Conventional wisdom says the tenure of President George W. Bush was dominated by partisanship. There were deep partisan splits over the war in Iraq, enhanced interrogation, wiretapping, the 2003 tax cuts, and Social Security reform.

This conventional wisdom ignores significant bipartisan legislative accomplishments led by President Bush. I will focus on domestic policy accomplishments.

Each of the following major laws was enacted on a bipartisan vote:

- The 2001 tax cuts;

- the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001-2;

- the 2002 extension of Trade Promotion Authority;

- the 2003 medicare law;

- the 2005 energy law focused on electricity;

- the 2006 pension reform law;

- the 2007 energy law focused on fuel;

- the 2008 stimulus law;

- the 2008 housing reform law; and

- the 2008 TARP law.

President Bush also reached across party lines to reform immigration law. His bipartisan outreach on this issue was successful, but the legislation failed due to opposition from both wings. In that effort President Bush’s team negotiated with a broad group in the Senate, led by Senator Kennedy on the left and Senator Kyl on the right. President Bush’s attempts deeply split his own party, yet he persisted until it became apparent there was not a 60 vote coalition to succeed.

I imagine some readers are skeptical of the above list so, once again, I’m going to show you some pictures. I’m going to show you a lot of pictures. I want to hammer home the Bush-bipartisan success point. I will then try to draw some lessons for Team Obama.

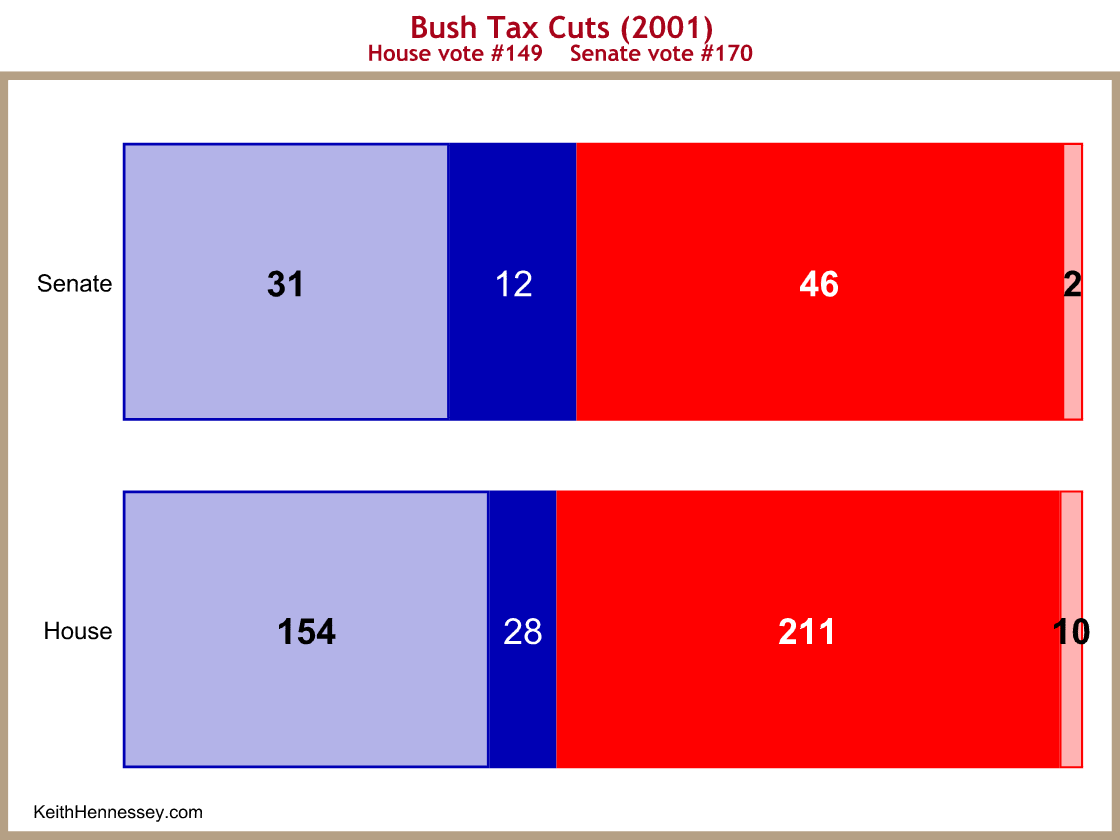

Let’s begin with the 2001 tax cuts to orient ourselves to the graph format.

