The price of politics: a bit over $1 trillion

At almost every recent campaign stop President Obama has said a version of this:

Independent analysis shows my plan for reducing the deficit would cut it by $4 trillion. I’ve already worked with Republicans in Congress to cut a trillion dollars’ worth of spending, and I’m willing to do more.

Here is an excerpt from Bob Woodward’s new book, The Price of Politics:

Obama was getting fired up as he worked through what to say and how to say it. He wanted a $ 4 trillion deficit plan too, but the cuts were too severe. The progressive and liberal base would be deeply distressed.

Sperling suggested an old trick from the Clinton years: Stick with the $ 4 trillion— that was easy to understand— but instead of projecting it over the traditional 10 years, do it over 12. No one would really notice. Few would do the math. By stretching the plan out and loading most of the cuts into its final years, the early cuts were substantially smaller.

I did the math. When President Obama rolled out his $4 trillion number in an April 2011 speech I wrote:

$4 trillion in deficit reduction over 12 years does not “match” $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years. It’s not even close.

The twelve year timeframe is a red flag. Federal budgets are measured over 1, 5, and 10 year timeframes. Any other length “budget window” is nonstandard and suggests someone is playing games.

… In this scenario, $4 trillion of deficit reduction over 12 years translates into about $2.8 trillion over 10 years.

Three days later, Lori Montgomery of the Washington Post quoted White House spokeswoman Amy Brundage:

Under the administration’s estimates, the president’s framework saves $2.9 trillion over 10 years and $4 trillion over 12 years…

Mr. Woodward’s book confirms my analysis and attaches intent to President Obama’s $4 trillion claim. If Mr. Woodward has it right, President Obama is intentionally misleading you by using this $4 trillion number (while remaining technically correct since he is not now specifying a timeframe).

What about the “independent analysis” cited by the President? He is referring to this February 2012 statement from Robert Greenstein, head of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a liberal think tank. Here is the key quote:

In total, deficit reduction over the coming ten years (fiscal years 2013-2022) — through a combination of the proposals in the budget and measures enacted in 2011 — would equal about $3.8 trillion, not counting savings from reductions in costs for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, according to Table S-3 in the President’s budget.

At first glance it appears this supports the President’s “$4 trillion” number, and may even support a claim of $4 trillion of deficit reduction over 10 years rather than 12. But when we look more carefully:

- We see that Table S-3 in the President’s budget is titled “Deficit reduction since January 2011.” The President is, as Dr. Greenstein acknowledges, counting deficit reduction already enacted into law as if it were part of a new deficit reduction proposal.

- At the same time as the Greenstein statement I wrote about this table, separating out past from proposed future deficit reduction. I came up with $2.764 T of new deficit reduction over 10 years, which is again consistent with the White House’s earlier statement of $2.9 T over 10 years and $4 T over 12.

- Even my $2.764 T is too generous. When you drill down into the details the Administration takes credit for savings that really shouldn’t count. Any measure of deficit reduction is vulnerable to baseline gaming. You should always be wary of claims of deficit reduction.

Let’s return to the President’s quote, which I emphasize he is saying at almost every campaign stop this month. President Obama is boasting about “independent analysis” that simply cites a number from a table in the President Obama’s budget. This is, to me, a new definition of “independent.”

President Obama is not technically lying when he says his budget proposes $4 T of deficit reduction. He is instead using one of two “tricks” to mislead the listener:

- He is using a nonstandard 12 year timeframe to make his proposed deficit reduction appear a bit more than $1 trillion larger over the next decade than it is; and/or

- He is misrepresenting a combination of already enacted deficit reduction with that which he proposes for the future. Re-read the quote up top and tell me if you think “and I’m willing to do more” suggests that he is proposing $4 trillion of future deficit reduction.

If Mr. Woodward is right, President Obama is intentionally using these numbers, these “tricks,” to mislead you. He wants to claim credit for as much deficit reduction as is in the Ryan budget, but he didn’t want to propose the spending cuts and/or tax increases to hit that target: “

I know that this type of analysis is technical and can be challenging. According to the Woodward book, President Obama’s team is counting on that. We are, however, talking about an incumbent President who appears to be intentionally misleading voters about more than one trillion dollars (that’s one million million dollars) of hard policy choices that he has not actually made. I think that’s worth the effort to understand.

To President Obama the price of politics looks to be a bit more than $1 trillion over the next decade.

(photo credit: marshlight)

Tax levels cheat sheet

Here is your tax levels cheat sheet.

- Over the past 50 years federal taxes have averaged 18% of GDP.

- Governor Romney proposes taxes “between 18 and 19 percent” of GDP.

- The House-passed (“Ryan”) budget proposes long-term taxes of 19% of GDP.

- President Obama’s budget proposes long-term taxes at 20% of GDP.*

- The Bowles-Simpson plan proposes long-term taxes at 21% of GDP.

See how nicely that works? 18-19-20-21

There is a danger that measuring tax levels as shares of GDP will lead to casually concluding that “only one or two percentage points difference” is not a big deal. This would be a huge mistake.

- GDP this year will be about $15.5 T. That means each 1% of GDP in higher taxes is about $155 B more taken by the government from those who earn it.

- Going from 19% of GDP to 20% of GDP means a total increase of all federal taxes of just more than 5% (20-19 / 19 = 5.26%)

- For comparison, the ongoing partisan fight over whether to extend today’s tax rates for “the rich” is a fight about half a percent of GDP. The difference between the Ryan and Obama long-term tax levels is twice as big, and the difference between the Ryan and Bowles-Simpson plans is four times as big. Also, the legislative difficulty of closing these gaps is not linear, meaning it is more than twice as hard to close a gap that is twice as large, because policymakers make the easiest changes first.

I intend this rule-of-thumb to be useful for medium-term and long-term fiscal policy discussions, not for short-term debates. Federal taxes are pro-cyclical, meaning that when the economy is weak, taxes as a share of GDP drops. Taxes/GDP is quite low right now, but that’s in part because the economy is still quite weak. The above numbers are what each policymaker has proposed for their long-term tax share of GDP, measured 5-10 years from now. In each case they would start with taxes lower than their long-term share. Taxes/GDP would then gradually climb through the next ten years, stabilizing at the rates specified above.

I put an asterisk after the Obama line. The Ryan and Bowles-Simpson plans would stabilize debt/GDP in the long run, while President Obama’s would not. Since President Obama has not proposed a long-term fiscal policy solution, we don’t know whether his long-term fiscal solution, if he had one, would raise taxes above 20% of GDP.

