The ratio of spending cuts to tax increases in the President’s budget

The Obama Administration claims their new budget contains $2.50 of spending cuts for every $1 of tax increases. Here is White House Chief of Staff and former Budget Director Jack Lew on Meet the Press yesterday:

We’ve seen from Republicans in–particularly Republicans in the House, but with Republicans generally, that they don’t want to be part of any plan that raises taxes at all. The president’s budget has $1 of revenue for every $2 1/2 of spending cuts. This can be done, but it can only be done when we work together.

Their 2.5:1 ratio is bogus. The President’s team is (1) playing a timeframe game and (2) counting interest savings from tax increases as spending cuts.

Contrary to Mr. Lew’s assertion, the President is proposing at least $1.20 of tax increases for every dollar of proposed spending cuts. The President’s budget locks in historically high spending levels and relies more on tax increases than spending cuts for the limited deficit reduction it proposes.

Table S-3 from the newly released President’s Budget starts measuring deficit reduction a year ago, in January 2011. The table shows $5.3 T of deficit reduction over the next ten years resulting from a combination of laws enacted last year and the President’s new proposals released in today’s budget.

The President’s budget is a set of policy proposals for the future. When most people hear the “The President’s budget has $1 of revenue for every $2 1/2 of spending cuts,” they think this ratio applies to the changes the President proposes for the future.

I will therefore split the OMB table and recalculate this ratio, ignoring spending cuts and tax increases that have already been enacted into law and looking only at future policy proposals. I argue this is the right way to do this ratio. Like the OMB table, this one shows deficit reduction for the next 10 years ($ in billions, 2013-2021).

|

Already enacted |

New proposals |

Total |

|

| spending cuts |

1720 |

1254 |

2974 |

| tax increases |

1510 |

1510 |

|

| interest effects |

800 |

||

| total deficit reduction |

1720 |

2764 |

5284 |

| spending / taxes |

0.83 |

2.50 |

|

| taxes / spending |

1.20 |

Looking only at new proposals, the President’s budget proposes 83 cents in spending cuts for each dollar it proposes in tax increases. Or we could say the President’s budget proposes $1.20 in tax increases for each dollar in proposed spending cuts.

The gimmicks

The President’s team is playing at least two games to generate their 2.5:1 ratio:

- They are cherry-picking their timeframe to make the ratio look at high as possible; and

- They are counting all interest savings as spending cuts.

Why did they start measuring in January 2011? Because that was the start of the Republican Congress, because last year only spending cuts were enacted, and because that timeframe maximizes the spending increase to tax cut ratio.

Good rule of thumb: if you cut government spending or raise taxes by $100 over the next ten years, you’ll also save about $20 in interest costs. These interest savings show up as reductions in government spending even when they result from tax increases. If, for instance, the President proposed no spending cuts and $100 B of tax increases, he’d get scored with $20 B of interest savings which would show up as reductions in spending. Using Team Obama’s logic that would count as a 5:1 ratio of tax increases to spending cuts even though common sense would suggest the ratio is infinite because the President isn’t proposing to cut any spending.

The right way to measure this ratio is therefore to exclude the interest effects and to measure only the ratio of deficit effects of proposed policy changes. The Administration counts interest savings from tax increases as spending cuts to inflate their ratio.

The Administration may also be playing games with how they define spending cuts and tax increases. I have not yet looked into their details on this point.

This ratio is a stupid measure

Even when it’s not distorted by games like these, the ratio of spending cuts to tax increases is a misleading way to analyze fiscal policy for two reasons.

- Both the numerator and the denominator measure a change rather than an absolute level. But for both spending and taxes the change that you measure depends on the starting point you pick. Even well-intentioned people can disagree on the right baseline from which to measure spending cuts or tax increases. In addition, it is easy to gimmick the starting point for either measurement to make the change look big/small as needed. Both the discretion involved in choosing spending and tax baselines and the opportunities for gimmickry mean that both the numerator and denominator of this ratio are at best somewhat arbitrary and at worst just made-up numbers.

- What kind of ratio of spending cuts to tax increases you should want depends not only on your fiscal policy views, but also on the starting point. Most people would say that if government spending is historically high then it makes sense to rely more on spending cuts than tax increases. Saying we need “a balanced approach to deficit reduction” and using this ratio (even when properly calculated) presumes the current starting point for policy is good or at least reasonable. With government spending starting way above the historic average that’s a huge assumption.

The political strategy of emphasizing this ratio

I think that by using this distorted 2.5:1 ratio, the President’s team wants you to conclude:

- that the President is a reasonable fiscal policy centrist who believes in reducing the deficit through a balance of spending cuts and tax increases;

- that his proposed balance relies much more heavily on spending cuts than tax increases; and

- that Congressional Republicans are therefore unreasonable and extreme for rejecting the President’s “balanced approach.”

When we look at the corrected ratio of $1.20 of tax increases for $1 of spending cuts, measured relative to a starting point of historically high government spending, we see the Obama Administrations actual fiscal strategy revealed.

- The short-term logic is, “Republicans got their spending cuts last year. Now it’s our turn to restore balance by relying mostly on tax increases to reduce future deficits.”

- The long-term goal is to lock in as high a level of government spending as possible and to rely principally on tax increases for deficit reduction.

- But since neither of these will sell to a center-right American public, they created a new way to measure this ratio and hope you won’t pay attention to the details.

Despite the Obama Administration’s rhetoric, the president’s budget relies more on tax increases than on spending cuts for the limited deficit reduction it proposes.

