Why the Clinton ‘95 strategy might not work this time

In 1995 a new Republican House and Senate majority passed two bills. The first slowed the growth of government spending and balanced the budget. The second cut taxes. Because Medicare and Medicaid spending accounted for much of projected future spending growth, most of the savings in the Balanced Budget Act of 1995 came from Medicare and Medicaid.

President Clinton vetoed both bills. In 1995 and 1996 he had two fiscal messages:

- 1995: “Republicans are cutting Medicare and Medicaid to pay for tax cuts for the rich.”

- 1996: “Medicare, Medicaid, Education, and the Environment.”

The second was colloquially known as “M2E2.” Both strategies were effective.

It is not yet clear that there is a revival of or a successor to M2E2, in part because the President has been emphasizing so many different government spending priorities. He may, however, be preparing to return to the 1995 Clinton message.

On Fox News Sunday today, Presidential senior advisor David Plouffe said the President would offer a new budget proposal this week. He said the President would propose additional savings from Medicare and Medicaid. He signaled that the President was open to changes in Social Security, but said nothing about a new Presidential proposal in that area.

The President is obviously moving right (his team would probably say “to the center”) in reaction to last year’s election, recent Republican success in the appropriations negotiations, and the new Ryan budget. The President is setting himself up for the possibility of a negotiated fiscal deal with Congressional Republicans, and is also trying to position himself rhetorically for the 2012 election if there is no deal.

Mr. Plouffe also floated a reprise of the 1995 Clinton strategy:

<

blockquote>… the congressional Republican plan for people over $250,000 in this country, their plan is

This argument was effective for President Clinton in 1995-6, but at least seven things are different today.

- The numbers are worse now. The budget deficit and government spending are both much larger today than in 1995. Medicare and Medicaid are a larger share of the budget now. And unless the President proposes huge new tax increases like a VAT (unlikely) or Medicare and Medicaid savings that match or exceed Chairman Ryan’s (no way), the President’s resultant deficit path will still look worse than Ryan’s. As I showed last week, the difference between the two on taxes is small relative to the difference on spending. If the President’s new proposal results in more deficit reduction than the Ryan budget, he might have a leg up, but I can’t see how he’ll make those numbers work.

- Today there is greater public and Congressional awareness that entitlement spending is driving our fiscal problems.

- Substantively, the 1995 tax proposal would have reduced income tax rates. The Ryan proposal is not to increase income tax rates. The President can argue that’s a tax cut relative to current law, but it’s an important difference. It will be harder (and, I think, misleading) to portray the Ryan budget as “cutting taxes,” especially since the Ryan budget has long-term revenues at 19% of GDP, higher than the historic average of the low 18s.

- Politically, the 1995 Republicans message trumpeted both deficit reduction and tax cuts. The Republican 2011 message pushes spending cuts and deficit reduction, but not tax cuts. Yes, there’s an important pro-growth tax reform component to the Ryan plan, but he says it should be revenue neutral. So while those on the left will argue that Republicans are cutting taxes, this time the Republicans won’t be agreeing with that presentation.

- If the President insists on calling this policy “cutting taxes,” he will be forced to acknowledge that he, too, proposes tax cuts beyond 2012. Given his framing, he will be arguing, “My deficit-increasing tax cuts are OK, but your additional deficit-increasing tax cuts for the rich threaten these important spending programs.” That’s a tougher argument to win, especially given their relative sizes. Last year, the deficit effects of the Republicans’ so-called “tax cuts for the rich” were less than one-fourth the size of the agreed-upon “tax cuts for the middle class.”

- In 1995, President Clinton proposed no tax cuts and vetoed the 1995 tax cut bill. Last December President Obama signed into law an extension of the same tax policies that he now opposes for beyond 2012. Nothing prevents him from proposing to do something different next time, but it weakens his argument that preventing these tax rates from increasing is horrible policy. We also know that he was willing to swallow those higher rates once as a part of a negotiated compromise.

- In 1995, Republicans were not publicly linking the top income tax rates to those paid by small business owners. While this argument does not convince those on the left, it shifted the balance of power in the tax rate debate beginning in 2003, and is a principal reason why the 2001 Bush tax rates will be in place for at least 12 years.

The old Clinton strategies might still work, but a lot has changed since the mid-90s.

(photo credit: Roger H. Goun)

Serious policy differences are not petty politics

Here’s the President, speaking yesterday at a town hall meeting in Fairless Hills, PA. See if you can spot his new theme, as pointed out by POLITICO. It’s not too difficult.

THE PRESIDENT: It’s a plan that says we’re not going to play the usual Washington politics that have prevented progress on energy for decades. Instead, what we’re going to do is we’re going to take every good idea out there.

Again:

THE PRESIDENT: Reducing our dependence on oil, doubling the clean energy we use, helping to grow our economy by securing our energy future — that’s going to be a big challenge. … It’s going to require us getting past some of the petty politics that we play sometimes.

And again:

THE PRESIDENT: So we’ve agreed to a compromise, but somehow we still don’t have a deal, because some folks are trying to inject politics in what should be a simple debate about how to pay our bills. They’re stuffing all kinds of issues in there — abortion and the environment and health care.

And again:

THE PRESIDENT: Companies don’t like uncertainty and if they start seeing that suddenly we may have a shutdown of our government, that could halt momentum right when we need to build it up — all because of politics.

And again:

THE PRESIDENT: I do not want to see Washington politics stand in the way of America’s progress. … You want everybody to act like adults, quit playing games, realize that it’s not just “my way or the highway.”

And again:

THE PRESIDENT: I want to kick-start this industry. I want to make sure we’ve got good customers, and I want to make sure that there’s the financing there so that we can meet that demand. And there’s no reason why we can’t do both, but it does require us getting past some of these political arguments.

