Comparing Obama economics to Clinton economics

Treasury Secretary Geithner speaks this afternoon at the liberal Center for American Progress. His staff have released two quotes to the press:

Secretary Geithner: Ultimately, fiscal policy is about getting the conditions right for economic growth, prosperity, and job creation. Over the past two decades, Washington ran an experiment on that front. In the 1990s, the government put an end to budget deficits, and America enjoyed a period of growth led by the private sector where prosperity was widely shared and job creation was robust. Over the next decade, Washington tried a new path, running up huge debts, while incomes for most Americans stagnated and job creation was anemic. We are living today with the damage that misguided policy caused.

So, as we look to a new decade, there’s some empirical evidence around what works and what doesn’t. Rather than creating a false prosperity fueled by debt and passing the bills on to the next generation, we need to restore America to a pro-growth tax and fiscal policy, where the middle class once again has a chance to prosper.

Secretary Geithner: Borrowing to finance tax cuts for the top two percent would be a $700 billion fiscal mistake. It’s not the prescription the economy needs right now, and the country can’t afford it.

It’s disappointing to see this from Secretary Geithner, whom I see as the least partisan member of the Obama economic team. Tradition suggests I should respond by engaging on the other side of the Secretary’s partisan comparison. This is not, however, a debate between two economic philosophies, but instead a debate among three: Clinton, Bush, and Obama. The Secretary makes an important mistake by suggesting that the Obama Administration is returning to the fiscal policies of the Clinton Administration.

In addition, Obama v. Bush debates are almost always colored by a heavy partisan tinge, so let’s see if we can learn anything by comparing Clinton to Obama on both fiscal policy and economic results.

Leaving out the Bush comparison, the Secretary’s logic follows three steps:

- the strong economic numbers during the Clinton Administration are a result of the fiscal policies of the Clinton Administration;

- the Obama policies are a return to the Clinton policies; and therefore

- the Obama policies will once again produce a strong economy like we saw in the 90s.

I disagree with (1) but today I want to focus on (2) and (3). I believe the following data will disprove both claims using the Obama Administration’s own numbers.

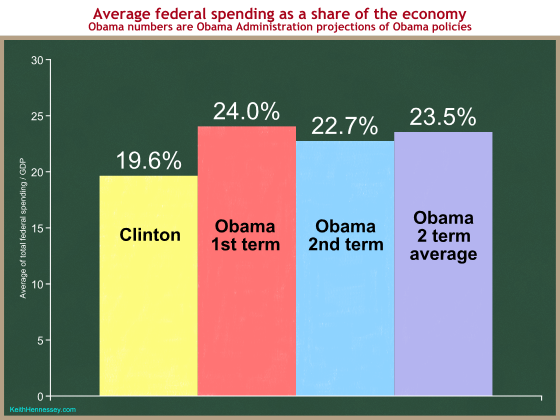

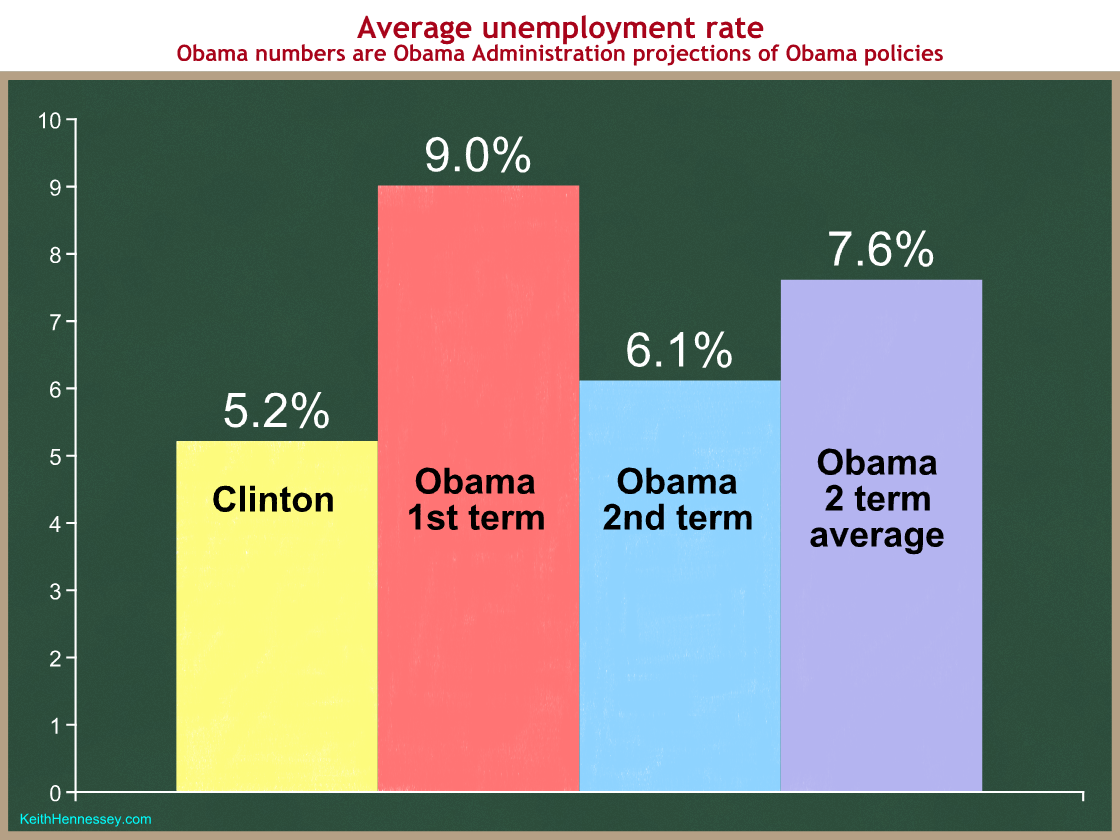

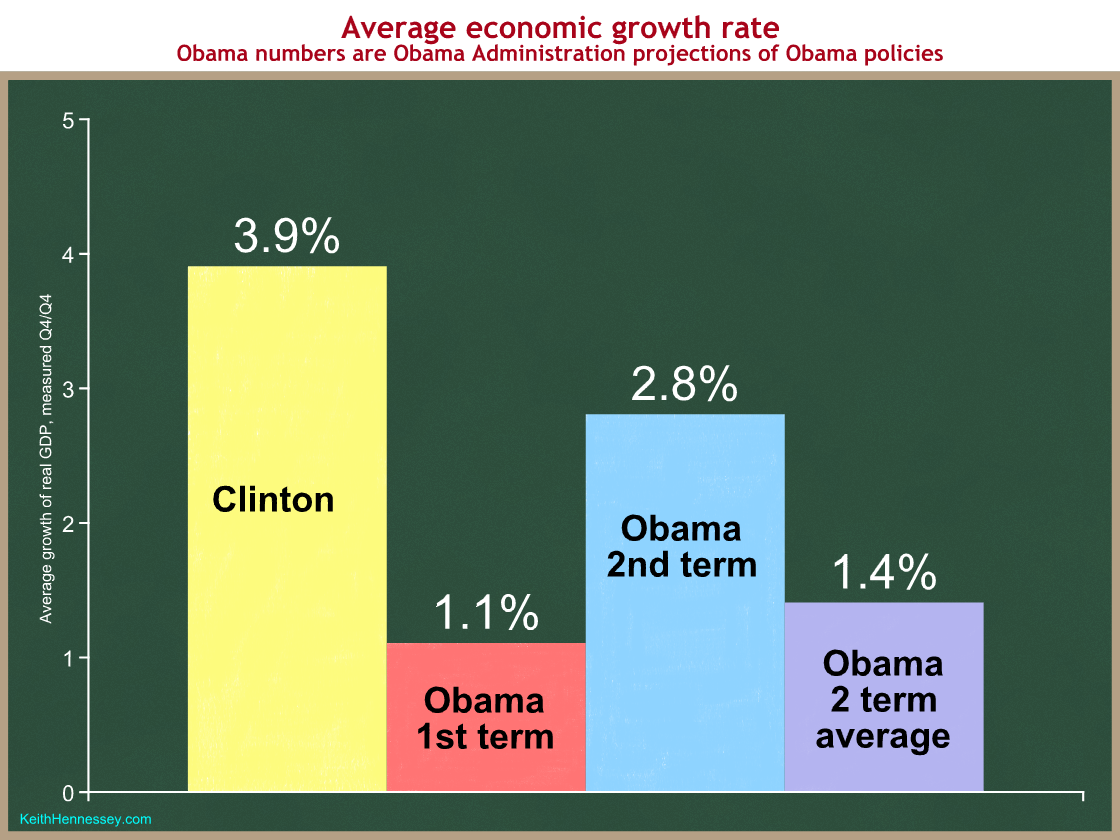

Here are the Clinton actuals vs. projections for the Obama tenure as projected by the Obama Administration.

| Clinton | Obama (projected by Team Obama) | |||

| 1st term | 2nd term | 2 terms | ||

| Unemployment rate | 5.2% | 9.0% | 6.1% | 7.6% |

| Average real GDP growth | 3.9% | 1.1% | 2.8% | 1.4% |

| Spending / GDP | 19.6% | 24.0% | 22.7% | 23.5% |

| Taxes / GDP | 19.2% | 16.1% | 18.9% | 17.4% |

| Deficit / GDP | 0.4% surplus | 7.8% | 3.9% | 6.0% |

| Spending / GDP (without interest pmts) | 16.9% | 22.3% | 19.9% | 21.2% |

| Deficit / GDP (without interest pmts) | 3.3% surplus | 6.2% | 1.0% | 3.8% |

| Top effective tax rate on a successful small business owner (federal) | 43.9% | 43.9% | 44.8% | n/a |

That’s a lot of numbers. Here are my data and sources. Since a two-term Presidency affects nine fiscal years rather than eight, that’s how I’m calculating the averages. For an explanation of this logic see this post. If you think my logic is bad, you can see the calculations for eight-year averages in my backup spreadsheet. You’ll see that the conclusions don’t change, and in most cases my preferred methodology actually makes President Obama’s numbers look slightly better.

