Medicare as we know it

The President and his allies ominously warn that the Ryan plan would “end Medicare as we know it.”

But let’s be honest, how much do you really know about Medicare? If you’re under age 65 there’s a good chance that you know very little about the program. You have had no reason to, at least until now.

Five years ago I had to help a Cabinet Secretary and a senior White House staffer get up to speed very quickly on the absolute basics of Medicare, just the broadest brush strokes. They, like you, needed to understand Medicare principally from a top-down budget perspective, rather than as a participant in the system. I created a simple two-page outline for them to study.

I have updated the numbers in that document and offer it here, hoping it can provide some basic facts and context to the Medicare component of the current budget debate. This outline won’t make you an expert, but at least you’ll have a starting point.

All numbers below are from CBO, except enrollment data are from the Medicare trustees.

10 things you should know about Medicare

Who gets it and what they get

1. Medicare is a federal government program that pays for health care for seniors and the disabled.

- About 40 million seniors enter at age 65 get their health care through Medicare.

- You cannot enroll early, as you can with Social Security.

- About 8 million disabled are also enrolled.

- That means 1 in 8 Americans are in Medicare.

2. It was created in 1965 to cover only acute care costs. The cost-sharing structure is “upside down.”

- The benefit was modeled after an early 1960s Blue Cross/Blue Shield benefit.

- It has low deductibles and copayments.

- It does not cover catastrophic costs.

- It generally does not cover long-term care costs (with caveats).

- Part A = Hospital care (+ more)

- Part B = Physician care (+ more)

- Other benefits include home health care, skilled nursing care, hospice, & now drugs (Part D).

- Modern private health insurance instead generally has high deductibles and copayments and often covers catastrophic costs.

3. Most seniors don’t face the costs of the limited deductibles or copayments.

- Many have employer-provided “wraparound” coverage;

- or they purchase supplemental “Medigap” insurance (which is inefficient);

- or the poor have Medicaid cover their cost-sharing.

4. The Bush Administration and Congress added a voluntary drug benefit in 2003.

- Medicare now subsidizes the purchase of privately-offered insurance that covers prescription drug costs, with specific cost-sharing requirements.

How it’s delivered

5. For most it’s a government-financed, government-administered, fee-for-service benefit.

- aka “single payer health care”

- Three-fourths of Medicare beneficiaries are in this “traditional fee-for-service Medicare.”

- Government sets prices in FFS Medicare through laws and administrative mechanisms.

- A senior goes to a doctor or hospital, gets treated. The government reimburses that provider.

- In FFS Medicare, the government therefore directly reimburses and regulates providers of medical goods and services.

- This is slow, bureaucratic, and subject to political influence through the legislative and regulatory processes.

6. One quarter of beneficiaries are in a better “defined contribution” system in which the government finances the purchase of privately-offered health insurance.

- This is “Part C”, aka “Medicare Advantage” or “MA.”

- This looks like employer-provided health insurance, except the government is the premium payer.

- In MA, the government reimburses and regulates private insurers, who in turn reimburse and manage providers of medical goods and services.

- Seniors can choose among competing private health plans. Those plans can more flexibly manage medical providers and costs.

How it’s financed

7. It’s enormous and it’s growing unsustainably fast.

- About $491 billion of net government spending this year. (Compare SS at $727 B.)

- It’s projected to grow ≈ +5.4% per year for the next ten years.

- Medicare spending = 3.8% of GDP today, 4.1% of GDP in 2030.

- Per beneficiary net government spending ≈ $10,200/year

- 70/10 rule: 10% of the seniors account for 70% of the costs. The healthiest 50% of seniors account for only 4% of the costs.

8. It has all the demographic challenges of Social Security, plus unsustainable health care cost growth.

- Medicare is so big that its payment structures are directly responsible for much of the macro- and micro-structure of U.S. health care delivery.

- Politically it’s harder to reform than Social Security because provider groups (doctors, hospitals, etc.) join seniors in lobbying for more funding.

9. There are three main sources of financing the program.

- There are three financing sources: dedicated payroll taxes, beneficiary premiums, & general revenues (income taxes).

- payroll taxes: 2.9% of all wages. ½ paid by employee, ½ by employer.

- premiums: 25% of “part B” costs ≈ $96-115 per month. High income seniors (income > $85K/person) pay higher premiums.

- premiums: a % of “Part D” drug costs. (complex formula). High income seniors pay higher premiums.

- general revenues = total spending – (payroll taxes + premiums)

10. The “Trust Funds” are misleading anachronisms.

- The distinctions between parts A, B, C, and D are historic and irrational.

- Technically, payroll taxes are dedicated to “part A” (hospital) spending, and go into a “Part A trust fund.”

- Technically, part B premiums cover 25% of part B spending, with general revenues covering the other 75%.

- There is some symbolic aspect to the “balance” in the “part A trust fund”, but we think about spending on a cash flow and aggregate basis.

(photo credit: Stanford Medical History Center)

Understanding the S&P report

Yesterday’s report by Standard & Poor’s on the U.S. government’s credit rating is driving headlines. You can learn a lot more from reading the primary source document than from news coverage of it.

Here is what S&P did:

On April 18, 2011, Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services affirmed its ‘AAA’ long-term and ‘A-1+’ short-term sovereign credit ratings on the United States of America and revised its outlook on the long-term rating to negative from stable.

The news is in the latter part: S&P downgraded its “outlook on the long-term

S&P told us why they downgraded their outlook:

We believe there is a material risk that U.S. policymakers might not reach an agreement on how to address medium- and long-term budgetary challenges by 2013; if an agreement is not reached and meaningful implementation does not begin by then, this would in our view render the U.S. fiscal profile meaningfully weaker than that of peer ‘AAA’ sovereigns.

