The President’s recess appointment of Dr. Donald Berwick

Today the President is recess appointing Dr. Donald Berwick to serve as Administrator of CMS, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS is responsible for administering more than $740 B of spending each year and will be key to implementing the new health care laws. This is a very important job.

Dr. Berwick runs a foundation, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus and Senator Grassley have for some time been asking Dr. Berwick to disclose the list of donors to his foundation. In the eleven weeks since he was nominated he has not yet done so.

Recess appointments are not quite routine, but they are Constitutional and are an ugly reality of how things sometimes work in Washington. Yet the timing and manner of Dr. Berwick’s recess appointment are clear process fouls by the Obama Administration. In this case the President is using the recess appointment power not to work around a filibuster as claimed, but to avoid disclosing information that is potentially relevant to Dr. Berwick’s service, to avoid an unpleasant reprise of the health care debate, and because it’s convenient for the Administration.

In a recess appointment the President bypasses the normal Senate confirmation process and appoints someone to a position within the Executive Branch. The President can do this only when the Senate is in recess – that is, not in session. The person appointed can serve until the end of the next session of Congress. In Dr. Berwick’s case, this means he can serve as CMS Administrator through the end of 2011. Technically, the President could then again reappoint Dr. Berwick for 2012-2013, but Berwick would have to be unpaid for that second stint. I don’t know of a second unpaid second recess appointment ever happening.

The Senate confirmation process usually works like this:

- The President nominates you for a senior position in the Executive Branch that is Senate-confirmed. In the Executive Branch this is called a PAS slot, short for Presidential Appointment, Senate confirmed.

- The staff of the Senate committee of jurisdiction (in Dr. Berwick’s case, the Senate Finance Committee) interview you. You have to disclose your finances, taxes, and fill out a bunch of questionnaires. This process can be both laborious and grueling.

- The Committee then holds a nomination hearing at which you testify and answer questions. The timing of the hearing is determined by the committee chairman (in this case, Senator Baucus).

- If you don’t foul up too badly at your hearing, sometime later the Committee members vote on your nomination. Again, the time of the vote is determined by the committee chairman. In most cases a majority of the committee will vote to report your nomination favorably to the full Senate.

- Your nomination then automatically goes onto the Senate’s Executive Calendar.

- Sometime later, the Senate Majority Leader (Reid) moves to proceed to your nomination. Usually the motion to proceed is adopted without delay, and the Senate is then debating your nomination.

- If you’re controversial, the question of your nomination can be filibustered. The Leader would need 60 votes to invoke cloture to end the filibuster.

- If cloture is invoked or if your nomination is not filibustered, after some debate the Senate then votes on your nomination.

- If a majority of the Senate votes favorably, you have then been confirmed by the Senate.

- You are then sworn in by an Executive Branch official and can begin work.

A recess appointment usually occurs when a nomination is very important to the President and is supported by a majority of the Senate, an impassioned minority fiercely opposes the nominee, and the majority lacks 60 votes to invoke cloture to overcome the minority’s filibuster.

Typically the above process will play out up to the point where the majority leader tries to invoke cloture and is blocked by the minority. Sometimes he’ll make the minority block cloture more than once to test their cohesion.

Then, having followed the regular confirmation process but having been stymied by a determined Senate minority, the President will recess appoint the nominee. To do this the President must have a cooperative majority party, because the tradition is that the Senate has to recess for more than three days for the recess appointment to be valid. If Republicans were in the majority now, they would technically recess for only one or two days at a time to prevent recess appointments. Senate Democrats did this in 2007-2008 to President Bush. If Republicans retake the Senate majority next year I would expect them to do the same to President Obama.

In the past recess appointments have been used after an actual filibuster. In this case the President is using a recess appointment to avoid the threat of a potential filibuster. Doing so also allows the nominee to avoid answering an uncomfortable question about his foundation’s funding sources. It also allows the Administration to duck a reprise of the health care reform debate four months before Election Day.

The Berwick recess appointment is extraordinary because the confirmation process didn’t even begin and because Republicans cannot be held responsible for the delay. In the eleven weeks since the nomination Chairman Baucus never held a hearing on Dr. Berwick. While some Senate Republicans threatened a future filibuster, no Senate Republican has yet had an opportunity to delay or block the confirmation process so far.

No member of the Finance Committee had any opportunity to question Dr. Berwick on either his fitness as a nominee or on his policy views.

The Senate Finance Committee therefore never voted on the Berwick nomination. It was never placed on the Executive Calendar. Leader Reid never tried to call up the nomination, and never gave Senate Republicans the opportunity to debate, vote upon, or carry through on their threatened filibuster.

Team Obama blames Republicans for forcing the President to use a recess appointment. Here’s White House Communications Director Dan Pfeiffer:

In April, President Obama nominated Dr. Donald Berwick to serve as Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Many Republicans in Congress have made it clear in recent weeks that they were going to stall the nomination as long as they could, solely to score political points.

But with the agency facing new responsibilities to protect seniors’ care under the Affordable Care Act, there’s no time to waste with Washington game-playing. That’s why tomorrow the President will use a recess appointment to put Dr. Berwick at the agency’s helm and provide strong leadership for the Medicare program without delay.

This would be a valid argument if Senate Republicans had actually filibustered the nomination, rather than merely threatening to filibuster it. Mr. Pfeiffer’s argument is not a reason for a recess appointment, it’s a rationalization for bypassing the confirmation process.

Yes, everyone anticipated significant Republican resistance to the Berwick nomination. Yes, everyone anticipated that some Republicans would filibuster the nomination. But this entire process never had a chance to play out, and that is a crucial process foul on the part of the President.

In anticipation of some of the counterarguments, I’ll end with some Q&A.

Attack: Why do you oppose the Berwick confirmation? He’s well-qualified.

Response: I’m not arguing against his confirmation. I’m arguing that he should go through the confirmation process. If he is successfully filibustered, then the President can recess appoint him. I might oppose his nomination, or I might be OK with it. I need more information, which now I’ll never get. More importantly, many Senators are in the same position.

Attack: Everyone knows the Republicans will filibuster him. Why bother going through with that process? This is faster.

Response 1: All delay so far is not the fault of Senate Republicans.

Response 2: Whether or not his nomination is filibustered, the committee process should not be skipped. Nominees should have to answer the committee’s questions and appear at a confirmation hearing.

Response 3: It is impossible to know if such a filibuster would succeed. Filibuster threats are easy to make and occur all the time. Actual filibusters are a little harder.

Response 4: The Senate has a constitutional role in the confirmation of senior Executive Branch employees. This should be bypassed only in extraordinary cases, and not just because a few Senators told the press they would filibuster.

Attack: Health care reform is too important. We need Berwick in place now.

Response: Then you should have had him answer the committee’s question about his foundation’s funding sources, and you should have pressured the Democratic Committee Chairman to begin the confirmation process instead of waiting for 11+ weeks. All delays up to this point are because (a) the nominee refused to answer bipartisan questions from the Committee Chair and Ranking Member, and (b) Chairman Baucus refused to schedule a hearing.

Attack: If Republicans didn’t filibuster everything the President wouldn’t have to do this.

Response 1: Republicans don’t filibuster everything.

Response 2: Even when they do filibuster, it’s important to make them go through that process. Force them to explain why this nominee is so egregious that the Senate should not even vote up-or-down on the President’s nominee. That’s an unpleasant debate, but it’s better that it occur than not.

