Congressional Republicans’ strategic shift on taxes

For months a common story line in the budget debate has been that a bipartisan deficit reduction deal was impossible as long as Republicans refused to raise taxes. President Obama, Congressional Democrats, and many observers asserted that it would be impossible to solve the deficit problem until and unless Republicans agreed to raise taxes. They further argued that if a deficit reduction deal did not come together, Republican intransigence on this point would be the reason why.

The specific argument was that the deficit could only be reduced through a combination of spending cuts and tax increases. This logic was applied to the Super Committee’s $1.2 – $1.5 T deficit reduction target.

The argument that tax increases are necessary for deficit reduction is not arithmetically true – it is quite possible to completely and permanently reduce, or even eliminate, the budget deficit only by cutting spending. In fact it’s not all that hard to do.

It may, however, be legislatively true that in a politically balanced Washington like we have now, a bipartisan deal with Democrats that does not raise taxes is impossible because Democrats will not agree to deep spending cuts as long as Republicans refuse to raise taxes.

The stalking horse for this argument is Grover Norquist, head of the antitax group Americans for Tax Reform (ATR). ATR’s position is that total federal income tax revenues should not be increased. A deficit reduction package consistent with ATR’s position could increase taxes, it just couldn’t increase income taxes. It could eliminate income tax deductions and credits, but to be consistent with ATR’s view, the higher income tax revenues that result would need to be used in full to cut income tax rates, so that the total income tax burden did not increase. (I use the phrases “total income taxes” and “net income taxes” interchangeably.)

Many DC Democrats argued that Mr. Norquist was really in charge, and that Congressional Republicans were unwilling to cross ATR for fear of political retribution. If there was no deficit reduction deal, we were told, it would be because Grover Norquist, Americans for Tax Reform, and Congressional Republicans all refused to agree to net income tax increases.

The most significant element of the failed Super Committee negotiation is that Republicans offered to cross the no-net-tax-increase line in exchange for structural entitlement reform or structural tax reform and a permanent answer on tax rates. The six Super Committee Republicans proposed a deficit reduction package that would increase net income taxes by about $250 B, plus another $40ish B in higher revenues that would result from correcting the way that inflation is measured. When you add in other “receipts” (which are technically different from tax “revenues”) from auctioning telecommunications spectrum, raising defined benefit pension fees, and asset sales, plus the dynamic effects of high revenue resulting from greater GDP growth (as scored by CBO) that would result, the “tax” (technically, non-spending) component of the Super Committee Republican offer was in the $500 B ballpark.

The six Super Committee Republicans made two offers to Super Committee Democrats:

- We will agree to these tax increases if they are packaged with structural entitlement reforms like the premium support system for Medicare assumed in the House budget resolution and if these tax rates are made part of permanent law; or

- We will agree to these net tax increases if they are part of a pro-growth tax reform that permanently lowers marginal income tax rates and if they are packaged with significant reductions in entitlement spending growth through incremental, non-structural changes.

This is a stunning move, as almost all Congressional Republicans had previously been unwilling to increase net taxation. Speaker Boehner signaled his willingness to cross the line in his Grand Bargain negotiations last summer with the President. Senator Tom Coburn proposed something similar over the summer, and first crossed the line when he tried to repeal/dial back the ethanol tax credit without using the revenues raised to cut other taxes. Now the rest of Congressional Republicans (or at least the six key Rs on the Super Committee) have joined them. That is a fundamental shift in the budget debate.

The details of the second Republican offer are significant. The SC Republicans proposed to lower marginal income tax rates while increasing average income tax rates. They proposed to eliminate income tax deductions and credits, use some of the revenues raised to lower tax rates, and use some of the revenues raised to reduce the deficit. It’s this last part that is new and extraordinary coming from Congressional Republicans.

This Republican shift means that the earlier narrative that deficit reduction is impossible because Republicans refuse to raise taxes is now invalid. It also invalidates the argument that Congressional Republicans refuse to cross Grover Norquist and Americans for Tax Reform. As best I can tell, the Republican offer is inconsistent with ATR’s position.

