Tax cuts did not cause the financial crisis

In Monday’s debate Secretary Clinton said:

We had the worst financial crisis, the Great Recession, the worst since the 1930s. That was in large part because of tax policies that slashed taxes on the wealthy, failed to invest in the middle class, took their eyes off of Wall Street, and created a perfect storm.

Supplementing Glenn Kessler’s excellent analysis in today’s Washington Post, let’s examine Secretary Clinton’s argument that the Bush tax cuts “in large part” caused the 2008 financial crisis.

The Kessler column cites Alan Kreuger and Simon Johnson, offered by the Clinton campaign to back up her argument. Neither does. Each defends his own reinterpretations of what she might have meant or could have said.

Folks on the left often have other reasons to oppose (or to have opposed) the Bush tax cuts, and I am happy to debate those points. Similarly, the argument that President Bush and Congressional Republicans “failed to invest in the middle class” is a common refrain. But those arguments are separable from whether these policies caused or contributed to the financial crisis. To me linking tax policy to the crisis is nonsensical, as is the “failed to invest in the middle class” causal linkage to the crisis. The “in large part” further amplifies her error.

Some (e.g., Simon Johnson) argue that higher debt levels restricted fiscal flexibility in responding to the crisis. I was enmeshed in the design, proposal, enactment, and initial implementation of all financial crisis rescue actions. With debt then at 38% of GDP, fiscal flexibility did not constrain our financial rescue efforts in the last months of the Bush Administration.

As Kessler points out, the same appears to be true for Team Obama’s big initial macroeconomic recovery effort, the early 2009 fiscal stimulus. Larry Summers’ December 15, 2008 transition memo to then president-elect Obama says their fiscal stimulus recommendation was constrained by their inability to figure out how to spend money any faster, not by debt levels.

More importantly, whether higher debt resulting from the Bush tax cuts (and other spending policies) constrained the response to the crisis is irrelevant, because Secretary Clinton claimed these policies caused the crisis, not that they made it harder for policymakers to respond once the crisis had occurred. “Tax policies that slashed taxes on the wealthy,” she argued, “created a perfect storm.”

Others argue: The Bush tax cuts increased high-end income, and increased income inequality —> increased purchase of mortgage-related lending by the rich –> credit/mortgage bubble –> over-leverage –> financial crisis.

There are at least two problems here.

- Income inequality has been increasing for more than three decades, and the housing bubble began in the late 90s, a few years before the initial round of Bush tax cuts. Her timing doesn’t work.

- The most prominent explanations for the 00s’ credit bubble point instead to some combination of increased global capital flows (mostly from China and oil-producing nations to the U.S. and Western Europe) and U.S. monetary policy. I have not seen anyone argue that in an open economy like ours the 2001 or 2003 tax cuts and resulting higher incomes for the rich caused either the credit bubble or the bubble in housing-related financial assets.

Many on the policy and political left argue the 2008 crisis was “Wall Street’s fault, stemming from greed, arrogance, stupidity, and misaligned incentives, especially in compensation structures.” Had she stuck with this argument Secretary Clinton would have been able to point to others who make similar arguments and she would have had a more defensible position (albeit one with which I still disagree). Senators Sanders and Warren, Brooksley Born, and Phil Angelides all fall into this camp.

Instead, her argument that fiscal policy “in large part … caused a perfect storm” broke new ground. I think this argument was politically driven and this new ground is intellectual quicksand.

U.S. fiscal policy, including the Bush tax cuts, did not cause or contribute to the 2008 financial crisis. Secretary Clinton was incorrect in arguing that it did.

Response to Mr. Trump on steel

In Pennsylvania today Donald Trump said, “When subsidized foreign steel is dumped into our markets, threatening our factories, the politicians do nothing.”

This is false. President Bush imposed tariffs on imported steel in 2002. A month ago the Obama Administration imposed duties on Chinese steel of more than 200 percent and up to 92 percent on steel imported from South Korea, Italy, India, and Taiwan.

Steel is an intermediate good. When you raise protectionist barriers against imported steel as Mr. Trump threatens, you temporarily help U.S. steelworkers. You also raise input prices for American firms that use steel to build bridges and buildings and make cars, and trucks, trains and train tracks, appliances, ships, farm equipment, drilling rigs and power plants, and tools and packaging. Higher input costs hurt American workers in those factories and on those construction sites.

Mr. Trump should ask the workers who make dishwashers at Whirlpool’s plant in Findlay, Ohio whether they’re in favor of more expensive steel. Or he can ask the John Deere workers who use steel at their factories in Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. Or the auto workers at almost any U.S. car and truck assembly line. Raising prices for imported steel hurts all of these American workers.

Yes, the Chinese are selling steel in the U.S. at a low price, called “dumping.” Yes, this hurts the owners and employees of U.S. steel manufacturers. It also helps many other American workers and even more American consumers. And the Obama Administration is using the tools in current law to respond to the Chinese actions.

Trump: “A Trump Administration will also ensure that that we start using American steel for American infrastructure. … We are going to put American-produced steel back into the backbone of our country. This alone will create massive numbers of jobs.”

No, it won’t, and the downside is it would cost taxpayers more. Put another way, any given amount of tax dollars will build less infrastructure. We’ll repair fewer bridges but, by golly, the fixed ones will have American steel. I’d rather get the best value for every tax dollar we spend on infrastructure, thus ensuring we fix as many bridges as possible.