Let’s turn these numbers into graphs, starting with the fiscal policies. Is President Obama proposing a return to the Clinton fiscal policies? Not on spending:

Team Obama projects that, if President Obama’s policies were implemented as he proposes them, average federal spending would be a dramatically larger share of the economy than it was under President Clinton.

Some will argue that President Obama’s average is unfairly high because he had to cope with a severe recession, while President Clinton faced a benign economic environment throughout his tenure. But spending in a hypothetical Obama second term, long past the financial crisis of 2008, would still be 16% higher as share of the economy than Clinton’s average. (22.7 -19.6) / 19.6 = 15.8%

Based on this graph I don’t see how Secretary Geithner can suggest that President Obama is returning to the fiscal policies of the 1990s.

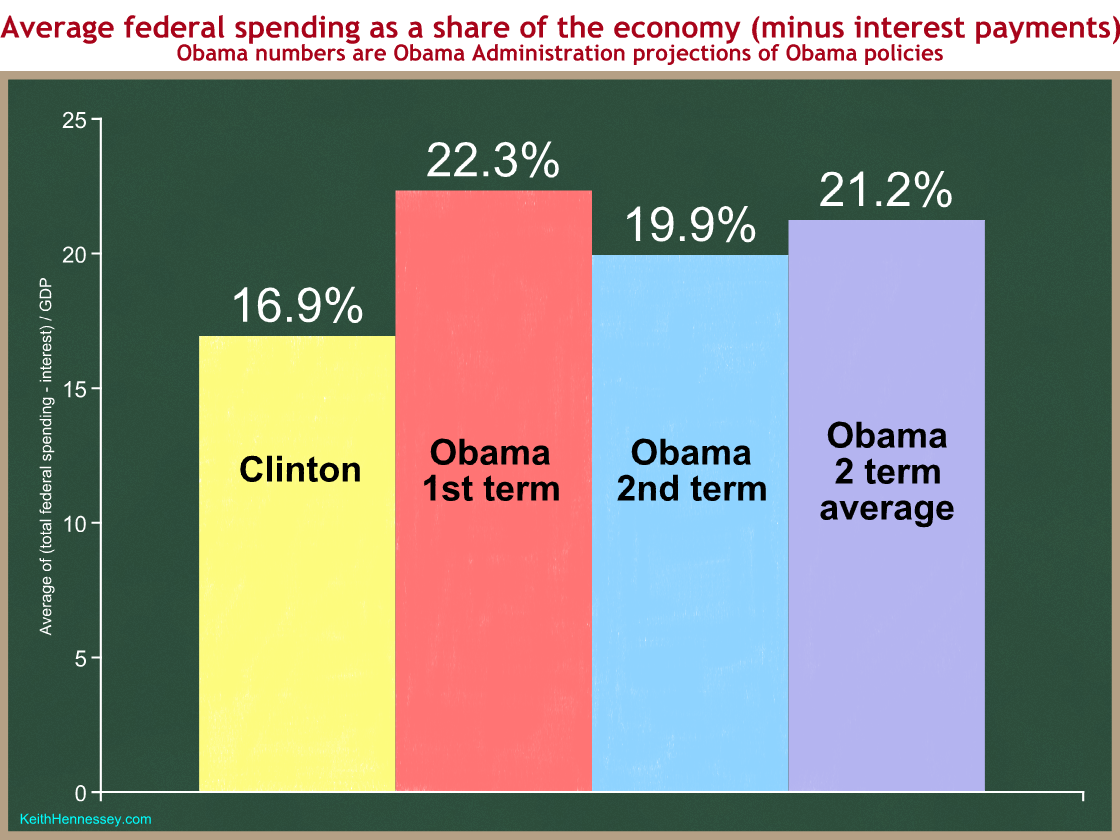

As much as I’m trying to make this not about the Bush tenure, some smart reader is saying to himself, “Yes, but Obama has to pay interest on the debt accumulated during the Bush Administration.” So let’s remove interest payments from both Clinton and Obama’s spending and compare them.

All columns are lower, but the comparison looks the same. President Obama would have a federal government more than four percentage points larger than President Clinton had, measured as a share of the economy. If President Obama has only one term it would be 5.4 percentage points larger. The higher Obama spending cannot be blamed on the additional debt he inherited from policies implemented during the Bush Administration.

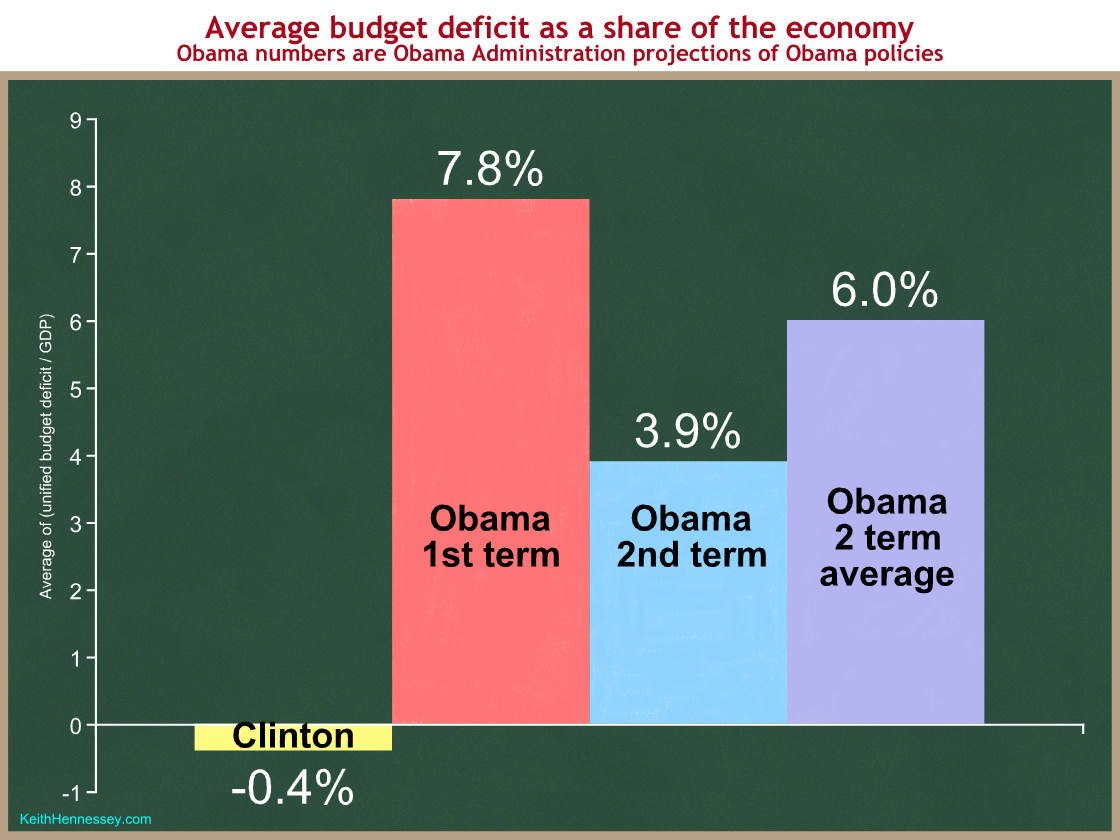

Now let’s look at deficits.

President Clinton averaged a surplus over his tenure. Using President Obama’s own projections of his policies, the budget deficit would average 7.8% of GDP over a first term, and 6% of GDP over two terms if he were reelected. Once again, it is absurd for Secretary Geithner to suggest that President Obama is returning to the Clinton fiscal policies.

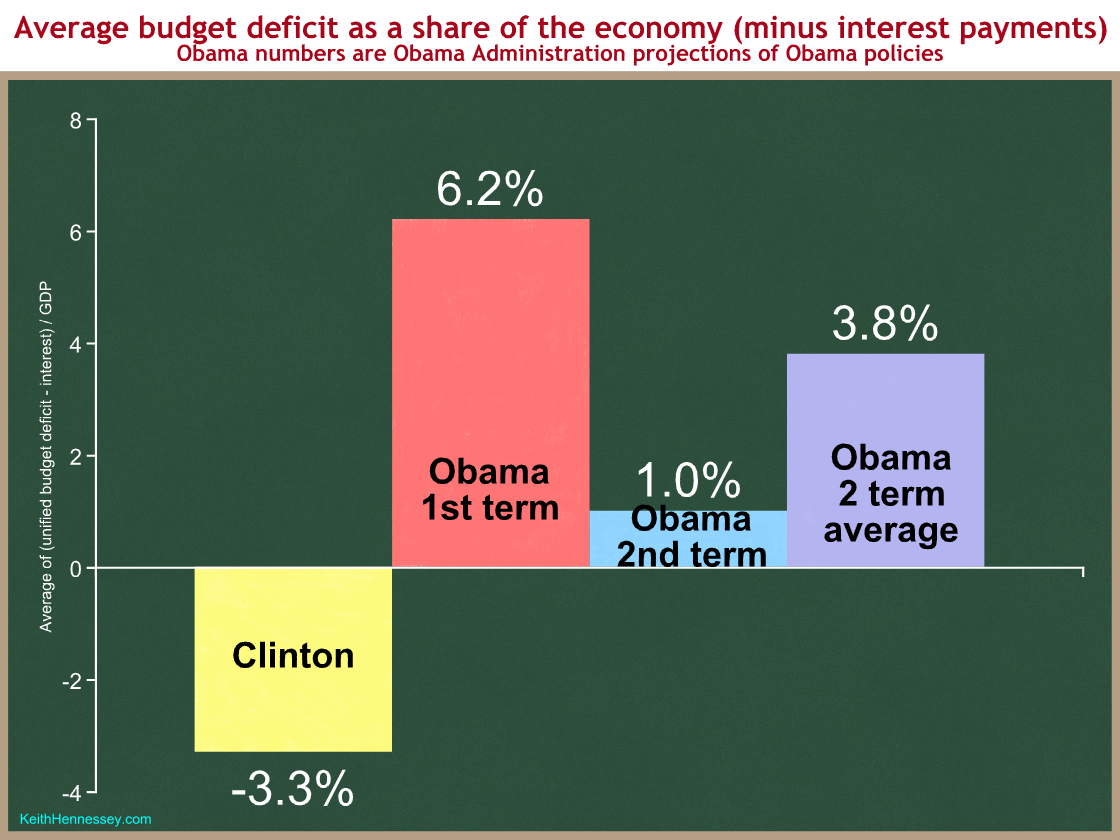

Once again, I’ll remove interest payments and recalculate the deficits to show that the difference between Clinton and Obama deficits is not the fault of inherited debt:

I hope these graphs disprove the Secretary’s implication that, by supporting a tax increase effective January 1, President Obama is somehow returning to the Clinton Administration’s fiscal policies. If anything, leaving out interest payments makes Obama’s fiscal policies look relatively worse.

