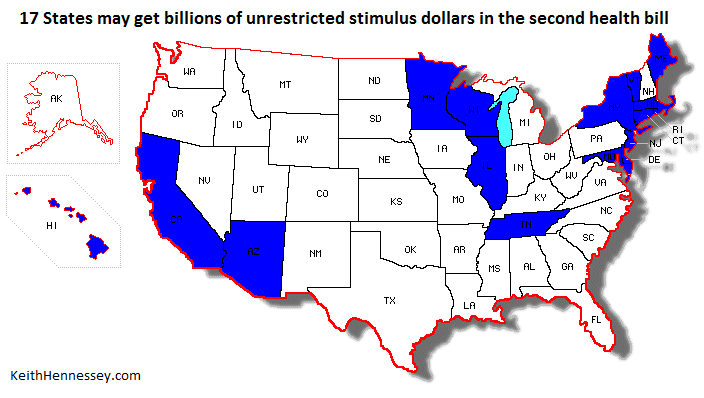

The second health bill contains billions in stimulus funding for 16 States & DC

The two pending health bills are about health care and expanding health insurance coverage. They’re not about fiscal stimulus, nor about building highways, hiring teachers, or cutting State taxes.

Right?

Then why does the second health care bill provide sixteen States and DC with billions of dollars in unrestricted funding, spending which would produce no change in health insurance enrollment?

According to the description of the new second health bill just released by Congressional Democratic Leaders, sixteen States and DC will receive billions of new dollars that they will be able to use for any purpose. This funding is, in effect, fiscal stimulus, and will not expand health insurance enrollment.

This may sound crazy, but it’s a semi-logical overreaction to the Nebraska-specific Medicaid earmark in the Senate-passed health bill. In an attempt to provide equity, the new second health bill would give 16 States and the District of Columbia billions of dollars they could spend on purposes other than health care.

In all 50 States and DC, Medicaid provides health care for low-income moms and kids, as well as for low-income and some middle-class elderly and disabled people. The law requires States to cover these mandatory populations.

The law makes other populations optional for States. If a State chooses to cover an optional population, the feds pick up part of the cost. This means that Medicaid is really 51 different programs, with some States covering a much broader group of people than others. The optional population we’re interested in are low-income adults, with or without kids.

Medicaid is a shared federal-State financing arrangement. On average the federal government pays 57 cents of every Medicaid dollar spent, and the State kicks in the other 43 cents.

This federal match rate varies from one State to the next, based on a complex measure of the State’s relative wealth. Relatively wealthy States like New York and California have a federal match rate of as low as 50 cents federal. In a relatively poor State like Mississippi the feds pick up 85 cents of each Medicaid dollar spent.

The Senate-passed health bill contains te now infamous “Cornhusker kickback.” As Nebraska expands its Medicaid program to cover low-income adults, this provision would permanently raise Nebraska’s federal match rate for the cost of these new enrollees. In effect, taxpayers in other States would pay higher taxes to help pay for the cost of expanding Medicaid coverage in Nebraska, above and beyond the share they, through the federal government, would normally pay. This means that as Nebraska expands its Medicaid program to cover low-income adults, the State would get about $100 M more each year from taxpayers in other States, forever.

Thanks to citizen blowback, Congress has decided that Nebraska should not get a special deal. But rather than just eliminating this increased spending, it appears the new legislation will expand this provision to cover all States. It appears the new reconciliation bill will force taxpayers around the country to further subsidize any State that expands its Medicaid population to cover low-income adults, increasing the federal match rates paid in those States. If this is in fact in the second health bill, it’s expensive.” CBO says the full incremental cost of those expansions would be $35 billion over ten years. Since a broad-based expansion won’t cover all the costs, it’s an unknown fraction of that amount, but it’s still billions of dollars.

“Hold on just a minute,” says California. “We expanded our Medicaid coverage years ago. We’re already covering the low-income adults that you feds are bribing paying Nebraska and other states to now cover. Why should they get a higher federal match rate than we do to cover the same eligibility group? That’s not fair. We should get a higher match rate too if we’re already covering those people.” Fifteen other States and DC chime in, “Yeah, me too.”

The President’s pre-Blair House proposal therefore included the following language on page 9. I have emphasized the key language in red:

Improve the Fairness of Federal Funding for States. States have been partners with the Federal government in creating a health care safety net for low-income and vulnerable populations. They administer and share in the cost of Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The Senate bill creates a nationwide Medicaid eligibility floor as a foundation for exchanges at $29,000 for a family of 4 (133% of poverty) – and provides financial support that varies by State to do so.

Relative to the Senate bill, the President’s Proposal replaces the variable State support in the Senate bill with uniform 100% Federal support for all States for newly eligible individuals from 2014 through 2017, 95% support for 2018 and 2019, and 90% for 2020 and subsequent years. This approach resembles that in the House bill, which provided full support for all States for the first two years, and then 91% support thereafter. The President�s Proposal also recognizes the early investment that some States have made in helping the uninsured by expanding Medicaid to adults with income below 100% of poverty by increasing those States’ matching rate on certain health care services by 8 percentage points beginning in 2014. The President’s Proposal also provides additional assistance to the Territories, raising the Medicaid funding cap by 35% rather than the Senate bill’s 30%.

Congressional Democratic Leaders have now released a description of their second health bill. It appears to parallel the President’s proposal in this respect:

- Repeals the special FMAP for Nebraska and changes the formula for calculating the amount of increased FMAP that will be paid to states that had, prior to enactment of the Act, expanded Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes up to 100% FPL

So California, which already covers low-income parents, would, under the President’s proposal, see their federal match rate “on certain services” increase from 50% federal to 58% federal beginning in 2014. Depending on how “certain services” are defined, for a State as large as California that could mean billions of additional federal dollars over time. California’s MediCal program spent $36 billion three years ago, and is certainly spending more today. A small percentage increase in the federal match rate could therefore mean a lot of new money for California. We can’t tell how much until we see legislative language.

Twelve States including California already cover low-income parents. Another five also cover low-income adults without kids. The President’s language covers both groups. We don’t know what the second health bill will do, so I will describe the effects of the President’s proposal. The seventeen States are: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Delaware, DC, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

In the second health bill the equity argument raised by the Nebraska-specific fix is addressed completely, but at the cost of enormously reduced efficiency. These seventeen States would receive billions of additional federal dollars for doing what they are already doing. These new federal dollars would supplant State dollars spent on Medicaid.

While this new federal money would be labeled “Medicaid,” those billions of extra federal dollars for covering no more people would free up the same amount of State dollars, which could be used for any purpose. A budget expert would say “All money is fungible,” and would label this federal windfall as a general revenue transfer from the federal government. In common parlance, this is billions of dollars of fiscal stimulus for sixteen states and DC, paid for by taxpayers in other States. It would have no effect on health care coverage or on any health care program. The only differences between this new spending and the fiscal stimulus enacted last February are that this money would be unrestricted in its use, and, depending on the legislative language, it could be a permanent subsidy to these 17 States rather than a one-time stimulus.

California has a $7 B budget gap to close this year and a $14 B gap to close next year, so I’m sure these funds would help. Sixteen other States could use this ongoing stream of unrestricted extra money for any purpose. They could build roads, improve their schools, or hire more State employees. They could pay down debt, increase State government spending, or cut State taxes. They could use these taxes paid by residents of other States for policy improvements or for pork projects.

While I appreciate the equity argument made by these 17 States, I don’t think we can afford to give them billions of dollars of unrestricted funds. Taxpayers have already ponied up more than $800 B in last year’s fiscal stimulus law, and tens of billions more in other legislation.

Even more importantly, Members and the American people think these are health care bills, not another fiscal stimulus. Few Members of Congress understand they may vote for a bill that would provide 16 States and the District of Columbia with billions to spend on things unrelated to health care.

It’s easy to understand why those trying to assemble a 216 vote coalition might have made this compromise. Yet the result conflicts with a common understanding about the purpose of the health care bill. This legislation has not been advertised as a targeted fiscal stimulus for certain States. This funding should be removed from the second health bill.

The inside game

Yesterday I guessed a two in three chance the President would have legislative success, which I now define as at least signing the Senate-passed bill into law.

In the past I have at least been able to fool myself into thinking there was a rational basis for my projections. Now I’m just guessing. I will stick with two in three for the moment, but I am now just picking numbers out of thin air based on some slightly informed guessing. This prediction will be out of date by tomorrow, if not sooner. And I do not anticipate updating it.

That’s because this is now entirely an inside game into which I have extremely limited visibility. If the Speaker can get 216 votes for two bills, then it’s over. But only a handful of people really know how far she is from that goal.

Since I cannot offer you genuine insight, I hope some broad observations will suffice, informed largely by my experience working for the best vote-counter in Senate history, Trent Lott. Senator Lott once said to me, “Keith, I know you were a math major. I’m going to teach you how to count.”

I hope you will accept these dozen observations in lieu of a real prediction.

- The President and Democratic Congressional leaders have created an external appearance of momentum. That is necessary but not sufficient for legislative success.

- Public expressions of confidence mean little. Democratic Leaders have to predict success whether they believe it or not, because those predictions affect momentum.

- For some Members the substance matters. (I know, that sounds terrible.) We have not yet seen the text of Bill #2 or CBO scoring of it. Additional risk will be introduced as soon as those become public, probably within the next 36 hours. How many times so far have we seen CBO scoring trip up the majority?

- There is a huge difference between needing 1-4 votes and needing 8-10 vote. I don’t know which she is really facing.

- Effective vote counters pick up the easy votes first, so by this time each additional vote is nearly intractable.

- Sometimes you bring a bill to the floor a few votes shy, thinking you can close those last few votes only when the vote is occurring. That’s a huge gamble. You do it only when you have no better option.

- Senate Democrats are an underappreciated wildcard, as is the Byrd rule. Will Senate Democrats blindly accept the substance of Bill #2, or will they try to amend it before passing it? Can Senate Republicans use the Byrd rule to force a change and therefore another House vote? Because of these wildcard factors, House Democrats should be asking their leaders if they might have to vote again on Bill #2 after the Senate considers and possibly changes it, and maybe after the Easter Recess.

