A different strategy for impatient fiscal conservatives

Several conservative House and Senate Members, dissatisfied both with the spending cuts enacted so far and with repeated short-term appropriations negotiations, are threatening to oppose another Continuing Resolution. I think that’s a mistake.

Conservatives are expressing two concerns – spending cuts are not being enacted quickly enough, and short-term CRs lack funding limitations (e.g., No federal funds may be appropriated for

I support cutting spending even more deeply than the original House-passed bill. I support and place a high priority on stopping implementation of ObamaCare and the new EPA regulatory authorities. Yet I think this move is a short-sighted and even counterproductive tactical blunder.

Legislating is a team sport. You win when you can build a coalition to achieve your goals. Right now, the spending cut team is winning. Anyone who wants to change strategy or torpedo it through individual action should step up and explain not just their own threatened no vote, but how that threat will lead to a better policy outcome.

From where I sit the current negotiating environment looks like this:

- Moderate and Appropriator Republicans are generally staying quiet, allowing fiscal conservatives to shape a unified Republican negotiating position.

- Congressional Democrats are divided and in disarray.

- White House party leadership is weak. The Presidential bully pulpit is largely inactive on this issue as the President tries to keep himself “above the fray.”

- Team Obama and Congressional Democrats appear to be more afraid of a short-term shutdown than are Republicans. This gives Republican leaders leverage in the repeated short-term negotiations.

- House Republicans write the language for each Continuing Resolution and thereby control the choice presented to the Senate.

- Senate Republicans, led by Leader McConnell, have so far supported the House position. This forces Senate Democrats and the White House to choose between the House-passed bill and a shutdown. This Boehner-McConnell teamwork creates enormous leverage for fiscal conservatives.

- In addition to repeated short-term CR negotiations, there are at least two more opportunities to pursue additional spending cuts this year, on an upcoming debt limit extension and this fall during the FY12 appropriations negotiations. Twelve individual appropriations bills also provide countless opportunities for funding limitations on bad policies.

- Public opinion seems to support Republican efforts to cut spending without shutting down the government.

- Tragic ongoing events in Japan and Libya have pushed this spending battle low on the public radar.

This is pretty much the ideal environment in which to incrementally cut spending. The repeated-short-term-CR strategy is working to enact $2 B of savings per week. The strategy is not, however, resulting in any funding limitations on hot button Administration policies.

Let’s assume you’re a conservative Member who wants to do even more. You either want deeper cuts, or to enact them all now, or to enact a funding limitation rider. You threaten to oppose the next CR. Is your threat principled or strategic?

A principled position sounds like this: “I cannot in good conscience support a bill that [spends this much / funds bad program X.]” A strategic position sounds like this: “I hope that my no vote means no CR will pass. The resulting government shutdown will strengthen the hands of spending cutters in the longer-term negotiations.”

The principled argument sounds great to outside allies. But if it is not paired with a viable strategy, it is individually rewarding but likely to be counterproductive. Is it a good outcome if your principled no vote leads to a legislative result that spends more? You’ll feel better for having voted no, but the Nation will be worse off. If you don’t like your team’s strategy, try to change it.

If your vote is strategic, then please explain how you expect to win a public shutdown fight, and how that public battle will strengthen your leaders’ hand in negotiations with Leader Reid and Team Obama. Does your strategy rely on Republican message unity during the shutdown, or is it OK if now-unified Republicans split? Should a shutdown be accompanied by a public message of “We regret that Democratic refusal to cut spending has forced the government to shut down,” or instead “We shut down the government and it’s not that bad?”

Conservative Members who simply say what they individually won’t do (vote for the next CR), should explain what they want their party leaders to do in response. As an outside supporter of deep spending cuts, I care less about your individual vote than I do about the policy outcome. How will your threatened no vote lead to less government spending than the current strategy?

It is possible to develop such a strategy, but I think it’s quite difficult to make a convincing case that such a new strategy is likely to lead to a better outcome than the incremental path now being followed. If I’m wrong, then let’s hear it. Propose the alternate strategy and explain how it can succeed. My objection is not to a bad strategy, but to the apparent absence of any strategy.

Instead of threatening to oppose the next CR no matter what, impatient fiscal conservatives should demand that their party leaders ratchet up the the spending cuts in the next CR. Spending cuttters, pull the Republican team in your direction. Demand $3B of spending cuts per week rather than $2B. If policy-specific funding limitations are a priority, choose one funding limitation and insist that it be included in the next CR. (I’d choose the EPA regs, which tend to unify Republicans and split Democrats.) Use House Republican control of the legislative text to put the President and Leader Reid in the position where they have to choose between a little more savings and shutting down the government. It’s hard for them to explain why $2B of savings per week is OK, but $3B per week is the end of the world. Use that to your advantage.

For decades those who favor bigger government have succeeded incrementally, by patiently layering one new program on top of another, and by pocketing incremental spending increases that build up over time. Over the next six months spending cutters are now perfectly positioned to do this in reverse.

When you’re making steady progress toward your goal by repeating the same tactical move, when your opponents have not yet figured out how to counter that move, and when you don’t have a complete and viable alternative strategy, don’t change tactics. Just ratchet up your demands a little.

(photo credit: thirtyfootscrew)

Bad cop, worse cop

Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell are effectively maximizing their leverage in the ongoing appropriations negotiation.

Republicans did good work over the past month emphasizing that they don’t want the government to shut down. In doing so they created a political and press contrast with the chest-thumping Republicans of the 1995 shutdown.

- 1995 Republicans: “We’re going to shut down the government and like it!”

- 2011 Republican leaders: “We don’t want the government to shut down, but if Democrats continue to demand too much spending, we regret that it may be unavoidable.”

If negotiations implode, blame for a shutdown would be more evenly allocated than it was in 1995. This communications foundation means Republican negotiators have less reason to fear political catastrophe if negotiations fail, and they can therefore demand more on substance.

The two dimensions of these FY11 appropriations negotiations are money and duration. Both sides want a long duration (seven months, through the end of this fiscal year) if they get their way on money. Republican leaders place less of a priority on a full-year extension, so they can drive for a better deal on the spending level. If the Administration and Democrats insist on a seven-month bill, Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell can make them pay for it. Another short-term CR is painful for both sides, but apparently more so for Democrats. This gives Republicans leverage. Recent press coverage suggests that another short-term CR is quite possible.

Rather than good cop, bad cop, Republican Leaders are playing bad cop, worse cop with their Members. Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell are together the bad cop. On both substance and tone they have positioned themselves with the aggressive spending cutters in their party. At the same time, they can privately tell the Democratic negotiators, “You think we’re bad? You should see our freshman. They’re nuts. We’re not sure we can deliver them for anything short of the House-passed bill.” While Boehner and McConnell are the bad cop, the freshman / Tea Party / conservative rank-and-file Republicans are the worse cop. The worse cop’s threat to walk away from a bad deal appears highly credible. The Republican Leaders’ weakness at delivering votes for a weak bill becomes negotiating strength. In contrast, we know that if the President supports a deal, he can deliver a significant fraction of the Democratic party to vote for it. This Presidential vote-delivering strength weakens Democratic negotiators.

Congressional Republicans appear remarkably unified, reinforced by a surprising show of House-Senate unity in yesterday’s Senate floor votes. I cannot remember a time in the past sixteen years when House and Senate Republican leaders worked as well together as they have over the past few months. This is led by Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell, but applied to both leadership teams.

