Under Construction

Please pardon our appearance as we adapt to a new hosting service and blogging back-end.

Thanks.

Understanding the President’s fiscal cliff offer

I am going to describe the President’s proposal to Republican Congressional leaders, then react to the most important parts of it. Secretary Geithner offered this proposal last Thursday.

This is a post for intermediate to advanced readers. Except where noted, all large numbers are for the next ten years.

President Obama’s opening bid

Items in bold are being labeled by the Administration as non-negotiable. Brackets show where I am unsure what they are proposing.

Arithmetic

This is how the Administration describes it. I think this arithmetic is absurd and explain why below.

- $4 trillion of deficit reduction relative to a current policy baseline;

- $1 trillion comes from the discretionary spending caps enacted in the Budget Control Act of 2011;

- $1 trillion comes from lowering the spending caps on Overseas Contingency Operations (aka Afghanistan and the remaining forces in Iraq);

- $400 B comes from unspecified savings in mandatory spending; and

- $1.6 T comes from tax increases.

Taxes

- Raise top two income tax rates permanently;

- Extend all other tax rates, credits, and related income tax provisions permanently;

- Tax dividend income as ordinary income;

- Estate tax: $3.6M exemption, 45% rate – These are the parameters that were in place in 2009.

- Capital gains rate increases to 20%;

- Extend the Payroll tax credit;

- Extend bonus depreciation for business investment;

- Permanently extend the Alternative Minimum Tax;

- Permanently extend a package of routinely expiring tax provisions, mostly for businesses, known colloquially as tax extenders.

Debt limit

<

ul>

Spending

- $50 B additional highway spending in 2013 above baseline, with five years after that of $25 B more per year (total of +$175 B over six years);

- Permanently extend Medicare payments to doctors (aka the Sustainable Growth Rate, aka a permanent doc fix);

- Extend Unemployment Insurance [for how long? a year?];

- the Menendez/Boxer housing refinance bill;

- Delay the entire 2013 sequester and find $109 B of unspecified savings to cover the deficit effect of the delay;

- [Propose? Support? Enact?] Tax reform in 2013 that increases taxes on the upper brackets by $600 B by capping deductions;

- [Propose? Support? Enact?] Entitlement reforms in 2013 that cut spending by $290 B;

- The 2014 sequester would [somehow] be used as an enforcement mechanism to drive tax reform and entitlement reform in 2013.

Analysis

Arithmetic

The President’s arithmetic is absurd. The BCA cap reductions were enacted 16 months ago, but Team Obama wants to count that $1 trillion again as if it is future deficit reduction. The Afghanistan OCO caps are mythical savings—the President never proposed to spend those funds, but they want to count savings by not spending them.

The $1.6 trillion in tax increases would be real if enacted. There are no budgetary or arithmetic games here, just policies I strongly oppose.

They specify no details on their $400 B in mandatory spending cuts. All entitlement programs, including the big four (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and ObamaCare) are mandatory spending, as are farm subsidies, student loans, welfare payments, and a bunch of other things. But certain “offsetting receipts” also technically count as mandatory savings, even though to you and me they look much more like increased fees or asset sales (like auctioning off telecommunications spectrum). The $400 B figure is therefore, at best, a ceiling for gross spending cuts. And of course the President and Congressional Democrats keep reminding us that they won’t touch Social Security and really don’t want to cut Medicare, Medicaid, or ObamaCare.

Also, note that the President’s proposal would enact only $109 B of mandatory savings now. The other $290 B might come in 2013 as a result of entitlement reform.

I’m sure someone will ask what the total effects of the President’s proposal are on spending, taxes, and deficits. That’s a simple question with a really complex answer, and I’m not going to try to answer it today. If you’re a reporter and need to know, I’d go to Chairman Ryan’s and Chairman Sessions’ staff. Don’t try to calculate it yourself. I estimate below that the net effect of his spending proposals, however, is to increase rather than cut spending.

“Balance”

Team Obama makes a big deal about balancing spending cuts and tax increases.

They measure spending cuts starting from current all-time historically high spending levels, and they measure tax increases from revenue levels which are artificially low because of the weak economy. This skews even an honest measurement of spending cuts and tax increases in favor of those who prefer higher taxes. It also means that any calculation of a ratio between spending cuts and tax increases is fundamentally misleading.

If that weren’t bad enough, Team Obama continues to try to combine previously enacted spending cuts with proposed future tax increases, and to treat them as if they were part of a package of future policy changes. I don’t use this term lightly: this is a lie. The President’s version of balance means “In 2011 we enacted a bunch of spending cuts, so now to balance it we’re going to rely almost entirely on tax increases.”

I expect Obama spokesman to claim they have more spending cuts than tax increases. They’ll add the $2 trillion of past (BCA) and mythical (OCO) spending cuts to the $400 B of spending cuts, three-fourths of which they don’t want enacted in this bill, and say that the total is more than the $1.6 T of tax increases the President demands be enacted now. That would be funny if it weren’t so dangerous.

I saved the best for last. The President is proposing spending increases, not spending cuts. He claims $400 B of spending cuts for policies he hasn’t specified, and $291 B of which wouldn’t be considered until next year. But he proposes to spend $109 B to delay the sequester for a year (GOP defense hawks will like this), and another $175 B on highways, and another $30ish B on unemployment insurance. Then he’s got the cost of Menendez-Boxer on housing (I don’t know), and the cost of a permanent Medicare doc fix (hundreds of billions, depending on the details). The net result of his proposal is higher spending, not lower.

Taxes

I’ll start with something positive. Good for them for proposing a permanent AMT patch.