… Despite these exceptional strengths, we note the U.S.’s fiscal profile has deteriorated steadily during the past decade and, in our view, has worsened further as a result of the recent financial crisis and ensuing recession. Moreover, more than two years after the beginning of the recent crisis, U.S. policymakers have still not agreed on a strategy to reverse recent fiscal deterioration or address longer-term fiscal pressures.

In 2003-2008, the U.S.’s general (total) government deficit fluctuated between 2% and 5% of GDP. Already noticeably larger than that of most ‘AAA’ rated sovereigns, it ballooned to more than 11% in 2009 and has yet to recover.

The S&P analysts base their outlook downgrade on a legislative assessment that I think is accurate:

We view President Obama’s and Congressman Ryan’s proposals as the starting point of a process aimed at broader engagement, which could result in substantial and lasting U.S. government fiscal consolidation. That said, we see the path to agreement as challenging because the gap between the parties remains wide. We believe there is a significant risk that Congressional negotiations could result in no agreement on a medium-term fiscal strategy until after the fall 2012 Congressional and Presidential elections. If so, the first budget proposal that could include related measures would be Budget 2014 (for the fiscal year beginning Oct. 1, 2013), and we believe a delay beyond that time is possible.

Standard & Poor’s takes no position on the mix of spending and revenue measures the Congress and the Administration might conclude are appropriate. But for any plan to be credible, we believe that it would need to secure support from a cross-section of leaders in both political parties.

If U.S. policymakers do agree on a fiscal consolidation strategy, we believe the experience of other countries highlights that implementation could take time. It could also generate significant political controversy, not just within Congress or between Congress and the Administration, but throughout the country. We therefore think that, assuming an agreement between Congress and the President, there is a reasonable chance that it would still take a number of years before the government reaches a fiscal position that stabilizes its debt burden. In addition, even if such measures are eventually put in place, the initiating policymakers or subsequently elected ones could decide to at least partially reverse fiscal consolidation.

Let’s tease this apart. S&P describes three distinct but related risks:

- The risk of no agreement on a medium-term fiscal strategy before the 2012 election;

- The risk that, if there is an agreement, it will be phased in too slowly;

- The risk that delay plus a slow phase-in allows enough time for future policymakers to partially undo an agreement.

I think all three are valid concerns, and I share their skepticism.

They describe other short-term fiscal risks that worry them as well:

- the risk of further financial bailouts;

- the potential cost of “relaunching” Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which they estimate at “as much as 3.5% of GDP (!!!);

- the risk of losses on federal loans (they single out student loans).

The first bullet here is scary, and they emphasize it: “Most importantly, we believe the risks from the U.S. financial sector are higher than we considered them to be before 2008.”

S&P comments on three elements of recent deficit reduction proposals: income tax rates, entitlement reform, and the President’s new trigger.

On income tax rates:

Revenue [in the President’s new proposal] would be increased via both tax reform and allowing the 2001 and 2003 income and estate tax cuts to expire in 2012 as currently scheduled—though only for high-income households. We note that the President advocated the latter proposal last year before agreeing with Republicans to extend the cuts beyond their previously scheduled 2011 expiration. The compromise agreed upon in December likely provides short-term support for the economic recovery, but we believe it also weakens the U.S.’s fiscal outlook and, in our view, reduces the likelihood that Congress will allow these tax cuts to expire in the near future.

Note that they are commenting on both the fiscal effects of the deal, and how it affects their assessment of the legislative viability of the President’s recent proposal.

On the President’s new trigger proposal:

We also note that previously enacted legislative mechanisms meant to enforce budgetary discipline on future Congresses have not always succeeded.

This is a poke at the credibility of the President’s trigger mechanism.

On entitlement reform:

Beyond the short-term and medium-term fiscal challenges, we view the U.S.’s unfunded entitlement programs (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) to be the main source of fiscal pressure.

Note that they agree with Chairman Ryan (and me) that entitlement spending is “the main source of fiscal pressure.”

S&P scolds American policymakers by comparing them to their counterparts in other countries. The U.K., France, Germany, and Canada have all begun implementing austerity programs, even while they suffered recessions comparable to or larger than what we had here in the U.S.

S&P concludes with a concrete probability assessment:

The negative outlook on our rating on the U.S. sovereign signals that we believe there is at least a one-in-three likelihood that we could lower our long-term rating on the U.S. within two years. The outlook reflects our view of the increased risk that the political negotiations over when and how to address both the medium- and long-term fiscal challenges will persist until at least after national elections in 2012.

They also tell policymakers the standard against which they will be judged:

Some compromise that achieves agreement on a comprehensive budgetary consolidation program—containing deficit reduction measured in amounts near those recently proposed, and combined with meaningful steps toward implementation by 2013—is our baseline assumption and could lead us to revise the outlook back to stable. Alternatively, the lack of such an agreement or a significant further fiscal deterioration for any reason could lead us to lower the rating.

S&P is telling Washington, that to avoid a possible downgrade, they need to do a deal “in amounts near [$3-4 trillion over the next decade]” and “with meaningful steps toward implementation by 2013.”