In contrast, Democrats are all over the map. Minority Leader Pelosi voted against the short-term CR while Minority Whip Hoyer voted for it. Nine Senate Democrats have loudly positioned themselves to the right of the President and their party leaders, voting against their party’s proposal yesterday. Senate Majority Leader Reid gave an impassioned defense of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada as an example of an important federally-funded priority that should not be cut.

Team Obama overreached last week when they tried and failed to anchor negotiations at the President’s request spending level with their bogus “We’ve come halfway” claim. When CBS News calls the President’s budget message “the White House’s fuzzy math” and the Washington Post gives the Administration “three Pinocchios,” you know this tactic has failed. Administration officials insist that another short-term CR would be disastrous. Yet with 10 days left before the deadline, the President’s negotiating lead (VP Biden) “spent most of” Tuesday celebrating International Women’s Day in Finland. HIs contribution to the negotiations was placing calls to Boehner and McConnell from Russian President Medvedev’s dacha. Another short-term CR looks increasingly likely, not because negotiations have failed, but because they haven’t really gotten started. I hope some high-level phone calls or private meetings are occurring, because there are no visible signs of serious negotiations.

I chuckle every time I hear Democratic Congressional leaders argue that another short-term continuing resolution would be irresponsible. This entire negotiation exists only because last year a Democratic-majority House and Senate didn’t even try to pass a budget resolution, nor any of the 12 appropriations bills. Had Speaker Pelosi and Leader Reid done their job last year, spending in FY11 would have been long resolved at a level closer to the President’s request, and Congress would now be fighting over next year’s spending levels as they should be. The same was true for taxes last year.

Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell do not have infinite leverage, and they will be attacked from their wing no matter the final outcome. So far they deserve praise for their tactical acumen in this negotiation.

(photo credit: Scott Davidson)

Looking at the Senate spending votes

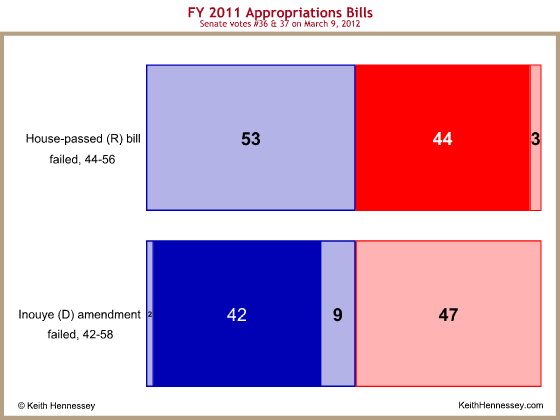

Yesterday the Senate voted on competing proposals for discretionary spending for the remaining seven months of Fiscal Year 2011.

Republicans offered the House-passed bill, H.R. 1. Democratic leaders supported an alternative offered by Appropriations Committee Chairman Daniel Inouye.

Each proposal needed 60 votes to succeed. Both failed to get even a majority.

Here I show these two votes, with Senate Democrats (and the two Independents who caucus with Democrats) in blue and Senate Republicans in red. Heavy solid coloring represents an aye vote, while lightly shaded coloring represents a no vote. As always, you can click on a graph to see a larger version.

It is politically significant that, in a 53-47 Democratic Senate, the House-passed bill garnered more votes than the Senate Democratic alternative. That is a bad outcome for the Senate majority party.

On the House-passed bill, I have positioned the three no votes on the far right. It is clear that Republican Senators DeMint (SC), Lee (UT), and Paul (KY) voted no because they want even less spending than in H.R. 1, or at least to signal that they don’t want spending to increase above H.R. 1. On this issue the three of them are the right flank in the Senate

With the exception of those three, the vote on H.R. 1 was straight party line. I am pleasantly surprised that Republican moderates supported H.R. 1. House and Senate Republicans are at the moment united.

The Democratic alternative was an implementation of the President’s proposal. All 47 Republicans voted no, while Democrats split into three camps.

The bulk of the Democratic caucus, 42 members, supported Inouye.

Senators Levin (MI) and Sanders (I-VT) voted no on the left. I presume they thought the cuts in Inouye were too deep, or at least they were casting a symbolic vote that they didn’t want cuts to go deeper.

More interesting are the nine Democrats who voted no and are making public statements that I think position them right of Inouye. This group includes Senators Bennet (CO), Hagan (NC), Kohl (WI), Manchin (WV), McCaskill (MO), Bill Nelson (FL), Ben Nelson (NE), Mark Udall (CO), and Webb (VA).

The above pictures shows a stalemate. Without a deal between the leaders, each would struggle to get a simple majority, never mind the 60 votes needed for a victory. This may explain Senator McConnell’s quote this morning:

We’re waiting for the president of the United States. He is the most prominent Democrat in America — only his signature can make something a law. Now is the time to engage, and he has been curiously passive up to this point.

So far Senate Republicans are standing firm with their House colleagues, and Senate Democrats are splitting quite significantly. And while the Senate floor is, at the moment, the battleground, this is not just a Senate game. A hypothetical Senate deal could easily fail in the more partisan House, where both the average and marginal Republican votes are farther right. Since the Speaker unilaterally controls whether a bill can be considered on the House floor, the President and his team must gain Speaker Boehner’s support for any deal.

Late last week I predicted a final spending level at the midpoint of these two bills, but said it was quite possible there will be another CR before any final deal. Today I renew both parts of that prediction, with even a little more optimism that a final spending level will favor the House bill.

Whoops

Having totally fouled up the back end of this blog, I am now in the process of restoring it after a complete from-scratch reinstall. Arrgh.

I think I have fixed most of the big stuff, but please don’t be surprised if there are some glitches over the next few days. In particular, I lost a bunch of comments (157, to be precise) that I have yet to figure out how to restore. Also, I’m still restoring pictures and graphs to some posts.

Please bear with me.

(photo credit: Dario Villanueva)

What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR)?

Yesterday Meet the Press host David Gregory asked White House Chief of Staff Bill Daley if the President was considering releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR):

MR. GREGORY: But what about the shorter term? Does the president—there’s calls to tap the strategic petroleum reserve, which comes up during these spikes. Is the president considering doing something that can arrest that spike?

MR. DALEY: Well, we’re looking at the options. There’s—there—the spike—the, the issue of, of, of the reserves is one we’re considering. It is something that only is done—has been done in very rare occasions. There’s a bunch of factors that have to be looked at, and it is just not the price. Again, the uncertainty—I think there’s no one who doubts that the uncertainty in the Middle East right now has caused this tremendous increase in the last number of weeks.

MR. GREGORY: But it’s on the table, which I think is the significant development.

MR. DALEY: Well, I think all consider—all matters have to be on the table when you go through—when you see the difficulty coming out of this economic crisis we’re in and the fragility of it.

Let’s look at the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and the President’s option to release oil from it.

What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

The SPR is a bunch of holes in the ground. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve is a collection of salt caverns at four locations in Louisiana and Texas along the Gulf Coast. Those salt caverns hold 727 million barrels of oil, managed by the Department of Energy.

The SPR is a national insurance policy. Specifically, it insures the U.S. against a severe oil supply disruption. Without this insurance, our economy could be even more sensitive to a big oil supply shock than it already is.

Created in 1975 after the Arab oil embargo, the SPR is designed to be an emergency reserve. If Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez suddenly were to decide he is no longer going to sell oil to the U.S., we would face a short-term supply disruption while we waited for supplies to arrive from other producer nations. President Bush (41) released oil from the SPR when Operation Desert Storm began in January 1991, in anticipation of supply disruptions in the Middle East. When Hurricane Katrina damaged much of the Gulf of Mexico oil infrastructure, we suddenly lost about 25% of domestic production and President Bush (43) released oil from the SPR. If terrorists were to blow up major elements of the global or domestic oil supply chain, that could cause a severe supply disruption. The SPR is not a backup supply to be used frequently when gasoline gets expensive, it’s an emergency strategic supply to be used only in a crisis.