Note that they say “raise the top two income tax rates.” They don’t say “raise them to pre-Bush rates, with a top rate at 39.6%.” Team Obama has been fairly clear in signaling that they insist that rates go up on “the rich,” but they’re flexible on how much of a rate increase they’ll support. Their $1.6T total assumes these rates go all the way back up.

I understand that Team Obama says the rate increases, dividend policy, and estate tax are non-negotiable. Obviously we know that’s not true because they have flexibility on how much the rates would increase, but that’s what they’re saying.

The President proposes to tax dividend income as ordinary income. The President is, I believe left of some Senate Democrats on this question. They left this policy change out of their version of a bill earlier this year.

The same is true on the estate tax. The President says his estate tax proposal ($3.5 M exemption, 45% rate) is non-negotiable, yet the Democratic Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee wants a higher exemption and a lower rate, causing Senate Democrats to leave the President’s estate tax proposal out of their alternative bill earlier this year.

Extending the payroll tax credit is a bargaining chip for the President. I have no doubt he’d trade it away.

Someone needs to explain to me why Congressional Republicans would agree to make “the rich” pay $1.6 T higher taxes to avoid a $1 T tax increase on them if there is no law. The practical ceiling for tax increases on “the rich” in these negotiations seems to be just shy of $1 T. Team Obama threw the other $600 B in just to frame $1 T later as a huge concession on their part. It’s not and it won’t be when they make this move.

Debt limit

I understand the “no more debt limit votes after this one” provision is being labeled by the Administration as non-negotiable. If that holds, it could by itself be a deal-breaker.

Members of Congress hate voting to increase the debt limit, so some may be tempted by the President’s proposal to do away with it. But neither the President nor his party seem willing to address entitlement spending trends unless forced to do so. Senator Reid refuses to pass budget resolutions, and the President appears to have forgotten about his prior statements of wanting to slow entitlement spending growth. Republicans therefore need to insist on short-term debt limit increases to create repeated deadlines to force spending issues to be considered. Yes, this is messy and undesirable, but if the President and Leader Reid would do their job it would not be necessary.

I recommend leaving a debt limit increase out of this bill, to force a separate negotiation on entitlement spending in Q1 of next year. Future debt limit increases should be of no more than one year each until the Senate starts passing budgets.

Bob Woodward’s book describing the summer 2011 negotiations showed a President whose top priority was getting a debt limit increase big enough to avoid any further fiscal deadlines until after the election. If accurate, that suggests that the President’s new goal might be to get a new debt limit increase to last beyond 2016 so he can get all this fiscal stuff behind him and not be bothered by it.

Spending

Nothing like a cool $175 B more highway spending to start the new year, is there? This is trade bait, but Team Obama also knows that Rs are always tempted by more money for roads. Note that he didn’t ask for more money for rail or mass transit, or green energy to make it more attractive to Republican spenders.

It appears the President doesn’t want to offset the massive cost of a permanent “doc fix.” That’s really, really expensive, and it further worsens our Medicare spending problem.

I don’t know enough about the Menendez/Boxer housing bill, but I’ll bet the President would give it up to get a deal.

In this proposal the proposed $1.6 trillion in specific tax increases, hundreds of billions of dollars in detailed spending increases, and zero in specific spending cuts.

Future promises

Follow this logic.

In the summer of 2011, President Obama and Speaker Boehner failed to negotiate a Grand Bargain, so they enacted a law which created a Super Committee of Congress to find $1.2 – $1.5 T of spending cuts. In case the Super Committee failed, that law, the Budget Control Act of 2011, created a backup set of sort-of-across-the-board spending cuts to hit the same $1.2 T spending cut target.

The Super Committee failed, so the spending sequester is scheduled to begin one month from now.

The President, most Democrats and many Republicans in Congress want to reduce or delay the sequester.

The President proposes a one-year delay, which would increase the deficit by $109 B in 2013. He wants to enact (in December) mandatory savings of an equal amount, but he proposes no specifics.

In this offer he promises Republicans that the tax reform and entitlement reform that they so desire will be backed up by the threat of, wait for it, the sequester that will begin in early 2014.

See anything wrong with this logic?

Why should anyone believe that a sequester being delayed now will serve as a useful forcing mechanism to drive legislation in 2013 on Republicans’ top two fiscal priorities?

Senate Minority Leader McConnell was right to laugh at the President’s proposal, and Speaker Boehner was right to call it “silliness.”

This is not a serious offer.

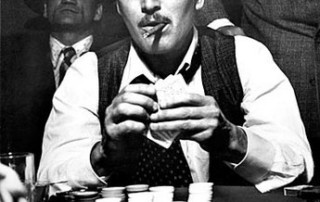

(photo credit: Paul Couture)

WSJ op-ed: Time to Call the President’s Budget Bluff

The Wall Street Journal has published an op-ed of mine, titled Time to Call the President’s Budget Bluff.

More on the President’s veto bluff

Yesterday I argued that the President is bluffing on his veto threat. Today I want to respond to some great feedback from friends and readers. Warning: discussions of negotiating strategy and tactics can get a little dense.

1. I agree that Senate Democrats would likely block any bill that the President would veto. This means the veto threat is important principally to reinforce Leader Reid’s efforts to hold his Democrats together as a unified bloc.

But if I’m right that the President thinks he cannot afford to risk a recession, then the President needs a new law. Whether a bill dies in the Senate or as a result of his veto, in either case no law –> fiscal cliff –> recession –> severe damage to the rest of the President’s agenda. My hypothesis is that the President is unwilling to take that risk, so he needs the House and Senate to pass a bill he can sign. I think my argument holds whether the veto would be actual or merely a tool to reinforce his allies stopping a bill in the Senate.

