What is a budget resolution?

A budget resolution is an internal management tool used by Congress to structure its spending and tax decisions. It consists of legislative language and looks like a bill, but it’s not a bill. It is instead a concurrent resolution, which means that the House and Senate have to pass identical language, but it does not go to the President for his signature or veto.

The budget resolution is like a blueprint for a house. It’s not a house, it’s a plan for building one. A blueprint establishes the size of the house, the size of each room, and how the rooms are put together. A budget resolution does the same for federal spending and taxes. A budget resolution by itself does not spend any money or raise any taxes. It is instead the quantitative blueprint and rules for other legislation that does both of those things.

Each year on the first Monday in February the President proposes a budget. The main set of documents released from OMB are more than a thousand pages long. When you include the supplemental details provided by agencies, the full proposal is a multiple of that. But in the end it’s just a proposal and it has no legal binding authority. The Constitution gives the “power of the purse” to Congress, not to the President.

Congress can take the skeleton of the President’s proposal and use it to build their budget resolution or they can ignore it completely. They can write their own budget, as often happens when one or more houses of Congress are controlled by a different political party than the White House.

I think of a budget resolution as a top-down structure that basically consists of four parts:

- Totals – We intend the federal government to spend $X billion and collect $Y billion in taxes, resulting in a deficit of $(X-Y) billion.

- Committee allocations – We divide the $X billion of spending up among the various committees in Congress. This is done separately for the House and Senate committees, but they’re designed to match up.

- Processes – We can set up reconciliation processes to produce reconciliation bills, create points of order, and create reserve funds.

- Fluff – Non-binding “Sense of the Congress” statements.

As an example, last year’s budget resolution (I’m oversimplifying here):

- Said that for Fiscal Year 2010 the federal government should spend $3.36 trillion, collect $1.53 trillion in taxes, and therefore run a deficit of $1.83 trillion. It then sets similar parameters for each of the next four years, up through FY 2014. Budget resolutions typically cover either the next five or the next ten years at the discretion of Congressional leaders.

- Allocated that $3.36 trillion of spending to various committees in the House and Senate. In the Senate, the Finance Committee could spend no more than $1.23 trillion. The Appropriations Committee could spend no more than $1.81 trillion. The Armed Services Committee could spend no more than $136 B, and so on.

- Created a reconciliation process in the House and Senate. This process was later used to pass health care law #2 and was created for that purpose.

- Set up the pay-as-you-go rules that require entitlement spending increases and tax cuts to be offset so they are deficit neutral.

- Created 14 “reserve funds” in the House and 20 in the Senate. In theory, a deficit-neutral reserve fund smooths the procedural path for legislation that shuffles spending and taxes around for a particular purpose (like student loan reform or more veterans benefits) while not increasing the deficit. Other reserve funds are designed not to be deficit neutral, and allow Congress to increase spending or cut taxes, but subject to restraints: only by certain amounts that fit within the totals defined above, and only for particular purposes.

- Included Sense of the Congress provisions on homeland security, promoting innovation, pay parity, and Great Lakes restoration.

Once the House and Senate have agreed to the same budget resolution language, the numbers and rules within it bind Congress until a new budget resolution is adopted the following year. The power of the budget resolution comes from the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974, which sets up procedural rules that allow Members to enforce the budget resolution. I’m a bit more familiar with the Senate, so I’ll give an example there.

Suppose an agriculture bill is on the Senate floor and you want to amend that bill to increase mohair subsidies by $10 B per year. Such a spending increase would cause the spending in farm programs to exceed the amount allocated to the Agriculture Committee, so any of the other 99 Senators could raise a budget point of order that your amendment violates the Agriculture committee allocation in the budget resolution. You would need 60 votes to waive that point of order. If you couldn’t get 60 votes, then the point of order would be sustained and your amendment would die.

There’s a huge practical difference between getting 51 votes to pass an amendment, and getting 60 votes to “break the budget” and waive the point of order. Points of order like this are powerful tools to force legislation to conform to the numbers in the budget resolution. They force quantitative discipline on the legislative process. The discipline is imperfect and the budget is sometimes waived, but there is discipline nonetheless.

Without an annual budget resolution, that discipline does not exist. Committee chairman spend and tax as they see fit, because there is no overarching structure to reign them in. It can become budgetary chaos.

Because of this power, the budget resolution is one of the most important and most hotly contested legislative efforts of each year. While it looks like just lists of numbers and procedural rules, the budget resolution reflects enormous policy choices that shape the entire legislative landscape for the year. Budgeting is about choices and tradeoffs, and the budget resolution is where those choices are made. These hard choices often involve politically painful tradeoffs among important issues and powerful interests.

As an example, the budget resolution can establish whether cap-and-trade legislation must reduce the deficit (presumably by auctioning off permits) or can be deficit neutral, in which case carbon credits can be allocated to particular interests to help Members vote for the legislation. The budget resolution’s requirements on cap-and-trade can set a budgetary bar that could doom the legislation.

The enormous substantive impact also means that budget resolutions are typically partisan legislative efforts. The two parties are fairly far apart on major fiscal policy questions and the budget rules make compromise on a budget resolution less necessary than on traditional legislation, and so most budget resolutions pass the House and Senate on nearly party line votes.

Even within a political party it can be hard to bridge fiscal policy differences and a challenge for leaders to corral their members into a fiscal policy agreement.

In recent weeks House and Senate Democratic leaders have said they do not intend to try to pass a budget resolution this year. The statutory deadline for a budget resolution conference report is April 15th and is routinely missed, but it’s almost always complete by mid-May. Without a budget resolution there will be no discipline on tax or spending legislation other than the limited enforcement that can be derived from last year’s resolution. We can see one symptom of this as the Senate debates on an “extenders” bill that violates the majority’s own much-touted pay-as-you-go rules. Update: While the extenders bill appears to violate the Senate’s paygo rules, the majority works around this by designating as emergencies the provisions that are not offset. The bill therefore technically complies with the PAYGO rule. I think of it as violating the spirit of both the Senate’s PAYGO rule and the definition of an emergency.

Press reports suggest that in this heavily contested election year the Democratic Leaders don’t want to put their members through the tough votes that always happen during floor votes on the budget resolution, and they don’t want to force different parts of their Democratic caucus to fight with each other to reach agreement.

Since my policy experience began in 1995, there have been several instances where the House and Senate have failed to reach agreement on a conference report. This is, however, the first time Congress didn’t even try.

That’s an abdication of responsibility. Based on past experience, I expect I would oppose a hypothetical budget resolution compromise by the Democratic House and Senate majorities. Still, it would be better to have a budget resolution that I oppose than to have no structure and no formal budgetary discipline.

Voters elect Members of Congress to make hard choices.

Summary of Chairman Bernanke’s testimony

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke testified today before the House Budget Committee. Although his testimony is fairly succinct by itself, I have found that few people actually read Congressional testimony, so here is a summary. Where possible, I use the Chairman’s words. His comments on the budget (last section) are getting the most press attention.

The U.S. Economy

“Moreover, the economy–supported by stimulative monetary policy and the concerted efforts of policymakers to stabilize the financial system–appears to be on track to continue to expand through this year and next.”

- The Fed’s April forecast projected that GDP would grow around 3.5% this year, and “at a somewhat faster pace next year.”

- Economically and politically critical: “This pace of growth, were it to be realized, would probably be associated with only a slow reduction in the unemployment rate over time.”

- “In this environment, inflation is likely to remain subdued.”

He argues against a “double dip recession”:

Although the support to economic growth from fiscal policy is likely to diminish in the coming year, the incoming data suggest that gains in private final demand will sustain the recovery in economic activity. Real consumer spending has risen at an annual rate of nearly 3-1/2 percent so far this year, with particular strength in the highly cyclical category of durable goods. Consumer spending is likely to increase at a moderate pace going forward, supported by a gradual pickup in employment and income, greater consumer confidence, and some improvement in credit conditions.

He thinks business investment will likely be strong.

He identifies the ongoing overhang of excess housing supply as well as commercial buildings as a “significant restraint on the pace of recovery.” He also cites “pressures on state and local budgets, though tempered somewhat by ongoing federal support” as another restraint.

On the employment picture he emphasizes that it’s going to take a long time to close the employment gap:

Private payroll employment has risen an average of 140,000 per month for the past three months, and expectations of both businesses and households about hiring prospects have improved since the beginning of the year. In all likelihood, however, a significant amount of time will be required to restore the nearly 8-1/2 million jobs that were lost over 2008 and 2009.

He doesn’t sound too worried about inflation:

But aside from these volatile components, a moderation in inflation has been clear and broadly based over this period. To date, long-run inflation expectations have been stable …

Developments in Europe

“U.S. financial markets have been roiled in recent weeks by these developments

He endorses the European actions:

The actions taken by European leaders represent a firm commitment to resolve the prevailing stresses and restore market confidence and stability. If markets continue to stabilize, then the effects of the crisis on economic growth in the United States seem likely to be modest. Although the recent fall in equity prices and weaker economic prospects in Europe will leave some imprint on the U.S. economy, offsetting factors include declines in interest rates on Treasury bonds and home mortgages as well as lower prices for oil and some other globally traded commodities.

Fiscal Sustainability

In many ways, the United States enjoys a uniquely favored position. Our economy is large, diversified, and flexible; our financial markets are deep and liquid; and, as I have mentioned, in the midst of financial turmoil, global investors have viewed Treasury securities as a safe haven. Nevertheless, history makes clear that failure to achieve fiscal sustainability will, over time, sap the nation’s economic vitality, reduce our living standards, and greatly increase the risk of economic and financial instability.

On the short-term budget picture:

Our nation’s fiscal position has deteriorated appreciably since the onset of the financial crisis and the recession. The exceptional increase in the deficit has in large part reflected the effects of the weak economy on tax revenues and spending, along with the necessary policy actions taken to ease the recession and steady financial markets. As the economy and financial markets continue to recover, and as the actions taken to provide economic stimulus and promote financial stability are phased out, the budget deficit should narrow over the next few years.