Few seem to have noticed that Messrs. Bowles and Simpson have proposed long-term taxes that are significantly higher than those proposed by President Obama. The spending component of the Bowles-Simpson plan is between the House-passed (Ryan) plan and the President’s proposal, but it’s much closer to and shaped like the Ryan plan. I think that’s consistent with the political dialogue surrounding it, which sees Bowles-Simpson as a middle ground between the two parties.

But on taxes the Bowles-Simpson plan represents one end of the spectrum, not a middle ground, at least until (if) President Obama proposes a long-term fiscal solution. The tax component of the Bowles-Simpson plan is the highest (“leftmost”) of the three, at least for now. This provokes an interesting question for any elected official, of either party, who says he or she supports the Bowles-Simpson recommendations: “So, as part of a long-term fiscal solution, you’re OK with total tax levels five percent higher than those proposed by President Obama?”

Our long-term fiscal problems are immense, and some elected officials may knowingly choose these big tax increases as part of a package combining spending cuts and tax increases. I wonder, however, if some elected officials who have been attracted by the bipartisanship and centrist optics surrounding the Bowles-Simpson effort understand what they are supporting on tax levels. It would be a shame to unwittingly embrace such a massive tax increase.

(photo credit: David Stillman)

The “insufficient detail” critique of the Ryan budget

President Obama’s former budget director, Dr. Peter Orszag, attacked the Ryan budget in the Washington Post. I’ll respond here to his primary critique.

Dr. Orszag argues that the Ryan budget is not a serious fiscal proposal.

In part because of his winning personality, Ryan … has convinced many in Washington that his budget blueprint is a serious proposal for solving our long-term fiscal problems. Unfortunately, it’s not. Let’s dig into the asterisks of Ryan’s plan and unearth the fine print.

Dr. Orszag’s principal critique is that the Ryan budget is short on details. He argues that the Ryan Medicaid block grant, tax reform, and nondefense discretionary spending cuts, are “capping and punting—limiting spending to a certain level but providing no specifics on how to achieve that number.” Later he argues that the lack of legislative detail creates business uncertainty.

The irony is that while in office neither Dr. Orszag nor his boss, President Obama, proposed any long-term fiscal reforms. Even after enacting the Affordable Care Act, which was purported to significantly address our long-term fiscal problems, the Obama Administration’s own numbers show that we’re still headed toward fiscal collapse.

Paul Ryan is chairman of the House Budget Committee. His day job is to develop and pass through the House a budget resolution, to reach a compromise with his Senate counterpart, and then to pass the compromise budget resolution through the House. For the two years he has chaired the committee Mr. Ryan has done his job, passing House budget resolutions in both years. He has been unable to finish his task because the Senate Democratic majority has not done its budget work the last two years. You can’t negotiate with something that doesn’t exist.

A budget resolution is like a blueprint for a new house. A blueprint specifies the size of the house, how many floors there will be, the sizes of each room, and where the walls will go. A blueprint does not specify where the couch will go in the living room or what color it will be.

While studying the draft blueprint, you and your spouse may not yet agree on the position, style, or even type of furniture to put in each room. Reaching such agreement may be quite difficult, and it may depend on how the rooms look once they are actually built. But to approve the blueprint you don’t need to reach agreement on the furniture details at such an early stage. All you need is to agree that the sizes and shapes of the rooms on the blueprint can accommodate the various detail options you are considering.

In the same way, the Congressional budget process separates debate on the topline numbers of fiscal policy from the legislative details of how those numbers will be implemented. Budget Committee Chairman Ryan’s job is:

- to set overall fiscal goals for the federal government: total government spending, total taxes, and the deficits and debt that result;

- to divide that spending up into about 10 categories (actually it’s divided by committee jurisdiction);

- to set legislative processes that will ensure that subsequent legislation complies with Ryan’s numbers; and

- to get a majority of the House to vote for all of the above.

After this budget resolution (“blueprint”) has been approved, then legislative action shifts away from Chairman Ryan and the Budget Committee and to the various committees responsible for writing legislation. The House Agriculture Committee develops a farm bill. That committee decides the details of how farm policy will be changed, subject to the numeric limits established in Ryan’s budget resolution. The two committees responsible for Medicare write legislation changing Medicare, which is again required to conform with the numbers in the budget resolution. The Ways & Means Committee writes tax reform legislation, subject to the revenue requirements in the Ryan plan.

To do his job, Chairman Ryan is not required to release any reform plans. He just has to produce a table of numbers, and if he does offer any details on how he thinks Medicare or Medicaid or farm subsidies or taxes should be reformed, those details are not binding on anyone. They are merely his suggestions to the committees responsible for writing the legislative details.

Why, then, might a Budget Committee Chairman publicly propose a broad outline of Medicare or Medicaid reform, or a pro-growth tax reform plan, if they are not binding? For two reasons:

- To build support among House Members whose votes he needs for his numbers by showing them sample reform plans consistent with his numbers; and

- To influence the legislative debate that comes later.

When Chairman Ryan approaches you, a House Member, and asks for your support for his budget resolution, you might express concern about the amount his budget “cuts” Medicare spending. Mr. Ryan can then show you a plan he has developed that meets his spending targets and assuages your concerns on the details. If you vote for his budget resolution you are not, formally, voting for the particular Medicare or tax reform plan that Mr. Ryan assumed. You are only voting for the numbers, the spending and tax levels, that would result from such a plan. And if you don’t like the details of how Mr. Ryan might implement any proposed reform, you have plenty of opportunities to withhold your support for the actual legislation when it is later developed by other committees.

Chairman Ryan has, for example, supported two different versions of long-term Medicare reform. In 2011 he proposed eventually moving all new beneficiaries into a premium support system. In 2012 he teamed up with Democratic Senator Ron Wyden to propose a variant in which traditional fee-for-service Medicare would remain as an option for future beneficiaries. The numbers in the Ryan budget plan are consistent with either version of Medicare reform, and support of the Ryan budget plan allows the Congress to negotiate later on which version of reform makes most sense. Or it would, had the Senate Democratic majority done its work and passed a Senate budget resolution instead of punting again this year.

There is therefore nothing “unserious” about specifying only a broad outline for spending or tax reforms as part of a budget resolution. In fact, it’s standard practice for the legislative process.

On some of the specifics attacked by Dr. Orszag:

- Medicare premium support plans like Ryan/Wyden date back to the late 90s. The first of significance was proposed by Senator John Breaux (D) and Rep. Bill Thomas (R) in 1998.