2. I agree that, were it not for the recession risk, many Democrats, possibly including the President, would think that no new law was a good fiscal policy outcome. Yes, the President and almost all Congressional Democrats say they want to extend current tax rates for the non-rich. But if all tax rates go up, future deficits will be $5.4 trillion lower. If the sequester is allowed to bind, deficits would be reduced by another $1.2 trillion over the next decade. This outcome, of no new law, would give the President a lot more fiscal flexibility. The deficit and debt problem would be far from solved, but he would have more room to propose new spending that I’m guessing he wants.

There’s an interesting intra-Democratic party tension here. Which is more important to elected Democrats: preventing middle class tax increases or having more room to increase government spending? The President insists he wants to prevent tax increases on the middle class, but it’s easy to believe that he, and especially some Congressional Democrats, would be happy to have such broad-based tax increases to finance their desires to expand government.

If you think the President thinks the potentially quite significant fiscal policy benefits (from his point of view) of no deal are greater than the costs of a 2013 recession and the damage it would do to his entire policy agenda, then you disagree with me and should conclude the President is not bluffing.

- There are clearly some important Congressional Democrats (e.g., Senator Patty Murray) who appear willing to risk a recession so they can have more money to spend. I disagree with those who suggest those Congressional Democrats would block a bill that the President wanted to sign. If he wants a deal, he’ll be able to deliver the Democratic votes to pass it, and if he wants a bill blocked, they’ll block it for him.

Indeed, the President’s greatest tactical weakness is the varying views within the Democratic party, and especially differences between confident liberals like Senator Murray and nervous in-cycle moderates. Congressional Republicans need to figure out how to expose and exploit these differences and split Congressional Democrats. I will address that in a future post.

5. One wise friend thinks the President is so confident that he would win an early 2013 blame game that he is willing to risk a recession.

In this view you agree that the President still wants and needs a new law to avoid a recession. You also think that not only does the President think he has negotiating leverage now, he thinks his leverage would increase after the new year if there is no new law. You would argue that he is willing to gamble that, faced with the prospect of being blamed both for tax increases and triggering a recession, Republicans would quickly fold in January 2013 if there is no deal. Therefore, you think he thinks risking a recession still won’t result in a recession, because it will end quickly when Republicans cave.

Thanks to all who provided great feedback and counterarguments. For now I’m going to stick with my original view. I think the President thinks he needs to get a deal because I think his highest priority is (and should be) avoiding even the risk of triggering a new recession in the first year of his second term.

What scares me more is that I fear the President wants a deal but doesn’t know how to get one with Republicans. My working hypothesis is that the President is an ineffective negotiator when dealing with those who disagree with him. This view is heavily reinforced by Bob Woodward’s book The Price of Politics. Other than two years ago when he swallowed the Republican view whole and extended all tax rates, the President is oh-for-Administration in major bipartisan legislation. At the moment I worry less about the President’s goals and priorities, and more about his negotiating skill and his capacity to reach agreement with those with whom he strongly disagrees.

(photo credit: Jim Moran)

The President is bluffing

I think the President is bluffing on his veto threat.

Conventional wisdom: To achieve his desired fiscal policy outcome (big tax rate increases on the rich), the President is willing to risk tax increases on all income tax filers. He is also willing to risk the political blame for middle class Americans paying higher taxes because he thinks he can shift most of the political blame onto Republicans. He is therefore willing to veto a bill he doesn’t like and bear the consequences of having no bill, if that’s what is needed to gain negotiating leverage. His veto threat is credible.

This conventional wisdom makes three key assumptions.

- The President’s top economic policy priority is his fiscalpolicy goal (raising taxes on the rich).

- In a veto / no bill / blame game scenario, the President can shift most of the political blame to Republicans.

- He will make his veto decision on these two bases: fiscal policy and relative political blame.

Key flaw in the conventional wisdom: The President’s veto decision is not about tax increases or political blame; it’s about causing a recession in 2013.

I make different assumptions.

- If there is no bill, the U.S. economy will probably dip into recession for much/most/all of 2013, and it’s impossible to predict whether such a recession would be short-lived.

- A 2013 recession would be terrible for the country and terrible for the Obama Presidency. It would limit the President’s options across his entire policy agenda, economic and non-economic. And it could define and dominate his entire second term.

- President Obama believes #1 and #2, and therefore avoiding the risk of triggering a recession with his veto is an even higher policy priority than his fiscal policy goal.

- The President wants to get things done. He cares more about his own chances for policy success (across the entire breadth of his agenda, whenever he figures out what it is) than he cares about relative political blame. A scenario in which Republicans get most of the blame for a veto-triggered recession is still a loser for him if it means he can’t accomplish his second term goals.

If my assumptions are correct, then the President cannot afford to veto a bill and have no compromise enacted. Even if doing so increases dramatically the chance of getting his top fiscal policy priority, and even if he would bear only a small portion of the political blame for a legislative failure and the pain of broad-based tax increases, his veto would trigger a recession that would severely damage his agenda at least in 2013.

President Obama’s veto threat decision is not just about fiscal policy, and it’s not just about who gets blamed for a legislative failure. It’s about whether the President wants to cause a recession in 2013 and hamstring his second term. No matter what he or his advisors say, he cannot afford to take that risk.

(photo credit: Kaptain Kobold)

Reactions to the President’s press conference

I have three quick reactions to today’s Presidential press conference.

1. The President upped his demands today. He had been previously been demanding that income tax rates increase on “the rich.” Treasury says that doing so would raise $442 B of revenues over the next decade. Today the President said that “extending further a tax cut for folks who don’t need it, … would cost close to a trillion dollars.” That means his opening bid is assuming much more than just increasing the top two rates.

