President Obama made two strategic mistakes last Friday

President Obama made not one but two strategic mistakes last Friday. Everyone paying attention picked up on his first mistake. The President said “The private sector is doing fine,” a quote that Republicans will use to great effect during the remainder of this election cycle.

The President’s second mistake is as important but less obvious. President Obama spoke a second time Friday afternoon. He did not, as reported by some, correct his earlier statement. He instead reinforced it. The President’s second mistake was his decision to stick with an economic argument that is unsupportable by facts, easy to disprove, and politically damaging to him. President Obama will never again say “The private sector is doing fine,” but it appears he will continue to make an economic argument that Republicans can easily rebut.

In addition to the specific deadly quote, this second Presidential mistake presents a significant election opportunity for Governor Romney and other in-cycle Republicans, but only if they treat the President’s argument as serious and seek to debate him, not just to hurl invective. The President is sticking to his guns about what ails the economy and how to fix it. Republicans should relish the opportunity to debate this question extensively.

President Obama’s argument has two components.

- Diagnosis: Employment weakness is principally a problem of too few government jobs.

- Prescription: Despite record high deficits and debt and while private sector unemployment is high, the federal government should give States and localities money to protect the jobs of existing government workers and hire new ones.

President Obama’s diagnostic error

The President’s diagnosis is incorrect. The principal drag on U.S. economic growth is high unemployment, but the bulk of that unemployment is among people who previously had private sector jobs. The President is correct that private sector employment has been growing slowly over the past 2 1/4 years, while government employment has been shrinking slowly. And yet laid off government workers are still a small fraction of the unemployment problem.

I covered this in detail in yesterday’s post. For today here is the key statistic:

For every net lost government job since employment peaked in January 2008, the U.S. economy has lost more than eleven private sector jobs.

President Obama’s prescriptive error

Since his diagnosis is wrong it’s not surprising that the President’s policy prescription is misguided. Yes, police officers, firefighters, and teachers are valuable members of their communities. One can like these kinds of public servants and still think the President’s policy is a bad idea.

First, the loss of government jobs over the past few years is almost entirely a local phenomenon. Outside of a steadily shrinking Postal Service, there are 142,000 more federal government employees today than when the President took office.

Police, firefighters, and teachers are all local government employees, traditionally funded by localities from local revenue sources. Localities vary widely. They have different needs, their tax and spending priorities differ, and they express different degrees of fiscal responsibility. Federalizing this local spending forces taxpayers in one area to subsidize high cost, inefficient, or fiscally irresponsible local governments in another.

Second, it’s not like the federal government has money to spare. Federal budget deficits and debt are at record highs. Even if Congress were to pay for increased grants to localities, the spending cuts and/or tax increases used to offset this spending would then be unavailable for other federal priorities.

Third, the President is arguing that government job growth is the engine of the U.S. economy. Here is the President last Friday:

The folks who are hurting, where we have problems and where we can do even better, is small businesses that are having a tough time getting financing; we’ve seen teachers and police officers and firefighters who’ve been laid off — all of which, by the way, when they get laid off spend less money buying goods and going to restaurants and contributing to additional economic growth.

The President’s prescription is to spend more federal taxpayer dollars (that government must borrow) to subsidize localities hiring more government workers, in the hopes that those government workers will then spend their income in ways that will help private sector growth.

The President is wrong. The private sector, not expanded government payrolls, is the path to faster economic growth. Policies should prioritize creating conditions under which private firms choose to expand and hire. This relates closely to recent debates in Wisconsin, New Jersey, and other States.

Fourth, even if you think increased local government hiring is a good idea, temporary federal subsidies don’t create long-term government jobs. Three years ago the President and a Democratic Congress juiced local budgets with the stimulus bill. Now that those funds have run out, they are seeking to do so again. If Congress says yes they’ll be back again and again each time those funds will run out. Temporary subsidies will become permanent.

Fifth and finally, the President argues that government employment should not decrease when the economy is weak. He contradicts what I call the Christie Principle of Shared Sacrifice. This is my wording but the Governor’s concept:

At all times, and especially during a difficult economy, it is unfair to exempt government and government workers from the difficult financial decisions that privately employed and unemployed citizens must make. Sacrifice should be shared and include government cutbacks.

The Republican response

Republican responses to the President’s Friday comments have been aggressive and clumsy. Some have attacked the President for arguing that the economy is doing fine, but he did not say that. Others have attacked him for saying that he prefers government jobs to private sector jobs, or at least sees them as morally equivalent. He might, but again he didn’t say that either. Still others link “The private sector is doing fine” to an assortment of economic woes, including indirectly related problems like high budget deficits and debt.

These are poorly targeted responses to the President’s first mistake last Friday, the devastating quote that we know he will never repeat. Republicans would be more effective if they rebutted his specific claim, that the private sector, and specifically private sector employment, is doing fine.

The President’s second strategic mistake presents an additional and ongoing opportunity that Republicans should not miss. Policymakers and candidates should seek to debate the President’s intellectual premise, to engage him in a serious public discussion about both his diagnosis and his prescription.

Doing so requires hard work of the kind involved in battling the health care and stimulus laws. This hard work will pay off. The President’s intellectual premise is so weak that Republicans can win this debate with both elites and voters, but only if they treat it as a serious policy matter and not just a sound bite. Engaging in and winning this debate will advance good policy and increase Republicans’ chances of victory on Election Day.

(photo credit: White House video)

Is private sector employment fine in absolute or relative terms?

President Obama’s argument last Friday that “the private sector is doing fine” caused quite a flap. He made two arguments:

- Private sector employment is doing fine in absolute terms.

- Private sector employment is doing fine relative to government employment.

His opening remarks emphasize absolute job growth in the private sector. Note “our businesses have created” in the following quote.

THE PRESIDENT: After losing jobs for 25 months in a row, our businesses have now created jobs for 27 months in a row — 4.3 million new jobs in all. The fact is job growth in this recovery has been stronger than in the one following the last recession a decade ago. But the hole we have to fill is much deeper and the global aftershocks are much greater. That’s why we’ve got to keep on pressing with actions that further strengthen the economy.

As you would expect from any President he is highlighting the positive: both the change in level (+4.3 M jobs) and the trend line (created net jobs for 27 months in a row). These are prepared remarks, so we know he intended to make these points.

Here is the second quote, the one that is causing controversy.

THE PRESIDENT: The truth of the matter is that, as I said, we’ve created 4.3 million jobs over the last 27 months, over 800,000 just this year alone. The private sector is doing fine. Where we’re seeing weaknesses in our economy have to do with state and local government — oftentimes, cuts initiated by governors or mayors who are not getting the kind of help that they have in the past from the federal government and who don’t have the same kind of flexibility as the federal government in dealing with fewer revenues coming in.

