed his team to negotiate directly with Kennedy. You can see the result. This is about as bipartisan as it gets for major legislation.

The Senate was a 51-49 Democratic majority when this bill became law.

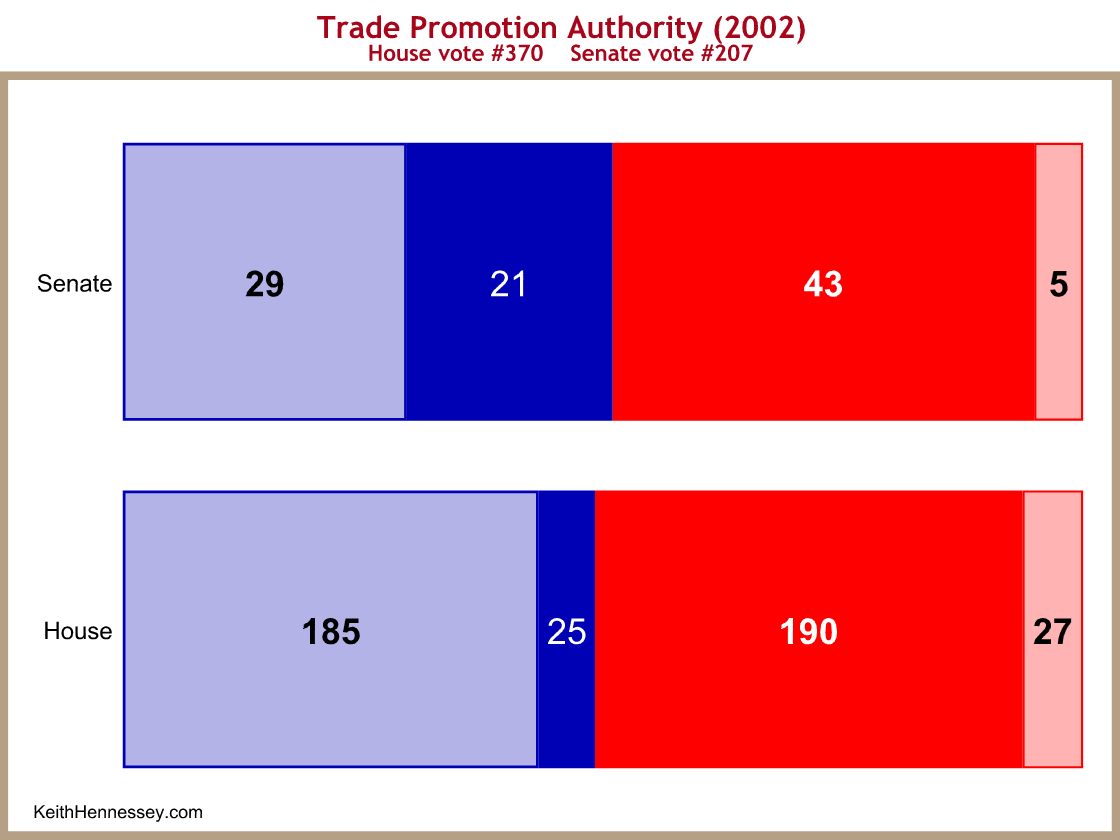

Next up, trade.

Trade Promotion Authority, formerly known as fast track, gives the President authority to negotiate trade deals with other countries and have them subject to only an up-or-down vote by Congress, rather than being amended to death. It is essential for Congress to give the President this authority if you’re to have free trade agreements.

Again you can see the center-right coalition that dominates much of American economic policymaking. This has even a little more Democratic support than the 2001 tax cuts, and slightly more opposition from protectionist Republicans. As with the 2001 tax cut, you can see that there are more economic centrist Democrats in the Senate than in the House.

This bill could not have passed either the House or the Senate with only Republican votes. A bipartisan coalition was necessary for legislative success.

This is with a 51-49 Democratic majority in the Senate.