When the President says, “I do not want to see Washington politics stand in the way of America’s progress,” he always defines “progress” as his policy goals. If you favor his policies, you are for progress. If not, you are engaged in “petty politics” and “games.”

The President is arguing that those who disagree with his policies are engaged in politics. They are, he argues, motivated not by a well-intentioned difference of opinion about how to improve America, but instead by selfish motives.

This is itself destructive politics, cleverly framed as trying to rise above the fray. It cheapens serious policy debate and makes it harder to reach agreement. It contributes to voters’ cynicism. It means that those responsible elected officials on the other side of the aisle who want to work toward principled compromise must overcome both their anger at being personally attacked, and the heat generated in both parties’ wings by a President who challenges the other side’s good intent. It drives away potential negotiating partners and thereby reduces the likelihood of bipartisan compromise.

President Obama changed the direction of American politics in 2008 and again in 2010. The partisan balance of our government reflects both changes. By attacking the motives of elected officials who ran against and now oppose his policy agenda, the President in effect attacks those voters who disagreed with his policies, started a new political movement, and changed the makeup of Congress.

Of course partisan politics and individual agendas interact with and influence policy debates.

Of course there are individuals, both inside and outside government, who at times provoke conflict for their own narrow self-interest.

Yes, the American partisan political structure and the short attention span of the average voter favor political battle over serious policy debate.

Yes, many in the press and commentariat are attracted by and contribute to ongoing conflict rather than cover the lengthy and complex debate needed to understand serious policy disagreements.

Yes, cable TV, talk radio, the internet, and now social media accelerate the news cycle, shorten our attention spans, and allow Americans to self-select into ideological camps.

Yes, there are plenty of people in both parties who spend most of their time in destructive partisan warfare.

Yes, there are plenty of irresponsible and selfish people in Washington, whose behavior and childishness repulses most everyone else.

Yet except for social media, these are not new forces. There are plenty of serious policymakers on both sides of the aisle who want to make America a better place, but just have different visions of how to do that. And all these negative factors are far less important to what happens in Washington than the serious, well-considered, deep policy disagreements among elected officials and other policy makers.

Paul Ryan has just proposed a plan to change our Nation’s fiscal path to one very different from that proposed by the President. Chris Christie, Mitch Daniels, and Scott Walker are engaged in partisan battles as they try to fix New Jersey, Indiana and Wisconsin state finances. Dave Camp and Orrin Hatch are battling organized labor by working to ensure we enact free trade agreements with Korea and Colombia and Panama. They (and Democrat Max Baucus) are initiating a discussion of fundamental tax reform. Fred Upton and Lisa Murkowski are trying to stop the President’s EPA from raising costs on American farms and businesses. Countless Republicans are trying to stop the implementation of new health insurance mandates and entitlements that they believe hurt America. In each case, these are serious Republican officials engaged in policy battle because they think it’s necessary to improve policy. Their views, electoral success, and actions deserve respect from those who disagree.

If the President wants to reduce the impact of the usual petty Washington politics, the recipe is quite simple. Treat with respect those who disagree with you. Vigorously debate their ideas rather than impugning their motives. Ignore the screamers and rabble-rousers. Stick to your guns while seeking opportunities for principled compromise. And acknowledge that those who disagree with your policy agenda may not all be evil.

(photo credit: White House photo by Samantha Appleton)

Comparing the Ryan and Obama budgets

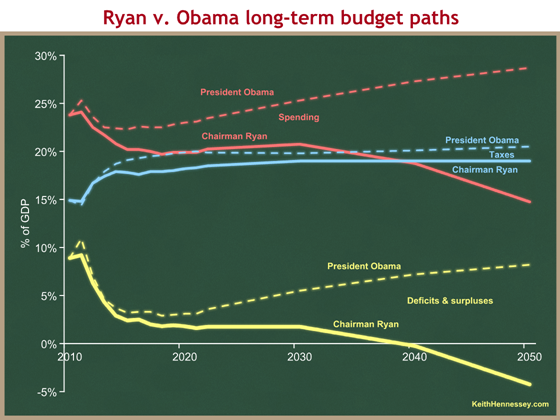

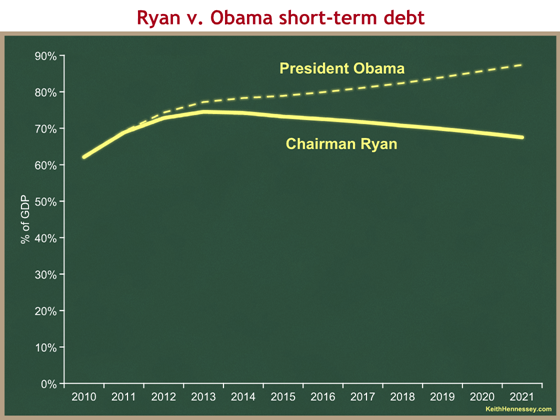

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan released his proposed budget plan yesterday. This will be the focal point of America’s fiscal policy debate for at least the next two years, so I’m going to write about it quite a bit. Today I’ll start by showing you the macro fiscal picture, and by comparing Chairman Ryan’s budget to President Obama’s. Since most people don’t enjoy a good table of numbers as much as I do, we’ll compare them visually.

We’ll look at the short-term first, then the long-term.