Mr. Trump’s lines may sound good in steel country, but his policies would harm other American workers, drivers, and taxpayers. On the whole Donald Trump’s steel policy would be bad for America.

I oppose Donald Trump

I will not vote for Donald Trump for the Republican presidential nomination. If he wins the nomination I will not vote for him for President.

This is not a tough call.

Donald Trump is an ignorant, unprincipled, amoral policy lightweight opposed to free market capitalism and limited government.

- His ignorance of economic and national security issues is breathtaking. He makes up most of his policy views on the fly in interviews. He knows far less about policy than does a regular Wall Street Journal reader, and he cannot hold a coherent in-depth conversation about the economy or America’s role in the world. I don’t expect him to be a national security expert but it would be nice if a future commander-in-chief understood the strategic importance of NATO rather than thinking of it as a potential revenue source. In transcripts of two recent interviews he reminds me of students who try to answer questions in class when they have not done the reading. He is faking it on policy, and not that well.

- He is not doing his homework. I don’t blame him (much) for starting his campaign as a policy novice. Yet he appears to be no better informed today than when his campaign began. Policy is serious, hard work. He shows no interest and no effort in learning anything about the issues and decisions he might face as President. As a result he babbles in interviews, avoids Q&A sessions with voters, and changes the subject whenever he is stumped (several times per interview on average). He should be improving over time and he’s not. Even if he intends to reject the advice of experts and be an outside-the-box thinker, he should at a minimum understand what he is rejecting and where that will lead him.

- His policy views are cartoon-like when not entirely absent. Shouting STRENGTH is not a policy. His views seem to be unmoored by any intellectual structure or philosophical approach. He is unprincipled: he appears to view the world through dual lenses of transactions and of people he likes and dislikes. He treats other nations as competing firms and acts as if America’s only overseas interest is in maximizing revenue streams paid by foreign governments. His fiscal solutions are to cut waste, fraud, and abuse and to get other nations to pay America for military protection. He wants to disengage from the Middle East, destroy ISIS, and take Iraqi oil. America faces far more important questions than who will pay for a wall, and economic policy is more than renegotiating trade agreements.

- He promises strong but amoral leadership. He promises to make America great again, but great alone is insufficient. America must also be good. A President’s job is in part to make value choices and he cannot explain his values. I know what the other nominees think a good America looks like. All I know about Mr. Trump’s America is that it will have a huge wall and new trade deals.

- To the extent he has expressed views on economic policy I strongly disagree with them. I want to like his tax cuts but at some magnitude you also have to propose accompanying spending cuts. He threatens a global trade war while I am a free trader. By ruling out changes to Social Security and Medicare he would guarantee massive future tax increases. He has supported single payer health care reform. He boasts that he would order firm leaders to build their factories in the U.S. and then threatens to punish them if they do not. Business leaders, not politicians, should be deciding where to invest their firm’s capital. He seems to think of the federal government as a big firm; it’s not. I have yet to see an instance of a policy view from him consistent with free market capitalism and limited government intervention in the economy.

Donald Trump is dangerous.

- He has created conditions at his rallies that led to violence, then winked after it occurred, encouraging even more. He is not solely responsible for this outcome. Left-wing provocateurs are the flint while he provides the tinder. Together they spark violent outbursts. Part of being a political leader is taking responsibility to tamp this down whether or not you caused it. Instead he escalates.

- He seeks out and provokes conflict. So far he has alienated 1.6 billion Muslims and he got into an argument with the leader of 1.25 billion Catholics. He claims to be a counterpuncher but kicked off his campaign by labeling most Mexicans as rapists. That was not a counterpunch. Every day he is in a new fight. In a political campaign this is dispiriting. In the Oval Office this behavior would place American lives at risk.

- He sounds like a tyrant. I worry he could (try to) become one. His instincts and rhetoric lean authoritarian. He praises foreign despots and characterizes their repression of dissent as strength. I question his commitment to freedom and the rule of law.

- His poor judgment and lack of self discipline are astonishing. He could start a war by acci-tweet. I will not vote to give control of nuclear weapons and the world’s most powerful military to a man who trolls on Twitter after midnight.

Donald Trump acts like a eighth grade bully.

- He is vulgar.

- He mistakes bullying for strength.

- He is bigoted—against women, against certain religions and nationalities. This is not political incorrectness. Mel Brooks movies and George Carlin skits are politically incorrect. Donald Trump’s insults are just crude and self-serving. Whether he is actually bigoted or just playing to the crowd is irrelevant. The effect is the same and some people will follow his repulsive lead.

- He lies frequently and apparently without compunction. To support his views he cites as evidence “I read it on the internet.”

- He personalizes every professional disagreement, smears his opponents with innuendo, and facilitates others who do the same. No matter who is the counter party, public arguments with him invariably finish at a lower level than they began. He drags all of us down into the muck.

I had no idea how difficult the job of president was until I saw it up close. For more than six years and through hundreds of briefings I helped advise a president and coordinate the implementation of his economic policy decisions. A successful president must be smart, disciplined, and tireless. He or she has to use expertise effectively and to make sound decisions based on core principles and values. At the same time being president is not just about effectiveness and efficiency, it’s also about moral leadership and character.

Donald Trump lacks the character, the values, and the sound judgment essential to fulfill this awesome responsibility. He is unqualified and unfit to be President of the United States.

Clinton versus Sanders on auto loans

I have not written publicly in a year. I guess it’s time.