Now let’s examine two measures of results, the unemployment rate and the growth rate of real GDP.

Team Obama projects that the President’s policies would result in 9 percent average unemployment over the President’s first term, and 7.6 percent average unemployment over two terms. Compare that to the 5.2% average unemployment rate during the Clinton Administration. Even in a hypothetical second term, after the financial shock is more than four years behind us, the Obama team estimates unemployment would average more than six percent in a second Obama term, worse than the average over the entire Clinton presidency.

And how about real economic growth?

This graph depresses me. The Secretary’s op-ed yesterday was titled “Welcome to the Recovery,” yet he and his colleagues project an average of only 1.4% real GDP growth over a two-term Presidency.

The good news is that everyone (and I do mean everyone) is just making wild guesses about GDP growth and the unemployment rate beyond one year in the future. Nobody really has any clue what the economy will look like two, three, or six years from now.

Washington and the press corps gravitate to partisan fights like Bush v. Obama. The Secretary’s remarks today feed that tendency. I believe the claims of the Clinton team that their policies caused the strong economic growth are exaggerations, and some other time I will engage in that debate. For today what’s most important is that the Obama fiscal policies are vastly different than those of the Clinton Administration, and the Administration’s own estimates project economic results far worse than we saw in the 90s.

I agree with Secretary Geithner Secretary that we need to restore America to a pro-growth tax and fiscal policy. I just don’t think that government spending of 24% of GDP, budget deficits averaging 6% of GDP, and raising taxes on successful small business owners during a weak recovery are that policy.

Billy Jones wants a bigger allowance

Irresponsible Billy Jones is once again spending more than his allowance. He is running up huge bills on the credit card his parents gave him. His parents cut his allowance nine and then again seven years ago and now Billy’s sister Suzy is debating some family friends whether a scheduled automatic increase in Billy’s allowance should be allowed to take effect January 1.

Self-anointed Wise Family Friends David, Fareed, and even Alan all argue that Billy’s parents should increase his allowance as planned. “Billy’s credit card debt is too big and it’s only going to get bigger,” they argue. “The responsible move is to increase Billy’s allowance as planned, and for Billy to use that higher allowance to reduce his monthly credit card borrowing. Eventually he needs to cut back on his spending as well, but this is a responsible first step.”

Eight-year old Suzy shakes her head because she’s heard this many times before. “Give Billy more money and he should use it to pay down his credit card,” she says. “But just look at what he’s done since January of last year. He has massively increased his spending to levels this family has never seen before. Sometimes he demands (and gets) more moneyfrom Mom and Dad to pay for his new spending. He has the gall to call that responsible since he’s not running up more credit card debt. He forgets that every dollar he takes from Mom and Dad is a dollar they cannot spend on the rest of the family’s needs.”

“For example, look at the new lifetime subscription he got to this new online game called ‘Universal Health Care.’ Sure he cut back on his monthly purchases of comic books to cover some of the costs, but he also demanded and received a big permanent allowance increase. Now that family money is committed to pay for his new subscription, and if he’s ever going to pay down his credit card balances, he’s going to have to cut other spending or, far more likely, demand an even bigger allowance increase from Mom and Dad. Once again, the rest of the family will lose out as we sacrifice resources to finance Billy’s unrestrained spending.”

Suzy continues, “Then there was the lemonade stand. ‘I’m going to borrow $787 on my credit card to build a super duper lemonade stand,’ Billy told Mom and Dad. ‘It will be such a success that not only will I make more money, but the whole family will benefit.’ We all know how that turned out, although Billy still claims it was exactly as successful as he had predicted, and that nobody had anticipated a cold summer would suppress demand for lemonade. Where is global warming when you need it?”

“Sometimes Billy spends and puts it on his credit card. When he does this he says it’s an emergency, even though everybody saw it coming months in advance. Or he calls it stimulus that will benefit the rest of the family, although I’m not sure his lemonade stand really needed a built-in stereo system.”

“Other times Billy spends and takes more allowance money from the rest of the family. When he does this he argues he is being responsible because he’s not running up more credit card debt. He calls it ‘paygo,’ which is a dumb name but I see what he’s trying to do. I am glad he’s not borrowing to pay for this new spending, but the dollars he takes from the rest of the family have real consequences for Mom, Dad, and me. We are worse off when Billy gets a bigger allowance.

Suzy continues, “Even scarier than Billy’s recent spending binges are the long-term spending commitments he has made. Billy has promised his many friends he would drive them wherever they want when he turns 16 next year, but we all know he won’t have enough money to pay for gas. He also told a bunch of girls that, once he gets his car, he will take them on dates to really expensive restaurants, and we know he doesn’t have that in his budget. Billy’s friends are getting excited about all these promises he’s been making for several years, which are coming due soon.”

“Billy should talk to his friends and tell them he’s going to have to scale back on those promises. He can drive his friends who won’t have a car, but those with cars of their own will have to drive themselves most of the time. And I’m all for Billy dating, but he needs to look for less expensive places to go. This family needs to rethink whether it can afford a lifetime subscription to Universal Health Care when we can’t pay for other needs. And Billy’s unrestrained spending binges have to stop. Billy needs to scale his spending way back. When he does so the explosion of credit card debt will stop, and the rest of the family will stop getting their needs shortchanged.

“Billy has historically taken about 18% of this family’s income for his spending, and he has typically run another 2% on his credit card each year. Now his annual spending has jumped from 20% of our family’s income to about 25%. Once we get out of this recession his allowance will automatically climb to an unprecdented share of family income, and Billy wants more. I’d like to start a small business designing apps for the iPhone, but I don’t think I can afford the startup costs if Mom and Dad give Billy even more money next year.”

“You’re only eight so you’re not Wise like us,” say the Wise Family Friends. “We must do something about Billy’s credit card debt.

Suzy responds, “Billy’s credit card bills scare me, too, but they’re the symptom, not the disease. The underlying problem is not Billy’s borrowing, it’s his out-of-control spending. You so-called Wise People miss three points. One is that you forget that increasing Billy’s allowance imposes costs on the rest of the family. Two is that Billy shows every sign that he will spend any allowance increase you give him, if not immediately, then soon thereafter. Third and most importantly, as long as his spending continues to grow at an unsustainable rate, you’re asking the rest of the family to make permanent sacrifices that at best will result in only temporary reductions in his credit card debt.”

The Wise Family Friends jump back in. “We all agree that Billy needs to cut his spending. We also agree that he will have to scale back the future promises he has made to his friends. Suzy, you may have to agree that Billy gets a bigger future allowance which means you and your parents will have less for your own needs. Living in a family is about making compromises. We will soon sit down and have a firm conversation with Billy about his spending. We will then see what we can get him to agree to as a combination of slower future spending growth and a bigger allowance.”

Flabbergasted, Suzy says, “And yet you want me to agree that Billy deserves a bigger allowance January 1st, before he has agreed to do anything about either his current spending binge or his unsustainable future spending promises? You say he needs the bigger allowance to pay off his credit card debt. You say he needs the bigger allowance in part to address those unfunded future promises.”

“Let’s look at the best case scenario. Suppose Billy takes that bigger allowance and uses it to not run up quite so much new credit card debt each month. The amounts he spends now are paltry compared to those future driving and dating promises. Billy turns 16 next year. What’s to prevent him from running his credit card debt right back up again on gasoline and expensive dates? By my calculations, if Billy gets a permanent allowance increase on January 1 and if he uses it to reduce his monthly credit card bills, in less than two years those new spending promises will drive his credit card debt right back to where it is now. The rest of the family will have fewer resources forever, Billy’s credit card debt will once again be too high, and his spending will still be growing faster than this family can support. You’ll probably come back to me at that point and explain that once again Billy need a bigger allowance. Who decided you were Wise anyway?”

“Trust us, you irresponsible little girl,” say the Wise Family Friends. “Take more money from the rest of the family and give it to Billy now. Unlike every prior allowance increase over the past 18 months, we hope he will save this one. And then in the future maybe we’ll get the whole family to sit down and debate how much more Billy’s allowance should increase, and how much we can convince him to scale back his promises to his friends.”

“That’s what scares me,” replies Suzy.

No sale to the press corps on unemployment insurance

While I was drafting yesterday’s skeptical post on the President’s partisan attack on unemployment insurance, I should have been watching White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs in the daily press briefing. From their questions it appears the White House press corps drew conclusions quite similar to mine.