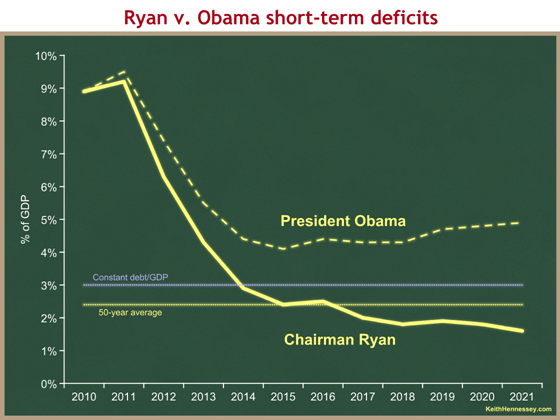

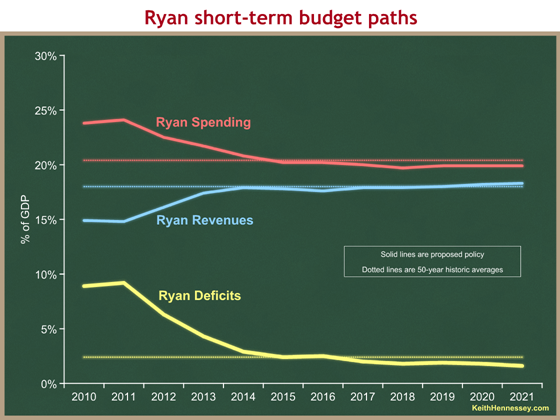

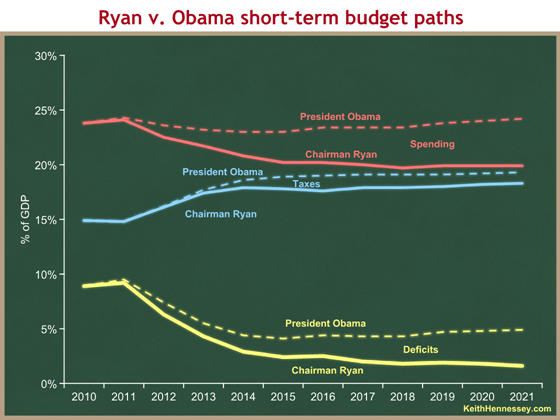

Let’s begin by comparing the short-term deficit effects of the two proposals. On each of the following graphs, solid lines represents Chairman Ryan’s budget and dashed lines represents President Obama’s budget. Spending will always be in red, taxes in blue, and deficits and debt in yellow. Everything is measured as share of the economy. As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

Conclusions:

<

ul>

Now let’s compare the two proposals’ short-term effects on debt held by the public.

Conclusions:

- Chairman Ryan’s budget would result in debt increasing as a share of the economy this coming year and the next one. Debt/GDP would then gradually decline after that, and would be declining at the end of the next decade.

- President Obama’s budget would result in debt increasing as a share of the economy for every year of the next decade, and would end the decade on an increasing trend line.

Deficits and debt are critically important metrics of any budget proposal, but by themselves they provide an incomplete and therefore inadequate picture. We can learn a lot by disaggregating the net deficit numbers into their gross spending and tax components. Let’s set aside the President’s proposal for a moment, and compare Chairman Ryan’s short-term spending and revenues to historic averages.

Conclusions:

- Chairman Ryan’s budget would, within four years, bring spending in line (below, actually) the 50-year historic average share of the economy (20.4%).

- As the economy recovers, revenues would climb to meet the 50-year historic average share of the economy (18.0%) and basically hover around that line over the next decade.

Now let’s compare Chairman Ryan’s and President Obama’s proposed short-term spending and revenues.

Conclusions:

- Over the next decade Chairman Ryan proposes lower spending, lower taxes, and smaller deficits than President Obama proposes.

- The difference in their proposed revenue paths is much smaller than the difference in their proposed spending paths.

- By the end of the decade, Chairman Ryan proposes that taxes be 1% of GDP lower than President Obama proposes. In comparison, Chairman Ryan proposes that spending be 4.3% of GDP lower than President Obama proposes.

- For the last half of the next decade, the Ryan budget would result in stable spending and revenues as a share of the economy. Neither would grow as a share of GDP. In contrast, President Obama’s budget would result in government steadily growing over the next ten years, as government spending consumes an increasing share of society’s economic resources.

- While it’s not shown on this graph, we saw from an earlier graph that the Ryan budget would bring government spending and taxes in line with their 50-year historic averages. Under the President’s budget, government would continue to consume a historically unprecedented large share of the economy, and taxes would rise to high levels relative to the past 50-years.

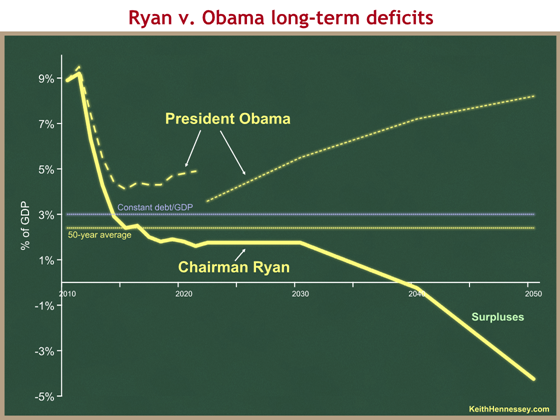

OK, now let’s look at the long run. We’ll start with deficits.

I have two different dotted lines for the President’s deficit path. The short-term path comes from CBO. But since CBO didn’t do a long-term analysis of the President’s budget, I’m forced to rely on OMB’s projections for the President’s long-term deficit. You can see the big gap in 2021, representing the different scoring from two different agencies. This suggests that a CBO projection of the President’s long-term deficit would be higher than what you see here. Thus, this graph probably understates the President’s long-term deficit. It is therefore unfairly generous to the President’s proposal.

Conclusions:

- Chairman Ryan’s budget would result in smaller deficits than President Obama’s budget forever.

- Chairman Ryan’s budget would eventually reach balance and then surplus. The President’s budget would not.