Last night on the CNN debate in Flint, Michigan, Secretary Clinton said of Senator Sanders,

I voted to save the auto industry. He voted against the money that ended up saving the auto industry. I think that is a pretty big difference.

The Michigan primary is tomorrow so this is a big deal. I have no dog in a primary fight between Secretary Clinton and Senator Sanders.

During the time in question I was serving as Director of the White House National Economic Council staff for President Bush and was heavily involved in this issue.

Here is the full Clinton quote:

CLINTON: Well — well, I’ll tell you something else that Senator Sanders was against. He was against the auto bailout. In January of 2009, President-Elect Obama asked everybody in the Congress to vote for the bailout.

The money was there, and had to be released in order to save the American auto industry and four million jobs, and to begin the restructuring. We had the best year that the auto industry has had in a long time. I voted to save the auto industry.

(APPLAUSE)

He voted against the money that ended up saving the auto industry. I think that is a pretty big difference.

…

Now let me get back to what happened in January of 2009. The Bush administration negotiated the deal. Were there things in it that I didn’t like? Would I have done it differently? Absolutely.

But was the auto bailout money in it — the $350 billion that was needed to begin the restructuring of the auto industry? Yes, it was. So when I talk about Senator Sanders being a one-issue candidate, I mean very clearly — you have to make hard choices when you’re in positions of responsibility. The two senators from Michigan stood on the floor and said, “we have to get this money released.” I went with them, and I went with Barack Obama. You did not. If everybody had voted the way he did, I believe the auto industry would have collapsed, taking four million jobs with it.

Key conclusion

While she gets a few details wrong, Secretary Clinton’s story is roughly correct right up until you get to her punchline. Then she blows it. In addition she ignores a more important vote from six weeks earlier in which she and Senator Sanders voted the same way, in favor of helping the auto industry.

Secretary Clinton’s attack misleads Michigan voters and others who supported the auto loans. She is playing semantic games in an attempt to create a policy difference where none exists.

As with all things Clinton, you have to parse her phrasing carefully. The sleight-of-hand is quite clever.

The details

Three votes matter:

- On October 1, 2008, Senator Clinton voted for TARP while Senator Sanders voted against it. TARP became law.

- On December 11, 2008, Senators Clinton and Sanders both voted for cloture on the motion to proceed to a bill to provide loans to the auto industry, a Senate attempt to marry up legislation with a bill passed by the House the previous day. That cloture vote failed and the bill died.

- On January 15, 2009, Senator Clinton voted against a resolution of disapproval to release the second $350 B of TARP funds while Senator Sanders voted for this resolution. The vote failed and the resolution died, thus allowing the full TARP funding to be used by President Obama and his team when they took over. This is the vote she highlighted last night.

There are two key legislative realities to understand about these three votes.

- The first and third votes were principally about TARP and not about auto loans. The second vote, the December vote on which Clinton and Sanders agreed, was clearly about the auto industry.

- The January vote was substantively meaningless since everyone knew that President Bush would have vetoed the resolution had it passed, and that he could have easily sustained his veto. This vote was symbolic, not substantive.

From a Michigan perspective Senator Sanders cast one “wrong” vote that in hindsight was essential to helping the auto industry: he voted against TARP in September 2008 while she voted for it. Had TARP not become law there would not have been funds available for the initial Bush auto loans in late December or for the Obama auto loans the following spring. The logic Secretary Clinton used last night applies well to her September 2008 vote, which differed from that of her primary opponent.

But the logic applies to that vote only when we look at its practical effect in hindsight. At the time no one anticipated using TARP funds for the auto industry so she cannot argue that Senator Sanders chose in September not to help Detroit. Since she did not mention the September vote last night, she did not make this mistake, but we’ll see that she did make a variant of it when characterizing the January vote.

On the vote most directly applicable to the auto industry, the one in December, Senators Clinton and Sanders voted the same way: aye. They can both legitimately argue that with these votes they explicitly chose to try to help Michigan. Despite their votes that legislation failed, leading to President Bush’s decision shortly thereafter to use TARP funds for auto loans.

By mid January the initial round of TARP loans to GM, Chrysler, and their finance companies was underway. We (the Bush team) coordinated with the Obama team to have President Bush trigger release of the second $350 B of TARP funds in his last few days, a mechanism in the TARP law enacted three months prior. We did this before January 20th so President Obama would have the additional funds available on day one if a crisis struck, and so that he didn’t have to take the political hit for vetoing a resolution of disapproval if necessary.

That release triggered the resolution of disapproval mechanism we created in the TARP law. In theory this process would allow the Congress to stop release of the second $350 B by enacting a resolution of disapproval. In practice everyone knew this was impossible. Even if the House and Senate had passed the resolution (and we were confident they would not), President Bush would have quickly vetoed it and we let people know that. To override that veto would have required more than two-thirds of the House and more than two-thirds of the Senate. That scenario wasn’t just infeasible, it was legislatively impossible. Every Senator voting on the resolution of disapproval knew, with certainty, that their vote would not have any practical effect on the release of the second $350 B or the funds available for banks, President Obama’s subsequent mortgage relief, or a second round of auto loans.

This is the key to understanding Secretary Clinton’s sleight-of-hand last night. She is technically correct when she said, “If everybody had voted the way he did, I believe the auto industry would have collapsed, taking four million jobs with it.” If every House and Senate member had voted to disapprove the release of these funds, then a Bush veto would have been overridden and there would have been no funds available for a second round of auto loans.

