Speaker Pelosi’s Last Big Decision

House Democrats’ practical transition to minority status precedes the formal transfer of power on January 5th. Speaker Pelosi has one big decision to make before she becomes Minority Leader: Will she bring up a Senate-passed tax bill for an up-or-down House vote?

Procedural summary

On Thursday the tax deal was released in legislative form, surprisingly labeled the Reid/McConnell amendment. You don’t see that every day on a big economic issue. Senate Republican Whip Kyl supports it, and in the Senate we therefore have an Obama-Reid-McConnell-Kyl alliance. That’s unbeatable and will clearly get the 60 votes needed for cloture next Monday at 3 PM EST.

- Bill text

- Joint Tax Committee score. (Note that this excludes the unemployment insurance, which should have a roughly $56 billion cost.)

- Staff summaries: Democratic staff (Senate Finance?), Republican Camp-Grassley memo

Assuming the Senate invokes cloture Monday afternoon, I would expect the bill to pass no later than Tuesday. It then crosses the rotunda to the House, where Speaker Pelosi has a decision to make. She has unilateral authority to decide which bills come to the floor of the House. Technically 218 House members could overrule that authority using a discharge petition, but that takes at least a month, less time than is left in this Congress.

The Speaker’s choice

Yesterday the House Democratic Caucus held a non-binding vote in which they rejected the tax deal. Speaker Pelosi issued a carefully worded statement after the meeting which reads, in part:

In the Caucus today, House Democrats supported a resolution to reject the Senate Republican tax provisions as currently written. We will continue discussions with the President and our Democratic and Republican colleagues in the days ahead to improve the proposal before it comes to the House floor for a vote.

While it’s amusing to see her describe the Obama-Reid-McConnell bill as “the Senate Republican tax provisions as currently written,” the key language is “We will continue discussions … to improve the proposal before it comes to the House floor for a vote.”

She did not say “The bill in its current form must be changed before it comes to the House floor to a vote,” nor “I will not bring this bill to the House floor for a vote in its current form.” You should be forgiven for thinking her statement meant that, but she could have said that if she had wanted to tie herself to the mast. She did not.

In legislative parlance the Speaker is about to be jammed by the Senate. Her options are (a) bring a bill to the floor that her caucus hates and watch it pass and become law; or (b) take sole responsibility for stopping the bill, almost certainly until next year.

Jamming is when you use the legislative process, often at the end of a session, to limit someone else to a yes-or-no decision in which yes is painful and no is even worse because you get blamed for killing something popular. The Speaker and House Democrats want to escape from this binary choice, to gain leverage to change the bill to their liking. Their options for generating that leverage are:

- House Democrats defeat the Senate-passed bill;

- House Democrats amend it and send it back to the Senate;

- or the Speaker refuses to bring it up for a vote.

I don’t think House Democrats could defeat this bill on a straight up-or-down vote. I expect a large number of Senate Democrats will vote aye, influenced by the President, Leader Reid, and extender tax goodies contained within the bill. A big Senate Democratic vote count makes it harder for a House Democrat to vote no. Almost all House Republicans will support it. While the average voter among House Democrats opposes this bill (as we saw from yesterday’s Caucus vote), I’m fairly certain the marginal House Democrat will be an aye.

The Speaker and House Democrats would almost certainly prefer to amend the bill and send it back to the Senate. This is in their power to do (if they can unify), but I expect that doing so would face solid Senate opposition and therefore fail. It would go something like this:

Speaker Pelosi & House Democrats to Senator Reid: We’re going to improve this bill and send it back to the Senate.

Senator Reid to Speaker Pelosi: I like your improvements. Let me check with Senate Republicans.

Senator McConnell to Senator Reid: No. We have a deal with the President and you and we’re not changing it.

Senator Reid to Speaker Pelosi: McConnell said no. My hands are tied. I made an agreement with him that I can’t break. Even if I could, there’s no way I can get a modified bill through the Senate before we adjourn. McConnell will filibuster it and it will die in the Senate. I can’t accept that.

Speaker Pelosi & House Democrats to Team Obama: Mr. President, will you help pressure Senator Reid?

Team Obama to Speaker Pelosi: We’d love to help you, really we would. <snicker> Can’t. Senator Reid is right, we can’t overcome a Republican filibuster. If we had more time there might be a way to overcome that, but we must get this done before the end of the year.

Speaker Pelosi & House Democrats: $&^$@#(@*&^!

This means that, if Speaker Pelosi and/or the majority of her caucus want to kill this bill, she’ll have to do it by refusing to bring it to the House floor. That’s an impossible position for her.

If she brings the Senate-passed bill to the floor for a vote, in her last major legislative effort as Speaker before transitioning to minority status, her caucus will split on (what they perceive as) a massive legislative defeat on a top-tier issue. When you’re a legislative party leader, your caucus splitting is very, very bad. On an issues like this it’s a disaster.

If she still refuses to bring the Senate-passed bill to the House floor, then Congress will adjourn for the year and she (not House Democrats, but she, Nancy Pelosi) will be solely responsible for rejecting the broadly bipartisan bill. She will be responsible for tax increases on all income-taxpaying Americans beginning January 1, in opposition to a bill supported by the President and Congressional Republicans.