- After bringing the deficit down to the high 1’s by the end of the next decade, the Ryan budget would hold it there for another ten years. The deficits would then decline, resulting in a balanced budget a little before 2040 and ever-increasing surpluses beyond that.

- The President’s budget would result in deficits that never drop below 3% of GDP, and after 2018 increase forever. That deficit path is unsustainable – at some point something in the economy would break.

We’ll end with a comparison of the two proposals on spending and taxes. I have the same data problem as on the last graph. Mixing OMB and CBO numbers for the President’s budget would be way too messy here, so I’m forced to rely on OMB numbers since it’s the only set I have for the full timeframe. This means that the spending and deficit lines for the President’s budget are lower than if I had an apples-to-apples comparison. In other words, this graph is unfairly generous to the President’s budget. Even so, we can still learn a lot.

The key to this graph is to compare the long-term slopes of the red lines, then the blue lines, then the yellow lines.

Conclusions:

- The two proposals have radically different long-term spending lines because the President’s spending slopes up and Chairman Ryan’s slopes down. They are also at different levels, but the difference in slopes is even more important.

- The two proposals have different tax levels, but they are both basically flattish in the long run.

- The ever-increasing gap between the red spending lines dominates the basically stable gap between the blue tax lines.

- The huge and ever-increasing gap between the deficit proposals is therefore a result of fundamentally different approaches on spending. The tax differences between the two proposals are a relatively small component of their different deficit paths.

In these graphs I have shown you only the results of the Ryan budget. I have said nothing about what specific policy changes he proposes to achieve these results. I will write about these soon. In the meantime you can learn more about his proposal at the House Budget Committee website.

Is the goal to fight or to cut spending?

In today’s Wall Street Journal, Janet Hook and Damien Paletta report that FY11 appropriations broke down last week and a “showdown looms.”

While some conservatives demand a high-profile government shutdown, almost two weeks ago I suggested a different strategy:

Instead of threatening to oppose the next CR no matter what, impatient fiscal conservatives should demand that their party leaders ratchet up the the spending cuts in the next CR. Spending cutters, pull the Republican team in your direction. Demand $3B of spending cuts per week rather than $2B. If policy-specific funding limitations are a priority, choose one funding limitation and insist that it be included in the next CR. (I’d choose the EPA regs, which tend to unify Republicans and split Democrats.) Use House Republican control of the legislative text to put the President and Leader Reid in the position where they have to choose between a little more savings and shutting down the government. It’s hard for them to explain why $2B of savings per week is OK, but $3B per week is the end of the world. Use that to your advantage.

I chose that $3B per week figure so that the full-year savings would exceed the $61B of cuts in H.R. 1. In this strategy, if the House passed repeated three-week CRs, with each one cutting $1B more per week than the previous one, they would in effect be ratcheting up the spending cuts by $333M per week for each of the 25 weeks left in this fiscal year.

Let’s examine a slight variant that is even more gradual than what I previously proposed. While negotiating with the President’s team and Senate Democrats, in this variant House Republicans continue to pass short-term Continuing Resolutions as long as there is not an acceptable full-year deal. In these repeated future CRs, they ratchet up the spending cuts by the paltry figure of only $100 million each week. (I previously recommended a bigger ratchet, which would turn once per CR. This is even more incremental, with smaller weekly ratchets.)

Under this new variant, as April 8th approaches House Republicans would pass another three week CR, one which cuts $2.1 B in its first week, $2.2 B in its second week, and $2.3 B in its third week. If another CR was needed after that, it would begin with $2.4 B of savings, and so on until the end of the fiscal year.

Such a tiny weekly increment would be nearly impossible for Democrats to reject. And yet if continued through the end of this fiscal year, $4.5 B of discretionary spending would be cut in the final week, that of September 23rd.

This strategy would result in an additional $82.5 B of spending cuts between April 8th and September 30th, and it poses zero additional risk for Congressional Republicans. They would maintain the high ground on spending cuts and remain on the offensive for the next six months.

Compare that to the $61 B of savings in H.R. 1, which appears to be the upper bound for savings that might be negotiated in a full-year bill. Indeed, even $61 B is too high of an estimate, since a full-year bill would cover at least a month less than when H.R. 1 was originally passed. The President’s negotiators and Senate Democrats have so far offered far less than $61 B in cuts.

I picked the +$100M/week figure to be absurdly small, so that there would be no question Republicans could continue to win the communications battle. For comparison, here is what you’d get with incremental ratchets of +$150M and +$200M per week, rather than +$100M.

| Weekly incremental spending cuts | Cumulative cuts between 8 April and 30 September |

Savings in the last week, of September 23 |

| +$100 M | $82.5 B | $4.5 B |

| +$150 M | $98.75 B | $5.75 B |

| +$200 M | $115 B | $7 B |

In this version of the ratchet strategy I have left out the policy-related funding limitations: precluding funding for ObamaCare, for new EPA greenhouse gas rules, for National Public Radio or for Planned Parenthood. Those are also unlikely accomplishments in a shutdown strategy. Nevertheless, as the spending cuts ratchet up over time, there would be ever-increasing pressure on Democrats to agree to a full-year bill. The price of that agreement could include a funding limitation.

On today’s Wall Street Journal editorial page, Fred Barnes writes that “Republicans are Winning the Budget Fight”:

Would a shutdown give Republicans more muscle in negotiating for cuts? Some Republicans speculate it would “clarify” the sharp differences between what Republicans are seeking and what Democrats want, prompting most Americans to side with Republicans. Maybe it would. But it might not.

If Congressional Republicans’ goal is a spending showdown with the Democrats at the O.K. Corral, then by all means push for the clarity of a shutdown.

The arithmetic shows that such public messaging clarity would cost taxpayers between $21 B and $54 B, compared to a near-zero risk, gradual ratchet of +$100 M to +$200 M per week.