- Dark shading means they voted aye. Light shading means they voted no. So in the top bar in this first graph, 12 Democrats and 46 Republicans voted aye, while 31 Democrats and 2 Republicans voted no.

- Blue shows Democrats and independents caucusing with Democrats (like Senators Lieberman and Sanders).

- Red shows Republicans.

- I left out those who didn’t vote, which explains why many Senate votes don’t total 100, and many House votes don’t total 435.

- In each case I tallied the vote on final passage.

- As always, you can click on any graph to see a larger version.

On final passage of the Bush tax cuts of 2001:

- in the Senate 46 Republicans and 12 Democrats voted aye, while 2 Republicans and 31 Democrats voted no; and

- in the House 211 Republicans and 28 Democrats voted aye, while 10 Republicans and 154 Democrats voted no.

It should be fairly easy to see that the 2001 tax cuts were enacted by a center-right coalition. Almost all Republicans supported the final product, and about 1 in 4 (Senate) or 1 in 6 (House) Democrats voted aye.

This bill was bipartisan largely because the Bush White House, Senate Majority Leader Lott and Senator Grassley worked closely with Democratic Senators Breaux and Baucus to craft a bill and keep moderate Democratic Senators onboard. We used the reconciliation process, and therefore had 58 votes when we needed only 51 for final passage in the Senate.

You can see that the 2001 tax cuts would not have had even a simple majority in the Senate if Republicans had acted alone. The Senate was split 50-50 at the time.