I have mixed feelings about this strategic shift:

- As a policy matter I hate it. I don’t want to raise any net taxes, period. I strongly prefer to reduce the deficit only by cutting spending, and I fear that in the long run the higher revenues will be used not to reduce the deficit, but instead to finance higher government spending. My biggest concern is that Congressional Republicans might trade permanent tax increases for only temporary cuts in spending growth. If they do, then we will repeat this dynamic several years down the road, only from a starting point of bigger government.

- I recognize that legislating in a politically balanced Congress forces compromise, and that one often has to accept things one hates in pursuit of a larger goal. I assume the Republican negotiators thought that this was both the best deal they might get, and that it was better than simply kicking the deficit can down the road another year. Based on what I know of the six Super Committee Republicans, Speaker Boehner, and Senator Coburn, I think most if not all of them hate net tax increases as much as I do.

- This shift should advantage Republicans as they compete for the hearts, minds, and votes of those centrists and moderate Democrats who think that spending cuts must be accompanied by tax increases.

Having lost their principal line of attack, the President’s team and Congressional Democrats have therefore moved to two fallback arguments:

- Republicans would not raise taxes enough; and

- Republicans refused to raise taxes on the rich.

Over the next year you will often hear the word “balance,” implying that there is some substantive or moral equivalence between the particular tax increases that Democrats want and the entitlement spending cuts that are arithmetically necessary to solve our long-term deficit problems. I reject the balance concept and its underlying logic, but what’s more important is that you understand the linkage between the balance argument and the earlier, now invalid, line of attack. Every time you hear “balance” as a critique of the Republican position, you should think “DC Democrats are conceding that Republicans have put net tax increases on the table. They just want bigger tax increases and smaller spending cuts than Republicans offered.”

The second argument, that Republicans refuse to raise taxes on the rich, is now incorrect. The Super Committee Republican offer would not just have increased net taxes, as well as net income tax revenues. It also would have increased taxes paid by those with incomes over $200,000. The reform proposed by Super Committee Republicans would have resulted in net tax reductions for income classes below $200,000, and net tax increases for income classes above $200,000 (and above $100,000 by 2021). It would have made the tax code more progressive than it is today.

The net tax cuts for lower and middle-income taxpayers would result from the Republicans’ proposed rate cuts. The net tax increases for upper-income taxpayers would result from eliminating tax deductions and credits that disproportionately affect “the rich,” and that would more than offset the revenue lost to the government by cutting top marginal rates. In effect, the Super Committee Republicans proposed that the rich pay higher taxes as part of a deficit reduction package, while lowering the marginal tax rates that all income taxpayers would face, to get the incentives to work and invest right.

The tax attacks on Republicans therefore look like this:

Republicans refused to raise taxes as part of a deficit deal.No longer valid.Republicans refused to buck Grover Norquist and Americans for Tax Reform.Invalid.Republicans refused to raise taxes on the rich.No longer valid.- Republicans would not raise taxes enough.

- Republicans would not raise taxes on the rich enough.

As you follow the deficit reduction debate over the next year, it will be important to remember how significantly the Super Committee Republicans changed the negotiating playing field during these negotiations, and how their offer has changed the nature of the fiscal policy debate.

(photo credit: Sesame Street

The President’s missed opportunities for deficit reduction

In today’s press briefing White House Press Secretary Jay Carney discussed the Administration’s efforts to encourage Europe to address their ongoing debt crisis:

As you know, Matt, with the President and Tim Geithner — Secretary of Treasury — and others have been very engaged with their European counterparts on this issue, offering advice because we have a certain amount of experience in dealing with this kind of crisis. And we urge them to move forward rapidly.

In the same briefing Mr. Carney discussed the President’s role in the Super Committee:

The President, at the beginning of the process, at the beginning of the super committee process, a committee established by an act of Congress, put forward a comprehensive proposal that went well beyond the $1.2 trillion mandated by that act and was a balanced approach to deficit reduction and getting our long-term debt under control.

Mr. Carney then turned to the failure of the Super Committee:

This committee was established by an act of Congress. It was comprised of members of Congress. Instead of pointing fingers and playing the blame game, Congress should act, fulfill its responsibility. As for the sequester, it was designed, again, in this act of Congress, voted on by members of both parties and signed into law by this President, specifically to be onerous, to hold Congress’s feet to the fire. It was designed so that it never came to pass, because Congress, understanding the consequences of failure, understanding the consequences of inaction, the consequences of being unwilling to take a balanced approach, were so dire.