- I wish I knew how well the House and Senate Democrats are coordinating. I imagine the trust and execution gaps on Bill #2 are among the largest hurdles the Speaker faces. If they are poorly coordinated, then I would expect some bumps once the legislative text is revealed.

- The Saturday vote target is irrelevant. They will slip it as needed.

- If the House passes Bill #2, assume 3 days minimum for Senate consideration. The motion to proceed is non-debatable, so that takes only 20 minutes for a vote. Twenty hours of debate typically takes two full days, plus one more for the vote-a-rama. House passage this Saturday would allow plenty of time for Senate consideration of Bill #2 and for completion of both bills if the Senate does not amend Bill #2. If the Senate does amend Bill #2, then the time for a second House vote on Bill #2 could bump up against the recess deadline. Of course, in this scenario Bill #1 is already on the President’s desk.

- At least as of 2008, the phones still worked on Air Force One. I believe they have working phones in Indonesia and Australia as well. The President’s trip delay is much more about the optics of him being here (or more accurately, the downside optics if he were not here) than about his practical ability to influence votes.

- So much for transparency. Bill #2 is being drafted in the Speaker’s office. So much for regular order in the legislative process, or open debate, or amendments. As recently as two weeks ago the President was admitting that they “could have done better” on transparency. We will never know the extent of side deals being cut to lock down votes, since many of them will be delivered outside this legislation.

Your guess is as good as mine.

(photo credit: firefighter training… by foreversouls)

Will the House follow the President’s demand for an up or down vote?

Here is the President, speaking in Strongsville, Ohio yesterday:

So, look, Ohio, that’s the proposal. And I believe Congress owes the American people a final up or down vote. (Applause.) We need an up or down vote. It’s time to vote.

This “up or down vote” language was originally interpreted to mean that the Congress should use the reconciliation process to avoid the possibility of a filibuster in the Senate. “A final up or down vote” means a vote on final passage, and that usually refers to a roll call vote on final passage, in which each individual Member casts a vote aye or nay.

Yet as the House approaches votes, possibly as soon as Saturday, the President’s words can have another unintended meaning. While the President is calling for “a final up or down vote,” the House majority is reportedly considering a legislative procedure which avoids just that.

The ranking Republican member of the House Rules Committee, David Dreier, has produced the best description and analysis I have seen of the procedural options. Rather than attempt to reinvent the wheel, I will just point you to his memo: The Slaughter Solution: Bending the Rules Beyond Belief.

Some, including Judge Michael McConnell, suggest that the deeming process being considered is unconstitutional. In the past the Court has been unwilling to “look behind the enrollment.” In effect, the Court does not analyze the process by which the House or Senate gets to a bill enrolled by the Speaker and the Senate’s President Pro Tempore. As I understand it, the Court considers legislative and voting processes pre-enrollment to be internal matters of the House and Senate that are not subject to Court review.

While regular readers know I am happy to delve into procedural details when they are outcome determinative, in this case I think they are a secondary issue. I assume the Speaker and Senate Majority Leader have a high probability of finding a procedural path to enactment, if they can find 216 and 50 votes for two substantive pieces of legislation.

At the same time, it says something significant when, to have a shot at getting those votes, both leaders feel they must push legislative procedures to their breaking point. This should be a warning sign: our democratic system is telling you to back off.

Rarely do you hear the argument that these bills represent good policy. Instead you hear that “this is an historic moment,” without much argument for the specific policy changes that would result. Health reform is not an ambiguous concept. It is now a massive set of proposed changes to one-sixth of our national economy. I think it’s terrible that 216 Members might be willing to try to enact this into law without the courage of taking a specific recorded vote. If these are good policy changes, then vote proudly. If your constituents disagree with you and might vote you out of office, but you feel that these policies are nevertheless deserving of your support, then say that, vote, and bear the consequences of that vote in November.

Deeming passage is trying to have it both ways – getting the policy and political outcome you desire, while trying to avoid the negative personal consequences of a recorded vote. That’s irresponsible.

The President says Congress owes the American people a final up or down vote. Will the House give it to them?

(photo credit: Nancy Pelosi)

ObamaCare vs. the Fiscal Responsibility Commission

Today I think health care reform legislation has about a two in three chance of being enacted into law. The legislative dynamic is volatile and my estimate changes at least daily.

For this post let’s assume for a moment that the President is successful, and that he soon signs two health care reform bills into law.

The President has created a Fiscal Responsibility Commission by Executive Order. That Commission is supposed to report its recommendations by December 1, 2010.

Part of that Commission’s Presidential mandate is:

<

blockquote>

The President is pushing for enactment of a large new health entitlement. In addition, the pending legislation would slow the growth of Medicare and, to a lesser extent, Medicaid spending. It would also raise taxes.

CBO says the new health entitlement would be more than offset by a combination of the “reductions” in Medicare and Medicaid spending and the proposed tax increases. I think CBO is wrong in their long run estimate, but will set that aside for this discussion.

Problem: Those “reductions” in Medicare and Medicaid spending are from an unsustainable trend, what budgeteers call an unsustainable baseline. The growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending are, along with Social Security spending growth, the main drivers of our long-run fiscal problem.

If the pending health bills are enacted, I anticipate their repeal will be topic A for the Fiscal Responsibility Commission. It’s an obvious starting point for the new Commission.

Actually, a better long-term fiscal policy solution would be to leave the “offsets” in place and just repeal the new spending promises. Pocket the enacted Medicare and Medicaid savings for deficit reduction (some would include the tax increases as well) as an initial down payment on our long-run fiscal problem, and just repeal the deficit-increasing portions of the new laws.

This is a different view from that of some Congressional Republicans who have argued that the Medicare savings in the proposed legislation are too harsh. I’d save even more money if I could (albeit in a different way), I just wouldn’t spend the savings on a new entitlement program.

Of course if you were to repeal the new health insurance subsidies, then the individual mandate becomes unaffordable for millions of individuals and families in the rough middle of the income distribution. If the subsidies were gone, Congress would be unwilling and unable to sustain the mandate. You’d have to repeal that.

And without the mandate, guaranteed issue and community rating wouldn’t work. (Some would argue that the mandate is so weak that they won’t work even with the proposed mandate.)

Repealing one trillion dollars of new federal commitments over the next decade, and even more beyond that, would be a great first step for a Fiscal Responsibility Commission. And since those promises aren’t scheduled to be delivered for at least four more years, you wouldn’t be taking something away from people who are already receiving the benefits. This would make repeal a smidge easier politically.

I hope that the pending health legislation is not enacted into law. If it is, fiscally responsible legislators, including those on the new Fiscal Responsibility Commission, should include in their formal recommendations repeal of all the deficit-increasing provisions of these new laws.

A similar argument could be made for the Medicare drug benefit, or for almost any previously-enacted entitlement expansion. I think there is a practical political and legislative difference between a benefit that has been enacted and promised but is not yet being delivered, and one which is already delivering benefits. It’s easier to “cancel” a new health insurance entitlement scheduled to begin 4-5 years from now, than to “repeal” or dial back a Social Security or Medicare benefit being received today by millions. (For the record, I’m quite open to all of the above.)

The President boxes himself in

Six of the 18 members of the Fiscal Responsibility Commission are current Republican members of Congress: House Members Dave Camp, Jeb Hensarling, and Paul Ryan, and Senators Tom Coburn, Mike Crapo, and Judd Gregg.

If these health bills are enacted, I expect all Congressional Republicans will vote no on final passage, including the six listed above.

I assume those six Members of the Commission will push for something like what I describe above. My proposal should not surprise anyone who gives it a moment’s thought. It’s the obvious first step.

The President and his team have admirably maintained complete flexibility on what the Commission should consider. All options are on the table, they say, and it’s not our job to take options off the table. Kudos to the Administration for doing this, especially when they will have AARP & Friends pushing them to rule out changes to major entitlement programs.

But how does the Administration answer the following questions:

The Administration has said that all policy options are on the table for the Fiscal Reform Commission. Would that include repeal of all or part of a new health care reform law or laws?

Is repeal of the proposed trillion dollars of new entitlement commitments over the next ten years, and even more beyond that, an option that the President’s Fiscal Reform Commission should consider?

Wouldn’t repeal of the new entitlement, while leaving the deficit-reducing elements of those bills in place, be a significant first step toward closing our long-term fiscal gap?

I expect Administration spokespeople would try to duck these question by saying the legislation as a whole reduces the deficit in the short-run and the long-run. If given, such an answer would be nonresponsive, because the question is instead whether the President is willing to consider recommendations to repeal only those parts of (hypothetical) new laws that would increase the deficit.

I can easily imagine the Commission breaking down over this question even before it gets off the ground. The President and Congressional Democrats would not want to give up their hard-won victory (if they achieve one) so quickly, and Republicans would insist on it as part of any long-term deal.

If I’m right, then one side effect of enacting the pending health care reform legislation would be to reduce the probability of a successful Fiscal Responsibility Commission.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Craig Kennedy)

Can House Democrats trust the Senate?

Can House Democrats trust the Senate not to foul up a two-bill strategy for health care reform?

No.

While most of the public discussion focuses on the procedural challenges particular to reconciliation, a more important point is being overlooked. The hardest part of the Pelosi/Reid strategy is trying to enact one massive package of legislative changes, spread out over two separate bills, one of which cannot change. Reconciliation is just the icing, and in some ways, reconciliation makes a two bill strategy easier since it avoids the filibuster threat.

The MSM has picked up on the sequencing challenge. For Bill #2 (the new reconciliation bill) to be scored properly for Senate consideration, Bill #1 (the original Senate-passed bill) has to have passed both the House and the Senate. But this means that House Democrats would have to vote for Bill #1 before knowing that Bill #2 would make it to the President’s desk.

This is being framed as a “trust” issue. Can House Democrats trust Senate Democrats to pass Bill #2 and send it to the President? After all, we know those Senate Democrats were happy to stop work with Bill #1, since that was their original bill.

This lack of trust is reinforced by centuries-old institutional tensions between the bodies, and by comments like Leader Reid saying at the recent Blair House summit that no one is talking about reconciliation.