Using Treasury numbers, one could get to just shy of a trillion dollars by including the following Presidential proposals to “sunset tax cuts” that would affect “the rich” (in all cases, incomes > $200K for single filers, and > $250K for married filers):

- Increase the top two income tax rates;

- Phase out the personal exemption for upper-income taxpayers (aka “PEP”);

- Limit itemized deductions for the rich (aka “Pease”);

- Tax capital gains at 20% (the pre-2001 rates);

- Tax dividends as ordinary income (the pre-2003 policy); and

- Raise estate and gift taxes to 2009 levels.

We may not, however, be able to stop at $1 trillion. I am told that in other contexts the President’s team (including Acting OMB Director Jeff Zients in public remarks today), are saying the President’s opening bid is not $1 trillion, but $1.5 trillion of new revenues, raised entirely on the individual side. I am trying to confirm this, and I wish someone would ask Jay Carney what the President’s revenue number is for lame duck / fiscal cliff negotiations. In his press conference, the President used $1 trillion to describe one possible policy outcome, rather than as a description of his negotiating position. That is at least consistent with a higher $1.5 trillion number.

2. Over the past five days the President and his team have not insisted that tax “rates” go up, but instead that tax “cuts” for the rich not be extended. Like many others I had at first been interpreting that as a sign of potential flexibility, that he might be open to Speaker Boehner’s idea of raising taxes on the rich by limiting or eliminating their tax preferences. I now have a different view, shaped principally by a new understanding of the size of the tax increase the President is requesting.

I think the Administration wants to raise a lot of revenue ($1T – $1.5T), and they know that it is infeasible to raise that much without raising tax rates.

I now think the ambiguity, the choice not to use the word “rates,” was not to allow for negotiating flexibility but instead to allow flexibility to demand more than just rate increases on the rich. By using “tax cuts” rather than “tax rates,” they can make their total opening bid $1 or even $1.5 trillion.

This is a significantly more pessimistic interpretation of the same language than I had previously, and it’s more pessimistic than most other observers. If I’m right, not using “rates” is part of a strategy to set an absurdly high opening bid, one so high that makes it harder to close a deal during the lame duck session.

- It seems like the President is thinking about the threat of tax increases (aka “going over the fiscal cliff”) in relative negotiating terms, and not as much in absolute policy terms. That is, his language suggests that he thinks no legislative deal would be worse policy and worse politically for Republicans than it would be for him. If he’s right, then that should give him leverage in the negotiations, because Republicans should be willing to “pay more” to avoid that stalemate outcome.

The problem is that he has a responsibility to think about a stalemate not just in relative terms (and especially not just in relative political/blame terms), but also as a matter of absolute policy. No matter who gets blamed for it, a legislative stalemate leads to a terrible short-term macroeconomic consequence: increased unemployment and a new recession, says the Congressional Budget Office. The President’s public posture treats this as if it’s not a big deal because it’s worse for Republicans. Far more importantly, it would be a terrible outcome for the country.

(White House photo by Pete Souza)

The President sends mixed signals on the fiscal cliff

President Obama is sending mixed signals on the fiscal cliff. Here is how I interpreted the President’s statement last Friday (emphasis added today).

I think the most positive thing that can be said about the President’s statement today is that he didn’t say anything that clearly made a deal more difficult. With one important exception, he didn’t budge on substance …

… The one important exception is that today the president did not insist on raising tax rates on the rich, only that they “pay more in taxes.” I assume this was intentional. It allows for at least a portion of the deal like that suggested by the Speaker’s comments: scale back tax preferences for the rich without raising their marginal rates. Of course, that’s only part of what the Speaker said was necessary, but it’s a critical part.

My interpretation was far from unique. Several other observers drew similar conclusions from the President’s apparent constructive ambiguity. It appeared the President was, in reaction to Speaker Boehner, leaving the door open to a deal that raised taxes on the rich but did not raise their tax rates.

But later that same day the President’s press secretary Jay Carney reiterated the President’s prior veto threat:

MR. CARNEY: The President would veto, as he has said and I and others have said for quite some time, any bill that extends the Bush-era tax cuts for the top 2 percent of wage earners in this country, of earners in this country.

I think that means the President would veto a bill unless the top rates go up. He is not requiring that they increase to pre-Bush levels (i.e., not requiring that the top rate increase from 35% to 39.6%), but he is requiring that the 35% number increase, since otherwise the bill would be “extend

My interpretation of the President’s apparent implicit flexibility is inconsistent with Mr. Carney’s explicit statement. There are a few possible explanations.

- Intentional Presidential head fake – Mr. Carney’s reiterated veto threat accurately represents the President’s position. The President’s apparent constructive ambiguity was a head fake. While it is consistent with the Boehner offer, it is also consistent with no change in the Presidential position. Leaving “higher rates” out of the President’s Friday statement was a head fake to make him seem constructive without giving any ground. In this explanation we should treat the reiterated veto threat as binding (at least for now), and I was too optimistic in my interpretation of the President.

- Intentional mixed signals to play for time – By setting up the President as the good cop and Mr. Carney as the bad cop, they can point to the two conflicting statements depending on the audience. Liberal audiences are reassured by the reiterated veto threat, while reporters are directed to the President’s more open statement that makes him look flexible. They can then choose later which statement to make the “real” one.

- Unintentional Presidential head fake – This is the same as #1, but the head fake was an accident. They didn’t intentionally leave out “rates” from the President’s statement, and observers (including me) jumped to a mistaken conclusion.

- Mr. Carney didn’t get the memo – The President is open to the Speaker’s suggestion and intended to signal this in his Friday remarks. Mr. Carney failed to update his talking points to be consistent with the President’s new posture. In this scenario we should ignore the veto threat, or Team Obama may look for an opportunity to “walk the threat back” in one of their many public events on this topic this week.