In yesterday’s press briefing, White House Press Secretary Jay Carney disagreed with S&P’s skepticism about a deal:

As for its political analysis, we simply believe that the prospects are better. We think the political process will outperform S&P expectations. The President is committed, as he made clear in his speech on Wednesday, to moving forward in a bipartisan way to reach common ground on this important issue of fiscal reform. And he believes that the fact that Republicans — that he and the Republicans agree on a target — $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 to 12 years — is an enormously positive development. They also agree that the problem exists. So the third part is the hard part, which is reaching a bipartisan agreement. But two out of three is important. And it demonstrates progress.

My view

There is a high probability of incremental spending cuts being enacted this year and next as part of debt limit legislative struggles. I’ll make a wild guess of $100B – $300B over 10 year range.

There is a moderate chance (1 in 3) of an incremental, slightly bigger (maybe $300B – $500B over 10 years) deficit reduction deal before the 2012 election. The President would trumpet such a deal as a good first step, but it appears this would fall far short of what S&P says is needed.

Given the President’s apparent budget strategy, there is at the moment a vanishingly small chance of a big medium-term or long-term deal like that described by S&P as necessary to avoid a possible downgrade, ($3-4 trillion over 10 years, with even bigger long-term changes to Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid).

The greatest obstacle to constructive negotiations is the President’s attack rhetoric, in which he today accused Congressional Republicans of “doing away with health insurance for … an autistic child” and potentially causing future bridge collapses like the one in Minnesota that killed 13 people.

Maybe the S&P report will scare the President’s team into treating the long-term problem seriously rather than using it as a campaign weapon. I’m not holding my breath.

(photo credit: Marjie Kennedy)

The President’s “matching deficit reduction” claim is off by a trillion dollars (or more)

In his weekly radio address the President said:

Now, one plan put forward by some Republicans in the House of Representatives aims to reduce our deficit by $4 trillion over the next ten years.

… That’s why I’ve proposed a balanced approach that matches that $4 trillion in deficit reduction.

In the radio address the President did not give a timeframe for his $4 trillion in deficit reduction. He did in his budget speech last Wednesday, however:

So today, I’m proposing a more balanced approach to achieve $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 12 years.

$4 trillion in deficit reduction over 12 years does not “match” $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years. It’s not even close.

The twelve year timeframe is a red flag. Federal budgets are measured over 1, 5, and 10 year timeframes. Any other length “budget window” is nonstandard and suggests someone is playing games.

The President and his team have not yet provided sufficient detail for us to know precisely how his $4 trillion of deficit reduction is distributed over this 12 year window, but we can make some back-of-the-envelope guesses to get a feel for the magnitudes involved.

Based on my experience and until we get more detail from the Administration, I think it’s reasonable to assume the deficit reduction in the President’s plan increases linearly over time. Medicare and Medicaid savings generally fit this pattern, as do gradual plans to slow the growth of defense spending. After a jump in year 2, higher tax revenues should grow roughly with the economy.

If we assume the deficit reduction is a straight line increasing from year 1 to year 12, then $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 12 years would look like this:

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Total |

| Savings $B | 51 | 103 | 154 | 205 | 256 | 308 | 359 | 410 | 462 | 513 | 564 | 615 | 4,000 |

In this scenario, $4 trillion of deficit reduction over 12 years translates into about $2.8 trillion over 10 years. Because this scenario is linear, 29% of the savings would occur in years 11 and 12.

From the White House fact sheet, we know the timing of the President’s proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings:

the framework would save an additional $340 billion by 2021, $480 billion by 2023

This means that $140 B of his $480 B of health care savings would be in years 11 and 12, just over 29%. While this certainly is not conclusive proof that my overall linear assumption is correct, it is a nice positive reinforcement for that guess.

It’s fairly easy to see what’s going on here. The President decided on about $3 trillion of deficit reduction over 10 years, maybe a little less. He wanted to claim that he was “matching” the Ryan plan in deficit reduction, but was just achieving that same goal in a better way. Matching Republican deficit reduction is a lynchpin of the President’s fiscal argument. He was short by a trillion dollars or more, so he and his team decided to measure his proposal over a different timeframe and hope no one would notice. They lengthened the window by which they would measure the President’s deficit reduction until they matched the $4 trillion over 10 years in the Ryan plan and came up with 12 years.

Yes, these conclusions are based on my assumption of the President’s proposed deficit reduction path. We will see if anyone who challenges that assumption wants to provide their own alternate path that leads to a fundamentally different conclusion. We will also see if the Administration provides us with their actual deficit reduction path.

The President’s new budget plan provides insufficient detail to support his claim of $4 trillion of deficit reduction over 12 years. But if we stipulate that amount, it is likely that the President’s new budget proposal would result in $1 trillion more debt over the next ten years compared to the House-passed Ryan plan, and maybe more.

The President was therefore wildly incorrect when he said, referring to the House-passed Ryan budget plan, “I’ve proposed a balanced approach that matches that $4 trillion in deficit reduction.”

(photo credit: John Watson)

What will the 2012 election mean for fiscal policy?

The President is using “the American people have a choice” language to describe the long-term budget debate. This is code for “We’ll leave this issue unresolved for now, fight about it during the campaign, and whoever wins the election gets their way.”

<

blockquote>THE PRESIDENT:

Thursday I argued this was an element of the President’s new budget strategy.

Normally the “American people have a choice” argument is sound logic. Elections have consequences, and it’s not unreasonable for a victorious President to invoke the election as a mandate for his agenda, just as it is reasonable for the new House Republican majority and larger Senate Republican minority to now be claiming that last November’s elections justify their aggressive efforts to cut spending.

What if, however, President Obama and House Republicans both win reelection in 2012? Can’t both then legitimately make that claim? In fact, since [House] Republicans are the ones who have placed their own reelection in jeopardy by taking a big political risk, if they win reelection, isn’t their claim even more valid?