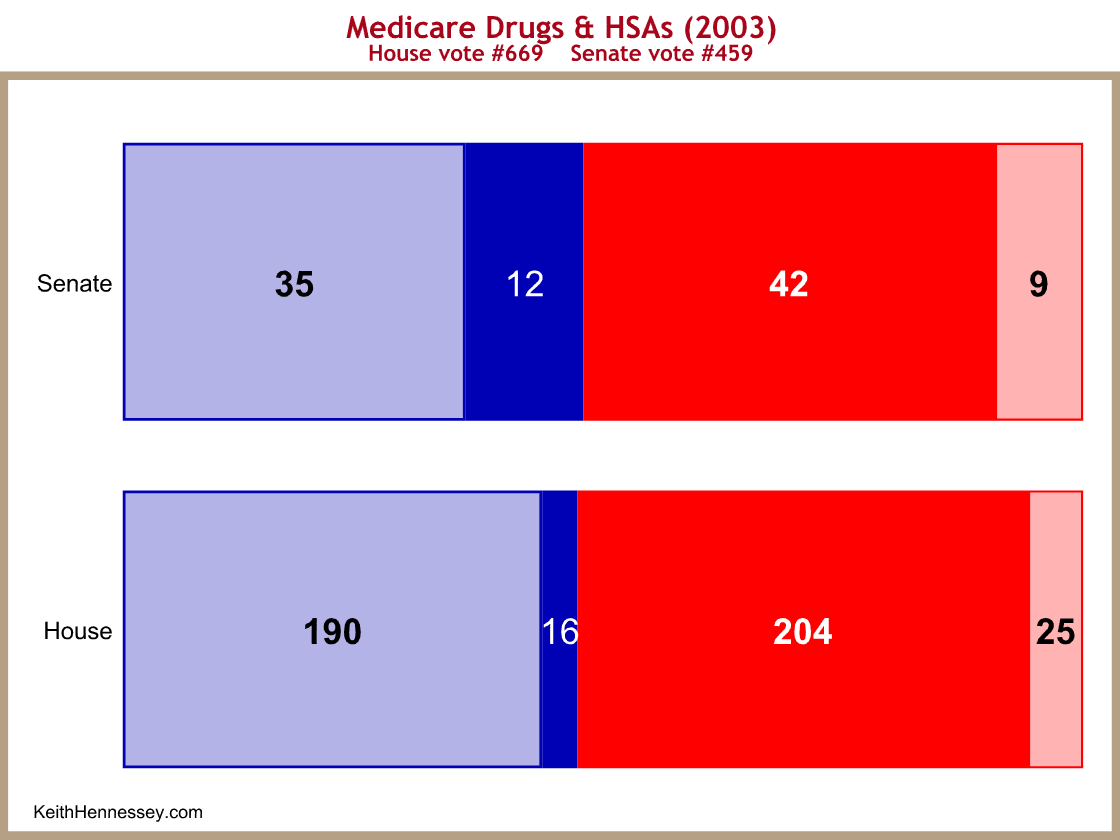

Medicare and Health Savings Accounts are next.

Now we’re back to a Republican majority in the Senate.

Once again, President Bush, his team, and Senator Grassley worked closely with centrist Democratic Senators Baucus and Breaux to negotiate a deal. The final details were hammered out in a fierce negotiation between Baucus/Breaux and Rep. Bill Thomas (R-CA), with extensive White House support.

President Bush held a few meetings at the White House with Baucus, Breaux, and the key Republicans to strengthen the coalition and keep the ball moving forward. This bill created the Medicare drug benefit (which split Republicans) and Health Savings Accounts (which Republicans and conservatives especially like). Democratic leaders opposed this bill, but we managed to hold Democratic moderates anyway.

Once again, the winning majority coalition in both the House and Senate was bipartisan, and the bill could not have become law without Democratic support. A key vote before Senate final passage was a cloture vote, in which some of the 9 Republicans who ultimately voted no supported cloture.

Now we turn to the first major energy law during the Bush tenure.

Senators Bingaman and Baucus were key to this legislative success, which you can see was more bipartisan than some of the prior successes. The legislative process was filled with amendments and negotiations across the partisan aisle and fierce regional conflicts.

Senate Democrats split roughly equally and 75 House Democrats supported final passage. This law focused on electricity (rather than fuel), which sometimes has more of a regional policy focus than a partisan split. This bill originated with VP Cheney’s Energy Task Force, which was labeled by the Left as a dark and evil conspiracy. And yet the final legislation had significant bipartisan support.

Pension reform gets less attention than the others but is important.

I highlight this law because it is easy for pension issues to break down along party lines, with Republicans favoring management interests, Democrats favoring labor interests, and the taxpayer getting shafted. Republican committee chairmen and the Bush Administration reached across party lines to elevate the interests of protecting the pension system, future retirees, and taxpayers, battling against tremendous lobbying pressure from business and labor interest groups to relax the pension rules and allow pension plans to be underfunded.

The law was far from a complete victory for good pension policy, but it was a definite improvement over what preceded. And again, you can see the tremendous breadth of bipartisan support.

Still in President Bush’s tenure, we now shift to Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. The 2007 energy law focused on fuel.

In the 2007 State of the Union Address, President Bush proposed to increase fuel economy standards (CAFE), and to increase the mandated amount of renewable fuels (ethanol) that had to be blended with gasoline. This “energy security” proposal infuriated conservatives – the Wall Street Journal editorial page trashed us for it all year. The President recognized that, with new Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, he would have to build a different legislative coalition than had worked for him when his own party was in the majority.

The final bill was negotiated via an exchange of letters between the Bush White House and Speaker Pelosi. You can see unanimous Democratic support and Republicans deeply split, especially in the House. As with his unsuccessful immigration reform efforts, President Bush was willing to negotiate a compromise with leaders and even wingers from the other party.

Next is the early 2008 stimulus law.

Before announcing his stimulus proposal, President Bush called Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Reid to brief them on it. They urged him to propose a broad outline rather than detailed specifics. President Bush agreed to do so.

President Bush hosted a meeting with the bipartisan / bicameral leaders to discuss the stimulus, similar in composition to the upcoming Blair House meeting. That Cabinet Room meeting was unproductive.