In theory the trust issue is a solvable problem for Democrats. If a substantive agreement can be worked out, Leader Reid can make public procedural commitments, either on the Senate floor, in writing, or in person to wavering House Democrats. Leader Reid could be invited to speak to a House Democratic Caucus meeting and provide in-person reassurances. The President could reinforce such a Reid commitment. The lack of trust between Members of the same party but different Houses of Congress is a difficult but not insurmountable problem.

And yet nervous House Democrats have a right to be nervous, because while Leader Reid can make certain procedural commitments, he cannot guarantee, in advance, Senate passage of a bill without any modifications. At a minimum, House Democrats who embark on the two-bill strategy place themselves at risk of having to vote on Bill #2 a second time after spending Easter Recess back in their districts. This provokes the somewhat surreal follow-up question: Can House Democrats trust themselves?

Let’s assume the Speaker somehow rounds up the 216 votes she needs for a substantive package. Assume that package is drafted so that Bill #1 will pass the House unchanged first, and all the modifications will be in Bill #2, drafted as a reconciliation bill, to be passed first by the House and then by the Senate.

Let’s further assume the House passes Bill #1 and Bill #2 before the Easter Recess, scheduled to begin sixteen days from now, on Friday, March 26th.

Bill #1 is now ready to be sent to the President. Bill #2 goes to the Senate as a reconciliation bill. (Q: For how long can the Speaker hold Bill #1? Can she hold it forever if Bill #2 does not become law?)

Leader Reid, carrying through on a hypothetical commitment made to House members, brings up Bill #2 and tries to pass it. Let’s further assume that he has at least the 50 votes he needs, in his pocket, for final passage. So assume we (think we) know that the Senate will pass a version of Bill #2.

I don’t think Leader Reid can guarantee that the Senate will pass Bill #2 without modification. And if a single word in Bill #2 is added, removed, or changed, then the House will have to vote on Bill #2 again.

I see three risks during Senate floor consideration:

- Senate Democrats may want to modify the substance of Bill #2, notwithstanding any commitment by Leader Reid to oppose all amendments. I believe Senate Democrats are generally comfortable using reconciliation as the process for consideration of Bill #2, Republican objections notwithstanding. But that does not guarantee that those Senate Democrats will oppose all amendments. It’s easy to imagine Senators saying they’re not just going to let the House write a whole new health bill without Senate input.

- Even if Leader Reid can exert effective party discipline/cohesion, Senate Republicans will be looking for vulnerabilities and offering amendments to try to pick off 10 Democrats and amend the bill. I expect it would be quite difficult to pick off that many Democrats in this type of situation. But suppose Bill #2 contains another Cornhusker Kickback? Do you think that Bill #2 will be entirely devoid of targeted “Member interest” items (read: pork) as Speaker Pelosi makes the deals she needs to make to get to 216? Are you certain 50 Senate Democrats would oppose a Republican amendment to strike the most vulnerable of such items? If Senate consideration of Bill #2 happens after the Easter Recess, this risk is even greater. People will have more time to scrub the bill for politically vulnerable special interest provisions, and pressure will have time to build on Senate Democrats to fix the worst problems in Bill #2.

- Even if Leader Reid can rally sufficient party discipline to defeat every Republican amendment, and he needs only 50 of his 59 Members to do so, he still faces a Byrd rule risk. If Bill #2 contains a single provision, or even part of a provision, that has no budgetary impact, then 41 Senate Republicans acting in concert can force it to be removed from the bill. If it’s something like the Stupak abortion language, such a change would have a profound impact on the strategy. Suppose, however, it’s a trivial change. Suppose there’s a study on asthma in the bill that comes over from the House. Striking that study with the Byrd rule will mean that the House and Senate-passed versions are different. This means the House will have to vote again on Bill #2.

- What if the schedule slips enough so that a second House vote on Bill #2 is after the recess?

- Are nervous House Democrats willing to place themselves in the position where they have to vote a second time for Bill #2, after a week of feedback and pressure from the people back in the district?

- Are those other House Democrats whose support for Bill #1 is contingent on Bill #2 also becoming law willing to trust that the differences in the two bills can be worked out, and more importantly that the House will again be able to pass Bill #2, after the Easter Recess?

Successfully executing a two bill strategy is hard. Even if Congressional Democrats can resolve their trust issues, no one can promise a successful two-bill outcome, especially if the strategy spans the Easter Recess.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Does the President’s budget increase the deficit or reduce it?

Team Obama says the President’s budget would reduce the deficit. CBO says the President’s budget would increase the deficit. What the heck is going on? Who is right?

Let’s use Budget Bubble Graphs to see if we can understand what’s going on.

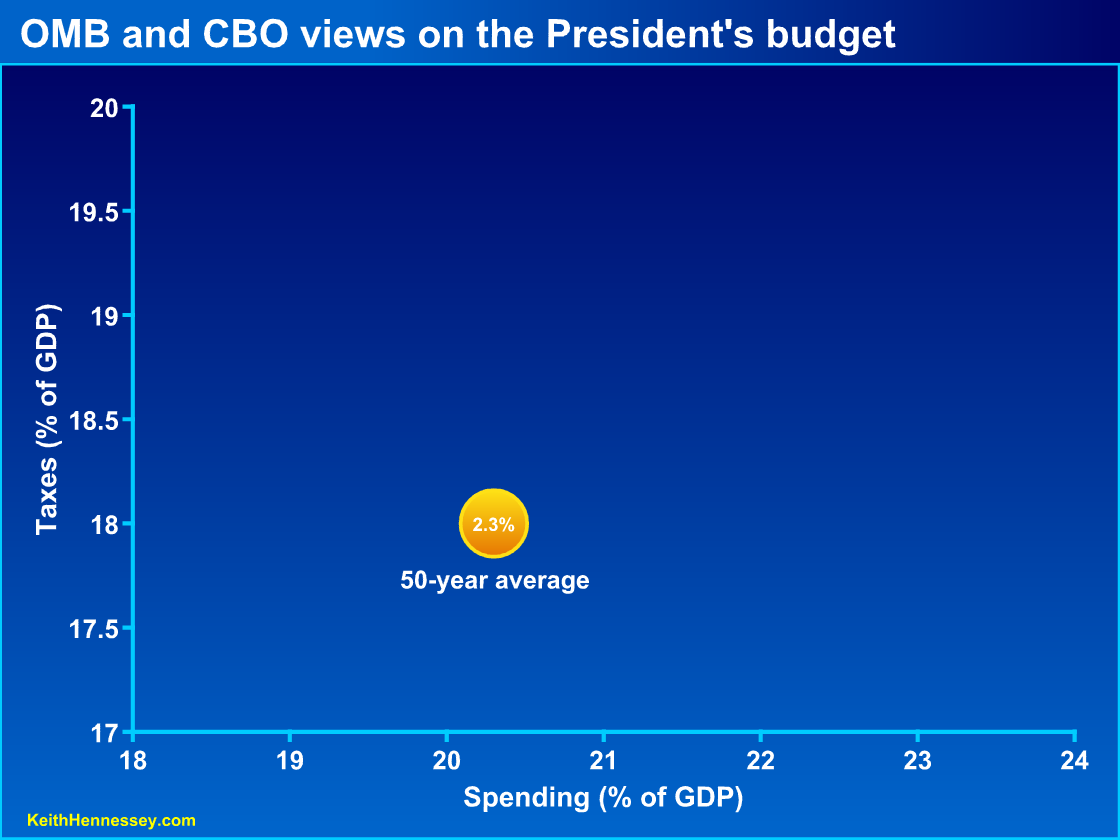

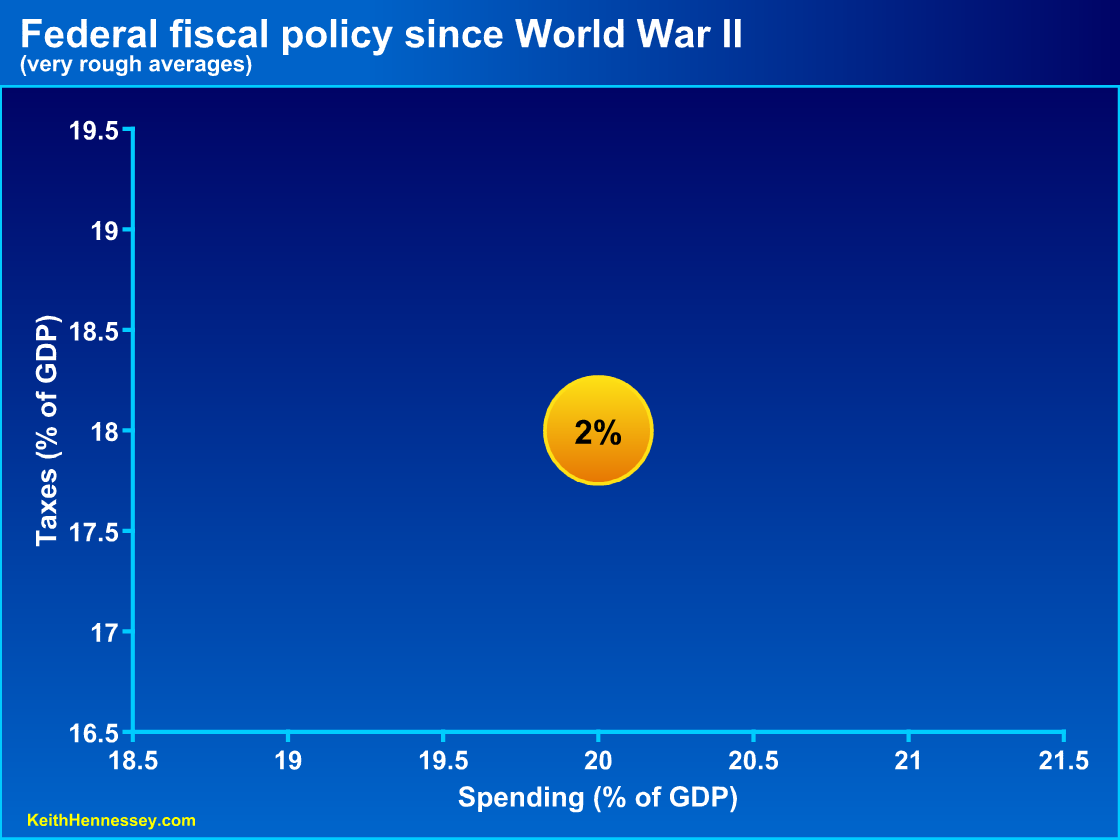

We begin by reminding ourselves that federal spending, taxes, and budget deficits have remained surprisingly stable over time. Over the past fifty years the federal government has, on average:

- taken 18.0% of GDP in taxes;

- spent 20.3% of GDP; and

- run a deficit of 2.3% of GDP.