For some conservatives it’s about having a public fight.

For me it’s about the money.

(photo credit: RileyOne)

Deficits are an important but incomplete metric

The budget debate will soon expand beyond the current short-term fight. Negotiations on appropriations funding for the remainder of FY11 continue, and a government shutdown on April 9th is quite possible. I will write about that battle as events dictate, but hope to focus most of my attention on the more important big fiscal picture.

The following discussion may seem a bit theoretical. I think it’s an important starting point.

Washington traditionally focuses its attention on the federal budget deficit, the difference between government spending and revenues. We need to expand our scope and think about two allocation decisions made in each year’s budget debate.

The first decision is how much of society’s resources we want to allocate to the federal government. For sixty years from 1950-2009 this number was surprisingly stable. Total federal government spending averaged about 20% of GDP. The other four-fifths was private sector spending by individuals, families, and private businesses, plus spending by State & local governments.

A better and more difficult analysis would compare the allocation of resources between the public and private sectors. Since Washington directly decides only how much the federal government will spend, we end up with federal government vs. everything else.

The second decision is the timing of how we want to allocate the financing of that government spending over time. How much of this year’s federal government spending should be financed through current taxes, and how much through future taxes? Over that same 60-year period, that 20% of federal spending was allocated 18-2. Federal taxes averaged about 18% of GDP, and budget deficits averaged about 2% of GDP.

(Data is from OMB’s historical tables, and these numbers don’t move by more than a couple tenths of a percentage point if you shift the historic windows by several years. It’s always 20-18-2.)

I therefore hope you will remember the following numbers, which pretty much define the big picture of federal budget policy for a 60-year period:

- Washington policymakers allocated 20% of our economy to Federal government spending, leaving the other 80% for private spending by individuals, families, and businesses, along with State & local government spending.

- That government spending of 20% of GDP was allocated 18-2: Elected officials taxed their citizens by 18% of GDP, and they borrowed the other 2%. That borrowing, plus the interest that accumulates on it, represents a burden on future taxpayers.

I write it this way: (80/20, 18/2).

At a macro level, those four numbers tell you a ton about federal budget policy, and they provide much more information than if you look only at the average budget deficit over that timeframe (2).

Most of Washington focuses only on the 2. The budget deficit is an incredibly important number in fiscal policy. It represents the tax burden this generation of policymakers is placing on future citizens. That’s a huge deal. These officials are making decisions to allocate the earnings of future taxpayers before those taxpayers earn it, before they can vote, and in some cases before they even exist.

At the same time, if we look only at the budget deficit, we miss the other macro decision. The budget deficit is a critical but incomplete measure of macro fiscal policy. At this level we need to consider two dimensions of each decision, not just one.

Let’s look at two examples.

Example 1: Two very different balanced budgets

- Case A: The federal government spends 25% of GDP each year and collects the same in tax revenues. 75% of GDP is available for the private sector plus State & local government.

- Case B: The federal government spends 20% of GDP each year and collects the same in tax revenues. 80% of GDP is available for the private sector plus State & local government.

In my notation, Case A is (75/25, 25/0), and Case B is (80/20, 20/0).

Both A and B are balanced budgets. In both cases current taxpayers are financing all of today’s government spending. No financing burden is being imposed on future taxpayers.

The traditional Washington deficit-only debate would treat A and B as if they were the same policy, because both have zero deficits. That is a critical and dangerous oversimplification.

These are clearly quite different policies. B is a much bigger private sector and a much smaller federal government than A.

Depending on what the additional government resources are used for in A, and from whom in the private sector they are taken, different people will come to different conclusions about which policy they prefer. For now my point is simply that they are different, yet Washington treats them as if they’re not.

Example 2: A big balanced budget vs. a smaller government financed in part by deficits

- Case C: The federal government spends 25% of GDP each year, financed entirely by 25% of GDP in current taxes and with no budget deficit.

- Case D: The federal government spends 20% of GDP each year, financed by 18% of GDP in current taxes and 2% budget deficits (= future taxes, with interest).

Note that I equate budget deficits and futures taxes, with interest. A dollar borrowed by the government today represents a claim on future taxpayers. Since the government has to pay to use this money now, future taxpayers also have to pay the interest costs on those deficits, so they will have to pay more than a dollar in future taxes to finance a dollar of today’s government spending.

In my notation, C is (75/25, 25/0) and D is (80/20, 18/2). When comparing C and D, we need to compare not just the zero and the 2, but also the 25 and the 20, or the flip side of this, the 75 and the 80. And to decide which policy we prefer, both allocations matter.

In a traditional deficit-only Washington policy debate, C looks better than D. C is a balanced budget and D has a 2% deficit, therefore imposing costs on future taxpayers. This is a flawed analysis because it is incomplete.

I don’t want to shift costs into the future, so I like the balanced budget of C better than the budget deficits of D. I like the zero better than the two. I also want a bigger private sector and a smaller government, and in this respect 80 of D is far better than the 75 of C. Whether you prefer C or D therefore depends on your preferences on both questions:

- On the margin, should more of society’s economic resources be controlled by the federal government, or by private individuals, families, firms, and State & local government?

- And how much of our current federal government spending should be financed by current taxpayers, and how much should be shifted to future taxpayers?

Your answer will also probably depend on the uses of the additional government spending, and how and from whom those additional taxes are collected. It should also depend in part on the numbers involved. The relative importance between the size-of-government question and the timing-of-financing question changes a lot when you’re looking at 7 and 10% budget deficits, compared to 2% deficits.