And so, if Republicans want to be helpful, if they really want to move forward and put people back to work, what they should be thinking about is, how do we help state and local governments and how do we help the construction industry.

In a future post or two I’ll look at the why behind the President’s logic. In this post I just want to focus on the what, the basic facts of the case.

Let’s take the President’s claim seriously. What would lead him to claim that (1) the private sector is doing fine, and (2) the problem is in government employment rather than private employment, thus necessitating his policies of increased federal spending to create more government jobs?

I think you will see that there are facts that support the President’s arguments, but only if you choose one particular timeframe.

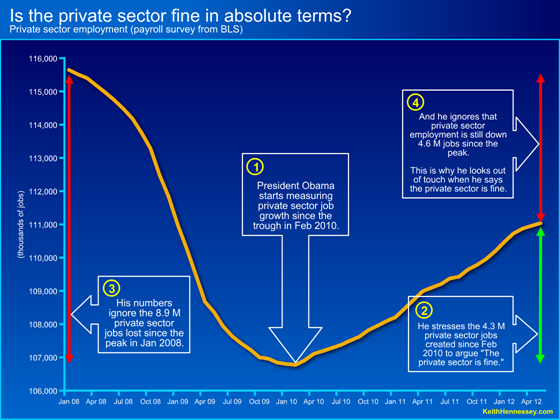

First let’s look at the claim that private sector employment is fine in an absolute sense. Rather than making my argument in text surrounding the graph, my core arguments are on the following three graphs, so please study them carefully. You can click on any graph to see a larger version.

President Obama is focusing on changes since employment bottomed in February 2010 – we know that from his “past 27 months language,” as well as his measure of the change since then (+4.3 M private sector job). I’m calling February 2010 the employment trough.

There is nothing wrong with focusing on the positive, and it’s to be expected when you’re running for office. If, however, it leads you or those listening to you to incorrect policy conclusions, then it can be quite dangerous.

Which number is the right way to think about private sector employment? Is it the +4.3 M jobs created since February 2010? Is it the 4.6 M fewer jobs that exist then when we were at peak employment in January 2008? The right answer is “both and neither.” There is no single right way to think about the change in employment. It is important that we see as full a picture as possible, and the President is showing us only part of the picture, the upward sloping portion of the above graph.

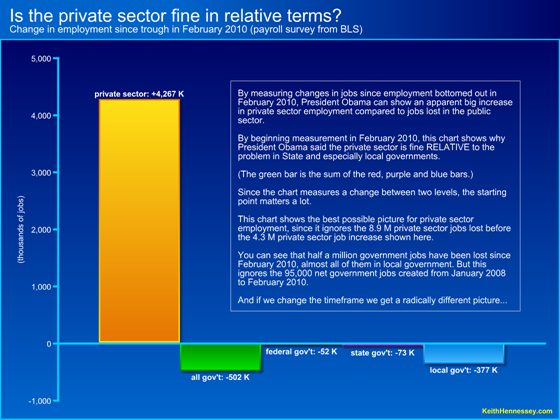

Now let’s examine the change in private sector employment relative to the change in government employment. We will study it over two time frames: first using the President’s framework of changes since the trough in February 2010, and second using my framework of changes since the employment peak in January 2008. Here is a graph that supports the President’s controversial quote.

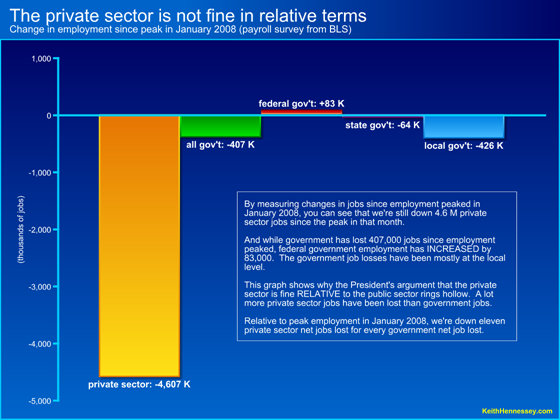

The above chart makes the President’s case, but it tells only part of the story, just as you only get part of the story if you begin the first graph at the employment trough. If we expand our timeframe back to the employment peak in January 2008 we get a chart that looks like this.

This chart tells a very different story. We’re still down 4.6 M private sector jobs from the employment peak in January 2008, compared to down 407,000 government jobs. For every net lost government job since employment peaked in January 2008, the U.S. economy has lost more than eleven private sector jobs.

That’s the opposite story from the one told by the President. While the U.S. economy has been slowly creating private sector jobs over the past 2 1/4 years, the hole left to fill is overwhelmingly one caused by the destruction of private sector jobs.

The President is right that the public sector is not creating net new jobs because of local layoffs. But by focusing on recent trends and ignoring the nearly nine million private jobs lost before his measurement window began, he is leading us to the wrong conclusion. Even if government job growth were to resume, our economy needs to create millions more private sector jobs to be restored to full health.

My charts understate the size of the employment gap because they only measure the decline from January 2008. To return to full employment we need to account for population growth since January 2008, so we need more than 4.6 M new private jobs.

The private sector is not fine, in absolute or relative terms.

Why delay deficit reduction?

Lefty and Righty are debating stimulus and austerity over a cup of coffee.

Lefty: Growth of the U.S. economy is slowing due to insufficient domestic demand and headwinds, especially from Europe. We need to make sure we don’t make the same mistakes as those Europeans who are weakening their economies through austerity. I’m for growth now. We need to increase highway spending, hire more teachers and policeman, and prevent tax increases, except for on the rich.

Righty: I’m not sure I agree with your diagnosis but want to focus on your “growth now” point. Why does it have to be either-or? Why can’t we pursue growth policies and austerity policies simultaneously? You and I disagree both on what policies best lead to increased economic growth and on the best way to address our underlying fiscal problems, but I don’t see why we have to choose between the two goals.

Lefty: Because austerity hurts economic growth and because our need for growth policies is urgent. We need to prioritize growth now because the economy is weak now.

Righty: I’m not being clear. I agree that the short-term outlook is for weak growth at best, and I don’t want to do anything to hurt that.

Lefty: Except you want to slash government spending. That will have a countercyclical effect. Not only will teachers and policemen be laid off, they won’t have income to spend and so shop clerks and plumbers will lose business.

Righty: You and I disagree about the magnitude of that effect. You think it’s big, I think it’s small, and some of my associates think it’s zero. But let’s assume for the moment that you’re right. My principal focus is not on cutting today’s spending. My top austerity priority is to reduce future deficits by reforming and slowing the spending growth of the the big 3 entitlements: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Lefty: Your House Republican friends left Social Security reform out of their budget.