There are so many variables affecting any election that it’s difficult to tease out what an election result actually means for any particular issue. This complexity notwithstanding, if both President Obama and House Republicans win in 2012, they have parallel arguments of comparable validity.

Even if you disagree, I am certain that both a newly-reelected President Obama and a newly-reelected Republican House would claim an electoral mandate for their policy agenda. I would expect both sides of the fiscal policy debate to be just as committed to and insistent upon their respective fiscal policy positions. In other words, we’d be right where we are now.

Today Intrade markets estimate a 60% chance that President Obama will be reelected, and a 57% chance Republicans will maintain control of the House. The election is so far out that these predictions are nearly meaningless, but they are roughly equal.

What happens if, thanks to the President’s “fight about the long run and win the election” strategy, we spend two years in stalemate and end up right back where we started?

Partisan breakdown of FY11 appropriations votes

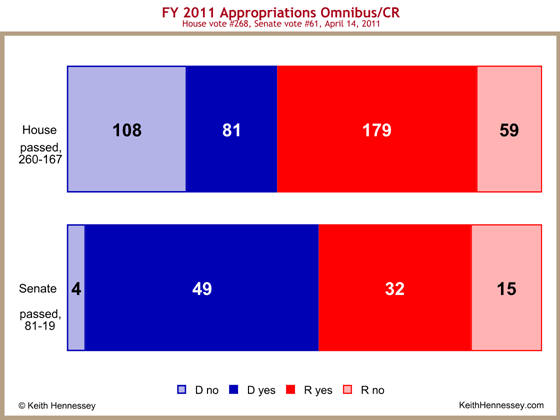

Here is the partisan breakdown for the House and Senate final passage votes on the FY11 appropriations law.

Light shading shows the number of no votes, dark shading the number of aye votes. As always, you can click on the graph to see a larger version.

Note the difference between House and Senate Democrats. I also find it interesting that a greater percentage of Republican Senators (31%) voted no than Republican House members (25%). I would not have guessed that in advance.

Also note that most of the House votes came from Republicans, while most of the Senate votes came from Democrats. This reflects the reality that the majority party in each body almost always provides most of the aye votes for final passage.

President Obama squandered a chance to reach across aisle

I have a new op-ed about the President’s budget speech on CNN’s site. As with most op-eds, I did not choose title. I would have included “President” before “Obama.”

Obama squandered chance to reach across aisle

With his budget speech Wednesday President Obama had an opportunity to reach across the political aisle. He could have proposed a budget plan that focused on the long run, combined needed structural changes to the Big Three entitlement programs — Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid — with the tax increases he wants.

He could have endorsed the proposals of his Fiscal Commission co-chairs, former Clinton Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles and former Republican Sen. Alan Simpson. Their proposal would reform these entitlements, capping government spending and eventually bringing it down to 21% of GDP.

He could have endorsed a bipartisan Medicare reform proposal. He could have proposed a specific Social Security reform proposal to make that program permanently sustainable. He could have taken a political risk for the good of the nation.

The president instead opened his remarks by attacking the only budget plan that would actually solve America’s long-term fiscal problems, that offered by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan.

That budget contains a Medicare reform plan, makes Medicaid spending sustainable, would cause government debt to shrink relative to the economy beginning three years from now, and would put America’s government spending, deficits and taxes on a permanently sustainable path.

The president attacked the Ryan plan and stressed what he will not do: He will not cut spending in medical research, or clean energy technology, or roads or airports or broadband access or education or job training. He will not allow changes to the Affordable Health Care for America Act, which added two huge and unsustainable new entitlements on top of the already unaffordable promises made by past politicians.

If your goal is to foster a bipartisan discussion, you look for something constructive to say about the ideas of your negotiating partners. You disagree with their proposals without attacking their motives. You create a constructive environment that encourages politicians on both sides to take political risks in search of principled bipartisan compromise.

Instead, the president threw down the gauntlet. He made it clear that if you support the Ryan budget, he will attack you. He will accuse you of failing “to keep the promise we’ve made to care for our seniors,” despite the explicit commitment in the Ryan budget that it would only affect future retirees.

The president offered two specific new spending cut proposals. He proposed to cut the amount the government pays for prescription drugs in Medicare and Medicaid. He proposed to crack down on states that gimmick their Medicaid accounting.

Every other spending cut he proposed is a mirage. His Fiscal Commission proposed to “replace the phantom savings from scheduled Medicare reimbursement cuts that will never materialize … with real, common-sense reforms.” The president instead proposed to increase those very same phantom savings and he claims hundreds of billions of dollars of deficit reduction from doing so.

He committed to cut defense spending but gave no specifics. He said he would “conduct a fundamental review of America’s missions, capabilities, and our role in a changing world,” one month after committing American military forces to a third front, in Libya. It is dangerous to simultaneously expand the mission of America’s military and cut their resources.

And he keeps returning to taxing the rich. But while the tax policy differences between the parties are real and significant, they are small compared to the differences on entitlement spending.

The president’s budget speech was an effective way to launch the 2012 campaign. He has set up a debate about the future of fiscal policy and the role of government.

He has positioned himself to attack those who propose an alternative — and, in my view, more responsible — fiscal path for America. He has electrified the third rail and now dares the other party to grab hold.

He has poisoned the well for bipartisan negotiations, killing any chance of a grand budget bargain in the next 18 months. With a single speech he has relegated America to two more years of partisan budgetary stalemate, as we drift closer and closer to fiscal oblivion.