Now, let me just say that Congress still has it within its capacity to be responsible and act. As you noted, the sequester doesn’t take effect for a year. Congress could still act and has plenty of time to act. And we call on Congress to fulfill its responsibility.

… What Congress needs to do here has been and remains very clear. They need to do their job. They need to fulfill the responsibilities that they set for themselves.

The President’s press secretary tells us that the President and his Treasury Secretary have “been very engaged with their European counterparts” in addressing their debt crises, but it appears the President’s involvement in the American Super Committee was to set a proposal on the table and then leave.

Mr. Carney points to the President’s September proposal to the Super Committee, and to the negotiations with Speaker Boehner over the summer, as evidence that the President is trying to reduce the budget deficit. For balance I think it’s important to point out five deficit reduction opportunities the President missed.

- Democratic majorities (2009-2010): For the first two years of his term, the President had partisan super majorities in the House and Senate. There was neither a Presidential proposal to reduce the deficit, nor any legislative action on deficit reduction. The Administration argued that deficit reduction would be inconsistent with the short-term need for macro fiscal stimulus, even if that deficit reduction were to start several years down the road.

- Bowles-Simpson (Fall 2010 – Feb 2011): The President could have taken the bipartisan Bowles-Simpson recommendations from the commission he created and proposed them in his budget. Instead he shelved those recommendations.

- Blasting Paul Ryan and the Ryan budget (Spring 2011): After House Republicans proposed $4 T of deficit reduction, the President offered a new budget that he claimed would match this deficit reduction, but which fell more than $1 T short and which relied on unspecified tax increases for the bulk of its claimed deficit reduction. More importantly, in rolling out his proposal the President personally blasted House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan and the Ryan budget, framing his new deficit reduction proposal as part of an aggressive political attack on Congressional Republicans.

- Backtracking in the Grand Bargain negotiations (Summer 2011): When the Gang of Six offered their proposal in the middle of the Obama-Boehner negotiations, the President increased his demand for tax increases by $400 B over what he had previously proposed. How could Speaker Boehner then sell his Republican Members on a deal that was worse than the President’s previous offer? This Presidential step backward caused the Grand Bargain negotiations to collapse.

- Phoning it in to the Super Committee (Fall 2011): The President was literally phoning it in (from Hawaii) to the Super Committee. His advisors were nowhere to be found in or near any of the SC negotiations. As best I can tell, only two of the six Super Committee Democrats (Senators Baucus and Kerry) were actively involved in negotiating with the six SC Republicans, and those two had no political cover from the President. Today, after the Committee’s failure was formally acknowledged, we can see the President’s press secretary doing everything possible to distance the President from this failure and blame Congress for it.

Might the Super Committee have succeeded had the President been “very engaged” with Congressional negotiators, as Mr. Carney says he is with European leaders? I don’t know, but I am a bit surprised that Mr. Carney is so quick to emphasize the President’s active involvement in addressing Europe’s fiscal problems, while not even pretending to care about a related American effort.

Mr. Carney says that “Congress needs to do their job. They need to fulfill the responsibilities that they set for themselves.”

Q: In a politically balanced Congress, is significant deficit reduction possible without Presidential leadership or even involvement?

(photo credit: The White House)

The political risks of targeted mortgage subsidies

Yesterday the President announced an expansion of a program to help some homeowners who are underwater on their mortgages. The President announced his new policy in Nevada, one of the four “sand states” where the housing bubble grew biggest. The others are California, Arizona, and Florida.

Yesterday I wrote:

Mortgage refinancing policies are quite hard to do at scale. If recent history is a guide, this program may help a few tens of thousands of homeowners. That’s a trivial macroeconomic impact. Even if it does help 900,000 homeowners, the effects will be small enough that they won’t show up on most macro forecasts. Its greater benefit may be political: it creates another talking point for the President.

The President can contrast his action with a Congress that is blocking his broader legislative proposal. The developing Beltway conventional wisdom seems to be that while the policy benefits of this new proposal are at best small, this is unquestionably a useful political weapon for the President.

The specific policy action he is taking, however, also carries downside political risk for the President that may not be obvious at first glance.