Righty: Yes they did, and I wish they hadn’t. But my point stands — I want to fix our government’s unsustainable borrowing path by making big changes to medium and long-term government spending, especially in the big 3 entitlements. In any conceivable reform those changes don’t even begin for a few years, and once they do, the spending “cuts,” as you call them, phase in gradually over time. I propose policy changes that have no effect for the next few years, then a small effect for a few years. It then grows gradually over time to have huge long-term effects.

Lefty: You want to destroy Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

Righty: That’s a cheap shot and you know it. For the moment let’s set aside the specific changes I want to make. My argument holds even for a very different type of austerity package.

I think that in the long run you want to make only minor tweaks to those entitlement spending programs and instead rely heavily on tax increases to reduce future deficits. I’m just guessing, though, because the only thing you ever say is …

Lefty: I want a balance of spending cuts and tax increases to address our long-term deficit problems.

Righty: Right on cue, thank you. You’re always a bit light on the specifics of your long-term tax increases. But let’s suppose you had specifics. Like mine, your austerity package would have little fiscal effect immediately, and, like mine, your package would phase in gradually over time. This is true if you only raise taxes or if you combine incremental entitlement spending reforms with tax increases. The fiscal effects start small and build up slowly.

To achieve its principal goal, the austerity, also known as deficit reduction, package does not have to have any immediate fiscal effects. I’ll tell you what: you pick a delayed start of up to five years, however much time you think we need for the economy to fully recover and for us to return to full employment. I’ll commit right now that whatever deficit reduction we negotiate will not begin until we are past your initial delay as long as we actually solve the long-term problem. That way, in your Keynesian view of the world, our austerity / deficit reduction package won’t hurt our prospects for short-term growth.

Lefty: So growth now, austerity later? I’m good with that. Always have been. In fact, that’s what I have been saying, if only you had listened more closely.

Righty: Right. I think we both know what each of us wants for short-term economic growth. As I said, I’ll start the deficit reduction discussion with the House-passed Ryan plan + Social Security reform, with a delayed start date of your choosing of up to five years. What is your opening for deficit reduction?

Lefty: Well, I have already proposed $4 trillion of deficit reduction over the next 12 years…

Righty: … which would still leave more than $6 trillion of increased debt over the next decade. And that includes only the beginning of the steep part of the entitlement spending curve. Your proposal would still leaving a massive medium-term increase in debt. My plan would solve the long-term fiscal problem. You don’t like its effect on Social Security and the health entitlements. Fine. What is your solution to the long-term fiscal problem, rather than your first step toward a solution?

Lefty: I’ll tell you later.

Righty: What?

Lefty: I’ll tell you later, when we negotiate austerity, maybe in 2013 or 2014, whenever we’re past this short-term economic weakness. Or maybe we’ll just negotiate this first austerity step after the economy has recovered, and then tackle the rest sometime after that. You said it: growth now, austerity later. I’ll tell you my complete solution later.

Righty: No, no, no. We need to negotiate both now.

Lefty: But you said growth now and austerity later!

Righty: I was talking about implementation dates. We need to agree to both sets of policies now, or at least soon. I am committing that the implementation of whatever austerity we agree to won’t begin until after your delay. We negotiate growth now and austerity now. The growth policies are enacted now and start taking effect now. The austerity policies are enacted into law now but don’t begin to take effect for a few years.

Lefty: Why not wait to negotiate austerity? Growth is more urgent, and we both know how hard it will be to reach agreement on solving our long-term fiscal problem.

Righty: My biggest reason is that I lack confidence in anyone’s promises that they will make hard decisions and cast hard votes at some unspecified future date. But let me invert your question: why wait to negotiate on austerity?

Lefty: Because I don’t want to slow growth.

Righty: But enacting legislation soon to reduce future spending, on a time delay, isn’t going to slow short-term growth, especially in your Keynesian view of the world.

Lefty: If it doesn’t start to take effect for 3-5 years then we have 3-5 years to negotiate.

Righty: No we don’t, because markets are forward-looking and so are people. There is an immediate and significant market benefit in committing the U.S. to a fiscally sustainable path as soon as possible. And people need time to plan for big future changes in old age retirement and health promises.

Lefty: Well we’re not going to be able to negotiate either growth or austerity before the election. It’s too risky.

Righty: You’re probably right, and I’m not locked into any particular timing. The sooner the better. If sooner means right after Election Day, then I’m good. If it means early in 2013, immediately after concluding a short-term negotiation or a new President Romney takes office, I can live with that, too. I don’t need short-term growth and long-term austerity to be negotiated simultaneously or enacted as part of the same legislation.

But it’s crazy to argue that we must wait for the short-term economy to recover before we enact long-term changes that reduce future deficits. The constraints on proposing, negotiating, and enacting long-term deficit reduction are political and legislative, not economic. A weak short-term economy is not a valid excuse for delaying the legislative enactment of policy changes that would solve our deficit and debt problem. It is an excuse only for beginning the immediate implementation of those policy changes, and we can delay that implementation to address short-term growth concerns. Long-term austerity can be proposed, negotiated, and enacted while the short-term economy is weak and even if it is getting weaker.

Lefty: Umm…

Righty: Will you therefore put on the table now a delayed-start austerity plan to compare to mine? If this coming election is to be a choice about two different visions of America, will you present your long-term fiscal vision now so voters can compare our plans? If not, will you commit now to proposing a specific long-term austerity plan no later than January 2013 with a goal of concluding negotiations within a few months? There is no good policy reason to wait longer than that, even if the U.S. economy is in the tank.

Lefty: <Lefty looks at his watch.> Oh my! Look at the time. I am so sorry to rush out on you but I am late for another meeting. I’ll catch you next time. <Lefty shakes Righty’s hand and hurries out.>

Righty: <sigh>

(photo credit: mementosis)

The Obama spending binge

Nine days ago Mr. Rex Nutting of MarketWatch wrote a provocative column titled “Obama spending binge never happened.” Here is the key quote:

Over Obama’s four budget years, federal spending is on track to rise from $3.52 trillion to $3.58 trillion, an annualized increase of just 0.4%.

Referencing and relying on this article (rather than on the hundreds of talented OMB career staff who sit nearby), White House Press Secretary Jay Carney told reporters:

I simply make the point, as an editor might say, to check it out; do not buy into the BS that you hear about spending and fiscal constraint with regard to this administration. I think doing so is a sign of sloth and laziness.

President Obama then followed suit in a campaign speech in Iowa one week ago:

But what my opponent didn’t tell you was that federal spending since I took office has risen at the slowest pace of any President in almost 60 years.

President Obama and Mr. Carney are both relying on Mr. Nutting’s key quote above. Let’s examine the quote as Mr. Carney suggests we should do.