This is what it means to be jammed. We’ll see what she does.

(photo credit: Dennis Wilkinson)

How the Left could have won on taxes

Liberal House Democrats and their outside allies are railing at President Obama for his tax deal with Congressional Republicans. This anger is misdirected. Let’s examine the President’s three basic bad options for a post-election negotiating strategy, and a fourth option that would have allowed the Left to win on taxes.

Option 1 – Cut a deal with Republicans in 2010

The key element of this strategy is “in 2010.” Negotiations occur with the outgoing Congress and while Rep. Pelosi is still Speaker.

For the President this strategy did not risk the harmful policy effects of tax increases on January 1 or the political blame that would accompany them. It clears the decks of the 2010 agenda, allowing a fresh start in the State of the Union address. Rep. Pelosi is still be Speaker during the negotiations, providing a small tactical advantage.

At the same time, by setting a deadline and explicitly avoiding a veto fight, the President gave up negotiating leverage.

Shortly after Election Day the President chose this option when he said he intended to resolve this issue in 2010. At that moment my hopes for a good outcome spiked upward.

Option 2 – Wait until 2011. Veto the Republican bill and sustain the veto. Then negotiate a deal with Republicans.

Since Democrats would still have the Senate majority, this strategy would have required Leader Reid to allow some Democratic members to vote for such a bill and to get his liberals not to filibuster it. The President would say something like, “It’s clear Republicans aren’t going to negotiate until I have proven that I will veto their bill, so let’s get that behind us.”

At least initially this strategy would have energized the Left. The veto might create more Presidential strength in subsequent negotiations with Republicans, possibly leading to a better policy outcome for Democrats. Each side would have demonstrated it can block the other’s first choice outcome (Rs through a filibuster, Ds through sustaining a veto).

But tax rates would increase on January 1, hurting workers and their families, slowing economic growth, and initiating full-fledged blame game. January 2011 would be dominated by a 2010 tax fight with an unclear outcome, rather than by the New Obama Agenda, whatever that may be.

I think the President rejected this option because he correctly calculated that Republicans would be procedurally and politically stronger in 2011. Speaker Boehner and House Republicans could pass their preferred bill and send it to the Senate, increasing their leverage in negotiations.

A weaker hand in negotiations and the policy and political damage of January 1 tax increases made this option unpalatable to the President. He said this in his bizarre press conference on Tuesday, and his aides say it in almost every press story.

Option 3 – Let taxes increase on January 1 and blame Republicans. Sit tight and wait until Republicans cave to the political pressure created on both parties by higher taxes.

This option would have been a gamble that Republicans would cave to the economic policy damage and political pressure resulting from tax increases on January 1. Both sides of the negotiation would be accepting short-term policy and political pain for potential long-term policy benefit.

A liberal House member from a safe district might calculate that this tradeoff is worth it. The President faces different incentives. He is held responsible for the national economic situation, and he would take the brunt of the blame for short-term damage caused by a stalemate.

In addition, I think Congressional Republicans convinced the President they were more willing to sit tight than he was.

Option 4 – In early 2010, pass a budget resolution conference report that creates a reconciliation bill for the President’s preferred tax policy.

Congressional Democrats had this fourth option back in the Spring of 2010. This is the partisan path that would have eliminated Republicans’ ability to block the Democrats’ preferred policy. With a simple majority of the House and Senate, Democrats could have had a complete policy win.

The budget resolution is a concurrent resolution that is not signed by the President. The failure to pass a budget resolution and create a reconciliation bill is entirely a failure of the Legislative Branch.

Even better for the Left, the budget resolution (had there been one) could have provided protected reconciliation status only for tax changes of a certain deficit size. Congressional Democratic Leaders could have precluded the additional $700 B deficit effect of the Republicans’ preferred alternative. Thus the Democratic-preferred alternative would have needed only 51 votes in the Senate, while the Republican-preferred policy would have needed 60. That’s the margin of victory.

Unlike with health care, this would have been a straight-up-the-middle use of the reconciliation process. Republican procedural complaints would have been much less effective than during health care.

There are few downsides to this option, other than the routine annual challenge of making other hard budgetary decisions needed to pass a budget resolution.

Astonishingly, this year Congressional Democrats didn’t even try to pass a budget resolution. At the time I criticized them for irresponsibility and a failure to govern. Now we see a policy ramification of this failure.

When earlier this year I asked Republican friends still on the Hill why they thought Congressional Democratic leaders didn’t choose this path, most shrugged. I would have bet heavily in their favor had they taken this route. I am happy they made this mistake, and I’m mentioning it only now, when it’s too late for them to execute it.

Assigning responsibility for the outcome

One can debate whether the President should have pursued options 2 or 3 instead of 1, but option 4 trumps all of them. The President is responsible for the strategic mistake of elevating a center-right issue to the top of the agenda in an election year, but he bears only secondary responsibility for the legislative outcome.

Speaker Pelosi, Majority Leader Reid, and their Budget and Tax Committee Chairmen are responsible for missing the opportunity last spring to choose the reconciliation path in option 4. Had they done so, the Left would have won on taxes.