I hope Speaker Boehner and Congressional Republicans take advantage of Team Obama’s ambiguity and try to move an agreement forward. If asked about the Carney veto threat, a Republican should reply, “When they conflict, I take the President’s words as trumping what his staff says. The President sounded like he was leaving the door open to a solution like that suggested by the Speaker. I will remain hopeful of progress unless I hear the President change his language.” Congressional Republicans should ignore the veto threat for now.

We know that President Obama relishes public fights about tax distribution; he made this issue an important one in his campaign. We don’t yet know whether he is as effective at finding common ground with Republicans as he is at fighting with them.

The fiscal cliff is a test of President Obama’s ability to negotiate with people with whom he disagrees. He was unsuccessful in this regard in his first term. If he fails again over the next seven weeks, American taxpayers and workers will suffer for it.

(photo credit: Tom Magliery)

Fiscal cliff diving

It has been more than a month since I last posted. With statements Wednesday by Speaker Boehner and today by President Obama about the upcoming “fiscal cliff,” this seems as good a time as any to dive back in. This initial post will assume a fairly high amount of baseline knowledge. I may return to the basics in later posts (as I said I would do a while back).

I will describe and interpret both leaders’ statements, then offer a little analysis of the two positions together. I need to emphasize that at this early stage, anyone’s interpretations and predictions are highly speculative. I am doing little more than making educated guesses; then again, so is everyone else.

Both leaders deserve credit for making serious and fairly detailed policy speeches. Both are contributing significantly to the public debate by laying out their views and arguments for all to see. Public policy would be sufficiently improved if we had more serious public discussion like this.

Speaker Boehner’s statement

Speaker Boehner opened that public discussion on Wednesday.

- He frames the election result, in which President Obama and a House Republican majority were both reelected, as “a mandate for us to find a way to work together,” not “to compromise on our principles,” but instead “to creating an atmosphere where we can see common ground when it exists, and seize it.” His general tone is cooperative.

- He leans heavily against trying for Grand Bargain II during the lame duck session. He probably thinks (correctly) that it’s infeasible. Based on earlier press reports, he may also think it’s inappropriate to make such large policy changes with a bunch of retiring members. Better to wait for the new Congress and take the time to do it right.

- Here is his key language for the next two months:

What we can do is avert the cliff in a manner that serves as a down payment on – and a catalyst for – major solutions, enacted in 2013, that begin to solve the problem.

- As a policy matter he criticizes temporary policy changes. As a practical legislative matter, he suggests a short-term trade (which I’ll describe in a moment) to buy up to a year to legislate a big fiscal solution.

- For that bigger solution he is explicit about being willing to agree to more total government revenues, but only under a few conditions:

- Those revenues should come as part of base-broadening tax reform that produces faster economic growth;

- That tax reform should lower marginal tax rates;

- This should “mak[e] real changes to the financial structure of entitlement programs, and reforming our tax code to curb special-interest loopholes and deductions.”

- He explicitly links higher revenues to entitlement reform that cuts spending: “[T]o garner R support for new revenues, the president must be willing to reduce spending and shore up the entitlement programs that are the primary drivers of our debt”

- I can’t find an explicit indication that the Speaker is willing to have higher taxes on “the rich” (however one defines that), but I think it’s implied. It was certainly true in the Portman/Toomey offer in the SuperCommittee last fall. More on this in a bit.

- Finally, he says “the President must lead.”

Here’s my summary of the Boehner formula:

Boehner: tax reform that lowers marginal rates + real changes to the financial structure of entitlement programs ==> faster economic growth + higher revenues + lower deficits + higher average tax burden on “the rich”

If I am interpreting him correctly, the key trade implied by Speaker Boehner is that Republicans would agree to higher average tax rates paid by the rich, but not higher marginal tax rates. The rich would therefore pay higher taxes, but the tax on their last dollar of income would not go up. Thus more revenue would be raised from them, and they would be paying more in taxes, but their incentive to work and invest more at the margin would not be dulled. The Speaker conveys this by distinguishing between “revenues” and “tax rates.”

Some in the press have reported this as a new policy position for the Speaker. While it’s more directly stated and blunt, I’m not seeing any significant change from his position in the summer 2011 Grand Bargain negotiations with the President. My simple version is that the Speaker is taking his then-private (but well-known) position public, and suggesting an open legislative process instead of private one-on-one negotiations. Any reporter who frames this as a big policy change hasn’t been paying close attention. Despite everything you’ve read, the bright line that Republicans purportedly drew on taxes was always somewhat blurry.

It is, however, unclear to me what the Speaker means by a down payment to be enacted in the lame duck session. My best guess is that it might involve some modest entitlement reforms, plus scaling back some tax preferences for high-income tax filers, plus an extension of all current (2012) rates. If I’m guessing right, the short-term deal would include higher average taxes for the rich but no increases in their tax rates. I think the Speaker’s long-term framework would require their marginal tax rates to decline as a part of tax reform, rather than just not increase. I emphasize that here I’m really just guessing.

The President’s statement

OK, let’s do the same with the President’s statement today.

- “Confrontational” is too strong to describe the President’s language and tone. “Insistent” is probably better. It’s not surprising that the President insists the election gave him a mandate to implement his fiscal policies. Key quote:

On Tuesday night we find that the majority of Americans agree with my approach. That’s how you reduce the deficit … with a balanced approach. … So our job now is to get a majority in Congress to reflect the will of the American people.

- Like Speaker Boehner, the President is reiterating his earlier substantive position. He wants to extend all income tax rates except for those with incomes greater than $200K/$250K. He wants those rates “for the rich” to be allowed to increase on January 1 as they will if there is no new law.

- The President praises the Senate for passing a bill that matches his policy of raising tax rates for incomes > $250K, and he says the House should pass that bill and he would sign it. But aside from this statement, he does not insist that tax rates on the rich pay more.