I assume the Administration will see the Chairman’s “necessary policy actions taken to ease the recession and steady financial markets” language as an endorsement of the stimulus.

“Even after economic and financial conditions have returned to normal, however, in the absence of further policy actions, the federal budget appears to be on an unsustainable path.”

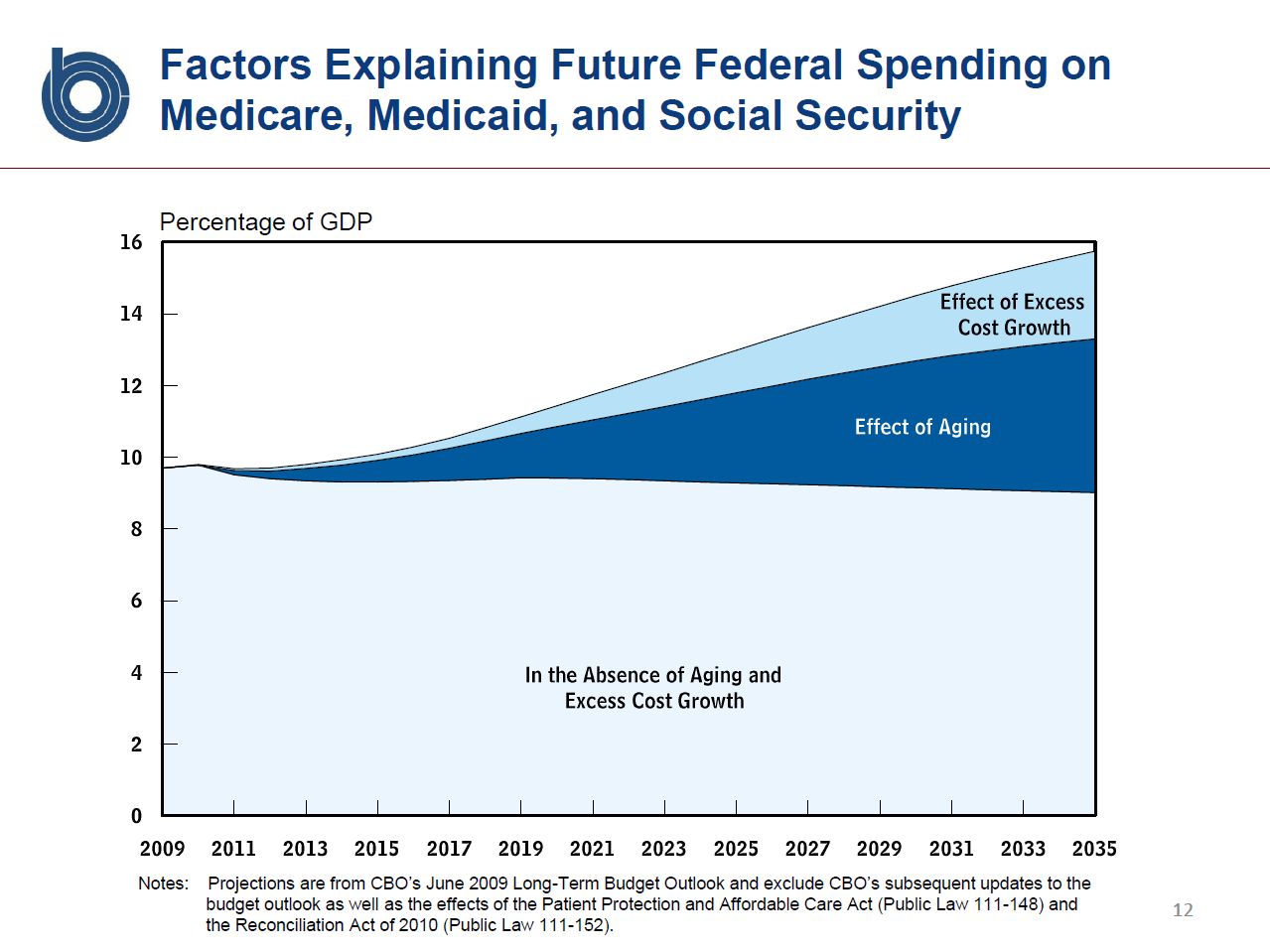

Finally, he gives the reasons (plural) for our long-term budget challenge:

Among the primary forces putting upward pressure on the deficit is the aging of the U.S. population, as the number of persons expected to be working and paying taxes into various programs is rising more slowly than the number of persons projected to receive benefits. Notably, this year about 5 individuals are between the ages of 20 and 64 for each person aged 65 or older. By the time most of the baby boomers have retired in 2030, this ratio is projected to have declined to around 3. In addition, government expenditures on health care for both retirees and non-retirees have continued to rise rapidly as increases in the costs of care have exceeded increases in incomes. To avoid sharp, disruptive shifts in spending programs and tax policies in the future, and to retain the confidence of the public and the markets, we should be planning now how we will meet these looming budgetary challenges.

Three cheers for the Chairman for identifying both demographics and growth in per capita health spending as drivers of our long-term budget challenges. If you listen to the Administration, you won’t hear about demographics, only health care costs.

(photo credit: official portrait on Wikipedia)

The new Democratic claim about job creation

A new claim about job creation appears to be bubbling up through the Democratic ranks. Here is the clearest statement of that claim, from Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) on Stuart Varney’s show:

On the pace that we’re on, with job creation in the last four months, if we continue on that pace, and all the leading economists say that it is likely that we will, we will have created more jobs in this year than in the entire Bush Presidency.

Ms. Wasserman Schultz is picking her timeframes carefully, in particular by ignoring the four million jobs lost during the first 11 months of a Presidency that is so far 16 months old.

Even today, after five straight months of job growth, three million fewer people are working than when President Obama took office. That’s hardly something to brag about.

And looking just at last month’s strong net increase of 431,000 jobs, we see that nine out of ten net new jobs were temporary government jobs for census takers. We all hope the pace of private job creation accelerates, but it’s too soon to declare this a strong and consistent employment recovery or to project its trend into the rest of the year.

Let’s look at how Ms. Wasserman Schultz justifies her claim.

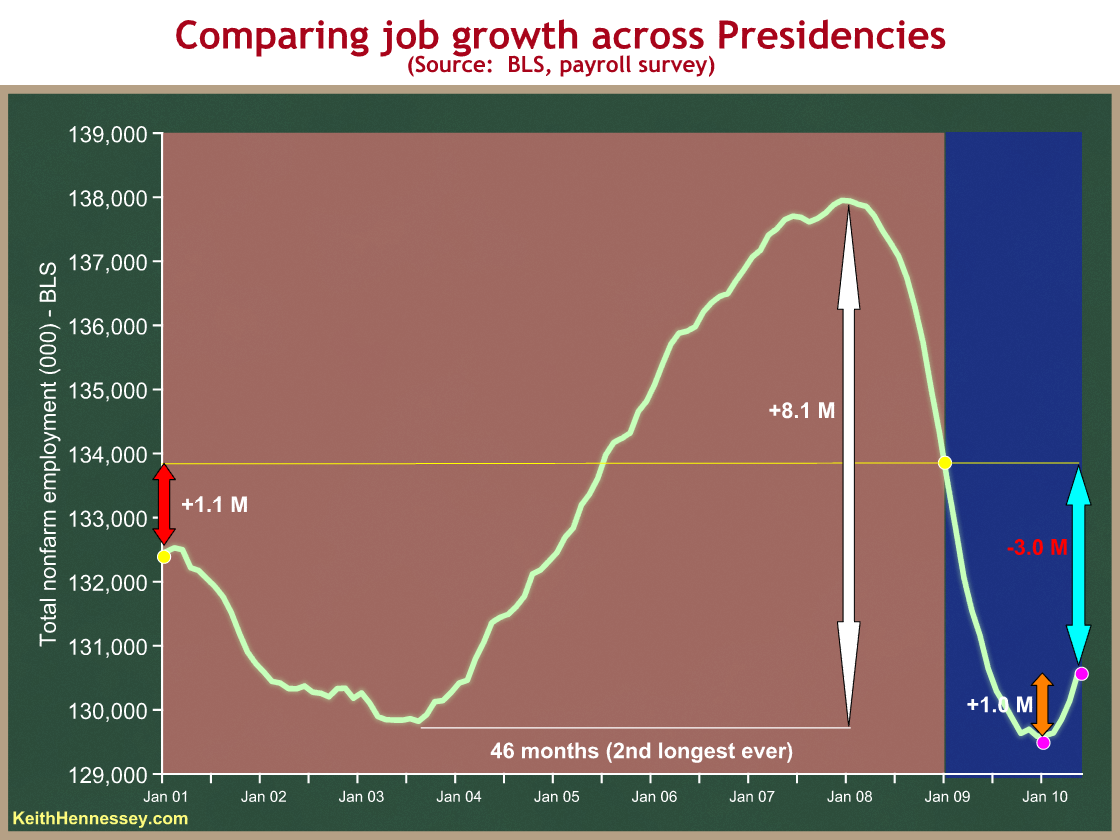

I have colored the Bush Presidency red and the Obama Presidency blue.

You can see two yellow dots in January 2001 and January 2009, and a thin yellow line extended so we can measure the difference between the two. The red arrows show that, if you measure only endpoint to endpoint, 1.1 million net net jobs were created during the Bush Administration (I’m using the payroll survey in all cases).

But this analysis misses most of the story. We can see a steady employment decline from early 2001 through mid-2003, followed by a steady, strong, and sustained period of job growth for almost four years. This 46 month period is the second longest in recorded history for sustained job creation in the U.S., and more than eight million jobs were created during this period (the white arrows). A mild recession began in late 2007, followed by a severe contraction in the second half of 2008 and continuing into the Obama Presidency.