(photo credit: NBC News)

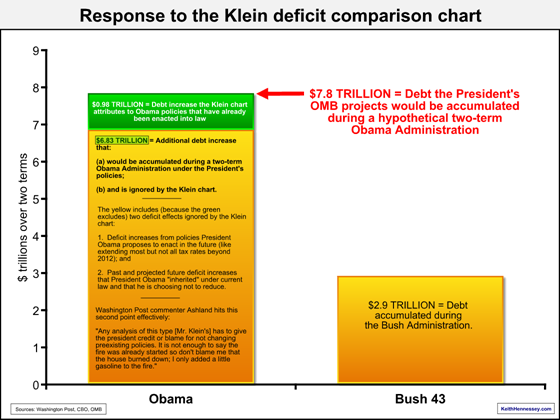

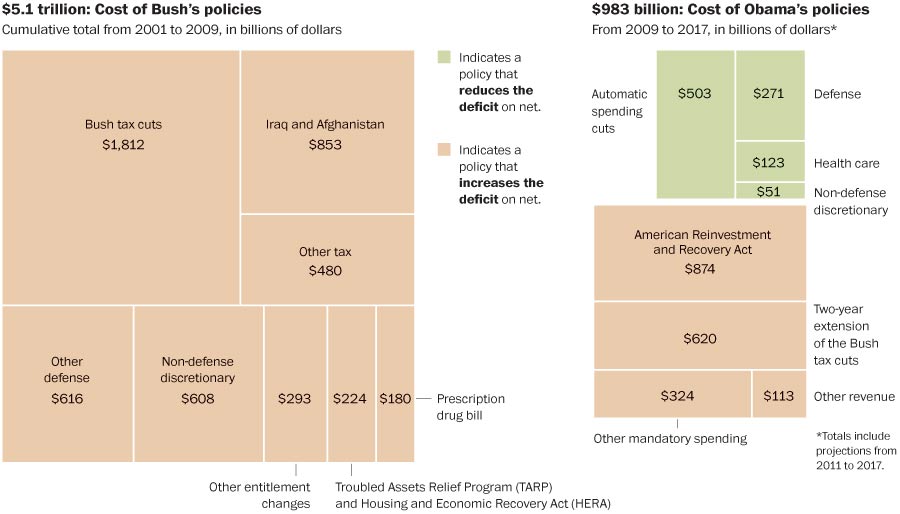

Data sources for response to the Klein deficit comparison chart

- All numbers measure changes in debt held by the public, the amount the federal government borrows from the rest of the world.

- Bush 43 debt increase over two terms: $2.9 T = $6.307 T – $3.410 T

- $6.307 T = “Debt to the Penny” from Treasury for 20 January 2009.

- Treasury provides “debt to the penny” but doesn’t go back to 2001, so I used OMB’s number for EOY 2000 from their Historical Table 7-1. That reflects the debt as of 31 December 2000, three weeks before the start of the Bush Administration. It errs just a smidge on the side of overstating the Bush debt increase.

- Obama debt increase over a hypothetical two Administrations: $7.8 T = $14.121 T – $6.307 T

- $14.121 T is OMB’s number for debt held by the public at the end of (CY, I think) 2016 under the President’s policies. That’s three weeks before the end of a hypothetical second term, so it errs just a smidge on the side of understating the Obama debt increase.

- $6.307 T is again Treasury’s number for 20 January 2009 (see the third bullet above).

- $0.98 T is from Mr. Klein’s chart. The residual, $6.83 T, is the $7.8 T total debt increase projected by the Obama Administration for the President’s policies over a hypothetical two terms, minus the debt increase that Mr. Klein argues results from policies proposed by President Obama and already enacted into law.

Response to the Klein deficit chart

A friend challenged me to respond to this chart and this post by Mr. Ezra Klein in the Washington Post:

Here is my response. You can click on the chart to see a larger version.

For those who care here are the sources I used in building the chart.

The President’s economic policy priorities

The President’s 2012 economic policy agenda emphasizes four policy challenges:

- the loss of American manufacturing employment;

- America’s dependence on oil;

- America’s sub-par (my phrase) education and training; and

- increasing income inequality.

Each of these trends began decades ago:

- Our employment has been shifting from manufacturing to services for decades, as it shifted from agriculture to manufacturing in the 19th century (all while American manufacturing output continues to grow over time);

- We have been dependent on oil as a fuel source for oh, about 100 years;

- The seminal report on American education, A Nation at Risk, was published in 1983, yet it reads as if it were written this year; and

- Income inequality has been increasing since about the 1970s, while even the spike in inequality at the very high end is probably 20ish years old.

There is nothing wrong with prioritizing long-term economic problems and challenges; in fact, quite the opposite. Washington usually focuses only on problems and challenges that will bite before the next election.

And yet:

- The President barely mentions the greatest long-term (and, increasingly, short-term) economic policy challenge we face, the size and growth of unfunded entitlement spending promises to the (current and future) elderly;

- The second greatest long-term economic policy challenge, closely related to the first, continues to be the unsustainable growth in per capita health spending, notwithstanding mistaken claims that the Affordable Care Act will slow that growth;

- The most urgent economic policy challenge we face is the slow recovery of the U.S. labor market, with housing weakness and macro/financial threats from Europe in a close second and third;

- In last year’s State of the Union address, President Obama framed the central policy challenge as infrastructure and public investment competition from China and India, something that doesn’t really make his top four this year (his manufacturing message is somewhat different);

- President Obama emphasizes frequently that he doesn’t want to “return to the policies of the past,” meaning the Bush era, yet these policies were not the cause of the problems he now stresses; and

- The President is not claiming that his proposed policies would solve even a significant portion of the problems he describes.

I would like instead to see the President set economic policy priorities like these:

- Clear out the barriers to private sector expansion and investment, in particular by reducing both the drags induced by recently enacted expansions of government and the massive uncertainty caused by lingering open policy debates;

- Stop trying to “fix” the housing market and let housing prices find a painful but market-clearing bottom so that more normal growth could resume;

- Make structural reforms to Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid that adapt them for inevitable demographic trends as well as evitable unsustainable promised benefit growth; and

- Aggressively expand international trade and investment rather than throw up protectionist barriers and rhetoric.

The massive recent and planned future expansions of government are the greatest threats to ongoing American economic strength in both the short and long term. Expanding the scope of government further as the President proposes will make things worse, not better.

(photo credit: Lawrence Jackson for The White House)

The President repeats the “blank check for autos” falsehood

Kudos to the Washington Post’s Charles Lane for his column debunking the President’s recent false claim:

THE PRESIDENT: In exchange for help — see, keep in mind, that the administration before us, they had been writing some checks to the auto industry with asking nothing in return. It was just a bailout, straight — straightforward. We said we’re going to do it differently.