Response 3: Believe it or not, sometimes Senators change their minds after they have had an opportunity to question a nominee they previously opposed. Yes, even some Republicans.

Response 4: A process foul like this makes it easier for Senate Republican Leaders to argue to rank-and-file Senate Republicans that they are an aggrieved minority. Whether or not you believe this is a process foul, this argument strengthens the ability of Senate Republican leaders to mount future filibusters. This is an unintended consequence that may hurt some of President Obama’s future nominees.

(photo credit: striatic)

Partisan premises for the 2010 election

Here are a dozen premises that appear to be driving Republican and Democratic party strategies as we approach the 2010 election.

As with any generalization about a political party these are tremendous oversimplifications. I do not suggest that all Republicans or all Democrats agree with each premise. This is instead my best attempt to describe the overall strategic postures of the two parties as defined by their leaders. Like my post on fiscal stimulus camps, this is an attempt to frame and structure the discussion, not to resolve it.

I disagree with many of the Democratic premises but have tried to characterize them as fairly as I could. I would appreciate input, especially from insider Democrats on how Democrats in leadership roles are thinking.

All of these premises are about economic and domestic policy, and I think each is important to this election cycle. Are there other premises related to foreign policy, national security, or cultural issues that will be as important this November? It’s easy to think of partisan differences on foreign policy, trade, social issues, immigration, energy/climate, or Guantanamo. But to me none of these seem central to the partisan strategies this cycle. Maybe my perspective is skewed because I care most about economic policy.

I hope you find this framework useful.

Premise #1: Health Care

- R: Those who voted for health care reform will suffer in November.

- D: Health care reform will be a net plus for those who supported it. At a minimum it will help with base voters and will be a net wash for most vulnerable Ds.

Premise #2: Health Care Timing

- R: Health care will continue to be important in November.

- D: Health care will fade as an issue as enactment moves farther into the past. It won’t be a big deal on Election Day.

Premise #3: Economy

- R: Voters will reject the party in power because the absolute condition of the economy is weak.

- D: Voters will recognize that, while weak, the economy is improving, it’s because of our policies, and we inherited a very weak economy.

Premise #4: Stimulus

- R: The fiscal stimulus didn’t work. Democrats are now trying to throw good money after bad and breaking their promises to pay for their spending.

- D: The fiscal stimulus rescued the economy from a depression. We need to do more even if it increases the short-term deficit. After the election we’ll combine it with long-term deficit reduction.

Premise #5: Deficits vs. Spending

- R: We have a spending problem which Democrats make worse each day.

- D: We have a deficit problem. Health care reform reduced the deficit as a good first step. Tax increases on the rich and a bipartisan commission are next.

Premise #6: Taxes

- R: Democrats will raise your taxes. A lot.

- D: We will only raise taxes on rich people and those who deserve it, like Wall Street, Big Oil, and Health Insurers.

Premise #7: Size of government

- R: Government is too big and Democrats are making it even bigger.

- D: Republicans want anarchy and are opposing sensible new protections in financial reform, health insurance reform, and protecting the environment.

Premise #8: Big Government vs. Big Business

- R: Voters are rejecting the expansion of Big Government.

- D: Voters want more government protection from Big Business.

Premise #9: Right/Wrong Direction

- R: Democratic policies are moving America in the wrong direction.

- D: Democratic policies are the beginning of a long healing process after eight years of the Bush Administration.

Premise #10: Role of the Tea Party

- R: The Tea Party phenomenon represents an opportunity to recapture independents and disaffected Democrats we lost in 2008.

- D: The Tea Party is overblown. This is a traditional rally-the-base midterm election.

Premise #11: Rejecting Democrats vs. Rejecting Washington

- R: Voters are angry with the ruling party in Washington.

- D: Voters are angry with the Washington establishment. Voters are rejecting R incumbents too and would hate/oppose Rs just as much if they were in power.

Premise #12: Blame someone else

- R: Voters will hold the Democratic majority responsible for outcomes, even if those outcomes are largely out of their control (e.g., unemployment, BP spill).

- D: Voters will recognize that we’re trying to fix problems caused by others: President Bush, Wall Street speculators, evil Health Insurers and Big Oil. Blaming those villains redirects voter anger in support of us.

Are these fair representations of the strategic premises and messages of each party’s leadership?

If so, how do they affect the party strategies for the fall?

(photo credit: Steve Rhodes)

Fiscal stimulus camps

I am going to try to group the different fiscal stimulus arguments into camps:

- Rules over discretion — Stanford economist John Taylor argues that discretionary monetary and fiscal policy have been counterproductive. He argues that monetary policy should follow a rule (like the Taylor rule). He further argues that both the 2008 (Bush/Pelosi/Boehner) fiscal stimulus and the 2009 (Obama/Pelosi/Reid) fiscal stimulus were ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst.

- Yes on monetary discretion, no on fiscal stimulus — Many conservatives like to complain about the Fed’s recent actions but would not advocate a wholesale change in how we approach monetary policy. They are basically OK with the Fed Chair and the Federal Open Market Committee using their best judgment, although they wish the recent financial crisis didn’t necessitate such aggressive use of that judgment. Members of this camp argue against all forms of fiscal stimulus. They think the 2008 and 2009 fiscal stimulus laws were both mistakes. Their arguments fall into three categories: (a) fiscal stimulus doesn’t work; (b) even if in theory it could work, it’s almost impossible in a real world of legislation to get the timing right; and (c) the deficit increase isn’t worth the possible short-term growth benefit. Membership in this camp means you oppose both increasing spending and cutting taxes to accelerate short-term GDP growth. Most Congressional Republicans would tell you they are in this camp.

- It depends on the kind of fiscal stimulus (R) — OK with discretionary monetary policy, OK with tax cuts as short-term fiscal stimulus (but would prefer permanent tax cuts offset by spending cuts), but opposed to increased government spending as short-term fiscal stimulus. This is where President Bush was in 2008, leading to the 2008 stimulus law. I think Greg Mankiw falls here in his article on fiscal stimulus, “Crisis Economics” in the excellent policy journal National Affairs.

- For two-sided fiscal stimulus — This was the President’s logic behind the February 2009 stimulus, which increased spending a lot and cut taxes a little. Team Obama mislabeled tens of billions of dollars of transfer payments as “tax cuts” but the bill did cut other taxes. In this camp you’re OK increasing the deficit for short-term spending increases and for short-term tax cuts if those policies will increase short-term economic growth.

- It depends on the kind of fiscal stimulus (D) — OK with discretionary monetary policy, OK with increased government spending as short-term stimulus, but opposed to cutting taxes even in the short run unless they are offset with other tax increases. This is where most of the Democratic Congressional Majority is at the moment.

- Fiscal stimulus works and we need a lot more of it through increased government spending — Dr. Krugman and Secretary Reich are here. Krugman is hammering the point repeatedly, and probably causing Team Obama heartburn by doing so.

- It’s different here in Europe — They aren’t opposed to fiscal stimulus in principle, but right now the Germans especially are far more concerned with deficits and debt than with short-term GDP growth.

The DC debate is a bit messy, but most of it lies between camps 2 and 5. Each camp has its challenges.