- A Medicaid block grant was passed by a Republican Congress in 1995 and vetoed by President Clinton.

- The Ryan budget proposes revenue neutral tax reform. To find such a plan, visit DC and swing a cat. You’ll hit two or three.

Dr. Orszag is therefore attacking Mr. Ryan for doing his job as House Budget Committee chairman. Dr. Orszag argues that Mr. Ryan is being disingenuous by providing insufficient detail on his policy proposals, when it is Dr. Orszag who is taking advantage of general ignorance of the budget process by suggesting that a budget resolution should offer the detail of implementing legislation. As a former director of CBO and OMB, he knows this.

This is a common ploy in fiscal politics. If your opponent proposes policy details, attack the most unpopular of those details. If he does not, attack his credibility for not providing sufficient detail. The only way to avoid this political trap is to avoid proposing any long-term fiscal policy solution and hope no one notices, as President Obama has done so far.

Dr. Orszag also conflates different types of criticisms of the Ryan budget:

- policy critique: “I oppose policy X in the Ryan budget;”

- legislative critique: “I don’t think policy X in the Ryan budget can get the votes it needs to become law;” or “If it is enacted, policy X will cause too much policy pain and eventually will be repealed;” and

- budget credibility critique: “If all policy assumptions in the Ryan budget were implemented as proposed, the numbers still don’t add up.”

Dr. Orszag opposes Mr. Ryan’s proposals for Medicare reform, Medicaid reform, tax reform, and discretionary spending. That’s fine, he’s entitled to his policy opinion.

Dr. Orszag also predicts that Members of Congress would, now or later, fail to support the amount of policy change needed to hit Ryan’s long-term spending and revenue targets. That’s a political/legislative prediction, and to judge it we also need to ask “Compared to what?” In isolation he is correct that it is quite difficult to get Members to vote for painful spending cuts and/or tax increases. But when you’re on your fourth year of trillion+ dollar deficits and the future looks even worse, that’s what leadership requires – making painful and unpopular policy choices. And when the path you’re on leads to a downgrade of the U.S. credit rating or, at some point, complete fiscal collapse, policy changes that were previously out-of-bounds will look less unattractive.

Dr. Orszag then morphs his policy critiques and legislative critiques into an attack on the credibility of Mr. Ryan and his budget plan, deeming it an “unserious” proposal. There is, however, a huge difference between “I don’t like the policies you propose” and “Your numbers don’t add up, your proposals are not serious.” Yes, the Ryan budget would require significant policy changes from our current path. But since our current fiscal path is headed toward disaster, that’s a good thing.

The Ryan budget is a serious fiscal policy roadmap. It proposes the detail required for its intended legislative purpose, and it offers a roadmap for future reforms. And until President Obama and a Democratic-majority Senate propose an alternative long-term path or are replaced, the Ryan plan is literally the only long-term game in town.

(photo credit: Roger Barone/Talk Radio News Service)

What if it’s a status quo election?

I agree with President Obama that this election is shaping up to be a choice between two conflicting economic visions. What happens, though, if the election results in a stalemate between those visions? What happens to economic policy if President Obama is reelected and Republicans retain their House majority?

The Associated Press’ Ben Feller asked President Obama this question yesterday (highlights by me).

AP: Let’s say you win—okay, that’s a hypothetical that you would probably buy into. But say you win, but the House Republicans win again also, a likely possibility. How is that any different from what we have now? Why wouldn’t a voter look at that and say that’s a recipe for stalemate. How would you do anything differently?

THE PRESIDENT: Well, there are a couple things that I think change. No. 1, the American people will have voted. They will have cast a decisive view on how we should move the country forward, and I would hope that the Republican Party, after a fulsome debate, would say to itself, we need to listen to the American people.

I think what is also true is that because of the mechanisms that have been set up, agreed to by Republicans, that have already cut a trillion dollars’ worth of spending out of the federal deficit, but now we’ve got to find an additional trillion—$1.2 trillion, I guess—before the end of the year, means that the Republicans will have to make a very concrete decision about whether they’re willing to cooperate on a balanced package.

If they don’t, then I’m going to have to look at how we can work around Congress to make sure that middle-class families are protected, but that we’re still doing our—meeting our responsibilities when it comes to deficit reduction and investing in the future.

Here’s my attempted translation:

<

ul>

This sounds like half of a recipe for continued stalemate, the premise of Mr. Feller’s insightful questions. All that is needed to complete the recipe is for members of next year’s House, and maybe Senate, Republican majority to believe that their constituents reelected them in part because of their economic policy views.

Logic problem: if you think the fiscal policy stalemate over the past two years is the result of extreme, crazy, intransigent House Republicans who refused to negotiate responsibly, what makes you think they would behave any differently over the next two years if they retain the majority? Why does President Obama, or why should you the voter, assume that they will change their behavior, given how unreasonable you think they have been so far? Won’t they be just as extreme?

A status quo election likely produces a stalemate in lame duck session fiscal negotiations, at least initially. Neither side will be able to legislatively force the other to cave. President Obama could sustain a veto, and Speaker Boehner could control what legislation is considered by the House. Any legislation would therefore have to be agreed to by both men, as well as by Leaders Reid and McConnell, each of whom would have the legislative strength to block legislation they oppose, no matter which party controls the Senate majority. After a status quo election, the two most likely lame duck scenarios are (1) a negotiated middle ground compromise or (2) a stalemate in which the fiscal cliff bites for a while, increasing pain and pressure on both sides until a compromise is reached.

President Obama’s “work around Congress” language confuses me. The Constitution grants the power of the purse to Congress, not the President. President Obama’s ability to take significant fiscal policy actions without a new law is, at best, extremely limited. In the short run he may have some flexibility to control the terms and timing of a sequester if there’s no lame duck deal, and this may give him a little more leverage in that struggle. But he certainly lacks the unilateral authority to raise taxes or to cut or increase spending beyond the amounts now specified in law. He certainly can’t do anything unilateral to address our medium- and long-term fiscal problems.

Mr. Feller asked the President, “How is that any different from what we have now. … How would you do anything differently?” There is one thing that would be different in a status quo election: President Obama would no longer be constrained by the need to be reelected. He, unlike Members of Congress, would have increased policy flexibility if he chose to use it. He could move to the center, as he did briefly after the 2010 election, and negotiate a short-term or even a long-term fiscal policy deal with Congressional Republicans.