In exchange for help, we also demanded responsibility from the auto industry. We got the industry to retool and to restructure. We got workers and management to get together, figure out how to make yourselves more efficient.

This “asking nothing in return … It was just a bailout, straightforward” claim is false.

A brief history of this false claim

President Obama’s former CEA Chair Austan Goolsbee first made this claim in June of 2009. The rebuttal I wrote then is the most detailed and specific debunking of this claim: Dr. Goolsbee gets it wrong on the auto loans. I’ll repeat the essential elements below.

President Obama’s former Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel repeated the false claim one year later. I responded, and Politifact rated Mr. Emanuel’s claim as false.

In September 2010 President Obama made this same claim. The Associated Press responded, demonstrating that the claim was wrong without explicitly labeling it as incorrect (wimps).

Both Politifact and the AP relied on my analysis, although their judgments are of course their own.

Now the President repeated this falsehood in his post-State of the Union tour this week and the Washington Post called him on it. Here’s Mr. Lane:

But in campaigning for re-election on this aspect of his record, he has shown an unfortunate, and remarkably ungracious, tendency to distort the record of his predecessor.

… President George W. Bush never gave the companies an unconditional bailout. He reluctantly loaned them money in return for what The Detroit Free Press described as “deep concessions” — and he did so in part so that Obama would not have to take office amid a full-blown industrial meltdown.

… On page 42 of his book on the bailout, former Obama auto-czar Steven Rattner praised the “thoughtful” Bush approach, noting that its “conditions–as imperfect as they were–provided a baseline of expected sacrifices that paved the way for our demands for give-ups from the stakeholders.”

What actually happened

In December 2008, after Congress left town without addressing this issue, President Bush had two viable options.

- He could allow market forces to work. GM and Chrysler would run out of cash by early January and a supplier run would begin sometime soon thereafter. The firms would begin liquidating in January with an industry-wide job loss we estimated at about 1.1 M jobs. This was during the late stages of the financial meltdown of 2008. In addition this choice would mean that about a month later President Obama would enter office facing not just a severely weakened economy and financial industry, but an in-progress collapse of the auto industry for which he would have no viable recourse.

- Or President Bush could provide a three-month “bridge loan” to allow President Obama time to get his feet set and decide whether he wanted to provide a longer-term loan to the firms.

President Bush chose the second option. In the final days of December Treasury loaned $24.9 B from TARP to GM, Chrysler, and their financing companies.

According to the terms of the loan (see pages 5-6 of the GM term sheet), by February 17th GM and Chrysler would have to submit restructuring plans to President Obama’s designee (and they did).

Each plan had to “achieve and sustain the long-term viability, international competitiveness and energy efficiency of the Company and its subsidiaries.” Each plan also had to “include specific actions intended” to achieve five goals.

- repay the loan and any other government financing;

- comply with fuel efficiency and emissions requirements and commence domestic manufacturing of advanced technology vehicles;

- achieve a positive net present value, using reasonable assumptions and taking into account all existing and projected future costs, including repayment of the Loan Amount and any other financing extended by the Government;

- rationalize costs, capitalization, and capacity with respect to the manufacturing workforce, suppliers and dealerships; and

- have a product mix and cost structure that is competitive in the U.S.

The Bush-era loans also set non-binding targets for the companies. There was no penalty if the companies developing plans missed these targets, but if they did, they had to explain why they thought they could nevertheless still be viable. We took the targets from Senator Corker’s floor amendment earlier in the month:

- reduce your outstanding unsecured public debt by at least 2/3 through conversion into equity;

- reduce total compensation paid to U.S. workers so that by 12/31/09 the average per hour per person amount is competitive with workers in the transplant factories;

- eliminate the jobs bank;

- develop work rules that are competitive with the transplants by 12/31/09; and

- convert at least half of GM’s obliged payments to the VEBA to equity.

If, by March 31, the firm did not have a viability plan approved by President Obama’s designee, then the loan would be automatically called. Presumably the firm would then run out of cash within a few weeks and would enter a Chapter 7 liquidation process. We gave the President’s designee the authority to extend this process for 30 days.

The Bush-era loans were not a blank check, not a “straightforward bailout.” President Obama was wrong when he said they were.

(photo credit: paul bica)

President Obama’s decision to waste (at least) $60 B

Yesterday The New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza published an analysis of President Obama’s first two years of decision-making on economic policy. Mr. Lizza also released a 57 page memo sent to President-elect Obama by Dr. Larry Summers (later NEC Director) on December 15, 2008. Mr. Lizza reports that the memo contained input from Dr. Christina Romer (later CEA chair) and Dr. Peter Orszag (later OMB Director).

Together the memo and article provide insight into the formerly private thinking of President Obama and his advisors. Their approach to fiscal policy is quite different from my own, most especially the confidence they express in their estimates of the effectiveness of government spending to accelerate economic growth.

Even more interesting is that given this approach to economic policy, the memo and story describe a President who chose to ignore his policy advisors and to waste tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer money so he could have an inspiring talking point and help his partisan Congressional allies get their pork. That’s disturbing even if you accept the pro-stimulus approach to fiscal policy.

Three quotes in the Summers memo describe a tension in the design of the stimulus proposal. Here is the first (p. 7):

<

blockquote>Constructing a package of this size

Here is the second (p. 12):

Peter Orszag and OMB career staff, together with NEC staff, have worked with the policy teams to identify as much spending and targeted tax cuts as could be undertaken effectively in six priority areas: energy, infrastructure, health, education, protecting the vulnerable, and other critical priorities. The short-run economic imperative was to identify as many campaign promises or high priority items that would spend out quickly and be inherently temporary. The long-run economic imperative, which coincides with the message imperative, is to identify items that would be transformative, making a lasting contribution to the American economy.

Here is the third (p. 12, emphasis in the original):

[I]t is important to recognize that we can only generate about $225 billion of actual spending on priority investments over next two years, and this is after making what some might argue are optimistic assumptions about the scale of investments in areas like Health IT that are feasible over this period.