The President then assigned his Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, to negotiate directly with Speaker Pelosi and Minority Leader Boehner. The three of them negotiated a compromise that followed the President’s outline, and that the President, Speaker, and Minority Leader supported. Almost all Democrats supported the bill, as did most Republicans, but with a significant contingent voting no.

Housing reform legislation was stuck for a long time until Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac started to collapse. Then it suddenly broke free.

Again you can see the results of negotiations between a Republican President and a Democratic-majority House and Senate. The bill had unanimous Democratic support and a fairly serious split on the Republican side.

Finally we have the TARP.

The first version of TARP was negotiated by Secretary Paulson with Democratic and Republican leaders and committee chairmen in an intense and conflict-ridden negotiation. The legislation failed spectacularly on the floor of the House the first time. The President’s team then negotiated by phone with House and Senate leaders of both parties, leading to a few modifications to the original package. The Senate formed a broad center-out coalition to pass the bill easily, which then succeeded the second time around in the House.

You can see broad bipartisan support, as well as significant opposition from both parties. As with the 2007 energy law and the 2008 stimulus, the 2008 TARP was enacted with Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, with leaders from the opposite party working out compromises with a Republican President.

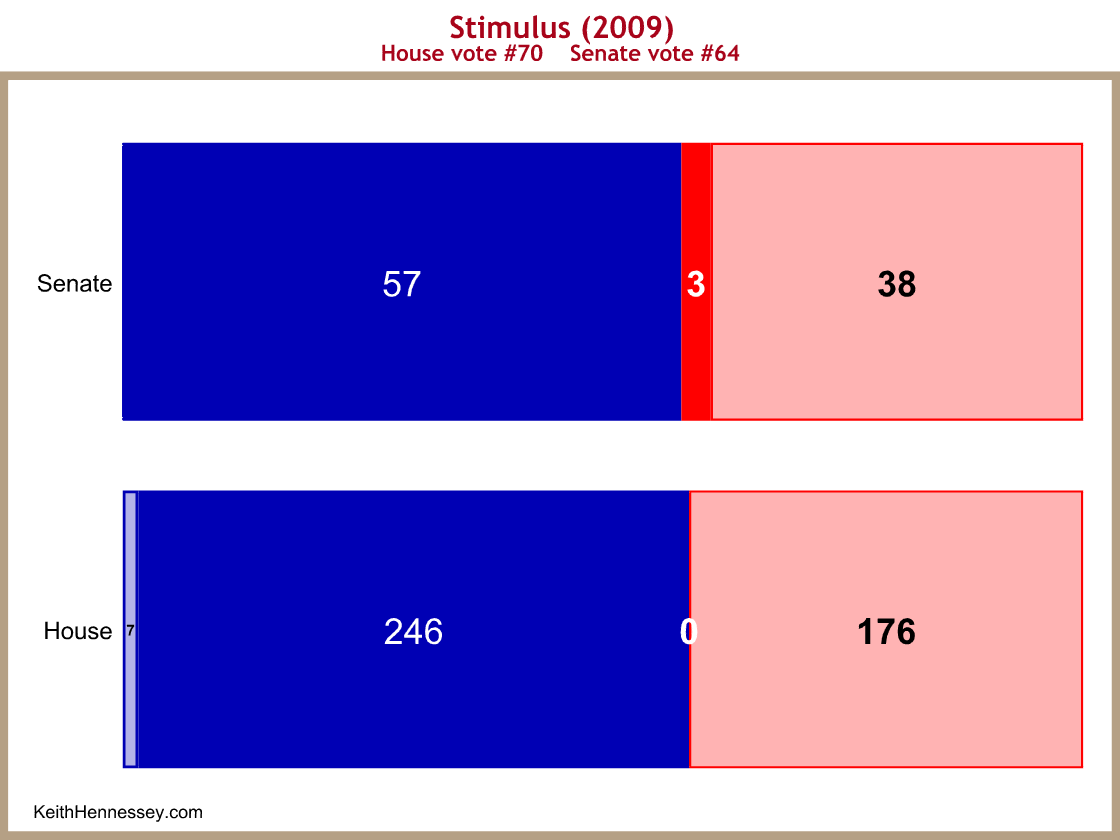

Now we turn to the three big domestic policy issues of President Obama’s tenure so far. We begin with the February 2009 stimulus.

Other than three Senate Republicans, the bill was passed and became law on party line votes. There were no negotiations with Congressional Republicans.