But in practice these votes were symbolic rather than substantive, and they were symbolically about TARP, not auto loans. Only now, in hindsight, can she frame them as having been about the auto industry. I am glad she voted symbolically the way she did, in support of and defense of TARP, and I disapprove of Senator Sanders’ no vote. But it is absurd for her to claim both that with this vote Senators Sanders chose not to help the auto industry, and that this January no vote could have had any practical negative effect on Michigan.

Upon careful examination her quote is quite carefully constructed. “I voted to save the auto industry. He voted against the money that ended up saving the auto industry. I think that is a pretty big difference.”

A fair reading instead would be:

- She voted in September 2008 for legislation to rescue the global financial system while he voted against it. Although no one knew it at the time, they later learned this vote provided the funds essential to save GM and Chrysler from collapse.

- In December 2008 they both voted for legislation specifically aimed at helping the auto industry. That legislation failed.

- In January 2009 she cast a substantively meaningless but symbolically important vote supporting TARP while he cast a parallel vote opposing TARP. That vote had no practical effect on the auto industry, and at the time was not framed as a choice to help or not help autos. She is now misleadingly reinterpreting it as a substantively important vote against the auto industry and the State of Michigan.

I hope this clarifies things a bit.

Keith Hall, the new CBO Director

I’d like to associate myself with Dr. Charles Blahous’ endorsement of Dr. Keith Hall to be the new director of the Congressional Budget Office. Budget Committee Chairmen Tom Price and Mike Enzi made a strong pick by choosing Hall. I know him from his time at the Council of Economic Advisers and watched him from afar when he ran the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In particular I agree with this Blahous quote:

The chairmen needed to find someone with impeccable academic credentials, and they did (Hall not only has his economics PhD from Purdue, but also served as chief economist for the White House’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA)). They needed to find someone with the demonstrated ability to manage CBO, and they did (Hall previously ran the Bureau of Labor Statistics). They needed someone manifestly even-tempered and evidence-driven, and they got that in spades. Hall will quickly come to be recognized more widely as the soft-spoken and objective analyst his associates already know him to be. He has been particularly good as a witness delivering congressional testimony, where his “just the facts” style suits what Congress needs from CBO.

I am optimistic that Dr. Hall will continue the excellent work of outgoing director Dr. Doug Elmendorf and further reinforce CBO’s role as a highly credible, nonpartisan, and unbiased referee in the budget process.

Will the last moderate fiscal Democrat please turn out the lights?