Releasing oil from the SPR is a Presidential decision, based principally on the advice of the Secretary of Energy. The President’s White House economic and national security advisors are usually involved in the decision as well.

The U.S. relies more heavily on government stocks than private reserves. The same is true for the Japanese. The Europeans rely more on privately held commercial stocks. Since their governments don’t own that oil, the Europeans mandate that commercial storage facilities hold a certain amount of emergency reserves. Also, you can’t drain your stocks down to zero; you have to leave some oil in the tanks and especially the pipes to make the hydraulics work.

The U.S., Japan, and Germany have the biggest reserves. Then there are the Chinese, who so far have not been full participants in the international coordination system run by the International Energy Agency (IEA). Reserve withdrawals are more effective when they are coordinated among the countries with the largest reserves.

The U.S. government fills the SPR in two ways. They buy oil on the open market, and they receive oil as payments in kind for drilling leases granted by the government (called Royalty-in-Kind).

How big is the SPR?

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve can hold 727 million barrels of oil. At the moment it’s full, at 726.6 million barrels.

Here are some figures for comparison:

- The global oil market is about 86 million barrels per day (bpd).

- The U.S. consumes about 19-20 million bpd of oil and petroleum products. We import about half that.

- The Desert Storm SPR release totaled 21 million barrels.

- The Katrina SPR release coincidentally also totaled 21 million barrels.

- There are 42 gallons of oil in a barrel.

- A barrel of oil results in about 44 gallons of products, including about 19 gallons of gasoline, 10 gallons of diesel, 4 gallons of jet fuel, and 11ish gallons of other stuff. This means you get a gallon of gasoline from about 2.1 gallons of oil.

As the economy grows, any fixed-size SPR gets effectively smaller. Insurance is measured in “days of import protection”: take the average number of barrels per day that we import, and divide it into the oil we have, and that’s how many days of import protection we have.

The U.S. imports (net) about 10-11 million barrels of oil each day. At the moment the SPR is full: there are 726.6 million barrels of oil stored in these salt caverns. Divide 726.6 M by 10-11 M and you get 66-73 days.

Since you won’t replace lost imports barrel-for-barrel, the number is more of a relative than an absolute measure of how much your insurance is worth. A significant SPR release might be 100,000 bpd.

We don’t worry about losing all of our imports simultaneously. Almost one-quarter of our imports come from Canada. Our next biggest suppliers are Venezuela (11%), Saudi Arabia (10%), Mexico (9%), and Nigeria (8%). There are risks to each of these (much less so for Canada and Mexico).

A 2005 law requires the SPR to be increased to 1 billion barrels. President Bush (43) proposed doubling the current SPR to 1.5 billion barrels and increasing the size of our insurance policy. Congress has not provided significant funding for either expansion.

When should the President release oil from the SPR?

The Saudis are the first line of defense when there is a disruption in global supply. If that worries you, then figure out ways to use less oil, because the Saudis will always have the largest and lowest cost marginal supply in the world. The Saudis often/usually have spare production capacity that they hold in reserve. They appear to have dialed up their production in recent weeks, offsetting most of the recently lost production in Libya.

The phrase severe supply disruption is the key to the President’s decision about an SPR release. Oil is expensive right now for four reasons:

- Fundamentals — The global economy is recovering and demanding more oil. Global supply and demand are tight.

- Some Libyan supply has recently gone offline – maybe 850K – 1M bpd.

- Oil market participants are worried that events in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Bahrain could spread to other oil-producing nations in the Middle East and North Africa, further disrupting supply.

- Nobody is quite sure how much unused capacity the Saudis have available.

It’s hard to conclusively tease out the price effects of each factor, but policymakers need to try. High gasoline prices alone are insufficient to justify an SPR release. You have to look at why prices are increasing. One expert recently surmised that about $100 of the current $115/barrel world price (Brent) results from tight fundamentals, and the other $15-ish is from actual and feared supply disruptions.

If global economic growth accelerates (oh please oh please), then global demand will increase and the price of oil will continue to climb. That’s unfortunate and a medium-term economic problem. It’s not a reason to tap the strategic reserve.

If supplies are further disrupted, for instance by geopolitical events, then that is a viable reason for an SPR release, if the President thinks it is severe enough to justify tapping our emergency reserve.

You also shouldn’t expect an SPR release to have a huge effect on the pump price of gasoline. With oil around $100/barrel, if the President were to release 100,000 b/d from the SPR, that would probably lower the price of oil by about $2/barrel initially. That’s about ten cents per gallon of gasoline, maybe a bit more if the release were coordinated with other nations and reduced the fear premium in global oil markets. The effect would wear off over time as markets adjust to the increased supply.

Should President Obama release oil from the SPR now?

Mr. Gregory asked Chief of Staff Daley if the President is considering releasing the SPR because the price of gasoline has spiked. He further asked if the President is “considering doing something to arrest that spike.”

The President should consider a release only if he determines there’s a severe supply disruption, not just because the price of gasoline has increased. And if he does approve a release, it will not “arrest” the price increase at the pump.

The U.S. imports almost no oil directly from Libya – they supply about 0.6% of all our imports. Most Libyan oil goes to Europe, and some to China. Still, it’s best to think of oil as if it were a single big global pool. If more Libyan production were to go offline, prices in Europe would jump. Oil tankers in the Atlantic headed west for the U.S. might turn around and head east seeking out those higher prices, causing prices to rise in the U.S. (The reverse happened after Hurricane Katrina – tankers headed for Europe turned around and headed for the Southeastern U.S. after prices jumped from lost Gulf of Mexico supply.)

So far it appears the Saudis are mitigating much of the lost Libyan production. Based on public information, I think it’s hard to justify an SPR release now. If a lot more supply goes offline (in Libya or elsewhere), and if the Saudis lack the spare capacity to offset that additional loss, then the President will have a tough call to make.

(photo credit: Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy)