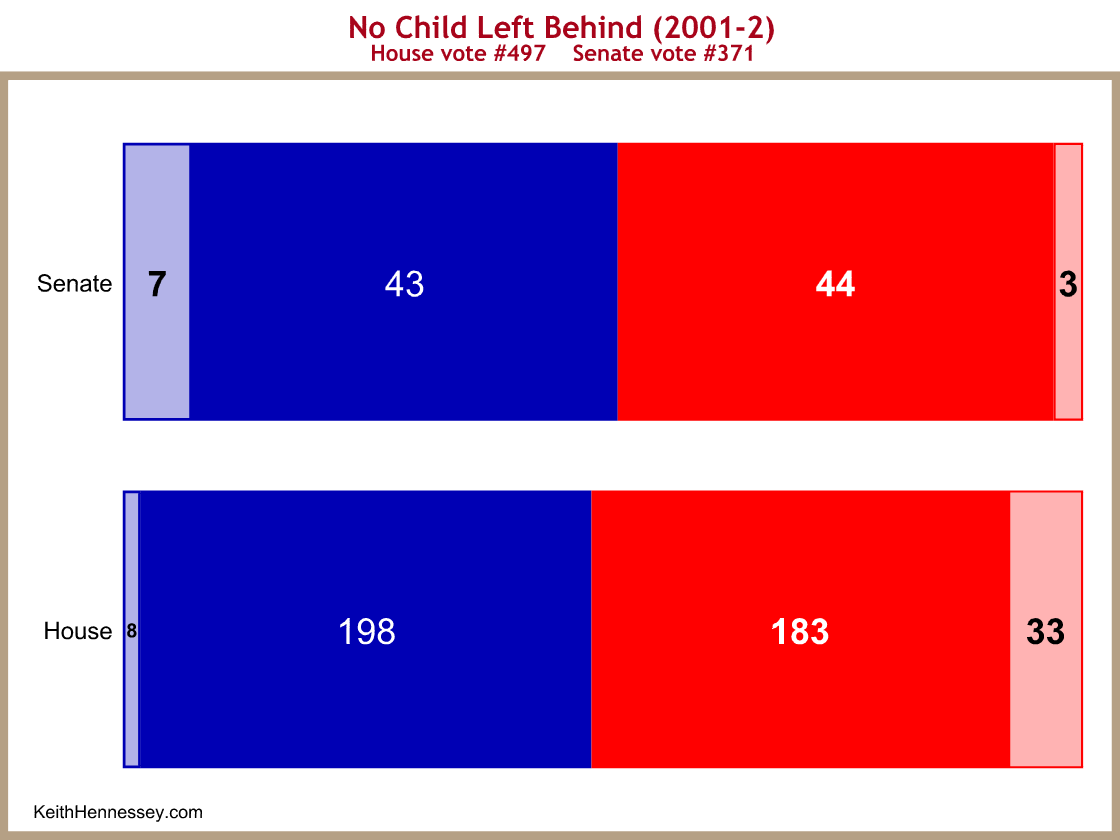

Now let’s turn to education.

This was a broad bipartisan coalition. President Bush reached out to Senator Kennedy and instructed his team to negotiate directly with Kennedy. You can see the result. This is about as bipartisan as it gets for major legislation.

The Senate was a 51-49 Democratic majority when this bill became law.

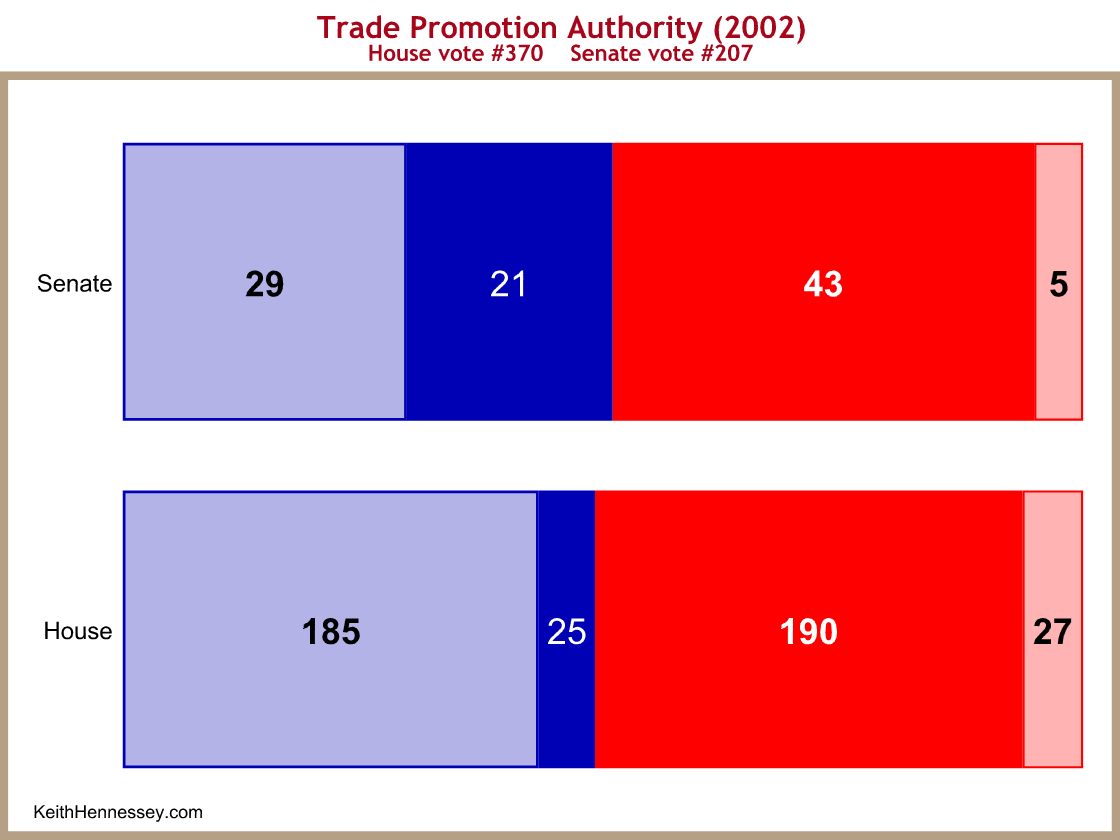

Next up, trade.