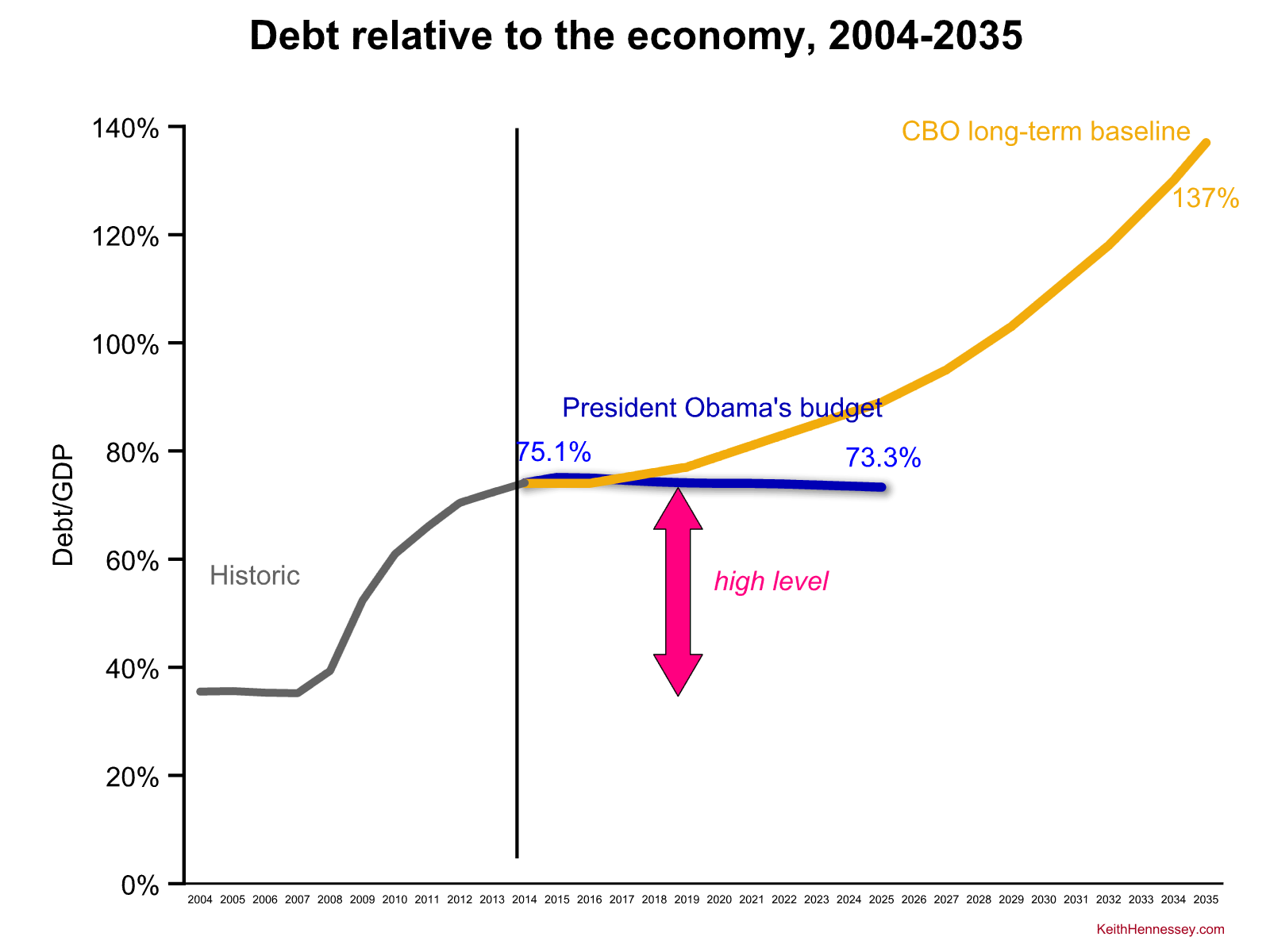

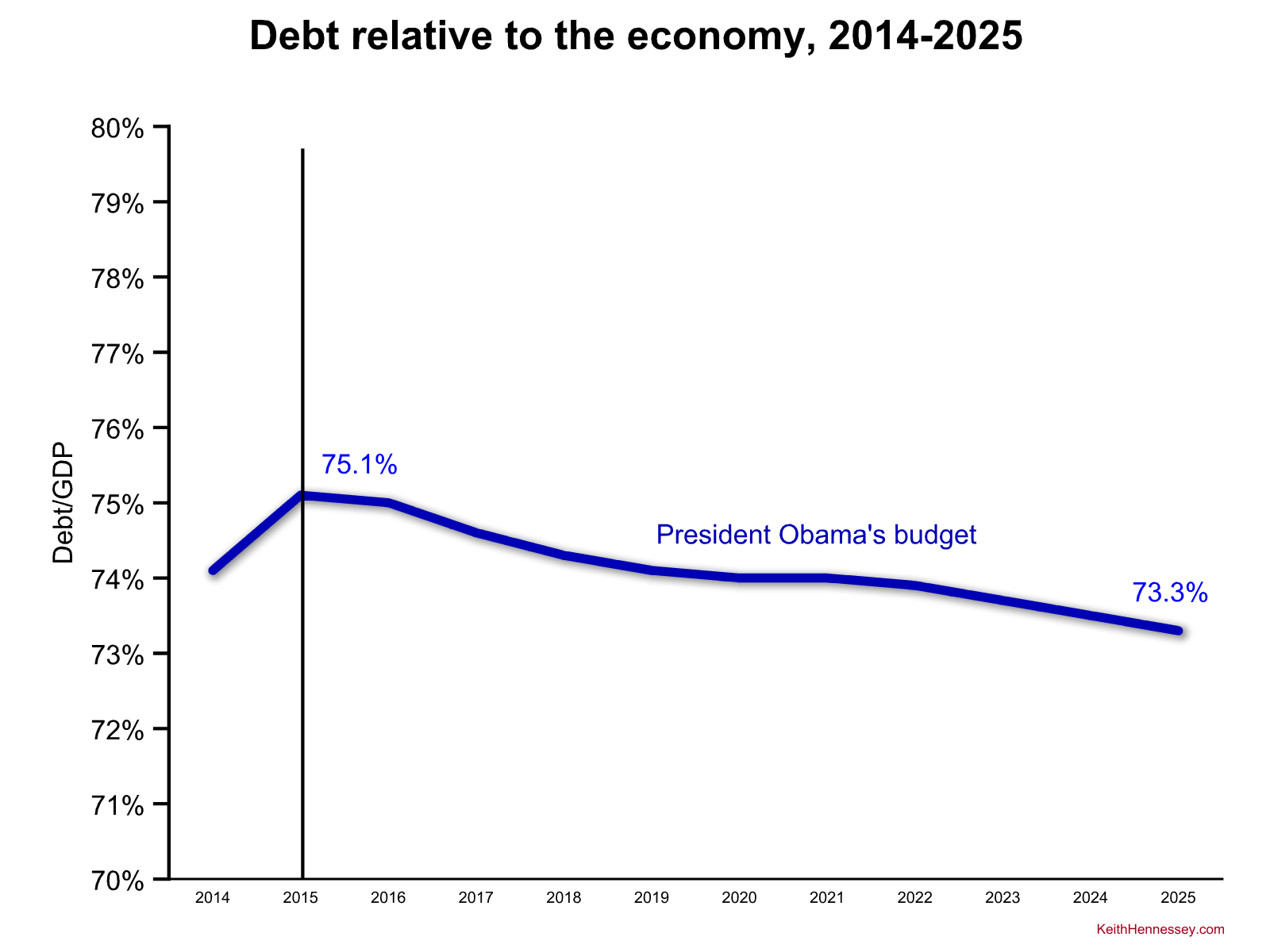

In his new budget President Obama once again proposes to flatten debt/GDP, to stabilize it over the next decade at a high level.

But wait, you say. That’s not stabilizing. That’s not “flat” debt/GDP, that’s a declining path. And it doesn’t look like a high level. If we zoom out we gain additional perspective. Let’s add 10 years of historical data and CBO’s projected long-term baseline forecast.

But wait, you say. That’s not stabilizing. That’s not “flat” debt/GDP, that’s a declining path. And it doesn’t look like a high level. If we zoom out we gain additional perspective. Let’s add 10 years of historical data and CBO’s projected long-term baseline forecast.