Support the tax deal

Terms of the deal

Here’s what I understand the deal to be:

- Extended for two years, through December 31, 2012:

- All 2010 individual income tax rates;

- 2010 capital gains and dividend rates (15%/5%);

- Expanded Earned Income Credit is extended for two years

- Expanded child credit is extended for two years

- “American Opportunity” (education) tax credit

- Alternative Minimum Taxes as in the McConnell bill, such that no additional taxpayers face AMT

- Estate and gift taxes return, with a $5 million per person exemption and a 35% rate. After 2012 they would revert to pre-Bush levels ($1 M / 55%)

- Full expensing of business investment for all non-property investment for all businesses made between September 8, 2010 and December 31, 2011. 50% expensing for investment made in 2012.

- Extended unemployment insurance benefits are available through December 31, 2011.

- Two percent payroll tax credit for 2011 (employee side, replaces the refundable Making Work Pay credit)

- The smorgasbord of “extender” provisions will run for two years, which is retroactive for 2010 and prospectively for 2011. Details on this are still TBD and are undoubtedly occupying nearly every tax lobbyist in town. (ick)

Analysis

Given a Democratic President, this is the best possible deal that could be reasonably expected. For the next two years, through the remainder of President Obama’s first/only term, tax rates won’t go up on anyone except dead people. (OK, actually their heirs.) That is a total and complete policy win.

With almost no political effort and very little public discussion, capital tax rates aren’t going up. I had expected Congressional Republicans to get two years on all the individual rates but was nervous about the capital tax rates. That is a slightly surprising and complete policy win.

The estate & gift tax deal ends up at the Kyl/Lincoln compromise levels, as most anyone could have guessed for a while. While this isn’t a complete victory, it’s darn good.

The stupid Making Work Pay credit, which the President mislabeled as a tax cut, is now a true payroll tax cut. That’s a marginal improvement.

Unlike many Congressional Republicans, I support extending extended unemployment insurance benefits when the unemployment rate is this high. My back-of-the-envelope suggests that, at a 9.8% rate, between four and nine people who would like a job but cannot find one are getting more generous UI benefits for each person who is getting those same benefits and choosing not to take a job. I’m OK with that ratio.

If I could make two changes to the bill, I’d pay for the increased spending on unemployment insurance with spending cuts in the outyears, and I’d drop the accounting gimmick that doesn’t lower future Social Security obligations to account for the lower payroll tax revenues.

If I could make a third change, I’d drop the business expensing. This provision is a timing shift – it will cause firms to accelerate their medium-to-long-term investment spending into 2011. That’s good for 2011 growth but bad for 2013 and 2014 growth. Since I accept the consensus predictions that we’re in a multi-year slow recovery, that’s not a constructive change. There are times when this makes sense. I don’t think this is one of them, but I’m open to opposing arguments.

And while the small extenders are mostly icky special interest provisions, I’ll hold my nose on these once again, at least for now.

These are, however, relatively minor complaints. This bill is an enormous policy win because the effective changes actually go beyond 2012. Along with the actual changes to law through 2012, this bill should change your expectations of rates beyond 2012. By far the most likely legislative scenario in 2012 is that we repeat this whole scenario and go another 2-4 years without raising taxes. All the arguments that were effective in 2010 will be as effective in 2012, and Congress will already have cast this extension vote once. The tax rates, in effect, become just another “extender” vote. At the moment I’d give 4:1 odds against these rates increasing in 2013.

Compared to what?

I’ll guess that some conservatives will complain that both the rate cuts and the payroll tax cut will have only limited supply-side growth effects because they are temporary. Some may then get sloppy and say “temporary tax cuts don’t create growth.”

Yes, they do, they just don’t create as much growth as permanently lower rates. Permanently lower rates are better than lower rates for two years, but lower rates for two years are better than higher rates beginning 24 days from now.

For many higher income earners the 2% payroll tax cut reduces their average but not their marginal tax rate. I could design a package of income tax rate cuts that I’d prefer to the 2% payroll tax cut, but so what? It’s silly to compare this bill to any one person’s ideal tax policy and say it’s inadequate. This is legislating, not a theoretical tax seminar.

And isn’t letting people keep more of their wages a good idea even if for some it doesn’t have a big supply-side effect?

For those concerned with the deficit increase associated with the UI benefits, I agree that’s a problem. On the upside, the President’s Labor Day proposal to increase highway spending by $50B – $100B just became a lot less likely, as the business expensing provision with which it was packaged is being enacted here.

Recommendation

No-brainer. Support the deal.

(photo credit: FaceMePLS)

Bowles & Simpson succeeded

Much of the press coverage of Friday’s result from the President’s fiscal commission focused on the failure to get 14 of 18 votes for recommendations, the supermajority threshhold established by the President’s executive order. A commission created by executive order cannot legally bind either the President or Congress. 14 votes would have been nice, and it would have triggered a prior commitment by Senate Majority Leader Reid to bring the package to a floor vote in 2011. (Speaker Pelosi made a parallel commitment, which is now irrelevant given the party switch in the House.)

I think commission Chairman Erskine Bowles, a moderate Democrat former White House chief of staff to President Clinton, and Co-chairman Alan Simpson, a former Republican Senator from Wyoming, succeeded. Here is the final tally of support. This represents public statements rather than votes, since Bowles and Simpson never formally brought it to a vote.