Compounding the chicanery, Ms. Wasserman Schulz measures the Obama job creation beginning with the first pink dot in December 2009. Her conclusion is based on the orange arrows and her guess about how they will grow throughout this year. She’s ignoring the four million decline in employment from January 2009 (despite the stimulus), and she’s ignoring that we’re still three million jobs shy of where we were when President Obama took office. If she were to apply the same methodology to President Obama as she did to President Bush, she’d be comparing +1.1 M (Bush) with -3.0 M (Obama). But that wouldn’t look quite as good for her case.

Measuring employment either presidency by observing only the start and endpoints ignores a lot of important information and tells a misleading story. Comparing the entire Bush presidency with only the good news part of the Obama presidency is absurd.

Many economists prefer to compare economic statistics from one business cycle to the next – from peak to peak, or from trough to trough. Since business cycles don’t match political terms, this means that comparisons across presidencies are analytically difficult and often misleading. When an advocate like Ms. Wasserman Schultz compounds this by choosing her window to make her point, we’re at the mercy of her choice of timeframe, which is often chosen to justify a political argument.

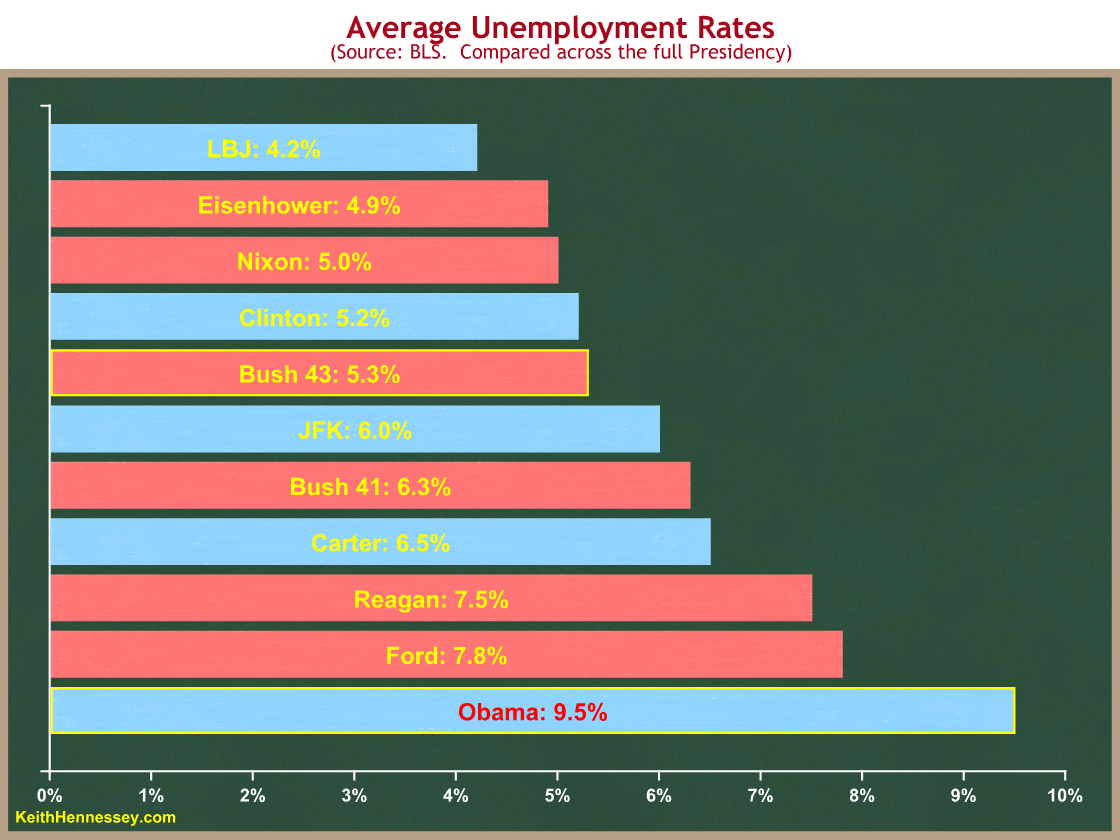

Since the policy and political debate force us to compare economies between elected terms, we need a better metric. The average unemployment rate is probably the best and fairest way to compare employment over time between Administrations. Since the labor force grows each year, comparing the number of jobs created in timeframes many years apart is misleading. The unemployment rate largely adjusts for these demographic trends because it is measured as a share of the labor force. And using the average unemployment rate over an entire Administration allows us to avoid endpoint biases and games and to more fairly compare Presidencies.

If Ms. Wasserman Schultz wants to use this better and fairer metric to compare the employment picture between the entire Bush presidency and the Obama presidency so far, I’m game:

President Obama’s 9.5% average unemployment rate is measured over a relatively short timeframe, and we all hope that average declines as the economy recovers and many more new jobs are created. Still, a fair comparison shows a strong 5.3% average unemployment rate for the Bush Presidency, and Obama partisans may want to wait for a lot stronger job growth before trying to compare the Obama employment record with that of President Bush.

Responding to the President’s Carnegie Mellon economic speech

Yesterday I tried to neutrally summarize the President’s 5,000+ words economic speech delivered last week at Carnegie Mellon University. Today I’ll give my views on the substance.

The new foundation is simply bigger government

Setting aside the tone, the President’s economic speech was simply an argument for bigger government. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that the President is for bigger government. I am a bit surprised that he’s willing to say it.

He frames the choice as one between Republican anarchy and his self-described reasonable middle ground balance of government and the private sector.

THE PRESIDENT: But to be fair, a good deal of the other party’s opposition to our agenda has also been rooted in their sincere and fundamental belief about the role of government. It’s a belief that government has little or no role to play in helping this nation meet our collective challenges. It’s an agenda that basically offers two answers to every problem we face: more tax breaks for the wealthy and fewer rules for corporations.

The last administration called this recycled idea “The Ownership Society.” But what it essentially means is that everyone is on their own. No matter how hard you work, if your paycheck isn’t enough to pay for college or health care or childcare, well, you’re on your own. If misfortune causes you to lose your job or your home, you’re on your own. And if you’re a Wall Street bank or an insurance company or an oil company, you pretty much get to play by your own rules, regardless of the consequences for everybody else.

The President sets up three straw men to make his case:

- Republicans want a Lord of the Flies-like anarchy.

- His critics claim the President wants socialism.

- We are coming out of a “lost decade” of failed economic policies that we must reject for the future.

The choice America faces, the President argues, is between no government and a reasonable balance.

The actual choice America faces is simply whether, compared to where we are now, we want bigger or smaller government. We are arguing about changes on the margin, not about a choice between anarchy and socialism.

As Greg Mankiw puts it, the relevant question is not whether you’re a libertarian, it’s whether you’re a libertarian at the margin. It’s not crazy, deceptive, or evil to believe there are significant roles for government in our society and our economy while at the same time arguing for less government than we have now, or while arguing against massive expansions of government.

The President also makes a silly argument. He takes specific examples of bigger government (like seat belts) and points out that at the time they were opposed by those who favored smaller government. He chooses as examples government policies which are overwhelmingly accepted in today’s society. He then implies that such flawed judgment must also apply to those who oppose his new favored expansions of government. I don’t think I need to walk through all the reasons why this logic is flawed.

I think the “lost decade” argument is also a straw man but will respond to it at another time.

The substance of the President’s new foundation

The President’s foundation is built on two core concepts:

Concept 1: The key to greater economic growth is more government spending on infrastructure, broadly defined to include education and job training.

Concept 2: Greater economic growth will result from the new health care laws, upcoming financial sector reforms, and as-yet undetermined policies that will result in “our government less burdened with debt.”

To demonstrate concept 1, here is a key quote from the speech, in which I will substitute “government spending on” for the President’s functionally equivalent words “investments in”:

It’s a foundation based on government spending on our people and their future; government spending on the skills and education we need to compete; government spending on a 21st century infrastructure for America, from high-speed railroads to high-speed Internet; government spending on research and technology, like clean energy, that can lead to new jobs and new exports and new industries.

The President is making the case for increased spending for a wide range of government programs. That’s a decades-old debate, and I’m not sure there’s much “new foundation” about it. I would instead prioritize slowing long-term entitlement spending growth, keeping taxes low, increasing global free trade and investment, and increasing flexibility in our labor markets and consumer-based decision-making in our health care markets. I would also prioritize K-12 education, but that is largely a state and local issue, and I surmise that insufficient funding is not the core weakness in our elementary educational system.

My relatively lower prioritization of public infrastructure does not mean I want to tear up the public highway system, or defund basic scientific research. Once again, the practical argument is about marginally more government spending on these priorities vs. marginally less, not whether they should be funded at all.

Concept 2 is a bit of a catch-all, supplemented by the laundry list in part III of the President’s speech. Team Obama has taken every economy-related policy proposed by the President and argued that it will result in greater economic growth. At best that’s an exaggeration.

I believe we need significant changes to our financial policy and structure, some of which will involve greater regulation and stricter supervision and oversight. Not yet knowing whether any government policies actually contributed to the Gulf spill, I would favor tighter safety regulation of deepwater drilling to drastically reduce the chance of this happening again.

These bigger government views on two specific areas can be consistent with a view that the health care laws moved in the wrong direction, and that our health care systems would be more efficient and effective with less government involvement. They can be consistent with opposing the House-passed cap-and-trade bill, and with a general reticence to embrace massive expansions of government regulatory power. They can be consistent with vigorous opposition to spending and taxes that are projected under the President’s budget to increase to historically unprecedented levels.

The choice described by the President does not exist. Excepting maybe Rep. Ron Paul, there are few true libertarians in public office. To my chagrin, many Republicans in Congress like many government spending programs as much as Democrats (think farm subsidies). The typical Washington spending fight is about whether real government spending on program X should increase 1 percent next year or 4 percent. In both cases government is growing. Anarchists don’t exist in American politics, and to claim that elected Republicans believe that “government has little or no role to play in helping this nation meet our collective challenges” is absurd.

The choice America faces is whether or not we want a wholesale expansion of government, and whether on the margin our society is improved by bigger or smaller government.