Within hours the Senate will vote to invoke cloture on H.R. 4213, a “tax extenders bill” already passed by the House. I’ll gloss over some tricky process details, but the key substance is an amendment by Senator Reid.

The Reid amendment

Here are some details of the pending Reid amendment, courtesy of Senator John Thune’s staff on the Senate Republican Policy Committee and Senator Judd Gregg’s Budget Committee staff.

- The Reid amendment extends unemployment insurance benefits through November 30, 2010. These benefits would be retroactive to June 2, 2010, when the last law expired. No UI benefits under this law would be payable after April 30, 2011.

- The February 2009 stimulus law created a supplemental $25 per week UI benefit. The Reid amendment would not extend that provision.

- The $34 B of additional unemployment spending over the next decade would be designated as an emergency, meaning it would not be subject to paygo requirements and therefore does not need to be offset with other spending cuts or tax increases to avoid a 60-vote point of order.

- Despite intense lobbying from the States, the Reid amendment does not extend the higher federal match rate for Medicaid expenditures. If this Medicaid money doesn’t make it into this bill, it probably won’t happen as there are few other legislative trains leaving the station this year.

- The Reid amendment also contains a homebuyer tax credit provision that was separately enacted into law right before the Independence Day recess.

Assuming cloture is invoked this afternoon, Senator Reid will be able to offer amendments to modify his amendment with a majority vote. I expect he will strike the duplicative homebuyer tax credit provision. We will see if he tries to make other more significant changes.

The November 30 expiration date means Congress will wrestle with this question again in a post-election lame duck session in November/December.

Recent UI history

Courtesy of the staff of House Ways & Means Committee ranking Republican Dave Camp, here are the total Unemployment Insurance costs of seven laws and the new pending bill over the past recession and recent recovery period:

| Date | Law/Bill | CBO score ($ B) | |

| 1 | July 2008 | H.R. 2642 | 13 |

| 2 | Nov 2008 | H.R. 6867 | 6 |

| 3 | Feb 2009 | H.R. 1 (stimulus) | 39 |

| 4 | Nov 2009 | H.R. 3548 (offset) | 2 |

| 5 | Dec 2009 | H.R. 3326 | 11 |

| 6 | Mar 2010 | H.R. 4691 | 7 |

| 7 | Apr 2010 | H.R. 4851 | 13 |

| 8 | July 2010 | H.R. 5618 / H.R. 4213 (proposed) |

34 |

| Total spending | $125 B | ||

| Total offset | $2 B | ||

| Total deficit increases | $123 B |

From this table I draw a few conclusions:

- Assuming this new bill becomes law, Congress will have spent or committed $125 B for additional Unemployment Insurance benefits since the beginning of the recession. That’s not total UI spending, but the increment resulting from legislative action.

- Of this amount only $2 B was offset. The other $123 B increases the deficit and debt.

- This cuts both ways. Democrats can argue precedent, while Republicans can argue that past deficit spending makes offsets now even more necessary.

Team Obama’s intellectual inconsistencies on unemployment insurance

- The Obama Administration has previously supported offsetting the cost of extended UI benefits. In support of the November 2009 law (H.R. 3548) which offset $2 B of unemployment insurance spending, Team Obama’s Statement of Administration Policy said: “The Administration supports the fiscally responsible approach to expanding unemployment benefits embodied in the bill.” At the time the unemployment rate was 9.8%, higher than it is now.

- The President attacked Republicans for opposing deficit-increasing unemployment insurance extensions while supporting deficit-increasing extensions of tax relief. But the President has proposed extending much of that same tax relief without any offset.

- The President attacked Republicans for opposing extensions of UI benefits, while the Senate Republican Leader has explicitly supported such an extension on Sunday. The actual dispute is instead over whether the costs should be offset.

- White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs argued the bill should be passed without offsets to avoid legislative delay. But as a reporter’s question suggests below, that delay results from a disagreement between the two parties, and either side could have instantly resolved it by conceding on the offset dispute. The delay is the result of both sides prioritizing the budget offset question over immediate action.

A skeptical White House press corps

The White House press corps exceeded themselves yesterday in their questions of Mr. Gibbs after the President’s Rose Garden attack. The transcript does not identify specific reporters so we lose something by stringing all the questions together in sequence like this. As best I can tell, at least half a dozen reporters are responsible for the questions below.

You can see Mr. Gibbs’ answers in the full transcript. I find looking at just the questions interesting because it effectively conveys Team Obama’s message failure yesterday.

While the President will soon sign into law an extension of unemployment insurance, he failed to convince the White House press corps with his Rose Garden remarks.

Q: On unemployment, on the extension of the benefits, it looks like the Democrats will certainly have the 60 votes they need tomorrow to get past filibuster and move this into law. So with that being known, I’m trying to understand why the President did what he did today. What’s the point of calling out the Republicans if you know you’re going to have the votes?

Q: But does giving a statement like this in the Rose Garden, is it intended in any way to actually try to win one of the lawmakers’ support?

Q: Well, I guess that’s — just to wrap up on this point — I guess that’s my point, is that it seemed extremely clear what the President’s view is on this. He talked about it over the weekend, he’s talked about it in the past —

Q: So you don’t see this as the kind of political theater, the back-and-forth that the President was elected to stop?

Q: The President said Republican leaders in the Senate were advancing the misguided notion that the unemployment benefits discourage people from looking for a job, but the Republican leaders from Mitch McConnell on down have said that they are in favor of extending unemployment benefits but that they want the cost of that extension to be paid for with cuts to other programs. What’s wrong with that?

Q: But couldn’t Democrats have solved this instantly by simply saying, we’re going to extend unemployment benefits and we’re going to pay for it with offsetting cuts?

Q: But “pay as you go” is the very principle the President has put forward himself. They’re saying that now because of big deficits we need to pay our way.

Q: And let me just ask you one other thing on this. The so called “99ers,” people who have been unemployed for 99 weeks or more, their benefits are not going to be extended under this. Is the President aware of their plight? And does the President favor doing something to help them out?

Q: So you say that we ought not to be playing politics, and yet it seems that the President himself was suggesting that the Republicans were playing politics. He said, it was time to look past the election out there this morning. And yet when everybody knows this is going to pass tomorrow, how can you say that the President is not indulging in a little politics?

Q: But it’s not political to talk about it for the last four days knowing that you’re going to get it anyway?

Q: Quickly on unemployment, is there a line, once we drop below 9 percent the administration is not going to push for extending unemployment? When do you stop extending unemployment benefits? I mean, where’s that line?

Q: Do you anticipate in three months you’re going to be asking for another extension?

Q: Robert, if the President pushed for the reinstatement of “pay as you go,” what point was it if he is going to allow or go along with exemptions or exceptions for something like unemployment?

Q: But it’s spending. It goes on the deficit and in the debt.

Q: Could you apply PAYGO to unemployment benefits as quickly as not? Or are you saying it would take much longer?

Q: A follow-up again. Last month, when the issue came up in the Senate, the Republicans pointed to $50 billion in un-obligated stimulus money to pay for it, but Senator Reid objected. What would be wrong with taking that un-obligated money?

Q: I just want to make sure I understood what you were saying to Chuck about unemployment. You — the team essentially assumes right now — things could change — that unemployment is likely to be at 9 percent or higher by the end of this year?

Q: I threw that out to you — I said, is 9 percent the line with which you guys would stop asking for extensions? You said, it might be the line where we would stop, and then —

Q: And it is still an open question whether at the end of this year, at the end of November 30th, when these, if you get them, are due to expire, if you get them again?

Q: And just to follow up on Jonathan’s question, to Republicans who argue, yes, historically we have paid for these through deficit spending but we’ve never before had $13 trillion in the debt, we’ve never had a fiscal year situation except for last year where nine months into the fiscal year we’re already at a deficit of $1 trillion — conditions have changed and they require a different look and a different approach — to that you would say what?

Q: Coming at this from another direction, you described the unemployment situation as an emergency. Most economists don’t think we’re going to come rebounding out of this recession very quickly. Is there a point at which this relatively high level of unemployment becomes more of a chronic condition and therefore does in fact have to be paid for out of a regular budgeting process?

Q: Could they envision a time coming where they do, in fact, start —

Q: I’m wondering if it’s — and I understand what you’re saying, in the past it’s always been understood that in this kind of a recession it’s okay to add to the deficit for something like unemployment insurance. But if you can’t find $35 billion, how can the American people be confident that when it comes time to really solving the deficit and debt problem you’ll be able to find what you need?

Q: Are you talking about patching the roof with borrowed money or cash? That’s all. We’re not questioning whether you should patch the roof. It’s just how are you going to pay for it — with a credit card or with cash?

Q: You’re saying there’s no alternative to borrowing?

Q: But do you think it’s possible that even people on Capitol Hill who are being hypocritical have the support of the public in this because the public has this … feeling about the deficit?

While the President will win the vote, he lost the debate.

(photo credit: Jeremy Brooks)

When Presidents attack

This post is named after the Discovery Channel’s upcoming Shark Week.

President Obama spoke in the Rose Garden today about extending unemployment insurance benefits.

THE PRESIDENT: But even as we work to jumpstart job growth in the private sector, even as we work to get businesses hiring again, we also have another responsibility: to offer emergency assistance to people who desperately need it — to Americans who’ve been laid off in this recession.

In this context the word emergency has a technical meaning. It means “you don’t have to pay for it with offsetting spending cuts or tax increases.” I think it makes sense to extend unemployment insurance benefits now, but it is neither sudden nor unforeseen and therefore not an emergency. The $35 B deficit increase of the unemployment insurance benefits in the Reid amendment should be offset with spending cuts starting two or more years from now.

THE PRESIDENT: And I have to say, after years of championing policies that turned a record surplus into a massive deficit, the same people who didn’t have any problem spending hundreds of billions of dollars on tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans are now saying we shouldn�t offer relief to middle-class Americans like Jim or Leslie or Denise, who really need help.