While there are annual fluctuations and short-term trends, these long-term averages are incredibly stable. I believe they represent a sort of implicit political consensus about the appropriate role of government in American society, or at least a roughly stable political balancing point.

One lonely bubble

Here is that 50-year average on a simple Budget Bubble Graph. As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

As a reminder, the 20.3% of spending is plotted on the x-axis. This 20.3% of spending must be apportioned between current taxes and deficits (= future taxes). On average, we have collected 18.0% in current taxes, which we graph on the y-axis. The 2.3% average annual budget deficit over the past fifty years is represented by the size of the bubble. That size won’t mean much until we have another bubble for comparison.

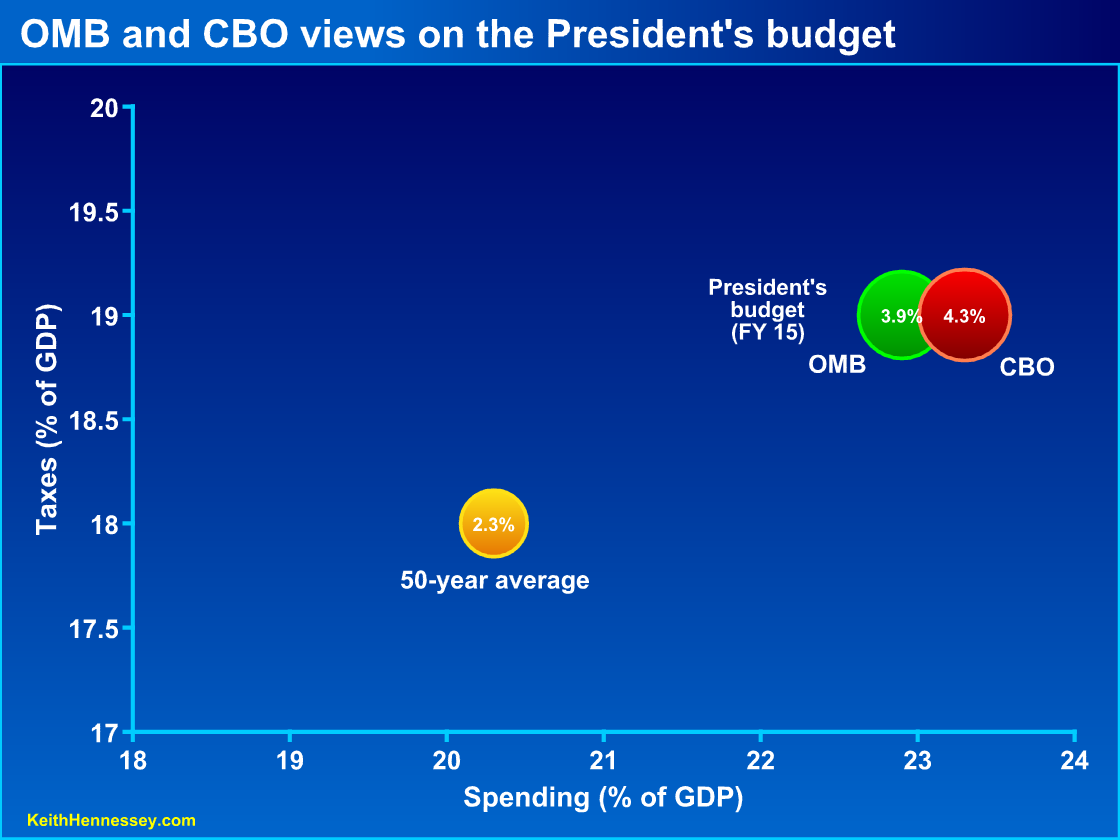

OMB and CBO agree on the results of the President’s budget

Let’s look at what the President’s Budget would do in 2015. I choose this date for several reasons:

- It’s far enough into the future that the after effects of the financial crisis and the recession are assumed to have worn off, so we’re looking just at desired policy in an assumed healthy economy.

- The President has chosen 2015 as a target date for his fiscal commission’s short-term goal.

- Five years out is a nice round number.

I hope you’ll trust that I am not cherry picking a year to make the numbers look bad. You can find all the data I have used here, here, and here.

Let’s add two more bubbles. Each represents scoring of the President’s proposed policies for 2015. The green bubble shows OMB scoring, the red bubble shows CBO scoring.

Three things should jump out at you:

- The red and green bubbles are nearly identical in size and location.

- They are both bigger than the yellow bubble.

- They are both right and above the yellow bubble.

The first observation (nearly overlapping red and green bubbles) shows us that OMB and CBO have nearly identical estimates of the spending, taxes, and deficits that would result from the President’s proposed policies:

- In 2015, the federal government would spend about 23% of GDP.

- That same year the government would collect 19% of GDP in taxes.

- We would run a budget deficit near 4% of GDP.

The second observation (red and green bubbles are bigger than yellow) shows us that OMB and CBO agree that the President’s budget would, in 2015, result in budget deficits significantly larger than the 50-year historic average deficit. As a reminder, if the deficit is greater than 3% of GDP, the debt-to-GDP ratio will increase.

The third observation (red and green are right and above yellow) shows us that OMB and CBO agree the President’s budget would, in 2015, result in significantly higher spending and higher taxes than the 50-year historic average.

OMB and CBO agree that the President’s budget would in 2015 result in much more government spending, much higher taxes, and a much bigger budget deficit than America has generally experienced over the past 50 years.

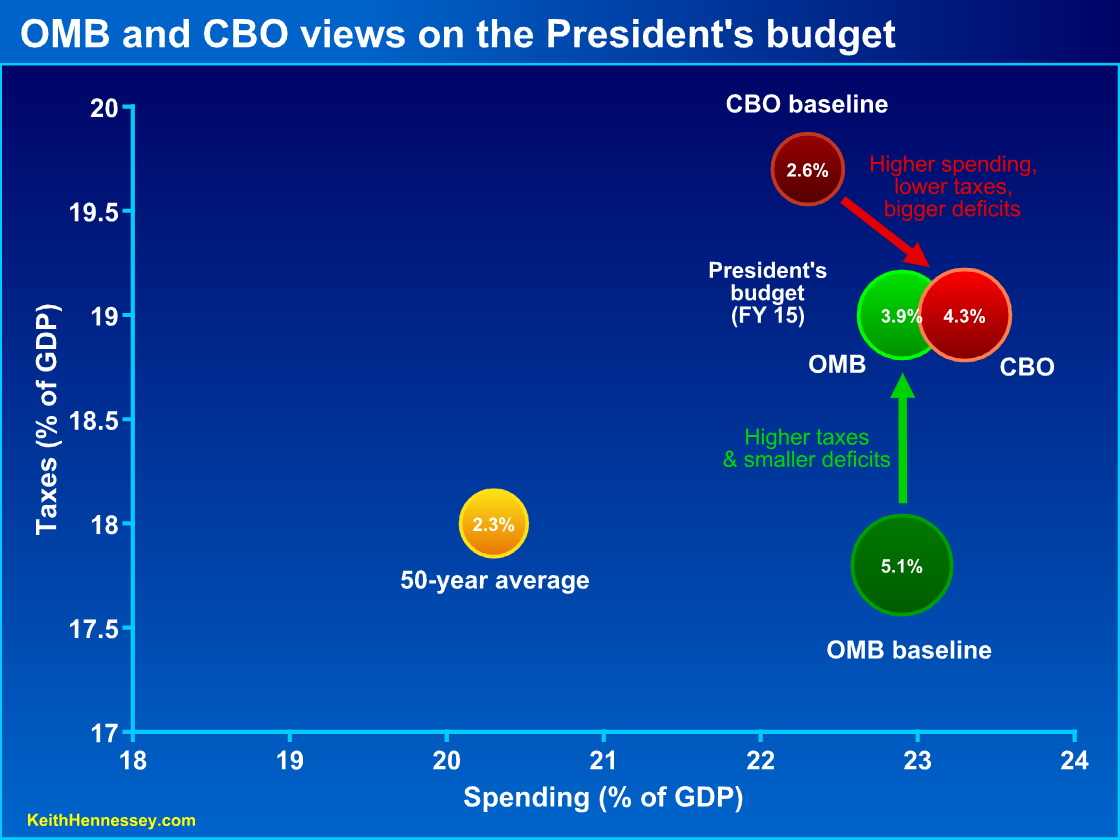

OMB and CBO disagree on the starting point from which changes are measured

While OMB and CBO end up at nearly identical ending points, they begin their measurement from different starting points.

CBO measures changes from a starting point of current law. Under current law the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of this year, the Alternative Minimum Tax is not patched, and Medicare per-service payments to doctors get cut this year and each following year.

OMB creates a “current policy” baseline as their starting point. They begin with current law but assume policy changes like permanent tax relief and a permanent change to Medicare payments to doctors. The OMB current policy baseline therefore assumes higher spending, lower taxes, and bigger deficits than the CBO baseline, which is why the OMB baseline bubble is below, right, and much bigger than the CBO baseline bubble.

OMB argues their baseline represents a more reasonable starting point from which to measure fiscal policy changes. Critics argue OMB is gaming the baseline to make their proposed policy changes look better.

CBO says the President’s budget moves fiscal policy from the dark red baseline bubble to the light red CBO score of the President’s budget. Using CBO scoring, we see that, relative to a current law starting point, the President’s budget increases spending (moves right), cuts taxes (moves down), and increases the budget deficit (bigger light red bubble).

OMB says the President’s budget moves fiscal policy from the dark green baseline bubble to the light green OMB scoring of the President’s budget. Using OMB scoring, we see that, relative to OMB’s definition of current policy, the President’s budget leaves spending constant (no horizontal movement), raises taxes (moves up), and reduces the budget deficit (smaller light green bubble).