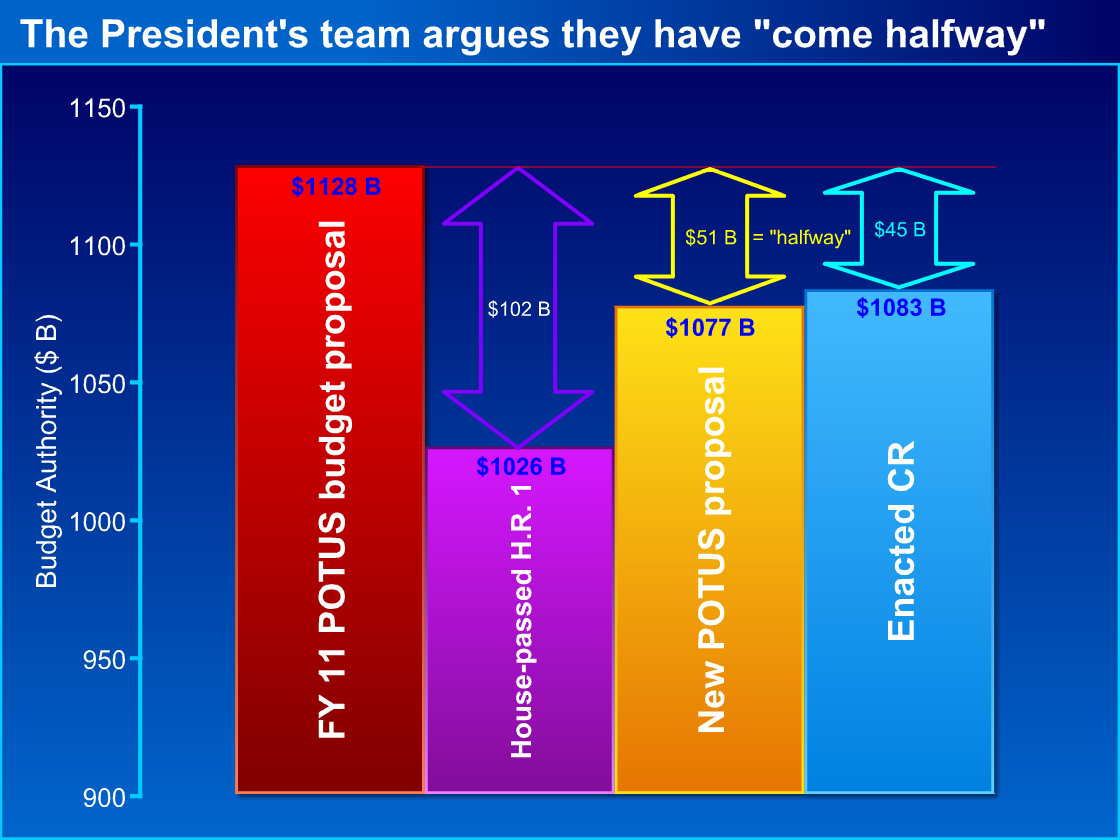

When halfway isn’t

The negotiations on the continuing resolution (CR) began yesterday. The Administration’s new line, echoed by Congressional Democrats, is that their new offer “comes halfway.”

As the players jockey for position they will be throwing out all kinds of confusing numbers. The confusion arises from two factors:

- Most of the debate centers around “deltas” rather than levels: the players are talking about the size of proposed cuts rather than the resulting absolute levels.

- The size of a cut depends upon your choice of starting point. The players are choosing different starting points from which to measure their deltas.

We can eliminate most of this confusion by focusing on proposed spending levels rather than the proposed changes in those levels.

Yesterday President Obama’s new NEC Director, Gene Sperling, presented the Administration’s perspective on the negotiations. It’s clear the mantra is “With this proposal we have come halfway.” I expect the President will start saying this soon.

Update: Here’s the President in Saturday’s Weekly Radio Address:

My administration has already put forward specific cuts that meet congressional Republicans halfway. And I’m prepared to do more.

This is called anchoring – trying to frame the negotiations quantitatively to make your own position seem reasonable, and your negotiating partner’s position seem less reasonable. It appears that neither Congressional Republicans nor the press are buying the Administration’s anchoring.

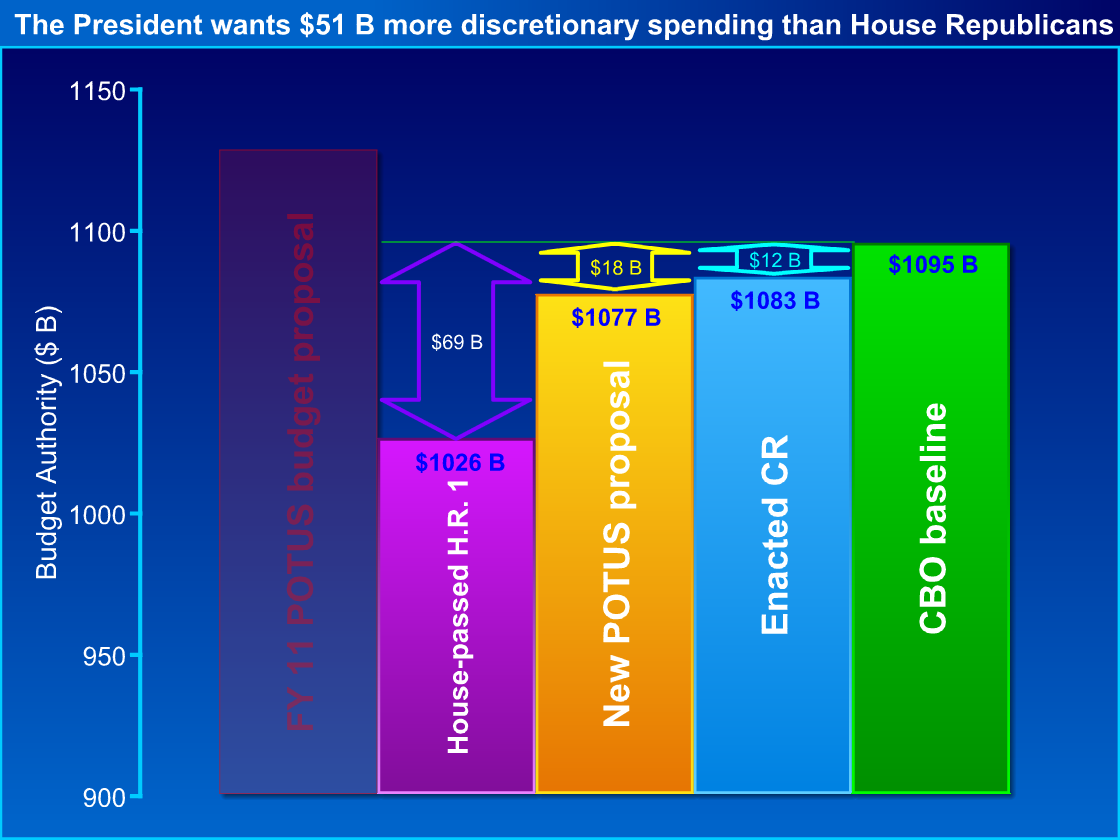

Here is how the Administration justifies the claim that they have “come halfway” with their new proposal. As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

<a href=”https://www.keithhennessey.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/cr-obama-view1.png” target=”_blank” rel=”shadowbox

- The Administration uses a figure of $1,128 B (the red bar) for the President’s budget proposal.

- They are comparing that level to the $1,026 B bill passed by House Republicans (H.R. 1, in purple) on a nearly party-line vote.

- The Administration says they have a new proposal (the yellow bar) of $1,077 B. They get to this number by taking the newly enacted short-term Continuing Resolution (the blue bar), which would lead to $1,083 B of spending if it were extended through the end of this fiscal year on September 30th. They then (say they will) propose another $6.5 B of cuts relative to this enacted law, bringing them down to $1,077 B.

- They define the negotiating space as the $102 B (purple arrow) between the President’s proposal (red) and the House-passed “Republican” bill (purple).

- They define the distance they have “moved” as the $51 B (yellow arrow) between the President’s proposal (red) and the President’s new proposal (yellow).

- $51 B is half of $102 B, therefore they have “come halfway.”

The principal problem with this presentation is that the President chose the height of the red bar. Everyone understands this is therefore an arbitrary basis for comparison. Had the President instead initially proposed $1,230 B (a number I made up by adding another $102 B to the $1,128 B shown here), he could then have described his new yellow bar as “coming three-fourths of the way.”

Democrats are struggling to convince the press that the red bar is a meaningful starting point. They correctly point out that, last fall, when selling their “cut spending by $100 B” campaign platform, Congressional Republicans used the red bar for comparison. That was a mistake when Republicans did it last fall. In recent days Republicans have admitted this mistake and are now attacking the red bar and the Administration’s “halfway” claim.

Team Obama is savvy enough to understand that they won’t convince any Republicans with this argument. They are instead trying to frame the public debate. I expect this tactic to fail within the negotiating room and mostly fail outside it.

There are other issues with that $1,128 B figure that the Administration says represents the basis for comparison. You don’t have to worry about these details, but I include them for completeness, and to further demonstrate how shaky it is to compare other levels to the red bar.