- He also reiterates major elements of his budget: spending increases on education, infrastructure, clean energy, and veterans, along with (a claimed) “$4 trillion of deficit reduction over the next decade.”

- Interestingly, he does not frame the choice as “raise taxes on the rich to reduce the deficit.” He instead frames it as “raise taxes on the rich and cut spending to reduce the deficit and make needed investments (i.e., government spending increases).”

- Once again his key word is that any deficit reduction package must be “balanced.” By this he means that it must raise taxes on the rich.

- He hits hard, a couple of times, that the short-term solution should be the common denominator – Congress should extend the tax rates except those for the rich. The top tax rates, he suggests, can then be negotiated as part of a broader fiscal deal next year.

- He also says

I was encouraged to hear Speaker Boehner agree that tax revenue has to be part of the equation, so I look forward to hearing his ideas when I see him next week.

Here’s my summary of the Obama formula:

Obama: higher taxes on the rich + spending cuts + spending increases ==> faster economic growth + higher revenues from the rich

It appears that President Obama also has low expectations for a Grand Bargain II during the lame duck session. I think the most positive thing that can be said about the President’s statement today is that he didn’t say anything that clearly made a deal more difficult. With one important exception, he didn’t budge on substance or even frame his prior positions in a more conciliatory or cooperative manner. That shouldn’t be too surprising in an opening framing statement for negotiations, but it’s a pretty sharp contrast with the Speaker’s statement yesterday.

The one important exception is that today the president did not insist on raising tax rates on the rich, only that they “pay more in taxes.” I assume this was intentional. It allows for at least a portion of the deal like that suggested by the Speaker’s comments: scale back tax preferences for the rich without raising their marginal rates. Of course, that’s only part of what the Speaker said was necessary, but it’s a critical part.

Analysis

Let’s compare the two formulas:

Boehner: tax reform that lowers marginal rates + real changes to the financial structure of entitlement programs ==> faster economic growth + higher revenues + lower deficits + higher average tax burden on “the rich”

Obama: higher taxes on the rich + spending cuts + spending increases ==> faster economic growth + higher revenues from the rich

Both formulas are incomplete so far, in that neither covers the sequester or the debt limit. The sequester kicks in January 1 if the law isn’t changed. The debt limit is on a slightly slower timeline.

Initial press coverage focuses on the possibility of a deal on taxes on the rich. As you can see, there are a lot of moving parts left to resolve even if they do work out that biggest difference.

The key conclusions I draw about this week are:

- A Grand Bargain II in the lame duck session is highly unlikely.

- Both sides appear willing to continue that negotiation next year, maybe through the traditional legislative process rather than in private.

- A middle ground on one issue could involve higher average tax rates for the rich with no increase, or even a cut in their marginal rates. This could be accomplished by scaling back tax preferences for high income tax filers.

- The Speaker needs to do this, substantively and politically within his conference, through tax reform.

- Both sides appear willing to discuss entitlement spending changes. The Speaker is once again more aggressive on these than the President, and the Speaker insists that any revenue increases must be accompanied by entitlement spending changes (often mislabeled as “cuts”).

Q: OK, but that’s next year. What about now? What’s going to happen between now and the new year?

A: I have no idea. Neither does anyone else, including the participants. A smaller version of that deal is, in theory, possible during the lame duck session: incremental changes to the major entitlements plus scaling back tax preferences for the rich, and keeping all the rates in place for, say, a year. This could fit the Speaker’s idea of a “down payment on reform,” and could meet the President’s test of having the rich pay more, without crossing the Speaker’s bright line of not raising anyone’s rates. There are a lot of moving parts in that deal. It’s possible to do such a deal if both sides are skilled and constructive negotiators. Those are big IFs.

I apologize for the complexity of this post—there are a lot of moving parts, and I’m doing the best I can to clarify things. Even if I’m a bit lucky and right on all of this, my answer is still incomplete because it leaves the short-term sequester questions unanswered. I am afraid at this point it’s the best I can do. I will try to improve my analysis as we move forward.

(photo credit: Sam Effron)

For tonight’s debate

Here’s the question I’d like to see Jim Lehrer ask President Obama:

President Obama, you and Speaker Boehner were unable to reach a big picture budget agreement last year. If you are re-elected and Mr. Boehner continues as Speaker, why should voters expect a different result over the next four years? Why shouldn’t Americans expect the budget stalemate just continue?

Separate but related, at some point I assume President Obama will say he inherited our current deficit problems. This is a little long, but it would be great to see Governor Romney respond like this:

Mr. President, for almost four years you have been telling us that you inherited huge fiscal problems, and you have told us that the past four years of trillion dollar deficits aren’t your fault. Why have you spent so much time complaining about who is to blame for our Nation’s deficit and spending problems and so little time solving them?

The budget you propose would accumulate another $6 trillion of debt over the next decade. The long-term budget problems are even more severe, and you still haven’t proposed a solution to them. Presidents are supposed to lead, and you have not.

Yes, we know that you want to raise taxes on the rich. You think the problem is that government doesn’t have enough money, so you propose tax increases. But if we did what you propose we’d eliminate only one-twelfth of next year’s deficit, and only one-sixth of our deficit ten years from now. I think the problem is that government is spending too much, and the obvious solution is to reduce the size of government.

If I am elected President, I will make reducing deficits and cutting government spending top priorities. I will propose a budget that solves our short-term and long-term deficit and government spending problems, and I will take all the energy that you have devoted to blaming someone else, and instead dedicate it to working with anyone, of either party, who will work me to solve the problem. I have already proposed several specific ideas, including changes to the major entitlement programs that drive our fiscal problems.

It is time to stop worrying about who gets blamed when things go wrong and start working on getting economic policy right.