Each characterization can therefore be defended, if you accept the two different starting points. And since very few people understand or care about the difference between a current law baseline and a current policy baseline, most people are just confused.

You can see how the common press focus on just the budget deficit would give an incomplete picture of reality. The bigger bubbles are an important and scary part of the story, but if you ignore the three percentage point increase in spending and the one percentage point increase in taxes, you’re missing the rest.

You can also see why a debate about the proposed change in the budget deficit would be confusing and apparently contradictory. Is a roughly 4% deficit in 2015 a reduction or an increase from what would otherwise be the case? It depends on your starting point.

My view

I question certain assumptions in the OMB current policy baseline but will set those concerns aside for now. Two advantages of the CBO baseline are that it has a stable definition over time and it is well understood by budget wonks.

Mostly I don’t care about these philosophical baseline debates or the political rhetoric that flows from them. The debate over the starting point and the direction of the policy change arrow matters less to me than where the resulting policy bubble ends up and how big it is. I care far less about how we label the proposed changes than I do about the proposed result.

There is no significant disagreement between OMB and CBO about the proposed result: the President’s budget would result in much higher spending, taxes, and budget deficits than America is used to.

I believe fiscal policy needs to pull the red and green circles left and down toward the yellow bubble. I don’t want bigger government. I’d like to move even farther left and down than the yellow bubble, but with this Administration I’d be quite happy to stick with the historic average.

Some of the movement rightward by 2015 is built into current law, a result of the three big entitlement spending programs pushing us ever farther right over time. You can see that because the CBO current law baseline bubble for 2015 is two percentage points right of the historic average. We need to change current law to prevent government from exploding in size. We’ll examine this in more detail in a future post.

I also believe that much of the negative political reaction we have seen from American citizens over the past two years is a gut reaction to the bubbles moving right and up and growing bigger. It is not just a reaction to bigger budget deficits. It is also an adverse reaction to bigger government, measured by more government spending, higher taxes, and bigger deficits.

Déjà vu all over again

This is like deja vu all over again. – Yogi Berra

A Republican on Capitol Hill points out that we’re going through a health care press coverage time warp. In each of the following four headline pairs, one is from this morning. The other is from last year. See if you can guess which is which.

Politico: President Obama takes reform on the road

AP: Obama takes health care pitch to people … again

Bloomberg: Obama Set to Fight “Uphill Battle” on Health Bill

Bloomberg: Obama to Appeal to Public on Health Care as Senate Struggles

AP: Obama’s health care pitch to Democrats: Trust me

AP: Obama makes last-minute appeal to Democrats for health care votes

AP: Obama to appeal for public support on health care

AP: Obama appeals for health care votes

Similarly, see if you can determine which headline in each pair is from 2010, and which is from 2009.

CSM: To pass healthcare reform, Democrats may go it alone

CNN: Democrats May Pass Health Reform without GOP Support

NYT: Obama Takes Health Care Deadline to Democrats

AFP: Deadline looming, Obama urges health care action

Boston Globe: Obama steps up health care pressure

Politico: President Obama steps up health care push

AFP: Obama presents make-or-break health reform plan

NPR: For Obama, Health Care Overhaul Is Make-Or-Break

AP: Top Dems looking to Obama for health care momentum

Reuters: Obama tries to regain momentum in healthcare debate

Reuters: Obama seeks momentum, funds for Senate allies

Reuters: Obama team tries to regain momentum on healthcare

CBS: Obama’s Health Care Push: The Race is On

WaPo: Obama Health Care Push Resumes This Week

AP: Obama turns up the heat for health care overhaul

AP: Obama expands health care push

HuffPo: White House, Dems, Plan For Make-Or-Break Summit

Bloomberg: Obama Sets “Make-or-Break” Deadline on Health Care

There are thirteen pairs in total. If you like you can post your score in the comments. No fair peeking.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Health care reform CPR

Can Speaker Pelosi bring health care reform back from the dead? Did it ever really die?

Doctors say that Nordberg has a 50/50 chance of living, though there’s only a 10 percent chance of that.

– George Kennedy as Ed Hocken in The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad

In addition to my last health care post, Nate Silver summarizes well the forces pushing in both directions. John Podhoretz also has a good strategic overview. I’ll add a few assorted observations to begin the work week.

Vote counting & strategy

- Focus all your attention on Speaker Pelosi’s attempts to get 216 votes. If she can lock them down I think there’s a four in five chance there will be a law (or two).

- The Stupak/abortion issue appears to be the biggest substantive hurdle. Chatter about a possible three bill strategy (!?) to address this is stunning. Two bills isn’t hard enough?

- The sequencing/trust problem still appears hard. How does the Speaker get her members to vote for Bill #1 based only on a promise that Bill #2 will make it to the finish line?

- Occasionally a Congressional leader calls a vote without having the votes locked up, in the hope that the pressure of a floor vote will help close those last few remaining holdouts. This is incredibly risky. Sometimes there is no better option.

Probabilities

- Public signs of optimism from the President, his team, and Democratic Congressional leaders tell us little. We don’t know if they actually think they will have the votes, or if they are asserting that to try to make it true. Imagine the impact if Speaker Pelosi were to tell the press “We might not succeed.” Doing so would further embolden those marginal Members she is trying to convince to vote aye. They are telling us they think they will succeed, but they have to say this whether or not it’s true.

- The President’s chance of legislative success is way above the 10% I projected shortly after the Brown election when I declared a comprehensive bill dead. Was I wrong, or have things changed dramatically? A little of both, I think.

- I underestimated the willingness of the President and Democratic Congressional Leaders to press forward against extremely long odds. They appear to be doing serious medium-term political damage to their party. They appear to be placing in jeopardy a fairly large number of their Members, which could damage the rest of the President’s policy agenda. They are directly contradicting their stated strategy of focusing on the economy. You decide whether this is principled persistence, a confident smart strategy based on superior information, a different assessment of the voters and the polls, or a pathological obsession with killing the White Whale at any cost. Call me Ishmael.

- I also underestimated the Democratic party cohesion under tremendous political pressure. Assuming they think they are doing the right thing, they are doing so at tremendous cost to themselves. I can’t figure out if most rank-and-file Democrats agree with their leaders’ strategy or are just afraid to buck it.

- As of this posting, Intrade estimates about a 50% chance of success. That seems a little high. I’ll guess it’s a coin toss as to whether the Speaker can round up 216 votes for two bills, multiplied by an 80% chance that if she does they can overcome other hurdles to get two signed laws. That puts me at a 40% chance President Obama gets to declare victory, but with lots of uncertainty.

- To those who think the probability is higher, remember that they have been trying to rally these votes for six weeks and have not yet succeeded. Each time I hear rumblings of a new strategy, I conclude only that Congressional leaders have decided that the last new strategy won’t work. Even if the Speaker and her team are maximally effective they may fail. Sometimes the votes just aren’t there, and you don’t know that until you have tried every path and failed, or you have decided the clock has run out.

- If there is a path to 216 votes, I am confident the Speaker will find it. She has a remarkable ability to bend her colleagues to her will.

Timing

- There are three full work weeks until the Congressional Easter Recess. Recesses can be delayed. I ignore the White House’s urgings to vote by the end of this week. They’ll vote when they think they can win, and not before.

- The conventional wisdom is that if they can’t get it done by Easter Recess, it will never happen, so they’ll give up. That feels right, but if the President wants to press forward after recess, nothing precludes him from doing so. I had mistakenly thought they would have given up long ago. I’ll guess that the real deadline is for House passage before the Easter Recess.

Process

- In response to comments on my procedural postsabout reconciliation:

- Concerns about a revenue measure precluding the Senate from going first are overstated. There are well-established and Constitutionally-consistent ways to work around that if necessary. Still, I expect the House to go first, so I think this is irrelevant.

- Yes, the Presiding Officer (the VP if he wants) can overrule the Senate Parliamentarian. Technically, the Chair rules after taking “advice” from the Parliamentarian. 99% of the time that advice is followed, but it’s up to the Chair. When that advice is overruled, it’s a well-coordinated exercise between the Presiding Officer, the Majority Leader, and sometimes others.

- I don’t know what would happen if Senate Republicans were to offer an extended sequence of amendments (hundreds) to a reconciliation bill. I agree with those who say that it’s possible the Chair would rule that such amendments are dilatory and sustain that ruling by a majority vote. This is a gray area.

- With all the attention focused on the House, some observers may be overlooking Senate challenges. Even if 50 Democratic Senators are willing to use the reconciliation process for a second bill, that does not mean they will necessarily accept a Speaker-drafted Bill #2 and pass it without amendment. Any Senate amendments must then either be accepted by the House or worked out in a conference. At a minimum this would slow the process down.

Republicans

- This is almost entirely a Democratic party exercise. Republicans have few procedural tools available to them. Their power lies mainly in their ability to influence wavering Democrats not to follow their party leaders. Leader Boehner and Leader McConnell have both been threatening/promising that they will keep health care front and center through November no matter what. This is an attempt to reinforce the political costs of an aye vote with those wavering Democrats. They want those Members to believe that an aye vote will cost them their seat in Congress. This is hardball strategy.

- The extended and public intra-Democratic party thrashing this month means that if legislation fails it will be difficult for Democrats to credibly blame Republicans for that failure.

- I agree with those who argue that using reconciliation in this case is an abuse of that process. This argument appears to have little traction with those swing Democratic votes, so I recommend opponents to the bill return to substantive concerns as their primary point of attack. Spend more of your time and energy explaining why this bill is bad policy. You don’t have to abandon the process arguments, but I think they are less effective than the substantive ones.

- Republicans should not use Medicare scare tactics as their primary weapon against this bill. There is a legitimate Medicare argument to be made, but many Republicans are instead following the easier, possibly more effective, but less responsible path of trying to scare seniors. We need to slow the growth of Medicare spending. We just shouldn’t spend the Medicare savings on a new entitlement. There are plenty of other effective lines of attack against these bills that don’t limit your ability to do good policy in the future.

- The McCain/Graham amendment to preclude changing Medicare in reconciliation was irresponsible showboating and a recent low point for Republicans in this debate. A primary purpose of reconciliation is to change large entitlement spending programs, including Medicare. At least the Senate didn’t vote on it during consideration of the extenders/jobs bill. I hope it never returns.