Many elected officials have a bias toward government action: they see a problem and ask “What can we do to fix it?” The solutions they embrace often arise from an iterative process in which advisors compare the problems that exist with the policy tools available to address them and make the best possible match.

These matches are almost always highly imperfect, especially when you’re working on housing. Let’s look at two key attributes of the President’s new policy:

- It will subsidize only a small share of homeowners. For each newly subsidized underwater homeowner there will be many more who are, or feel like they are, in a similarly deserving situation and yet will not received subsidized aid. If we give the President maximum credit for helping “up to” 900,000 homeowners, that’s about 1 in 80 homeowners, of which there are about 75 million in total. The actual ratio will likely be much worse.

- Since assistance will be targeted by a set of rules, some of those who receive aid will be those whom, upon closer examination, most would deem “undeserving.” This program helps those with a high loan-to-value ratio, which can occur either because the house’s value has declined, or because the homeowner took out or refinanced into a particularly big mortgage. While we may have sympathy for those in the first category, the homeowner who at the peak of a regional housing bubble withdrew equity from his mortgage to buy a big boat and was then hit by a housing price decline evokes far less sympathy. And if he now receives taxpayer subsidies, his neighbors are going to be ticked.

These policy features create political risk that the President’s team may be discounting or even ignoring. It is fairly easy to focus press attention on the hard luck case of a responsible homeowner who, through no fault of his own, was hit by regional housing price declines and is now locked into an underwater mortgage.

But government action to help that sympathetic homeowner will leave many more without similar aid, and if past experience is a guide, some of them will be angry at the inequities created (real or perceived). If the expanded program also results in high visibility cases of subsidized big spenders who gambled on the housing bubble by withdrawing equity, a backlash could grow.

Whatever your views on the policy merits of placing additional taxpayer funds at risk to subsidize underwater homeowners, it is a political mistake to pay attention only to the one homeowner you’re helping, and to ignore possible pushback from the 79 or more homeowners you’re not helping, as well as from the taxpaying renters.

I am not predicting a major political backlash on the President’s new policy announcement. I think it’s too small to have either a large policy or political effect, positive or negative. I want simply to remind you that a program like this is not all political upside for the President. Don’t forget that the original February 2009 Rick Santelli explosion, which launched the Tea Party, was a reaction to an Obama Administration proposal to use taxpayer funds to subsidize targeted mortgage relief.

(photo credit: Mark Nicolson)

Democracy is SO inconvenient

In anticipation of today’s mortgage refinancing policy announcement in Las Vegas, White House Communications Director Dan Pfieffer writes:

Using the mantra “we can’t wait,” the President will highlight executive actions that his Administration will take. He’ll continue to pressure Congressional Republicans to put country before party and pass the American Jobs Act, but he believes we cannot wait, so he will act where they won’t.

Mantra? That’s a signal to the President’s political allies: please repeat this phrase.

The new policy will allow some homeowners who are underwater on their mortgages to refinance at lower interest rates. It does this by waiving some fees and shifting a bit of incremental risk to taxpayers through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are now in effect wholly-owned subsidiaries of the U.S. government.

This is an incremental expansion of an existing housing refinance program. If effective, it will help some more underwater taxpayers with fixed-rate mortgages, at some risk of increased cost to taxpayers. The Administration is using phrases like “may help up to 900,000 homeowners.” Key words are may and up to.

Mortgage refinancing policies are quite hard to do at scale. If recent history is a guide, this program may help a few tens of thousands of homeowners. That’s a trivial macroeconomic impact. Even if it does help 900,000 homeowners, the effects will be small enough that they won’t show up on most macro forecasts. Its greater benefit may be political: it creates another talking point for the President.

If this were a huge program that would help several millions of underwater mortgages at an enormous cost to the taxpayer, there would be some interesting policy tradeoffs worth exploring. In particular, are the macroeconomic benefits of helping these homeowners refinance and potentially escape from their underwater mortgage worth the increased costs to the taxpayer and the inequities created in which one group of Americans subsidize others whose

I am more intrigued by the President’s new mantra, “We can’t wait.” The logic is “We can’t wait for a Republican Congress, so we’re acting with every tool we have to improve the economy. We admit it’s not enough, but that’s [Republicans in] Congress’ fault.” Never mind the near-comatose Democratic-majority Senate that is neither marking up the President’s proposals in committee nor taking up alternative House-passed economic growth bills.