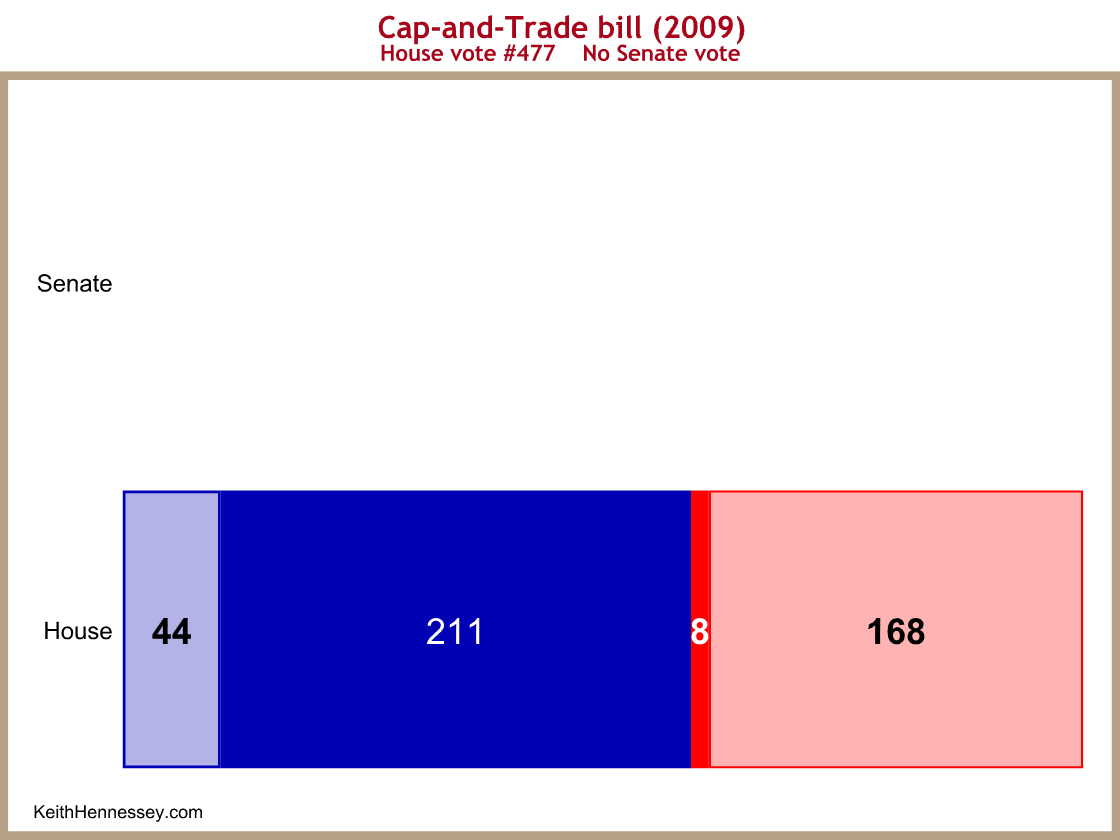

Cap-and-trade is next, but only in the House.

Eight House Republicans voted for the bill, providing Speaker Pelosi with her winning margin. A significant block of Democrats voted no.

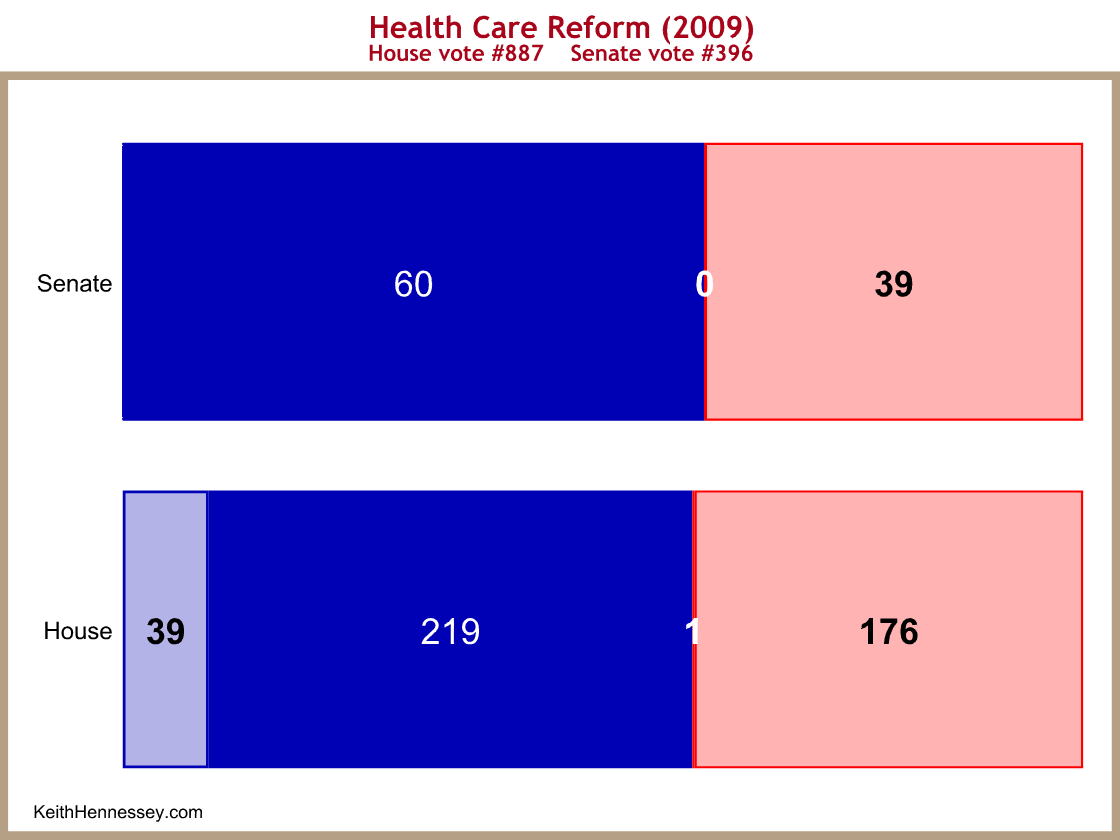

We end with the health care bills that are the subject of this Thursday’s meeting.