- Republicans were at their best in the Blair House debate. Let’s see more of that: floor speeches and press appearances explaining why these bills are bad policy.

The partisan strategic gap

I am struck by the enormous gap between the two parties on the strategic calculation being made by the President and Democratic Congressional leaders. If you set aside your policy views, do you think the current path makes strategic sense for the majority? Almost every Republican insider I meet shakes his or head in befuddlement and says no, I just don’t get why they’re doing this.

Dan Meyer was Speaker Gingrich’s Chief of Staff in the mid-90s, and later served as the head of Legislative Affairs for President Bush (43). He and I survived the 95-96 government shutdown conflict between Congressional Republicans and President Clinton. I worked for Senate Budget Committee Chairman Pete Domenici at the time. Dan made a comparison the other day. Imagine, he said, right after the government had reopened in January of 1996, after Republicans had been getting hammered every day for a month, if I had run up to you and said, “I’ve got a great idea! Let’s shut it down again!” You’d think I was crazy.

That’s what this feels like. The President and his allies could now quite easily enact a massive expansion of Medicaid and S-CHIP, paid for by a subset of the offsets in these bills. I would oppose such a bill, but it would be a legislative slam dunk with few political costs (for them) outside of a disappointed left wing. To my chagrin they might pick up a few Republican votes. And yet they press onward with a super-high risk strategy. This is a classic bird-in-the-hand tradeoff.

In addition to my policy problems with this bill, I too have difficulty understanding the continued push. In addition to our policy differences, I can think of four areas where my assessment might differ from that of the decision-makers:

- They may assess the probabilities of success differently. If estimate their strategy has only a 40% chance of success (and 10% six weeks ago). If they think their chances are twice as large, that changes the calculation. They have better information than I do about where the votes are, but they have not exactly been a model of legislative competence so far.

- They may assess the politics differently. The day after Senator Brown’s victory, Team Obama was on TV arguing that the voters did not reject the President, Congressional Democrats, their agenda, or their health care bill. Fine, they had to say that. Do they actually believe it? If so, they may believe that a signed law will cause the political damage to their vulnerable Members to diminish. (I don’t.) They may believe what they are telling those Members, that there is no individual political benefit from flipping aye to no. (I don’t, because you can now respond to the attack ads that will hit you.) If so, they probably assume that a signed law will help their Members in November.

- They may value the costs and benefits differently. They appear to be willing to place at risk dozens of Congressional seats from Members of their party for the possibility of achieving this one legislative goal. They may believe that the policy victory is worth those likely losses and the harm it will do to the rest of their agenda. If you focus only on health care policy this is principled persistence. If you look at health care as one part of a broad policy agenda, then it is a prioritization, in which they are sacrificing other policy goals for this one accomplishment.

- The leaders may be narrowly self-interested and able to exert tremendous party discipline on those with different interests. Legislative failure could harm a rank-and-file Democrat from a purple district, but it would be devastating to the President and the Speaker, who are judged on their ability to lead others. We know that some Congressional Democrats don’t like this bill as a policy matter. We know that some are afraid of the political consequences of voting aye. Yet many in both groups appear willing to vote aye.

(photo credit: Defibrillator latt by Olaf)

Health reform that would break the bank

Budget Director Peter Orszag and White House Health Policy Advisor Nany-Ann DeParle (who was a PAD in the Clinton OMB) write in today’s Washington Post:

But some critics complain that the administration has slipped in its commitment to fiscal responsibility in health reform.

These critics are mistaken. The president’s plan represents an important step toward long-term fiscal sustainability: It more than meets the president’s commitments that health-insurance reform not add a dime to the deficit and that it contain measures to reduce the growth rate of health-care costs over time.

I suspect this op-ed is aimed at moderate Democratic House members who are nervous about voting aye. I am one of the critics Orszag and DeParle mention, and I’d like to respond to one of their arguments.

CBO says the Senate-passed bill would reduce budget deficits over the ten-year period 2010-2019 by $132 B relative to what those deficits would otherwise be under current law. I want to focus on this comparison, and in particular on the $438 B of savings CBO scored from Medicare and Medicaid in that bill. I do not question these aspects of CBO scoring, but do disagree with the conclusions drawn from it by others.

$210 B of these $438 B in net Medicare and Medicaid savings come from a single legislative gimmick known as “gaming the budget window.” To a certain extent the Obama Administration isn’t to blame for this problem, but they are taking advantage of it in this legislation. This is a fairly complex technical issue, and by no means the only problem a fiscally responsible person should have with this bill. Still, $210 B and the Administration’s claim of fiscal responsibility rely upon this gimmick, so I’ll do my best to explain it.

Example:

- Your car has a 15 gallon fuel tank and you fill it up each week.

- For the past year gas prices have averaged $3 per gallon. Gas has therefore cost you $45 per week.

- Now gas prices spike upward to $4/gallon. You hear in the news that terrorists damaged a pipeline in Saudi Arabia that will be offline for a few days.

- Gas therefore costs you $60 this week.

- Experts say the price will drop back to $3 next week once the pipeline is repaired.

- So far so good. Now we start getting funky.

- Suppose you assume that gas prices will remain at $4 forever. You tell yourself you will spend $60 per week on gasoline forever. This isn’t true, but you tell yourself that it could be true if the pipeline is never fixed.

- Your family budget is constrained enough that you wouldn’t be able to afford this if it were to actually happen. If you actually had to spend $60 per week on gas and didn’t cut back elsewhere, you’d go broke. (Times are tight.) But you assume it anyway.

- After filling up today, you then decide that you will “cut” your gas price allowance from $60 per week to $45 per week for (only) the next month. You calculate you will “save” $15 per week for four weeks, or $60 over the next month.

- Having “saved $60 this month,” you immediately spend $50 on a new toy for yourself.

- You return home and tell your spouse “Honey, I bought this new $50 toy and saved $10!”

- The gas price returns to its historic average $3 per gallon, so you now hit your so-called $45/week budget target without actually having to cut your gasoline usage.

- That’s not all. One month from now, when prices are still at $3/gallon, you budget for the next month.

- You once again “cut your budgeted gasoline spending from $60 per week to $45” and “save another $15 each week for the following month.”

- Having “saved another $60” for the upcoming month, you buy another $50 toy and tell your spouse you once again saved $10 this month.

- Repeat the above until you go broke.

This is what happens in Medicare every few years. The Medicare law is written to assume that per-service payments to hospitals will increase each year by an index called the market basket. If payments were to actually increase at the market basket rate each year, they’d grow about 4 percent per year.

Instead, every 3-5 years Congress “cuts” payments to hospitals. They change the law to pay hospitals “market basket minus X” for, say, the next five years. “We’ll pay you market-basket minus 1 for the next five years,” Congress says. That’s roughly +3 percent more per service per year.

“Look!” Congress says to themselves. “We just saved billions of dollars! Let’s go spend it!” In the same law, they spend some of the “savings” CBO scored them with from “cutting” the hospital payment growth rate from 4% per year to 3% per year. They claim deficit reduction for the rest.

And when they write the law, they change it for only the next five years, because that’s the length of their “budget window” established by the budget resolution. The law they write says “Hospitals, we’ll pay you market basket minus 1 for the next five years, but we won’t change it beyond that. That means that six years from now, you’ll return to a market basket growth rate of 4% per year.

You can see it coming. Five years later, Congress returns and does it again. They face hospital payment updates of 4% per year for the indefinite future. They “cut” those payments to 3% for the next five years, spend some of the “savings” on program expansions, and claim they have reduced the deficit.

What I have described is not partisan. Both parties do this and have done this many times. And when they do, they are technically living by the scoring rules. Both parties game the budget window. Democrats tend to spend more of the “savings,” while Republicans tend to claim more of it as deficit reduction.

The policy reality is that, over time, Medicare payments to hospitals increase at an average rate of about 3%, or market basket minus one. Since Congress games the budget window and takes advantage of the scoring convention that deficit reduction is measured relative to current law rather than current policy, they create an environment in which they appear to be making hard choices while allowing themselves to allocate a new pot of money every so often for new spending and claimed deficit reduction.

As a budget policy matter, there are two bad behaviors here: (1) applying this gimmick temporarily and then repeating it; and (2) spending some of the money on new real expansions of government with real deficit costs, while claiming deficit reduction.

The Administration deserves credit in the Senate-passed bill for no longer doing (1). The Senate-passed bill makes permanent long-term reductions in the growth rate of Medicare payments to hospitals. They games the budget window, but only by a little bit. This is good and surprising. I also like the way they implement that change, by incorporating a productivity adjustment into the baseline growth rate for Medicare spending.

Unfortunately, they then take almost all of these long-term “savings” and re-spend them. This is what allows them to both create a massive new entitlement spending program, and claim CBO-scored deficit reduction relative to current law. In our example above, imagine if you agreed to permanently reduce your gasoline spending to $45/month. That would be good and reasonable. But suppose you also legally committed yourself to spending $58 per month for a new toy each month forever. That would be horribly irresponsible – you’d be guaranteeing that you go broke, all while pointing the $2 per month that you had “saved” as proof of your fiscal responsibility.

America’s primary fiscal problem is the long-term growth of health entitlement spending. The Senate-passed bill creates a commitment for a new health entitlement program, and takes advantage of a gimmick to claim that this commitment is paid for. Instead, this bill would guarantee a future fiscal crisis.

(photo credit: Break the Bank (6/365) by swimparallel)

Introducing Budget Bubble Graphs

Here is a typical public debate about the budget deficit:

Republican: Republicans are for smaller deficits. You Democrats just want to increase spending. Republicans want smaller deficits by cutting spending.

Democrat: Hypocrite. You Republicans increase deficits by cutting taxes without paying for them. And you don’t really want to cut spending. Democrats are for smaller deficits through a combination of responsible spending cuts and tax increases.

Republican: When was the last time you enacted or even proposed a net spending cut? Even when you do propose to cut spending, you just turn around and respend the money on some new government program. You just want to raise taxes, then increase spending, leaving deficits exactly where they are. Sometimes you don’t even bother with the tax increase, you just increase spending. We are the party of lower deficits.

Democrat: You mean, like you guys did with Medicare or you do with defense everyyear? We are the party of lower deficits.