(photo credit: djclear904)

KQED’s Forum

Thanks to Michael Krasny for having me on KQED’s Forum this morning to discuss the President’s budget speech. Clinton CEA Chair and Obama outside advisor Dr. Laura Tyson and I discussed and debated the Obama and Ryan approaches for about half an hour.

This is my second time on Forum, both times with Dr. Tyson. I’m not sure if that’s an R-D thing or a Stanford-Cal thing. Once again Mr. Krasny was an excellent host and interviewer.

You can listen here if you like.

The President’s budget strategy

Yesterday I analyzed the substance of the President’s new budget proposal.

More important than the substance of his proposal, though, was his aggressive attack on the Ryan budget and those proposing it.

Jake Tapper captured it perfectly by comparing two quotes from President Obama.

At the House Republican retreat in January, 2010:

THE PRESIDENT: We’re not going to be able to do anything about any of these entitlements if what we do is characterize whatever proposals are put out there as, “Well, you know, that’s — the other party’s being irresponsible. The other party is trying to hurt our senior citizens. That the other party is doing X, Y, Z.”

THE PRESIDENT: One vision has been championed by Republicans in the House of Representatives and embraced by several of their party’s presidential candidates…This is a vision that says up to 50 million Americans have to lose their health insurance in order for us to reduce the deficit. And who are those 50 million Americans? Many are someone’s grandparents who wouldn’t be able afford nursing home care without Medicaid. Many are poor children. Some are middle-class families who have children with autism or Down’s syndrome. Some are kids with disabilities so severe that they require 24-hour care. These are the Americans we’d be telling to fend for themselves.

The news of yesterday’s speech was the strategic direction the President revealed through these attacks, not the substance (what little there was) of his proposal.

Between now and Election Day I think the President wants:

- a small deficit accomplishment to rebuild credibility with independents;

- a vigorous and political tax fight; and

- the political benefits of scaring senior citizens.

The President made his budget strategy clear.

- Try for a small short-term bipartisan deficit reduction deal this year – tweaks to Medicare, Medicaid, and other entitlements, maybe combined with some defense cuts. Save maybe $100 – $400 B over 10 years, roughly an entitlement parallel to the recent appropriations deal. Use the new VP-led negotiating process to steer those negotiations. See if you can split off a few Senate Republicans from the pack.

- Push for tax increases as part of this short-term deal, but abandon them as needed to get to a deficit reduction signing ceremony.

- Get a signing ceremony for this bill to demonstrate the President can work with “reasonable Republicans.” The photo op of the President signing a bill with Republicans standing next to him is critical for the 2012 campaign. Frame the bill as a demonstration of good faith and a first step toward a long-term solution.

- Use the photo, combined with claimed but unsubstantiated deficit reduction from yesterday’s speech, to build credibility with independents for November 2012.

- Blast away at Republicans on the big spending issues. Take long-term entitlement reform off the table, reassuring his base. Demagogue on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

- Pick a fight over the top tax rates, exciting your political base. Try to restore the Clinton 90s framing of “Medicare and Medicaid vs. tax cuts for the rich.”

The President’s new strategy guarantees two more years of fiscal stalemate and poisons the well on the most important economic policy question facing American policymakers: how to permanently solve the long-term fiscal problem caused by the unsustainable growth of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

(photo credit: Matt Brubeck)

Understanding the President’s new budget proposal

I will describe in some detail the President’s new budget proposal, then provide a few big picture reactions to it.

I have been keeping my recent posts fairly short. This one is instead more of a reference post, and it is not for the faint of heart. I hope it is useful, I know it is long. Consider yourself warned.

Today the President proposed:

- a negotiating process;

- deficit and debt targets;

- a new budget process trigger mechanism;

- and new spending cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, other entitlements, and defense.

Compared to the budget he proposed in February, he offers no new proposals in non-security discretionary spending (I think), taxes, or Social Security.

Process

The President proposes a 16-person bicameral bipartisan Congressional budget negotiation, led by VP Biden, beginning in early May. Each Congressional leader (Boehner, Pelosi, Reid and McConnell) would name four Members. The group’s goal would be “to agree on a legislative framework for comprehensive deficit reduction.”

The President’s timeframe could foul up the normal budget calendar. This is a consequence of him waiting to go second.

Deficit & debt targets

The President proposes a budget deficit “of about 2.5% in 2015” and that is “on a declining path toward close to 2.0% toward the end of the decade.” (That second test is a mess.) Compared to what he argues he proposed in February (using OMB scoring), that’s only 0.7 percentage points lower in 2015 and only 1 percentage point lower in 2021.

He proposes that debt/GDP be “on a declining path … by the second half of the decade.”

Budget credibility: Quite low, for three reasons.

- Several of the largest specific proposals described below have very low credibility (they’re almost gimmicks).

- All proposals of this nature phase in their changes over time, but these proposals push that farther than most. The later the pain begins, the more time there is for Congress to undo it. The President’s proposal backloads the savings so much that they talk about a 12-year window rather than the traditional 10 years. That’s a sign of a weak proposal.

- OMB says the President’s February budget reduces the 2021 deficit to 3.1% of GDP. CBO said the same policies would result in a 4.9% deficit in that year. That’s a big gap, and the same will likely be true here. CBO is likely to say that the President’s specific policies don’t come close to hitting his stated deficit targets. If they’re right, the trigger would not be a failsafe and would kick in with big tax increases.

Taxes

While the President reiterates two big tax proposals from his February budget, he does not propose explicit new tax increases.