Now you see why I said “at a high level.” Under both a current policy baseline and the President’s budget, debt/GDP is in the mid-70s for the next five years, more than twice as large a share of the economy as it was pre-financial crisis. (The same is true if we go back even farther in time. The pre-crisis average debt/GDP varies between 34 and 40% of GDP for any start year from 1965 through 2007.) While the long-term baseline starts to climb about five years from now, the President proposes to keep it roughly flat through the next decade. (more…)

Response to OMB Director Donovan on dynamic scoring

OMB Director Shaun Donovan criticized House Republicans today for their rule change on dynamic scoring. I’ll skip the preliminaries and offer responses to his main critiques.

OMB Director Shaun Donovan: “Using dynamic scoring for official cost estimates would risk injecting bias into a broadly accepted, non-partisan scoring process that has has existed for decades.”

KBH:

No, the new rule attempts to eliminate an oversimplifying assumption that we know is incorrect and biased in a limited number of cases where that bias is large enough to matter. We know that some policy changes can increase (or reduce) the size of the economy, and that to assume otherwise is wrong. The longstanding scoring process is biased against policies that would increase economic growth, and biased for policies that would shrink the economy. The size of the effect of large and broad-based reductions in tax rates is uncertain, but we’re pretty darn sure it’s not zero. Certain immigration reforms would increase domestic labor supply and increase economic growth. More accurate scoring would incorporate both types of effects.

Donovan: “[D]ynamic scoring requires CBO and JCT to make assumptions in areas with unusually great uncertainty.”

KBH:

- Yes, these assumptions are uncertain. So were CBO’s estimates of short-term fiscal multipliers from the 2009 stimulus law. CBO assumed (guessed) that the effect on short-term GDP of increasing government of purchasing goods and services by $1 could range from 50 cents of increased GDP on the low end, to $2.50 of increased GDP on the high end. (See Table 2 here and this paper.) That’s a big range that didn’t dissuade Team Obama from arguing that fiscal stimulus would increase GDP growth.

- Is it better to be precisely wrong or imprecisely right? I’m generally for the latter, which is what this rule change would encourage. We know that assuming zero GDP effect from large fiscal policy changes is incorrect. I think it’s an improvement to move to a new non-zero point estimate even if that means we have to accept wider error bounds.

- The way you get better at narrowing these uncertainties is to do more estimates and to learn by doing.

Donovan: “Dynamic scoring would require CBO and JCT to make assumptions about policies that go beyond the scope of the legislation itself.”

KBH:

- Yes, just like they had to do on fiscal stimulus in early 2009. They had to make an assumption then about how the $800+ B of increased debt would be financed in the future. They also had to make an assumption about whether the Fed would turn the monetary policy dial differently after Congress had pulled hard on the macro fiscal policy lever. Nothing new here, they’ll have to do for a few more bills what they have been doing elsewhere for quite a while.

Donovan: “Dynamic scoring can create a bias favoring tax cuts over investments in infrastructure, education, and other priorities. … The House rule would not apply to discretionary spending, ignoring potential growth effects of investments in research, education, and infrastructure.”

KBH:

- So you’re opposed to dynamic scoring for policies you don’t like, but OK with it for policies you do like? Hmmm…

- This is almost a conceptually valid critique but it’s a little hard to see how one would practically expand the new rule to apply to discretionary spending. The House rule would only apply dynamic scoring to big fiscal policy changes, those with an aggregate static budget impact bigger than 0.25% of GDP (>$45 B per year in 2015). That high de minimis threshold is a smart practical limitation so that CBO doesn’t have to worry about the growth impacts of the cars-for-crushers program or a $50M increase in spending for pet project X. But since nobody is proposing adding >$45B/year to discretionary spending, this limitation in the new rule has no practical impact.

- But the House rule doesn’t create a bias for tax cuts. It eliminates a pre-existing bias against very large policy changes that would expand the supply side of the economy, including but not limited to broad-based reductions in tax rates.

The Obama Administration’s position seems to be:

- We like incorporating the short-term growth effects of increased government spending (fiscal stimulus);

- In that case we’re OK with estimators making assumptions that go beyond the scope of the legislation (Fed reaction to fiscal stimulus);

- We’re OK with lots of estimating uncertainty when it applies to policies we like (big ranges for short-term fiscal multipliers);

- We’re happy to trumpet the growth benefits, as estimated by CBO, for policies we like such as the Senate immigration reform bill;

- But we don’t want to incorporate long-term supply-side effects from policies we don’t like (broad-based tax relief),

- And we will label any scoring change which incorporates (but is not limited to) those policies as “biased.”

- Their goal is to preserve a longstanding scoring bias that keeps taxes probably higher than they otherwise would be if scoring were more accurate and policy neutral.

In contrast, my view is:

- Scoring should be accurate, unbiased, and policy neutral.

- The “fixed nominal GDP” estimating convention is both inaccurate and biased.

- Estimates of very large fiscal policy changes should incorporate CBO and JCT’s best judgment (not Members’ of Congress best judgment) about both the short-term demand-side GDP effects and the long-term supply-side GDP effects.

- Relaxing this fixed nominal GDP assumption should apply to all types of fiscal policy changes exceeding a certain size, whether I like them or not. The House’s >0.25% of GDP seems like a reasonable threshold.

- CBO and JCT should explain their estimating ranges and uncertainty for these dynamic estimates, as they have for short-term fiscal multipliers in the past.