If this is his plan, he isn’t giving any hint of it so far. President Obama could have offered Mr. Feller a game-changing answer by announcing a new substantive position. He could have said, “If House Republicans and I are reelected, I will propose a long-term fiscal policy solution based on the Bowles-Simpson recommendations, and I will negotiate in good faith with anyone willing to work constructively toward solving our long-term fiscal problems. I will seek principled compromise, even with those whose views are different from my own.”

Had he given this answer, he would ally himself with a small centrist coalition in the Senate that supported Bowles-Simpson. This would give a centrist/independent voter a concrete answer to Mr. Feller’s question, and would suggest that negotiations between the same parties might turn out differently next time, that a status quo election might not result in a continued fiscal policy stalemate. Such an answer would, however, upset President Obama’s political base, liberals who dislike the Bowles-Simpson recommendations as much as do most Congressional Republicans.

President Obama can still make such a move. Until and unless he does, President Obama’s answer to Mr. Feller’s question is that, if there’s a status quo election, he would not do anything differently than he has for the past two years of fiscal policy stalemate.

Responding to some of President Obama’s Medicare claims

Let’s examine a few quotes from President Obama’s weekly address, which this week is about Medicare.

<

blockquote>THE PRESIDENT: I saw how important things like Medicare and Social Security were in

Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid are growing at unsustainable rates. The “millions of Americans who are working hard right now” are paying taxes into a system that will be unable to afford to pay the benefits it is promising them today. President Obama says these workers “deserve to know that the care they need will be available when they need it,” but he has not proposed policy changes to produce that outcome.

THE PRESIDENT: We’ve extended the life of Medicare by almost a decade.

No you haven’t. The Affordable Care Act (ACA, also known as “ObamaCare”) slowed Medicare spending growth. The Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund includes less than half of Medicare spending. You can argue that you have extended the life of this trust fund by “almost a decade,” but trust fund accounting ignores a more immediate cash flow problem. Since the HI trust fund contains only IOUs from the government to itself, this accounting ignores the question of where to find the $296 B in cash this year to pay for Medicare spending above that covered by Medicare payroll taxes and premiums. Medicare has never been a fully self-funded program, and even with the savings enacted in the Affordable Care Act, it is still an enormous pressure on the rest of the budget.

And that’s the positive portrayal of what the President and his Congressional allies did, because at the same time they “cut” Medicare spending, they increased spending on new health entitlements in the ACA by the same amount. So the budgetary savings and reduced future deficits they legitimately achieved by slowing Medicare spending were then undone by new government spending. This is why Governor Romney and Mr. Ryan say the President “used Medicare savings to pay for [part of] ObamaCare.”

THE PRESIDENT: And I’ve proposed reforms that will save Medicare money by getting rid of wasteful spending in the health care system and reining in insurance companies – reforms that won’t touch your guaranteed Medicare benefits.

In his budget President Obama proposes to slow spending growth by about $[200] B over the next decades. He then proposes to spend that same amount increasing Medicare payments to doctors. His budget therefore proposes no net savings in Medicare.

In the grand bargain negotiations with Speaker Boehner last summer, the President proposed more significant incremental reforms (often mislabeled as “spending cuts”) to Medicare. Since then he has been unwilling to propose those changes publicly. Even if he did, they are far from sufficient to create a sustainable spending path.

THE PRESIDENT: Republicans in Congress want to turn Medicare into a voucher program. That means that instead of being guaranteed Medicare, seniors would get a voucher to buy insurance, but it wouldn’t keep up with costs.

A version of this horrible voucher system described by the President is now in effect for more than 100 million Americans who get their health insurance through work, and will, if President Obama is reelected, take effect soon for millions more under the Affordable Care Act. The phrase “seniors would get a voucher” is designed to maximize fear among today’s seniors, especially those who vote in Florida.

(photo credit: White House photo by Chuck Kennedy)

The President is correct that “Republicans in Congress” proposed reforming Medicare such that old-style government-run Medicare would not be an option for new Medicare enrollees in the future, but the latest version of Republican reform is the Ryan/Wyden plan, which would allow seniors to choose to stay in traditional fee-for-service Medicare. The President appears to be trying to scare today’s seniors by describing an out-of-date proposal that would have only applied to future seniors.

THE PRESIDENT: As a result, one plan would force seniors to pay an extra $6,400 a year for the same benefits they get now.

This is a great example of a tactic I warned about two weeks ago:

[me]: Every “cut program X by Y%” quote about the Ryan budget will be relative to an unsustainable spending path. The irresponsible part isn’t the proposed spending cut, it’s the promise to keep spending growth going without specifying how you’ll pay for it.

The following chestnut returns as well:

THE PRESIDENT: And it would effectively end Medicare as we know it.

Technically, to end Medicare as we know it simply means to change Medicare. Campaigning Democrats use this language, “end Medicare as we know it” to scare the listener when describing Republican proposals. To the untrained ear it sounds a lot like “end Medicare,” and the speaker uses it to mislead the listener into thinking his or her opponent proposes to eliminate this popular program. In reality, most Republicans elected officials want to end ObamaCare but only to change Medicare.

THE PRESIDENT: [Medicare is] about a promise this country made to our seniors that says if you put in a lifetime of hard work, you shouldn’t lose your home or your life savings just because you get sick… I’m willing to work with anyone to keep improving the current system, but I refuse to do anything that undermines the basic idea of Medicare as a guarantee for seniors who get sick.

This is interesting – I think it’s fairly new language for him. It provokes a few reactions.

- What about losing some of your life savings if you get sick if you’re wealthy? Given that Medicare spending is both unsustainable and a transfer of resources from younger workers to older retirees, I think it makes sense to slow Medicare spending growth in part by reducing the subsidies for future seniors who are wealthy.

- The “undermin[ing] the basic idea of Medicare as a guarantee” point ties back to the voucher attack, an attack which is now out of date because of Ryan/Wyden.

- The Medicare guarantee that the President trumpets is significantly weakened by the President’s unwillingness to explain how he intends to extend that guarantee into the future. Under current law Medicare benefits are not guaranteed for future generations because the President has not proposed and Congress has note enacted changes to Medicare that produce a reliable guarantee.

America needs to slow significantly the growth rate of government spending on the major old age entitlements. Language such as that used by President Obama may scare some seniors into voting for him, but it will make needed reforms that much more difficult after the election.

The campaign politics of the Ryan budget

Congratulations to Governor Romney for his superb choice of Rep. Paul Ryan as his VP candidate. I propose increasing the number of vice presidential debates from the one currently planned for October 11th.