Problem #1: The President argues that his fiscal stimulus law, enacted in February 2009, had a big positive effect on the growth rate of the economy. We are now asked to believe that President Obama’s policies did not significantly increase spending but did significantly increase economic growth. This is, to say the least, an intellectually inconsistent argument. The whole Keynesian fiscal stimulus argument is premised on a significant increase in government spending.

Problem #2: Mr. Nutting assumes that since a President serves a four year term he should be measured for four budget years. But since budget years begin in October and Presidential terms begin in January, the fairest and most accurate way to measure the budget effects of a one-term President is to look at five budget years, not four.

Mr. Nutting mistakenly assumes that FY 2009 spending must “belong” to either President Bush or President Obama. As I explained a while back, the two Presidents should share responsibility/blame for this transition year, since each influenced the spending within it. A form of FY 2009 spending should count in both of their records. The same is true for any budget year that spans a Presidential transition.

The easiest way to see the flaw in Mr. Nutting’s four year budget window is that his 0.4% average annual growth rate assumes the Obama Presidency began on October 1, 2009. That can’t be right.

Problem #3: Beginning measurement eight months into a Presidency would be bad under any circumstances, but in this case it’s critical. The year Mr. Nutting excludes is the financial crisis year, when government spending spiked because of bailout costs for the banks, AIG, Fannie & Freddie, and the auto manufacturers, as well as the first year effect of President Obama’s stimulus law.

Mr. Nutting therefore measures the growth rate not just from the wrong date, but relative to a spending level that was extraordinarily high because of one-time events. Any spending growth rate, over any timeframe, measured relative to the $3.52 trillion starting point of FY 2009 will look good because that starting point is so unusually high. Mr. Nutting cherry-picked his start date to make President Obama’s record look good.

The start/end point gimmick is not a new tactic. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz did something similar with job creation two years ago.

Problem #4: Mr. Nutting mistakenly uses $3.58 trillion to represent the President’s budget for FY 13. This is CBO’s projected baseline spending (i.e., current law spending), not their estimate of what President Obama has proposed. The correct number for the President’s FY 13 proposed spending is $3.72 trillion. (See Table 2 here.)

So in the key Nutting quote upon which the President relied:

- “Obama’s four budget years” should be five;

- $3.52 trillion skips all spending increases in the first eight months of the Obama Administration, including the early implementation of the stimulus law;

- $3.58 trillion is a simple factual error;

- and the calculated 0.4% average annual growth rate depends on all three of the above.

If you instead do this calculation the right way and measure the average annual growth rate from FY 2008 to CBO scoring of the President’s budget proposal for FY 2013, you get an average annual growth rate of federal spending of 4.5%. That’s a nominal growth rate, so the real growth rate will be in the 2s.

As I describe, below you should be careful even using my number because growth rates are an incomplete and therefore inaccurate measure of spending.

Problems 1-4 above reveal the core fiscal policy lesson, which as best I can tell no one else has publicly revealed: don’t rely only on growth rates.

Problem #5: It is a mistake to judge a fiscal policy only by looking at growth rates. At a minimum you need to look at both levels and growth rates. The best thing to do is to examine average levels over time. The spending levels reveal more useful information, and it’s nearly impossible to gimmick spending levels as the Nutting article gimmicks spending growth rates.

The second most important gimmick in the Nutting article is his choice of FY 2009 as his starting point for measurement. The most important gimmick is his choice of an average annual growth rate as the right metric for spending. You calculate an average annual growth rate by picking a starting point and an ending point, drawing a line between them, and then figuring out the slope of the line.

- This works fine if the path you’re measuring is a smooth line or even a smooth curve. The more irregular the path, the more your choice of endpoints affects the measurement of the slope. Mr. Nutting took advantage of that arithmetic fact here by choosing his start point to make President Obama’s spending growth look surprisingly low, but even someone not trying to spin you would be relying too heavily on judgment calls about the appropriate start and end points. The 4-vs-5 years debate matters a lot if you’re measuring the slope of the line, and much less if you’re instead measuring levels.

- The average annual growth rate metric also ignores all the intervening years and therefore loses a lot of potentially useful information. Measuring average levels over time includes this information.

- As a policy matter we should care about how much government is spending (the level), and whether based on our values we think that amount is too much, too little, or just right. If properly calculated, growth rates can be a useful shorthand to allow us to evaluate how levels are changing over time, but growth rates are useless if we don’t understand the levels. A 5% growth rate from a historically high starting spending level is a very different animal than the same growth rate from a much lower starting level.

Conclusions

I will conclude with some facts.

- The historic average is federal spending of 20% of GDP, +/- 0.2 percentage points depending on when you start your measuring window. That’s pre-2008 crisis, so I’m ending the measurement with FY 2008.

- Federal spending averaged 19.6% of GDP for President Bush before the crisis year of FY 2009. If you include FY 2009 in President Bush’s average, including the Obama stimulus and the appropriations laws President Obama signed, Bush’s average is 20.1%.

- The highest level since the end of World War II, pre-financial crisis, was 23.5% of GDP in 1983.

- In FY 2009, the financial crisis year that spanned the Bush and Obama presidencies, federal spending was 25.2% of GDP.

- If President Obama’s FY 13 budget is enacted as he proposed it, during the first term of an Obama presidency spending will average 24.1% of GDP. If for some reason you want to exclude FY 2009 as Mr. Nutting did, your average is still 23.8% of GDP for a one-term Obama presidency.

Federal government spending in the first year of the Obama Administration was extremely high, and much of that was either put in place before President Obama took office or was out of his control. Nevertheless his policies have maintained an extraordinarily high level of spending through his first term, and he proposes to continue to do so if elected to a second term.

Federal spending has averaged 20% of GDP for decades. President Obama is presiding over a much bigger government, at 24% of GDP. If his latest budget were enacted in full and he were elected to a second term, the average over his tenure would be 23.4% of GDP. This means that, relative to the economy, federal government spending would be 20 percent larger than the historic average during a one-term Obama presidency and 17 percent larger than average during a two-term Obama presidency.

That is a spending binge.

(photo credit: Purple Slog)

Government doesn’t give tax cuts, it takes more or less taxes

Wednesday the President spoke to a college crowd in favor of raising taxes on the rich to subsidize low interest rates on student loans. His comments provide an opportunity to explain the signficance of how one talks about taxes.

THE PRESIDENT: How can we want to maintain tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans who don’t need them and weren’t even asking for them? I don’t need one. I needed help back when I was your age. I don’t need help now. (Applause.) I don’t need an extra thousand dollars or a few thousand dollars. You do.

Let’s assume you agree with the President — that a college student has a greater need for an extra thousand dollars than a rich person. By itself that judgment does not mean that raising taxes on the rich to further subsidize student loans is good policy. To make a balanced decision you also need to incorporate the harm done by taking money from someone, a factor the President’s quote ignores because it treats tax cuts as given rather than taxes as taken.