It is incorrect to say “these people,” by whom the President means Congressional Republicans, “are now saying we shouldn’t offer relief to middle-class Americans.” Just yesterday Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said on CNN’s State of the Union:

LEADER MCCONNELL: Well, the budget is over a trillion dollars, too, and somewhere in the course of spending a trillion dollars, we ought to be able to find enough to pay for a program for the unemployed. We’re — we’re all for extending unemployment insurance. The question is when are we going to get serious, Candy, about the debt?

This is not a dispute over whether unemployment insurance benefits should be extended. There is broad bipartisan agreement that they should be. It is instead a dispute about whether the costs of that spending should be offset by other spending cuts.

The President draws the contrast with the enactment of the Bush tax cuts without offsetting the corresponding deficit increases. This is a genuine partisan policy disagreement. I believe all spending increases should be offset by other spending cuts. While I would prefer that tax cuts be offset by spending cuts, I would not insist on it. This view derives from my belief that our primary fiscal problem is a spending problem, and that large future budget deficits are a result of massive projected spending increases, not because taxes are “too low.” While Team Obama attacks this idea of one-sided paygo, they forget to mention that President Obama has proposed extending the bulk of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts without offsetting the deficit impact of doing so, putting him in the same position as President Bush. This suggests that President Obama’s logic is that it’s OK to extend “good” tax cuts without “paying for them,” but not “bad” tax cuts. Team Obama should be careful about accusing others of intellectual inconsistency on paygo.

Also, it is possible for people’s concern about the budget deficit to depend on both the proposed deficit-increasing policy and on the baseline deficit. In 2001 we (mistakenly) thought we were facing huge future surpluses. In 2010 we face record future deficits. It should not surprise anyone that Members of Congress are therefore more concerned about the deficits today than they were ten years ago.

Here’s the President again:

THE PRESIDENT: These leaders in the Senate who are advancing a misguided notion that emergency relief somehow discourages people from looking for a job should talk to these folks.

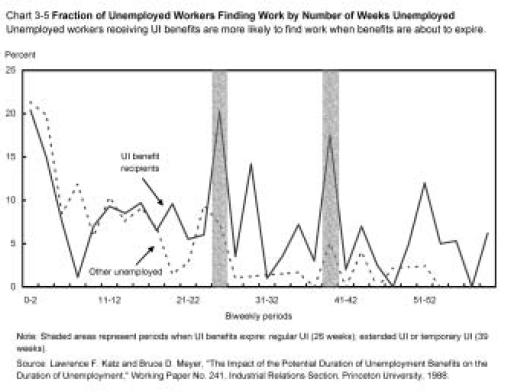

The evidence is clear that unemployment insurance does discourage some people from taking a new job. The President’s phrasing is slightly different, suggesting that it discourages

But there is a disincentive. The 2003 Economic Report of the President, written by President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers under its chairman at the time, Glenn Hubbard, wrote (p. 122 of the report, p. 119 of the PDF):

Any time that policymakers consider offering or extending UI benefits, they face a difficult tradeoff. UI can provide valuable assistance to unemployed workers, but it may also create a disincentive for benefit recipients to return to work. Unemployed workers who rationally evaluate their options may postpone accepting new work until their UI benefits are exhausted or nearly exhausted. The result is higher unemployment and longer average spells of unemployment. In the study cited above, for example, 40 percent of those who had not received UI benefits, but only 35 percent of those who had, returned to employment within 4 weeks of their job loss. This 5-percentage-point difference hints at the disincentives built into UI, since fewer of those receiving it returned to employment quickly. Another study found more direct evidence: each additional week of UI benefits was estimated to increase the duration of the average unemployment spell by about a day. Many other studies have also found an association between the level of weekly UI benefits and the duration of unemployment. Still more evidence comes from Europe, where most countries have more expansive UI policies than the United States and have higher rates of unemployment and longer average unemployment spells. Although these differences in unemployment outcomes may not be due to differences in UI policies alone, the totality of the evidence suggests that they contribute.

And this graph hammers the point home (sorry for the small size, it’s the best I’ve got):

Chart 3-5 illustrates another aspect of the relationship between the availability of UI benefits and incentives to find a new job. Unemployed workers who receive UI benefits are more than twice as likely to find a job in the week before their regular benefits expire than in the several weeks immediately preceding. As noted above, UI benefits expire after 26 weeks unless extended, in which case they expire at 39 weeks (for workers receiving either extended UI benefits or temporary extended UI benefits). Perhaps not coincidentally, peaks in the fraction of unemployed workers finding work also occur around these expiration dates. Among unemployed workers who do not receive benefits, in contrast, there is no substantial difference in the likelihood of finding a job at these points in their unemployment spell.

This graph comes from a paper written by the former Chief Economist for the Department of Labor during the first two years of the Clinton Administration, Dr. Lawrence Katz.

I wrote about this tradeoff a little while back. For me this breakpoint occurs at about 8% unemployment. Above 8% and I don’t worry too much about the disincentive for some to take a new job, given that there are so many others who would take a job but can’t find one. Below 8% I worry much more about the disincentive and would lean against an extension of almost two years (99 weeks) of UI benefits.

The President’s attack today is part of a set piece. With Sen. Byrd’s replacement Carte Goodwin being sworn into office today, Team Obama knows they now have 60 votes to shut off debate on the Reid amendment and to enact the UI extension the President wants without having to offset the deficit increase. By sending the President out today to urge for this to happen, he can try to take credit after it does, even though there is almost no uncertainty left about the final outcome.

Is Team Obama contingency planning for a Republican House?

Yesterday I endorsed the President’s nominee for OMB Director, Jack Lew. Far more importantly, I see that Budget Committee Ranking Minority Members Paul Ryan (House) and Judd Gregg (Senate) endorsed Mr. Lew. This tells me his eventual confirmation is a slam dunk.

In a follow-up email conversation a well-connected Republican friend stressed the intensity of internecine warfare among DC Democrats right now. To this insider, Democratic House and Senate Leaders appear to be at each other’s throats, largely over Leader Reid’s inability to pass bills that in the past have been routine (like extenders + UI), as well as a belief among some House Democrats that the White House uses them as “cannon fodder.”

White House Press Secretary Robert Gibbs’ comment this weekend that Republicans might take the House created a dustup with House Democrats that continues to swirl. I then read Dana Perino’s post about the Pelosi-Gibbs spat and what it may tell us about White House thinking. Key quote:

Democrats know they’ll lose seats in November – I think what surprised people is that their internal polling at the White House must be such that they really think they could be dealing with a Republican House majority for the next two years.

My friend and I surmised that this Democrat-on-Democrat violence results in large part from their fear of losing seats or even the majority, driven by the combination of a weak economy, huge budget deficits, and no apparently effective policy solution to either. In my experience it’s very hard to keep a partisan majority working together as a team when that majority is threatened — individuals are less willing to “take one for the team” and worry far more about what they need to do to keep their own seat.

Combining Republican support for Mr. Lew, with Democratic intraparty squabbling, with Dana’s hypothesis about the White House’s view about the fall elections leads me to a hypothesis.

Of the candidates publicly discussed for OMB, Mr. Lew is the one most likely to draw praise from Republicans, and the President’s team is smart enough to know that. There are plenty of reasons why Mr. Lew will make a good budget director, and I detailed them yesterday.

At the same time, I wonder if the President’s selection of Mr. Lew in part reflects a view among Team Obama that they may be dealing with a Republican House Majority next year. At a minimum it’s an added bonus and smart contingency planning on the part of the White House, albeit at the expense (once again) of their House Democratic allies.

Put it this way: as President if you somehow knew you would face a Republican House majority next year, you’d want a budget director who could work with them while ardently defending your policy views. Jack Lew would be that guy. Team Obama cannot possibly know this, but I wonder if Dana is right — maybe they think they could be dealing with a Republican House majority for the next two years, and maybe they’re starting to play for that possibility.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)

Jack Lew for Budget Director

Today the President announced his intent to nominate Jack Lew as Director of the Office of Management and Budget. I support Mr. Lew’s nomination. Mr. Lew is extremely well-qualified for the position and should be quickly confirmed. While I think I will disagree with him on many policy issues, he is an honorable man, a responsible policymaker, and a good pick for this President.

Here is the White House fact sheet on Mr. Lew. He is now serving as Deputy Secretary of State for Management and Resources at the State Department. In the Clinton Administration, he served as Deputy Director of OMB, then as Director, so this would be his second stint in this role.

I got to know Mr. Lew a little during his Clinton Administration service when I worked on budget issues for then-Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott. I don’t know him well but was always impressed when I interacted with him. At the time he was usually sitting across a negotiating table from my boss. I negotiated directly with him a couple of times, although not on anything major.

Here is why I think Mr. Lew will be a good budget director.

- He is an honest budgeteer. Many in Washington want to skew numbers to avoid having to make hard tradeoffs. An honest budgeteer spends personal capital to fight those who would use scoring gimmicks to disguise the costs of their preferred policy. Honest budgeteers get sneered at a lot, often by colleagues within their own party. It’s sort of like having a tough but fair referee — players come to respect them even when they disagree with a particular call. I expect I will disagree with many of the policies Mr. Lew will publicly advocate, but I think he’ll be honest and transparent about them.

- He is a straight shooter in dealing with Congress. Mr. Lew was a very tough negotiator, but he never let it get personal, and he always seemed to be trying to work toward a solution. I never felt like I had to double-check what he was telling me or my boss, and I felt that his word was good. This didn’t always mean that it was easy to negotiate with him — I remember him as someone who would unfailingly stick to his negotiating position even if everyone in the room was yelling at him, if that’s what his boss wanted him to do. I would have liked him to have been more flexible at times, but I always felt like he was playing straight with my boss and me.