Once again you can see straight partisanship.

Observations and common threads

Senate Republicans peaked at 56 votes during Bush’s tenure.

President Bush used reconciliation twice three times: once in 2001 for the bipartisan tax cuts, once in 2003 for the partisan tax cuts (not shown), and once in 2005 to cut spending.

In all other cases he had to deal with potential filibusters, occasionally from both sides of the aisle.

In Republican majority Congresses, the winning margin was often provided by Democrats, especially in the Senate.

There are at least four different versions of a bipartisan vote:

- Unifying your own party (or nearly so) and picking off a moderate block from the minority: tax cuts, TPA, Medicare/HSAs. You do this by trying to split the other side’s moderates from their party leaders.

- Picking up the majority of the other party, at the cost of a losing a significant block from your own side: 2005 energy, TARP. You do this by negotiating with the other party’s leaders.

- Working with the majority of the other party and getting all of their side while your own side splits deeply: 2007 energy, 2008 stimulus, housing. You do this by negotiating with the other party’s leaders when they’re in the majority.

- Near consensus: No Child Left Behind, Pension Protection Act (in the Senate). You do this by negotiating with everyone. Miracles occasionally happen.

Why did Bush succeed at enacting bipartisan legislation?

I assume that some on the Left will say the Republican minority is now far more unified, partisan, and obstinate than the Democratic minority ever was. I think this is silly. Whatever you think of Republicans, they’re not that unified. I’m reminded of the organized crime boss in the movie Sneakers: “Don’t kid yourself. It’s not that organized.”

I believe there are six keys to President Bush’s bipartisan legislative successes:

- He sometimes reached out to Congressional Democrats and negotiated directly with them, even at the expense of upsetting his Congressional Republican allies.

- He knew how to count votes, and when not to rely on a razor-thin partisan margin for victory.

- He knew how to nurture existing bipartisan discussions and alliances in Congress and turn them to his own advantage.

- He was willing to preemptively split his own party when necessary to get a deal.

- He knew when and how to split the other party, negotiating with Democrats who were potential supporters of a compromise and isolating those who would oppose a deal no matter what.

- He and his allies generally stuck with a traditional legislative process, which builds credibility and makes members feel they are getting their fair shot, even if they lose a vote.

President Obama needs to learn each of these lessons if he wants to succeed as President Bush did.

- President Obama explains that his proposals include {modified versions of) Republican ideas. That’s not how you bring the other party on board. You can end up at the same place by bringing members of the other party into the room and negotiating with them. Then they (in this case, Republicans) have ownership of the compromises and are more likely to support the final product. The way you get someone to agree is by bringing him into the room and negotiating with him (or her). Make the other guy feel like he got a win.

- For a year he tried to enact legislation by relying on a universe of 60 votes from which he needed 60. That’s nearly impossible to do on any important issue, especially when you simultaneously provoke the other 40 to stand firm by shutting them out.

- On health care he undercut Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus, whose bipartisan “Gang of Six” had the best chance to negotiate the core of a bipartisan compromise. Recently Leader Reid blew up a Baucus-Grassley deal on the jobs bill, further poisoning the water for any potential future bipartisan efforts. No Senate Republican can now have confidence that any Democratic committee chairman has the authority to negotiate a binding deal. Why should Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham enter into bipartisan cap-and-trade negotiations after he saw what Reid did to Baucus-Grassley?

- President Bush alienated a significant share of his own party when he announced his 2007 energy proposal, his 2008 stimulus proposal, immigration reform, and the TARP. On cap-and-trade and especially health care, President Obama has instead tried to hold onto his left wing as long as he possibly could, making the inevitable break even more painful and losing the ability to demonstrate to Republicans that he is willing to make hard choices in his own party to bring Republicans onboard.

- Bipartisan doesn’t always mean negotiating with the leaders of the party. You have to know when to negotiate with the opposition leaders, when to negotiate with a winger from the other party (e.g., Bush-Kennedy on education, or Bush-Kennedy-Kyl on immigration), and when to try to pick off a few moderates from the other party to squeak out your margin of victory. Other than Speaker Pelosi picking off eight House Republicans for cap-and-trade, Team Obama and Congressional Democrats have failed with each of these tactics. But have they actually tried?

- The traditional legislative process creates legitimacy within the halls of Congress. Committee markups, bipartisan negotiations, open amendment processes, and traditional open conferences are processes that create predictability, order, and a sense of fair play. It is much easier to cultivate members of the minority party when they perceive you are playing by the rules. Team Obama and their allies repeatedly try to bypass the rules, creating new substantive products behind closed doors and relying upon nontraditional legislative processes. This undermines both public confidence and the minority’s willingness to play ball. If Senator Reid were to allow floor amendments to be offered to major legislation, even amendments he might lose, he might not face quite so many filibusters and failed cloture votes.