Trade Promotion Authority, formerly known as fast track, gives the President authority to negotiate trade deals with other countries and have them subject to only an up-or-down vote by Congress, rather than being amended to death. It is essential for Congress to give the President this authority if you’re to have free trade agreements.

Again you can see the center-right coalition that dominates much of American economic policymaking. This has even a little more Democratic support than the 2001 tax cuts, and slightly more opposition from protectionist Republicans. As with the 2001 tax cut, you can see that there are more economic centrist Democrats in the Senate than in the House.

This bill could not have passed either the House or the Senate with only Republican votes. A bipartisan coalition was necessary for legislative success.

This is with a 51-49 Democratic majority in the Senate.

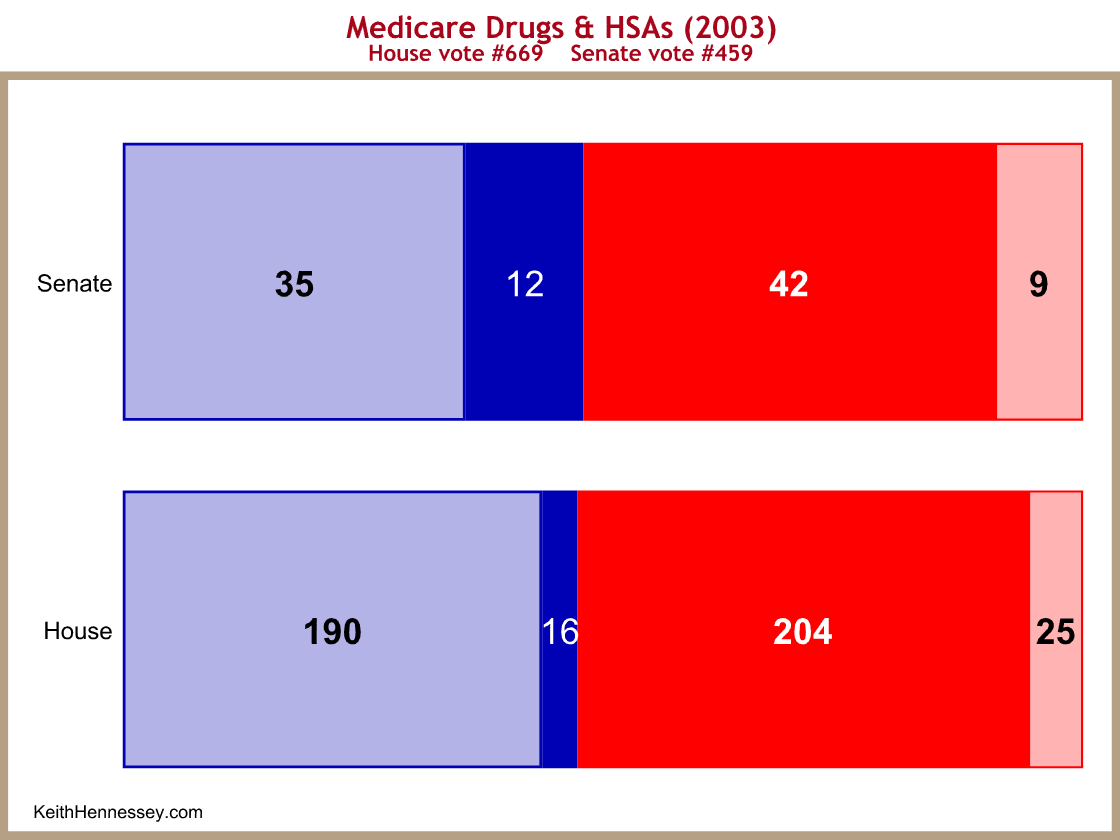

Medicare and Health Savings Accounts are next.