Camp 1, rules over discretion, is lonely and cannot practically achieve its primary goal. A noted economist like John Taylor can go toe-to-toe with Chairman Bernanke in a debate about the appropriate measure and use of a monetary policy rule, but most DC policymakers cannot. Membership in this camp requires you fundamentally disagree with how Chairman Greenspan made and Chairman Bernanke makes monetary policy decisions, and not just with the particular decisions they made. As a practical matter, a Member of Congress has next to zero ability to achieve John’s goal of rule-based monetary policy. The law establishes the Fed’s mandated goals of “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates?,” but gives the Fed Governors complete freedom on how best to pursue these goals. Also, while many conservatives cite John’s opposition to fiscal stimulus, it’s important to understand that his argument is primarily about monetary policy. If you favor discretionary monetary policy, you’re not in camp 1 even if you agree with Professor Taylor in opposing fiscal stimulus.

A lot of my DC Republican friends (especially in Congress) think they are in camp 2 opposing all fiscal stimulus, but I suspect they’d actually be in camp 3 if pressed. Over the past 18 months “fiscal stimulus” has been redefined to mean “the failed Obama/Pelosi/Reid stimulus,” and in a political context the easiest message for a Republican elected official is “The stimulus failed and I oppose more fiscal stimulus. In fact, I oppose all fiscal stimulus.” But 169 of 199 House Republicans voted for the tax-cuts-only 2008 fiscal stimulus law, as did 33 out of 49 Senate Republicans. And almost all House and Senate Republicans joined President Bush in arguing for the short-term macro growth benefits of both the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts. The 2001 and 2003 laws were designed to have both short-term and long-term benefits, but we Republicans were not shy of using traditional short-term growth arguments in a weak economy to justify support for these tax cuts. When you’re in the Congressional minority with a Democratic President and “fiscal stimulus” = “increased government spending,” it is easy to oppose “fiscal stimulus.” If, however, Republicans were in the majority, had a Republican President, and faced 10% unemployment, wouldn’t they be advocating immediate tax relief to “get the economy going again?” Would they really be advocating no fiscal policy action from Congress were they in charge? If they couldn’t get permanent tax relief, wouldn’t they again compromise and pass temporary tax relief? I think for many Congressional Republicans aversion to the Democratic majority’s proposed spending increases is shaping their stated positions on broader questions of fiscal stimulus. Republican Presidential hopefuls, in particular, may want to think twice before making definitive statements opposing fiscal stimulus as a general policy tool. They may need that tool someday.

I’m in camp 3, OK with cutting taxes to accelerate short-term economic growth. I feel a responsibility to say what I’m for and not just what I’m against. Rather than just complaining about where we are or proposing to repeal the Feb 09 stimulus and reduce the deficit, I would instead support converting all the remaining spending in that law into immediate and temporary tax relief to individuals. This would accelerate but not increase the budget deficit relative to where it is projected to be, and would result in front-loading whatever growth benefit we’ll get from those deficit increases. I would prefer permanent tax relief to temporary, combined with aggressive medium- and long-term spending reductions. Most Democrats and many economists (including CBO) would argue my short-term conversion policy would sacrifice growth because much of the tax relief would be saved rather than spent. I have two responses: (a) the debate about spending vs. tax multipliers is wide open, as Greg Mankiw points out in his article; and (b) even if much of it is saved, as a long-run matter, I’d rather have individuals save these funds than Congress allocate them for slow-spending pork projects. The downside of camp 3 is that few elected Republicans will admit they’re in it so I’m mostly alone. Also, with Democratic Congressional majorities my preferred policy won’t happen.

Camp 4, for two-sided fiscal stimulus, is where the President began 2009. Team Obama (i) missed the baseline forecast, (ii) let a Democratic Congress turn their proposal into an unfocused spending spree, and (iii) repeatedly botched the post-enactment communications, undermining their credibility. The February 2009 stimulus might have accelerated GDP growth, but we’ll never know, and even if it did nobody will believe it. It’s also interesting to see the President and a Democratic Congress shift into Camp 5, where it’s OK to spend money without offsets, but not to cut taxes.

Camp 5, supporting spending increases but not tax cuts as stimulus is what Congress just tried and failed to do with the “extenders” bill. While I think many of my DC Republican friends are fooling themselves into thinking they oppose all fiscal stimulus, I think many DC Democrats are using a fiscal stimulus argument to justify avoiding making hard choices on spending. How can you claim a bill that increases the deficit by only $30 B is “fiscal stimulus?” It’s way too small to move the needle on a $14 trillion economy. If you believe that fiscal stimulus can increase short-term GDP growth, and if you believe we need to do more, then you belong in camp 5 with Dr. Krugman and Secretary Reich and should be advocating short-term deficit increases measured in the hundreds of billions. Instead we see a Congressional majority that is trying to mitigate the effects of a recession by funneling money to sympathetic constituencies, refusing to offset the resulting deficit increases, and rationalizing this by labeling it as fiscal stimulus. At the same time, they plan to allow a huge deficit-reducing contractionary tax increase to take effect January 1.

Members of camp 5 must simultaneously argue:

- The last stimulus worked but I support doing even more;

- I support doing a little more, but not too much more, even while the unemployment rate is higher than when we first began; and

- More stimulative government spending that increases the deficit is good, while contractionary tax increases that reduce the deficit are also good.

Camp 6, the “Third Depression” camp, is intellectually consistent but also quite lonely, because if you’re an elected official it puts you on the wrong side of popular concerns about the budget deficit. There’s an easy way for Dr. Krugman, Secretary Reich, and other outsiders to resolve this — they could fortify their advocacy for larger short-term deficit increases by specifying the particular policies they propose for medium-term and long-term deficit reduction. But since those specifics mean immediate political pain for he who proposes them, Democratic elected officials (including the President) are unlikely to venture here before the election.

Most people in Camp 7 are busy watching the World Cup.

Once again I recommend Greg’s article for a clear explanation of the economic debate. If you want a quick global perspective, Robert Samuelson’s column is also excellent.

Dawn of the Dead: the Krugman remake

On his blog Dr. Krugman attacks Fiscal Commission co-chair Alan Simpson for his recent Social Security comments. More interesting than Dr. Krugman’s latest Social Security argument is that he is trying to kill the President’s Fiscal Commission by declaring it to be already dead:

But the commission is already dead … and zombies did it.

… So what does it mean that the co-chair of the commission is resurrecting this zombie lie? It means that at even the most basic level of discussion, either (a) he isn’t willing to deal in good faith or (b) the zombies have eaten his brain. And in either case, there’s no point going on with this farce.

I will respond to the specific “zombie lie” claim another day. Today I want to focus on the strategic problem Dr. Krugman’s post raises for the President.

The Commission has always been a long shot for the President. In the short run it provides him with a plausible-sounding answer to deficit questions in this mid-term election year as he urges Congress to increase spending, both as more short-term fiscal stimulus and to promote his domestic policy agenda.

In the 1-6 year timeframe, the President may believe that a bipartisan commission is the path with the best chance of brokering a bipartisan deal on the hard long-term fiscal policy decisions. Assuming good intentions, he may hope that he can then build upon a fledgling bipartisan agreement to create a legislative coalition that can succeed.

He may also think that a commission might fail because of opposition from the anti-tax Right. If it does, this would provide the President and his allies with an excuse to duck the hard long-term fiscal issues in the remainder of a first term: “I tried, but radical Republicans refused to compromise. What can I do?”

If Dr. Krugman turns this blog post into an ongoing drumbeat he can foul up that Presidential exit strategy in case the commission fails. If the Left attacks and kills the Commission’s chances for success, then Team Obama’s blame-Republicans-for-failure backup plan won’t work.

There is therefore a big difference between Dr. Krugman attacking Sen. Simpson for his substantive comments and Dr. Krugman declaring the commission dead. The first can be seen as vigorous/aggressive policy debate and may or may not be consistent with the President’s substantive views. The second is a threat to the President’s fiscal strategy.