(photo credit: Randy Slavey)

The Washington Post’s hatchet job on Paul Ryan

Today’s Washington Post contains an election-season hatchet job on Paul Ryan by reporter Lori Montgomery, “Amid debt crisis, Paul Ryan sat on the sidelines.” I would expect a story like this on the Newsweek or Huffington Post sites, but the Post purports to be nonpartisan and balanced.

Ms. Montgomery’s story offers two premises:

- Mr. Ryan “sat on the sidelines” rather than act, and in doing so he failed to behave as a responsible legislator;

- He would rather espouse conservative principles than engage in the messy business of bipartisan compromise.

Here is Ms. Montgomery’s core assertion:

But knowledge is not action. Over the past two years, as others labored to bring Democrats and Republicans together to tackle the nation’s $16 trillion debt, Ryan sat on the sidelines, glumly predicting their efforts were doomed to fail because they strayed too far from his own low-tax, small-government vision.

Here is her evidence:

- Ryan voted against the Bowles-Simpson recommendations;

- Through much of 2011, he insisted publicly that a “grand bargain” on the budget was impossible; and

- He “asked Boehner not to name him to the congressional ‘supercommittee’ that took a final stab at bipartisan compromise last fall.”

- He voted against a measure to dial back unemployment benefits and extend a temporary payroll tax holiday.

Not mentioned

She writes that Mr. Ryan “did draft a blueprint for wiping out deficits by 2040,” but she fails to mention that he passed that plan through the House. She does not report that Mr. Ryan’s staff were providing behind-the-scenes technical assistance to Speaker Boehner during the Grand Bargain negotiation. She doesn’t report that Mr. Ryan loaned his budget committee staff director to Mr. Hensarling on the super committee. She doesn’t mention that Mr. Ryan’s prediction that the super committee would fail came true, or that the Obama White House was AWOL during the super committee negotiations. She doesn’t mention that he voted for the Budget Control At of 2011, for the tax rate extensions at the end of 2010, and for the FY 2012 Omnibus Appropriations Act, three major bipartisan fiscal laws that deeply split House Republicans.

Action

Did Chairman Ryan sit on the sidelines over the past two years? On April 15, 2011, the House passed the FY 2012 budget resolution. On March 29, 2012, the House passed the FY 2013 budget resolution. Both were written by Mr. Ryan, passed by him out of his Budget Committee, and he managed the floor debate for each.

It is true that Mr. Ryan never reached a bipartisan conference agreement on either of his two budget resolutions, but that’s because the Senate never did its work. Mr. Ryan’s Senate counterpart, Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D), did not pass a Senate budget resolution for any of the last three years. It is unfair to criticize Mr. Ryan for failing to reach a bipartisan compromise when his Democratic counterpart didn’t even show up or do his job.

More importantly, Mr. Ryan acted. His job as Budget Committee Chairman is to pass a budget resolution, and he did his job both years. Ms. Montgomery criticizes Mr. Ryan for failing to cut bipartisan deals in ad hoc negotiating forums. Yet he was not a member of two of the three, and she fails to give him credit for doing his job by passing legislation. As Budget Committee Chairman Mr. Ryan produced more concrete legislative progress than the Bowles-Simpson Commission and the super committee combined.

Bipartisanship

Ms. Montgomery suggests that being conservative and being bipartisan are mutually exclusive. That is a false premise.

And he has earned wide praise for tackling Medicare, the nation’s biggest budget problem, despite the political risk.

But as Washington braces for another push after the election to solve the nation’s budget problems, independent budget analysts, Democrats and some Republicans say Ryan has done more to burnish his conservative credentials than to help bridge the yawning political divide that stands as the most profound barrier to action.

Ms. Montgomery fails to mention Mr. Ryan’s two bipartisan Medicare plans. He developed the first with former Clinton Budget Director Alice Rivlin during the Bowles-Simpson Commission and negotiated the second with Democratic Senator Ron Wyden. Rivlin-Ryan (which can point to the bipartisan Breaux-Frist-Thomas as its intellectual forefather) and Ryan-Wyden are major bipartisan structural Medicare reforms. Ryan-Wyden is the Medicare policy assumed in the budget resolution passed by the House this year, even though it moved a big step left from the all-Republican plan assumed last year. Medicare is one of the biggest fiscal challenges America faces. Mr. Ryan is the only one who has made concrete legislative progress on a bipartisan Medicare plan since 2003.

Maybe Ms. Montgomery didn’t know about Rivlin-Ryan and Ryan-Wyden? Here is what she wrote on December 14, 2011 in a story titled “Paul Ryan to announce new approach to preserving Medicare”:

Working with Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden (Ore.), the Wisconsin Republican is developing a framework that would offer traditional, government-run Medicare as an option for future retirees along with a variety of private plans.

… The center formed its own debt-reduction committee, chaired by former senator Pete Domenici (R-N.M.) and former Clinton budget director Alice Rivlin, who has also worked with Ryan on his premium support approach to Medicare.

It is easy to write that someone is not bipartisan when you ignore his bipartisan work. In this case the premise is incorrect and Ms. Montgomery knows it’s incorrect.

The Biden comparison and the Commission

Ms. Montgomery contrasts Mr. Ryan with VP Biden:

Democrats say he would make a very different sort of vice president than Joseph Biden, a natural glad-hander who has taken the lead for Obama in negotiations with Republicans over taxes and deficit reduction.

We don’t know who are the Democrats who make this comparison, but we do know that VP Biden’s Communications Director, Shailagh Murray, co-authored at least six stories with Ms. Montgomery when she worked at the Post.