In targeted cases like oil drilling safety and certain financial sector problems, I’m for slightly bigger government. In almost all other cases, I believe we’d be better off as a society leaving many more resources and decisions in the hands of private citizens. This is exacerbated by being on a path of unsustainable future spending growth. I think it’s particularly irresponsible to suggest a greater role for government when we don’t know how to meet outstanding promises already made for the future.

The President says his new foundation will support a more rapidly growing economy. All I see it supporting is a bigger government.

(photo credit: White House video)

Cliff Notes: The President’s Carnegie Mellon economic speech

Last Wednesday the President spoke about the economy at Carnegie Mellon University. Administration officials billed this as a major economic address, the follow-up to his speech last April at Georgetown. I think the most accurate and fairest way to understand the views of an elected official begins with what he or she says. The problem is that this speech is more than 5,000 words, so almost no one will read the whole thing.

In summarizing it I still ended up at around 1,300 words. Think of it as getting 75% savings.

I will respond to the speech soon. For now, this is my attempt at a non-judgmental summary. Where you don’t see quotation marks I am paraphrasing him, fairly I hope.

The speech naturally breaks into three parts:

- Part I: The Choice

- Part II: The Foundation

- Part III: The Laundry List

There are some obvious topical subdivisions which I have labeled.

Part I: The Choice

The oil spill is my top priority.

The macroeconomy

I inherited an extremely weak economy, “one of the worst economic storms in our history.”

I took bold and unpopular actions, and they worked. “These steps have succeeded in breaking the freefall.”

“We’re again moving in the right direction.”

“This economy is getting stronger by the day.”

[But] “It’s not going to be a real recovery until people can feel it in their own lives.”“In the immediate future, this means doing whatever is necessary to keep the recovery going and to spur job growth.”

Why we need a new foundation

The last ten years were terrible economically for American families. “Some people have called the last 10 years ‘the lost decade.'”

There has been “a sense that the American Dream might slowly be slipping away.”

China and India and Europe are “building high-speed railroads and expanding broadband access.” They’re making serious investments in technology and clean energy because they want to win the competition for these jobs.

We can’t afford to return to the pre-crisis status quo. We can’t go back to an economy that was too dependent on bubbles and debt and financial speculation.”

“We have to build a new and stronger foundation for growth and prosperity … and that’s exactly what we’ve been doing for the last 16 months.

It’s a foundation based on investments in our people and their future; investments in the skills and education we need to compete; investments in a 21st century infrastructure for America, from high-speed railroads to high-speed Internet; investments in research and technology, like clean energy, that can lead to new jobs and new exports and new industries.

This new foundation is also based on reforms that will make our economy stronger and our businesses more competitive — reforms that will make health care cheaper, our financial system more secure, and our government less burdened with debt.”

International & Trade

“We have to keep working with the nations of the G20 to pursue more balanced growth.”

“We need to coordinate financial reform … so that we avoid a global race to the bottom.”

“We need to open new markets and meet the goal of my National Export Initiative: to double our exports over the next five years.”

“We need to ensure that our competitors play fair and our agreements are enforced.”

Republicans are partisan and for no government

Republicans keep saying no to everything we’re doing.

“And some of this, of course, is just politics.”

“But to be fair, a good deal of the other party’s opposition to our agenda has also been rooted in their sincere and fundamental belief about the role of government. It’s a belief that government has little or no role to play in helping this nation meet our collective challenges. It’s an agenda that basically offers two answers to every problem we face: more tax breaks for the wealthy and fewer rules for corporations.”

“The last administration called this recycled idea ‘The Ownership Society.’ But what it essentially means is that everyone is on their own. No matter how hard you work, if your paycheck isn’t enough to pay for college or health care or childcare, well, you’re on your own. If misfortune causes you to lose your job or your home, you’re on your own. And if you’re a Wall Street bank or an insurance company or an oil company, you pretty much get to play by your own rules, regardless of the consequences for everybody else.”

My philosophy of government is a middle ground, rejecting too much government

“Government cannot and should not replace businesses as the true engine of growth and job creation.”

“Too much government can deprive us of choice and burden us with debt.”

“But I also understand that throughout our nation’s history, we have balanced the threat of overreaching government against the dangers of an unfettered market.”

“[O]ne-third of the Recovery Act we designed was made up of tax cuts…”

“[D]espite calls for a single-payer, government-run health care plan, we passed reform that maintains our system of private health insurance.”

The choice

Republicans/Conservatives/Big Business have argued against many good things done by government: Social Security, Medicare, deposit insurance, seat belts, clean air and water.

“And all of these claims proved false. All of these reforms led to greater security and greater prosperity for our people and our economy. And what was true then is true today.”

“For much of the last 10 years we’ve tried it their way.”

“And now we have a choice as a nation. We can return to the failed economic policies of the past, or we can keep building a stronger future. We can go backward, or we can keep moving forward.”

Part II: The New Foundation

“The first step … has been to address the costs and risks that have made our economy less competitive — [1] outdated regulations, [2] crushing health care costs, and [3] a growing debt.”

Financial reform is good and “sweeping”

It “will help prevent another AIG”

“It will end taxpayer-funded bank bailouts.”

“It contains the strongest consumer protections in history.”

Health care reform

We did health care reform because “we can’t compete in a global economy if our citizens are forced to spend more and more of their income on medical bills; if our businesses are forced to choose between health care and hiring; if state and federal budgets are weighed down with skyrocketing health care costs.”

“The costs of health care are not going to come down overnight just because legislation passed, and in an ever-changing industry like health care, we’re going to continuously need to apply more cost-cutting measures as the years go by.”

Health care reform did good things.

“The other party has staked their claim this November on repealing these health insurance reforms instead of making them work. They want to go back. We need to move forward.”

Deficits and debt

Thanks to the Bush tax cuts and prescription drug benefit, I inherited a $1 trillion one-year deficit and projected deficits of $8 trillion over the next decade.

I inherited a severe recession “and the effects of the recession put a $3 trillion hole in our budget before I even walked through the door.” Additionally, the steps that we had to take to save the economy from depression temporarily added more to the deficit … about $1 trillion. Of course, if we had spiraled into a depression, our deficits and debt levels would be much worse.

“Now, the economy is still fragile, so we can’t put on the brakes too quickly. We have to do what it takes to ensure a strong recovery.”

We need to extend unemployment insurance.

We need to give more money to state and local governments so they don’t have to fire teachers.

“There are four key components to putting our budget on a sustainable path. Maintaining economic growth is number one. Health care reform is number two. The third component is the belt-tightening steps I’ve already outlined to reduce our deficit by $1 trillion. … The fourth component is [the Fiscal Commission.]”

Part III: The Laundry List

Education reform

- Race to the Top

- Replace guaranteed student loans with direct loans

- “Revitalize our community colleges”

Infrastructure

- High-speed rail

- High-speed broadband

- Clean energy subsidies

Energy

- “I supported a careful plan of offshore oil production as one part of our overall energy strategy. … But … only if it’s safe, and only if it’s used as a short-term solution while we transition to a clean energy economy.”

- “It means tapping into our natural gas reserves, and moving ahead with our play to expand our nation’s fleet of nuclear power plants.”

- We need to “put a price on carbon pollution.”

- We will get “a comprehensive energy and climate bill” done.

Research and innovation

- Make the research and experimentation tax credit permanent.

“The role of government has never been to plan every detail or dictate every outcome. At its best, government has simply knocked away barriers to opportunity and laid the foundation for a better future. Our people — with all their drive and ingenuity — always end up building the rest. And if we can do that again — if we can continue building that foundation and making those hard decisions on behalf of the next generation — I have no doubt that we will leave our children the America that we all hope for.”

(photo credit: Obama Visits Carnegie Mellon IX. by Patrick Gage)

CBO Director Elmendorf destroys a core Presidential health care argument

CBO Director Dr. Douglas Elmendorf has posted the slides he used in a presentation Wednesday to the Institute of Medicine, titled Health Costs and the Federal Budget. The presentation obliterates the claims of the President and his allies about the effects of the new laws on federal health spending and the budget.

For months the President and his Budget Director correctly argued that the goal of health care reform was to “bend the cost curve down.” The projected path of per capita health spending is unsustainable and will result in three bad outcomes:

- those with health insurance will have less money available for other needs;

- it will be harder for the uninsured to buy insurance; and

- government spending on Medicare and Medicaid will break federal and state budgets.

Here is the President at the Blair House:

The third thing it seems — I assume we can all agree on is that over the last decade costs have doubled for health care in America — costs have doubled for government-provided health care, but everybody’s health care. And that that meant that right now everybody knows that that wrecks budgets, it wrecks state budget, it wrecks family budgets, it wrecks federal budgets. Every 35 cents of every dollar spent on health care is spent by the federal government or the state governments for Medicare and Medicaid — 35 cents on the dollar. That doesn’t count veterans and other things, just those two. And so — and what’s happened is — on the dollar, on every health care dollar.

And so we’re facing, all of us around this table, Democrat and Republicans, are facing the fact that there’s $919 billion now we’re spending on Medicare and the federal portion of Medicaid, and that if things — I don’t see any firewall is going to keep costs from doubling again, we’re going to be talking about in the year 2019 we’re going to be spending $1.7 trillion if we don’t do something to bend that curve.

A common refrain from the President and his Budget Director was “health care reform is entitlement reform.” And through two budget cycles, when senior Administration officials were pressed on their plans for deficit reduction, they always returned to the argument that health care reform would substantially improve the federal budget outlook.

CBO Director Dr. Douglas Elmendorf has shown this argument to be incorrect.

This is the best and most direct presentation I have seen on the subject. I commend Dr. Elmendorf for his honesty, clarity and bluntness. I wish he had been this blunt and this clear in February and March before these bills became law.