To his credit, the President and his team have refused to take policy options off the table for the commission, even spending cut options which they might prefer not be a part of any solution. Now Team Obama needs to push back hard on anyone who tries to kill the Commission by asserting that it’s already dead.

Dr. Krugman is brazenly attempting to claim this authority. Without pushback from the President or his team, Dr. Krugman’s argument could quickly become a standard talking point for the Left.

I think the commission was structured unfairly. I fear the commission will produce recommendations that I oppose. I anticipate I will disagree as vigorously with the views of some commissioners as does Dr. Krugman with Sen. Simpson’s comments. I am skeptical the commission will succeed. At the same time, there is no other semi-plausible path to explore long-term fiscal solutions. I therefore hope the fiscal commission will have a chance to produce bipartisan recommendations and I think it is irresponsible for anyone to try to kill it before it does.

(photo credit: Armless Zombies? by Felxi42 contra la censura)

PolitiFact rates WH COS Rahm Emanuel’s statement False.

PolitiFact.com looked into White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel’s claim that President Bush gave the U.S. auto manufacturers a blank check, and at my response.

PolitiFact examined this key quote from the Chief of Staff:

In the case of General Motors, the prior administration wrote a check without asking for any conditions of change.

PolitiFact rated the White House Chief of Staff’s statement false and shows this “Truth-O-Meter.”

Here is PolitiFact’s concluding paragraph:

Emanuel’s statement — “In the case of General Motors, the (Bush) administration wrote a check without asking for any conditions of change” — implies that the Obama administration was tough while the Bush administration just threw money at the problem. Actually, the Bush administration detailed a number of conditions for change at General Motors, and Obama’s administration could have recalled the loans soon after taking office if officials felt the auto companies were not compliant. The Treasury Department documents and press reports contradict Emanuel’s claim, so we rate his statement False.

PolitiFact won a Pulitzer Prize in 2008 for their coverage of the 2008 election. ABC News relies on PolitiFact for fact-checking.

I hope someone from the White House press corps follows up.

“Emergency” does not mean “important”

In the latest iteration of the Senate extenders bill, an amendment by Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus, $58 B of spending is designated as an emergency. This is for two types of spending: (1) unemployment benefits, and (2) aid to States, mostly through the federal government paying a higher share of Medicaid spending.

Emergency spending is advantaged in the Congressional budget process.

- The total amount of discretionary spending, implemented through annual appropriations bills, is capped by the annual budget resolution. Discretionary spending designated as emergency spending does not count toward these caps.

- Mandatory spending, most of which is for entitlement programs, is on autopilot. Congressional budget rules require you to offset any legislative increase you propose in mandatory spending. An emergency designation waives this requirement. The same is true for tax cuts designated as emergencies.

There are other technical aspects of the emergency designation, but these are the most important. This year it’s a little hinky because there is and apparently will not be a budget resolution. The unemployment and Medicaid spending in the Baucus amendment are mandatory spending provisions.

OK, now that we know how emergency spending is advantaged, what is it? It turns out there is no formally binding definition in the legislative process, so as a formal matter, it’s whatever you can get away with labeling as an emergency. A Member of Congress can argue that X is not an “emergency,” and if he or she can get the votes to strike that emergency designation from the bill, then that spending will count toward the caps (discretionary) or its deficit effect must be offset (mandatory). If, however, a majority of Members (separately in the House and Senate) agree that they’ll label X as an emergency, then there is no procedural challenge available.

This formal procedural ambiguity can be dangerous in the hands of a Congress that doesn’t want to make hard choices. Sure it may be hard to argue that X is an emergency, but it’s probably easier than finding spending cuts to offset X, spending cuts which will involve real pain for some constituency that will complain loudly.

In the political debate, “emergency” has been distorted to mean “important and deserving of empathy.” This is an abuse. Emergency is not the same as important, and of course importance is in the eye of the beholder.

There is a definition first created in 1991 by the Bush (41) Office of Management and Budget. It’s a five-part test for whether a particular spending provision should be designated as an emergency. This is an AND test, meaning a provision must meet all five criteria to earn an emergency designation.

According to this 1991 definition, to qualify as emergency spending, the provision must be:

- necessary; (essential or vital, not merely useful or beneficial)

- sudden; (coming into being quickly, not building up over time)

- urgent; (requiring immediate action)

- unforeseen; and

- not permanent.

This definition was included in Congressional budget resolutions during the Bush (43) Administration. President Bush proposed codifying it in law.

Let’s compare increased a hypothetical request for more money for the Coast Guard to clean up the Gulf Spill with the proposed extension in the stimulus of unemployment insurance benefits and with the proposed extension in the stimulus of federal aid to States through higher Medicaid reimbursements. I will be overly generous and grant a yes where I think a plausible case can be made, even if I might disagree with that case.

| hypothetical request:Coast Guard / Gulf spill | Unemployment insurance extension | Medicaid FMAP extension | |

| necessary | yes | yes | yes |

| sudden | yes | no | no |

| urgent | yes | yes | yes |

| unforeseen | yes | no | no |

| not permanent | yes | ? | ? |

| emergency (all 5 yes) | yes | no | no |

The clear failures for unemployment and Medicaid are the “sudden” and “unforeseen” tests. Certainly now, 16 months after the initial enactment of these provisions, no one can plausibly argue that an extension is either sudden or unforeseen.

Both parties have violated this definition, which I emphasize is not now formally binding. Emergency spending designations have become an enormous loophole subject to increasing abuse by those who want to spend money without making hard choices. In the pending extenders bill, emergency designations are being used to exempt $57.8 B of spending from budgetary offset requirements.

Recommendations

- Congress should remove the emergency designations from the unemployment insurance benefit extension and the Medicaid FMAP extension.

- If Congress thinks that extending unemployment benefits and Medicaid aid to States are essential policies, they should prioritize and either cut other spending (my preference) or raise taxes.

- Congress should formalize the 1991 definition of emergencies, ideally in statute but at least in the Congressional Budget Resolution, if they ever do a budget resolution.

- In formalizing that definition, Congress should change its rules so that an emergency designation applies only if the Chairman of the relevant Budget Committee enters a statement into the Congressional Record explaining how the spending or tax provision meets all five elements of the definition. This would place a slight check on Congressional spenders who abuse the designation.

- In the Senate, a Member should be allowed to raise a point of order against an emergency designation, requiring 3/5 of the Senate to waive. Update: This already exists. I mistakenly thought it had expired.

(photo credit: Emergency Off by Gilbert R.)

Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel’s auto breakdown

This morning on ABC’s This Week, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel told Jake Tapper:

In the case of General Motors, the prior administration wrote a check without asking for any conditions of change. We said: Without a check from the American people, get yourself right. You’ve got to make fundamental change. They’ve made changes and now, as you know, General Motors is going to have an IPO. And most importantly, they’re going to keep open factories that they were planning on closing. So we’re righting an industry that was not doing itself, or the American people or its workers, the right thing. So it was a way of getting them to do the changes that they had postponed.

Mr. Emanuel’s claim that the Bush Administration “wrote a check without asking for any conditions of change” is provably incorrect. The Bush-era loans were conditioned on restructuring to become financially viable, with a precise definition of viability, specific restructuring goals, and quantitative targets.