- It’s out of date. That’s what the President proposed 13 months ago. One month ago he proposed $1115 B, or $13 B less.

- Pushing the other way, it is artificially low by $23 B. The President wanted to change the way Pell grants (student loans) are measured. Congress ignored him and the effect of this is $23 B higher discretionary spending for the President’s policies.

- CBO and OMB score things differently. The $1,128 B figure is OMB, the others are CBO. In this case the difference matters.

Now let’s look at a different way to frame it.

I have faded the (misleading, in my view) President’s red bar so that we can ignore it here. I added a new green bar, showing what would be spent if Congress just did a straight extension of last year.

You can see from this graph that the House-passed bill, the President’s new proposal, and the recently enacted two-week CR all cut spending below CBO’s baseline. In my view, comparing to this green baseline is a fairer comparison than to the President’s proposal. On this basis, the President’s new $18 B in cuts from CBO’s baseline are only one-quarter (26%) of the way between baseline and the House-passed bill. This is, I imagine, how a fiscally conservative Republican in Congress would frame it.

The selection of endpoints for calculating the “gap” and how far one side has “moved” is ultimately a judgment call and at least somewhat arbitrary. I don’t blame the Administration for choosing a high bar to make themselves appear reasonable. I do blame any reporters who unquestionably report the statement “we’ve come halfway” as fact.

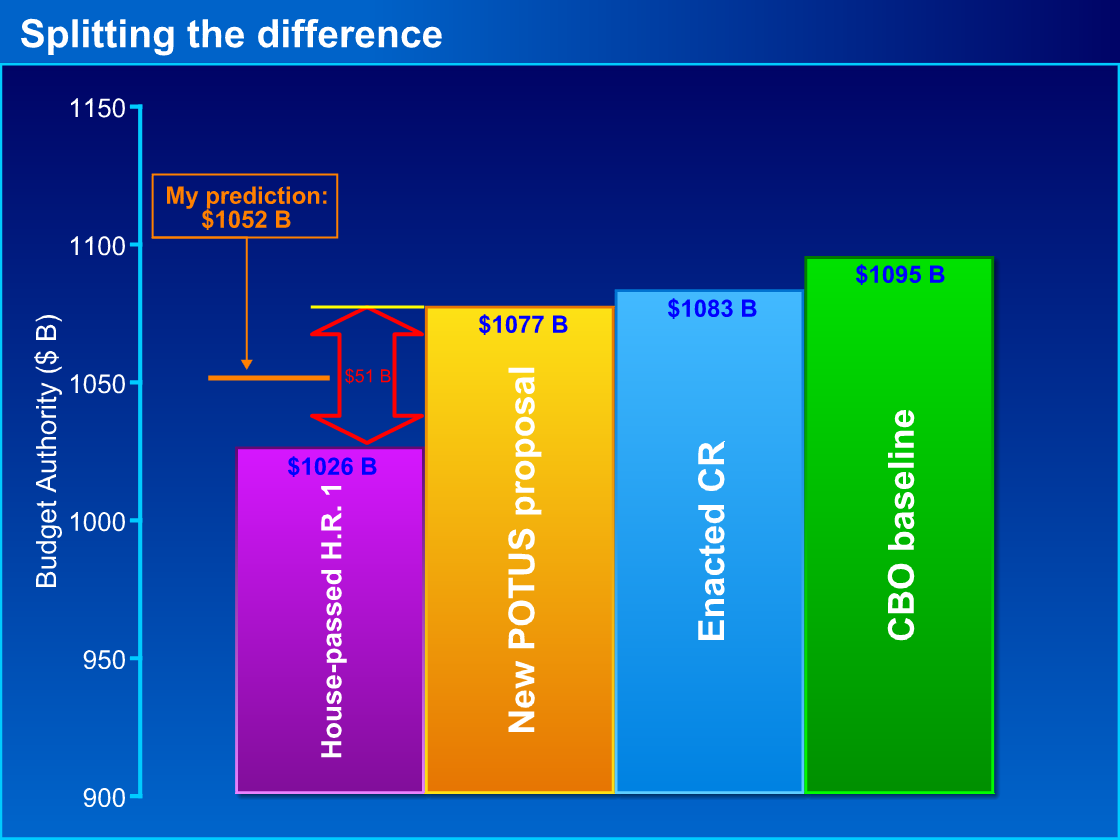

I am for the lowest possible spending – I’d be happy to support the purple bar or even lower. But rather than argue what the spending should be or how the debate should be framed, I’ll offer my prediction of what the final result will be.

I predict a final enacted (non-emergency) discretionary spending level of $1,052 B, halfway between the House-passed H.R. 1 and the President’s new proposal. I base this prediction on where I am guessing the votes are, rather than on either side’s intellectual justifications or public framing of the negotiation.

My logic is simple. The House has already passed the purple bar but cannot get that level through a Democratic-majority Senate. I think Senate Democrats will show next week that they have a majority to pass the President’s new yellow bar proposal, but will be unable to get 60 votes to overcome a Republican filibuster and, even if they could, would be blocked by the House. In both cases I see the President as backing up the Senate Democratic legislative strength, but his veto is really a fallback rather than the primary line of defense for the side that wants to spend more.

I am making a judgment that this is rough parity in terms of legislative strength. I assume both sides are equally obstinate/principled and equally skilled at negotiations, even though Democrats have repeatedly fumbled the ball over the past few weeks. I then predict the midpoint of those two equal-strength positions as the final outcome. That’s the midpoint of $1,026 B and $1,077 B, or $1051.5 B. Round up because appropriators control the paper.

It may be asking too much to imagine either side getting to this level in the next two weeks, so I won’t necessarily predict that this outcome will be achieved before the current CR expires.

Conclusions

- The Administration’s argument that “we have come halfway” is nothing more than a negotiating tactic.

- The intellectual basis for this argument is quite weak and borders on silly.

- Any framing of this debate by measuring “cuts” is dicey because the choice of a starting point is arbitrary.

- The final legislative outcome will be determined by legislative strength much more than by either side’s public framing of the numbers.

- I predict a final enacted non-emergency discretionary spending level of $1,052 B.

The President’s proposed deficits and “primary balance”

Today we’ll look at President Obama’s proposed deficit path, as yesterday we looked at his spending and revenue paths.