I’ll interpret:

- The advisors selected their core spending priorities by “identify[ing] as many campaign promises or high priority items that would spend out quickly and be inherently temporary.” They started their spending decision process by fulfilling campaign promises.

- They could identify $225 B of spending they thought met their criteria. Even that number included optimistic assumptions on how much they could spend quickly for Health IT and other areas.

- From a macro standpoint they felt they needed a bigger aggregate number, so they moved to lower priority items. The President chose a (hoped for) big macro effect over a smaller bill that used taxpayer money more efficiently.

Mr. Lizza then describes the President pushing back on his economic advisors:

At a meeting in Chicago on December 16th to discuss the memo, Obama did not push for a stimulus larger than what Summers recommended. Instead, he pressed his advisers to include an inspiring “moon shot” initiative, such as building a national “smart grid”—a high-voltage transmission system sometimes known as the “electricity superhighway,” which would make America’s power supply much more efficient and reliable. Obama, still thinking that he could be a director of change, was looking for something bold and iconic—his version of the Hoover Dam—but Romer and others finally had a “frank” conversation with him, explaining that big initiatives for the stimulus were not feasible. They would cost too much, and not do enough good in the short term. The most effective ideas were less sexy, such as sending hundreds of millions of dollars to the dozens of states that were struggling with budget crises of their own.

Mr. Lizza suggests the President cared more about messaging and “inspiring ‘moon shot’” spending while his advisors focused on strengthening the economy. Note that Mr. Lizza’s description of Dr. Romer’s advice on the effectiveness of aid to states contradicts the Summers memo.

Mr. Lizza then reports that on February 1, 2009, the President’s advisors asked him to tell Democratic Congressional leaders that the package must not exceed $900 B. Here’s more from Mr. Lizza:

Senators would likely amend the bill to add about forty billion dollars in personal projects—some worthy, some wasteful. At the same time, Obama hadn’t abandoned his dream of a moon-shot project. He had replaced the smart grid with a request for twenty billion dollars in funding for high-speed trains. But including that request was risky. “Critics may argue that such a proposal is not appropriate for a recovery bill because the funding we are proposing is likely to be spent over 10+ years,” the advisers wrote.

To find the extra money—forty billion to satisfy the senators and twenty billion for Obama—the President needed to cut sixty billion dollars from the bill. He was given two options: he could demand that Congress remove a seventy-billion-dollar tax provision that was worthless as a stimulus but was important to the House leadership, or he could cut sixty billion dollars of highly stimulative spending. He decided on the latter.

If Mr. Lizza’s reporting is correct, over the objection of his economic advisors President Obama replaced $60 B of “highly stimulative spending” with a slow-spending but “inspiring” $20 B for high-speed trains and $40 B in pork for his Senate Democratic allies. And this is starting from a point at which he knew that his advisors thought that not more than $225 B of the $826 B total was high-quality, fast-spending, efficient stimulus.

p.s. This post shows why you don’t release to the public memos written to the President by his senior advisors. Presidential advisors are supposed to protect the advice they give to the President. The decision to give Mr. Lizza access to so many confidential memos to the President was either blindingly stupid or shockingly disloyal, and it damaged the institution of the Presidency.

(photo credit: Trey Ratcliff)

President Obama’s changing economic problem definition & deficit strategy

In advance of tomorrow’s State of the Union address I have been rereading President Obama’s major economic speeches. I had hoped to show a progression of argument, but that didn’t pan out. Instead two things jumped out at me: the President’s primary economic problem definition has varied widely over time, and his deficit message has changed even more. I will attempt to summarize each in chronological order.

Here is how President Obama has defined America’s primary economic problem and his policy response. In each case the language is my paraphrase of the President’s message.

- [2009-10] I inherited a mess – an economy in freefall. My actions prevented a depression.

- [early 2009] We had a bubble-and-bust economy. I am moving the economy from one built on financial bubbles to one built on a “new foundation” of financial reform, education, renewable energy, health care, and deficit reduction.

- [2009-10] Health care costs hurt families, businesses and the federal budget. My bill will slow health cost growth and solve the deficit problem while insuring everyone.

- [spring 2010-present] For decades the middle class has been squeezed, owing more and making less. My new foundation and tax increases on the rich will fix that.

- [fall 2010] The rich don’t pay enough in taxes. Let’s raise their taxes.

- [early 2011] International competition: China and India have better new infrastructure than we do. Let’s spend money on infrastructure, education, health care, and green jobs.

- [summer 2011] I want to fix the long-term deficit.

- [fall 2011-present] Income inequality is a huge problem and has been for decades. The rich are sticking it to the middle class. I’m for the middle class, so let’s raise taxes on the rich.

While the above list spans a fairly wide range, the arguments are at least roughly consistent with one another. In contrast the President’s policy and message on the deficit has ranged all over the map.

- [2009] We need to fix the economy first. Worry about the deficit later.

- [2009-10] Health care reform is the answer to long-term deficit problems.

- [early 2010] I’m appointing a fiscal commission to solve the long-term deficit problems.

- [early 2011] [I’m ignoring the fiscal commission and don’t really have a deficit message and] I have other priorities to spend on infrastructure, education, health care, and green jobs.

- [spring 2011] I’m matching Republicans on deficits [not really] with a new budget proposal [or speech].

- [summer 2011] I want a grand bargain on the long-term deficit. I’m the centrist adult trying to work with Speaker Boehner but those crazy Tea Party Republicans won’t cooperate.

- [fall 2011 – present] I want to raise taxes on the rich.

Tuesday night I’ll be watching to see if the President sticks with his most recent economic problem definition and how he now proposes to address America’s fiscal imbalance.

(photo credit: Drew Bennett)

Fannie & Freddie in the payroll tax cut bill

The payroll tax cut bill that will soon become law takes a small step in the right direction on policy toward the Government-Sponsored Enterprises, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Congratulations to Congress for this small step; they still have a long way to go.

What the bill does

When Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac guarantee and securitize a bundle of mortgages they charge a guarantee fee or G fee for the service. The bill mandates an increase of 10 basis points (one-tenth of one percentage point) in this guarantee fee.