Almost exactly a year ago I responded to a similar claim made by Council of Economic Advisers Member Austan Goolsbee. Here is an excerpt from that post:

<

blockquote>In the last few days of December

According to the terms of the loan (see pages 5-6 of the GM term sheet), by February 17th GM and Chrysler would have to submit restructuring plans to the President’s designee (and they did).

Each plan had to “achieve and sustain the long-term viability, international competitiveness and energy efficiency of the Company and its subsidiaries.” Each plan also had to “include specific actions intended” to achieve five goals. These goals came from the legislation we [the Bush team] negotiated with Frank, Pelosi, and Dodd:

- repay the loan and any other government financing;

- comply with fuel efficiency and emissions requirements and commence domestic manufacturing of advanced technology vehicles;

- become viable: achieve a positive net present value, using reasonable assumptions and taking into account all existing and projected future costs, including repayment of the Loan Amount and any other financing extended by the Government;

- rationalize costs, capitalization, and capacity with respect to the manufacturing workforce, suppliers and dealerships; and

- have a product mix and cost structure that is competitive in the U.S.

The Bush-era loans also set non-binding targets for the companies. There was no penalty if the companies developing plans missed these targets, but if they did, they had to explain why they thought they could still be viable. We took the targets from Senator Corker’s floor amendment earlier in the month [of December]:

- reduce your outstanding unsecured public debt by at least 2/3 through conversion into equity;

- reduce total compensation paid to U.S. workers so that by 12/31/09 the average per hour per person amount is competitive with workers in the transplant factories;

- eliminate the jobs bank;

- develop work rules that are competitive with the transplants by 12/31/09; and

- convert at least half of GM’s obliged payments to the VEBA to equity.

If, by March 31, the firm did not have a viability plan approved by the President’s designee, then the loan would be automatically called. Presumably the firm would then run out of cash within a few weeks and would enter a Chapter 11 process. We gave the President’s designee the authority to extend this process for 30 days.

I don’t see how the Chief of Staff can make the claim that he made to Mr. Tapper. The specific loan conditions are listed on pages 5 and 6 of this document.

In addition, the Obama Transition Team rejected (quiet) overtures made by the Bush Team to work with them to ensure a smooth handoff of the auto issue. For the full story of the auto loans, please see my post from June, 2009. Here are the summary points from that post:

- The Obama team declined to respond to the Bush team’s offer to work together to create a joint process that would have resulted in a resolution by March 1st or April 1st, rather than by June 1st for Chrysler and maybe September 1st for GM.

- We then worked with the Democratic majority to enact legislation that would have limited funds to be available only to firms that would become viable.

- After Congress left town for the holidays without having addressed the issue, President Bush was faced with a choice between providing loans and allowing these firms to liquidate in early January, which would have further exacerbated the economic situation for the incoming President. President Bush chose to provide the loans.

- We provided GM and Chrysler with sufficient funds to get to March 31st, not January 20th, and in those loans we gave the incoming Administration the ability to extend them for 30 more days.

- The loans were conditioned on restructuring to become viable, with a precise definition of viability, specific restructuring goals, and quantitative targets.

- The Obama Administration followed the restructuring process laid out in the Bush-era loans. They are now measuring that deal against the targets established in the Bush-era loans. The only changes the Obama team made were that they extended GM for 60 days rather than 30, and the Obama Administration directly inserted themselves into the negotiations as the pre-packager.

I hope someone from the White House press corps follows up on this. I have a feeling we will be hearing this claim frequently over the next few months.

(photo credit: cropped from an ABC News image)

How to waive the Jones Act

Jones Act waivers are in the news because of the Gulf oil spill. I would like to contribute to that discussion by sharing my experiences coordinating the Jones Act waivers for President Bush in the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. In 2005 I served as the Deputy at the White House National Economic Council.

I’ll begin with a quick definition.

cabotage (n): navigation or trade along the coast

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, aka the Jones Act, precludes a foreign-flagged ship from operating near the U.S. coast. As I understand it, outside of three miles it’s fine. I am most used to it in the context of it precluding foreign-flagged ships from transporting stuff from one U.S. port to another.

The Jones Act can be waived “in the interest of national defense.” Since the Coast Guard is part of the Department of Homeland Security, the Secretary of Homeland Security actually issues the waiver. The law says the Secretary shall waive it “upon the request of the Secretary of Defense to the extent deemed necessary in the interest of national defense by the Secretary of Defense.” The Secretary may waive it “either upon his own initiative or upon the written recommendation of the head of any other Government agency, whenever he deems that such action is necessary in the interest of national defense.”

Obviously this means that to waive the Jones Act now, the Obama Administration would have to make an argument that doing so was in in the interest of national defense.

Waivers can be granted on a case-by-case basis or a blanket waiver can be granted. The blanket waivers we did in 2005 were limited to particular purposes and for a fairly short timeframe.

I cannot speak to the particular needs in the current situation, but I imagine the most pressing need might be for oil skimmers that could operate near Gulf state coastlines.

Update: Commenter Scott points out that another section of law (45 U.S.C. 55113) specifically covers oil spill cleanup. Here is the text:

§55113. Use of foreign documented oil spill response vessels

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, an oil spill response vessel documented under the laws of a foreign country may operate in waters of the United States on an emergency and temporary basis, for the purpose of recovering, transporting, and unloading in a United States port oil discharged as a result of an oil spill in or near those waters, if

(1) an adequate number and type of oil spill response vessels documented under the laws of the United States cannot be engaged to recover oil from an oil spill in or near those waters in a timely manner, as determined by the Federal On-Scene Coordinator for a discharge or threat of a discharge of oil; and

(2) the foreign country has by its laws accorded to vessels of the United States the same privileges accorded to vessels of the foreign country under this section.

It would seem that (1) involves an easier test than the national security test in the Jones Act. I don’t know, however, whether (2) binds in any particular cases. Do other countries that have oil spill cleanup equipment that could be used have similar provisions in their law? If so, then this would seem to be an easy way to get their equipment here. If not, then this section of law doesn’t help us.

Note also that if the two conditions are met, this overrules the relevant sections of the Jones Act, because of the language “Notwithstanding any other provision of law.”

In case it’s helpful, here’s what we did in 2005.

Round 1 – Katrina

- August 29, 2005 – Landfall of Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana.

- September 1, 2005 – President Bush announces that his Administration is waiving the Jones Act temporarily “for the transportation of petroleum and refined petroleum products.” This was an 18-day waiver.

- Here is the text of the waiver by Secretary Chertoff. You can see that he justified it in terms of national security, and did so “in consultation with and upon the recommendation of the Secretary of Energy.”

- The waiver covered gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and “other refined products.” He also waived it “for the transportation of petroleum released from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve.”

- This waiver allowed foreign-flagged short haul ships to transport these liquids between ports on the Gulf Coast, and (I think) even from Louisiana and Texas to the Eastern Seaboard. The pipelines that normally supply fuel to the entire Southeastern U.S. were without power, and we were concerned about fuel supply shortages. The waiver did not increase the total amount of fuel within the U.S., but it provided flexibility for that fuel to move as rapidly and efficiently as possibly to where it was most needed.

- September 19, 2005 – First waiver expires.

Round 2 – Rita

- September 24, 2005 – Landfall of Hurricane Rita.

- September 26, 2005 – At President Bush’s direction, Secretary Chertoff again waives the Jones Act with the same limitations as before. This waiver is for 30 days.

- October 25, 2005 – Second waiver expires, and we shift to case-by-case consideration of waiver requests.

I learned a few things from coordinating this process for President Bush.