The President’s language assumes this thousand dollars originates with the government and that policymakers must choose either to give it to students to help pay for college or to give it to rich people. Under this logic since we agree that the college students have a greater need, government should give the money to them. In this framework resources belong to the government, the government should allocate those resources according to need, and the government gives tax cuts to people only when government officials determine these people need them.

This approach ignores that government gets this thousand dollars to spend only by taking it from someone. This act of taking has costs — it harms the person from whom the government took the money and it weakens incentives to work and invest.

Am I drawing too strong of an inference from a single Presidential comment at a rally with a bunch of college kids, in which he doesn’t even say “give,” he says “maintain”? I don’t think so. A search of whitehouse.gov for “give tax cuts” turns up 171 hits. Throw in “giving tax cuts” and you get another 77. Yesterday’s Presidential remark emphasized the need comparison, while the giving tax cuts approach is a common Presidential refrain and one of his frequent underlying themes.

You may still think the President’s proposed policy makes sense — that the harm done to the rich guy by taking his money, combined with his need for it, is less than the college student’s need. I’m OK if you reach this conclusion since you included in your evaluation the harm done to the person from whom the taxes were taken. Maybe you assigned little value to it, but you did not ignore it completely. President Obama appears to ignore this cost. The same is true every time you hear an elected official refer to “giving tax cuts” to someone. If we accept that government gives tax cuts, then when government does not give tax cuts, no harm is done since no action is being taken. If instead we acknowledge that government is taking more from someone, we must recognize the cost of that taking in our decision.

Government doesn’t give tax cuts, it takes more or less taxes.

The President’s language puts us on a slippery slope. Under this approach we treat all tax revenues as if they originate within the government. We create moral parity between giving tax cuts and increasing government spending. We trust government officials to reallocate society’s resources to those whom they determine most need it while ignoring the harm done by the taking. By ignoring this harm we set no limiting principle on the government’s ability to take that which we earn and own and give it to others. We make the rich pay more since they have greater ability to pay and less need.

At the end of this slippery slope we find a general principle:

From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.

Karl Marx (Critique of the Gotha Program, 1875)

(photo credit: White House photo by Chuck Kennedy)

America’s entitlement spending problem

I want to highlight two points from the Reports of the Social Security and Medicare Trustees, released Tuesday.

Point 1: If you do not change Social Security’s promised benefit payouts you would need to set aside $23.2 trillion today to permanently fill the hole between promised Social Security benefits and dedicated Social Security taxes (almost all of which are payroll taxes).

For comparison $23.2 trillion is about one and a half years of U.S. GDP. Take the entire economic output produced in the USA for the next 18 months. Set it aside. Now you have enough cash, when combined with future projected Social Security payroll and other dedicated taxes, to pay current and future benefit promises. That’s a mighty big hole to fill.

For the technicians, the present value of the infinite horizon liability is $20.5 trillion, but that assumes one will magically find $2.7 trillion of change under the couch cushions to “pay back the Social Security Trust Fund’s obligations.” The concept I’m trying to capture with the $23.2 trillion is the cash needed now to defease the Social Security liability: suppose you were going to give someone all future revenues dedicated to Social Security, and they would commit to forever paying all promised Social Security benefits. How much additional would you have to pay someone today to accept this deal? I think that’s the appropriate way to measure the size of the Social Security funding gap.

Point 2: For the next two decades demographics are a bigger driver of entitlement spending growth than is health cost growth. Here are the Trustees:

Through the mid-2030s, population aging caused by the large baby-boom generation entering retirement and lower-birth-rate generations entering employment will be the largest single factor causing costs to grow more rapidly than GDP. Thereafter, the primary factors will be population aging caused by increasing longevity and health care cost growth somewhat more rapid than GDP growth.

There is an incorrect and misleading conventional wisdom that health care costs are the principal driver of our long-term entitlement spending problem. That’s true, but only starting about 20 years from now. For the next two decades demographics, specifically the retirement of the Baby Boomers, is the biggest driver of entitlement spending growth. The point that everyone misses is that Medicare (and Medicaid) spending growth are driven by a combination of health cost growth and demographics. When you combine the demographic factor driving part of Medicare spending growth with the demographic cost driver of Social Security, you account for more of the total spending growth than if you look only at the effect of per capita health spending growth.

Health cost growth dominates everything in the long run, but on our current path we won’t make it to the long run. If policymakers do not change the spending paths of Social Security and Medicare (and Medicaid, but that’s not in these reports) soon, things will break long before we get to the time when health costs are the principal driver.

This conventional wisdom and confusion result from two factors:

- People ignore the demographic drivers in Medicare spending. Medicare grows because there are more seniors collecting it and because spending per senior is growing unsustainably fast.

- Advocates for the Affordable Care Act, including President Obama and his former budget director Peter Orszag, worked hard to convince people that “It’s all about health cost growth.” This served two of their purposes: to make an argument for their health care reform proposal and to rationalize not doing anything to fix Social Security.

I am not arguing that we should ignore health cost growth; just the opposite. It is a huge driver of short-term entitlement spending growth, it’s just not the biggest factor in the next two decades. Instead we must change policy to address both demographics and health cost growth, and we must address demographics in all three major entitlement programs: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

(photo credit: RenoTahoe)

It’s not a markup if you don’t vote

The Congressional Budget Act requires the House and Senate to pass a budget resolution by April 15th. Under Democratic control the Senate has not done so since 2009.

Last year Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D-ND) committed to his ranking member, Senator Jeff Sessions (R-AL), that the committee would mark up a budget resolution this year. By itself that’s only a first step but it’s a lot more than the Senate has done in the past three years.

Senate Majority Leader Reid (D-NV) has repeatedly said that he will not bring a budget resolution to the floor this year. If Leader Reid were to carry out such a threat he would be violating the Budget Act requirement, but until now the issue has been moot. As long as the committee has not reported, the responsibility to act and blame for legislative inaction falls on Chairman Conrad. If the committee reports a budget resolution then the responsibility for action and blame for inaction shift to Leader Reid.

Chairman Conrad’s announcement

Today Chairman Conrad announced that:

<

ul>

I imagine Chairman Conrad will receive favorable press coverage for proposing the bipartisan Bowles-Simpson recommendations. If he doesn’t use his power as Chairman to force a vote, however, then his proposal is little more than an interesting debate topic.

Unless I’m missing something Chairman Conrad is not marking up a budget resolution tomorrow. He is instead convening the committee for a discussion. He will lay down the Bowles-Simpson numbers as his own and everyone will talk. Then he will adjourn the meeting tomorrow without any votes, without any date to reconvene, without any deadline or forcing action for private bipartisan negotiations he hopes will then occur but for which he has low expectations of success.

It’s not a markup if you don’t vote.