Since this is a fee charged by Fannie and Freddie to their clients, by itself this provision would increase revenue for the firms. The bill also requires Fannie and Freddie to passthrough that increased revenue to the U.S. Treasury. This would increase federal government revenues and reduce the budget deficit. That’s why the provision is in this bill, because Democrats are insisting that the deficit effects of preventing a tax increase be offset with provisions that reduce the deficit.

These additional 10 basis points of guarantee fee, passed through to the U.S. Treasury, would result in about $3.5 B extra revenue and deficit reduction per year for the federal government over the next decade.

My long run policy goal

I believe the Government Sponsored Enterprises should be replaced with a private market for mortgage securitization.

While in theory one could privatize Fannie and Freddie and sever all their ties to the federal government, as was done with Sallie Mae (student loans) in the late 90s, I fear, because of both the history of housing GSEs and the temptations such an effort would present to policymakers, that the result would be a continuation of the failed hybrid government-private model that has caused so many problems. Even as fully private firms, financial regulators would deem them to be too big to fail and implicitly guarantee them. I am therefore not for reforming the GSEs, but replacing them with a private market.

Increasing the guarantee fee is a step in the right direction

Long before 2008 the government bestowed many policy and legal advantages to Fannie and Freddie, creating an implicit government guarantee for the firms. As a result lenders were willing to loan funds to these firms at a lower interest rate than to their private sector counterparts.

The 2008 crisis turned that implicit guarantee explicit. Fannie and Freddie continue to operate with a borrowing advantage. This is a principal cause of their continued overwhelming dominance of the mortgage securitization market.

Increasing the guarantee fee reduces that borrowing advantage and weakens this government-created oligopoly. A 10 bps increase is a small step in the right direction, no matter what is done with the increased revenues.

What should be done with the increased fees?

Some investors are telling Congress that the higher fees should be left in control of Fannie and Freddie’s management rather than passed through to pay down the deficit. These increased guarantee fees should not, they argue, be “used to pay for a payroll tax cut,” and they argue that doing so undermines the prospect of future GSE reform.

The “pay for a payroll tax cut” argument is a red herring being used with Republicans who don’t like the payroll tax cut policy. Imagine if instead this were a standalone bill consisting only of the higher guarantee fee. Should those funds be used by the government for deficit reduction or left with Fannie and Freddie executives, to be used at their discretion for some other purpose?

What is a higher use of these increased revenues than to reduce the federal budget deficit?

- Is further subsidizing other mortgages, maybe under one of the Administration’s multiple failed housing initiatives, better than reducing the deficit?

- Is paying back private investors who own GSE debt, were bailed out by tens of billions of dollars of taxpayer funds, and are now lobbying Congress, better than reducing the deficit?

- Is allowing Fannie and Freddie executives, the top six of whom were paid $35.4 M in 2009 and 2010 (about half to the two CEOs), flexibility to pay themselves more better than reducing the deficit?

I think these funds should be used to reduce the deficit. Packaging this deficit reduction with deficit-increasing policies that I don’t prefer (like the payroll tax cut) does not change this judgment.

Some of these investors now lobbying Congress to leave the higher revenues with the GSEs are holders of GSE debt who have apparently forgotten that taxpayers spent tens of billions of dollars to bail them out.

Does increasing the guarantee fee now undercut future replacement or reform of the GSEs?

I have heard an argument that raising the guarantee fee now will undermine future efforts to replace or reform of the GSEs. By “using” this deficit reduction to pay for something else now, the higher government revenues will not be available in future legislation, making that legislation harder to enact.

This argument is qualitatively correct but quantitatively insignificant. The GSEs’ borrowing advantage is far more than 10 basis points, so there is a lot more revenue that could be raised even to get to a level playing field. Don’t forget that these fees are only one side of the ledger. Since 2008 Fannie and Freddie have had an unlimited tap on taxpayer funds to continue functioning. These past and present subsidies exceed the proposed increase in guarantee fees. Replacing the GSEs with a fully private market, or even simply eliminating their explicit and implicit taxpayer subsidies, would still be a big deficit reducer and would therefore make future legislation quite attractive from a deficit hawk viewpoint.

The higher mandated guarantee fee and the required passthrough to reduce the deficit are good policies and small steps in the right direction.

(photo credit: futureatlas.com)

Addendum: I see that Peter Wallison has a different view on whether the higher fees undercut future efforts at reform. I’d like to make three points in response.

- Most importantly, I would never group Peter with the self-interested investors I describe above. While many of those arguing against raising the guarantee fee and passing the revenue through to Treasury are, I think, investors and expanded government housing advocates masquerading as free market conservatives, Peter most definitely is not. He has a longstanding record as a proponent for the strongest of GSE reforms.

- As described above, I’m not worried about the “piggy bank” point, because the dollar figures are small and there are outlays on the other side. Even if it is a slight deterrent, I’m willing to accept that for the benefits of reducing slightly the funding advantage the GSEs have.

- Peter describes other hurdles to a fully private mortgage securitization market. I need to study these further. Assuming Peter has them right, I don’t see them conflicting with my view that raising the guarantee fee is a good thing. It means instead that raising the g fee is necessary but may not be sufficient to getting to a completely private market.

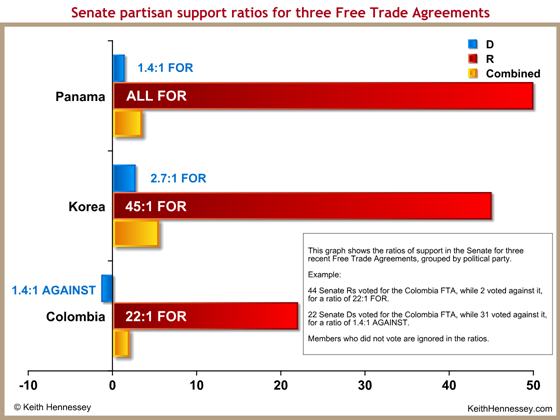

Free trade voting patterns in Congress

I find I can learn a lot by graphically examining legislative voting patterns. The recent enactment of implementing legislation for three Free Trade Agreements gives us a wonderful opportunity to compare the two political parties and the House and Senate on free trade.