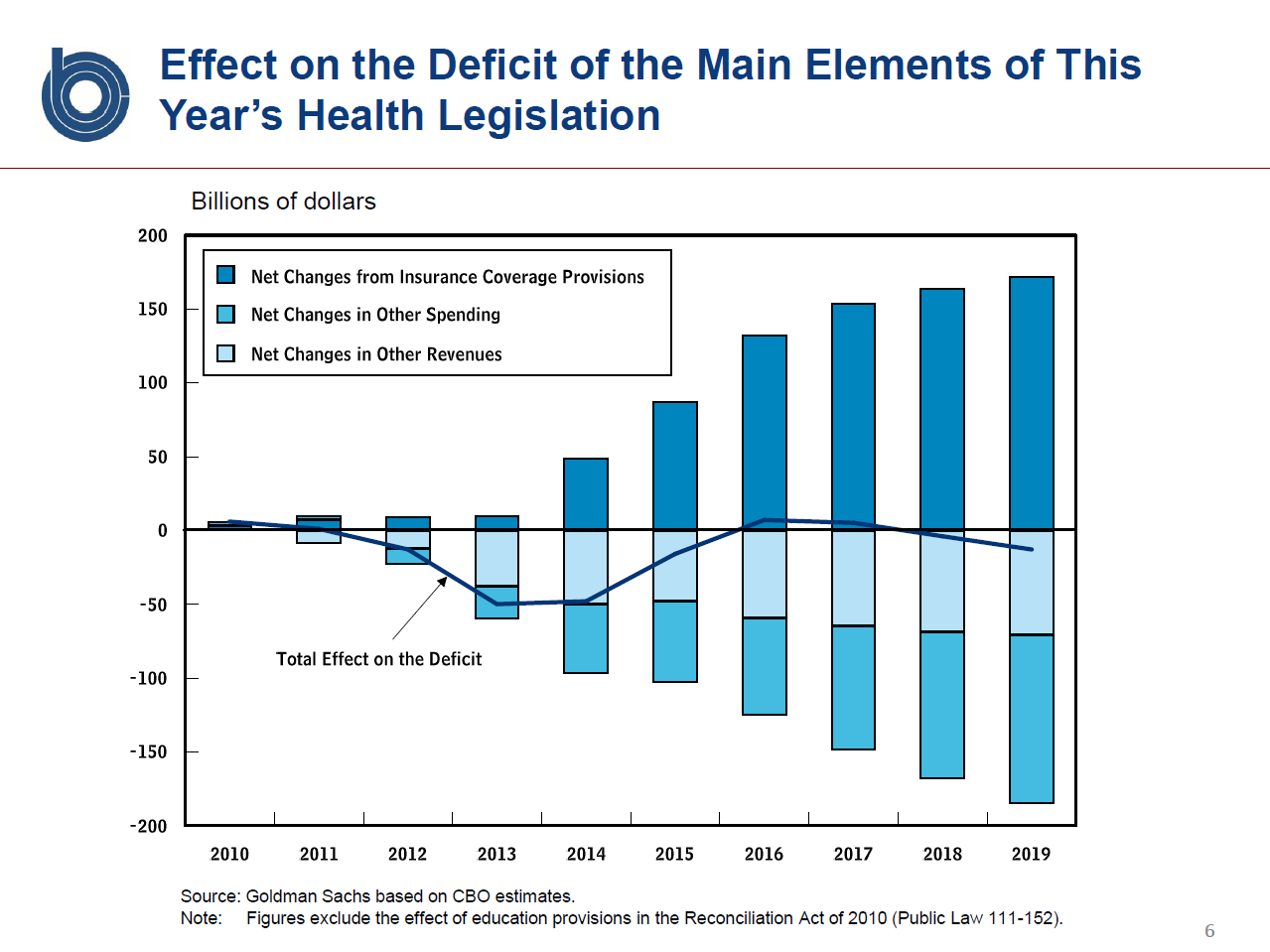

Here is Dr. Elmendorf’s first slide. Emphasis is mine.

The Challenge

Rising health costs will put tremendous pressure on the federal budget during the next few decades and beyond. In CBO’s judgment, the health legislation enacted earlier this year does not substantially diminish that pressure.

Here he shows the effects on Medicare spending of the two new health care laws, as well as the effect if Congress permanently extends a Medicare “doctors’ fix” like the “temporary” one being considered in the House today. The light blue line represents Medicare spending before the new laws, the dark blue line after the new laws, and the dotted line is the new laws plus a permanent doc fix. You can see that there is net Medicare savings even with a permanent doc fix, but the unsustainable spending growth still exists. And this is the part of the federal government where they “cut” (slowed the growth of) spending to pay for part of the new health care subsidies.