Despite having signed a law last December that prevented income, capital gains, or dividend tax increases for all Americans, the President stresses that next time he will insist that tax rates on “the rich” should go up. Next time begins in 2013. Small business owners, this means you.

He also reiterates his proposal to limit itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers. The lion’s share of revenue loss from individual tax expenditures comes from broad-based and wildly popular preferences: the deductibility or exclusion of home mortgage interest, of retirement plan contributions, of charitable contributions, of state and local income and property taxes, of employer-provided health insurance, and of capital gains. The last two times he proposed this he had almost zero Congressional support, including from his own party.

While he is not proposing new explicit tax increases beyond those he proposed in February, his new trigger proposal would likely result in big tax increases.

The Trigger (“Failsafe”)

The President proposes a new debt trigger, similar to policies in place a couple of decades ago. (The most well known is called “Gramm-Rudman-Hollings.”) The trigger is new and important.

The President’s proposal is structured as an if … then … proposition.

If, by 2014, the debt/GDP ratio is not (stabilized and projected to decline by the end of the decade)

… then certain mandatory spending programs are cut across-the-board, and certain taxes are increased, by enough to ensure the debt meets the “if” test.

It’s unprecedented (but not crazy) to structure this as a debt test rather than a deficit test. As a rule of thumb, a deficit of 3% of GDP roughly keeps debt/GDP stable, so the President’s test is roughly equivalent to:

If, by 2014, the deficit/GDP is not 3%, and below 3% by the end of the decade…

The President’s team thinks that his specific policy proposals would reduce the deficit enough that the trigger would never kick in. He therefore calls it a “failsafe.” In past years the term “backstop” has been used for similar triggers. Under this logic the trigger is not used to force cuts, it’s used to ensure them.

If, however, the President’s scoring is wrong and too optimistic, or if the trigger becomes law but the specific policy changes don’t, then this proposal serves a new purpose: it would be a mechanism that automatically changes policy unless Congress acts to stop it. That’s a big distinction. As a general rule, a backstop trigger has a much better chance of being sustainably implemented than an action-forcing trigger.

Trigger proposals like this pop up every few years. Two big questions about any such proposal are:

- What happens if the trigger kicks in?

- How does this affect Congress’ incentive to legislate?

What happens if the trigger kicks in?

The President’s proposal is similar to past triggers in that it exempts all discretionary spending, Social Security, and interest on the debt. While past triggers limited the amounts that Medicare and Medicaid could be cut, the President’s trigger appears to exempt them entirely. The White House fact sheet says the trigger “should not apply to Social Security, low-income programs, or Medicare benefits.” Elsewhere it says the trigger applies only to mandatory spending.

Assuming that “low-income programs” includes Medicaid, this means the trigger appears to apply to at most about $300 B (if triggered this year) in “other mandatory” spending. Half of that would hit federal retiree payments, a quarter would hit veterans’ benefits (if not defined as “low income”), and the rest would hit smaller things like farm subsidies.

It therefore appears that the President’s trigger would exempt more than 90% of government spending from the automatic across-the-board cut.

The trigger would also raise taxes by implementing “across-the-board spending reductions …

The fog lifts. The across-the-board trigger would apply to less than 10% of federal spending and would also raise taxes. And since it would apply only to itemized deductions, it’s only going to hit a portion of those paying income taxes, which is only a portion of all Americans.

The trigger is, in effect, a tax increase trigger on those who itemize deductions, with a little other mandatory spending thrown in for good measure.

The overwhelming impact of the trigger would be to raise taxes on those who itemize. A much smaller portion of triggered deficit reduction would come from automatic spending cuts.

When you combine the automatic nature of this policy with the absence of specific policies needed to sufficiently reduce spending in the long run, the effect of this trigger would be to shift the burden of future entitlement spending increases away from deficits and onto higher income taxpayers. The future default would be that entitlement spending would grow at an unsustainable rate, and taxes on “the rich” would grow to hold deficits below 3% of GDP.

How does this affect Congress’ incentive to legislate?

Since the overwhelming burden of the trigger would be through tax increases, it would significantly advantage the Left in future fiscal policy battles. Big spenders/taxers would know that, if no future legislation were enacted, automatic tax increases would kick in. They would therefore be better able to walk away from what they think is a bad deal. This is incredibly dangerous if your goal, like mine, is to cut government spending.

Spending

The President proposes specific changes (“cuts”) to Medicare and Medicaid, but it’s questionable how real most of them are. He sets numeric goals for additional savings in discretionary spending, both for defense and nondefense, as well as for “other mandatory” programs, but he does not offer specific spending cut proposals in any of these areas. In some cases that’s legit, in others it’s not.

He once again punts on the largest component of federal spending, Social Security ($727 B this year).

Medicare

The President proposes incremental changes to Medicare that would slow its growth in the short run. These changes focus on cuts to provider payment rates. Doctors, hospitals, and other providers of medical goods and services would receive fewer dollars per service.

The easiest way to think about government Medicare spending is that it’s the product of three factors: the number of people eligible for benefits, times the amount of services each person receives, times the government payment per service. The President focuses entirely on the third factor: government dollars per service. The President contrasts his approach to Paul Ryan’s, in that Ryan tries to get at all three factors. More on this in a later post.

The President singles out drug manufacturers as a specific target for budgetary savings, and otherwise relies almost entirely on the so-called IPAB (Independent Payment Advisory Board) that was created by the health care laws last year. The IPAB is a bunch of appointed officials who, under current law, have authority to recommend changes in Medicare provider payment rates. The President would dial up the budget savings target for the IPAB and give them the authority to force those changes if Congress did not act. A Democratic majority Congress last year rejected giving IPAB this forcing authority, and Congressional Republicans hate it even more.