Background

The Bush Administration negotiated free trade agreements (FTAs) with Korea, Colombia, and Panama. South Korea’s economy is big enough that the Korea FTA was economically important not just for South Korea, but also for the U.S. FTAs with smaller Colombia and Panama are important to the U.S. for several non-economic reasons:

- These countries are our friends and allies (so is South Korea).

- There is a long run philosophical battle for the shape of Central America, with Venezuela’s Chavez and Cuba’s Castro brothers on the other side. Helping Central American countries that want to expand freedom, democracy, capitalism, and free trade helps our side in that broader struggle.

- It is important for the U.S. to send a signal to smaller nations of the world that we will pursue free trade with countries whose economies are quite small relative to ours.

- We also want to promote the idea of free trade generally.

Upon taking office President Obama said all three FTAs were flawed and sent his trade representative to renegotiate each one. Even after renegotiations concluded in late 2010, the President sat on them for many months. He sent implementing legislation for all three agreements to Congress in October of this year. All three were ratified by Congress in less than three weeks.

The two years of renegotiations were politically convenient for President Obama, as they allowed him to avoid asking Speaker Pelosi to bring up legislation that most of her caucus opposed. The following vote analysis will show this.

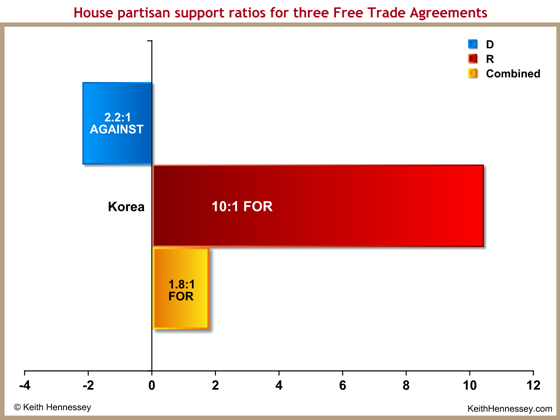

Partisan support ratios

Since I want to focus principally on comparing the two parties, I think that looking at partisan support ratios for the FTAs.

Example:

- 219 House Republicans voted for the Korea FTA, while 21 voted against it, for a ratio of 10:1 House Rs FOR.

- 66 House Democrats voted for the Korea FTA, while 123 voted against it, for a ratio of 2.2:1 House Ds AGAINST.

- As a whole, 278 House Members vote for the Korea FTA, while 151 voted against it, for a ratio of 1.8:1 House Members FOR.

I found that looking at raw vote counts gets klunky. Look at how much easier it is when we compare ratios and have an apples-to-apples comparison of different groupings:

|

House |

House Rs |

House Ds |

|

1.8:1 FOR |

10:1 FOR |

2.2:1 AGAINST |

Even better, we can look at it as a graph:

This means that for every 1 House Republican who voted against the Korea FTA, 10 of them voted for it. In contrast, for every 1 House Democrat who voted for the Korea FTA, 2.2 of them voted against it.

Obviously, an FTA would pass the House only if its total support ratio (Rs+Ds) is greater than 1:1.

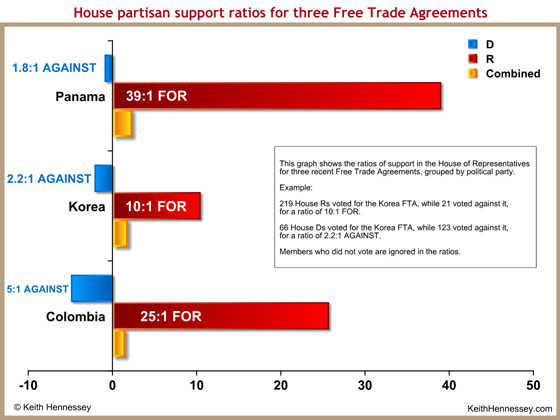

Now this voting pattern is not unusual for the House on any legislation. As a majoritarian body, the House is naturally partisan. Bills usually pass the House relying mostly if not entirely on the majority party’s votes. We can see that this is the case for all three FTAs in October:

We can learn a few things from this graph:

- In each case, House Republicans voted overwhelmingly in favor of the FTA. The lowest ratio was for Korea, and that was still 10:1 FOR.

- In each case a majority of House Democrats voted against the FTA (that’s why the ratios are measured as AGAINST). But also in each case, the Democratic party split more deeply than Republicans (since the ratios are closer than 1:1).

- As a working hypothesis from looking at these House votes, we can conclude that House Democrats are generally against free trade, but House Democrats are less unified as a party than the pro-free trade House Republicans.

- We also have a plausible explanation for why President Obama took so long. All three FTAs split his party deeply with most of his partisan allies opposed. By taking two years to renegotiate the FTAs, he did not have to put his House allies in an uncomfortable position while he was relying on them to enact the stimulus, health care, and Dodd/Frank.

Now let’s test these hypotheses by looking at the corresponding Senate votes:

This is more interesting than the House vote. Remember that Democrats are still in the majority in the Senate.

- In all three cases Senate Republicans voted even more overwhelmingly for free trade than did House Republicans. But for the Maine Republican Senators Snowe (2 nos) and Collins (1 no), Senate Republican support for all three FTAs was unanimous.

- Unlike House Democrats, a majority of Senate Democrats voted for the Panama and Korea FTAs. More Senate Ds voted no on Colombia than voted aye, but the ratio (1.4:1 AGAINST) was much closer than among House Ds (5:1 AGAINST).

- Almost all Senate Republicans and a majority of Senate Democrats supported Panama and Korea, while the Colombia FTA leaned more heavily for passage on Republican votes.

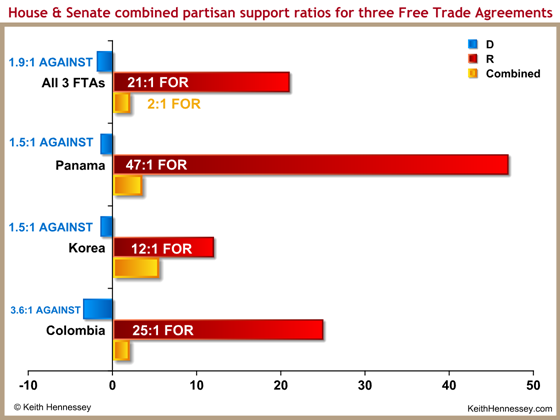

I also did some aggregate tabulations, combining the votes of all three FTAs together. This is useful for comparing the political parties in the aggregate. It also gives more weight to the House than the Senate, since there are more House members than Senators.