Now we’re back to a Republican majority in the Senate.

Once again, President Bush, his team, and Senator Grassley worked closely with centrist Democratic Senators Baucus and Breaux to negotiate a deal. The final details were hammered out in a fierce negotiation between Baucus/Breaux and Rep. Bill Thomas (R-CA), with extensive White House support.

President Bush held a few meetings at the White House with Baucus, Breaux, and the key Republicans to strengthen the coalition and keep the ball moving forward. This bill created the Medicare drug benefit (which split Republicans) and Health Savings Accounts (which Republicans and conservatives especially like). Democratic leaders opposed this bill, but we managed to hold Democratic moderates anyway.

Once again, the winning majority coalition in both the House and Senate was bipartisan, and the bill could not have become law without Democratic support. A key vote before Senate final passage was a cloture vote, in which some of the 9 Republicans who ultimately voted no supported cloture.

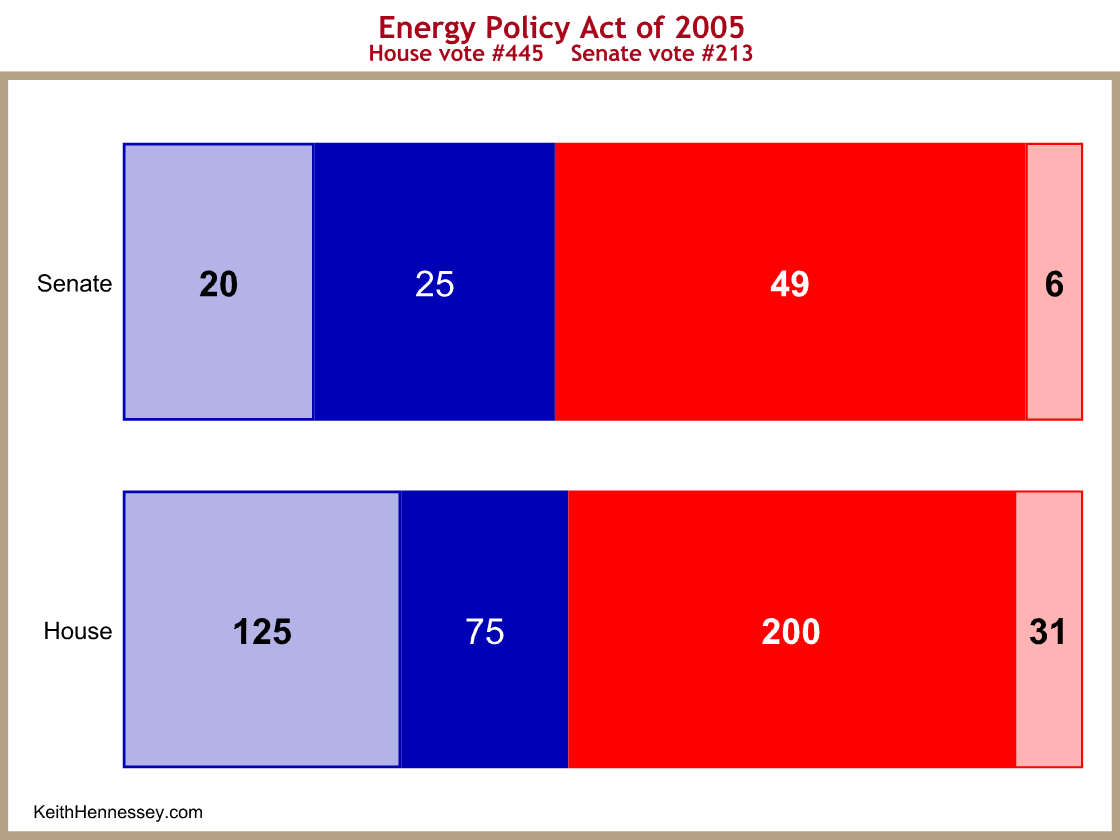

Now we turn to the first major energy law during the Bush tenure.

