The White House has released a letter from the President to the two Senate Chairmen who are working on (different) versions of health care reform: Senator Kennedy (D-MA), Chairman of the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, and Senator Max Baucus (D-MT), Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. The letter is dated yesterday and was delivered as part of a White House meeting between the President and Senate Democratic leaders, including the two Chairmen.

This important letter attempts to shape the pending legislation. It makes new proposals, and it tries to set boundaries to constrain the work of the Chairmen. I am going to walk through the letter and explain what I think it means. I will walk through it in sequence, but will cut out the fluff, and occasionally add emphasis in bold. Each of these quotes could merit a post by itself. I will instead provide a survey of the whole letter. The first notable text is the second paragraph:

Soaring health care costs make our current course unsustainable. It is unsustainable for our families, whose spiraling premiums and out-of-pocket expenses are pushing them into bankruptcy and forcing them to go without the checkups and prescriptions they need. It is unsustainable for businesses, forcing more and more of them to choose between keeping their doors open or covering their workers. And the ever-increasing cost of Medicare and Medicaid are among the main drivers of enormous budget deficits that are threatening our economic future.

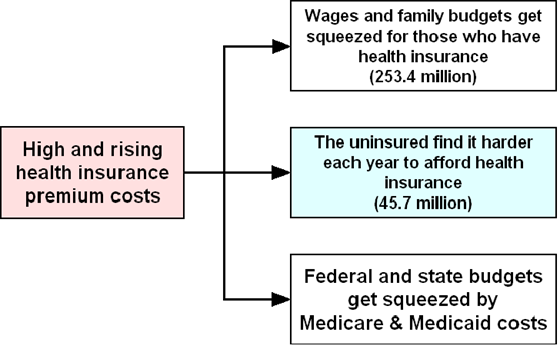

This is fantastic, especially as 2. He is focusing on health cost growth as the underlying problem, rather than just focusing on the uninsured, which is only one symptom of the problem. I wrote about this in mid-April: By focusing only on covering the uninsured, are we solving the wrong problem? Here’s the key picture from that post. We need to focus on the red box, and not just the blue box.

The President’s letter continues:

We simply cannot afford to postpone health care reform any longer. This recognition has led an unprecedented coalition to emerge on behalf of reform — hospitals, physicians, and health insurers, labor and business, Democrats and Republicans. These groups, adversaries in past efforts, are now standing as partners on the same side of this debate.

There is a less noble explanation for the existence of this coalition. I wrote in mid-May, “

At this historic juncture, we share the goal of quality, affordable health care for all Americans. But I want to stress that reform cannot mean focusing on expanded coverage alone. Indeed, without a serious, sustained effort to reduce the growth rate of health care costs, affordable health care coverage will remain out of reach. So we must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care.

This is an astonishing paragraph from a Democratic President. As he has done in the past, he says his goal is health care for all Americans, rather than health insurance for all Americans. This language will allow him to declare victory with a bill that does not provide universal pre-paid health insurance.

He then reiterates that expanded coverage is insufficient. A bill “must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care.” This is fantastic and unexpected from a Democrat.

The President’s letter then veers wildly off course. That paragraph continues:

… So we must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care. That means promoting the best practices, not simply the most expensive. We should ask why places like the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and other institutions can offer the highest quality care at costs well below the national norm. We need to learn from their successes and replicate those best practices across our country. That’s how we can achieve reform that preserves and strengthens what’s best about our health care system, while fixing what is broken.

Geographic disparities in health spending are enormous, and if we could somehow magically reduce spending in high-cost areas to match that in low cost areas, without sacrificing too much quality, then we would make major progress in reducing the level of national health spending. Budget Director Peter Orszag is the primary proponent of this argument, since before he entered the Administration.

But the Administration has no plan and no proposals that would actually reduce geographic disparities in health care. They have proposals which would provide people with more information about the health care they use, but they have not proposed to change the incentives people have to use that care. If you don’t change the incentives, you will make no significant progress in reducing geographic spending disparities or slowing health cost growth. I wrote about this in late April: Slowing health cost growth requires information AND incentives, and then found that CBO had already made this point.