If President Obama wants bipartisan legislative success, he could learn a few things from his predecessor.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Eric Draper)

The President’s new health care proposal

While I oppose the President’s health care proposals (old and new), I have to give the White House staff credit for a slick new website in advance of Thursday’s Blair House health care debate.

I will highlight a few policy elements of the President’s new proposal, then turn to tactical analysis.

Major changes in the President’s proposal

- Like the Senate bill, the President’s proposal would raise taxes on wages by 0.9 percentage points for individuals with incomes > $200K and families with incomes > $250K. In addition, the President’s new proposal would impose a 2.9 percent tax “on income from interest, dividends, annuities, royalties, and rents” for those with income above $200K (individuals) and $250K (families). Flowthrough income from ownership in a small business or partnership would not be subject to this tax.

- The President’s proposal delays the taxes on pharmaceutical and health insurance companies. It appears (but we can’t be certain) that they intend to raise the same amount of revenue from these industries, meaning that the per-year tax would go up.

- The “Cadillac tax” has been delayed to begin in 2018 and the threshholds would be $27K for families (as opposed to $23K in the Senate bill). The Senate-passed levels were so high as to be absurd – they would apply to almost no one. This exacerbates that problem. No word on whether union plans are still exempt.

- The President would create a new federal Health Insurance Rate Authority “to provide needed oversight at the Federal level and help States determine how rate review will be enforced and monitor insurance market behavior.” Health plans would therefore be subject to state and federal rate regulation. I presume this is a reaction to the recent California/Anthem premium hike story.

Strategy and tactics

Far more interesting than the substance of the new proposal (which is excruciatingly detailed) is trying to understand what Team Obama is trying to do with it.

Speaker Pelosi released a statement that she “look

POLITICO reports that White House communications director Dan Pfeiffer said:

We view this as the opening bid for the health meeting. … We took our best shot at bridging the differences. We think this makes some strong steps to improving the final product. Our hope is Republicans will come together around their plan and post it online.

Q: Whose opening bid? The President’s? Or Democrats’?

I struggle to understand how the President’s new proposal is relevant to any serious attempts at legislating if he cannot deliver either House or Senate Democrats in support of it. Maybe this is the first part of a well-coordinated strategy in which Pelosi and Reid press their own members to line up behind the President’s proposal. Or they could just be winging it again.

One week ago I wrote about four possibilities for what the President might be trying to accomplish with the Blair House meeting:

- If he thinks a Democrat-only deal is possible, then they’ll need to use reconciliation to pass a bill. The meeting is to set up that hardball legislative process by demonstrating that Republicans are uncooperative.

- If he thinks no Democrat-only bill is possible, then he may be looking to set up Republicans as the fall guy for his exit strategy.

- He may want to begin negotiations with Congressional Republicans.

- He doesn’t have a game plan.

Speaker Pelosi’s comment suggests that (1) does not yet apply. If you’re about to coordinate with House and Senate Democrats and ram through a compromise using reconciliation, you need to have a unified proposal. The point of the Blair House meeting would be to highlight obstructionist Republican behavior and justify hardball procedural tactics. If Democrats aren’t unified behind the President’s substance, then Republican opposition is once again irrelevant.

House and Senate Democratic leaders have been signaling to their friends to get ready for a big partisan reconciliation push. Doing so requires substantive agreement, at least between Pelosi and Reid. That substantive agreement clearly does not yet exist.

Somebody in the Administration put a lot of work into this proposal. It is extremely detailed, and it reads like a best effort to find a fair middle ground between two warring legislative bodies. All that substantive work is subsumed by the apparent lack of strategic coordination and substantive agreement with Members of his own party. The President’s staff appear to be trying to set up the Blair House meeting as a partisan debate, but Democrats are not yet unified. Maybe the pressure of the Blair House meeting will bring Democrats together on substance?

I will believe that a reconciliation push is going to happen only when (a) Pelosi and Reid both definitively say that it will, (b) they announce agreement on a substantive proposal, and (c) a House floor vote has been scheduled. Until then it’s just bluster. For now I continue to believe there’s a 90% chance of no law.

This strengthens my argument from last week that this Thursday Congressional Republicans should show up, propose ideas of their own, and respectfully critique the various plans. Republicans should come with their own reform ideas but should not feel obliged to unite behind a single Republican proposal. They should also ask Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid if each supports the President’s proposal as a legislative compromise. If Team Obama wants to highlight the partisan differences and Republican obstruction, then the Republicans should want to highlight their positive reform ideas, their problems with the Democratic proposals, and ongoing Democratic disunity.

Blame-shifting exit strategies?

It is possible that we are witnessing uncoordinated Democratic leaders each pursuing their own exit strategy in anticipation of legislative failure:

- The President proposes a “compromise” and blames Republicans for being unreasonable and unconstructive. Legislative failure is the Republicans’ fault, not the President’s.