- The direct benefits of a waiver were, in this case, small and diffuse. Waivers allowed 50K barrels per day here, and 100K barrels there, to arrive several days earlier than they would have otherwise. The waiver resulted in handfuls of short-term arrangements that moved fuel more expeditiously to where it was needed in the Southeastern United States.

- The fuel situation was so dire that every little bit helped. The direct benefits were small but still worth doing. We were in a situation where every little bit counted and was worth doing.

- Even more than the added shipping capacity, the waivers’ principal benefits were that they added speed and flexibility to the transportation of fuel.

- There was no short-term policy cost to the waivers. This made it an easy call for the President.

- If you’re a supporter of protecting U.S. shippers, shipbuilders, and maritime workers from foreign competition, then there is a long-term policy cost to a waiver. I think this cost was small, but I’m not in that industry. Those in the affected U.S. industries regarded these waivers as hugely important, and they lobbied the Administration hard.

- The pushback was not just from maritime unions, but also from the U.S.-flagged shipping industry, including shippers and shipbuilders, and including Rs and Ds on Capitol Hill who were close to the industry.

- Industry lobbied against the waivers. They lobbied for shorter timeframes and for narrower scopes. Once the waivers were granted, they pressured Customs and Border Patrol on enforcement.

- They lobbied at all levels, including trying to make their case to me. They were most effective pushing on the Cabinet and sub-Cabinet.

- Even some Cabinet officials in a Republican Administration were affected by the political pressure brought to bear by the industry.

- In both waivers, the President ultimately made the decision. I think it was an easy choice for him – he wanted to do everything possible to help solve the pressing short-term problems in the Gulf region. Long-term policy arguments from U.S. industries seeking protection from foreign competition were less important, and political pushback irrelevant.

Without a strong lean from President Bush on his Cabinet to “do everything we can,” the waivers would not have happened. Given the intense pushback from the narrow interest groups, Presidential leadership was required to make this happen. The benefits were small but, in my mind, easily worth it. When things are really bad in the Gulf, you do everything you possibly can, even if it’s small.

At the time the debate sounded like this:

- A: We have found N foreign-flagged ships that can help us get this done.

- B: We have American ships and crews you can use.

- A: Maybe, but the foreign-flagged ships are better/faster/more flexible/ready now.

- B: But we have American ships and crews you can use, and the marginal improvement in speed or flexibility is small.

- A: Sure it’s small, but every little bit helps.

The Deputy Administrator of the Maritime Administration (MARAD) has confirmed that one foreign-flagged skimmer has made a Jones Act waiver request. Yesterday, Dallas businessman Fred McAllister announced that “he has immediate access to 12 foreign ships and could pull in another 13 vessels in the next month.”

Before these recent developments I had frequently read and heard the Administration argue “We don’t have any requests.” This is reminiscent of the house on Halloween with no lights on and an angry pit bull tied to a tree in the front yard. When asked why they don’t hand out candy to trick-or-treaters, they reply that they haven’t had any requests.

In my experience government officials in crisis management sometimes focus too much on what the government will do, and not enough on the incentive effects of what the government says to the private sector. A blanket waiver combined with a strong encouraging signal from government officials could, I think, spur significant private help, including from friends around the world. We’ll never know unless the President tries.

Recommendation

- I recommend the President waive the Jones Act for all purposes related to the oil spill and oil spill cleanup. I recommend a 75-day waiver to take us through the end of August (when the relief well is supposed to be done?). I assume a 30-day waiver with the possibility of extension is more practically feasible.

- I recommend the President announce that he is directing Secretary Napolitano to issue the waiver, so that it is a Presidential decision. He would be signaling his willingness to do everything possible to help clean up the Gulf Spill, even if it ticks off certain domestic economic interests.

- I further recommend the President have his press secretary announce, at the podium, that the United States has waived the Jones Act, and that we are asking owners of foreign-flagged ships, wherever they might be in the world, to send those ships to the Gulf of Mexico to help clean up the spill. The State Department would reinforce this message through diplomatic channels.

Update: Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) is the Ranking Republican on the Senate Commerce Committee, which has jurisdiction over the Jones Act. Friday morning she introduced S. 3512, a bill to legislatively suspend the Jones Act for the Gulf spill cleanup. Here is the relevant text of the bill:

SEC. 2. WAIVERS.

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, section 12112 and chapter 551 of title 46, United States Code, shall not apply to any vessel documented under the laws of a foreign country while that vessel is engaged in containment, remediation, or associated activities in the Gulf of Mexico in connection with the mobile offshore drilling unit Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Kudos to Sen. Hutchison, as well as to Sen. Cornyn (R-TX) and Sen. LeMieux (R-FL) who have already cosponsored it. I hope that others do as well. I also hope Sen. Hutchison presses the point by forcing the Senate to either pass this bill, or for one of her colleagues to object to its passage and to explain why.

(photo credit: Leaking Oil Invades Louisiana Habitats, NASA/GSFC/LaRC/JPL, MISR Team)

Oil spill crisis as opportunity

Here is Rahm Emanuel’s famous quote, from November 19, 2008. You don’t need to watch more than the first minute.

The President’s Oval Office address last night suggests an implementation of this principle, as he tries to reconfigure the climate change / cap-and-trade debate into a new War on Fossil Fuels. It appears the President will attempt to use the oil spill crisis as an opportunity to enact cap-and-trade legislation which otherwise has almost no chance of becoming law.

In launching this war he is foregoing an opportunity for targeted legislation addressing only the risks of deepwater drilling. This alternative legislative path could give America and her President a quick, easy, bipartisan policy victory which I believe could rally and unify the nation when we sorely need it.

The War on Fossil Fuels

Let’s look at the words used by the President last night. We begin with his heavy use of military imagery:

… the battle we’re waging against an oil spill that is assaulting our shores and our citizens …

We will fight this spill …

I’d like to lay out for you what our battle plan is …

I’ve authorized the deployment of over 17,000 National Guard members along the coast. These servicemen and women …

I urge the governors in the affected states to activate these troops …

The same thing was said about our ability to produce enough planes and tanks in World War II.

We can see that fossil fuels are the enemy:

For decades, we’ve talked and talked about the need to end America’s century-long addiction to fossil fuels.

The transition away from fossil fuels is going to take some time …

… as long they seriously tackle our addiction to fossil fuels …

The use of “war” with “addiction to fossil fuels” suggests a closer communications parallel may be the “war on drugs.”

We can also see that climate change, cap-and-trade, global warming, and greenhouse gases are not the communications priority. The President referred once to “a strong and comprehensive energy and climate bill” passed by the House earlier this year. He did not say any of the other phrases, most notably not “cap-and-trade.” That language appears to be nearly dead. Then again, he did refer to “pricing carbon” one week ago.

Most importantly, the President defined the policy goal as “the need to end America’s century-long addiction to fossil fuels.” He reiterates this by saying,

So I’m happy to look at other ideas and approaches from either party – as long they seriously tackle our addiction to fossil fuels.

Q: How does the President reply if the minority party offers, ‘We will work with you in good faith on an answer to deepwater drilling safety, but will continue to disagree with you on broader questions of fossil fuels and specifically on cap-and-trade.” Does he take the partial win and solve the deepwater drilling problems? Or does he refuse and hold out for the rest of his energy/climate agenda?

One climate issue, two separable energy issues

If you are focused on carbon emissions, then oil, coal, and natural gas naturally group together as “fossil fuels” and are the combined source of the problem. If you are focused on energy, then oil is one issue (transportation), and coal and natural gas are another (electric power).