The press reported the outcome as 11 for the recommendations and 7 against. This obscures the true result, which was a 4-11-3 split:

- 4 opposed the recommendations from the left:

- Sen. Max Baucus (D, Finance Committee Chairman)

- Rep. Xavier Becerra (D)

- Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D)

- Andy Stern (D, President, SEIU)

- 11 supported the recommendations:

- Chairman Erskine Bowles (D, presidential appointee)

- Senator Alan Simpson (R, presidential appointee)

- David Cote (Honeywell Chairman/CEO, presidential appointee)

- Alice Rivlin (D, presidential appointee)

- Sen. Tom Coburn (R)

- Sen. Kent Conrad (D, Budget Committee Chairman)

- Sen. Mike Crapo (R)

- Sen. Dick Durbin (D, Whip)

- Ann Fudge (former CEO, presidential appointee)

- Sen. Judd Gregg (R)

- Rep. John Spratt (D, outgoing Budget Committee Chairman)

- 3 opposed the recommendations from the right:

- Rep. Dave Camp (R, incoming Ways & Means Committee Chairman)

- Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R, incoming House Repubican Conference Chairman – #4 in leadership)

- Rep. Paul Ryan (R, incoming Budget Committee Chairman)

That, dear readers, is a genuine bipartisan coalition. It was built by two moderates, Bowles and Simpson. I use “bipartisan” rather than “centrist” because it contains not just moderates like Bowles, Simpson, Rivlin, and Cote, but conservatives like Coburn and Crapo and, quite significantly, Durbin, a liberal and #2 in the Senate leadership. The failure to get 14 votes is far outweighed by this remarkable result.

I’m not at the moment addressing the substance of their recommendations, merely the misinterpretation of the strategic consequences of the result.

All eyes should now turn to President Obama. When he created this commission in January there were two schools of thought. The first was that he was genuinely attempting to plant the seeds of a future bipartisan compromise. The second was that he was cynically trying to punt the hard fiscal policy questions past a campaign year and the midterm election.

Whatever the President’s intent back then, this result now presents both opportunity and threat for the President. I’d bet heavily he is making his strategic decision this week or next. I’ll write more about that soon.

(photo credit: The White House)

Ten tips for a practical growth agenda

National Review published a piece of mine in this week’s issue (dated November 29, 2010).

Thus Does the Economy Grow

The American people did not give power to congressional Republicans; they took it away from congressional Democrats. Republicans now have an opportunity to prove that they deserve majority status – that they can operate not just as an opposition party, but as responsible leaders who are willing to make hard choices and solve problems.

The goals of an ideal economic-growth agenda are simple and well known: a large and thriving private sector and a small government; reduced government spending, which means lower taxes (or at least not higher ones) and smaller deficits; open trade and investment; taxes and regulations that don’t distort decisions, discourage capital formation or work, or provide rents to the politically powerful; deep and flexible labor markets; a reformed financial sector that channels savings to where they can do the most good; a society in which education and innovation flourish, and the most talented people in the world want to become Americans; a stable, low-regulation legal environment, in which monetary policy is sound and business decisions issue from customers and competitors rather than regulators and judges.

Practical policymaking is about moving incrementally in the right direction rather than trying to achieve the ideal all at once. It’s easy for elected officials to distract themselves with simplistic partisan fights that are politically advantageous but either make little headway toward the goal or distract from more important underlying problems. Progress on a practical growth agenda requires recognizing the limits of policy and taking political risks.

Here, then, are ten practical tips for elected Republican officials, who are torn between trying to govern as a majority party and trying to oppose President Obama’s agenda as a minority party.

One. Prioritize medium-term problems caused by the government rather than trying to push businesses to expand more rapidly. The economic-deleveraging process is painful, slow, and necessary. Tools to mitigate the pain or accelerate the recovery have failed. So, refocus: Stop trying to mess with the economy’s natural process of rebalancing. You’re only making it worse with unintended consequences. Don’t restore the homebuyer tax credit or try to put a floor on housing prices. Instead of stimulating particular types of investment, or encouraging businesses to hire, or searching for chimerical shovel-ready projects, spend your time fixing the medium-term problems caused by flawed policies. It takes political courage to admit that the short-term economic-adjustment process will be slow and painful, but additional policy distortions will only make things worse.

The government needs to worry less about the private sector and get its own house in order. There is plenty of work to be done: cutting government spending; preventing tax increases; replacing the failed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with a competitive private market; enacting free-trade agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea; and undoing the worst regulatory excesses of the past two years.

Two. Set the right goal: creating the conditions for growth rather than trying to create growth. Policymakers need to get the policies right and let business leaders decide how to run their firms. Corporate leaders are sitting on unprecedented piles of cash, waiting to see what Washington will foul up next. Take Washington out of their decision-making by creating a stable, predictable, low-cost business environment. They will then decide how best to hire, invest, and expand. Your job as an elected official is not to create economic growth or jobs, it is to create the conditions under which the private sector creates growth and jobs. Stick to your lane and let business leaders stick to theirs.