- He is a manager. OMB has an enormous role to play in helping the President manage an unwieldy Executive Branch bureaucracy. I think there is a high likelihood Mr. Lew will devote more attention to management than we have seen so far, and that the OMB career staff will be empowered to make sure the President’s policy goals are being implemented as efficiently as possible. This does not mean that money won’t be wasted, but instead that some of the worst bureaucratic inefficiencies may be trimmed. OMB needs a Director who listens to and strengthens the career OMB staff.

- He has a low-ego loyal staff / agent approach. Like Treasury Secretary Geithner, Mr. Lew worked his way up from being a staffer. (I am biased in favor of this background.) Some Cabinet-level officials make the mistake of thinking they are the boss, and that their job is to implement their own policy views, rather than those of the President. I think a great Presidential advisor is one who advocates vigorously for his views behind closed doors, and even argues privately with the President when necessary, but who does not trumpet his own views or his recommendations to the world at large. When you work for the President you’re supposed to talk publicly about the President’s views, not your own. I anticipate there will be no daylight between Director Lew’s views and the President’s, and I don’t think we’ll see press reports about how the President is accepting his budget director’s recommendations on X.

- He understands the value of the budget process. One of the great travesties of this year is Congress’ failure to enact a budget resolution and the breakdown of the traditional budget process. This breakdown is certain to lead to poor decision-making. I am hopeful that Mr. Lew, who has participated in many budgets, will help restore some order and structured decision-making. Let’s have policymakers make some choices rather than just having a spending free-for-all.

- He can fight and he can compromise. A President needs a budget director who can do both. I have seen Mr. Lew do both, and he’s equally good at both. With an expanded Republican presence expected in Congress next year, the new Budget Director will need both skills.

- He is smart, knowledgeable, strong and experienced. OMB will be more powerful as a result of his bureaucratic knowledge, strength, and experience. While he may get rolled by a free-spending President and/or West Wing staff, I expect a power shift from the Cabinet to OMB as Lew enforces stronger spending (and regulatory?) discipline.

I don’t know Mr. Lew’s personal policy views well because every time I dealt with him (10+ years ago) he only talked about what his boss President Clinton wanted. My impression, however, is that he is neither particularly liberal nor particularly conservative for the Democratic party. I don’t think of him as a Blue Dog Democrat, nor as a big spending liberal. I would like President Obama to have a budget director with views closer to my own. But I can be comfortable with one who may be more liberal than I would like, but who has other personal and professional qualities that I think comprise a responsible policymaker. I anticipate disagreeing with many of the policies Mr. Lew will soon advocate, in many cases quite vigorously. I am hopeful, however, that his presence at OMB will elevate the fiscal policy debate and that he will provide honorable service to the President and to the Nation.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)

A decade of spiraling deficits

Last Friday while speaking at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas about the economy, President Obama said:

And these were all the consequence of a decade of misguided economic policies — a decade of stagnant wages, a decade of declining incomes, a decade of spiraling deficits.

I want to focus on that last phrase: a decade of spiraling deficits.

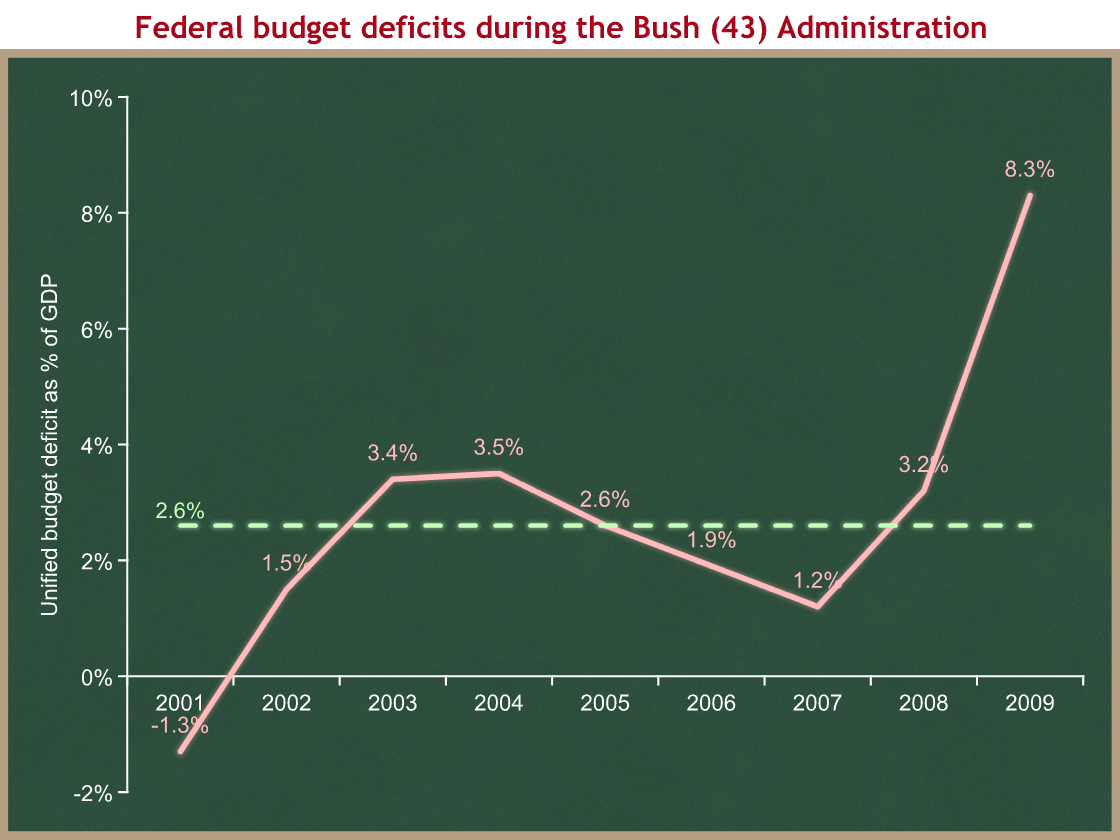

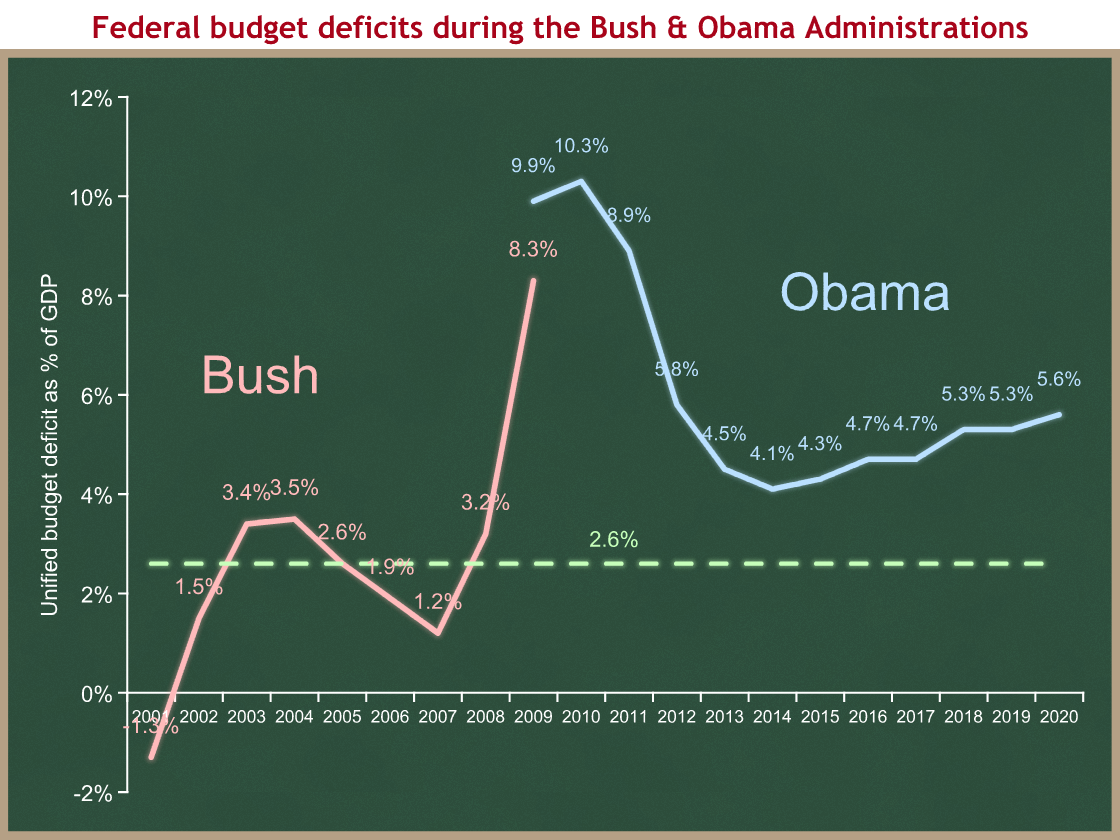

The best way to compare deficits over time is as a share of the economy. This first graph shows budget deficits during President Bush’s tenure. On this graph deficits are positive, so up is bad. The dotted green line shows the average deficit since 1970 for comparison (2.6% of GDP). As always you can click on the graph for a larger version.

This graph does not show “a decade of spiraling deficits.” It instead shows eight years of deficits averaging 2.0 percent of GDP, followed by a horrible ninth year as the markets collapsed and the economy plunged into recession. (Budget wonks who want to understand why I think we should look at nine years for a Presidency rather than eight can read this.) Even 2008’s bigger deficit than 2007 can be mostly explained by a revenue decline as the economy slipped into recession pre-crash. Before the crash of late 2008 President Bush’s budget deficits were 0.6 percentage points smaller than the historic average. Deficits did not “spiral” during the Bush presidency or the decade. They bumped around the historic average, then spiked up in the last year.