- The House rule is a responsible improvement in scoring policies that makes scoring more accurate by reducing a long-standing bias.The increased uncertainty that results is worth reducing the underlying bias.

Elmendorf for CBO

The new four year term of the Director of the Congressional Budget Office begins soon. Now that Republicans will have majorities in the House and Senate, this job is entirely their call. The President is not involved. Incoming House and Senate Budget Committee Chairman Tom Price and Jeff Sessions will make this choice.

While at first blush it may seem counterintuitive, the best move for fiscal and economic conservatives is to reappoint Doug Elmendorf. If Chairmen Price and Sessions won’t do that, then I recommend they choose Kate Baicker. If any key Hill Rs want to know why I think Dr. Baicker is the best new candidate, please contact me privately. Here I’m going to focus on why I hope Chairmen Price and Sessions reappoint Dr. Elmendorf.

Dr. Elmendorf is not a conservative. He was originally chosen to head CBO by Congressional Democrats. He came from the left-of-center Brookings Institution. I think he is registered as an independent. I don’t know how he votes but I’d bet he’s a moderate/centrist Democrat.

I want to move economic policy to the right, not to the center-left. I think Dr. Elmendorf is the best pick for CBO because (a) he is unbiased and intellectually honest; (b) his background insulates his rulings and the Congressional Republicans who choose to reappoint him from accusations of bias; and, most importantly, (c) this combination greatly disadvantages the progressive Left who both dominate current economic debate within the Democratic party and who cannot refrain from intellectual overreach.

There are two ways to move economic policy debate to the right. One is to make stronger free market and small government arguments. The other is to rebut the wackiest arguments made by the Left. Congressional Republicans should do the former and lean on Dr. Elmendorf and CBO for help with the latter. Over the past few years an Elmendorf-led CBO has weakened a few key support pillars of the Left’s big government intellectual edifice, not because Elmendorf leans right but because the Left is dominant and nuts and their most outrageous arguments just beg to be debunked by a neutral referee.

- Team Obama overreached, arguing that a minimum wage increase would result in no job loss, that an increase to $10.10/hour would benefit millions and harm no one. Under Elmendorf CBO destroyed this claim, pointing out that the President’s favored policy would reduce the labor supply by about half a million workers. For once economic conservatives were on strong ground not just because we had facts and logic on our side, but also because the press repeatedly wrote that “the nonpartisan CBO said the President’s minimum wage increase would reduce the labor supply by half a million workers.” We won those debates in part thanks to an assist from a CBO that was and was described as unbiased and nonpartisan.

- Elmendorf’s CBO analyzed the reduced labor supply that would result from ObamaCare, a 1.5-2 percent reduction in hours worked. CBO applied routine analysis straight out of a microeconomics textbook. In doing so they rebutted absurd free lunch claims made by the Obama White House and their allies on the Left. And again, the press (even all the biased ones) had no choice but to report these findings as definitive, since they had no opportunity to accuse the director of Republican bias.

Had CBO been led at the time by a director chosen by Republicans, the exact same conclusions would have been dismissed or caveated by many (most?) of the press. The press coverage and public debate would have instead been about how “Congressional Republicans and their hand-picked conservative CBO Director said ______________.” The identical conclusions from a director chosen by Republicans would have had far less impact on the public debate. That is unfair. It is also an unavoidable consequence of a biased press corps that free market and small government conservatives would be foolish to ignore.

I am not arguing that Republicans should always choose a Democrat to run CBO, or that only a Democrat can have this public credibility, or that the press credibility of choosing a Democrat is worth appointing someone biased to the left. I think Dr. Kate Baicker would quickly build Elmendorf-like credibility if chosen to lead CBO. And I think Dr. Peter Orszag, chosen by Democrats to head CBO before he became President Obama’s OMB Director, ran CBO as an advocate and policy entrepreneur, not as a neutral referee.

Just as I sometimes disagree with and even yell at the fairest football and basketball refs, I disagree with some of the judgment calls Dr. Elmendorf and CBO have made. But I don’t want the ref to be biased right or left. I don’t even think a right-leaning ref would be that valuable to winning these debates, given the higher press hurdle that would be set by a biased press corps. I also think fiscal and economic conservatives benefit from an institutionally strong CBO, as the Left far more often wants to ignore arithmetic and cost-benefit tradeoffs than do the Republicans now taking the helms of the key economic committees in Congress.

I think CBO is too wedded to assuming large and unproven short-term Keynesian multipliers, but their approaches to estimating long-term tax, debt, labor, and health insurance policy changes support those of us who prioritize increasing the supply of labor and capital. As I noted earlier, an Elmendorf-led CBO showed that ObamaCare and a minimum wage increase would both reduce employment. Under Elmendorf, CBO said that increasing marginal tax rates dampens economic growth because it reduces incentives to work, save, and invest. Elmendorf’s CBO said that transfer payments reduce work incentives and shrink the labor force. In contrast to President Obama and Dr. Krugman, Elmendorf’s CBO warned that high and rising debt levels will lower future income, increase pressure for higher taxes or less defense spending, and increase the risk of a fiscal crisis at some uncertain future date. In contrast to the Piketty Fan Club, CBO’s distributional analysis showed that the burden of financing government is even more distributed toward the high end than is income, and they integrated into their analysis the effects of both taxes and transfer payments.