Three. Spending is now even more important than taxes. Every dollar spent by the government comes from current or future taxes. If you focus your legislative energy on keeping current taxes low and do nothing to slow future spending growth, you merely shift taxes to the future. Without a spending-reduction plan, a “no-tax-increase” strategy is incomplete. Don’t let the president raise taxes now or ever, and develop your own credible and specific spending plan. Convince voters, taxpayers, business leaders, and investors that, if given more power, you would use it to solve our entitlement-spending problem. Paul Ryan’s “Roadmap” is a good start – federal spending should not exceed 20 percent of GDP. (I’d prefer much less.)

Four. Don’t waste all your time on nickels and dimes and process reforms; instead, slow entitlement-spending growth. Yes, it’s good to cut stimulus spending. To eliminate earmarks. To cut discretionary spending back to 2008 levels or lower, and to wage the usual Left/Right appropriations battles. These are important for restoring confidence in government, for undoing some of the worst spending excesses of the past two years, and for atoning for Republican spending sins. Such actions will be popular with many who voted to remove Democrats from power. Yet they are quantitatively insignificant in the long run.

With the retirement of the first baby boomers, the demographic wave begins to swamp us. Further delay of entitlement reform guarantees that tax increases will become part of a future solution. In Greece and France, citizens rioted because their benefits were being cut. In America, the new political force wants smaller government. Ignore the AARP’s bleats and tell the truth about Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. We must make new, more modest, sustainable promises to younger workers, who already know that the old promises are bogus.

We should raise the eligibility age for collecting full benefits to keep up with demographic changes. We should transform these programs from forced-savings vehicles into strong safety nets that protect future seniors from poverty. We should tell younger workers that they must start saving now to supplement that safety net, and that they will be responsible for a greater portion of their retirement and health-care costs than their parents and grandparents were for their own. We should apologize to these young Americans and their children for waiting so long and letting it get this bad, and we should permanently restructure these programs so that government does not expand over time.

Some Republicans will want to duck this political risk, to shirk their responsibility and instead fight about millions in outrageous earmarks rather than hundreds of billions in popular entitlement promises. Because we have waited too long to act, we must now either grasp the nettle or allow America to drift into European levels of taxation. Any congressman who rejects the Roadmap and refuses to propose a quantitatively comparable alternative is implicitly endorsing massive future tax increases. That’s irresponsible and anti-growth. The politics of this issue are hard but the decision should be easy.

Five. Tax levels and tax structure are both important, but levels are a higher priority. Republicans and conservatives love to debate the ideal tax reform. Structural reform is good, necessary, and very hard to enact. By all means push for an improved tax code, but not at the cost of higher tax levels or of failing to develop a credible long-term spending plan. A perfectly structured tax code that collects 25 percent of GDP is worse than a flawed tax code that collects 18 percent of GDP. Beware the siren call of the money-pump VAT.

Six. Don’t delink income-tax rates. The strategy we developed in 2001 and 2003 worked. Forced by reconciliation rules to sunset the tax cuts, we set them all to expire on the same day. President Bush reframed the top income-tax rates as small-business tax rates. This argument won the day in 2003 and 2010 and will win again as long as the expiration dates remain synchronized. Don’t fall for the trap of temporarily extending the top rates and permanently extending the others. This would guarantee future increases in the top rates.

Seven. Offer to help the president expand free trade and open investment. Rebuild the center-right free-trade coalition. The president will need to deliver a few Democrats to offset the protectionist Republicans (darn them). You can fight economic isolationism, raise American standards of living, help American allies in Latin America and Asia, cooperate with the president, and split congressional Democrats. That’s a five-part win.

Eight. Offer to help the president fight the teachers’ unions and improve elementary and secondary education. You agree more than you disagree with the president on education. He has shown a limited willingness to take on the teachers’ unions, and you need him to deliver Democratic votes to overcome a Senate filibuster. Encourage the president and reward him when he takes these risks. Prioritize education-reform legislation and pull him farther than he’s willing to go. Treat this as an opportunity for imperfect incremental improvements in law rather than perfect message bills that die in the Senate. Education is a long-term economic issue of paramount importance.

Nine. Now that cap-and-trade is dead, build a supermajority to stop the EPA from pretending it is a legislature, and then cut a deal. After the Copenhagen implosion and the death of a domestic economy-wide carbon price, the president cannot block the EPA from fouling up the economy without something to show for it. Offer a little more money to further subsidize carbon-reducing-technology R&D in exchange for legislatively stopping the EPA from taking over much of the economy. Its unchecked use of regulatory authority would create uncertainty and be a significant threat to future economic growth.

Ten. Lay the groundwork for repeal of the Obama health-care laws in 2013. Develop multiple alternatives. Pass repeal in the House. Pressure in-cycle Senate Democrats to take a stand, and make repeal a centerpiece of the 2012 policy debate. In doing so, stop playing the Medicare card. While the health-care legislation cuts Medicare spending in the wrong way, to prevent fiscal disaster we need even more Medicare and Medicaid cuts than were enacted in those laws. If you use Medicare to scare seniors and repeal Obamacare but, as a result, cannot address Medicare’s unsustainable spending path, you have made things worse, not better.

It will be tempting to cherry-pick the easy partisan fights from this list and postpone the politically risky elements for later. Republicans should instead treat voters like adults. Explain the mess we’re in and stress that the solutions will not be painless. Show the American people that you deserve the responsibility provisionally granted to you.