Almost all elected officials of both parties will tell you (and believe) that deficits are bad, that they don’t want to shift financing costs to future taxpayers. Yet they have a political incentive to do so, since they gain the political benefits of promising all sorts of government stuff today, and they have an incentive to avoid the political costs of imposing higher taxes on today’s voting taxpayers.

And while the public debate centers around budget deficits, the first allocation question is harder to resolve. The deep philosophical and partisan split in the American fiscal policy debate is mostly about the relative sizes of the government and the private sector, not about the allocation of the cost of that government between the present and the future.

I draw three conclusions.

- Budget deficits are very important. They represent a critical policy choice, the allocation of government financing costs between the present and the future.

- A fiscal analysis that focuses only on the deficit is incomplete, because fiscal policy is also about how our elected officials choose to allocate resources between the private and public sectors. There are two value choices, not one, and if we focus on only the budget deficit, we will have incomplete information, get confused, and make bad decisions.

- We think we’re fighting about the deficit, when in reality the deep philosophical and political divide in America is mostly about the relative sizes of government versus the private sector.

(photo credit: Randy Robertson)

What happened to stimulus vs. austerity?

For two years American policymakers battled. Those on the left argued that America’s top economic policy priority was addressing an extremely weak short-term economic picture, and that fiscal stimulus was the solution.

Those on the right argued that fiscal stimulus wouldn’t work or wasn’t worth it. They argued that addressing America’s long-term fiscal problem was at least as important as our weak short-term economy. Government fiscal austerity, they argued, was the best way to increase expectations of future economic growth, which would drive a faster short-term recovery. In addition, that fiscal austerity would directly address our Nation’s most important long-term policy problem.

President Obama initiated this debate in early 2009 by proposing almost $800 B of fiscal stimulus.

Two years later, in his 2011 State of the Union address, the President pivoted. America must focus on the long run, he now argued. But rather than joining the growing policy consensus that we must address our government’s fiscal problem, the President tried to define a new problem to solve.

From out of the blue, President Obama argued that America’s principal economic challenge is wage competition from China and India. We are in a race with China and India, he argued, just like we were in a Space Race with the Soviet Union in the late 1950s.

We need to Win the Future, he said, by copying the Chinese:

Meanwhile, nations like China and India realized that with some changes of their own, they could compete in this new world. And so they started educating their children earlier and longer, with greater emphasis on math and science. They’re investing in research and new technologies. Just recently, China became home to the world’s largest private solar research facility, and the world’s fastest computer.

… We know what it takes to compete for the jobs and industries of our time. We need to out-innovate, out-educate, and out-build the rest of the world.

… This is our generation’s Sputnik moment.

The Soviets launched a satellite and so we had to. The Chinese are educating and investing, so we must as well.

It’s hard to think of a less apt comparison. The Soviet Union was our enemy. China is not. India is our friend, the world’s most populous democracy, and has an economy moving in fits and starts toward free market capitalism.

The Space Race was a zero-sum game. Our more complex economic relationships with China and India involve both competition and areas of mutual interest. Their workers compete with ours as part of a global labor supply, but the price competition also makes it less expensive for Americans to buy stuff.

The President’s logic is that we should match the Chinese, policy for policy. The Chinese are building high-speed trains, therefore the U.S. should do the same. The Chinese are spending more on education, therefore the U.S. should spend more on education. The Chinese are subsidizing green tech R&D, therefore the U.S. should offer such subsidies, for fear of otherwise losing the green tech race.

The Chinese and Indian economies are radically different from our own and from each other. There’s no logical reason why our government’s economic policies should mimic either of theirs. And if you’re going to choose one, why should the U.S. emulate the Communist Party of China rather than the developing free market capitalism of democratic India? The President’s wage competition argument applies equally to both nations.

A better path is for the U.S. government to implement policies that make sense for the U.S., no matter what China and India do. American economic policy changes should focus on solving American policy problems and maximizing future productivity growth here at home.

The short-term U.S. economy appears to have stabilized but is still quite weak. The fiscal stimulus advocates have gone quiet, either because they have given up on the argument or because they know they cannot succeed legislatively. With an 8.9% unemployment rate and a future recovery path measured in years, it’s impossible to argue that fiscal stimulus was a success. Only Dr. Krugman is left to wave the stimulus banner, hurl invective, and call everyone stupid.

Far more constructively, yesterday ten former Chairs of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers argued that policymakers should prioritize austerity:

<

blockquote>Repeated battles over the 2011 budget are taking attention from a more dire problem—the long-run budget deficit.

…

… While the actual deficit is likely to shrink over the next few years as the economy continues to recover, the aging of the baby-boom generation and rapidly rising health care costs are likely to create a large and growing gap between spending and revenues. These deficits will take a toll on private investment and economic growth. At some point, bond markets are likely to turn on the United States — leading to a crisis that could dwarf 2008.

So much for Winning the Future. The principal economic policy problem that Washington needs to address is not growing wage competition from China and India. Policymakers should instead solve the long-run fiscal problems of the U.S. federal and State governments.

Stimulus lost the debate. Austerity won. And Winning the Future is a diversion.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Chuck Kennedy)

Gas tax increase or budget gimmick?

On page 188 of the President’s budget, in Table S-8, we see a section titled “Reauthorize Surface Transportation.” That section includes $235 B of spending over the next decade. It also includes a line labeled “Bipartisan financing for Transportation Trust Fund,” and shows a ten-year total deficit effect of –$328 B.

Because of this enormous “Bipartisan financing for Transportation Trust Fund” policy proposal that would reduce the budget deficit, the President’s budget is able to show increased spending for roads, bridges, trains, and airports, yet also reduce the deficit.

What, then, is the President’s proposed “Bipartisan financing for Transportation Trust Fund” proposal?

CBO apparently figured out that the deficit reduction consisted of higher revenues, but the Administration did not provide any more detail. So CBO didn’t give them credit for the –$328 B.