Senators Bingaman and Baucus were key to this legislative success, which you can see was more bipartisan than some of the prior successes. The legislative process was filled with amendments and negotiations across the partisan aisle and fierce regional conflicts.

Senate Democrats split roughly equally and 75 House Democrats supported final passage. This law focused on electricity (rather than fuel), which sometimes has more of a regional policy focus than a partisan split. This bill originated with VP Cheney’s Energy Task Force, which was labeled by the Left as a dark and evil conspiracy. And yet the final legislation had significant bipartisan support.

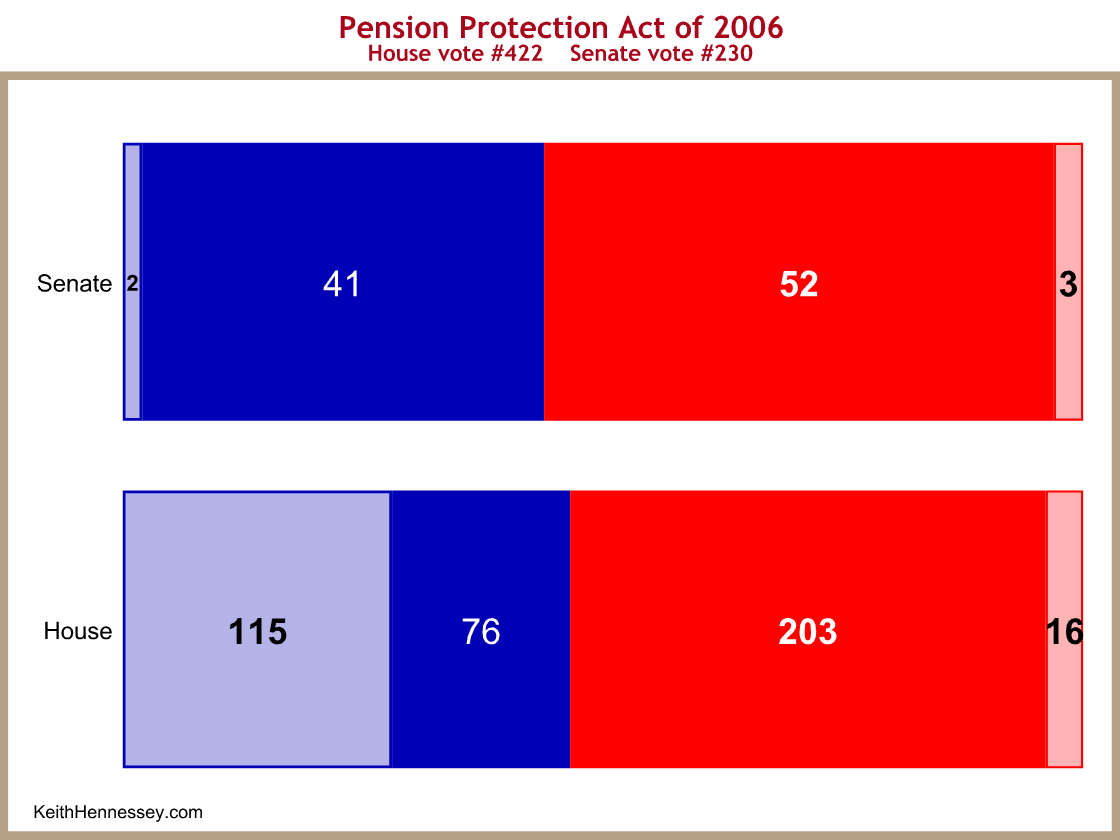

Pension reform gets less attention than the others but is important.