Keith Hennessey, former senior White House economic adviser to Pres. George W. Bush, blogs at KeithHennessey.com. He is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and a lecturer at Stanford Business School and Stanford Law School. This article originally appeared in the November 29, 2010, issue of National Review.

President George W. Bush’s spending record

In a blog post at the Wall Street Journal, James Freeman writes:

But George W. Bush is making a less credible claim, now that reducing federal spending is a top voter concern. Mr. Bush is currently portraying himself as a spending hawk, with a chart in his new memoir showing that federal spending averaged just 19.6% of GDP during his tenure. This appears to make Mr. Bush a more responsible spender than predecessors Bill Clinton, George H.W. Bush, and even Ronald Reagan.

Nowhere in Decision Points does President Bush refer to himself as a “spending hawk.” He does write:

Despite the costs of two recessions, the costliest natural disaster in history, and a two-front war, our fiscal record was strong.

I drew a different conclusion than Mr. Freeman did from the President’s book. Throughout Decision Points and this section in particular, I read President Bush as providing context to explain the decisions he made, rather than trying to make particular claims or classify himself.

Despite his post’s title, “George W. Bush’s Fuzzy Math,” Mr. Freeman does not dispute the math or the facts in President Bush’s book. He instead argues for a different way of measuring a President’s fiscal record.

The undisputed facts are:

- Average federal spending was a smaller share of the economy during the George W. Bush administration than during each of the Clinton, George H.W. Bush, and Reagan administrations.

- The same is true for taxes. Average federal taxes were a smaller share of the economy under our 43rd President than under our 40th, 41st, or 42nd.

- Of the four, President Clinton’s deficits were smallest, almost entirely because his revenues were highest. President George W. Bush had the second-smallest deficits of the four.

- The budget deficit during President Bush’s tenure averaged two percent, below the fifty-year average of three percent.

My conclusions: Relative to the economy, the federal government was smaller during the Bush Administration than under any of its three predecessors, and his deficits were small by historic standards.

Based on data provided by a frequent critic of the President’s, Mr. Freeman looks only at the change in the level of spending from the day the President took office to the day on which he left. He ignores baseline trends and the role of Congress and assigns full responsibility for the change between those two endpoints to the President. He uses these two points to compare President Bush unfavorably to Presidents Reagan and Clinton, because spending declined on their watches while it increased on President Bush’s.

Mr. Freeman applies President Obama’s “inherited” meme to federal spending, arguing that Presidents Reagan and Clinton deserve credit for reducing spending from even higher levels when they took office. He writes, “Even with a Democratic House, Mr. Reagan managed to cut spending as a percentage of GDP from 23 to 21.” Spending when President Reagan took office in 1981 was 21.7% of GDP. With a Democratic House and a Republican Senate, it grew to 23.5% in 1983, then declined to 21.2% in 1988. Mr. Freeman gives President Reagan credit for the decreases but no blame for the increases. Yes, spending declined over Reagan’s tenure, but by 0.5 percentage points, not by two points as Mr. Freeman suggests.

Yes, federal spending increased over President Bush’s tenure. The biggest increases were for defense and homeland security. While critics often focus on the $50 billion in increased Medicare spending for drugs in 2008, they ignore the much larger $350 billion in increased baseline Social Security and Medicare spending from 2000 to 2008. President Bush took political risks to propose specific changes to significantly slow the growth of both Social Security and Medicare spending. These proposals were largely ignored by Congress.

And yet even at its highest point during the Bush tenure, spending as a share of GDP was still lower than the lowest year of the Reagan Administration. Should we give Reagan credit for the slight decline and blame Bush for the increase, or should we say the Bush years were better because government was smaller?

Mr. Freeman’s approach broaches an interesting question: should we measure a President based only on the change between a President’s first and last days in office, or instead on the average levels over the full term, which incorporate both policy changes and the starting point for those changes, and which look at the full eight years rather than at just the endpoints? This debate should seem familiar: for 21 months President Obama has argued that his policies have made things better than they otherwise would have been, while the American people have rejected his policies because the results were inadequate. If President Obama leaves office in 2013 with unemployment at 8 percent, slightly lower than in his first full month of office, the endpoint logic suggests we should judge him an economic success because unemployment declined. I think we should instead compare the average unemployment over President Obama’s tenure with President Bush’s average of 5.3 percent and President Clinton’s average of 5.2 percent. I think that citizens care more about about average levels over time more than about the changes measured between arbitrary political endpoints.

It is also difficult to judge the “responsibility” of enacted changes objectively because observers differ on the appropriate counterfactual. The Medicare drug benefit President Bush campaigned on, proposed, and signed into law increased entitlement spending. To determine whether that is responsible or not, should we compare the increased spending to (a) no Medicare drug benefit, (b) the more expensive Democratic alternative, or (c) President Bush’s initial budget-neutral proposal, rejected privately at the time by House and Senate Republican leaders?

As we see from the ongoing debate on extending the Bush tax policies, the subjective choice of a baseline for comparison can lead to radically different conclusions about the budget effects of a proposed policy change. By choosing a helpful counterfactual, President Obama makes his proposal to extend $3.1 trillion of tax policies appear responsible and “cost free,” and argues the Republican proposal to extend $3.8 trillion of tax policies is an irresponsible “cost” of $700 billion. The numbers in Decision Points describe final levels rather than changes. President Bush thereby avoids entirely the subjective debate about counterfactuals.