Talking vs. voting

The job of a Member of Congress is to vote on legislation, not to talk about legislation. Talk is sometimes helpful but If Members of Congress are not voting they’re not doing their job.

Press coverage often equates public statements with votes. That’s a huge mistake. While it’s easy to speak against a policy you oppose, casting a vote against it increases the public pressure on you to support an alternative and cast an affirmative vote for it. Even failed votes can drive legislative progress by pressuring members to say what they’re for, not just what they’re against.

For a few years the Senate has had a problem of talking rather than voting, especially on fiscal policy.

- Leader Reid is not blocking a budget resolution reported by the Budget Committee. He is saying he will block a budget resolution if one is reported by the Committee.

- Leader Reid says he won’t bring a budget resolution to the floor because he knows that it would be impossible to reach a conference agreement with those wild and crazy House Republicans. If the committee were to report a budget resolution, then Leader Reid would be forced to back up his verbal threat with a procedural decision not to bring the resolution to the floor. The threat and the decision to enforce that threat are fundamentally different, because the threat could be a bluff or the conditions surrounding the decision could change when it’s confronted.

- The Senate Democratic majority has for three years verbally attacked the House-passed budget resolutions but has not marked up a budget resolution in committee or brought one to the Senate floor. Senate Democrats have talked but not acted legislatively, and as the majority they have primary responsibility to act.

- It appears Chairman Conrad plans to propose a budget but not to force any Members of his committee to vote on it. Instead everyone will just talk about his proposal.

Senate Republicans are not blameless here. For three years they have justifiably attacked the Democratic majority for failing to uphold their responsibility to pass a budget, but the Senate minority has not offered their own budget resolutions. The primary responsibility for action rests with the majority, but the minority has opportunities to act and to force votes as well, especially in the Senate. Senate Republicans have generally chosen not to do so. They have, however, talked a lot.

To their credit both the House majority and minority(!) have proposed and voted on budget alternatives. House Republicans have done so each year since they regained the majority, and this year even House Democrats, led by Committee Ranking Member Van Hollen, offered an alternative budget and forced a floor vote. I strongly oppose the substance of the Van Hollen amendment but House Democrats at least deserve credit for putting their votes where their rhetoric is. House Republicans deserve extra credit for carrying out their legislative responsibilities and taking electoral risk while knowing that the Senate was unlikely to to the same.

Tomorrow’s Senate Budget Committee discussion

It is possible that tomorrow’s discussion will lead to a sudden outpouring of bipartisan legislative action in the Senate. The Gang of Six, who fouled up the Obama-Boehner grand bargain negotiations last year with their weak policy and poor timing, have a chance to redeem themselves by supporting the Conrad mark and demanding the committee and full Senate vote on it. They could form the beginning of a legislative center that could pressure both party leaders to act. I oppose the Bowles-Simpson recommendations because they would result in too big of a federal government, but nonetheless I think that voting on Senator Conrad’s implementation of those recommendations would represent legislative progress. At least members would be making choices and backing them up with votes, and I would hope that Senate Republicans would then propose an alternative that would be more to my liking.

If tomorrow Chairman Conrad does not use the power he has to drive the process forward I don’t see why we should anticipate any legislative progress. Last fall the Super Committee had a formally binding process and a fixed deadline and they failed to negotiate a compromise. This is now an election year. Chairman Conrad has missed his deadline and appears unlikely to create a new one. He seems resigned to the likelihood that his proposal will go nowhere, but that is in large part a result of his apparent decision not to force either the committee members or the full Senate to vote on his proposal.

The Senate has spent three years talking about fiscal policy. Senators have a responsibility to vote on specific proposals even if they know those votes will fail. As Budget Committee Chairman it is Senator Conrad’s responsibility to force the Senate to act, not just to offer an interesting proposal for discussion.

(photo credit: Talk Radio News Service)

Subsidizing wind and solar because China and Germany are doing it

Here is President Obama speaking in Ohio Thursday:

We also need to keep investing in clean energy like wind power and solar power.

… And as long as I’m President, we are going to keep on making those investments. I am not going to cede the wind and solar and advanced battery industries to countries like China and Germany that are making those investments. I want those technologies developed and manufactured here in Ohio, here in the Midwest, here in America. (Applause.) By American workers. That’s the future we want.

The President has picked three industries and is arguing for an industrial policy to subsidize them in part because other countries are subsidizing them.

Let’s extend this logic. Suppose China or Germany starts subsidizing the biotech industry. Should the U.S. government subsidize American biotech firms so that “those technologies [are] developed and manufactured … here in America, by American workers?”

What if China subsidizes web development firms, Germany subsidizes auto manufacturers, France subsidizes biotech firms, Japan subsidizes advanced battery firms, Brazil subsidizes ethanol firms, and South Korea subsidizes chip manufacturers? Should the U.S. subsidize all of those domestic industries so that we don’t cede any of them?

What if the Canadian or Mexican government were to subsidize high-tech oil production firms, or Brazil to subsidize advanced tobacco production? Is the President’s policy to keep here in American through subsidies all industries that other governments are subsidizing, or only the “good” industries that he thinks should be kept in America?

More generally, should the U.S. government (a) subsidize particular industries and if so (b) determine those subsidies based on what other countries are doing?

If we are to subsidize particular industries over others, how do we square that with the argument, made by the President and others, that we need to remove such subsidies from the tax code?

If the rule for structuring subsidies is to make sure we don’t cede certain industries to other countries, how is that different from giving the governments of those countries control over the shape and structure of the U.S. economy?

If the President wants to subsidize wind and solar power because he wants to accelerate the development of carbon-free alternatives to coal and natural gas, he should make that argument. If President Obama is instead going to subsidize industries either because he likes them or because other Nations’ governments are subsidizing them, then we must acknowledge that he is engaged in industrial policy, aka state-managed capitalism, with an open question about whether the managing state is based in DC, Berlin, or Beijing.