The selection of Paul Ryan is about much more than just fiscal policy. Nevertheless much of the campaign politics over the next three months will be about the budget he proposed and then passed through the House. Here are a few thoughts as campaign attacks on the Ryan budget accelerate.

The fiscal politics are the inverse of the macroeconomic politics. So far the Romney campaign has framed the election as a referendum on President Obama’s economic record, while President Obama has been framing a contrast between his vision and his straw-man characterizations of the Romney/Republican vision. I expect the Obama campaign will now seek to highlight the pain in the Ryan budget while minimizing discussion of the President’s alternative budget proposal. The Romney-Ryan campaign needs to highlight the contrast with President Obama’s unsustainable proposed fiscal path.

Micro vs. macro framing – The Obama campaign and its allies will focus on micro-issues, telling horror stories of cuts to specific popular government programs. This dovetails with their constituency-based messaging so far. The Romney-Ryan campaign should try to zoom out and highlight (1) the macro effects of the unsustainable current/Obama spending path and (2) the irresponsibility of President Obama’s refusal to propose a long-term fiscal solution and his legislative party’s refusal to pass a budget. Team Obama will highlight the pain the Ryan budget would cause to targeted constituencies. Team Romney-Ryan needs to explain that the Obama budget and a failure to govern would lead to economic disaster for everyone.

Bogus spending cut numbers – Every “cut program X by Y%” quote about the Ryan budget will be relative to an unsustainable spending path. The irresponsible part isn’t the proposed spending cut, it’s the promise to keep spending growth going without specifying how you’ll pay for it. If President Obama were proposing tax increases to match his future spending growth, then this would be a fair attack. But he is not.

Incremental vs. structural change – More generally, the Obama fiscal path and campaign message rely on the false presumption that everything will be OK if we raise tax increases only on the rich and make small, mostly painless spending cuts. This is incorrect. Whether you support spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination, you need to make big, structural fiscal policy changes to get on a long-term sustainable fiscal path. Our federal government spending path is seriously out of whack and minor adjustments won’t fix it.

If you don’t want to make big “cuts” and structural changes to government spending, then the President’s current set of proposed tax increases are, at best, only a short-term fiscal band-aid. You mathematically force yourself into supporting income tax increases on the middle class and big value-added taxes. Tax increases only on the rich won’t suffice no matter how high your rates go. You are also choosing to keep raising taxes, repeatedly and forever, because the spending line slopes up while the tax line stays flat. This is an arithmetic result that is independent of my policy preferences.

It is unfair to compare a legislative end-product with an unsupported proposal. The Obama campaign will attack the specifics of the House-passed budget and attribute them all to Rep. Ryan. It is apples-and-oranges to compare the result of a House-passed budget with the President’s proposal. The House-passed budget includes compromises needed to garner the support of a majority of the House, while the Obama budget is a proposal. The Obama budget was not supported by a single Member of Congress, and the President’s party neither offered it nor an alternative in the Senate where they have a majority. Because they are the products of compromises and votes, legislative results are always messier and less intellectually coherent than any one person’s starting proposal.

Don’t forget the facts. In March I compared the deficit and debt effects of President Obama’s budget proposal with Chairman Ryan’s in both the short and long run. Here are the conclusions from those posts.

Short run comparison (10 years)

- In the short run the Ryan budget proposes lower deficits and less debt than President Obama’s budget.

- Under the Ryan budget debt would peak at 77.6% of the economy in 2014. Under the President’s budget, debt would peak at 80.4% of the economy in that same year.

- The Ryan budget would cause debt to steadily decline to 62.3% of GDP by the end of the decade. Under the Obama budget debt would flatten out by 2018 and end the decade at 76.3% of GDP, 14 percentage points higher than under the Ryan budget.

- At the end of 10 years, debt would be declining relative to the economy under the Ryan budget, while it would be flat under the President’s budget.

- For comparison the pre-crisis (1960-2007) average debt/GDP was 36.3%.

- Chairman Ryan proposes stable deficits of a bit over 1% of GDP, below the historic average deficit, followed by a gradual path to balance and eventually to surplus.

- President Obama’s budget would result in deficits that are always greater than the historic average, and that would cause debt/GDP to increase again beginning about 10 years from now.

- President Obama’s proposed deficit path is unsustainable. Our economy can tolerate high and even very high deficits for a short time. High and steadily rising deficits like those in the President’s budget cannot be sustained. Something in the economy will break.

- Chairman Ryan’s plan would result in debt/GDP steadily declining over time. It would take decades to return to a pre-crisis average.

- President Obama’s plan would result in debt/GDP stabilizing by the end of this decade, then growing steadily and forever thereafter. At some point, and no one knows when, that growing debt becomes unsustainable. If we’re lucky the resulting economic decline is gradual. If not, we have a financial crisis.

(photo credit: Romney for President site)

The policy consequences of “you didn’t build that”

I am temporarily interrupting my series of posts on lame duck scenarios to join the “you didn’t build that” discussion.

Governor Romney and his allies have been hammering President Obama for two sentences he said in Roanoke, Virginia on July 13th, colored in red below. Team Obama counters with the blue text and accuses the Romney Team of ignoring key context. I’m adding even more context than the Obama team. I think the bold text reinforces the critique of the President and, while less punchy for campaign purposes, is just as important as the red text. Here is the full text of the President’s Roanoke remarks, and here is video.

THE PRESIDENT: There are a lot of wealthy, successful Americans who agree with me — because they want to give something back. They know they didn’t — look, if you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. You didn’t get there on your own. I’m always struck by people who think, well, it must be because I was just so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than everybody else. Let me tell you something — there are a whole bunch of hardworking people out there. (Applause.)

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.

The point is, is that when we succeed, we succeed because of our individual initiative, but also because we do things together. There are some things, just like fighting fires, we don’t do on our own. I mean, imagine if everybody had their own fire service. That would be a hard way to organize fighting fires.

President Obama and his allies say Governor Romney and his allies are taking the President out of context by quoting only the sentences in red. How, then, do the President and his defenders explain the bold sentences of the first paragraph shown above? Here the President dismisses the importance of intellect and effort as contributors to success. Is there any more charitable way to interpret this text?