More importantly, it is absurd to say that geographic disparities are “the root causes of the inflation in health care.” We know what drives health cost growth: (1) technology, (2) income growth, (3) increases in third party payment, and (4) aging of the population. Some argue that administrative costs also contribute to growth, but I’m skeptical. We also know that the first three reasons account for two-thirds to nearly all of cost growth, depending on which study you prefer.

The President’s letter correctly identifies the problem to be solved as health cost growth, and then completely misdiagnoses the sources of that growth. The Administration continues to grossly foul up the problem definition, not propose a solution, and get a free ride from a lazy and compliant press corps. You cannot slow health spending growth merely by stating a vague intent to do so.

The letter continues:

The plans you are discussing embody my core belief that Americans should have better choices for health insurance, building on the principle that if they like the coverage they have now, they can keep it, while seeing their costs lowered as our reforms take hold.

Two things jump out from this sentence. The first is a clear and oft-repeated signal that “if [you] like the coverage [you] have now, [you] can keep it.” The President says this is a core belief. It also protects the Administration from one of the most effective attacks on expansions of government health care: that it will squeeze our your private care. This is tactically smart.

The second is the return to “seeing their costs lowered as our reforms take hold.” This addresses the first box on the right side in my diagram above, and I compliment the President and his team for identifying that growing health spending hurts the more than 100 million Americans who now have health insurance, and not just those who lack it.

But for those who don’t have such options, I agree that we should create a health insurance exchange … a market where Americans can one-stop shop for a health care plan, compare benefits and prices, and choose the plan that’s best for them, in the same way that Members of Congress and their families can.

- A (singular) exchange, or 50 State exchanges? There’s a big difference.

- I have never been enamored of the “one-stop shopping” argument. I’m not opposed to it, it just doesn’t excite me. Mostly I fear that exchanges become vehicles for Washington-directed redistribution.

- It is fascinating that he takes the traditional liberal argument that “you deserve health care that is good as Members of Congress get,” and turns it into “Americans can … choose the plan that’s best for them, in the same way that Members of Congress and their families can.” This is creative.

None of these plans should deny coverage on the basis of a preexisting condition, …

The hardest problem in health care reform is how to deal with the small percentage of Americans with predictably high health costs. To quote Harvard’s Dr. Kate Baicker:

Uninsured Americans who are sick pose a very different set of problems. They need health care more than health insurance. Insurance is about reducing uncertainty in spending. It is impossible to “insure” against an adverse event that has already happened, for there is no longer any uncertainty. If you were to try to purchase auto insurance that covered replacement of a car that had already been totaled in an accident, the premium would equal the cost of a new car. You would not be buying car insurance – you would be buying a car. Similarly, uninsured people with known high health costs do not need health insurance – they need health care. Private health insurers can no more charge uninsured sick people a premium lower than their expected costs. The policy problem posed by this group is how to ensure that low income uninsured sick people have the resources they need to obtain what society deems an acceptable level of care and ideally, as discussed below, to minimize the number of people in this situation.

We need to distinguish between the uninsured and the uninsurable. The uninsured lack health insurance for a wide variety of reasons. Some uninsured are healthy, some are sick.

The uninsurable are those who are already sick or injured, and who have predictably high future health costs. If you have an incurable disease, you are uninsurable, because there is little uncertainty about your future spending. (I’m oversimplifying -there is little uncertainty that you will have high health costs.) As Kate points out, “Uninsured people with known high health costs do not need health insurance – they need health care.” The policy problem posed by this group is how to ensure that low income uninsured sick people have the resources they need to obtain what society deems an acceptable level of care.

So when the President says that “None of these plans should deny coverage on the basis of a preexisting condition,” the practical effect is that health insurance plans will be required to provide health care to the uninsurable, label it as “insurance,” and then charge healthy people higher premiums than are merited by their own health status. It’s a way of hiding the cross-subsidization.

… and all of these plans should include an affordable basic benefit package that includes prevention, and protection against catastrophic costs.

The word “basic” is unusual from a Democrat. The traditional Washington health debate has Republicans (generally) arguing that we should want more people to be able to afford access to “basic” health insurance, while Democrats (especially those farther Left) saying everyone has a right to “good” health insurance. Setting aside the access vs. right debate for the moment, the word “basic” is a more centrist choice than I would have expected from this President.