(photo credit: Maryellen McFadden)

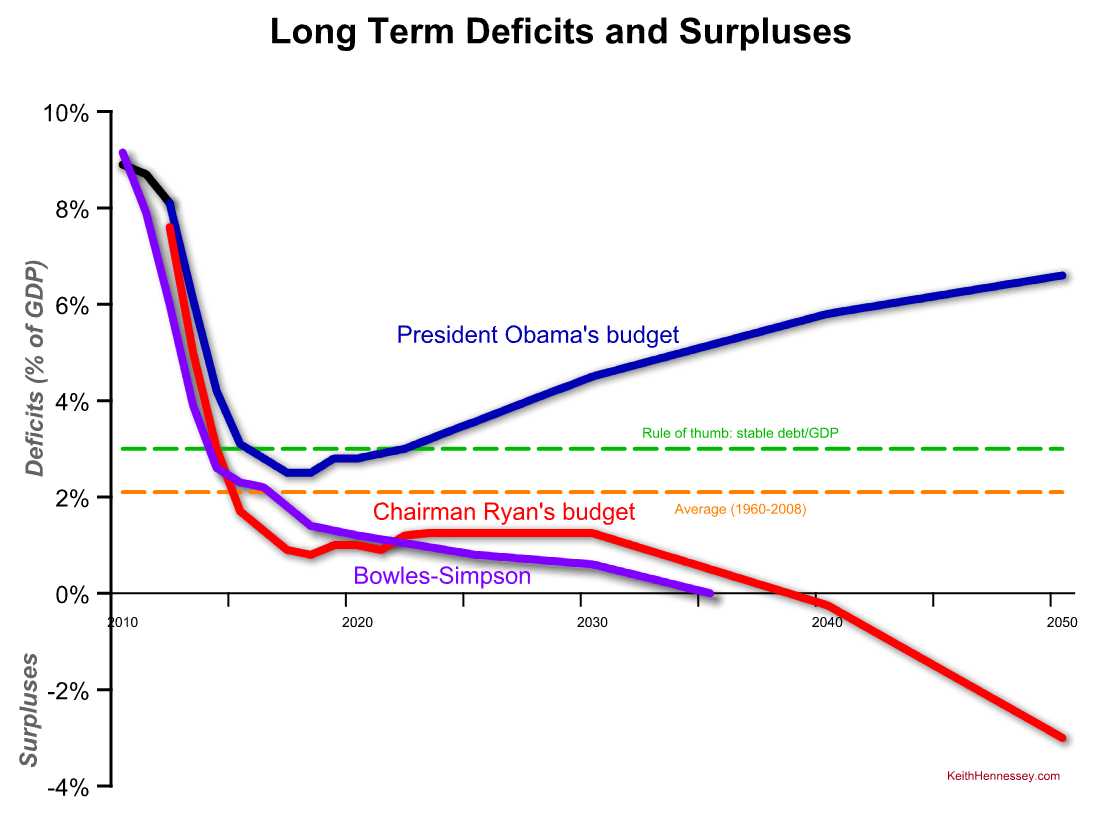

Comparing the Ryan and Obama deficits to Bowles-Simpson

Here is the series so far:

- President Obama’s proposed medium-term deficits

- The Ryan budget proposes lower deficits and less debt than the Obama budget

- How will President Obama respond this year to Chairman Ryan’s lower deficits and debt?

- Comparing the Ryan and Obama long-term deficits and debt

Yesterday I showed you the long term deficit and debt paths for both Chairman Ryan’s and President Obama’s budgets.

Today will be easy. I’m just going to add the Bowles-Simpson long-term deficits in the mix.

In early 2010 President Obama created a bipartisan fiscal commission co-chaired by former Clinton White House Chief of Staff Erskine Bowles (D) and former Wyoming Senator Alan Simpson (R).

Although Messrs. Bowles and Simpson failed to get the 14 of 18 vote 3/5 supermajority the President required of them, I maintain that they succeeded. They build a bipartisan plan that would have significantly reduced future budget deficits and that quite surprisingly had support from Senate Democratic Whip Durbin (D-IL),Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D), the then-ranking Democrat on the House Budget Committee, John Spratt, and Republican Senators Coburn, Crapo, and Gregg.

The President did nothing with the recommendations of this commission that he created.

Here are the long term deficit paths from yesterday with one addition: the Bowles-Simpson recommendations are a new purple line.

The long-term deficit story is fairly clear. You can see that the purple line ends up below the red line and the two track closely together. Bowles-Simpson is therefore slightly more aggressive on deficit reduction than the Ryan budget in the long run. Bowles-Simpson and Ryan have quite similar deficit paths, both of which are sustainable in the long run and are therefore quite different from the President’s proposed long run path.

Having similar deficit paths is not enough for us to adequately compare the Ryan and Bowles-Simpson plans. To do that at a minimum we need to look at the gross spending and revenue components of each plan. We’ll get to that next week.

For now we can draw two conclusions by adding the Bowles-Simpson plan to this graph:

- The Ryan and Bowles-Simpson plans have similar deficit paths.

- It is silly to claim, as President Obama’s team does, that President Obama’s budget is similar to Bowles-Simpson, at least in terms of long term deficit reduction. Bowles-Simpson is a fiscally sustainable long run path while the President’s budget is not.

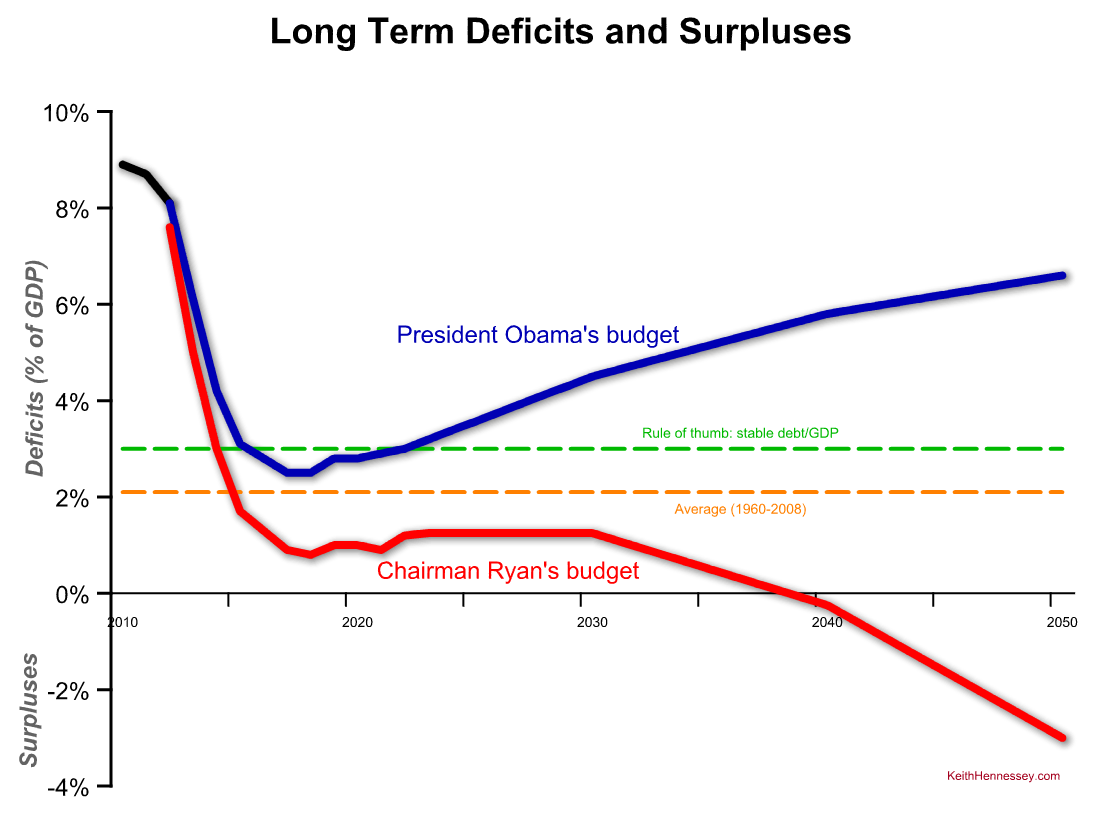

Comparing the Ryan and Obama long-term deficits and debt

Monday I showed you President Obama’s proposed medium-term deficits. Yesterday I compared those with Chairman Paul Ryan’s medium-term deficits, then did the same comparison for medium-term debt. Today I’d like to do the same thing but with a longer timeframe.