While in the Roanoke remarks President Obama stresses the importance of government as a contributor to the economic success of businesses, in other contexts he emphasizes the importance of luck in economic success. He frequently refers to the rich as “blessed” and “fortunate.” Here are just a few examples:

… those of us who’ve been most fortunate get to keep all our tax breaks … (source)

… we can’t reduce without asking folks like me who have been incredibly blessed to give up the tax cuts that we’ve been getting for a decade. … (source)

H.R. 9, however, is not focused on cutting taxes for small businesses, but instead would provide tax cuts to the most fortunate. (source)

I’m not going to do more if we’re not asking folks who have been most blessed by this country — like me — to just pay a little bit more in taxes, to go back to the rates that existed under Bill Clinton. (source)

In these cases and many others President Obama describes the rich as passive recipients of blessings or good fortune. He rarely credits skill, intelligence, savvy, hard work, or risk-taking as contributors to economic success. According to the President’s language, the rich are that way because they are blessed and fortunate (i.e., lucky), not because they worked harder than others, or were smarter, or savvier, or took bigger risks or sacrificed more. In this framework, success is given to you, not earned by you.

Policy consequences

The obvious conclusion that President Obama makes at Roanoke and elsewhere is that we need more government spending on infrastructure and services. Since roads and bridges, education, and basic scientific research contribute to economic growth, he argues, we therefore need more of all of them. This conclusion does not necessarily follow for several reasons.

- Government infrastructure and services are financed by taking resources from the individuals and firms that produce them. If the disincentives created by these taxes are greater than the growth benefits of increased government spending, it’s a net growth loss to the economy.

- Government infrastructure spending is often guided by politics or policy goals other than accelerating economic growth.

- Marginal government spending increases are going to increased transfers to the elderly, not growth-enhancing government investments in physical or human capital.

In addition to the spend-more-on-infrastructure conclusion, if you think that luck and/or government contribute more to success than effort, ability, sacrifice, and risk-taking, then two further important policy consequences follow.

- Incentives matter less and taxes don’t do as much damage. Raising taxes on economic success won’t undermine future success or significantly slow economic growth.

- If you didn’t earn it, you don’t really deserve it. There is a lower moral cost when government takes from the rich or from businesses, to the extent their economic success is due to luck or government.

The President’s framework supports his policy objectives. By crediting government with an important role in the success of American business, the President justifies increased government spending. By stressing luck as an important determinant of who is successful, the President reinforces his argument for higher taxes on rich individuals and successful small business owners.

“You didn’t build that,” and “You didn’t get there on your own,” and “blessed” and “fortunate” have one thing in common. They deemphasize the idea that success is earned. This makes it easier for President Obama to justify taking more from those who have succeeded.

(photo credit: Keith Park)

Lame Ducks & Fiscal Cliffs (part 2): Income tax rates

Yesterday’s introductory post to this series gave a broad overview of the fiscal policy debate, listing issues in play at the end of this year, deadlines and timeframes, and three partisan configurations that are worthy of analysis. Today we’ll begin to drill down into the income tax issues.

Income tax rate increases

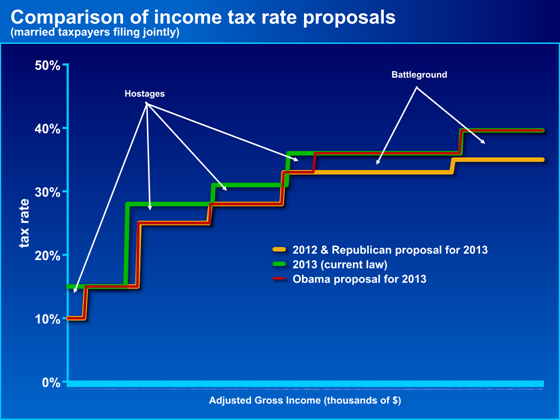

It is easiest to understand the competing proposals with a graph.

If no law is enacted this year, income tax rates will climb from the orange line to the green line. House and Senate Republican leaders propose to keep the current orange rate schedule for one additional year, through 2013. President Obama and Congressional Democratic leaders propose the red line, which matches 2012 current law and the Republican proposal for incomes up to $250K but increases those rates (or “allows them to increase as under current law,” if you prefer) to the green line for incomes above $250K.

I have labeled four regions “hostages.” These are the rate increases that both parties say they prefer not to have take effect, but claim they are wiling to allow rather than sacrifice their position on the top rates (the “battleground”). Whom you label as the hostage-taker probably depends on your preferred policy for incomes above $250K. You can see these hostages go all the way down the income scale. Especially in a weak economic recovery, threatening these hostages is both politically powerful and dangerous – like threatening a busload of nuns and puppies.

Historic recap on tax rate legislation

- The green line was in effect during the Clinton Administration.

- Then-Governor Bush campaigned in 2000 on moving rates down from the green to the orange line. The orange line was enacted in 2001 but the rate cuts were scheduled to be phased in over time. The 2001 law was the result of a bipartisan center-right legislative coalition. Because this coalition fell short of the 60 Senate votes needed to make these rates permanent, they were enacted for 10 years, through 2010.

- In 2003 President Bush proposed, and a Republican Congress enacted, a proposal to accelerate the scheduled rate cuts. This law did not change the ultimate tax rates, it just made them all take effect immediately in 2003. The 2003 law also cut dividend and capital gains tax rates. It was enacted on a nearly straight party-line vote.

- In 2008 then-Senator Obama campaigned on raising tax rates for “the rich.” In 2010 President Obama did the same. Shortly after the 2010 election President Obama flipped, seeking and enacting a deal with Congressional Republicans that extended the orange rate line for two more years in exchange for extending several policies from the 2009 stimulus law. The deals in the 2010 law expire at the end of this year.

- President Obama is once again campaigning aggressively to raise the top income tax rates, and Governor Romney is campaigning to extend (or cut) them. President Obama’s staff have threatened that the President will veto a bill that does not raise the top rates.

- In recent days and weeks, House and Senate Republicans and Senate Democrats have shortened the duration of their proposals to one-year policy changes.

Recent political history on income tax rates

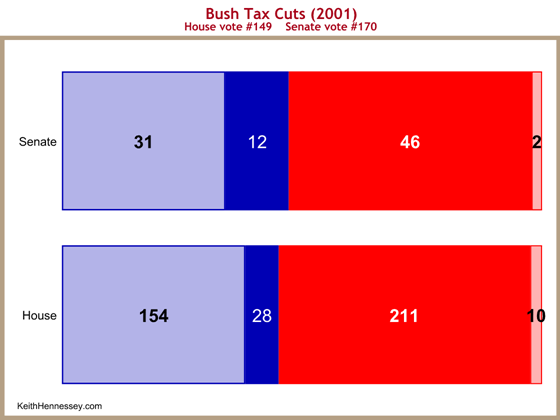

The 2001 tax law, enacted under a Republican president, Republican House, and Republican Senate, included support from a significant block of Democrats. On these graphs, Republicans are in red and Democrats in blue. Heavily shaded areas are aye votes, lightly shaded areas are no votes. Thus in the Senate, 46 Republicans and 12 Democrats voted aye on final passage, while two Republicans and 31 Democrats voted no, thus passing the bill 58-33.