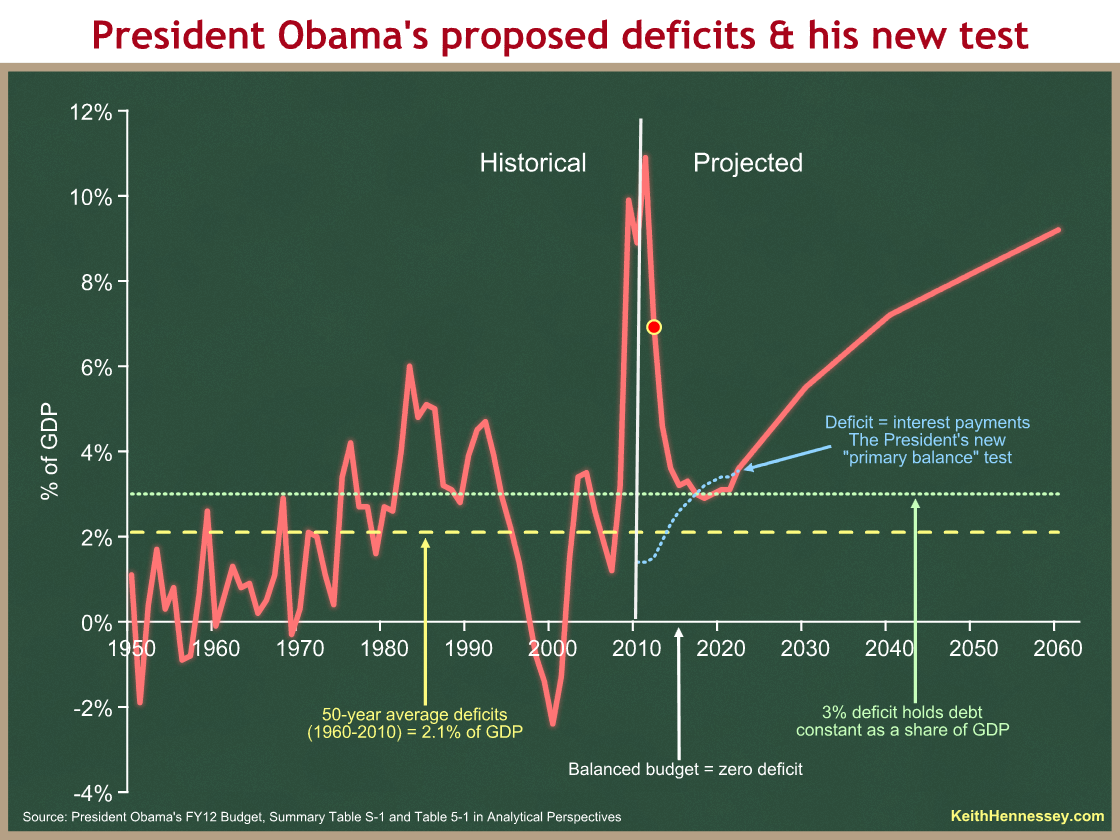

The red line on this graph compares the last 50 years of deficits with the next 50 years under President Obama’s proposed policies.

The vertical white line at 2011 separates the past from the projected future.

This graph is busy because we have four different bases for comparison. The first three are standard metrics.

- The white x-axis would be a balanced budget.

- The dotted yellow line shows the 2.1 percent of GDP average deficit over the past 50 years.

- The dotted green line is at 3 percent. Above the dotted green line, debt will grow faster than our ability to pay it.

- The dotted blue line is the President’s proposed new test for himself and the country. He now defines success as getting red below dotted blue.

The President proposes a 7 percent budget deficit for 2012 (the red dot). His deficits would bottom out at 2.9% seven years from now, in 2018, and then rise steadily forever.

The President proposes deficits that are in each year well above the historic average (dotted yellow line).

Until 2015, our debt/GDP ratio will increase every year. For a few years beginning in 2015, the President’s budget would stabilize debt as a share of the economy.

You can see our severe problem in the large, sustained deficits that are projected to grow forever, beginning a few years from now. We used to call this a long term problem.

Current short term deficits are high enough to be economically damaging. That long term deficit path is unsustainable. Something will break.

The President’s budget doesn’t even pretend to shoot for balance, or to reduce deficits to the historic average. He has abandoned those goals, and instead draws a new dotted blue line that grows rapidly over time, and then defines success as getting deficits below that.

Here is the President in a press conference Tuesday.

Our budget … puts us on a path to pay for what we spend by the middle of the decade.

… by the middle of this decade our annual spending will match our annual revenues. We will not be adding more to the national debt. So, to use a — sort of an analogy that families are familiar with, we’re not going to be running up the credit card any more.

I will deal with the “not adding more to the national debt” line tomorrow. Today I want to focus on “pay for what we spend” and “our annual spending will match our annual revenues.”

The President’s credit card analogy is a good one. Anyone with a mortgage or a credit card balance knows that you have to make monthly interest payments. Those interest payments don’t get you any new stuff, they just pay for the past borrowing you have done. (Technically, they are paying for the service of the loan you have been provided.) If you stop using your credit card, you still have to make interest payments on your outstanding balance. In the same way, a portion of your monthly mortgage payment is interest on the loan you used to buy your house.

The same is true for the government. In 2012, $240 billion of next year’s $3.7 trillion of federal spending is for interest payments on accumulated federal debt. The President wants to take that amount out of the deficit calculation, and define success as paying only for new spending. He wants to ignore interest payments when calculating the deficit.

Keith Koffler puts it well: “So as a practical matter, what he is offering is totally meaningless. If I could stop paying interest on my mortgage, I’d be on a plane to Paris tomorrow.”

The President is trying to politically redefine deficit to mean only the gap between the red and dotted blue lines, rather than the gap between the red line and the x-axis. Once he gets red down to dotted blue, he would say he has balanced the primary budget, meaning that all revenues in that year will equal all spending except interest payments.

Boring interest payments don’t pay for fun new high speed choo choos, but we still have to make them. In 2017, the Treasury would still have to borrow $627 billion from financial markets just to raise the cash to make interest payments.

Our unified deficit would still be 3% of GDP. Our $627 billion unified deficit would still exceed the historic average of 2.1% of GDP.

I had originally thought the President was just trying to lower the bar, to obfuscate his proposed enormous deficits by trying to redefine the word “deficit” in a way that few would understand. Now I worry about a deeper rationale.

Maybe the President actually thinks it’s not his job to make the hard choices to pay for the interest costs of debt accumulated before he took office. Is he arguing that his job is not to solve the challenges our Nation faces, but instead only to get to a point (seven years from now) where his actions don’t make things even worse?

I had always thought his “inherited” meme was simply a political tactic – blame your predecessor for everything bad so you look good in comparison. That’s tawdry but hey, politics can be a rough game.

Now I worry that he might actually believe it. Our accumulated debt is now 62% of one year’s GDP, up from about 40% when the President took office. By defining primary balance as his goal, is President Obama saying that he’s not responsible for proposing policies to pay for the interest costs on that debt, one third of which was accumulated on his watch?

I find myself hoping that he is instead simply trying to confuse us and hide the bad news in his budget. The alternative is even more frightening.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

The long term budget problem begins now

Let’s look at President Obama’s proposed long run budget path. Click the graph to see a larger version.

<a href=”https://keithhennessey.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/obama-long-term-policy.png” target=”_blank” rel=”shadowbox

I am comparing the past 50 years with the next 50 years under President Obama’s proposed policies.

The dotted red line shows us that, over the past 50 years, federal government spending averaged just over one-fifth of the economy (20.2% of GDP). The dotted blue shows us that, over the past 50 years, federal revenues averaged just over 18% of GDP. The small yellow double arrow between the dotted red and blue lines shows the average deficit over the same period: 2.1% of GDP.

The vertical white line at 2011 separates the past from the projected future of the President’s policies.

You can see the assumption of the economy recovering as the blue revenue line recovers from an extraordinary low share of GDP. As more people get jobs, the government will get more income and wage revenues. You can also see spending declining from the 2009-2011 phase which spiked principally because of TARP and stimulus.

Three things should jump out at you from the future portion of this graph:

- The red and blue lines diverge enormously, and the gap grows over time.

- The blue line is flat while the red line slopes upward.

- Both the red and blue lines shift upward significantly.

Let’s take each in turn.

The red and blue lines diverge enormously, and the gap grows over time.

The gap between the red and blue lines is the budget deficit. A deficit of 3% of GDP will hold debt constant relative to the economy. Under the President’s policies the deficit would dip in 2018 to 2.9%, and would otherwise forever be at or above 3%. Our government debt burden will increase forever.

In a crisis our economy can handle an enormous temporary budget deficit. Our deficit problem is that future deficits are large, sustained, and projected to grow forever. Our little yellow double-headed deficit arrow will grow into a monster and keep growing.