These results won’t surprise anyone who has followed trade policy and politics in the U.S.

- The Congress (House + Senate combined) voted 2:1 FOR the three trade agreements.

- Republicans voted 21:1 FOR free trade.

- Democrats voted 1.9:1 AGAINST free trade.

Can we extend the results from these three FTAs to a broader analysis of the two parties on free trade? Yes and no.

- The renegotiation and a Democrat in the White House provided more political cover for on-the-fence Democrats to vote aye. That would suggest these ratios are a free trade high water mark for the Democratic party.

- Partly offsetting this, many of the House Democrats who lost their seats in the 2010 tidal wave election were in more centrist/purple districts and may have been more free trade than those who survived the wave. I think this factor is small relative to the first, however.

- The above ratios are even more free trade than I expected from Republicans. Protectionist Republicans tend to be from the South (textiles), and none of these FTAs economically threatened the American South. I would generally guess between an 8:1 and a 12:1 FOR ratio for Congressional Republicans rather than the 21:1 that we saw in October.

Free trade in the U.S. results from a center-right legislative alliance.

- In my experience the above analysis reflects a broad historic trend, at least over the past 15 years or so. See the free trade vote here for a comparison.

- In the U.S. free trade agreements pass the Congress with a broad center-right legislative alliance that includes almost all Republicans and splits Democrats roughly one-third for free trade and two-thirds against it.

- When looking at all three FTAs combined, House Democrats voted 2.6:1 AGAINST free trade in October, even with a Democratic President supporting the FTAs. You need a House Republican majority to get any free trade done. There’s no way a Democratic Speaker can bring free trade legislation to the floor when her own party is so heavily opposed to it.

Three layers of the European debt crisis

This post is for Americans who know nothing about the debt crisis in Europe. I am going to try to provide a big picture framework and draw attention to what I think should matter most to Americans. If you have expertise in this topic I hope you’ll help me improve my analysis. This topic is somewhat new for me.

I think of the European debt crisis in three layers:

- national debt crises in several European countries;

- a structural crisis of the Eurozone; and

- potential banking crises in Europe and the U.S.

Most current press coverage is about the middle layer: can European leaders prevent the Eurozone from dissolving? The top and bottom layers deserve more attention than they are receiving. American policymakers need to think hard about and plan for the possibility that a really bad outcome in Europe leads to another American banking crisis.

On the top layer we have national budget crises in several countries. For weeks and in some case months, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain (the so-called PIIGS) have each had trouble issuing government bonds at a sustainably affordable interest rate. Each of the PIIGS has some combination of unsustainably high budget deficits, high government debt, and weak economic growth. As a result investors worry that if they loan money to these governments they won’t get it back in full and on time. They therefore insist on a high interest rate to compensate for this risk. In the case of Greece those fears were well-founded, as private investors “voluntarily” (yeah right) took about a 50% haircut on the value of their Greek bonds.

On this top layer of national debt crises there are a few important things to remember:

- Each of the PIIGS’ fiscal situations is different. Spain had a housing bubble like we did in the United States. Ireland incurred a lot of debt because they bailed out their banks in 2008 and 2009. The Italians have a lot of debt while the Greeks have huge deficits. Each of these countries is having trouble issuing government (“sovereign”) debt at an affordable interest rate, but for different reasons.

- A growing economy can cover up a lot of problems. An economic slowdown in Europe has revealed problems in the PIIGS that have been building, in some cases for years.

- At this fiscal solvency layer the idea of “contagion” from one of the PIIGS to another is overblown. The underlying fiscal solvency crises in these governments are basically independent. While the reactions of policymakers to Greece is affecting investors’ expectations about the value of debt issued by Italy, Spain, or Portugal, the underlying fiscal solvency problems in these countries were not caused by the problems in Greece. Contagion pops up in other parts of this story, but the term is often misused in this layer. See this Lazear op-ed for more on this point.

- From a broad American perspective we care about each of these countries because we want our friends and allies to succeed economically. From a narrow American economic self-interest viewpoint, we care about each because they are our trading partners. But on the raw numbers the economic fate of each of them (separately) will have only a small effect on the U.S. economy. If we in the U.S. did not have to worry about the other two layers, then this would probably not be the most important current issue for most American economic policymakers. The worrisome quantitative hit to the U.S. economy comes if Europe as a whole goes into a deep recession, or if European debt problems cause a banking crisis that spreads to the U.S.

In the middle layer we see the Europeans trying to solve the structural flaw of having a centralized monetary policy in a Eurozone economy that is still heavily balkanized, especially on fiscal policy. Because my point today is to emphasize the relative importance of the other two layers relative to this one which is getting all the public attention, today I’ll mention only a few important points about this layer.

- Outside of a monetary union, a government that borrows in its own currency and develops debt problems has the option of inflating away its liabilities. This generally also occurs in the context of a currency devaluation. The PIIGS don’t have this option as long as they are members of the Eurozone, since they don’t control their own monetary policy, inflation, or currency. This means they must either make dramatic changes to solve their underlying fiscal problems (which, presumably is quite difficult given that they haven’t done it so far) or they have to get someone else to help them pay their bills. (translation: “someone else” = Germany)

- In theory Greece or Portugal could leave the Eurozone, reinstitute their own currency, and then devalue. In practice ut the treaties that formed the Eurozone don’t describe how to do this, and you have to worry about capital flight, how to get anyone to use your new currency, and how to deal with old contracts and debts denominated in Euros when you’re now using drachmas or lira. I have yet to find someone who can describe how a country could successfully do this, legally or financially.