<

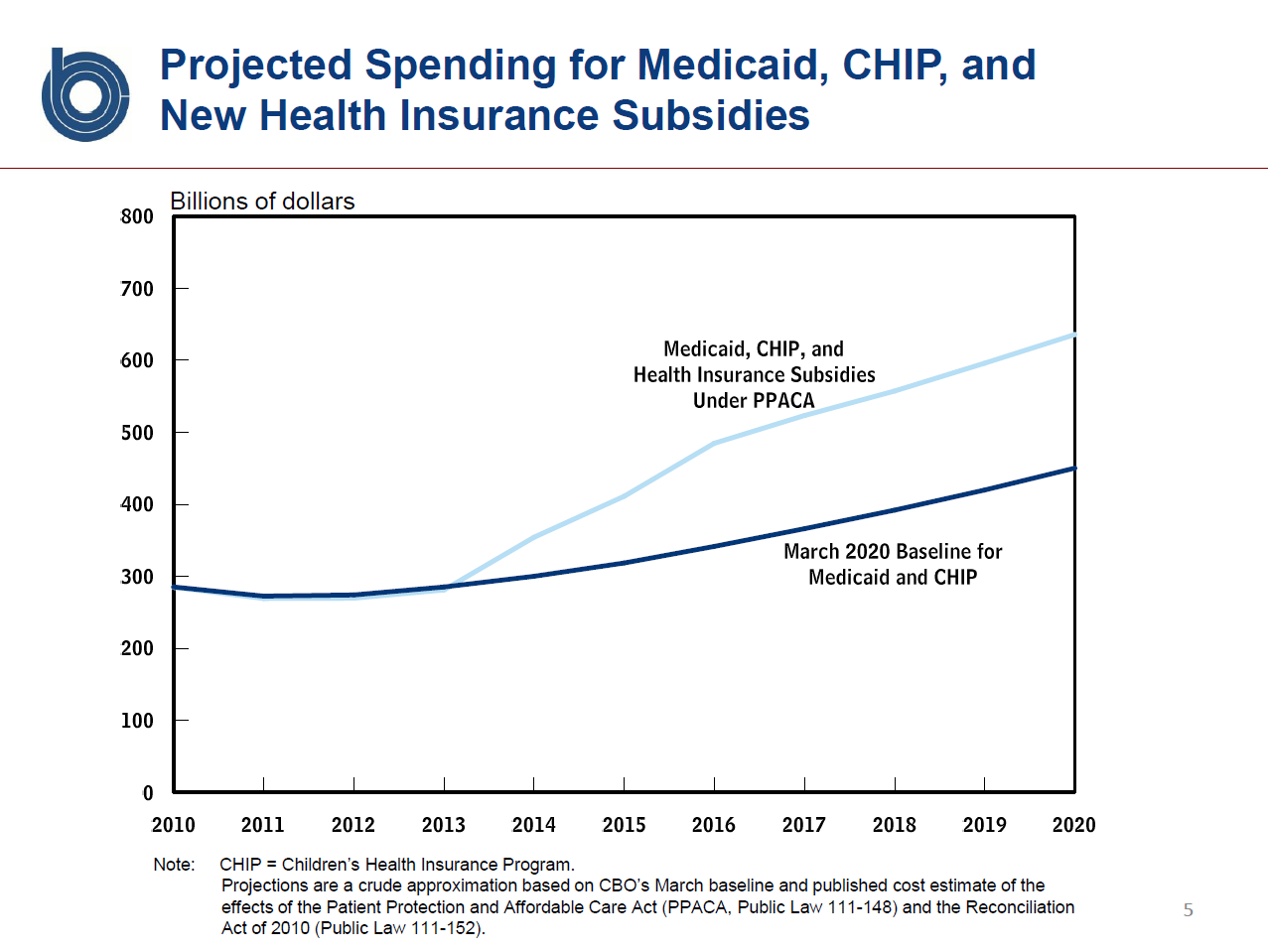

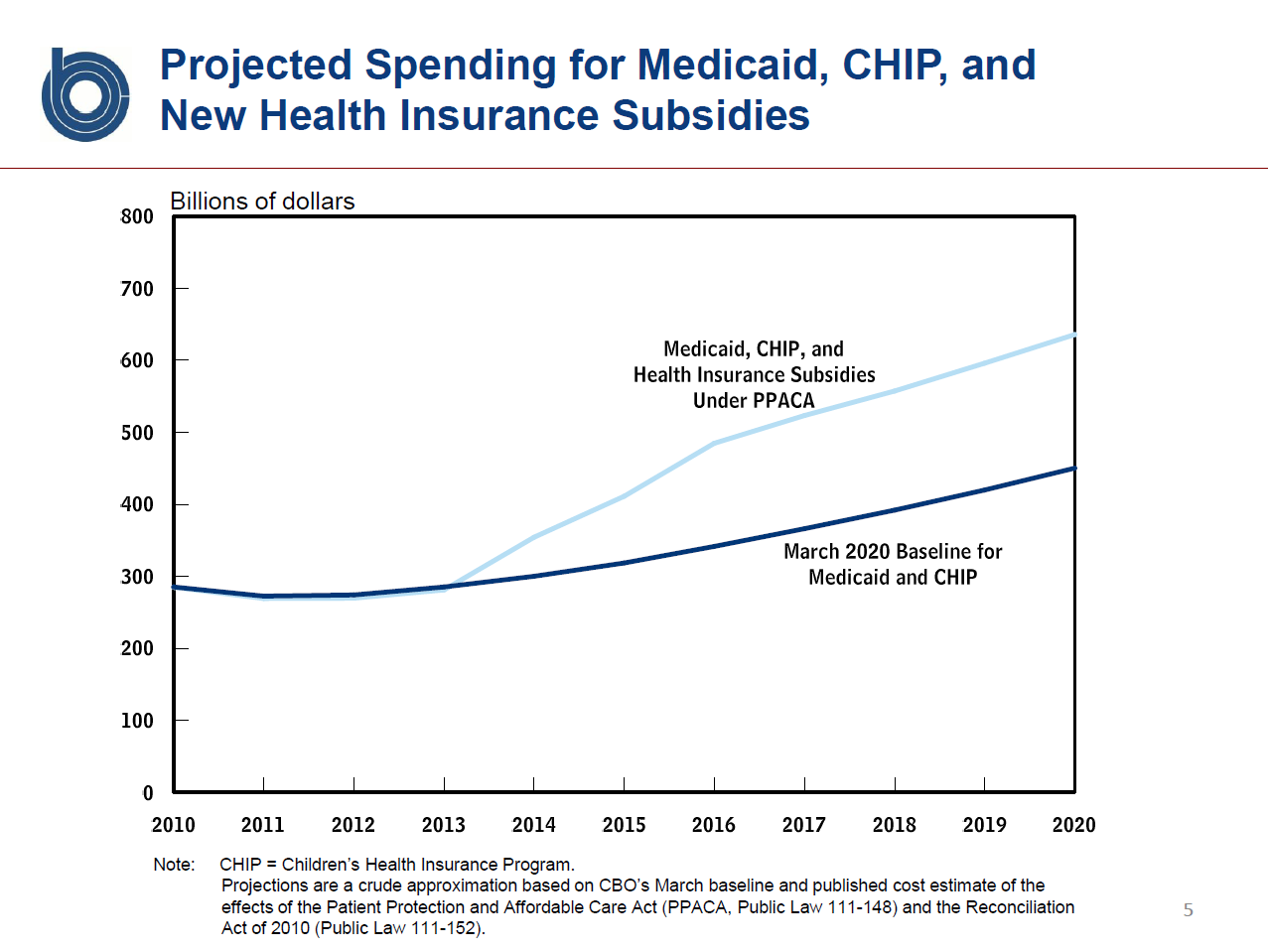

Now Dr. Elmendorf shows us the effects of the new laws on spending for Medicaid, CHIP, and the new health insurance subsidies’ You can see how the new spending line (in light blue) is an enormous increase over the baseline spending in dark blue.

OK, now let’s examine the net effects of the two laws.

Since the dark blue bars are roughly the same height as the combination of the light blue bars, the net deficit effect shown by the line is right about zero. Congressional Democratic leaders optimized to maximize coverage and minimize political pain from spending cuts and tax increases without increasing the deficit. Had they instead focused on the the President’s stated priority of “bending the cost curve down,” this graph would have looked quite different. The deficit reduction boasted about by the Administration and its allies is trivially small.

Dr. Elmendorf is direct:

<

blockquote>

The legislation will increase

The legislation will reduce budget deficits by about $140 billion during the 2010-2019 period and by an amount in a broad range around one-half percent of GDP during the following decade.

Q: How can both these statements be true? Over the next decade, how can the new laws increase the federal budgetary commitment to health care while reducing the deficit?

A: By redirecting non-health dollars to health. The increased Medicare payroll taxes on “the rich” are the best example. These laws devote more federal resources to health care. We were supposed to move the other way and devote less.

On February 23, 2009, the President said:

In the coming years, we’ll be forced to make more tough choices and do much more to address our long-term challenges, from the rising cost of health care that Peter described, which is the single most pressing fiscal challenge we face by far, to the long-term solvency of Social Security.

Once again Dr. Elmendorf debunks this claim that “it’s all about health cost growth.” This graph shows that, at least for the next decade, most of the growth in federal entitlement spending is the result of aging. Excess cost growth of health spending is a critically important but secondary factor.

Finally, here is Dr. Elmendorf’s concluding slide. Emphasis again is mine.

Putting the federal budget on a sustainable path would almost certainly require a significant reduction in the growth of federal health spending relative to current law (including this year’s health legislation).

Never before have I seen a CBO Director so bluntly refute the policy claims of a President and his Budget Director.

A $50 B fig leaf

House Democrats have modified their “extenders” bill and appear to be bringing it to the floor for a vote today. Monday’s version would have increased the deficit by $134 B over the next decade. Today’s version would increase the deficit by $84 B over that same timeframe. What hard choices did the Leaders make to cut the net deficit impact by $50 B?

None.

They simply extended the most expensive provisions for a shorter period of time:

- The new bill extends the unemployment insurance and COBRA health insurance benefits through November 2010 rather than through December 2010 in Monday’s version.

- The Medicare “doctors’ fix” would extend through 2011, rather than through 2013 in Tuesday’s version. (Note: In Monday’s post I mistakenly wrote that the bill contained an 18-month doctors’ fix.)

CBO has to score the amendment as written, so these two provisions are scored as “saving” $50 B relative to the Monday version. But just as it was unreasonable to assume that the increased Medicare spending for doctors would suddenly stop at the end of 2013, it is similarly foolhardy to assume it will stop at the end of 2011.

They are doing in this bill exactly what they did in the two health care bills in March: shifting some of the spending into future legislation to reduce the apparent cost of the current bill.

Will it work again? Will Blue Dogs and other House Democrats who opposed Monday’s version vote for today’s version thanks to this $50 B fig leaf?

(photo credit: Fig Leaf by geishaboy500)

Proud to underfund employee pensions?

The “tax extenders” bill, which yesterday I relabeled The Hypocrisy Act of 2010, contains some little-discussed provisions that would allow certain firms to further underfund their employee pensions. Advocates for the legislation promote this as a virtue, continuing a longstanding bipartisan trend of Congress rewarding bad pension behavior by both management and labor bosses in firms with a certain type of pension plan. These provisions are irresponsible and should be removed from the bill.

I’m going to use this as an opportunity to provide a crash course in a few aspects of pension policy. Let’s begin with some background on defined contribution and defined benefit pension plans.

In a defined contribution (DC) pension plan, an employer commits to contributing specific dollar amounts into an employee’s pension account. The employee then makes investment decisions for the funds in his account. The employee has both the upside and downside investment risk: if he invests well, he will have more for retirement. If he invests poorly, he will have less. The employer usually contracts out to a private investment firm (like Fidelity) for the account and investment management.

In a defined benefit (DB) pension plan, an employer commits to pay the employee a specific benefit amount at retirement. The employer owns both the upside and downside investment risk.

If a worker is risk averse toward investment, then the advantage goes to the DB plan. If he thinks he can manage his investments better than his employer can, then the advantage goes to the DC plan. Many workers are risk averse with their retirement planning. Also, if you hate private investment firms (as some on the left do), then you probably don’t like that aspect of a DC plan.

In a defined contribution plan, the employer deposits funds regularly (often with each paycheck) into each employee’s account. While the final pension benefit at retirement is uncertain because of investment risk, the current existence of the employer’s contributions is not. We say this account is fully funded or that the future benefit, while uncertain in amount because of investment risk, is prefunded. The employee is often required to match a portion of the employer’s regular contributions.

In a defined benefit plan, the employer contributes a lump sum regularly to the pension plan in the aggregate. The contribution amount is at the discretion of the employer, but the law establishes rules that determine a minimum contribution. In theory, a well-designed law should require the employer to regularly contribute enough cash to keep all the pension promises made by the employer fully prefunded. That way, if the employer goes bankrupt, there are enough funds already set aside to pay all the retirement promises previously made. There is a significant opportunity cost for firm management to making pension plan contributions: every dollar contributed to the pension plan is a dollar that cannot be used to pay current wages and benefits, or invest in new capital, or pay dividends to firm owners.

But the calculation of “How much does firm management need to contribute to its DB plan to keep it fully funded?” depends on the key discount rate used to calculate the future cost of those pension promises. If this discount rate is low, then the present value of future pension promises will be high, and the present value of pension plan assets (assuming certain investment returns) may be insufficient to cover those promises. The plan will be underfunded. If the discount rate for liabilities is high, then the plan will be fully funded and the employer could appear to responsibly offer employees new pension promises, thinking that enough money has been set aside to pay past promises.

The discount rates that employers must use are defined by law. Employers and labor leaders lobby Congress to set an artificially high discount rate, so that the pension plan looks healthy and the firm management doesn’t have to contribute as much cash each quarter to the DB pension plan. This allows management to chronically underfund the pension plan while honestly stating that they are complying with pension law. And it allows labor bosses to prioritize in their negotiations with management current wages and benefits over funding past pension promises.

Since DC plans are by design always fully funded and DB plans often are not, the advantage here goes to DC plans. The employees and retirees in DB plans often don’t know this, however, because their funds are comingled and therefore obscured, and because the accounting rules are deceptive, the result of lobbying by management and labor. This strategy collapses if the firm goes bankrupt and the underfunding becomes real.

In a defined contribution plan, the employee legally owns the funds in his account. In a defined benefit plan, he owns a (legally binding) promise from his employer that the funds will be there when the employee retires. This has two effects:

- A DC plan is portable, a traditional DB plan is not. If the worker changes jobs, he can take his DC account balance with him.

- If the employer goes bankrupt:

- The worker with the DC plan sees no effect on the pension he has earned so far, since he legally owns the funds in his account.

- The worker with the DB plan sees his employer “dump” the pension plan onto the government-run defined benefit plan insurance company, called PBGC: the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

- PBGC takes all the assets in the pension plan, and all the pension promises made up to that point.

- PBGC then pays all the previously-earned pension promises, up to a ceiling (which in 2010 is $54,000 per year for someone retiring at 65).

- If there aren’t enough assets in the plan to pay the promises up to the ceiling, then PBGC makes up the difference.