The blue line is flat while the red line slopes upward.

Taxes grow as a share of the economy very slowly. The blue line is basically flat for two decades.

I’d like the solid blue line to be below the dotted blue line. Most Congressional Republicans argue to match the historic average of about 18%. The President proposes just below 20%. Reverting the tax code to pre-Bush policies (“repealing all the Bush-Obama tax cuts”) would bring us to the high 20s. In each case the line is basically flat.

The red spending line grows steadily as a share of GDP. That’s because three enormous spending programs are growing at unsustainable rates: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. A better way to think about it is that there are three underlying forces driving spending growth: demographics, unsustainable benefit promises by elected officials, and per capita health spending growth.

At any point in time, the gap between the red and blue lines can be narrowed by lowering the red line, raising the blue line, or both. Over time, however, the red line must be flattened, no matter what level you pick for the blue line. If it’s not, any downward red shift or upward blue shift only temporarily narrows the gap. If you don’t flatten the red line, your solution is only temporary. It’s the slope of the red line that’s killing us.

Both the red and blue lines shift upward significantly.

We care not just about the gap between the red and blue lines, but also about their absolute levels. A higher red line means we are devoting more of society’s resources to federal government control. That leaves less for the private sector (and for state & local governments).

I’m a small government guy, so I want the red line to be as low as possible. Whatever your policy preference about the size of government relative to the private sector, two things are undisputable: bigger government comes at the expense of a smaller private sector, and at some point that growth in government has to stop. This second point is just another way of saying that eventually we have to flatten that red line.

This size-of-government metric is often ignored. Washington fights about whether a policy (like the new health care laws) widens or narrows the gap (the deficit) without asking whether the policy shifts the lines up or down. Both things matter.

You can see that President Obama proposes long-term revenues of about 20% of GDP over the next decade. Other than a brief tick above 20% during the tech stock bubble in the late 90s, that would put federal taxes at an all-time high share of GDP. That difference, between 18.1% of GDP and almost 20%, is enormous.

Those higher taxes are an explicit policy proposal from the President. While the new health laws shifted the red spending line up, most of that long-term path long predates him. The path of entitlement spending has changed over the years, but the shape of this graph has not changed in decades. Pre-crisis and pre-Obama, the spending line would have bumped around 20% for another several years and then would have begun its steady upward growth.

What has changed is that we used to say this was a long-term problem. The financial crisis, economic recession, and the President’s policies have eliminated this small amount of breathing room. This graph makes clear that the long-term problem begins now.

I’ll end with a clean version of this same chart which removes all the explanatory chartjunk.

Sources: This graph combines three tables from the President’s budget – historical data are from, surprise, Historical Table 1-2; the next ten years are from the principal short-term table (summary table S-1); the rougher long term numbers are from (table 5-1 on page 51 of Analytical Perspectives), which provides shares of GDP every 10 years. I combined the streams (the data match in 2020) and interpolated the long run data for intervening years.

The President’s budget: whistling past the graveyard

I chewed on the President’s budget for a few hours today. Rather than bore you with a MEGO (“My Eyes Glaze Over”) post filled with numbers and charts, I offer a few overall qualitative and strategic impressions.

- No big surprises here. The budget tracks the State of the Union address as well as press events and leaks over the past month. There are a few gems, including a hidden 25-cent per gallon gas tax, a State bailout and unemployment tax increase on almost all workers, and a $315 B unspecified Medicare savings gimmick, but those are to be expected.

- Spending, taxes, and deficits would reach new plateaus, each well above historic averages. The President proposes sustained bigger government and bigger deficits and debt. Much bigger.

- The numbers are terrifying. That terror comes not from big new proposals, but from whistling past the graveyard of unsustainable current law.

- The President says his new goal is “to pay for what we spend by the middle of the decade.” This clever language suggests he thinks that, since there was existing government debt when he took office, it is not his responsibility to find ways to pay for even the interest payments on that “inherited” debt. As President, his job is not, however, after eight years to momentarily stop making things worse, as his budget proposes. It is instead to address the challenges the Nation faces, including those that have been building over the past 70 years.

- In mid 2009 a smart friend observed that President Obama was pursuing an ordinary liberal domestic policy agenda at an extraordinary time in the economy. It was as if the severe recession had almost no effect on the President’s outlook. Indeed his chief of staff argued that the national economic crisis created an opportunity to enact the President’s campaign proposals.The same appears to be true with this budget. The President is proposing an ordinary liberal spending agenda at an extraordinary time in our fiscal history. His proposals for increased government spending on infrastructure, technology, and education are straightforward expansions of the role and size of government, in line with what I might expect from a Carter or even Clinton in his more expansive years. Times have, however, changed significantly since the 70s and the 90s. What were then long-term fiscal problems are now short-term looming crises.The fiscal problems of current law, which predate but were exacerbated by President Obama’s expansions of government in his first two years, should be driving the policy agenda. In this budget they are an afterthought. The President’s budget ignores the problem of entitlement spending under current law, and proposes Medicare and Medicaid savings only sufficient to offset a portion of his proposed spending increases. Team Obama’s topline message includes dangerous and misleading reassurances that Social Security is not an immediate problem. Demographics, unsustainable benefit promises, and health care cost growth are the problems to be solved. The President instead wants to build more trains and make sure rural areas have 4G smartphone coverage.

- Budgets represent policy priorities expressed as numbers. It’s easy to focus on the numbers and lose sight of the underlying priorities. For two years America has been debating whether restoring short-term economic growth or addressing our government’s fiscal problems is a higher priority. With his State of the Union address and this budget, President Obama is trying to define a new problem to be solved. He thinks Americans are at a long-term competitive disadvantage relative to the Chinese because our government isn’t spending enough on infrastructure, innovation, and education. Suppose you think he’s right (I don’t). Is this problem more urgent than restoring short-term economic growth? Is it more important than addressing unsustainable deficits and a federal government expansion that will leave fewer resources for the private sector? The President apparently thinks it is. I strongly disagree.

- The President is choosing both a policy path and a campaign strategy. He is betting that having no proposal to address the looming fiscal crisis is better for his reelection prospects than having one.

- The President has made his strategic choice: we are headed toward a two year fiscal stalemate in a newly balanced Washington.

(photo credit: Todd Hall)

The President’s hidden trade message

At the U.S. Chamber of Commerce yesterday the President spoke about trade:

<

blockquote>

This sounds like a free trade agenda, or at least a pro-trade agenda, which would be good from a President whose party often leans heavily toward protectionism. The problem is that the U.S. already has trade agreements with Panama and Colombia. The President is in reality saying that he is undoing those deals. He also appears to be saying that “unprecedented support from … labor [and] Democrats …” is a precondition to further progress on free trade.

When President Obama took office, he found three signed Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) on his desk awaiting Congressional approval: the [South] Korea FTA, the Colombia FTA, and the Panama FTA.

Congress must approve any trade agreement negotiated by the President (more accurately, by his U.S. Trade Representative) with another country. Under normal legislative procedures, the implementing legislation for a trade agreement would be subject to amendments in Congress. Since any trade agreement will make compromises that sacrifice certain geographically or economically limited interests for a broader national benefit, it would be vulnerable to being amended in Congress after it has been negotiated. Foreign negotiators know this. They don’t want to negotiate with the USTR and then have their deal reopened by Congress.

The clever solution to this collective action problem is called trade promotion authority (TPA), formerly known as fast track authority. Congress passes and the President signs a law that gives the President and his USTR authority to negotiate and sign trade deals for a certain number of years. In this legislation, the Congress limits itself to a simple yes-or-no vote on the whole treaty. Through this law they surrender their later rights to amend the treaty when it comes before them. In legislative parlance, we say that the treaty gets a straight up-or-down vote in both the House and Senate.