- Speaker Pelosi continues to press for a two bill strategy in which the House and Senate will pass a new reconciliation bill. If the Senate cannot or will not do so, legislative failure is the Senate’s fault, not the House’s or Speaker Pelosi’s.

- Supported by outside liberals, Leader Reid points out that the House could just take up and pass the Senate-passed bill. Legislative failure is therefore not his fault or the Senate’s.

Each of these strategies is consistent with telling your allies that you’re continuing to push forward, right up until the moment you give up and blame someone else. Of these hypothetical blame-shifting rationalizations, the President’s would be the weakest. It is common knowledge that Republicans have no procedural authority to block either Speaker Pelosi’s two bill strategy, nor to prevent the House from taking up and passing the Senate-passed bill.

Maybe they’re almost ready for a big partisan legislative push using reconciliation, leading to a triumphant partisan signing ceremony at the White House. Maybe the “Never give up, never surrender!” comments from the President and Speaker Pelosi over the past month are preparation for a stunning legislative victory.

I’m still in the maybe not camp.

Six good Obama economic policies

I have been fairly aggressive in my recent criticism of the Administration. I figure it’s time I say something positive about good things they are trying to do.

Here are six of President Obama’s economic policies that I support. Several come with caveats.

- Make [some of] the Bush tax cuts permanent: The President proposes to make permanent the individual income tax rate cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 for the 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, and part of the 33% brackets. This is good.

- Caveat: He proposes to allow the other part of the 33% bracket to increase to 36%, and for the 35% bracket to increase to 39.6%. I oppose this.

- Index the Alternative Minimum Tax: The AMT is screwed up. For the past ten years Congress has annually “patched” the Alternative Minimum Tax so that it doesn’t affect millions of new taxpayers. The President proposes to permanently indexing the current AMT parameters for inflation. This is good.

- Slow out-of-control health care cost growth: The President argues that cost growth is the core problem to be solved by health care reform. Out-of-control health care cost growth (1) leaves those with health insurance with less money available for other things; (2) prevents millions of people from being able to afford health insurance; and (3) contributes to the unsustainable growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending. The Beltway health care reform debate usually focuses on only the uninsured, ignoring the other symptoms and, more importantly, the underlying cause. Kudos to the President.

- Caveat: Despite his Administration’s claims, the President did not propose policies that would have significantly slowed this cost growth. He identified a problem and then did not propose an effective solution.

- Caveat: Congress ignored the President’s problem definition and again just tried to expand taxpayer-financed coverage for the uninsured.

- Caveat: The pending legislation would dramatically increase long-term health care spending through the expansion of third-party payment for health insurance.

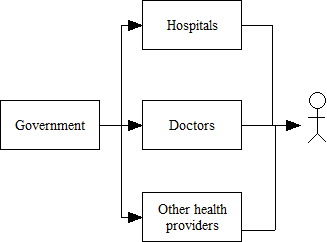

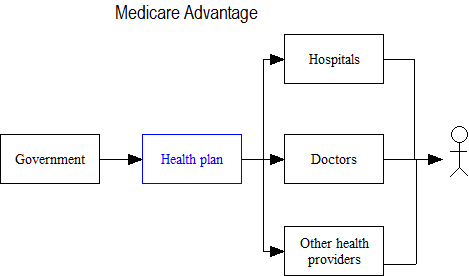

- Slow the growth of Medicare spending: The President has proposed modest policy changes to slow the growth of Medicare spending. Medicare spending is unsustainable and its growth must be slowed to prevent fiscal collapse.

- Caveat: We need to slow Medicare spending growth even more than the President has proposed.

- Caveat: He proposed to spend those savings on a new health care entitlement, undoing all the fiscal policy good of slowing spending health care growth. <forehead slap>

- Caveat: I would slow the growth of different parts of Medicare. The President is primarily squeezing Medicare Advantage plans. I would make beneficiaries pay higher cost-sharing and have more means-testing, and I would squeeze fee-for-service Medicare providers (hospitals, physicians and nurses, nursing homes, home health providers, medical equipment providers, the whole ball of wax).

- Approve Free Trade Agreements with South Korea, Panama, and Colombia: In this year’s State of the Union the President said “We will strengthen our trade relations – with key partners like South Korea and Panama and Colombia.” These are the three nations with whom the U.S. has Free Trade Agreements pending Congressional approval. I assume with this language the President means he will submit to Congress these three FTAs and push Congress to enact them this year. This is good and long overdue.

- Caveat: If he means something else by “strengthen our trade relations” then he’s playing a game.

- Caveat: I’d like to say the same thing about the global free trade negotiations based in Doha, but his language was so vague I cannot draw a positive conclusion.

- Caveat: He did almost nothing to advance free trade and free capital flows in his first year.

- Expand nuclear power: The President now supports the expansion of nuclear power: “And we’re going to have to build a new generation of safe, clean nuclear power plants in America.” His recent budget proposed significantly expanding financial support for the construction of new nuclear power plants.

- Caveat: He opposes using Yucca Mountain in Nevada as a repository for nuclear waste but offers no alternative solution.