< one shoves the other and all hell breaks loose >

This kind of argument contributes more heat than light, in part because it focuses only on deficits and ignores a major philosophical distinction between the two parties: different beliefs about the appropriate size of government.

I am going to do my best to illuminate this debate by expanding its scope and introducing a new kind of graph. I call it a Budget Bubble Graph.

If this goes well we can use Budget Bubble Graphs to better understand the fiscal policy debate in Washington. We can compare different budget proposals, analyze historic fiscal policy differences, and easily visualize the effects of various legislative proposals. That’s a lot of responsibility for a little graph. Today I’m going to introduce the graph format and begin to show how it can help you think about the above fiscal policy food fight. I anticipate using Budget Bubble Graphs a lot in future posts. Today’s post is therefore something of an investment for the future.

Introducing the Budget Bubble Graph

Bubble graphs are not new. They are a standard graph type, a useful way to show three dimensions of data on a flat chart. As far as I know, it is new to use them for the federal fiscal policy debate.

Let’s begin with the simplest possible graph. Since the end of World War II the federal government has, on average, spent a little more than 20% of GDP. Over the same time frame, it has financed this 20% by collecting a little more than 18% of GDP in taxes and borrowing the rest from future taxpayers, running an average deficit equal to about 2% of GDP. I’m going to round the numbers to 20-18-2 to make it easy. Frankly, the numbers matter little today. We’re just trying to get used to the format.

In each case you can click on a graph to see a larger version.

I want to point out a few subtle features about this fairly straightforward graph:

- I have put spending on the x-axis because that is the primary fiscal policy choice made in Washington: how much is the government going to spend?

- The secondary fiscal policy choice is: given how much we’re going to spend, how much of it are we going to tax now (y-axis) and how much are we going to borrow now (size of the bubble)? Whatever we borrow now we will have to collect in future taxes. Please think of deficits as equal to future taxes (with interest).

- That’s a deficit bubble equal to 2% of GDP. A bigger deficit would mean a bigger bubble.

- The 2% deficit bubble size is the difference between the amount we’re spending (20% on the x-axis) and the amount we’re collecting in taxes (18% on the y-axis).

- The bubble size is not to scale. If it were it would be much bigger. What matters for our purposes are the relative sizes of different bubbles. I tried scaling it to size and the graph became too cluttered.

Graphing the simplest possible fiscal policy changes

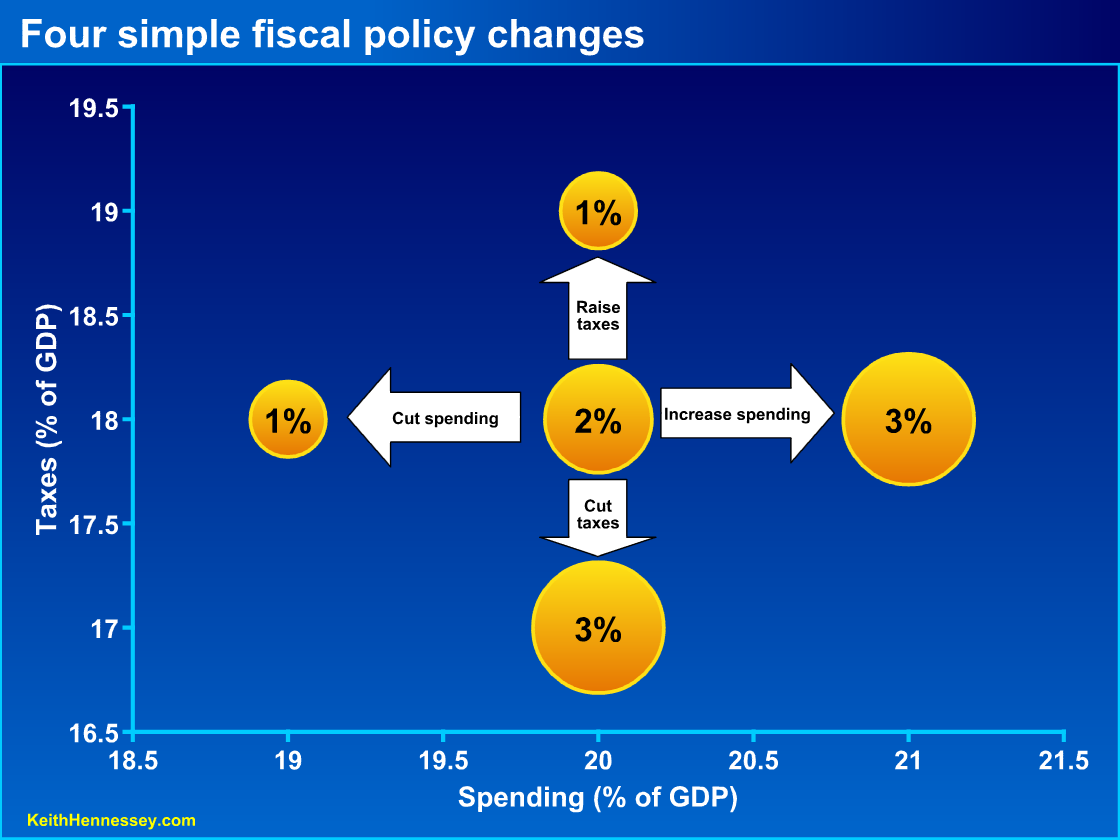

Now let’s look at the simplest possible fiscal policy changes:

- increasing spending by 1% of GDP;

- cutting spending by 1% of GDP;

- raising taxes by 1% of GDP; and

- cutting taxes by 1% of GDP.

Please pay attention to the effect of each policy change on the deficit.

Starting from 3 o’clock on the graph, if we raise spending from 20% of GDP to 21%, we move right on the graph. If we collect the same 18% of GDP in taxes (i.e., don’t move up or down), then we need to borrow 1% of GDP more, so our deficit bubble increases from 2% of GDP to 3% of GDP. (The relative areas of the bubbles are properly scaled.) Bigger bubble = bigger deficit = more borrowing now = higher future taxes.

Similarly, if we cut spending by 1% of GDP to 19% and hold taxes constant, we move left and reduce the budget deficit to the smaller 1% bubble at 9 o’clock on the graph.

You can see that if we change spending and hold taxes constant, the deficit changes to match the change in spending. The 3 o’clock bubble represents a deficit-financed spending increase. The 9 o’clock bubble represents a deficit-reducing spending cut.

Now let’s turn to taxes. Starting with the 12 o’clock bubble, if we hold spending constant at 20% and raise taxes by 1% of GDP, from 18% to 19%, we move straight up and reduce the budget deficit from 2% to 1% of GDP. This is a deficit-reducing tax increase. I think of this policy change as shifting the burden of financing a given level of spending from future taxpayers to current taxpayers. We get higher taxes now and lower taxes later.

Finally let’s look at the 6 o’clock bubble. If we hold spending constant and cut taxes by 1% of GDP, we increase the budget deficit from 2% to 3% of GDP. We are shifting the burden of financing a given level of spending from current taxpayers to future taxpayers.

Straightforward, no? Please note that this graph format is designed to be value neutral. It is simply an analytical tool.

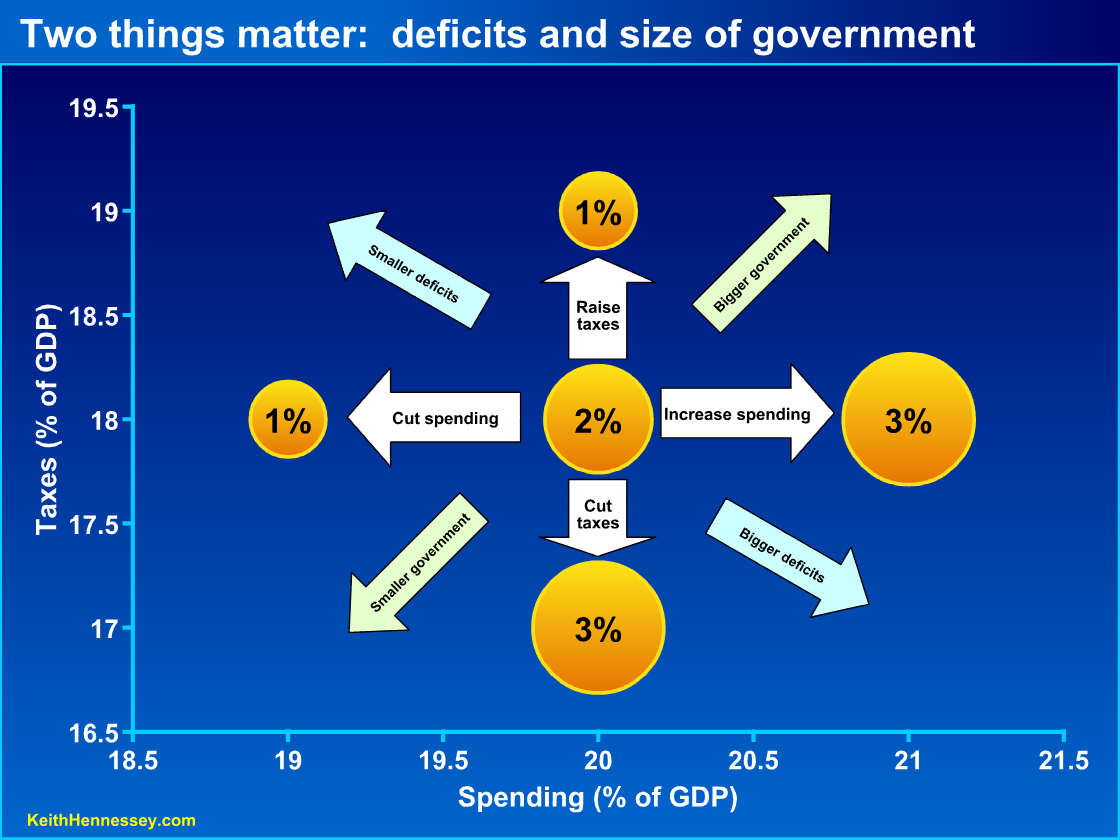

We care about deficits and the size of government

Let’s add one more layer of complexity. I am going to add four diagonal arrows to the above graph. Click the graph to see a bigger version.