Many Congressional Republicans need to learn how to use CBO better. They need to actually read what CBO writes and to figure out how to ask questions of CBO and of Dr. Elmendorf that will highlight the ways in which left-wing dogma contradicts straight-up-the-middle economic analysis. If Hill Republicans learn how to do this more effectively, the debate will move rightward as the Left’s case weakens.

I hope Congressional Republicans who want smaller government and freer markets think strategically about this post. Keep CBO strong and unbiased both in fact and in appearance. Win the economic policy debate by keeping the valuable asset they now have, the public and press credibility of a fair ref who often rebuts wacky dangerous arguments made by the Left. Learn to use CBO’s analyses more effectively and to ask them the right questions. Reappoint Dr. Doug Elmendorf to head the Congressional Budget Office.

I’m with Stupid —>

A few days ago I wrote about MIT’s Dr. Jonathan Gruber’s honesty about lying to enact ObamaCare. Today I want to focus on a different part of this quote, his reference to “the stupidity of the American voter.”

In terms of risk rated subsidies, if you had a law which said that healthy people are going to pay in – you made explicit healthy people pay in and sick people get money, it would not have passed… Lack of transparency is a huge political advantage. And basically, call it the stupidity of the American voter or whatever, but basically that was really really critical for the thing to pass.

In 14 years of policymaking I encountered this word “stupid” and this attitude many times. I am certainly not arguing that all Democrats or all progressives think like this. I hope it’s only a tiny fraction. In my experience it’s a mindset that reveals itself every once in a while from a small but influential set of progressive policymakers and outsiders who participate in and comment on the policy process.

At the same time, the progressive idea of “stupid Americans justify paternalism” is a composite concept. Let’s try to unpack that composite. Here are six variants I have seen expressed by some of my policymaking counterparts who reside on the far left of the spectrum.

- “The American voter is stupid because he is less well educated or less credentialed than I am.” This one is self-explanatory, a combination of arrogance + entitlement. Educational credentials are of course highly imperfect measures of intelligence. False positive and false negative errors abound. This variant is sometimes combined with a regional component, a coastal big city elitism embodied in snarky terms like “fly-over country” and bias against those with rural upbringings or southern accents.

- “The American voter is stupid because she ignores scientific evidence by opposing progressive policy X.” Popular discussion of this variant often begins with the progressive habit of seeing scientific ignorance only on the right, ignoring parallel problems on the left from those who reject scientific consensus on, among other issues, the safety of vaccines and of genetically-modified food and the environmental safety of fracking. While the issues and causes differ, scientific ignorance exists across the full range of the policy and political spectrum. A deeper flaw occurs when some progressives reframe a value difference as a rejection of a scientific conclusion. I can accept certain widely held scientific conclusions about greenhouse gas emissions and still believe that a particular cap-and-trade proposal is bad policy. This doesn’t make me anti-science or stupid, it just means that my values lead to a different view on what is good policy.

- “The American voter is stupid because he doesn’t know what’s in his own best interest. I, the progressive policymaker, therefore must enact a policy that will give me the power to make decisions for him.” This logic underlies many paternalistic expansions of government–benefit mandates in ObamaCare, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, outlawing Super Big Gulps in New York City. Sometimes using behavioral economics as intellectual cover, this logic creates a slippery slope whereby progressives start imposing policies that represent not just what they think is best for us stupid people, but what they think is best for us even when we might disagree if fully informed. The policy question is not whether people make stupid decisions every day. Many do. The policy questions are whether substituting a centralized, bureaucratic, and politicized authority subject to interest group pressure will result in fewer mistakes than we would make on our own, and whether we value the freedom to control our own lives, even when that freedom will lead us to make mistakes. I am for letting the American people make their own mistakes.

- “The American voter is stupid because, if he had the same information and understanding of the situation as I do, he would support less redistribution of society’s resources than I would.” This, of course, is not stupidity, it’s simply a different value choice. And it provokes a hard question for honest, well-intentioned and ethical progressives who believe in democracy: Are you willing to tell the truth to, honestly inform, and then accept the will of the American people, as expressed though our highly imperfect representative democracy, if it results in less redistribution than you would prefer? Which is more important to you: democracy or redistribution? Are American voters stupid if they don’t want quite as much redistribution as you?

- “The American voter is stupid because she was unable to see through my efforts to obfuscate the true redistributive effects of my policies.” It’s not just the malevolence behind this view that frustrates me. It’s the arrogance. Dr. Gruber may be the only one to have admitted to this line of thinking, but he is far from the only policymaker to use it.

- “The American voter is stupid for trusting that I believe in democracy, that I will use the policy power I am granted only to enact policies that reflect broad American values when they differ from my own.” This is why Dr. Gruber and those who think like him should not be trusted with power. It is especially true for those who hold power but were not elected by a popular vote: staff, appointed officials, and outside advisors. It is also an argument for smaller government. The greater the reach of government into our lives, the more tools and opportunities exist for those who cannot be trusted with power to abuse it.

If American voters are stupid because they think academic credentials do not perfectly equate with intelligence…

If they are stupid because they think policy decisions should be informed both by sound science and values…

If they are stupid because they would rather let people make their own mistakes than allow government to make different mistakes for them…

If they are stupid because they support less redistribution than certain progressive policymakers and their allies in academia…

If they are stupid because they don’t spend all their time trying to sift through policies intentionally designed to deceive them…

If they are stupid because they trust that elected and especially appointed American officials will not abuse the power temporarily granted to them…

… then I’m with stupid.

(photo credit: Andres Musta)