Yeah, but what about that horrible 8.3% in 2009 when President Bush left office? That figure is a combination of a severe decline in federal revenues as the economy tanked, plus the projected costs of TARP for fiscal year 2009. If we include that terrible ninth year in the Bush average (as we should), then the average Bush deficit is still only 2.7%, one tenth of a percentage point above the average over the past four decades. (All data are from CBO’s historic tables.)

Yes, that last year sucked. Yes, when President Obama took office he faced an enormous projected budget deficit for his first year in office (which jumped from 8.3% when President Bush left in January to 9.9% at the end of that fiscal year). But it is inaccurate and misleading to characterize the previous decade as “a decade of spiraling deficits.”

Am I making too big a deal out of one phrase? I don’t think so, because President Obama’s economic and political argument centers on redefining the entire Bush tenure as an economic failure. There is therefore a big difference between “a decade of failure” and “seven years-of-pretty-good, followed a disaster in year eight.”

One could argue that the last year was a result of policies built up during the prior seven years, but that’s a different argument about financial sector policies. Instead the President and his allies are claiming that the President’s policies resulted in “a decade of spiraling deficits.” That is obviously false.

Now let us look at the decade we are now beginning. The blue line shows CBO’s estimate of projected budget deficits if President Obama’s latest budget is enacted as proposed. Numbers are once again from CBO.

Which exactly is the decade of spiraling deficits? The last one, or the one we’re beginning now?

For comparison:

- Bush average: 2.7% (including the 8.3% for FY 2009 when President Bush left office in January);

- Obama average (projected for two terms spanning nine fiscal years): 6.35%

If you’re disturbed by looking at nine budget years for an eight year Presidency, I wrote this to explain why I think it makes sense.

This graph shows a sharp projected decline as we recover from the crash/recession followed by a steady upward climb. If President Obama’s budget is enacted as proposed, his smallest budget deficit will be bigger than the largest pre-crash Bush deficit.

Let’s look at it another way. Let’s focus only on a hypothetical second term for President Obama, when the effects of the 2008 crash and 2009 recession are far behind us. A second Obama term would span five budget years: FY 2013 through FY 2017. CBO says the budget deficit would average 4.5% in that second term. That’s almost two percentage points above the historic average, 1.8 points above the Bush full-term average including the crash year, and one point higher than the highest pre-crash Bush deficit.

The steady deficit climb under the Obama budget that begins in 2014 looks like it fits the description “spiraling deficits” for at least the last seven years of this decade.

President Obama is incorrect when he labels the last decade as one of “spiraling deficits.” The Bush presidency was characterized by eight years of deficits with no long-term upward trend and which averaged significantly less than the historic average, followed by a financial crash and a year of severe recession and a consequently large deficit.

If the President is right when he says that “a decade of spiraling deficits” are “the consequence of a decade of misguided economic policies,” he is looking at the wrong decade. I don’t see how he can justify his own budget.

Methodology: How to compare Presidencies over time

This is a wonky methodology post that some readers may want to skip. I am including it because I need to use it in another post today, and I anticipate I may need it again in the future.

Economists often cringe when people try to compare economic outcomes across presidencies. Economists generally think the right way to compare short-term macroeconomic performance is to compare business cycles, and the timing of business cycles never matches up perfectly with the electoral calendar.

Budget analysts have an additional problem: the federal fiscal year begins October 1, so in a Presidential transition year one budget year spans two Presidencies.

There’s a third unsolvable problem, which is that many economic policies work with a long lag. President Bush’s first year macroeconomy was in part defined by the after effects of the tech bubble collapse of 2000, before he took office. Similarly, President Obama’s first year was heavily shaped by a financial crash that happened four months before he took office.

Still, the policy debate and political process requires that we find a fair and objective way to compare economic and fiscal outcomes across Presidencies.

For budget data I think the best way is to look at the nine budget years spanned by a President’s two terms, and to measure that ninth year mid-year, when he leaves office. (For a one-term President we would examine five budget years.)

This is easiest with a concrete example. CY stands for Calendar Year and is measured January 1 – December 31. FY stands for (federal) Fiscal Year and is measured October 1 – September 30.

- In CY 2000, his last year in office, President Clinton negotiated with Congress on the spending and tax bills for FY 2001, which began October 1, 2000, almost four months before President Bush took office.

- In January 2001, CBO estimated the budget outlook for FY 2001 based on the laws signed into effect for FY 2001 by President Clinton.

- President Bush worked with Congress to quickly enact the 2001 tax cuts. That law significantly changed the FY 2001 budget outlook. So even though President Clinton determined much of the FY 2001 budget, we need to hold President Bush responsible for FY 2001 as well since (a) he served for eight of its 12 months and (b) he had a big effect on it. This is true even though President Clinton shaped most of the FY 2001 budget.

- President Bush was in office for all of FY 2002 through FY 2008. That’s seven more years. We’re up to eight.

- FY 2009 began October 1, 2008. TARP was enacted in the first few days of that fiscal year, and we committed more than $300 B in the last four months of the Bush presidency, which also were the first four months of FY 2009.

- President Bush therefore should be held accountable for FY 2009 as it was projected when he left office in January, 2009. Lucky for us, CBO releases its annual Economic and Budget Outlook with a new baseline each January, so we have an independent estimate of that ninth year before any Obama policies take effect.

Therefore the best and fairest way to measure fiscal policy over the Bush Administration is to look at nine budget years:

- FY 2001 actuals, even though President Clinton was responsible for much of its shape;

- and FY 2002 – FY 2008 actuals;

- and FY 2009 as estimated by CBO in their January 2009 Economic and Budget Outlook.

The same holds true for any other President. While President Bush should be held accountable for the projected FY 2009 budget outlook (his “ninth” year) when he left office, President Obama should be held responsible for the final FY 2009 outcome, including any policies he signed into law and any economic changes that occurred in the eight months of that year when he was President.

You can see this works nicely for the Bush-Obama transition:

- Bush’s TARP spending ($300+ B) goes on Bush’s account, as does the decline in revenues that occurred in FY 2009, during part of which he served as President.

- Obama’s TARP spending and Obama’s stimulus goes on Obama’s account in the FY 2009 actuals, as does any further weakening of the economy and revenues after Obama took office.

The downside is that policies occurring in the first four months of the first fiscal year of a Presidency are largely shaped by one’s predecessor. That’s undesirable, but to some extent each President “inherits” the sum total of everything that comes before them, and I don’t know any way to avoid this without causing more measurement inequities.

This methodology leads to the slightly surprising result of calculating fiscal policy averages over nine years for a two-term President, and over five years for a one-term President. It also means that boundary years get attributed to two Presidents (albeit measured at different times). This feels a little odd but after some thought it seems to make sense.

This methodology is imperfect but it’s the best I can construct. It’s not fair that Bush’s first measured year was largely shaped before he took office, nor that Obama’s measured first year was largely shaped before he took office. But any other way of measuring Presidencies (like attributing all of FY 2009 to Bush) runs into bigger problems – surely Bush shouldn’t be assigned the budget effects of the Obama stimulus, any more than Clinton should be assigned the budget effects of the Bush tax cut.

If anyone can suggest a way to improve this methodology (and not just point out its flaws, please) I would love to hear it. I want/need something which is objective, rule-based, and fair.

How to enact a bipartisan stimulus (and why it won’t happen)

Concerned about both the weak economy and its political consequences for the Administration, the President and his advisors would like to enact more fiscal stimulus. Yet they know they cannot get the votes to increase spending. Congressional Republicans are unified against deficit-increasing spending for any goal. Enough Congressional Democrats have joined them that the President’s first choice is impossible. The supposed policy positions look like this.

Do you support fiscal stimulus?

| through spending increases yes | through spending increases no | |

| through tax cuts yes | 1 | 2 |

| through tax cuts no | 3 – The President & Congressional Democrats |

4 – Congressional Republicans & a few Democrats |

The intellectually pure fiscal stimulus positions are boxes 1 and 4.

The President and most Congressional Democrats are in box 3. They support fiscal stimulus but only in the form of increases in government spending. We saw this when the House recently passed a bill in which Blue Dogs insisted that any tax cuts be offset by other tax increases, but were quite comfortable using a fiscal stimulus argument to justify increased government spending that increased the deficit.

While Congressional Republicans claim they are in box 4, I believe most of them would actually be in box 2 if presented with the opportunity. They would be happy to support short-term fiscal stimulus if it were implemented in the form of tax cuts, and they are using anti-fiscal stimulus arguments as a way to argue against the only stimulus likely to be enacted, through increased government spending.

While the Administration and its allies try to enact spending increases, under current law taxes are scheduled to increase effective January 1 of next year:

- the individual income tax rates will increase from 10/15/25/28/33/35 to 15/28/31/36/39.6;

- the per-child tax credit will decrease from $1,000 to $500;

- capital gains tax rates will increase from 5/15 to 10/20;

- dividends will be taxed as ordinary income, rather than at 5/15 percent rates; and

- the estate tax will return to life, with a $1 million exemption and a 60 percent top rate.

CBO estimates these tax increases will increase federal revenues and reduce the budget deficit by about $170 B in 2011. If you are a big believer in fiscal stimulus that is a huge contraction. That amount is bigger than the deficit increase in that year resulting from the President’s Feb 2009 stimulus law.

The President and his Congressional allies propose to allow only the “taxes on the rich” to increase. From the above list they would allow the 33% and 35% individual income tax rates to increase to 36% and 39.6%. They would allow the capital gains and dividends tax rates to increase and maybe create a tiered structure so that higher rates apply only to those with higher incomes. And they would allow the estate tax to return, albeit with a larger exemption and a lower rate. These are longstanding Presidential commitments and now qualify as Democratic party dogma.