You can see that as we move up and/or to the left, deficits get smaller. This makes sense – if we cut spending, raise taxes, or both, we get smaller budget deficits.

Deficits get bigger as we move down and/or to the right. If we increase spending or cut taxes, we get bigger budget deficits.

Moving up and/or to the right represents bigger government, and moving down and/or to the left represents smaller government. You could make the case that we should just look at spending to determine the size of government, but the policy debate suggests to me that diagonal arrows are more appropriate.

Now let’s use this tool to think about elements of the fiscal policy debate.

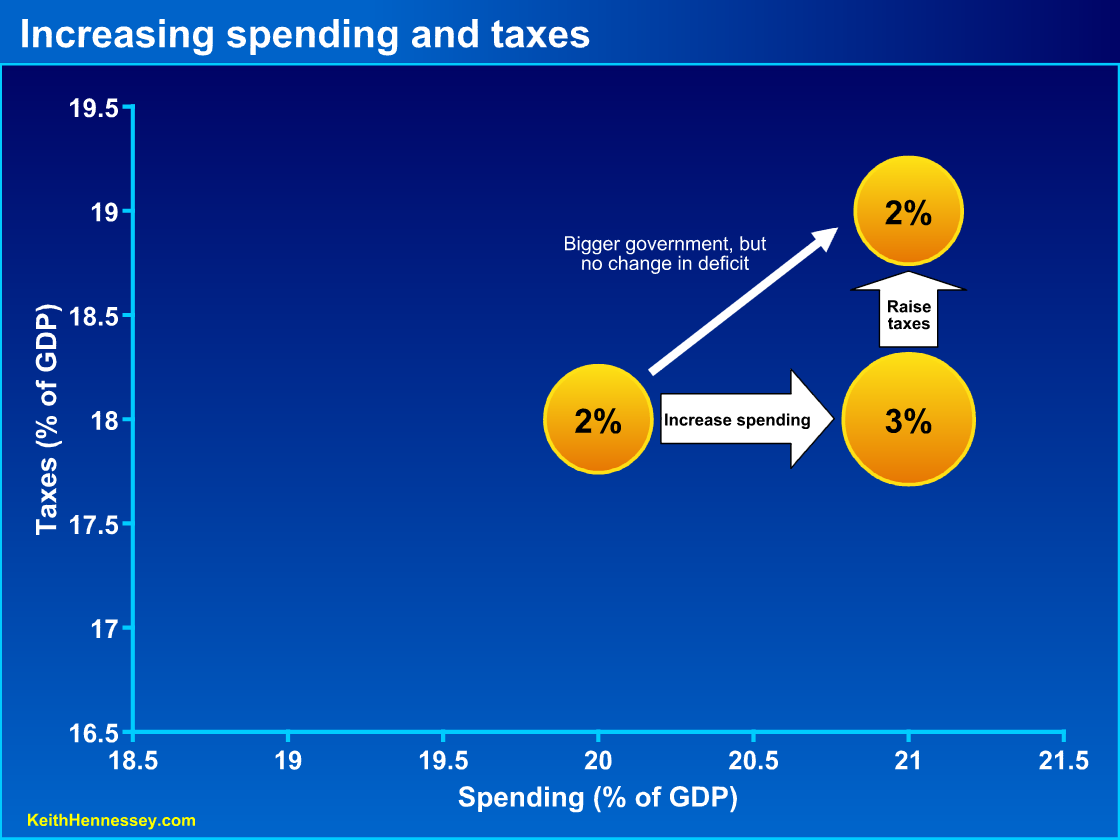

Our first strategic examples

Let’s use two graphs to look at the core philosophy driving the President’s and Congressional Democrats’ fiscal policy argument. While the details of PAYGO are a little funky because they apply only to some types of federal spending, these two graphs represent the underlying concept.

Under this logic, it’s OK to increase spending as long as you pay for it with higher taxes. If you move 1 percentage point (or any other amount) to the right by increasing spending, you have to raise taxes by an equal amount. The spending increase by itself would make the deficit bigger (2% to 3%), but the tax increase then reduces the deficit back to its original size. Government is bigger (higher spending and higher taxes), but the deficit has not increased.

In political rhetoric this is labeled (generally by opponents) as tax-and-spend. It’s probably better to think of it as spend-and-tax.

Here is where our budget bubble graph starts to get useful. Advocates for these policy changes argue that, since the deficit is unchanged, this policy change has had no major economic effect. “We have paid for our spending increase,” they argue, “our policy change does not increase the deficit.”

True. But this ignores that someone is paying higher taxes now. By moving up we are making someone pay more to the government. The right-then-up move illustrated above is a major fiscal policy change, and it is highly misleading to argue that it is insignificant because the deficit is unchanged. This is the primary purpose of Budget Bubble Graphs – to highlight major fiscal policy changes that are obscured by a one-dimensional focus on the size of the deficit.

Some advocates (on both sides of the partisan aisle) focus on the deficit with the intent of obscuring a significant change in the size of government. Many others in government and the press unwittingly ignore this component of major fiscal policy decisions.

In this example, the amount the government is borrowing from the private sector is unchanged, but the amount the government is taking from the private sector has increased. Whoever is paying these higher taxes has fewer resources to pay their family bills or expand their business. That is a significant consequence of this policy.

In addition, there is an economic efficiency loss from raising most kinds of taxes. Economists call this deadweight loss.

I have described what PAYGO allows in this case. It’s more accurate to think of PAYGO as a limitation. The intent of this part of PAYGO is not to move up on the graph. It is instead to prevent you from moving right without also moving up. If you want to spend more (move right), you have to

A dangerous side effect of this philosophy is concluding that if this PAYGO philosophy allows something, it is therefore fiscally acceptable or insignificant. I hope the above example demonstrates at a minimum that a big spending increase offset by an equally large tax increase is not insignificant. I also think it’s bad policy, but that’s a value judgment on my part.

Now that’s just one side of the pay-as-you-go philosophy. Here is the other side.

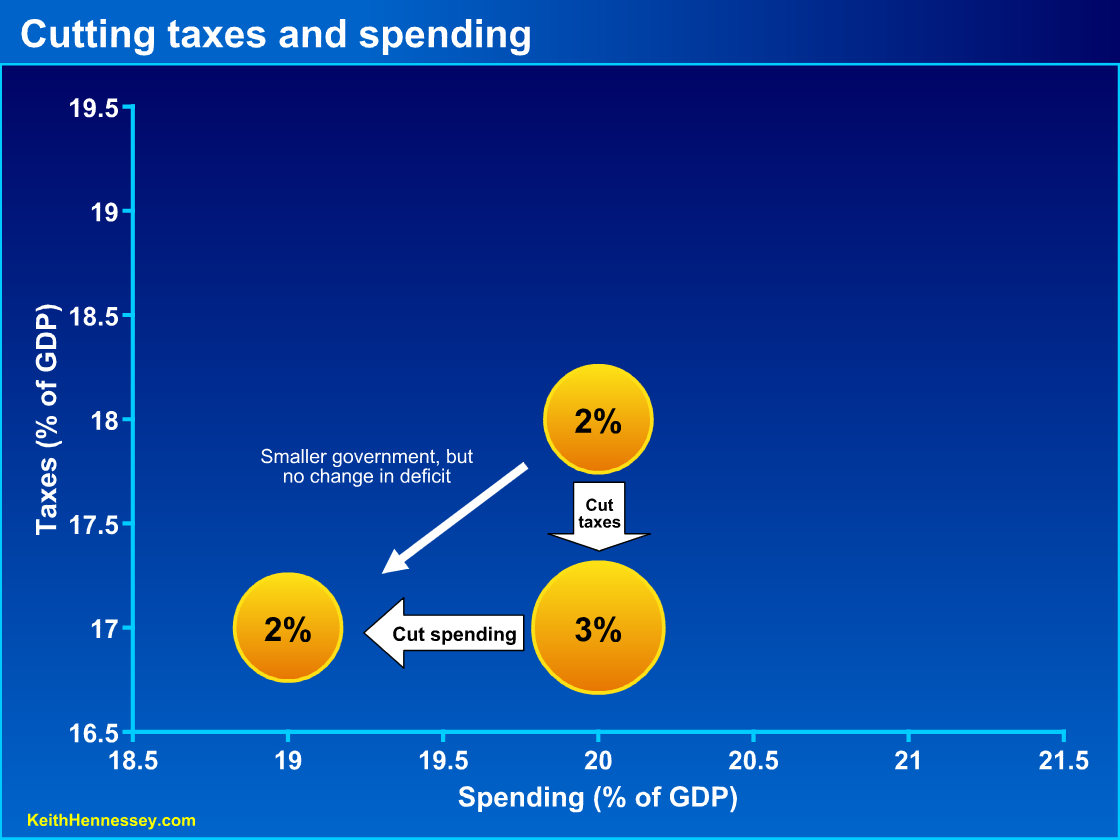

Under this set of PAYGO rules favored by the President and many of his Congressional allies, you can move down (cut taxes) only if you also move left (cut spending). It is again a limitation — you may not cut taxes (and thereby increase the deficit) unless you also [raise other taxes or] cut spending by at least an equal amount. Once again, the details allow only cuts in certain types of spending to count, but we can ignore that here.

In this graph policy makers cut taxes by 1% of GDP, increasing the budget deficit from 2% to 3%. They package this tax cut with spending cuts to keep the deficit at 2% of GDP. The deficit is unchanged from the starting point, but government is smaller as measured by either spending or taxes. Since the deficit is unchanged we have not increased future taxes. Since taxes are lower now, individuals, families, and firms have more resources today to use however they best see fit.

In future posts we can examine the Republican view of the PAYGO world and why it’s so hard to get a bipartisan agreement to reduce the budget deficit. Much of the partisan disagreement concerns proposals to move straight up or straight down on the graph, and we’ll look at that. We can also use Budget Bubble Graphs to analyze different examples of major legislation now being debated as well as for other interesting analysis.

My point today is simply to introduce you to this type of graph and to use it to demonstrate that we should care about both the deficit and the size of government. I have focused on the simplest examples to get you accustomed to using these graphs to help think about fiscal policy.

We have just scratched the surface of Budget Bubble Graphs. Stay tuned for more.