I highlight this law because it is easy for pension issues to break down along party lines, with Republicans favoring management interests, Democrats favoring labor interests, and the taxpayer getting shafted. Republican committee chairmen and the Bush Administration reached across party lines to elevate the interests of protecting the pension system, future retirees, and taxpayers, battling against tremendous lobbying pressure from business and labor interest groups to relax the pension rules and allow pension plans to be underfunded.

The law was far from a complete victory for good pension policy, but it was a definite improvement over what preceded. And again, you can see the tremendous breadth of bipartisan support.

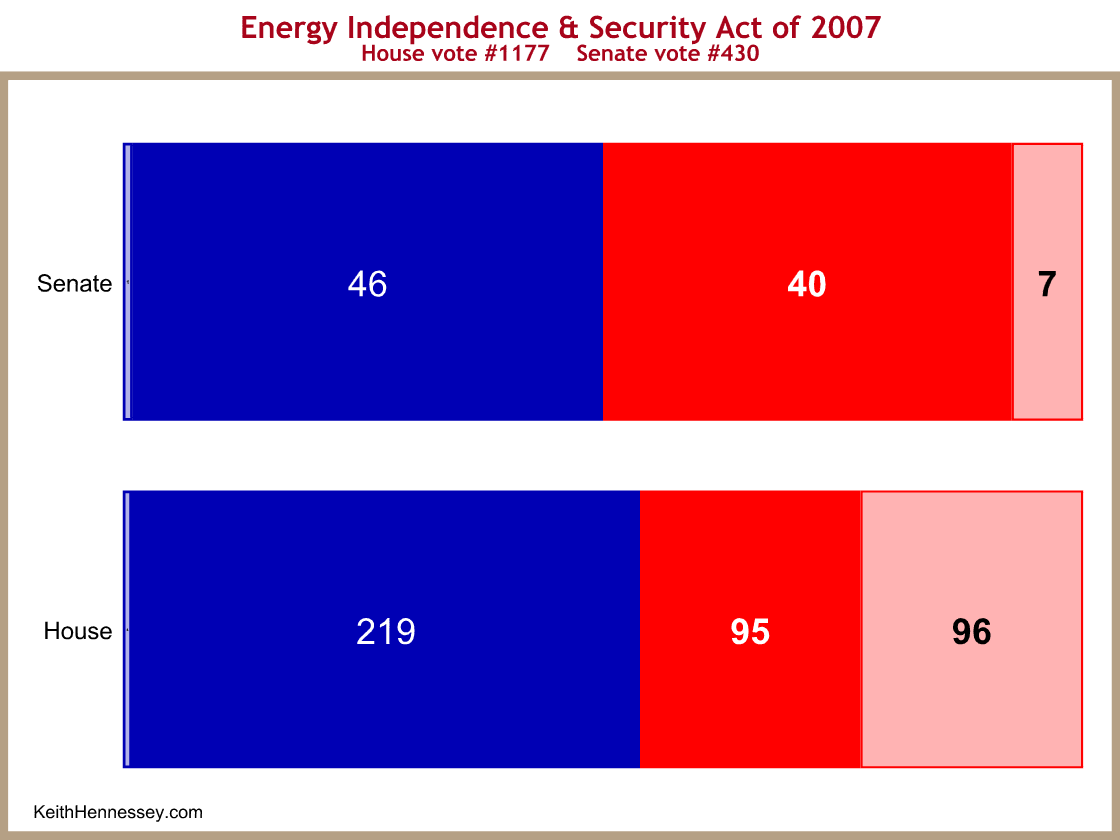

Still in President Bush’s tenure, we now shift to Democratic majorities in the House and Senate. The 2007 energy law focused on fuel.

In the 2007 State of the Union Address, President Bush proposed to increase fuel economy standards (CAFE), and to increase the mandated amount of renewable fuels (ethanol) that had to be blended with gasoline. This “energy security” proposal infuriated conservatives – the Wall Street Journal editorial page trashed us for it all year. The President recognized that, with new Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, he would have to build a different legislative coalition than had worked for him when his own party was in the majority.