They are also anti-stimulus. A better word might be “contractionary.” The Administration says their policies would raise taxes on the rich and reduce deficits by about $45 B in 2011. That is almost 50% larger than the deficit effect of the pending proposal to extend unemployment insurance benefits.

While these tax increases would reduce the deficit, they have negative economic effects as well:

- Any tax increase leaves less money in the hands of private individuals and firms to do with as they see fit.

- The top marginal income tax rates apply not just to rich individuals and families but also to successful small businesses. The President and his allies are proposing higher taxes on small businesses in a weak economic recovery. That is bad policy and terrible politics.

- Uncertainty about future tax rate increases is a factor in firms hoarding cash. We need firms to hire workers and increase investment.

- Lowering the dividend tax rate in 2003 reduced the tax incentive for corporations to hoard cash. Dividend payouts increased. Allowing dividend tax rates to increase will encourage corporations to hoard even more cash than they are now.

The President could trap Republicans in their own anti-fiscal stimulus rhetoric by proposing to extend all the Bush tax cuts for, say, two years along with extending unemployment insurance. I believe Congressional Republicans would quickly shift from box 4 to box 2 above. Both Congressional parties would be exposed for their intellectual inconsistency on fiscal stimulus while they enacted a bipartisan law.

Let’s look at the benefits of this:

- If you’re a believer in fiscal stimulus, then this is additional stimulus that you can enact now. It’s not big, but when combined with an extension of unemployment insurance it’s almost $80 B over the next year. That is still only about half a percent of GDP, but it’s the best they can get out of this Congress, and the tax cuts would have an effect immediately as uncertainty is eliminated and expectations change.

- This policy would help small businesses and eliminate tax uncertainty for all businesses for two years.

- Keeping the dividends rate low would eliminate the added incentive for corporations to hoard cash that will occur next year if the President’s policy is enacted.

- The President could demonstrate that he can be bipartisan.

- By enacting it for two years he can once again tee up “tax cuts for the rich” as a political issue in election year 2012.

This would create the same legislative coalition that enacted the 2008 stimulus negotiated by Speaker Pelosi, Leader Boehner, and then-Secretary Hank Paulson after President Bush proposed it. With Presidential leadership such a coalition could be rebuilt today.

The idea is not without costs for the President:

- Spending-side stimulus advocates will correctly point out that some of the tax relief would be saved rather than spent. They will forget to mention that the stimulative bang from tax relief will occur immediately, while government spending has its effect slowly.

- The President would have to temporarily reverse himself on a core element of his economic policy. It would also undercut his “blame Bush” message.

- Even when combined with an extension of unemployment insurance benefits, the stimulative bang is smaller than someone like Dr. Krugman would argue is needed.

- This move would split Congressional Democrats, many of whom could not imagine voting either for the policy or to extend President Bush’s legacy.

- It would similarly anger many in the Democratic political base, upon whom Congressional Democrats are depending to prevent a rout this November.

For the above reasons this idea won’t happen, but I think it is a useful thought experiment to illuminate the intellectual inconsistency on both sides of the fiscal stimulus debate. On this I agree with Megan McArdle:

Wading through the online debates, I note that opinions on stimulus are nearly 100% correlated with the composition of that stimulus, and the opinionator’s prior view of that activity. So when Democrats are in power and stimulus is mostly spending, liberals think that the stimulus is an issue of fierce moral urgency stymied by venal greed and rank idiocy, while conservatives develop deep qualms about budget deficits. When Republicans are in power, and stimulus consists mostly of tax cuts, Democrats get all vaporish about deficits and the income deficit, while Republicans suddenly realize that the normal rules don’t apply in an emergency. When out of power, both sides will grudgingly concede that some small amount of highly temporary stimulus might be all right, but note (correctly) that the other side seems to be trying to make permanent as much of this “stimulus” as possible.

For me, then, this mostly ends up as a proxy war over the level of government spending, a war I’d rather fight honestly on value grounds rather than attempting to disguise my preferences with a shoddy veneer of “scientific” logic.

As President Obama ramps up his partisan campaign blame rhetoric, remember that he is choosing not to pursue this bipartisan option that would enact more fiscal stimulus and extend unemployment insurance benefits while preventing tax increases on small business owners during a too-slow economic recovery.

(photo credit: fazen)

Extending unemployment insurance

I would like to offer a few thoughts on extending unemployment insurance.

Supply-side effects & the tradeoff

There are negative supply-side effects from providing unemployment insurance (UI) benefits. The best estimates I have seen suggest the current 9.5% unemployment rate is 0.5 – 1.0 percentage points higher than it would otherwise be because of previously-enacted expanded and extended UI benefits. I will start by using the bottom end of that range (0.5).

I use 5.0% to represent full employment. We are 4.5 percentage points above that. If we did not have expanded UI we would be 4.0 percentage points above full employment. That means for every 9 people out of work, one is being discouraged from taking a new job because of the expanded benefits (0.5 / 4.5). Said another way, eight people who would like a job but cannot find one are getting more generous UI benefits for each person who is getting those same benefits and choosing not to take a new job. We have to make a tradeoff between our desire to help those who want a job but cannot find one and those who would choose to stay unemployed while they have extra benefits.

The judgment call for policymakers: does an 8:1 ratio make a UI extension good policy? I say yes. If, however, the supply-side disincentive is a full percentage point, then we have a 3.5:1 ratio. That is a tougher call, but I would still say yes. Given the range of possible supply-side disincentives, I would recommend extending UI benefits when the unemployment rate is 9.5%.

I assume that most everyone would agree that at full employment it is foolish to provide more generous UI benefits. So somewhere between 5.0% and 9.5% there is a breakpoint at which the supply-side disincentive is not worth the compassion benefit of providing aid to others who want a job but cannot find one.

At a 7% rate our ratio is between 1:1 and 3:1. At an 8% rate it’s between 2:1 and 5:1. My breakpoint is around 8%. I would support a (paid for) UI extension as long as the rate is 8% or above. There is nothing magical about this judgment, and yours may differ.

Stimulus effects

The fiscal stimulus argument in favor of extending UI benefits is silly. The numbers are too small. The pending legislation would spend $33 B over the next year on UI benefits. In a $14+ trillion economy, that’s less than one-quarter of one percent of GDP. When you’re running a 10% deficit, another 0.2% is not meaningful. Sure you can argue that “every little bit helps,” and yes the unemployed are likely to spend almost all of the assistance they receive. But the reason to extend benefits is to help those people who would receive them, not because the cash will significantly accelerate economic growth and benefit everyone else. If this $33 B of spending were concentrated into a month or two it might be barely big enough to register, but it would be spread out over the next year. $3 B per month is a lot of money, but not when compared to a $1+ trillion per month economy.

For instance, the second (bolded) phrase of this statement by Speaker Pelosi is a huge stretch: “These benefits help struggling families make ends meet, boost consumer demand to spur hiring by small businesses, and strengthen our economy as a whole.” This effect is so trivially small that no one could reasonably claim to estimate or measure it.

The Republican position

While a few Congressional Republicans are arguing that UI benefits should not be extended, the overwhelming majority are for an extension as long as the deficit impact is offset. The $33 B deficit increase could be offset immediately by other spending cuts or tax increases. For those who ignored my last point (too small to matter from a macro fiscal stimulus perspective), you could easily offset the $33 B by enacting changes now that would reduce spending by $33 B beginning three or four years from now. This eliminates the “contractionary” excuse for not offsetting the spending increase.

There is overwhelming bipartisan supermajority support for a UI extension if it is offset. Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid chose not to follow this path, presumably because it would split their side of the aisle. They instead chose a partisan route that resulted in partisan stalemate, and we are now in the midst of a traditional blame game. Do not be fooled into thinking this is a debate about whether to extend UI benefits. It is instead a debate about whether that increased spending should be offset by spending cuts or instead increase the deficit.

Reducing the supply-side disincentive

There is a simple way to reduce the labor disincentive from expanding and extending UI benefits. In 2003 President Bush proposed personal reemployment accounts as a substitute for expanded unemployment insurance benefits.

The program would have spent $3.6 B to provide 1.2 million unemployed people who are least likely to quickly find a job with a $3,000 account. That person could make regular incremental withdrawals from the account for reemployment services: job training, search services, transportation costs, child care, or even getting a suit cleaned for interviews. If the person started a new job within 13 weeks of receiving his first UI payment, he could keep any balance in the account as a cash reemployment bonus. If he did not, he could continue making regular withdrawals from the account to use for reemployment services while receiving UI benefits.

This bonus feature would reduce the incentive for workers to remain unemployed so they could keep receiving benefits. A worker who takes a job today will get part of that future stream of benefits in a lump sum payment.

Unemployed workers are not a uniform population. Some need help with their job search, while others need retraining. Still others need transportation or child care while they look for work. Rather than having government determine how to allocate these funds for the unemployed, a PRA would allow a worker to decide how best to use his account funds for any purpose related to finding a new job.

Reemployment bonuses have been tried in the past. In the 1980s experiments were conducted in Washington, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. Workers were provided with reemployment bonuses of between $300 and $1,000 if they found a job before their UI benefits expired. These bonuses reduced the amount of time workers remained unemployed by about a week, and the new jobs they took were comparable to those who did not get bonuses.

In the recession of 2003 Congress rejected (ignored, really) President Bush’s PRA proposal on a bipartisan basis. At the time a cynical legislative expert friend said, “Republicans hate personal reemployment accounts because they know they won’t work. Democrats hate them because they know they will.”

Recommendations

- Congress should extend unemployment insurance benefits as long as the unemployment rate is above 8%. I would extend the law for six months and then reevaluate.

- Congress should offset the deficit increase from this new spending by cutting an equal amount of spending, effective three or more years from now to remove the silly anti-stimulus argument.

- Congress should allow States to instead use the additional funds to experiment with personal reemployment accounts for those who are hardest to reemploy.