He then runs into one of the classic problems of government-designed health care reform: who defines the benefit package? By saying that all of these plans should include X, he is punting the question of who gets to define X, and how specific will they be?Governments have a terrible track record of political micromanagement of medical benefits.

I strongly believe that Americans should have the choice of a public health insurance option operating alongside private plans.

Note that he chose “I strongly believe that Americans should have” rather than the stronger “Americans must have.” Despite the urgings of the Left, the President is leaving himself room to jettison the “public option” if that is the price of getting the Republican votes he may need. Also, he says “alongside private plans,” again emphasizing that the public option will not, in his view, squeeze out private coverage. I think he’s wrong and it will squeeze out private coverage, and would point to what his Administration is trying to do to Medicare private plans as proof.

I understand the Committees are moving towards a principle of shared responsibility — making every American responsible for having health insurance coverage, and asking that employers share in the cost. I share the goal of ending lapses and gaps in coverage that make us less healthy and drive up everyone’s costs, and I am open to your ideas on shared responsibility. But I believe if we are going to make people responsible for owning health insurance, we must make health care affordable. If we do end up with a system where people are responsible for their own insurance, we need to provide a hardship waiver to exempt Americans who cannot afford it. In addition, while I believe that employers have a responsibility to support health insurance for their employees, small businesses face a number of special challenges in affording health benefits and should be exempted.

This is a fairly hard slap at a mandate (individual or employer). “I understand [you] are moving toward … I share the goal … and I am open to your ideas on shared responsibility” is not a ringing endorsement of a mandate. He then guts the universal nature by saying that it should exempt “Americans who cannot afford it” as well as small businesses. These exemptions would create tremendous distortions and inequities. The resulting patchwork mandate would be a mess. With this paragraph, I think the President weakens the prospect of a mandate becoming law.

Health care reform must not add to our deficits over the next 10 years — it must be at least deficit neutral and put America on a path to reducing its deficit over time. To fulfill this promise, I have set aside $635 billion in a health reserve fund as a down payment on reform. This reserve fund includes a numb

er of proposals to cut spending by $309 billion over 10 years –reducing overpayments to Medicare Advantage private insurers; strengthening Medicare and Medicaid payment accuracy by cutting waste, fraud and abuse; improving care for Medicare patients after hospitalizations; and encouraging physicians to form “accountable care organizations” to improve the quality of care for Medicare patients. The reserve fund also includes a proposal to limit the tax rate at which high-income taxpayers can take itemized deductions to 28 percent, which, together with other steps to close loopholes, would raise $326 billion over 10 years.

I am committed to working with the Congress to fully offset the cost of health care reform by reducing Medicare and Medicaid spending by another $200 to $300 billion over the next 10 years, and by enacting appropriate proposals to generate additional revenues. These savings will come not only by adopting new technologies and addressing the vastly different costs of care, but from going after the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, including unmanaged chronic diseases, duplicated tests, and unnecessary hospital readmissions.

- “It must be at least deficit neutral” – Good.

- “and [must] put America on a path to reducing its deficit over time” – Even better, if he were to actually propose a policy that might do this. Without such a proposal, this is empty and weak.

- “I have set aside $635 billion in a health reserve fund as a down payment on reform” – Horrible. He wants to create the entire new obligation, but fund only about half of it.

- “… cut spending by $309 billion over 10 years” – True, but his budget hides $330 B in additional spending on doctors and $17 B to expand Medicaid, so the net is a Medicare/Medicaid spending increase of $38 billion over 10 years. (See table S-5 on page 121 of the President’s budget.) The President’s budget increases spending on these entitlements, and uses a baseline game to claim budgetary savings to offset a new health entitlement.

- “… cutting waste, fraud and abuse” – This is the old chestnut to suggest that the cuts are good policy and won’t hurt. There is waste, fraud, and abuse, but the cuts will also involve real reductions in payments to health providers, and they will hurt (which doesn’t make them wrong to do).