This binary choice strengthens a U.S. President and his trade negotiator. While they still must convince the foreign power that they can get Congress to support the agreement being negotiated, they don’t have to worry that Congress will amend the agreement. This gives U.S. negotiators the ability to get a better deal, because their counterparts have a high degree of confidence that the U.S. team can deliver on its commitments.

The Korea, Colombia, and Panama FTAs were all negotiated under now-expired trade promotion authority that Congress gave to President Bush. President Bush did not send any of these FTAs to Congress because Speaker Pelosi made it clear she would kill all three trade agreements, either through procedural means or by rallying the votes to defeat them.

When President Obama arrived, he said the South Korea FTA negotiated during the Bush Administration was a bad deal for the United States. Rather than submitting it to Congress for approval, he directed his USTR Ron Kirk to renegotiate certain parts of it with the Koreans. Those negotiations resulted in a new Korea FTA which looks a lot like the old one.

The Korea FTA is a big deal for both the U.S. and Korea. South Korea is our seventh-largest trading partner, and this agreement would rank second only to NAFTA in economic impact on the U.S. Almost two-thirds of U.S. agricultural exports would immediately be duty-free, and tariffs and quotas on almost all other U.S. agricultural goods would phase out over the next decade. The treatment of U.S. beef was a hotly contested issue, as the Koreans argued that a 2003 outbreak of mad cow disease in the U.S. justified continued import barriers. The other contentious issue was trade in autos.

The President now must deal with Republican Speaker John Boehner. Republicans are by no means universally in favor of free trade, but the party leans more heavily in that direction than Democrats. Free trade in the U.S. is typically enacted by a center-right coalition. About a third of Democrats ally with >80% of Republicans to deliver the votes needed. It is therefore easier for the President to get an FTA through with Speaker Boehner than it might have been with Speaker Pelosi.

In his State of the Union address, the President said,

This [South Korea free trade] agreement has unprecedented support from business and labor, Democrats and Republicans – and I ask this Congress to pass it as soon as possible.

This sounds great. Other than some complaining by Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus over beef (and he is a critical legislative player on trade), the South Korea FTA looks like it’s in good shape. We finally have a legislative configuration that should allow the implementing legislation to be quickly enacted.

Isn’t it great that this agreement has “unprecedented support from business and labor, Democrats and Republicans?” The problem is that this unprecedented support, and in particular from labor unions and their allies in Congress, was not costless. In this case, it slowed things down by two years.

We see from yesterday’s remarks that the President wants this to be the model for future trade agreements. This gives labor unions and their Congressional allies tremendous leverage to water down or even block FTAs they don’t like.

Some business leaders at the Chamber probably smiled yesterday when they heard the President say “trade agreement … South Korea … Panama and Colombia.” But opponents of free trade listening carefully heard the President’s hidden message: I am reopening the agreements with Panama and Colombia, and giving you the ability to block them and other future FTAs by denying your support. If labor and Democrats oppose a future free trade deal, it won’t be “the kind of deal I’ll be looking for.”

This will certainly slow things down, and could easily result in a halt to expanded trade as labor unions and other interest groups that oppose free trade leverage the President’s reluctance to go with a center-right strategy.

The President knows that all the economic juice for the U.S. is in the Korea FTA. FTAs with Colombia and Panama would be a big deal for those economies, but not for the U.S. They’re just too small for it to have a measurable economic effect outside of Florida and a few other states.

Congressional Republican leaders fear that they will enact the South Korea FTA and then the President will never get around to finalizing the other two. The President will repeatedly tout the economic benefits of the Korea FTA. At the same time he will say he is hard at work on the other two, but never quite able to bring them to conclusion, because they lack “unprecedented support … from labor and Democrats.” U.S. labor unions that oppose the Colombia FTA argue that the Colombian government has not done enough to crack down on violence against union activists. Their opposition to the Panama FTA hinges on Panama’s rules for allowing unions to be formed.

If the direct economic benefits to the U.S. of the Colombia and Panama FTAs are small, why should we worry about them?

- Colombia and Panama are free and democratic allies in Central America. We want to promote freedom, democracy, and friendship with the U.S. throughout Central America, especially relative to that thug Chavez in Venezuela. We do that by helping their economies grow; by promoting capitalism, free trade, freedom, and democracy; and by further strengthening our ties with them.

- Other small countries outside of Central America will learn about the U.S. from how we interact with these two. We should show the world that we treat all our friends well, not just the ones who can help us economically.

- Every Free Trade Agreement is a small movement in a positive economic direction. Economists (and I) generally prefer a few good multilateral FTAs to many smaller bilateral agreements, but I’ll take forward movement wherever we can get it, especially when protectionism is slowly growing around the world.

- It weakens U.S. trade negotiators in future negotiations when the President (or Congress) reopens past agreements. It should always be the case when you’re negotiating with the U.S. that a deal is a deal.

If you want to put the President’s strategy in a positive light, you would say that he has found a strategy on Korea that seems to be working. He renegotiated that FTA and in doing so mitigated significant opposition from the left, making it highly likely that implementing legislation will be quickly enacted. You would argue that he is now trying to replicate that model with Colombia and Panama, and will submit those for approval when they are good and ready. His strategy is slow, you would argue, but effective. You would admit that this strategy damages negotiations with other countries by reopening previously signed deals, but would argue that this is a small price to pay for broader Congressional support for the final deals.

If you’re a skeptic, you are nervous that the President intends to let Colombia and Panama languish after enacting Korea. This would damage two allies in Central America. It would undermine our ability to strengthen our ties through free trade with other countries, and it would weaken our trade negotiators who would be less able to convince their counterparts that a signed deal would be final. It would give opponents of free trade and open investment further opportunities to slow things down and erect other protectionist barriers.

You are further worried that the President is signaling to domestic interest groups that oppose free trade that he will not move forward without them. This will at best slow progress, and at worst it will kill the Colombia and Panama FTAs, as well as any other free trade opportunities while President Obama is in office.

Senate Minority Leader McConnell and new Senate Finance Committee Ranking Republican Orrin Hatch expressed these concerns in a letter to the President:

We appreciate your support for prompt implementation of the U.S. – South Korea Free Trade Agreement. … We are disappointed, however, not to see the same level of commitment from your administration for trade agreements with Colombia and Panama. … We urge your support in passing these through Congress without delay.

… Colombia and Panama are key allies of the United States in Latin America, a region of particular strategic importance to our country. Further delay in implementing these agreements risks sending the signal to other countries in Latin America that the United States is not interested in closer economic engagement in the region and is unable to follow through on our commitments to our allies.

Finally, given what we believe is broad, bipartisan support in Congress for these agreements, we would like to make clear that we see no need for further negotiations with Colombia and Panama. As currently written, they are solid agreements which benefit our nation and our workers. We are confident that they would receive strong support in the Senate and the House of Representatives. We urge you to immediately engage with Congress to achieve Congressional approval to get these agreements signed into law as soon as possible.

This letter reinforces the same message from Speaker Boehner, “Now more than ever, America needs strong leadership to complete and implement the three pending trade deals in tandem with one another.”

We should neither abandon our friends in Central America nor risk leaving them behind. The President should submit and Congress should quickly pass Free Trade Agreements with South Korea and Colombia and Panama. He should not give labor unions or anyone else the ability to block progress on free trade. This is an area where Congressional Republicans will happily work with the President, if only he will do the same.

(photo credit: Wikipedia)