- Given this huge uncertainty about whether and how a country could actually leave the Eurozone, there appear to be a few possible outcomes:

- Everyone now in the Eurozone stays in it;

- Some of the smaller periphery countries (Greece, Portugal? Ireland?) leave it (but how?), while the rest in the core stays intact; or

- The whole Eurozone falls apart.

- If the whole Eurozone falls apart, then Europe as a whole probably falls into a deep recession. That would seriously hurt the rest of the world’s economies, including ours. This is a bad scenario for a U.S. economy that is already growing way too slowly. It’s also a scenario that American policymakers can do little to prevent. Chancellor Merkel and President Sarkozy are doing everything in their power to avoid this outcome.

The bottom layer, the interaction between European sovereign governments and banks in Europe and the U.S., is not getting nearly enough policy or press attention, and it worries me a lot. From an American self-interest perspective, the direct economic effects of a Eurozone collapse on U.S. exports would be very bad and could easily tip the U.S. into recession. But the effects of a collapsed Eurozone or an Italian default on European banks, and the indirect effects that are passed through to American banks, could be far, far, worse. Think 2008 financial crisis worse. The worst case scenarios for Europe appear to pose a low probability, high consequence threat of another horrific U.S. banking crisis. This is why American policymakers should care deeply about Europe — because if the Europeans screw it up badly, it could do serious damage to the American economy, transmitted through still flawed and vulnerable banking systems.

A sudden dip in the value of Italian debt could create solvency problems and/or liquidity problems for banks and other large financial institutions. Here is the solvency scenario that really scares me:

- Italy defaults on its sovereign debt or the Eurozone collapses. Italian debt is suddenly worth much less.

- Everyone holding Italian bonds, or derivative securities based on Italian bonds, suddenly must realize a big loss.

- Large European banks that were holding massive quantities of Italian debt must realize huge losses. The biggest concern here is probably the big French banks, but there could be others throughout Europe that face similar risks.

- These European banks fail. European governments begin rescuing their banking systems (again).

- While large American banks appear to face little direct exposure to the risk of losses on Italian bonds, they could face much larger counterparty exposure to failing large European banks that hold those Italian bonds.

- Failures of European banks trigger large losses in large American banks.

- Some of the biggest American banks fail. Again.

To put it even more simply, I worry about this:

(Eurozone collapses or Italian government defaults) –> European banks fail –> U.S. banks fail

A second and closely related scenario derives from European banks using PIIGS government bonds as collateral for short-term interbank loans. If a European bank needs an overnight loan from another bank, and that second bank won’t take Italian government bonds as collateral, then the first bank may need to sell other assets to raise cash. If a whole class of collateral for liquidity is no longer available, it can have broader effects in liquidity markets, including for U.S. banks that don’t use European sovereign debt as collateral but rely on these wholesale markets for short-term liquidity. This could force the U.S. Fed to once again provide emergency liquidity to American banks.

From a narrow American economic self-interest standpoint, our second biggest concern should be whether our trading partners go into a deep recession and what that would mean for U.S. exports and U.S. GDP growth. Our biggest concern should be the value of Italian bonds. Why? Because there are a whole lot of them, and because they are concentrated in large European banks that (as best I can tell) are counterparties to large American banks.

You may notice parallels to 2008. Then, big American banks failed in part because they concentrated huge amounts of highly correlated mortgage risk on their balance sheets. When those housing-related financial assets declined sharply in value, those banks failed. The same could happen in Europe, where government debt has previously been (mistakenly and stupidly) treated as a risk-free financial asset. We Americans should care specifically about Italian debt because there is so much of it, because it is concentrated on the balance sheets of some large European financial institutions, and because these institutions are now realizing it’s risky and worth less than they had previously thought.

An even better 2008-era analogy would be debt issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. U.S. rules allowed banks and other financial institutions to treat this Agency debt as risk free and as functionally equivalent to U.S. Government bonds. As a result, financial institutions around the world concentrated huge amounts of apparently risk free Agency debt on their balance sheets. When in 2008 Fannie and Freddie were deemed to be insolvent, we in the Bush Administration worked with the regulator to in effect guarantee that Agency debt would be worth 100 cents on the dollar. We did this because the alternative would have triggered failures in financial institutions around the world. The U.S. financial system mistakenly treated Agency debt as risk free. When that was no longer true because the underlying institutions were recognized to be insolvent, we had to step in to make it risk free or else, we thought, face the collapse of much of the global financial system. European sovereign debt, and especially Italian bonds, appear to be the 2011 equivalent, at least in Europe, of 2008 era Agency debt.

Over the past week there have been significant policy actions on all three layers of the crisis:

- New Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti has proposed and is trying to enact new laws to address his government’s underlying solvency problems;

- European leaders and finance ministers are working furiously to figure out how to hold the Eurozone together; and

- The U.S. Federal Reserve started a new stress test of big American banks to figure out whether they could withstand an economic shockwave from a European implosion.

While the press focuses almost entirely on the Eurozone negotiations, American policymakers should be focusing even more on whether PM Monti is successful in Italy and especially on the results of the U.S. Fed’s stress tests.

Unlike with U.S. mortgages in 2008 and thereafter, the Italian government can solve its underlying solvency problems. Through some combination of cutting government spending, raising taxes, and economic reforms that will allow more economic flexibility and competition and faster productivity growth, the Italian government can reduce the risk of insolvency and increase the value of Italian debt. This would help Italy, it would make it easier to keep Europe intact, and it would reduce the risk to the European and banking systems. Win-win-win.

At the same time the U.S. Fed is requiring the biggest banks to test a scenario in which U.S. GDP declines eight percent and the unemployment rate jumps to 13%. I hope they are also requiring the American banks to prove they can survive if their European counterparts fail or if liquidity suddenly dries up. These stress tests, and corrective actions demanded of any American banks that fail the tests, are the most important thing American policymakers can do now to protect the American economy from the worst case scenarios in Europe.

From an American economic self-interest perspective, this bottom layer of the European debt crisis is by far the most important. If events in Europe could cause American banks to fail, American policymakers need to know this and deal with it before disaster strikes.

(Hat tip to the students in my Stanford Business School class who have been helping me learn and think about the European crisis and how to explain it.)

(photo credit: FurLined)