The President’s argument is, in effect, “We can’t wait for democracy.” The Constitution gives the power of the purse to the Congress, not the President. If the Congress doesn’t want to enact his proposals, then it shouldn’t, and that’s how the system is supposed to work.

I am not surprised that the President is using the legislative flexibility he has to maximum effect. I am a bit surprised that he sees a political benefit in framing himself as an Imperial leader who can and should ignore democratic processes. This seems inconsistent with Democratic party rhetoric in recent years.

Democracy is so inconvenient when your party controls the Presidency and the opposition can block your legislative agenda.

(photo credit: JD Hancock)

Three silly stimulus arguments

Here are responses to three silly stimulus arguments I hear frequently.

Argument: This fiscal stimulus will increase economic growth and create jobs.

Response: As John Taylor points out, even if you believe this, you can’t forget the word temporarily. The Administration refuses to produce their own estimates of the projected impact of the President’s new stimulus proposal, presumably because they burned themselves with their January 2009 estimate of the first stimulus. They are instead leaning heavily on two private forecasts, by Macro Advisers and Democratic economist Mark Zandi. (I frequently use MA’s forecasts in my work.) The Administration forgets to mention that both these forecasts project only a temporary increase in GDP and employment growth from the President’s proposal. Both predict that with the President’s new stimulus proposal, the economy would be stronger than it otherwise would be in 2012, but weaker than otherwise in 2013 and 2014 after the new policies have ended.

Both forecast a decline of at most 1 percentage point in the 2012 unemployment rate. Many conservatives are skeptical the impact will be even that large.

Q: Should Congress enact a proposal that includes deficit-increasing policies of $450 B that will, at best, temporarily reduce the unemployment rate by one percentage point for one year? Whatever spending cuts and/or tax increases are enacted to offset this deficit increase could otherwise be used to reduce future budget deficits.

Argument: Temporary bonus expensing will help the economy grow.

Response: The same is true of temporary “bonus expensing,” in which Congress provides the ability for a firm to deduct from taxable income more business investment in the next year. Like the President’s proposal, this is a timing shift. As a temporary proposal, it would accelerate business investment into 2012 that would otherwise occur in 2013 and 2014.

If we were only looking at a projected one-year dip in GDP and job growth, then it might make sense to “borrow” growth from future years and bring it into 2012. But when the projection is for slow growth over the next few years, these timing shifts don’t help unless you’re up for re-election in 2012.

I like the idea of permanent expensing of business investment. Given current forecasts of slow economic growth over the next few years, I don’t see what is gained by this temporary timing shift.

Argument: Austerity measures will cause a fiscal contraction.

Response: Some on the Left argue that policies to address America’s expanding government and exploding budget deficits will cause a short-term fiscal contraction. They make a traditional Keynesian argument: the economy needs more fiscal stimulus now, and if we cut spending too much we’ll hurt the recovery. If you buy the traditional Keynesian fiscal stimulus argument, then this is indeed a theoretical concern.

This will never, ever happen, for both a policy and a political reason. Deficit-reducing policy changes are always phased in over time, and the scored deficit reduction from both spending cuts and tax increases grows (linearly) with time. The spending cuts and/or tax increases in the first couple years of a typical deficit reduction package are trivially small, a rounding error compared to a $15 trillion annual GDP.

And do you really think that politicians who are up for reelection next year (the President, 435 House Members and 33 Senators) will choose to concentrate policy and political pain in the next year by front-loading the spending cuts and/or tax increases? Even if the natural timing of deficit reduction legislation did not delay the fiscal impact, the self-preservation instinct of politicians eliminates any practical risk of a large deficit-reduction package harming the economy in the short run.

(photo credit: D’Arcy Norman)

The President’s third goal for tax reform: raise taxes

President Obama and his team have proposed five goals for tax reform:

- Cut rates

- Cut inefficient and unfair tax breaks

- Cut the deficit by $1.5 trillion over 10 years

- Increase investment and growth in the United States

- Observe the “Buffett rule.”

I want to focus on #3, which translates as “Raise taxes by $1.5 trillion over 10 years.”