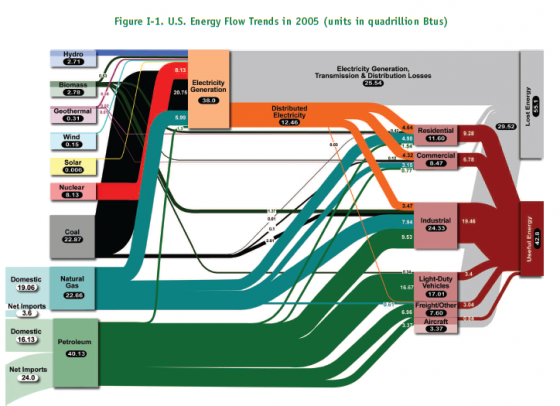

We use almost no oil to produce power in the U.S., and electricity powers only a tiny fraction of our transportation, despite recent increases in hybrid and natural gas vehicles. Yes, they’re growing at a rapid rate. But the overlap between oil as one type of energy source vs. coal and natural gas as another is vanishingly small. My favorite energy graph makes this clear. Look at the thin green lines that go from petroleum to supply residential and commercial power, and at the even thinner orange and turquoise lines that show how much our transportation is fueled by electric power and natural gas.

(Source: The University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and the Department of Energy)

Someday when battery technologies improve, the fuel and power worlds will blend in the U.S., and there will be strong and direct economic relationships between the production of electric power and the use of oil. Until that day, from an energy perspective, “fossil fuels” conflates oil with coal and natural gas in a way that is at best confusing and at worst misleading. Substituting biofuels for oil or making vehicles more fuel efficient has almost no effect on the amount of coal or natural gas we use. “Produc[ing] wind turbines,” “installing energy-efficient windows, and small businesses making solar panels” are quantitatively irrelevant to our use and production of oil. All the windmills and solar panels you could imagine will not reduce our dependence on oil as a transportation fuel.

The President’s gamble

The President risks overreaching by trying to use a crisis in one subset of domestic oil drilling to enact a policy agenda that applies to all types of oil drilling and imports, and to coal, and to natural gas. Were he to focus just on solving the deepwater drilling problem, he’d have a slam dunk. Instead he’s trying not to let this crisis go to waste, and to use it as an opportunity to enact indirectly related policies that are much more hotly disputed.

Two scenarios

Scenario 1 – Imagine that the President proposes new legislation targeted at the problem of engineering safety in deepwater drilling. Imagine his legislation contains five provisions:

- Require that all deepwater wells have a relief well in place before production begins.

- Mandate requirements for double piping and a list of other industry engineering best practices. The prior best practice for engineering safety becomes the legally mandated minimum.

- Mandate that each deepwater drilling operation be insured for at least $20 B of environmental damage before production can begin. Insurers will therefore require further engineering stringency to protect themselves.

- Raise the legal liability cap for any drilling platform to $50 B, just to be safe.

- All new wells must meet all of the above requirements, and all existing wells must cease production until they meet them. (The details here might need some work.)

With these requirements, some amount of deepwater drilling would cease because it wouldn’t be economical with the added costs. I’m confident that policymakers across the board would say, “Fine. If the added protection is not worth that extra cost, then don’t drill there. I want a belt, and suspenders, and Velcro too.”

I believe the legislation in scenario 1 would pass the House and Senate within a week or two, with overwhelming and possibly unanimous bipartisan majorities. The President could quickly unify the country and celebrate a wise bipartisan solution to preventing the recurrence of a painful problem. That would still leave the existing crisis, but the long-term policy issues would be solved.

Scenario 2 – The President pushes for enactment of cap-and-trade legislation which raises the cost of gasoline and diesel fuel, and of power produced from coal and natural gas. He insists that Congress include all the policies from scenario 1 in this bill.

Scenario 2 is a huge gamble. If the President succeeds, it will probably look like the health care fight. It will be a long, vigorous, largely partisan debate, overlaid with regional economic and energy interests. Legislation will become law only after squeaking out a 60th vote to overcome a filibuster.

The President knows he cannot enact cap-and-trade before November without a game changer. He assumes his legislative margin will be (much) smaller next year. He is rolling the dice to see if he can turn this crisis into a legislative opportunity, in what may be his last chance to enact a national carbon price.

My view

Sometimes it’s good to vigorously debate important policy issues. Sometimes America needs to make a huge directional change and only a strong President can lead us in a new direction. These directional shifts are painful for the country as we argue and fight, but if you agree with the new direction, that squabbling is worth it.

I think America is as deeply divided on climate change issues as it is on health care. I’d like us to change direction on energy, but I’m OK doing so gradually as technology allows us to do so without imposing enormous costs on our economy. This explains why I often support policies focused on energy technology research and development.

I think solving our deepwater drilling engineering safety problems is now a top national policy priority. I think our other top domestic policy priority needs to be near-term economic growth. I rank climate change lower on my list of policy problems.

The President could have a quick, clean, bipartisan win on legislation that would eliminate the risk of another spill like this one.

Instead he is rolling the dice again, gambling that he can leverage the problems with drilling for oil in deep water to get legislation that also raises costs for power production. He is also choosing a path that he knows will provoke partisan conflict. Maybe he sees an electoral benefit to having the fight.

I assume the President believes what he says, and he thinks that fossil fuels and the combined problems of environmental damage from deepwater drilling, the national security externalities and economic costs of our oil dependence, the pollution and climate change externalities from carbon emissions from all sources, all must be solved at once and immediately. He wants to change America’s direction sharply and suddenly, even if doing so is painful economically.

I respectfully disagree with sharply and suddenly, because the benefits are uncertain and the costs are significant. Also, the specific cap-and-trade bills being debated are a horrible mess of political bargaining and implementation nightmares.

The President’s War on Fossil Fuels will reinvigorate an intense policy debate on the future of energy and environmental policy in America. He may be successful in bending the Congress to his will, as he did with health care. He may fail.

I prefer another path that is simpler, faster, more unifying, and more targeted at the problem that is in the forefront of our consciousness this summer.

I think it would be good for America to unite and say, “We worked together to prevent that problem in the Gulf from happening again.” It is easy to do so, and I wish the President would choose that path instead.

(photo source: White House)

Dynamic Dr. Krugman

In his column today Dr. Paul Krugman argues that the deficit impact of a large ($1 trillion) stimulus would be mitigated by the effects of higher GDP growth:

Consider the long-run budget implications for the United States of spending $1 trillion on stimulus at a time when the economy is suffering from severe unemployment.

That sounds like a lot of money. But the US Treasury can currently issue long-term inflation-protected securities at an interest rate of 1.75%. So the long-term cost of servicing an extra trillion dollars of borrowing is $17.5 billion, or around 0.13 percent of GDP.

And bear in mind that additional stimulus would lead to at least a somewhat stronger economy, and hence higher revenues. Almost surely, the true budget cost of $1 trillion in stimulus would be less than one-tenth of one percent of GDP … not much cost to pay for generating jobs when they’re badly needed and avoiding disastrous cuts in government services.

Dr. Krugman focuses only on the long-term debt service costs of a large new stimulus. This assumes we keep the full trillion dollar cost of his hypothetical stimulus as public debt forever, and he argues the “true budget cost” is just the added burden of interest payments. I think looking at only the interest costs is an incomplete way to measure the true budget cost of a policy change, but today I want to focus on the bolded sentences and walk through Dr. Krugman’s logic.