Giving the IPAB forcing authority is a Medicare parallel to the President’s tax trigger. He thus has a trigger backed up by a trigger.

Budget credibility: The drug savings proposals are real. The IPAB savings are at best highly questionable. The President gets the overwhelming majority of his proposed savings from the latter. Since Medicare savings are the largest component of the President’s proposed new spending “cuts,” reliance on the untested IPAB as a backdoor procedural mechanism is a key budgetary weakness in the President’s plan.

Medicaid & Children’s Health Insurance

The President proposes establishing a consistent federal “match rate” across Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Both are shared federal-state programs, in which the Feds pay a portion of each dollar spent and the State pays the rest. Each State has a different federal “match rate,” and these match rates vary within and across programs for different types of services. This is potentially a good reform, but it’s not clear whether the overall effect would be to increase or cut overall federal spending on these programs. That is super important.

He dings Medicaid reimbursement for drugs, but his big Medicaid savings will come from cracking down on States’ attempts to gimmick their accounting to draw down more federal matching dollars for each State dollar spent. While I want to wait for the specifics, as a general matter this is very good policy, especially for federal taxpayers. Governors will hate it and push back hard, because several of them use these gimmicks to solve their State budget problems.

He’s also got some “reforms” to address high-cost beneficiaries and users of prescription drugs.

Budget credibility: The match rate, drug reimbursement provisions, and State gimmick provisions are real and would save money. I am skeptical that the high-cost beneficiary/drug provisions would actually reduce spending by any significant amount.

Other mandatory spending programs

“Other mandatory spending” excludes the Big 3 entitlements: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. For comparison, in FY2011 those three programs combined will spend $1,493 B, while all other mandatory programs combined will spend $615 B. So while other mandatory is a whole lot of money, it’s small relative to the Big 3. And the Big 3 are the source of future spending growth, not other mandatory.

Under current law the biggest components of other mandatory spending are the low-income support programs (aka “welfare”, $280 B this year combined): cash welfare, food stamps, earned income tax credits, etc. Federal employees’ retirement is big ($146 B this year), and this year unemployment insurance payments are huge ($129 B). Other big chunks are veterans’ benefits ($78 B) and agriculture subsidies ($16 B).

The President provides a savings target for the other mandatory category but offers no specifics, other than to say proposals from the Bowles-Simpson Commission “and other bipartisan efforts … should be considered.”

Budget credibility: Zero. Without specifics, or at least per program targets (e.g., $X B from farm subsidies, $Y B from federal retirees), this is just pulling numbers out of thin air.

Discretionary spending

He is proposing additional cuts to defense and security discretionary spending. Details are TBD.

On the non-security side it appears he simply takes the new appropriations deal and extends it for ten years. But while he claims $200 B in non-security discretionary savings over 10 years in addition to the $400 B in savings from the President’s budget, it appears that he is relabeling what has already been decided in the recent appropriations deal.

As a policy matter this is smaller and therefore less important than the other changes listed above, but it’s a political flashpoint. Reporters should ask the Administration and CBO how the President’s new non-security discretionary spending proposal compares to a straight extension of the new FY11 appropriations soon-to-be-law. It’s even possible that he is proposing to increase spending and, in effect, “undo” some of this year’s deal in future years. We can’t tell until we see this comparison.

Budget credibility: Since discretionary spending totals can be enforced by spending caps that have a long history of enforceability, credibility here is fairly high. Unlike for “other mandatory” spending, you don’t really need to propose specifics to establish a credible and enforceable path for future discretionary spending. At the same time, you should be very skeptical of the presentation of the claimed non-security “savings.” This appears to be a misleading presentation. It looks like they are cutting only defense/security discretionary.

Analysis

Here are four broad reactions to the new proposal.

First, this is a short-term budget, not a long-term budget. There are three forces driving our long-run government spending and deficit problem:

- demographics;

- unsustainable growth in per capita health spending; and

- unsustainable promises made by past elected officials, enshrined in entitlement benefit formulas.

The President’s proposal addresses none of these forces. It instead spends most of its effort on everything but those factors. His proposed Medicare and Medicaid savings, while large in aggregate dollars, are quite small relative to the total amount to be spent on those programs, and he lets the largest program in the federal budget (Social Security) grow unchecked. While Bowles and Simpson focused their efforts on the major entitlements and also addressed other spending areas and taxes, the President’s proposal does the reverse, focusing on other mandatory spending, taxes, and defense. That’s a short-term focus.

Second, this proposal “feels” to me like the recently concluded discretionary spending deal. It’s the size of a typical deficit reduction bill that Congress usually does every five or so years. I’m sure the affected interest groups are even now preparing to invade Washington to explain how a 3-5% cut will devastate them. The problem is that our fiscal problems are now so big that they require much larger policy changes.

Third, while framed as a centrist proposal, the substance leans pretty far left. It’s deficit reduction through (triggered) tax increases on the rich, plus defense cuts, plus unspecified other mandatory cuts and process mechanisms that might cut Medicare provider payments. Centrist Democrat proposals do all of these things, but they also reform Social Security and Medicare, usually through a combination of raising the eligibility age, means-testing, and raising taxes.

Fourth, the President’s speech was campaign-like in its characterization of and attacks on the Ryan plan.