This picture shows a classic center-right legislative alliance. Democratic Senators John Breaux (LA) and now-Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (MT) were the key Democrats in this effort.

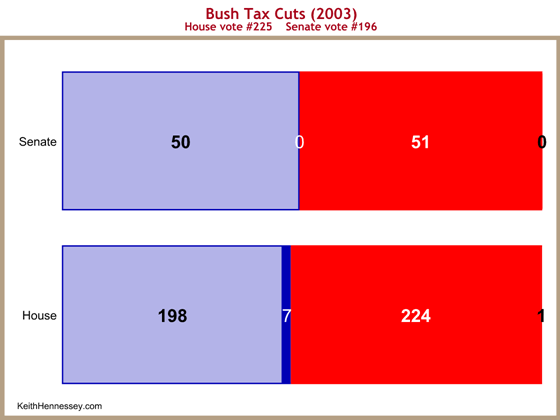

The 2003 law, in contrast, was enacted along nearly party line votes. Vice President Cheney broke the tie in a Senate split 50-50 to cast the deciding vote.

These partisan 2003 votes don’t tell the whole story. In 2003 President Bush first made the argument that the top income tax rates are the rates that apply to successful small business owners. This argument, combined with lingering support from those Democrats who had supported the 2001 law, meant that in early 2003 there was a consensus to accelerate all the income tax rate cuts, including the top rates. In 2003 there was still a bipartisan center-right coalition to keep all income tax rates low.

There was not, however, Democratic support for the other component of President Bush’s proposal, the elimination of the double taxation of dividend income. The 2003 legislative effort became a partisan fight over capital taxation, resulting in the above-displayed partisan final vote as well as today’s 15% rate for capital gains and dividend income.

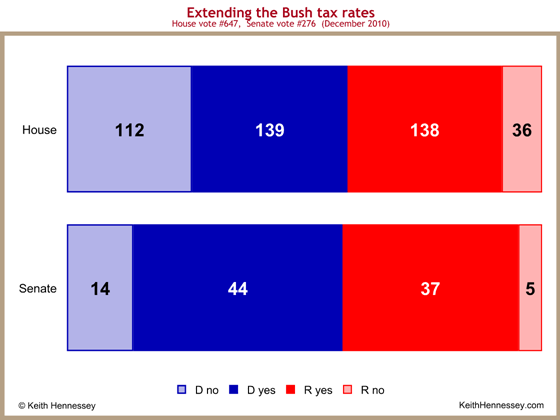

The 2010 tax rate extension law was a deal between President Obama and Republican Congressional leaders. Its vote pattern looks different from the prior two, reflecting a different balance of political forces and policy viewpoints.

This is a centrist legislative coalition. Most Republicans who voted no did so because they opposed several other things in the bill unrelated to the income tax rate extensions. Most Democrats who voted no did so because they didn’t want to extend the top income tax rates.

While in modern history Democrats have always been for higher taxes on the rich relative to Republicans, President Obama’s emphasis on raising taxes on the rich is a relatively new phenomenon. The Clinton team placed their income inequality and tax policy emphasis on the bottom of the income spectrum – specifically, welfare reform and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit. Presidents Clinton and Obama both prioritized distributional issues and taxation, but they placed their emphases at opposite ends of the income spectrum. President Clinton spent much of his legislative capital helping the poor, while President Obama is spending his trying to tax the rich.

Intraparty divisions in 2012

Republicans are more unified this year on tax rate questions than Democrats. President Obama continues to argue for rate increases on incomes above $200K (single) and $250K (married). Several Senate Democrats publicly split with the President, defining rich as incomes above $1M or saying we shouldn’t raise taxes on anyone for a year for fear of undermining an already weak economic recovery. The Senate Democrat bill now being debated sticks with the President’s income levels.

A couple of months ago House Democrats, who are usually the most liberal grouping, took a surprising caucus position that proposed tax increases for those with incomes above $1M. This was strange – to see House Democrats take a position right of the President on taxes. I’m guessing House Democratic leaders did this to prevent moderates and nervous in-cycle Democrats from splitting off and voting with Republicans.

If you look at the 2001 and 2010 votes you can see the underlying political challenge facing the President and Leaders Reid and Pelosi. Democrats often split on questions of taxing the rich. The President is siding with the liberal bloc, at least for now. Some moderate Democrats, those from high income states, and those in tough election cycles are being pressured by their party leaders to support tax increases on income thresholds lower than many of them might prefer right now. Some may also fear being portrayed as opponents of successful small businesses. President Obama and his allies in Congress have a fundamentally difficult task – holding their party together, during a tough election cycle, on a topic on which they have a history of splitting.

At the same time there is a segment of elected Republicans who would be willing to agree to some rate increase on high income taxpayers, if the thresholds are high enough (I’d guess at least $1M). But unlike their moderate Democratic counterparts, there is little political risk for these moderate Republicans to stick publicly with the party position of not raising taxes on anyone. I think this fragment of the Republican party is also smaller than its Democratic counterpart. These moderates may be a legislative challenge for party leaders during post-election negotiations, but they don’t appear to pose a major problem during this period of political positioning and campaigning.

The intraparty division among Democrats presents a tactical opportunity for Republicans. If, for instance, Senate Republicans can get a vote on raising the income thresholds in the Reid bill from $200K/$250K to something higher, they will maximize the pressure on these Democrats. If such an amendment were to pass with Democratic support it would likely raise the income floor for future lame duck tax negotiations.

Tomorrow we’ll look at the policy and political consequences of no tax deal in 2012 and at the tax negotiating landscape in a lame duck session and in early 2013. Remember that income taxes are not the whole tax picture, and taxes are only one of several important parts of the end-of-year fiscal conflict.

Lame Ducks and Fiscal Cliffs (part 1)

This is the first of a few posts on the policy decisions stacking up for the end of this year. In this post I will simply list the moving parts, deadlines and timeframes, and which election scenarios are most important to analyze. To some extent this is just a setup post for strategic analysis to follow over the next few days.