CBO: However, in the case of a proposal to raise new revenues to support the reauthorization of surface transportation programs, the absence of any information about the nature of the taxes or fees that might be used to produce revenues did not allow an assessment of the potential budgetary effects. As a result, CBO did not include any revenues for that proposal, which the Administration projected would raise revenues by $328 billion over the 2012–2021 period. (p. 7)

This language from CBO shows that OMB did not provide any additional back-channel information on this proposal. There’s no there there.

$328 B is a lot of money. You may think you know what this line refers to: a gas tax increase. That’s what I thought. As a rough rule of thumb, the government would raise about $1B per year for each penny per gallon increase in the tax on gasoline and diesel fuel. If we match the numbers in the OMB table, it looks like about +20 +25 cents per gallon in 2012, growing to maybe +35-40 +34 cents by 2021. That’s roughly equivalent to a 25 cent per gallon increase, indexed to inflation. (hat tip: Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Reponsible Federal Budget)

A gas tax fits conceptually with increased transportation infrastructure. There are occasional hints of bipartisan support for higher gas taxes to pay for more infrastructure spending (from Republicans who like to build highways). Higher gas taxes seem consistent with the President’s other policy goals, like reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And the numbers match with commonly discussed proposals for a gas tax increase.

Update: Expert friends have pointed out that other parts of the budget show a $438 B decline in “excise taxes.” A gas tax is an excise tax. There’s a scoring convention that if you cut gross gas tax revenues by $1, demand for gasoline will increase and recoup 25 cents of that lost revenue. Applying a 25% “offset” to this $438 B gross revenue loss produces the $328 B net tax loss shown for the mysterious “financing for Transportation Trust Fund” proposal. This is further evidence that the numbers represent a gas tax increase. It also changes the back-of-the-envelope calculation I did above. Looks like they’re starting out around +25 cents per gallon in 2012.

Yet in both their conversations with CBO (I infer from the text above), and in briefings of Congressional staff (I know from friends), Administration officials were explicit: this line does not represent higher gas taxes.

I can’t come up with any policy other than a gas tax increase that might raise that much money and be described as “Bipartisan financing for Transportation Trust Fund.”

There is only one policy that fits that description. It fits perfectly with the text, the numbers, the political context, and makes policy sense given this President’s policy preferences. And yet the President’s team explicitly reject that policy.

The President’s team is trying to have it both ways: spend money on infrastructure and claim deficit reduction, but don’t take the political hit for proposing a big gas tax increase. CBO has called them on it and is not giving them credit for the $328 B of claimed deficit reduction. That’s a big deal.

Suggested questions for White House Press Secretary Jay Carney:

- Is the President’s “Bipartisan financing for Transportation Trust Fund” proposal a gas tax increase?

- If not, can you describe any other “transportation financing policy,” bipartisan or not, that would raise $328 B over ten years as shown in the President’s budget? If the President wasn’t proposing a gas tax, what else could he have meant?

- If the President did not intend a gas tax increase, how did you come up with those specific year-by-year numbers in the budget? Why $328 B rather than $300 B or $350 B?

- Is this budget proposal a gas tax increase or a budget gimmick?

(photo credit: Charlie Ambler)

The Congressional Budget Office vs. the President

Yesterday the Congressional Budget Office released its preliminary analysis of the President’s budget proposal for FY12. Let’s compare what the President says about his budget with what CBO says. All Presidential quotes are from his February 15th press conference, and all CBO data is from Table 2 of the new analysis and this historical table.

THE PRESIDENT: When I took office, I pledged to cut the deficit in half by the end of my first term.

CBO: The FY09 deficit was $1,413 B, or 10.0 percent of GDP (Tables E-1 & E-2). The President’s budget would result in a FY13 deficit (the end of his first term) of $1,164 B, or 5.5 percent of GDP. (Table 2) By neither measure does the President’s budget meet the test of “cutting the deficit in half by the end of

THE PRESIDENT: Our budget meets that pledge and puts us on a path to pay for what we spend by the middle of the decade. [He later cites 2015.] … On the budget, what my budget does is to put forward some tough choices, some significant spending cuts, so that by the middle of this decade our annual spending will match our annual revenues.

Both “pay for what we spend” and “annual spending will match our annual revenues” refer to the President’s new and easier “primary balance” test, in which he sets a much easier goal for himself – balancing the budge excluding ever-increasing interest payments. I explained earlier why this is an absurd and weak policy goal. Does his budget meet his own weak test?

CBO: In FY2015, the President’s budget would result in a deficit of $748 B, or 4.1 percent of GDP. Net interest payments in that year would be $489 B, or 2.7 percent of GDP. He misses his own goal by $259 B, or 1.4 percent of GDP. CBO’s data shows that the President’s budget does not pay for what we spend by the middle of the decade, nor would “annual spending match our annual revenues.” CBO’s preliminary analysis shows the President’s budget fails his own (weak and insufficient) test of “primary balance.”

THE PRESIDENT: We will not be adding more to the national debt.

CBO: Under the President’s budget, debt held by the public would increase from $13.5 trillion in 2014, to $14.4 trillion in 2015, to $15.3 trillion in 2016, to $16.3 trillion in 2017, and so on. Measured as a share of the economy, it would increase from 78.3% of GDP in 2014, to 78.9% in 2015, to 79.9% in 2016, to 81.1% in 2017, and so on. CBO’s preliminary analysis shows the President’s budget will add more to the national debt, measured either in nominal dollars or as a share of the economy.

CBO and OMB always come up with slightly different estimates for the President’s budget. These differences are not slight. If the President were to use CBO’s numbers, he could not say that his budget “cuts the deficit in half by the end of his first term,” nor that it “pays for what we spend by the middle of the decade” nor that “we will not be adding more to the national debt.”