The President’s proposal could be the opening bid in a negotiation with Congressional Republicans. When you combine this substance with the President’s aggressive partisan attacks and framing of the Ryan budget, however, it’s hard to see how this leads to a big fiscal deal this year or next. A small incremental bill, which “cuts” spending by a couple hundred billion dollars over the next decade, is possible. But the chances of a long-term grand bargain in the next two years just plummeted from an already low starting point.

Why the debt limit fight will be different

The following is based on my experience working on maybe 8-10 debt limit increase laws from both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Both a debt limit increase and a continuing resolution are typically considered must-pass bills. If a must-pass bill is not enacted into law, something very bad happens, such as a government shutdown or the U.S. government defaulting on a debt payment.

Must-pass bills are incredibly tempting for Members of Congress (and outside advocates). Because most bills never become law, everyone wants to attach their desired policy change to a must-pass bill.

Bills to increase the debt limit are always terrible for Congressional leaders and the White House, because they have to get done but no Member wants to vote for them. Traditionally, the majority party (in each body) delivers most of the aye votes and the members of the minority free ride and vote no. That could betricky this year with a Republican House and a Democratic Senate.

Congressional Republicans are excited to use a needed debt limit increase bill as leverage to get additional spending cuts or budget process reforms, as they did with the FY11 appropriations bill.

I can think of at least three reasons why the debt limit fight should differ from the recently concluded battle on FY11 appropriations.

First, a temporary continuing resolution has a hard deadline, while a debt limit increase does not. Everyone knew that if no agreement was reached and no new CR was enacted by midnight last Friday, the government would shut down at that moment. That precise deadline created pressure on both sides to make decisions.

The debt limit works differently. You have to increase the debt limit, but there isn’t a precise deadline. Treasury has tools to manage its cash and borrowing from financial markets. There are tricks Treasury can use to dip into other, special purpose emergency reserves of cash (or other borrowing authorities) so that the debt subject to limit doesn’t increase quite as quickly as under normal operations.

From a financial management standpoint, each of these tricks is bad policy. As an example, you shouldn’t take cash from the Emergency Stabilization Fund and pay normal government bills with it. The cash in the ESF is there in case there is a currency crisis. Treasury doesn’t want to do these tricks, and they shouldn’t. But if the alternative is defaulting on debt issued to the financial markets, it’s not a hard call. You do the bad cash management policy until you get the new law. Treasury has done this before, in both Republican and Democratic Administrations.

Some of these tricks can buy Treasury days, and a couple of them can buy them weeks. In extremis, Treasury can go for a few months past when they’d like to go. They begin with the least damaging techniques, and work their way to more damaging ones as needed. Treasury hates doing this, and the Secretary of Treasury will quite justifiably complain that he is being put in the position of doing bad policy and damaging American credibility in financial markets.

There is a measurable cost to this delay. The ongoing uncertainty and the acrobatics Treasury would be performing could cause investors to charge the government a higher risk premium for borrowing. This damaging effect could continue even after legislation is signed into law.

Members of Congress who are battling over debt limit legislation need to understand:

- Unlike the CR, the Executive Branch will not be able to give them a precise drop-dead date, only a range;

- There is flexibility on the back end of that range; but

- Using that flexibility is bad policy and carries a real economic and financial cost.

Second, defaulting on a debt obligation is potentially far more serious than a temporary government shutdown. The damage is also more dispersed and harder to understand than troops not getting paid and national parks shutting down. All the financial market and economic policy types (including me) are terrified of running out of room because it’s never happened before and the worst case scenarios are really, really bad.

Toward the end of the appropriations negotiations, it was conventional wisdom that none of the leaders wanted a shutdown. Mutliply that X1000 for a failed debt limit increase. They have to get it done, somehow, and Treasury will have to do whatever is legal and necessary to buy time if negotiations bog down.

These two factors interact. You have to increase the debt limit, just not by any specific moment. That makes the legislative negotiating dynamic very different from the appropriations negotiations.

Third, a freestanding debt limit increase bill doesn’t contain any spending cut, so there is no “natural” fiscal policy that should obviously included.

In contrast, the just-concluded spending fight was about appropriations bills. It therefore made procedural and negotiating sense to try to cut the discretionary spending contained within those bills. Democrats attacked Republicans for focusing all their attention on cutting a relatively small portion of the spending pie, but that portion was what Democrats had left unfinished from the prior year. At Democrats’ insistence, some mandatory spending cuts were substituted in place of discretionary cuts, but the scope of negotiation was fairly well constrained to things already in the bill.

On a debt limit bill, a fiscally conservative House majority has more leeway to include anything its members think “should” be linked to a debt limit increase. This added flexibility can be a blessing and a curse for those managing the process. Since there are no natural subject matter boundaries, individual Members or groups can and, I assume will, show up with all sorts of policy changes they believe should be packaged with a debt limit increase.

It’s not obviously apparent (at least to me) that any of these three differences between debt limit legislation and appropriations particularly advantage one side or the other in the upcoming negotiation. The lack of a hard deadline tends to weaken the Executive Branch’s hand relative to the Legislative Branch, but mostly it just makes everyone’s jobs harder because there’s no clear deadline to force decisions.

The far more severe potential impact of a failed debt limit increase is a double-edged sword. It increases pressure on the leaders and provides leverage to rank-and-file Members willing to vote no. The President and Speaker Boehner both clearly wanted to avoid a government shutdown and were willing to compromise to avoid it. Some of their Members were more willing to take the risk of a shutdown, or did not feel the responsibility for the outcome, but only for their individual vote. This difference will be significantly amplified for a debt limit negotiation, making the leaders’ and President’s job even more difficult in this next round.

(photo credit: Ninja M.)