I did a little arithmetic and found:

- That’s about a 4 1/2% increase in total federal taxation over current policy.

- It’s about a 0.9 percentage point increase in the share of GDP above current policy.

- In addition to comparing the President’s goal to current policy, we can compare it to what we have done in the past. Since current policy allows taxes to grow relative to the economy over time (mostly because of “bracket creep,”), the President’s goal would bring taxes to about 20% of GDP by the end of the decade (2021).

- Compared to the historic average of 18.1% of GDP, the President’s goal for tax reform would add almost two full percentage points of GDP to federal tax collections. While it’s about a 4.5% increase in total federal taxation over current policy, it’s about a 9% increase in total federal taxes relative to historic averages.

- Don’t forget that even when taxes stay constant as a share of GDP, real (inflation-adjusted) tax collections by the federal government grow. If you hold taxes constant at their historic average share of the economy, the tax bite will grow in absolute terms while staying constant in relative terms.

That third Presidential tax reform goal is a doozy. I think a tax increase that large has a bigger negative economic impact than any good you might be able to do through making the tax code more efficient. The President’s goal of raising taxes undermines his goal of increasing investment and growth.

(photo credit: White House photo by Samantha Appleton)

A past Suskind error

I wish I didn’t have to write this post, but I feel obliged to do so.

Reporter Ron Suskind has a new and quite critical book about the Obama economic team and the Obama White House. I am not linking to it because I am not recommending it. While I often differ with the current team’s approach to economic policy, I do not take Mr. Suskind’s reporting seriously because of my own experience.

Mr. Suskind wrote another book about Presidential economic advisors during the Bush Administration, focusing on Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill’s perspective. In that book Mr. Suskind describes a meeting of President Bush with his economic advisors in November of 2002. This was the meeting at which the President’s advisors debated whether the President should propose a new tax cut bill in early 2003 (he did). (President Bush also fired Secretary O’Neill in December 2002.)

Mr. Suskind gets some of the details right – the meeting was in the Roosevelt Room, he has the correct list of attendees, and he captures some of the substance and flavor of the debate.

He then includes a paragraph-long quote he claims I said to the President. In that quote (in quotation marks), Mr. Suskind wrote that I argued in favor of doing the tax cut, and that I was therefore rebutting Secretary O’Neill and two other Cabinet-level advisors.

I did favor the tax cut, but the quote Mr. Suskind attributes to me is fabricated. I didn’t say anything even remotely similar to what he quoted me as saying, and I didn’t make a recommendation in that meeting. I know this with certainty because this was the first big Presidential meeting in which I had a significant speaking role, and I was, to say the least, nervous.

I was at the time a White House “deputy,” one big notch below the Cabinet officials and senior White House advisors who were debating what the President should do. My role in that meeting was to be the honest broker staffer who walked the President through the numbers and policy options. I was entirely focused on that task.

Had I weighed in on one side of the debate, I would have undermined my honest broker role and also undercut my boss, NEC Director Larry Lindsey. It was my role to present the facts, numbers, and options as neutrally and accurately as possible, and Larry’s role to debate with Secretary O’Neill and others. Having been in the job only three months, I was also nervous enough that I would not then have challenged a Cabinet Secretary in front of the President, much less several.

It’s a small point, and something that only I would notice. Neither Mr. Suskind nor anyone else affiliated with the book had contacted me about the quote before publication, and indeed I never interacted with the author until I met him accidentally several years later.

Had the book purported to characterize my view, rather than actually quoting me, I might have shrugged it off. But when you see a fabricated, unverified quote attributed to you in a book that claims to be a historical description of an important policy meeting with the President, it sticks with you.

Mr. Suskind’s earlier book about the Bush Administration was an inaccurate and unfair depiction of the President and the advisors for whom I worked, and of the White House in which I worked. It was clearly fed by a disgruntled former Presidential advisor promoting himself and pushing his own agenda.

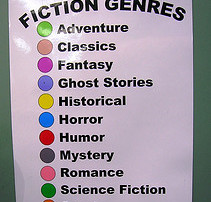

I will assume the same about his latest. Amazon should move it to the Fiction category.

(photo credit: Enokson)

Good CEOs plan ahead

Here is the President speaking today in Cincinnati:

THE PRESIDENT: We already cut a trillion dollars in spending.