- Caveat: Some suggest his support is contingent on enactment of a cap-and-trade bill. I see no evidence of this.

The packaging caveats in (1) and (4) are important. If Congress packages policy changes to slow Medicare spending growth with policies to increase health spending, then the result is worse than doing nothing. Similarly, if the legislative result of making some of the Bush tax cuts permanent is to cause other tax rates to go up, that’s bad.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Pete Souza)

The Blair House debate

The President has invited Congressional leaders to the Blair House ten days from now to discuss health care reform. While the press has labeled it a summit, it has much more the feel of a televised debate, a kabuki dance played out for the cameras.

I am having difficulty understanding what the President is trying to accomplish with this meeting. Four possibilities are:

- If he thinks a Democrat-only deal is possible, then they’ll need to use the reconciliation process to try to pass a bill without Republican help. If the President can portray Congressional Republicans as uncooperative, he may be able to mitigate anticipated Republican process complaints from implementing a partisan two bill strategy. “I tried to work with Republicans, but they wouldn’t work with me. They left us no alternative but to use reconciliation to pass a new bill through the House and Senate on a majority vote.”

- If this is the primary purpose, then the meeting is not about the substance, but instead about Democrats trying to make Republicans look unreasonable to influence press coverage and public opinion, and to calm Congressional Democrats as they embark on a risky partisan legislative path. This is a cynical view of a potentially important meeting.

- If he thinks no Democrat-only bill is possible, and if he thinks no Republicans can be brought around to support a bill, then he may be looking to set up Republicans as the fall guy for his exit strategy. Liberals will be furious if the President, Speaker Pelosi, and Leader Reid abandon their efforts to pass legislation. If he can somehow shift the blame to Congressional Republicans, then at least he gets an election-year benefit from legislative failure.

- I don’t think this works because everyone knows that two Democrat-only legislative options exist: (1) the House could in theory pass the Senate-passed bill, or (2) the two bill strategy can be implemented using the reconciliation process. If the Democratic votes are there, either option works procedurally, even in the face of unanimous Republican opposition. If he cannot pass a Democrat-only bill through the Congress, it would again be because he could not hold 218 House Democrats and 50 (+VP) of 59 Senate Democrats. This procedural reality makes it hard to credibly blame Republicans for not getting a signed law.

- He may want to begin legislative negotiations with Congressional Republicans.

- If this is his goal he is going about it all wrong. The invitation letter sets up a structure of confrontation and nowhere mentions bipartisanship, inclusion, or compromise. The tone of the letter is horrible. It reads like an invitation to a televised debate rather than an attempt to find common ground. In parallel to the meeting, Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid continue to work behind closed doors to build a Democrat-only substantive compromise and procedural path, causing key Congressional Republicans to suspect the Blair House meeting is either meaningless or a trap. Leader Reid scuttled a bipartisan Baucus-Grassley “jobs” bill compromise late last week, further undermining any remaining Republicans who might try for a compromise. If the President hopes in this meeting to foster bipartisanship on health care reform, he is setting himself up for failure.

- Yes, this perspective is skewed based on my partisan affiliation and policy views. Even if you believe the lack of bipartisan progress so far is entirely the fault of Congressional Republicans, that does not change the reality that Republicans are approaching this meeting convinced that it is a confrontation or a trap. Whomever you choose to blame for that, the setup of the meeting discourages anyone in either party who might be interested in building bipartisanship. I see almost no possibility that bipartisan progress results from this debate.

- He didn’t have a specific game plan when he announced the invitation, but he knows he performed extremely well when he sparred on camera with House Republicans a few weeks ago. He is recreating a similar environment, one even more favorable to his strengths. Whatever his goal, he knows that a partisan conflict in this environment will likely play in his favor on camera.

- This seems like the most reasonable explanation.

The President’s new proposal

The invitation letter from White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel and HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius says the President will “post online the text of a proposed health insurance reform package.” House and Senate Democratic leaders have so far been unable to negotiate a compromise. What will the President propose?

- If there is a Pelosi-Reid-Obama substantive deal by the 25th, then it’s easy and ideal from the President’s standpoint. He can tell the Republicans, “Here’s the deal. I’ll tweak it for you to get your support. Otherwise we’ll pass it with only Democratic votes using reconciliation.” Democrats have so far been unable to close such a deal and round up 218 + 50 votes for it. I’ll give them a 3-5% chance of success before the 25th. It should be lower, but I think they deserve some credit for bull-headed perseverance.

- If there is not a Pelosi-Reid-Obama agreement by the 25th, then what will the President propose?

- Something midway between the House-passed and Senate-passed bills? If so, then Republicans can just reject it (easy for them, since they opposed both endpoints of that negotiation) and turn the focus back to disagreements between Pelosi and Reid. In the meeting Republicans could ask Congressional Democrats if they support the President’s new proposal and if they have the votes for it, and likely watch it break down in intra-party squabbling.

- The President could make concessions to Republicans in his proposal, even if they are only token concessions. In doing so he would risk angering Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid, whose help he needs to pass a bill.