I wish that we (in the Bush Administration) had been enable to convince multiple Congresses to enact more of the spending cuts proposed by President Bush. While President Bush’s critics frequently remind us of his decision to fulfill a campaign promise to add a drug benefit to Medicare, they forget or ignore his important fiscal policy moves in the other direction. President Bush vetoed the second farm bill; that veto was overridden. President Bush twice vetoed bills unnecessarily increasing spending for children’s health insurance. President Bush repeatedly proposed hundreds of billions of dollars of Medicare and Medicaid savings, only to find these proposals routinely ignored by Congress. President Bush proposed a long-term budget neutral drug benefit plus Medicare reform package to House and Senate Republican leaders in 2003. Those leaders supported the drug benefit but rejected the savings from the aggressive structural reforms. President Bush received little support for Social Security reform proposals that would have significantly addressed our long-term entitlement spending problem. If you don’t like the net spending increases during President Bush’s tenure, ask why Congress so often resisted the President’s proposals to cut spending.

Unlike each of his three predecessors, President Bush did not raise taxes.

George W. Bush, a wartime President, had a smaller federal government and lower taxes relative to the economy than each of his three predecessors, historically small deficits, no tax increases, and 5.3% average unemployment. He vetoed a farm bill and two health bills for spending too much. He proposed structural and incremental reforms to Social Security and Medicare that set up the current entitlement reform debate. Maybe the conventional wisdom should be revised a bit.

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission delays its reporting date

Here’s a press release from the commission:

To ensure that the Commission’s ongoing investigation and the documentation thereof is appropriately completed, the Commission has resolved, by majority vote, to deliver its report in January 2011, rather than on December 15, 2010. The additional time will allow the Commission to produce and disseminate a report which best serves the public interest and more fully informs the President, the Congress and the American people about the facts and causes of the crisis. The Commission will conclude its operations by February 13, 2011, as prescribed.

Here’s a statement from four commissioners, including me:

Today, Republican Commissioners on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (“FCIC”) voted against a motion to change the date of delivery of the Commission’s report to the President and Congress to January 2011. The Commission is statutorily required to deliver the report on December 15, 2010 as set forth by the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009.

The Commission has had over a year to complete the report and we believe the delivery of the report to the President and Congress is being delayed to accommodate the publication of a book-length document to coincide with the presentation of the FCIC’s findings and conclusions.

We believe a report containing the findings and conclusions of the FCIC on the causes of the financial crisis can be delivered by the statutory delivery date and Republican Commissioners are prepared to work to meet the deadline set forth in statute.

I don’t think this is an earth-shaking development but I’d like to explain my vote nonetheless. I voted no today for a simple reason: I think an aye vote would violate the law, or at a minimum would be inconsistent with the law.

Section 5(h) of Public Law 111-21 begins:

(1) REPORT. On December 15, 2010, the Commission shall submit to the President and to the Congress a report containing the findings and conclusions of the Commission on the causes of the current financial and economic crisis in the United States.

To put it simply, the Commission lacks the legal authority to change its own reporting date. Only the Congress can do that.

Chairman Angelides’ letters to the President and the Congressional leaders read, in part:

To ensure that the Commission’s ongoing investigation and the documentation thereof is appropriately completed, the Commission has resolved, by majority vote, to deliver its report in January 2011, rather than on December 15, 2010.

The Commission does not have the authority to make that decision, because it directly contradicts section 5(h)(1) of Public Law 111-21.

A reasonable argument can be made that the Commission might produce a better report if allowed more time. I wouldn’t make that argument, but it’s reasonable for someone else to do so.

The FCIC is a creation of a law, and we must be governed by that law whether we commissioners like it or not. If it’s that important to take more time, we should have asked Congress to change the statute. It’s true that Congress would almost certainly have said no, and so it may not have been worth even asking. Still, I think that should not lead us to conclude that we, as commissioners, can or should therefore vote to do something that directly contradicts the law that granted us our authority.

To me, the arguments that others have done so in similar circumstances, or that there is no penalty or legal consequence if we miss the date, are irrelevant.

I voted no because I thought doing otherwise would violate the law. I won’t do that, however insignificant or unobjectionable the consequence or reasonable the justification. Maybe I’m just old-fashioned.

(photo credit: Quinn Dombrowski)

Reactions to the President’s post-election press conference

Here are my initial reactions to important economic policy elements of the President’s press conference.

The President argued the electoral losses were the result of a continued weak economy and his inability to convince voters that he had made things better quickly enough. He repeatedly ducked the question of whether his policies contributed to the Democrats’ devastating losses. Two conclusions are consistent with ducking this question: (1) he thinks his policies did not hurt Democrats on Election Day; or (2) he knows they hurt Democrats but doesn’t want to admit it because doing so would further risk the policy gains he has achieved. I find it very hard to imagine (1), but I misjudged him last January and as a result I incorrectly concluded he would stop pushing for health care reform, so I lack confidence in my ability to discern between the two.