Moving parts

- taxes;

- spending, including the sequesters;

- debt limit;

- repeal of all or part of the Affordable Care Act (aka ObamaCare);

- tax reform;

- a potential Grand Bargain on fiscal policy.

The first three categories will be dealt with between now and the end of Q1 of next year. Deadlines under current law will force the Congress to make decisions on each, even if in some cases the decision is not to enact new legislation. I label these must-do parts.

The last three categories may or may not come to a head over the next eight months. Each has no fixed deadline forcing legislative action, and whether they are even priorities depends on who is elected President. I list them because they might, in some form, be included in legislation at the end of this year or the beginning of next, and because discussion about them can heavily influence the must-do items in the first three categories.

While the public tax battle is entirely about extending the top income tax rates, there are many other tax issues expiring at the end of 2012. The tax category can be further broken down into buckets of tax issues:

- extending income tax rates;

- extending capital tax rates;

- extending the President’s refundable tax credit (sometimes referred to as a payroll tax credit);

- extending estate and gift taxes;

- extending other changes from the 2001 and 2003 tax laws (e.g., child credit, education and retirement incentives);

- “patching” the Alternative Minimum Tax again;

- a collection of recurring tax extenders covering a wide range of policy areas.

The spending category also breaks down into several buckets important enough to be considered separately:

- twelve regular FY13 appropriations bills and/or a Continuing Resolution[s];

- the defense sequester;

- the nondefense sequester;

- the sequester on Medicare and other entitlements.

There are a lot of moving parts. I won’t drill down into each subpart in this series, but I want you to get a sense of how substantively complex this will be.

There is nothing magic about the way I have grouped issues. One could just as easily separate the sequester issues from other spending, or group all appropriations issues together, or combine the discussion of tax rate extensions and tax reform. For now I just want to lay out all the moving parts and propose a reasonable categorization so that it’s not all jumbled together.

Deadlines and timeframes

There are three hard deadlines and two soft deadlines that matter.

Hard deadline 1: Election day is Tuesday, November 6.

Hard deadline 2: December 31, 2012 – Taxes increase, automatic spending cuts begin to take effect. This is also the last day of the outgoing Congress, and maybe of the Senate Democratic majority.

Hard deadline 3: January 20, 2013 is Inauguration Day if Governor Romney wins. If President Obama wins this date doesn’t matter much legislatively.

Soft deadline 1: Whenever short-term Continuing Resolutions expire. Policymakers can set this date.

Soft deadline 2: At some point Treasury will run out of cash and debt management tricks and need a debt limit increase. Treasury isn’t saying when this will occur, but it’s likely between December and March.

These deadlines create a few important legislative timeframes:

- Campaign positioning window: Between now and Election Day;

- Lame duck sessions: November 7 – December 31;

- Pre-inaugural sessions: January 1 – January 19;

- 2013 really begins: January 21 and later.

Nothing big legislatively will conclude between now and Election Day. House and Senate votes in July and September are mostly attempts to influence the election and to preposition forces for lame duck session negotiations. Congress recesses in August and will spend much of October home campaigning.

The pre-inaugural timeframe is usually dead and often Congress doesn’t even meet. This makes the December 31 deadline separating the outgoing Congress from the incoming one the most important break point after Election Day.

When legislative decisions are made influences who makes them, which in turn determines the policy outcomes. I’ll go into this in more depth in a future post.

Election scenarios

There are two big scenarios to consider, plus one important variant.

- Republican sweep: Romney elected, Republicans keep the House and take the Senate majority;

- Status quo election: Obama re-elected, House stays R majority, Senate stays D majority;

- Divided government: Same as status quo except Republicans take the Senate majority.

There are plenty of other possible scenarios, the most notable of which is a Democratic sweep. I think all scenarios other than the three I listed are remote enough that I’ll ignore them. This is already more than sufficiently complicated.

Teaser

To get your gears spinning in anticipation of strategic analysis posts over the next few days, I’ll offer a few observations and questions.

- Don’t fall into the trap of thinking this is straight R-vs-D. The intraparty conflicts and tensions are at least as important.

- If President Obama loses, will he stick to his veto threat on taxes, knowing Congressional Republicans can wait him out? Or will he look for away around his veto threat and try to negotiate a deal during the lame duck so that he can extend some of his policies before he leaves?

- Same scenario — Suppose lame duck President Obama offers Speaker Boehner and Leader McConnell a good but not great deal (from their perspective) during the lame duck session. Should Congressional Republicans take the deal and lock in this bipartisan consensus, or wait for Romney to be sworn in so they can jettison the parts they don’t like? How much of a substantive sacrifice is bipartisanship worth to Congressional Republicans? To President-elect Romney?

- Who would have the upper hand in a tax stalemate in which everyone’s tax rates increase on January 1?

- The legislative dynamics on each part can be complex. What makes this analysis challenging are the interactions among the components when you start legislatively combining them. What makes it super challenging is when you realize that different people may get to make these packaging decisions during different timeframes.

More tomorrow.

(photo credit: jjjj56cp)

Senator Murray’s escape hatch

Yesterday I wrote about Senator Murray’s tax increase threat and compared it to the Tea Party / conservative Republican debt limit threat of last summer. A friend pointed out that in her threat Senator Murray left herself an escape hatch.

Here is the key sentence from the Senator’s Monday speech at Brookings (emphasis is mine).

So if we can’t get a good deal—a balanced deal that calls on the wealthy to pay their fair share—then I will absolutely continue this debate into 2013, rather than lock in a long-term deal this year that throws middle class families under the bus.

With this language Senator Murray did not rule out supporting a one or two year extension of all income tax rates, including the top rates. She only ruled out “locking in a long-term deal this year.”

Technically she could also agree to a long-term deal that extends all the tax rates, as long as it was enacted in 2013 rather than this year. She could, for instance, vote for a two month extension of all rates in December, allowing President Romney and Republican House and Senate majorities to then enact a long-term extension of all rates without her vote. I think that is a minor scenario compared with the primary flexibility she left herself to support a one or two year extension of all tax rates if President Obama is reelected.

I have no doubt that Senator Murray is serious in her desire to raise tax rates on the rich and successful small business owners. At the same time, given that she voted for the 2010 law that extended all tax rates, including the top rates, for two years, I wonder how much her current threat matters. I also wonder if her allies on the Left realize she has left herself an easy way out to support a bill they would oppose.

I still think she is using a Tea Party tactic and threatening serious economic damage if her tax increase demand is not met. Her demand, however, is less rigorous than I had originally thought.

(photo credit: un flaneur)