- If there are enough assets to pay up to the ceiling, but not all the promises above the ceiling, then retirees with pension promises above the ceiling get a “haircut” (proportional reduction) in their pension benefit. They lose part of their pension because their employer underfunded the promise and went bankrupt.

The legal ownership, portability, and elimination of bankruptcy risk are advantages of DC plans over DB plans.

The PBGC is funded by insurance premiums, charged to firms with DB pension plans. Those premiums are again determined by law, again subject to lobbying, and are therefore in many cases lower than an actuarially fair premium. When a firm dumps its plan on PBGC, other firms with DB plans are hurt since their premiums are more likely to increase. In the extreme, experts fear that at some point PBGC will run out of money and come to Congress for a taxpayer bailout. As we all now know, that kind of risk should not be ignored.

The further problem is that most firms that offer DB pension plans are in industries with a high risk of bankruptcy. Several large steel manufacturers dumped their DB plans on the PBGC years ago, and airlines often flirt with it. Workers and retirees shafted by bankruptcy is therefore a real risk. Low wage and short-time employees are generally protected by PBGC’s insurance, but those who have worked long enough or had high enough wages to earn pension benefits above the PBGC ceiling lose out.

This is a textbook case of moral hazard. The presence of government insurance with artificially low premiums encourages firm managers and labor union bosses to cooperate and shift some of the costs of future employee pensions onto the PBGC and maybe onto taxpayers. Management and labor agree to pay employees higher wages and benefits now, to increase the promised future retirement benefit promises from that plan, but to underfund those promises. They are, in effect, gambling workers’ pensions on the firm’s ability to avoid bankruptcy.

Defined Benefit Pension Reform

President Bush and his team pushed for defined benefit pension reform, based on five principles:

- Keep your promises, in advance: If an employer makes a pension promise, he or she should fully prefund that promise.

- Don’t disguise your underfunding: Plans should be required to accurately measure their pension plans using a conservative discount rate for liabilities (like Treasuries or a AAA corporate bond rate).

- Don’t hide your underfunding: That information should be transparent to current employees, retirees, investors, and everyone else. Don’t hide your underfunding.

- Get to full funding ASAP: Firms that have underfunded DB pension plans should be required to, over time, bring those plans up to full funding.

- We’ll negotiate on a reasonable definition of ASAP: A reasonable transition time for (4) can be negotiated, balancing firms’ current needs for revenues with a policy desire to get to full funding as quickly as possible.

Unlike many economic policy issues, DB pension reform involves a three-sided interest battle, among management, labor leaders, and workers+retirees. The problem is that management and labor leaders team up as described above to protect their own interests, jeopardizing the interests of workers+retirees. (An economist would say that labor leaders have an “agency problem” here, where their interests differ from those of the workers they claim to represent.) Novice policy observers get confused because they’re used to Republicans siding with management and Democrats siding with labor. They see bipartisan agreement with just a few outliers (from both parties) who are complaining loudly about some nebulous risk of future harm to workers and retirees. This is an example of where interest-group driven bipartisanship drives irresponsible policy.

A few members of Congress withstood the pressure from management and labor and pushed policies along the lines of President Bush’s. Notable for their admirable and responsible behavior were Rep. John Boehner and Senators Grassley and Baucus. Their leadership led to President Bush signing a DB pension reform law in 2006.

This law made progress on the above goals but was far from perfect. At the time, we looked on it as an incremental improvement over current law. In particular, we thought it phased up to full funding far too slowly.

One medium-sized policy victory in that law was a restriction that firms with severely underfunded DB plans could not make any new pension promises until they had fully funded their previous promises. While I hope this seems inherently reasonable and responsible to you, we met with (and overcame) fierce resistance to it at during the legislative process.

Hypocritical pension funding “relief”

The new House version of the extenders bill would undo much of that good work by providing “temporary pension funding relief” to firms offering DB pension plans.

The argument seems reasonable on its face: We’re in the early stage of an economic recovery, and our firm needs to use all its available resources to survive and eventually grow and hire more workers. The government should therefore relax the onerous requirements that management contribute large amounts of cash now to the firm’s DB pension plan.

But there is always an excuse not to contribute to your employees’ pension plan. When times are tough, the firm needs those resources to grow or even to survive. When times are good, the markets are doing well, the assets in the pension plan look healthy, and the firm managers argue they don’t need to contribute to the plan. The plans remain chronically underfunded, and retiree pensions are at perennial risk of firm bankruptcy.

I won’t go into the details of each of the four provisions affecting “single employer” DB plans, or the others affecting “multi-employer” DB plans. While the forms of the changes are different, each has a similar result: firms would be required to contribute less to their employees’ pension plans over the next year or two.

One particularly egregious provision (in section 303 of the draft House bill) would begin to weaken the “no new promises until you fully fund old promises” rule. Even worse, it would do so through an accounting change to make plans whose asset values declined significantly appears as if they had not lost as much value. The market losses of 2008 and 2009 were damaging and real, and the lost value in DB pension plans needs to be rebuilt through new employer contributions. To pretend these losses did not happen while allowing new pension promises to accrue is irresponsible.

Like so many other changes in this bill, these are drafted as temporary changes. Experience strongly suggests that if these provisions are enacted once into law, they will become “extenders” in the future, resulting in a permanent weakening of the funding of DB pension plans.

This is like planting a time bomb, with future retirees as potential victims. Years from now, when a firm goes bankrupt, the press will run heart-rending stories of retirees forced by the PBGC rules to take haircuts to their pensions, in which they receive less than they were promised over a lifetime of work. The reporter will wonder, “Why didn’t anyone object at the time, when Congress weakened the requirements that employers fully prefund the promises they make to their retirees?”

I am objecting. Will anyone in a position of power say no?

Tip for reporters: These legislative provisions are almost always driven by 1-4 specific firms. There’s a story waiting for the reporter who can uncover which firms benefit from each provision, and which Members of Congress are responsible for the insertion of those provisions into the draft House bill.

(photo credit: Airline workers on the tarmac by ellenm1)

The Hypocrisy Act of 2010

The House will soon vote on a new version of the “tax extenders+ bill,” which is formally labeled H.R. 4213, The American Jobs and Closing Tax Loopholes Act of 2010.

Must … not … call it … Stimulus IV.

A better name might be The Hypocrisy Act of 2010. This bill is getting far less press coverage than it deserves.

Precis of the bill (bill text, summary)

The bill:

- increases infrastructure spending by $26 B over ten years;

- extends a raft of expiring tax provisions, mostly for one year

- provides funding relief for certain employer pension plans;

- raises a bunch of taxes, mostly on businesses and a certain kind of partnership income called “carried interest;”

- extends unemployment insurance benefits, increasing federal spending by $47 B over the next two years;

- increases Medicare payments for doctors through the end of 2013 for eighteen months at a $63 B cost;

- increases health insurance subsidies for the unemployed (through “COBRA”) by $8 B over the next two years; and

- increases federal Medicaid spending by $24 B for a six-month policy change.

CBO gives us the net budgetary effects of the bill over the 11-year period 2010-2020:

- $40 B net tax increase;

- $174 B spending increase;

- $134 B deficit increase.

I count at least four reasons this bill deserves the title The Hypocrisy Act of 2010.

1. It would increase the deficit by $134 B, violating the much-ballyhooed PAYGO law.

The annual extension of expiring tax provisions is a fairly routine legislative matter, with an accompanying annual partisan fight about whether the revenue loss from extending these tax cuts should be offset by other tax increases or spending cuts.

Adding on another $174 B of spending without offsets is far from routine. $174 B is a lot of taxpayer money.

Here is Speaker Pelosi on February 4, 2010:

So the time is long overdue for this to be taken for granted. The federal government will pay as it goes. That we will be on a path of deficit reduction and that every action that we take and any bill that we take will have to meet the test: Does this reduce the deficit? Does this create jobs? Does this grow our economy? Does this stabilize our economy well into the future?

Central to all of that and a very strong pillar of fiscal responsibility is this PAYGO legislation that we have here today. I couldn’t be more thrilled for what this means about the fundamentals of how we govern, how we choose, and how we honor our responsibility to future generations to reduce the deficit.

In February the Speaker said, “and any bill that we take will have to meet the test: Does this reduce the deficit?” For this bill, no. The amendment being considered by the House would result in a $134 B increase in the budget deficit, a direct result of a $174 B increase in entitlement spending. So much for “the federal government will pay as it goes.”

A secondary irony is the one-sided nature of the deficit impact. For years Democrats have accused Republicans of hypocrisy for their embrace of a pay-as-you-go rule only for spending increases and not for tax cuts. This bill does the opposite, which I understand is the result of internal dynamics within the House Democratic Caucus. It appears House Democrats refused to support a bill that resulted in a net reduction in taxes, but apparently were OK with increasing government spending by more than $100 B without offsetting it.

I wonder how moderate “Blue Dog” House Democrats, who led the charge for a PAYGO House rule change and then a PAYGO law, will justify voting for this deficit increase driven by increased entitlement spending. Some will certainly argue the spending (further extending unemployment benefits and health insurance subsidies for the unemployed, and further increasing infrastructure spending) is necessary or even vital. That judgment is supposed to be independent of whether the deficit impact should be offset by other spending cuts or tax increases. PAYGO doesn’t provide a “good policy” exemption to offsetting spending increases or tax cuts. This “vital policy” argument is a punt to avoid having to make hard choices.

When a similar PAYGO inconsistency was pointed out in the Senate, moderate Senate Democrats took refuge in the political cover provided by a few moderate Senate Republicans who supported the bill. But that merely makes the hypocrisy bipartisan since some of those Republicans also claim to support PAYGO.

By the way, you can add much of the +$174 B onto the ultimate cost of the stimulus law, since the bulk of it results from extensions of provisions within that law. The ultimate cost of the stimulus and its extensions is approaching an even trillion.