He did not acknowledge learning anything from the election or that he was in any way surprised by the result. In contrast he surprised me with the word “confirmed”:

And yesterday’s vote confirmed what I’ve heard from folks all across America: People are frustrated — they’re deeply frustrated — with the pace of our economic recovery and the opportunities that they hope for their children and their grandchildren.

Given this answer, I’d like to ask him “Were you surprised by Tuesday’s results?”

The initial press reaction was that the President “took responsibility for the losses.” The precise words in his prepared statement were, however, artfully phrase:

Over the last two years, we’ve made progress. But, clearly, too many Americans haven’t felt that progress yet, and they told us that yesterday. And as President, I take responsibility for that.

The President took responsibility only for “too many Americans

In a prepared statement as important as this one, no language is accidental. These sentences foreshadow his upcoming economic priorities and themes for next year’s budget and State of the Union address:

But what I think the American people are expecting, and what we owe them, is to focus on those issues that affect their jobs, their security, and their future: reducing our deficit, promoting a clean energy economy, making sure that our children are the best educated in the world, making sure that we’re making the investments in technology that will allow us to keep our competitive edge in the global economy.

and

In this century, the most important competition we face is between America and our economic competitors around the world. To win that competition, and to continue our economic leadership, we’re going to need to be strong and we’re going to need to be united.

He also tends to connect economic competitiveness with domestic infrastructure, R&D, and education spending. This linkage is not accidental.

He tried to erect a firewall around the health care laws:

And with so much at stake, what the American people don’t want from us, especially here in Washington, is to spend the next two years refighting the political battles of the last two.

Yet for several months he has been refighting (is that a word?) the tax rate battle of ten years earlier, and his entire economic message has been a backward-looking complaint and a relitigation of the policies and conditions he “inherited.”

He floated a few areas of potential bipartisan agreement:

- the looming tax increases;

- energy:

- expanding domestic natural gas supply;

- energy efficiency;

- “how we build electric cars”;

- expanding nuclear power;

- education;

- limiting appropriations earmarks;

- fixing one tax provision in the health care laws that hurts small businesses;

- infrastructure spending; and

- immediate (and temporary) expensing of business investment.

He acknowledged that legislation pricing carbon is dead for the foreseeable future. In doing so he acknowledged a well-established conventional wisdom, but it’s still significant when the President says it. His “this year” language should kill silly speculation about a lame duck Congress trying to enact cap-and-trade in 2010, and his “… or the year after” language takes cap-and-trade off the table through the remainder of this Presidential term.

I think there are a lot of Republicans that ran against the energy bill that passed in the House last year. And so it’s doubtful that you could get the votes to pass that through the House this year or next year or the year after.

He also signaled a willingness to trade legislative action on “clean energy” with dialing back (or prohibiting?) EPA from regulating greenhouse gases:

So I think it’s too early to say whether or not we can make some progress on that front. I think we can. Cap and trade was just one way of skinning the cat; it was not the only way. It was a means, not an end.” And I’m going to be looking for other means to address this problem.

And I think EPA wants help from the legislature on this. I don’t think that the desire is to somehow be protective of their powers here. I think what they want to do is make sure that the issue is being dealt with.

Finally, on the question of looming tax increases he signaled that “This is something that has to be done during the lame duck session,” and he made no negative statements about extending all the rates. When asked directly “So you’re willing to negotiate?” he replied “Absolutely.” In upcoming days I’ll write about potential paths to a tax deal.

(photo credit: The White House)

The other side of the White House white board

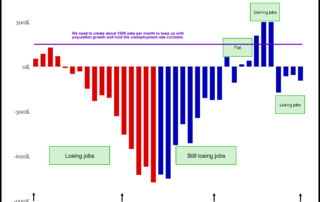

Here is my view on CEA Chairman Austan Goolsbee’s recent White House white board presentation on the U.S. employment situation. I apologize for the spotty sound quality – this is my first video and I’m just learning the techniques.

Checks for the politically powerful

Senior citizens, disabled people, and veterans have four things in common:

- we feel empathy for them;

- they are politically powerful constituencies;

- their government benefits are indexed to inflation through an annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA); and

- the President wants Congress to write them a $250 check.

Inflation was low enough over the past year that there is no automatic formula-driven COLA for next year. The dollar amount on Social Security checks, disability checks, and veterans’ benefit checks will not change next year. And yet the President proposes to write an additional $250 check to each of these more than 50 million Americans, for a total taxpayer cost of about $14-15 B.

On Friday the White House released a Statement by the Press Secretary which said in part:

Many seniors are struggling in the face of the economic downturn, having seen their savings fall. … The President will renew his call for a $250 Economic Recovery Payment to our seniors this year, as well as to veterans and people with disabilities.

I’d like to ask about other Americans, may of whom are struggling but who are not as well organized or as politically powerful as these groups.

Q1: What about a poor mom working two jobs? What about a 20-year old who can’t find a job? What about a recently laid off 58-year old factory worker who is underwater on his mortgage? They are struggling too. Why does the President think that 50+ million seniors, disabled people, and veterans are struggling more than millions of others like these people?

Q2: What about the two-income family of four making $80K or $120K? Why is it fair to make them pay higher taxes (now or in the future) to write a check to someone else when the cost of living did not increase?

The political justification for this policy is clear. The policy rationale is not.

(photo credit: Steven Martin)