Like many others, Ms. Montgomery’s thesis relies heavily on Mr. Ryan’s no vote in the Bowles-Simpson Commission. Never mind that Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D) also voted no, or that President Obama quietly shelved the recommendations of this commission that he created to report to himself. Never mind that, unlike President Obama, Mr. Ryan proposed his own long-term solution after voting no, then passed it in the House.

The Ryan vote is a perfectly obvious tactical move once you understand the structure of the commission and how it interacts with fiscal negotiations. Mr. Ryan (and Mr. Camp and Mr. Hensarling) were members of a commission that reported to President Obama. Yet they, as the representatives of House Republicans, represent the opposite pole from President Obama in fiscal negotiations.

Had the House Republicans on the commission voted aye, President Obama could then have received the negotiated solution and proposed policies one big step to the left, while trying to claim that he was supporting the recommendations (as he now claims). Ryan/Camp/Hensarling (or their leaders) would then be forced to negotiate a compromise between Bowles-Simpson that they had already endorsed and a more liberal position later chosen unilaterally by President Obama. Agreeing to Bowles-Simpson would have been only the first of two rounds of concessions made by House Republicans, given that the President structured the commission so that he alone would get a second bite at the apple.

The Senate Republican appointees (Coburn, Crapo, and Gregg) voted aye in the commission, but they were able to do so in part because they knew the House Republicans were voting no. The Senate Republicans could vote to move the process along, while House Republicans saved their aye vote for a round two in which the President was at the table.

Since President Obama ignored the Bowles-Simpson recommendations, that second round instead started from scratch in the Grand Bargain negotiations between the President and Speaker Boehner, who represent and lead the two poles of the negotiation. Ms. Montgomery contrasts Mr. Ryan’s position in the commission with Speaker Boehner’s in the Grand Bargain negotiation, but Speaker Boehner was dealing directly with the President rather than as the first step in a potential two-step process. Mr. Boehner could go farther than could Ryan/Camp/Hensarling because he knew that he wouldn’t get double-dipped. Even so, President Obama tried to double-dip the Speaker when he used the Gang of Six proposal to demand $400 B more in tax increases and that the agreed-upon ceiling for revenues instead be a floor.

Senator Conrad and the Gang of Six

Ms. Montgomery includes this quote from Senator Conrad:

“His approach — my way or the highway — is precisely what’s wrong with this town. It’s the triumph of ideology,” said Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D-N.D.), who served with Ryan on the independent fiscal commission chaired by Democrat Erskine B. Bowles and former Republican senator Alan K. Simpson of Wyoming. “The hard reality is, given the fact that we have divided government, both sides have to compromise in order to achieve a result. And Paul has refused to do that.”

Let’s compare and contrast:

- During the Commission, Mr. Ryan worked with Dr. Rivlin to develop a bipartisan compromise Medicare plan. He voted no on the non-binding Bowles-Simpson recommendations, then introduced his own plan (a step to the right of B-S) in the House and passed it. The following year he renegotiated Rivlin-Ryan, compromised with Senator Wyden and produced Ryan-Wyden, included it in the House budget plan, and passed it.

- Senator Conrad voted aye on the non-binding Bowles-Simpson recommendations. He then introduced a different plan (a step to the left of B-S) as leader of the Senate’s Gang of Six. He could have used his Gang of Six plan as the basis for a bipartisan budget resolution but, at Leader Reid’s direction, chose instead to do nothing. He marked up no budget resolution. Instead, he and the Gang rolled out their plan at exactly the wrong moment. President Obama said nice things about it and upped his tax increase demand of Speaker Boehner, leading to the collapse of the Grand Bargain negotiations.

- President Obama created the commission, waited for its report, and then ignored it. He waited until Mr. Ryan proposed a budget, then attacked both the budget and Mr. Ryan in a speech at George Washington University.

Senator Conrad says the problem with Washington is the triumph of ideology. I think the problem is that certainly elected officials, including Chairman Conrad and President Obama, did not do their job.

The GW Speech

Ms. Montgomery takes a speech in which President Obama attacked Mr. Ryan and portrays the event as reflecting poorly on Mr. Ryan (emphasis is mine):

Ryan, too, blames the president. “Obama didn’t want success,” he said in November. He said that became apparent seven months earlier when Obama responded to the recommendations of the Bowles-Simpson fiscal commission by rolling out his own deficit-reduction plan. Unaware that White House aides had invited Ryan to hear Obama’s speech at George Washington University — and that Ryan was sitting in the front row — the president blasted Ryan’s budget and renewed his call for higher taxes on the wealthy.

“It became clear to me when Obama invited us to GW . . . that he wasn’t going to triangulate and embrace Bowles-Simpson. He decided to double down on demagoguery and ideology, and he has stuck to that ever since,” Ryan said.

According to Ms. Montgomery, the President was simply the victim of poor staff work. Mr. Ryan is portrayed as the aggressor. Yet in Bob Woodward’s book we read:

“We’re not waiting,” the president said in exasperation. He wanted to rip into Ryan’s plan.

… “I want to say this idea that we can’t get our deficit down without brutalizing Medicaid, it’s a dark view of America,” he said. He wanted that idea in the speech.

… Obama was getting fired up as he worked through what to say and how to say it.

I believe there was a staff foul-up in inviting Mr. Ryan to the speech, but the President’s partisan attack was neither unintentional nor staff-driven. It was a planned attack devised by President Obama that ripped into Mr. Ryan’s plan and poisoned the well. Yet somehow Ms. Montgomery portrays the President as the victim of Mr. Ryan’s “blame.”

Timing

For decades the Washington Post was the paper of record for DC. Over the past few years POLITICO has supplanted the Post in that role. When the Post’s staff publishes an obviously partisan hit piece with such weak intellectual support less than six weeks before Election Day, they destroy any credibility they have for objectivity or nonpartisan reporting. That’s a shame.

(photo credit: Chealion)