In case you missed it here are the earlier posts in this series:

- President Obama’s proposed medium-term deficits

- The Ryan budget proposes lower deficits and less debt than the Obama budget

- How will President Obama respond to Chairman Ryan’s lower deficits and less debt?

There is uncertainty in every budget projection, and every projection requires making certain assumptions. The longer your timeframe the more your projection is vulnerable to those uncertainties and assumptions. In addition the policy specificity in both plans declines significantly after 10 years.

Despite all these caveats, it makes sense to look at long run projections. Yes, they are inaccurate, and yes, things will change in both the economy and policy. But that’s no reason to ignore our best guess/estimate of what trends each leaders is proposing. As long as we don’t assign too much false precision to multi-decade projections we can still draw valuable conclusions from these long-term estimates.

Here is the long-term deficit comparison.

- Once again you can see that both budgets project declining deficits (relative to the economy) for the next six years (through 2018).

- Ryan’s deficits then tick up a big to 1.25%, hold flat until 2030, then begin a steady decline, reaching balance in 2039 and a 3% surplus by 2050.

- After ten years President Obama’s deficits begin to climb steadily over time, reaching 6.6% of GDP by 2050.

I am using each advocate’s claims about their long-term projections. The impartial referee has not scored the policy effects of either proposal beyond 10 years, so we have to rely on the advocates’ claims.

Would we reach a 3% surplus in 2050 if the Ryan budget were enacted in full? Certainly not. Would we hit a 6% deficit in that same year under the President’s budget? No. At 40 years out, each is little more than an educated guess.

But the long term lessons of this graph are not guesses.

- Chairman Ryan proposes stable deficits of a bit over 1% of GDP, below the historic average deficit, followed by a gradual path to balance and eventually to surplus.

- President Obama’s budget would result in deficits that are always greater than the historic average, and that would cause debt/GDP to increase again beginning about 10 years from now.

- The gap between the two proposed deficit paths widens over time.

- President Obama’s proposed deficit path is unsustainable. Our economy can tolerate high and even very high deficits for a short time. High and steadily rising deficits like those described by the blue line cannot be sustained. Something in the economy will break.

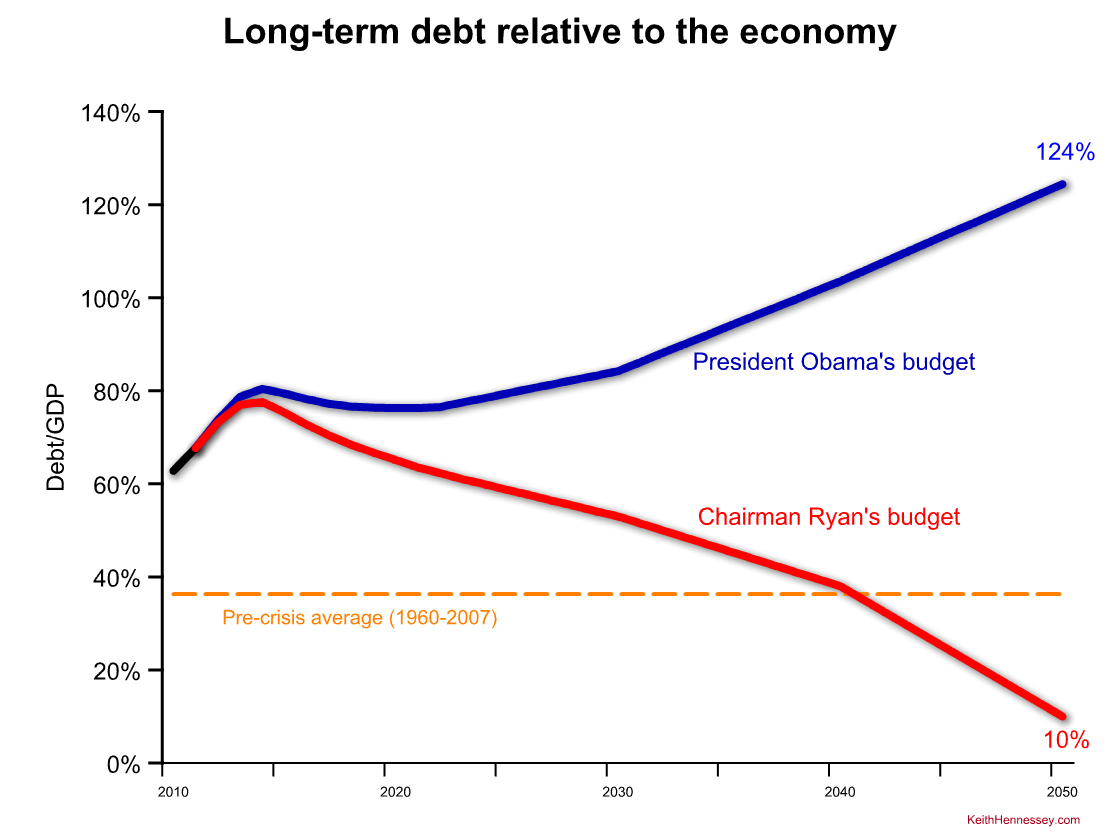

Now let’s look at long-term debt. Debt is, of course, the accumulation of annual deficits and occasionally surpluses. Deficits measure an annual flow while debt measures a stock.

The divergent paths are even clearer here. Under both plans debt/GDP would increase this year and next, then begin to decline.

Chairman Ryan’s plan would result in debt/GDP steadily declining over time. It would take decades to return to a pre-crisis average.

President Obama’s plan would result in debt/GDP stabilizing by the end of this decade, then steadily and forever growing. At some point, and no one knows when, that debt becomes unsustainable.

Again, please don’t get too wrapped up in the point estimates I have shown for each plan for 2050. The point is that the Obama debt would eventually break 100% of GDP and keep climbing, and the Ryan debt would steadily decline over time. The gap between the two is significant and ever-increasing.

The red path is economically sustainable, the blue path is not.