[My plan] makes an additional hundreds of billions of dollars in cuts in spending, but it also asks the wealthiest Americans and the biggest corporations to pay their fair share of taxes.Now, that should not be too much to ask. And by the way, it wouldn’t kick in until 2013. So when you hear folks say, oh, we shouldn’t be raising taxes right now — nobody is talking about raising taxes right now. We’re talking about cutting taxes right now. But it does mean that there’s a long-term plan, and part of it involves everybody doing their fair share.

The problem with the President’s argument is that good CEOs plan ahead. When they think about whether to hire a new worker, buy a new piece of equipment, or build a new factory, they plan over a horizon that’s longer than just the next 15 months. A tax increase enacted into law now, to take effect in 2013, is only slightly less discouraging to economic growth than a tax increase that takes effect immediately. A CEO who knows her firm’s taxes will increase in 2013 will be discouraged from hiring, investing, and building now.

The President is right when he says that “there’s a long-term plan.” Unfortunately, that long-term plan involves higher taxes, and firm managers know that. Their horizon is not limited to the next election.

(photo credit: Thommy Browne)

Keep monetary policy independent

Yesterday the top four Republican Congressional leaders sent a letter to Fed Chairman Bernanke about monetary policy. I think that was a big mistake.

The letter weighed in on the Fed’s debate about monetary policy, and was sent by Speaker Boehner, Leader Cantor, Leader McConnell, and Whip Kyl. The key text is:

Respectfully, we submit that the board should resist further extraordinary intervention in the U.S. economy, particularly without a clear articulation of the goals of such a policy, direction for success, ample data proving a case for economic action and quantifiable benefits to the American people.

I’m not commenting today on the economic or substantive policy view the Leaders express, but instead on the process point. The U.S. has several long-standing economic policy advantages over many other countries. One of those advantages is a fairly apolitical monetary policy process. I think monetary policy is worse when it is influenced by political pressure from Congress or the White House. The Leaders’ letter is a clear attempt to apply pressure to the Fed.

The letter offers a commonly-expressed opinion about what the Federal Open Market Committee should (not) do. Coming from market participants, academic economists, or an editorial page, these views are perfectly appropriate and contribute to a vigorous policy debate.

But it’s different when such policy input comes from those who have the legal and political ability to harm or weaken the Fed. Even if elected officials don’t include “or else” in their policy statement (and the Republicans leaders did not), everyone knows that it’s implied to some degree. Monetary policy influenced by volatile political winds will be unstable and unpredictable over time. That’s bad.

The paradox is that if you’re an inflation hawk and agree with the substance of the Leaders’ letter, you should be a strong advocates for Fed independence and not sending such letters. In general political pressure from both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue will far more often press for looser monetary policy. The more effective Congress or the White House is at shaping Fed decisions, the greater the long-term risk of too-high inflation.

The Republican leaders aren’t the only ones pressuring the Fed. As the Wall Street Journal editorial page points out, House Financial Services Committee Ranking Member Barney Frank has his own strategy to push for looser monetary policy in the long run. He’s doing it indirectly by laying the groundwork for changing the makeup of the FOMC in a way that will lead to a more dovish monetary policy.

The Supreme Court metaphor is an apt one. Which is worse: Republican leaders sending a letter to the Supreme Court telling them how they think the Court should decide on a pending case, or a senior Democrat in Congress talking about legislatively restructuring the Court’s membership in a way that everyone knows will lead to more liberal justices over time? Both apply pressure to the Court’s decisions through implicit threats.

This metaphor isn’t perfect. The Constitution makes the Supreme Court a separate and equal branch of government, while an independent Fed is a Constitutional anomaly at best.

Update: A friend points out that Members of Congress frequently file amicus briefs in court cases. Yep, this metaphor is far from perfect.

I have no doubt that Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle will continue to weigh in on monetary policy. I wish they wouldn’t. Congress has plenty of fiscal policy problems on their plate, and their pressure on monetary policy undermines a long-term advantage of the American economic system.

(photo credit: Joe Hatfield)

A fundamental fiscal deception

I’d like to see if I can add a little more clarity to yesterday’s post about the President’s new budget proposals. In particular, I want to try to help you zoom out from specifics (like the war funding gimmick) and see what I think is a larger and more fundamental deception in the fiscal argument being made by Team Obama.