- “… a proposal to limit the tax rate at which high-income taxpayers can take itemized deductions to 28 percent” – Democrats in Congress rejected this months ago.

- “… by reducing Medicare and Medicaid spending by another $200 to $300 billion over the next 10 years” – Excellent. Will he provide specifics? I would be happy to suggest some.

- “… and by enacting appropriate proposals to generate additional revenues.”- aka “raise more taxes” – Horrible from my perspective.

- “… going after the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, including unmanaged chronic diseases, duplicated tests, and unnecessary hospital readmissions.” – As I said earlier, these are not the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, and it is misleading and irresponsible to claim they are.

To identify and achieve additional savings, I am also open to your ideas about giving special consideration to the recommendations of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), a commission created by a Republican Congress. Under this approach, MedPAC’s recommendations on cost reductions would be adopted unless opposed by a joint resolution of the Congress. This is similar to a process that has been used effectively by a commission charged with closing military bases, and could be a valuable tool to help achieve health care reform in a fiscally responsible way.

This is new and interesting to me. “A commission created by a Republican Congress” is odd, since MedPac is not known as a nonpartisan advisory group. It is also odd to imagine giving MedPac real decision-making authority, given that it is comprised of representatives of provider groups (doctors, hospitals, nurses, etc.)

I know that you have reached out to Republican colleagues, as I have, and that you have worked hard to reach a bipartisan consensus about many of these issues. I remain hopeful that many Republicans will join us in enacting this historic legislation that will lower health care costs for families, businesses, and governments, and improve the lives of millions of Americans. So, I appreciate your efforts, and look forward to working with you so that the Congress can complete health care reform by October.

I can read this either way. My gut says this means, “Get me a bill by October.” I would prefer it be broadly bipartisan, but don’t let the lack of Republican support prevent you from getting me a bill.

Summary & Conclusions

The news in this letter is:

- The President continues his rhetorical focus on reducing long run health costs in addition to expanding coverage.

- While appearing to push for a public option and universality, he is leaving himself room to compromise on both if needed to get a bill to his desk.

- He has made a mandate harder to legislate by insisting on large exemptions, and he has not signaled any support for a mandate. Goodbye mandate, I think.

- He is insisting on deficit neutrality over 10 years and reducing the deficit in the long run, while not proposing policies that achieve either goal. He is opening the door to more Medicare and Medicaid savings to reach these goals and has floated a $200-$300 B number without specifics.

- He has opened the door to a binding commission to cut Medicare and Medicaid spending, modeled after the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process.

I have mixed conclusions:

- At the 30,000-foot level, he has broken new ground for Democrats in defining the problem correctly as unsustainable health cost growth, rather than the subsidiary problem of the uninsured. I compliment him for this.

- At the 5,000-foot level, he botches the problem definition by focusing on geographic disparities while ignoring the commonly acknowledged major drivers of health spending increases: technology, income growth, and third party payment. This is a fatal flaw.

- He continues to assert that we must slow cost growth, without proposing any policy changes that would do so in a measurable way. This is an abdication of leadership and irresponsible.

- To genuinely slow health cost growth, you need to change incentives. Doing so involves political pain. Congress will not want to do that pain, and will not do so if the President doesn’t propose specifics.

- In addition, the short-term budget numbers still don’t add up. He has problems with the “down payment” meaning they’re not paying for the full new obligation, ignoring the doctors and Medicaid spending hidden in the baseline, and Congress rejecting his biggest tax increase proposal.

- I am glad that he is leaning against, or at least undermining, the case for a mandate.

- The MedPAC idea is interesting. It probably won’t work, but I don’t want to dismiss it out of hand.

The President’s letter makes it harder, not easier, to get a bill. While I like some elements of the letter, it is inconsistent with the President’s actual proposals. You cannot magically slow health spending growth without proposing policy changes that affect incentives and behavior. If the President is not willing to bite the bullet and lead on slowing long-term health cost growth, he will instead get a bill which is just a straight entitlement expansion, partly offset by Medicare Advantage cuts and tax increases, and obscured by budget gimmicks. His advisors will then have to construct a bogus argument that they have addressed long-term spending growth.

That would be a terrible outcome.