(photo credit: The White House /Pete Souza)

The Schumer maneuver

Last week Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY) made news by proposing a “reset” of FY11 appropriations negotiations. He suggested substituting savings from Medicare and Medicaid and tax increases for the cuts being negotiated in discretionary spending.

Congress appears to be on track to enact this week another short-term extension to prevent the government from shutting down. This three week continuing resolution (CR) would, according to the House Appropriations Committee, cut another $6 billion in spending.

The Schumer Maneuver

Senator Schumer is focusing on the aggregate amount of budgetary savings proposed by Republicans. He points out that any given amount of deficit reduction is easier to achieve if you start discussions with a larger share of the total budget pie.

Ongoing CR negotiations are about how and how much to cut from the projected $663 B of nondefense discretionary spending this year. This encompasses much of what we think of as the federal government, including everything from the FBI, federal prisons, Homeland Security, health research, most education spending, the FDA, most foreign aid, financial regulators, national parks and the Environmental Protection Agency, the Labor Department, a lot of veterans’ spending, and a lot of our transportation infrastructure spending.

In comparison, Medicare is $492 B this year after netting out premiums paid by beneficiaries. Federal Medicaid spending is $274 B this year. These two programs alone cost federal taxpayers $766 B this year.

Social Security is even bigger than Medicare or Medicaid, and almost as big as the two combined: $727 B of spending this year.

Senator Schumer also included potential tax increases in his proposed reset.

In one respect, Senator Schumer is right: it’s easier to cut any fixed amount of money out of a larger slice than to cut it out of a smaller slice. If you’re willing to add tax increases to the mix (I’m not), then deficit reduction can be spread across an even broader fiscal policy base.

Senator Schumer is also correct that, if Republicans try to cut only the nondefense discretionary wedge, and if they propose to leave entitlement spending untouched, then they are rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. Because the Big 3 entitlements are on autopilot and are projected to grow faster than the economy, unchecked growth in these programs will after a few years overwhelm any enacted savings in the appropriations wedge. And don’t forget defense/security spending, which can also be trimmed.

Senator Schumer also makes a fairness argument: it is unfair, he argues, to concentrate all the pain of deficit reduction in one part of the budget. He argues that the current negotiations should be expanded to include Medicare, Medicaid, farm programs, and tax increases. He (and his allies) also attack Republicans for refusing to accept this expansion now.

Senator Schumer is once again a vanguard for Democratic strategy. With this maneuver he attempts to wrap around to the right of Congressional Republicans on deficit reduction. Since Republicans have not yet proposed any deficit reduction from the biggest parts of the spending problem, and since he says he is willing to negotiate on those areas, he (is trying to) trump the appropriations-cutting Republicans, while at the same time arguing for less pain from a part of the budget that he likes. His goal is to protect appropriations programs from cuts, and so he proposes to expand the discussions to include other policy areas where he is more willing to accept pain.

Had this argument come from the President, Republicans would be in a box. Had the President proposed specific Medicare and Medicaid savings, and argued for enacting them in lieu of Congressional Republicans’ cuts to nondefense discretionary programs, he could have matched their spending cut rhetoric while mounting a stronger defense of programs he favors.

While clever, the Schumer Maneuver is so far failing for four reasons.

- Neither the President nor, it appears, Democratic Congressional leaders are backing him up. The President punted on proposing significant changes to entitlement spending, and is publicly leaning against expanding the scope of the CR negotiations.

- Senator Schumer is trying to change the already difficult short-term appropriations negotiations. Those involved in the negotiations don’t want to make their own job harder by adding more subject matter to the mix.

- Sen. Schumer weakens his own argument by taking Social Security off the table. It’s hard to credibly argue that we should focus on bigger wedges of the pie while simultaneously exempting the biggest wedge from the discussion.

- House Republicans say they intend to propose entitlement savings as well. If they carry through with this, they will one-up Senator Schumer and neutralize his argument. He wants entitlement savings instead of appropriations savings. If they follow through, House Republicans will propose entitlement savings in addition to appropriations savings. This wipes out Schumer’s attempt to be for more deficit reduction than Congressional Republicans.

Then again, Senator Schumer is smart and strategic. It’s possible he offered this proposal knowing it had little chance of success. Doing so would allow him to justify voting against an appropriations compromise, should one occur, without forfeiting a deficit-reduction argument.

Republicans have so far largely ignored the Schumer Maneuver. I suggest they publicly address his suggestion by saying, “Senator Schumer is right – we need to reduce entitlement spending. We should not, however, cut one part of the budget so that we can spend more in another. We need to cut spending throughout the budget. We’re going to continue cutting appropriations now. We’ll get to entitlements next.”

And then they need to follow through.

(photo credit: Center for American Progress Action Fund)

Intro to nuclear power and the Fukushima plant crisis

I’m going to start occasionally recommending other reading. Much of it will focus on the site I run for the Hoover Institution, Advancing a Free Society. Today, however, I want to promote two excellent things I found that help understand the ongoing problems at the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

The first is Maggie Koerth-Baker’s simple and clear post, Nuclear energy 101: Inside the “black box” of power plants. Maggie wrote this respond to a reader who wrote “The extent of my knowledge on nuclear power plants is pretty much limited to what I’ve seen on The Simpsons.”

The second is geologist Evelyn Mervine’s phenomenal set of telephone interviews with her dad, a retired Naval and civilian nuclear engineer. Through this you can hear near real-time expert analysis of ongoing events.

Thanks to Maggie and to Evelyn and Command Mark Mervine (ret.) for their fantastic posts. Their work blows away anything I have so far seen in the MSM.

(photo credit: DigitalGlobe)