I think of this as a layered argument. These layers are nothing more than a mental model I’m using to keep my own thinking straight about this complex topic. The layers get progressively more egregious.

Layer 1 involves legitimate judgment calls about what to count, what not to count, and how to count it. This includes questions like “Should we count Medicare doc fix spending as part of this proposal,” and “Should we measure tax increases for the rich against current law or current policy?” These are budget judgment calls in which honest, well-intentioned budget wonks can and will reach different conclusions, and everyone else’s eyes will glaze over.

Layer 2 is about pure scoring gimmicks. There are two in the President’s new proposal:

- The war drawdown gimmick — the Administration is claiming deficit reduction credit for drawdown decisions in Iraq and Afghanistan that were made long ago.

- The past legislative action gimmick — the Administration appears to be claiming deficit reduction for spending cuts enacted over the past six months as if it is new. These spending cuts were contained in the spring’s Continuing Resolution law and the first round of spending cuts in the summer’s Budget Control Act. I say “appears to be claiming” rather than “is claiming” because they are very cleverly wording their claims. I get to this in layer 4.

While Layer 1 involves judgment calls and differences of opinion among budget wonks, layer 2 is dishonest budgeting, period.

Layer 3 expresses the effects of that dishonest budgeting in two ways: (a) the Administration’s claimed $4T of deficit reduction, and (b) their claim of balance between spending cuts and tax increases. No matter what your view on the items in layer 1, the Administration can only make these two very specific claims because of the gimmicks in layer two. These two claims are central to the President’s fiscal policy argument.

Layer 4 involves the too-clever word games. When pressed, Administration officials can correctly argue that their carefully-phrased language acknowledges the gimmicks in layer 2. The Administration isn’t technically lying to you — as I showed yesterday, they explicitly acknowledge the “including the $1 T of spending cuts already enacted” point, and while the President’s statements are highly misleading, they are also technically true. It’s just that almost nobody understands the artful phrasing that leads you to an incorrect conclusion that they don’t actually say.

Layer 5 is that the President’s plan and communications strategy appear predicated on this rhetorical misdirection. If you reject the budget gimmicks in layer 2, then the $4T and “balanced deficit reduction” claims are invalid, and the conclusions the Administration misleadingly allows you to draw (but technically doesn’t say) are flawed. I can’t see how this can be anything other than an intentional strategy centered on taking advantage of the reality that (almost) nobody understands all this budget stuff.

Most observers and press are focused on layers 1, 2, and 3(a). Almost everyone understands the war funding gimmick by now, so it comes up repeatedly in discussion. I think the problems go deeper — layers 4 and 5 bug me even more. Budget scoring is an arcane subject, and there are always judgment calls to be made. I have yet to see a budget (from either party) that doesn’t contain at least a few questionable scoring calls and gimmicks, most of which are secondary to the real hard policy choices made in the rest of the budget. In this case, however, the President’s argument rests on scoring gimmicks that are indisputably dishonest. And there’s no way that can be an accident.

It appears Team Obama wants you to conclude that there is no difference between the President and Congressional Republicans on the amount of proposed deficit reduction, and that the President wants a prospective deficit reduction approach balanced between spending cuts and tax increases. Both conclusions are false. The policy changes the President is proposing are significantly less deficit reduction than that proposed by (House) Republicans, and almost all of the President’s new proposed deficit reduction comes from tax increases.

To put the second point in schoolyard terms, President Obama is in effect saying to Republicans, “We did it all your way (spending cuts) the last two times, so this time we should do it almost all my way (tax increases). That’s balanced.”

It’s a legitimate liberal policy position to propose new net deficit reduction of about $1.4 T over the next ten years, almost all of which comes from tax increases on the rich. That is the President’s policy. I think it’s terrible policy, but that’s a judgment for the Congress and ultimately for American voters to make.

Team Obama knows they will lose the public debate if they actually say that, so they are helping you to draw mistaken conclusions about what they are actually proposing. They are instead pretending to propose $4T of deficit reduction over the next ten years, balanced between “real, serious spending cuts” and tax increases.

That is a fundamentally dishonest presentation of the policies the President is actually proposing.

(photo credit: Steven Depolo)