Let’s grab an envelope and write on the back. Please note that this is not my “estimate for the Krugman stimulus.” I’m simply constructing a numeric example to demonstrate a concept. Except for the trillion dollar starting point, these are my numbers, not Dr. Krugman’s:

- Enact a stimulus law that increases the deficit by $1 trillion.

- Assume the stimulus law works and increases GDP growth. Even if you think fiscal stimulus is largely ineffective, please play along. Let’s be super generous and assume it’s all immediately effective and there’s no waste, so it adds four percentage points to GDP this year. I don’t think this is possible and I’m just picking four as a nice round number for this example.

- We expect to have a $15-ish trillion economy this year. ($14.7 T according to CBO.) That’s $15,000 B.

- +4% X $15,000 B = +$600 B higher GDP from our perfect magic $1 Trillion stimulus.

- Government takes on average about 18% of GDP in taxes. It’s lower during recessions but higher over the next decade under the President’s policy. Round up to 20%.

- 20% X $600 B = $120 B in higher revenues resulting from the higher GDP growth resulting from the perfect magic stimulus.

- $1,000 B gross deficit impact – $120 B higher revenues = $880 B net deficit impact of this hypothetical stimulus law, 12% less than the original gross score.

As a technical matter you can break this process up into two steps. The first step is where you guess how much your policy will increase GDP. The technical experts call this dynamic analysis. In the second step of dynamic scoring you translate the higher GDP estimate into an estimate of increased government revenues and therefore a smaller budget deficit.

Note the policy still increases the deficit, in this case by almost $900 B. This perfect magic spending stimulus does not “pay for itself” by a long shot. As Dr. Krugman points out, the dynamic aspects of it merely reduce the gross deficit increase: “additional stimulus would lead to a somewhat stronger economy, and hence higher revenues.”

You also need to think about the effects on interest rates, so a key assumption in the calculation is how the Fed will react. If you think the Fed will raise interest rates in reaction to your big fiscal policy change, then GDP growth will increase less rapidly and government debt service costs will increase, wiping out some of the dynamically scored benefit. The Fed’s reaction function probably depends on the strength of the economy – in a weaker economy the Fed won’t raise interest rates as much and so you get a bigger dynamic effect. If the economy were humming along at 5% unemployment rather than almost 10%, the Fed would worry about instantly adding four percent to GDP and would be more likely to raise interest rates, causing the dynamic benefit in the above example would be smaller.

As a practical matter you’d only want to dynamically score fiscal policy changes that are big enough to move the GDP needle in a measurable way. It would be silly to repeat the above back-of-the-envelope calculation for a $1 B law, because that’s way too small to measurably effect a $15 trillion economy. There’s some large de minimis threshold you would need to exceed for your estimate not to be silly.

Also, the policies within the law affect your estimate. The +4 percentage points I assumed depends on how much you think the policy will increase GDP, and how quickly. Economists love to debate these questions about the multiplier of certain types of spending increases vs. other types of tax cuts. My favorite paper is by Greg Mankiw and Matt Weinzierl: Dynamic Scoring: A Back-of-the-Envelope Guide. They write:

The feedback is surprisingly large: for standard parameter values, half of a capital tax cut is self-financing.

The (rounded and oversimplified) 20% number I used depends on what components of GDP will be increased, since different parts of the economy are taxed at different rates.

Dynamic scoring was originally advocated for tax cuts by conservatives who correctly argued that “static scoring”overestimated the deficit impact of large, broad-based tax cuts and incorrectly argued that the dynamic effect was so large that tax cuts would “pay for themselves.”

VP Cheney said this once and caught years of grief for it. He was incorrect – no conceivable tax cut from our current position can fully pay for itself. Using the logic described above, a broad-based reduction in rates on labor or capital income could, however, partially pay for itself.

In the world of DC fiscal policy combat, you will rarely hear a conservative admit that tax cuts do not fully pay for themselves, just as you will rarely hear a liberal acknowledge that large broad-based tax rate cuts do increase GDP growth and partially offset the gross deficit effect.

CBO began limited use of dynamic scoring (which they refer to as “relaxing the assumption of fixed nominal GDP”) in 1995 at the urging of Congressional Republicans.

While Dr. Krugman has long acknowledged the logic of dynamic scoring, it appears he supports it only for spending increases, and only when Democrats are in charge (seriously).

Here is Dr. Krugman in February 1995 (emphasis added by me):

But if you want to know whether we are really on the way to becoming a Latin American look-alike economy, the key issue to watch is a seemingly arcane one: the idea of “dynamic scoring” for tax cuts.

The basic idea of dynamic scoring is reasonable: People will alter their behavior when you change tax rates, so if you want to figure out how much revenue is gained or lost from these changes, you should take that altered behavior into account. For example, if you cut the federal gasoline tax, people might buy less-fuel-efficient cars, raising gas consumption, so the feds could conceivably end up with more rather than less revenue.

The problem is that economics is not (to say the least) an exact science, so that attempts to predict the effects of tax changes on behavior are both uncertain and controversial. Thus, the only kind of person you want to trust with dynamic scoring is someone who not only knows his stuff but will consistently bend over backwards to avoid reaching comfortable conclusions simply because they are politically convenient.

Do the Republican leaders and their economic advisers who are calling for dynamic scoring meet this test? Does the Republican majority believe that a cut in the capital gains tax will actually reduce the deficit because it has made an objective study of the statistical and economic issues involved, and has reached the conclusion in spite of a determination not to engage in wishful thinking?

…

So how should you approach the idea of dynamic scoring? With great caution. If the Republicans show a lot of enthusiasm for the idea, or if they choose a director for the Congressional Budget Office who loves the notion, then you might want to think about investing your money someplace where bitter experience has taught politicians and the public the virtues of responsibility–someplace like, say, Argentina.

Here he is in January 2003:

<

blockquote>Will this alcoholic

Now that Democrats are in charge, today Dr. Krugman titles his column “The Bad Logic of Fiscal Austerity” and argues for dynamic scoring of a trillion dollar stimulus. Given CBO’s projection of budget deficits exceeding four percent of GDP for the next ten years, it makes me wonder if Dr. Krugman thinks this quote from his 2003 column now applies:

It’s O.K. to run a deficit during a recession, as long as the deficit is clearly temporary. But both the numbers and the administration’s search for excuses tell us that there’s nothing temporary about the red ink. On the contrary, we’ll probably be on a deficit bender until the baby boomers retire – and then it will get much worse.

My view

- Dynamic scoring is conceptually valid.

- It should be applied to both the tax and spending sides of the ledger.

- When doing dynamic scoring you need to think hard about (1) the effect of the proposed policies on short-term economic growth, (2) how the Fed will react, and (3) whether the specific policies increase the capacity of the economy and the potential for higher long-term economic growth. You’ll probably have different parameters based on both the specific policy change and the short-term status of the economy.

- It’s hard to estimate the parameters, so dynamic scoring should be applied in very limited cases: only to very large, broad-based policies that will undoubtedly affect the level of GDP. I would probably set a threshold of a gross deficit effect of at least half a percent of GDP per year. That’s $75-ish B per year, or $750 B over ten years. Really big.

- While tax cuts do not fully pay for themselves, large broad-based cuts in tax rates on capital or labor income can partially pay for themselves.

- The deficit effect of a proposed policy should be one important factor in decision-making. I don’t need a tax cut to pay for itself to think it’s good policy if there are other reasons to do it. Others might argue the same for particular spending increases.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)