2. The health care laws would no longer reduce the deficit.

According to CBO, the amendment being considered by the House would increase Medicare payments to physicians over the 3.5-year 18-month period from June 1 of this year through the end of 2013 2011. This 3.5-year 18-month “doctor’s fix” would increase federal spending by $63 B over the next decade. And that leaves the “doctor’s fix problem” unsolved after 2013 2011, necessitating even more expensive subsequent “fixes.”

CBO estimated that the two health laws enacted earlier this year would reduce federal deficits by $143 B over the period 2010-2019. This $63 B is just the beginning of the Medicare doc fix spending. Another 2-3 years of that policy should easily swallow the remaining $80 B of deficit reduction, leaving the net result of (two health care laws + repeated short-term increases in Medicare physician spending) to increase significantly the deficit over the next decade.

The Administration and Democratic Congressional Leaders knew they were leaving this additional Medicare spending out when they enacted the two health care laws in March. Back then they needed to tell their Members they were voting for deficit-reducing legislation and they couldn’t make the numbers add up, so they kicked the Medicare doctors can down the road to now.

3. Double-counting increased oil spill liability payments

The House amendment would extend and quadruple a tax from 8 cents per barrel to 32 cents per barrel. These funds are earmarked to prefund the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund. In theory, balances are accumulated in the trust fund as revenues are paid in, and the fund is drawn down when there’s a big spill (like we have today). So far so good.

The hypocritical part is claiming that these higher per-barrel taxes will both increase the balances of the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund and reduce the deficit. You can claim one or the other, but you cannot legitimately claim two purposes for a single dollar. This is not a technical or legal violation, as it is allowed under the budget rules. But the bill summary provided by Chairman Levin Rangel says,

To ensure the continued solvency of the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, the bill would increase the amount the oil companies are required to pay into the fund.

And the CBO/JCT score incorporates the increased revenues in its calculation of the total deficit effects of the bill. Claiming both is a foul.

4. The not-so-temporary stimulus

The stimulus law “temporarily” increased federal Medicaid subsidies to state governments. These subsidies are scheduled to expire December 31, 2010. The new House amendment would extend those subsidies for another six months, at a cost of $24 B. Who wants to wager against them being extended for at least another six months as June 30, 2011 approaches? Governors from both parties will be pressing Congress for another extension, as they are undoubtedly doing now.

I will not make the same argument for the extended unemployment insurance and health insurance (COBRA) subsidy benefits, because I think those provisions eventually will be allowed to expire once the unemployment rate declines significantly.

This increased federal Medicaid spending, however, looks and feels like it’s well on the way to becoming an additional +$50 B per year in federal spending, forever. The stimulus was sold as a temporary deficit increase.

Postscript

Every extenders bill contains special interest goodies. Here are my favorite three from this bill:

- extending the 7-year depreciation rule for “motorsports entertainment complexes” Go NASCAR. Go monster trucks.

- extending the one-year expensing rule for the first $15-20 M of productions costs for film and TV producers in the U.S.; and

- repeal of a provision designed to limit Medicare payments to nursing homes that were gaming the system and the taxpayer.

When you hear someone argue that the $134 B deficit increase and PAYGO violation are OK because the policies contained within the amendment are vital, ask them about these three provisions of The Hypocrisy Act of 2010.

(photo credit: Free Parking Jackpot by teamjenkins)

Employment trend vs. employment level

Yesterday we looked at the difference between the rate of growth of GDP and the level of GDP. Both matter. Today I’d like to do the same for employment.

Before I do, I want to point to some posts from Greg Mankiw (here, here, and here) that suggest a different hypothesis about the trend line for potential GDP. Demonstrating why he has the best selling economics textbook, Greg clearly explains the difference between a trend stationary forecast of GDP and the unit-root hypothesis. My post was based on a

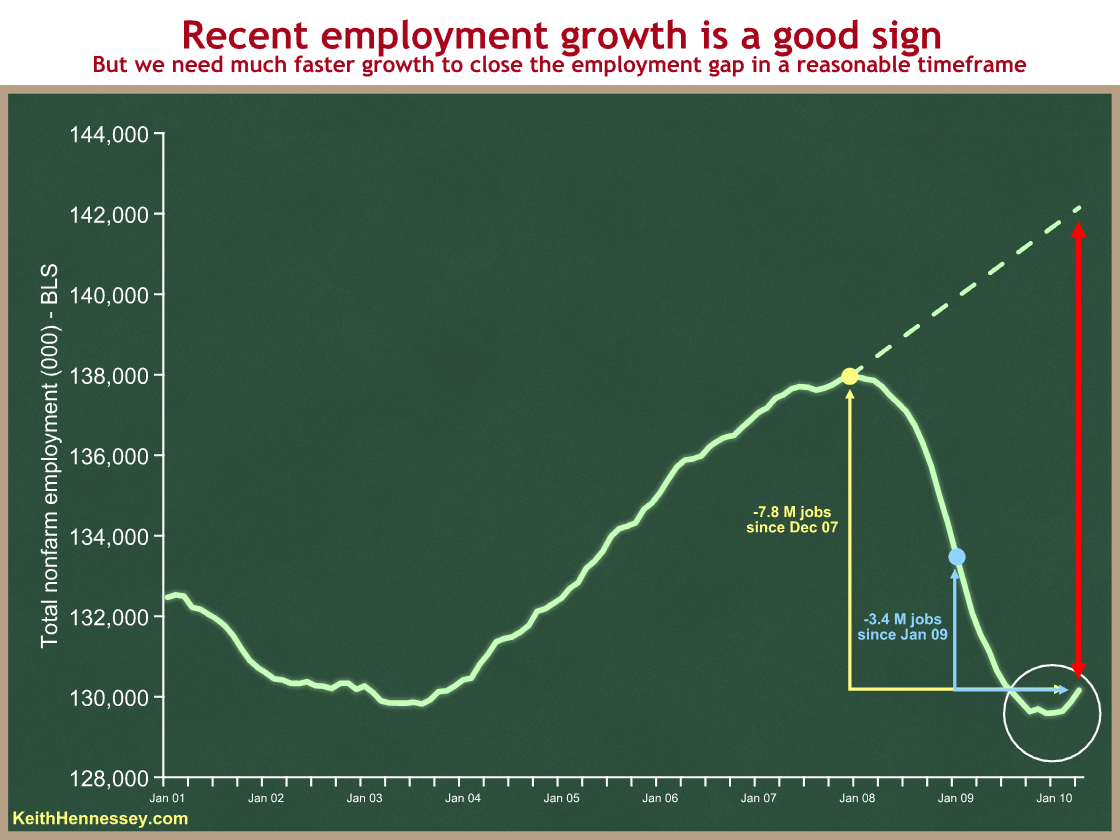

Here is the parallel graph for payroll employment (source: BLS, dotted line is my overly simplistic trendline):

When the President spoke Tuesday in Youngstown, Ohio, he emphasized the recent trend: the upturn in net job creation over the last four months, and the significant employment jump last month:

We gained more jobs last month than [at] any time in four years. And it was the fourth month in a row that we’ve added jobs – and almost all the jobs are in the private sector.

This statement is accurate in all respects. The President is right: the recent upturn in net payroll employment is clearly good news. Unlike his premature celebration last August, this new trend looks good and should be highlighted.

The +14K and +39K figures for January and February back up the President’s use of “fourth month in a row.” But as a practical matter it’s basically a flat line from last November through this February, with a positive upturn in March and April.

We have a similar issue with employment growth as we did yesterday with GDP growth. While the slope of the line is important, so is the size of the gap between where we are and where we could be. I have shown three measures of that gap, with yellow, blue, and red arrows. You can see that the U.S. economy is still employing 3.4 million fewer people now than when the President took office in January 2009. 7.8 million fewer people are working now than at the employment peak in December 2007. And given that the potential labor force grows as our population grows, the gap between where we are now and “every American who wants to work is working” (e.g., 5% unemployment) is even larger.

So the past two months of net job growth are good news but do not yet justify a victory lap. The unemployment rate is still 9.9%, and we need much faster job growth than +290K jobs/month to close that gap in any reasonable timeframe.

Here’s a back-of-the-envelope calculation I did a couple of weeks ago when the April jobs report came out:

- We’re down about 7.8M jobs (payroll survey) from the peak when we were at full employment in December, 2007.

- We added 290K jobs last month. What’s the trend?

- 66K of those 290K were census workers. Those are temporary jobs that will go away.

- 290K – 66K = 224K

- We need to create about 150K jobs per month just to keep up with population growth and roughly hold the unemployment rate constant. (Some say between 100K and 150K.)

- 224K – 150K = +74K. If we use 100K then we’re at +124K.

- So if April’s numbers became a trend, we’d be creating about 75K – 125K more non-temporary jobs each month more than needed to keep up with population growth.

- 7.8M / 100K = 78-ish months

So if March’s data were to become a trend, we would be looking at 5-6+ years to get back to something like full employment.

Now I’m not predicting that long of a recovery period. Instead, I’m trying to show that, while +290K jobs in April is a good number, and it is the most jobs created in any single month in four years, we need a much more rapid pace of net job creation for the foreseeable future to close the employment gap in a reasonable time frame. And the “best in four years” shouldn’t surprise you, as we should expect more jobs to be created during a recovery than when the economy is at or near full employment.

I expect the two parties will emphasize these two different aspects of the employment picture over the next six months of the election cycle:

- The President and Democrats: Things are getting better now. The economy is creating net new jobs.

- Republicans: Things are still bad. The unemployment rate is still high.

Barring a negative economic shock, both statements are likely to be correct for the remainder of this year. We’ll see whether voters care more about the level or the trend.

Update: Menzie Chinn critiques my graph, and he makes some excellent points. I was overly simplistic in my trend line (the dotted line) to the point where, were I writing this post anew, I would leave it out. I stand by my qualitative conclusions, and the point about trend vs. level is still one of the most important in this policy debate. But I don’t think the “5-6+ years to get back to something like full employment,” nor the dotted green nor red lines on the graph above, are solid enough for me to continue defending them. I stand corrected, and thank Dr. Chinn for his post.