The final bill was negotiated via an exchange of letters between the Bush White House and Speaker Pelosi. You can see unanimous Democratic support and Republicans deeply split, especially in the House. As with his unsuccessful immigration reform efforts, President Bush was willing to negotiate a compromise with leaders and even wingers from the other party.

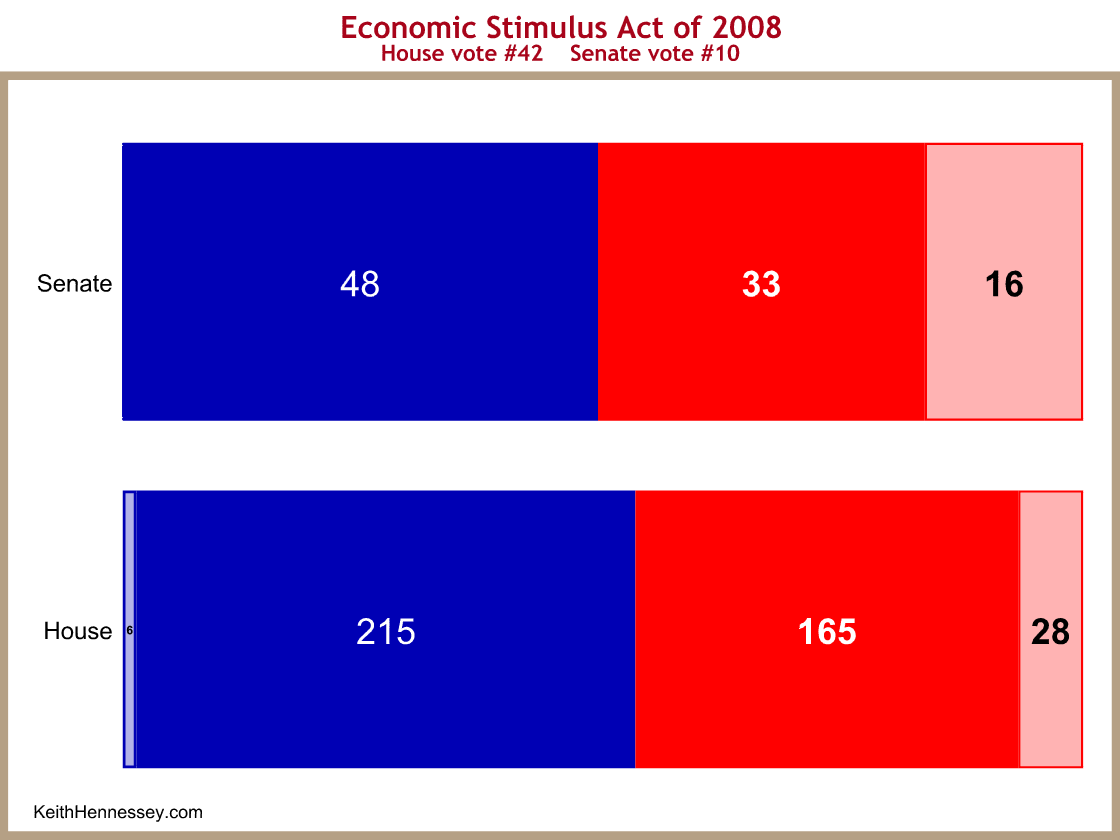

Next is the early 2008 stimulus law.

Before announcing his stimulus proposal, President Bush called Speaker Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Reid to brief them on it. They urged him to propose a broad outline rather than detailed specifics. President Bush agreed to do so.

President Bush hosted a meeting with the bipartisan / bicameral leaders to discuss the stimulus, similar in composition to the upcoming Blair House meeting. That Cabinet Room meeting was unproductive.

The President then assigned his Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, to negotiate directly with Speaker Pelosi and Minority Leader Boehner. The three of them negotiated a compromise that followed the President’s outline, and that the President, Speaker, and Minority Leader supported. Almost all Democrats supported the bill, as did most Republicans, but with a significant contingent voting no.

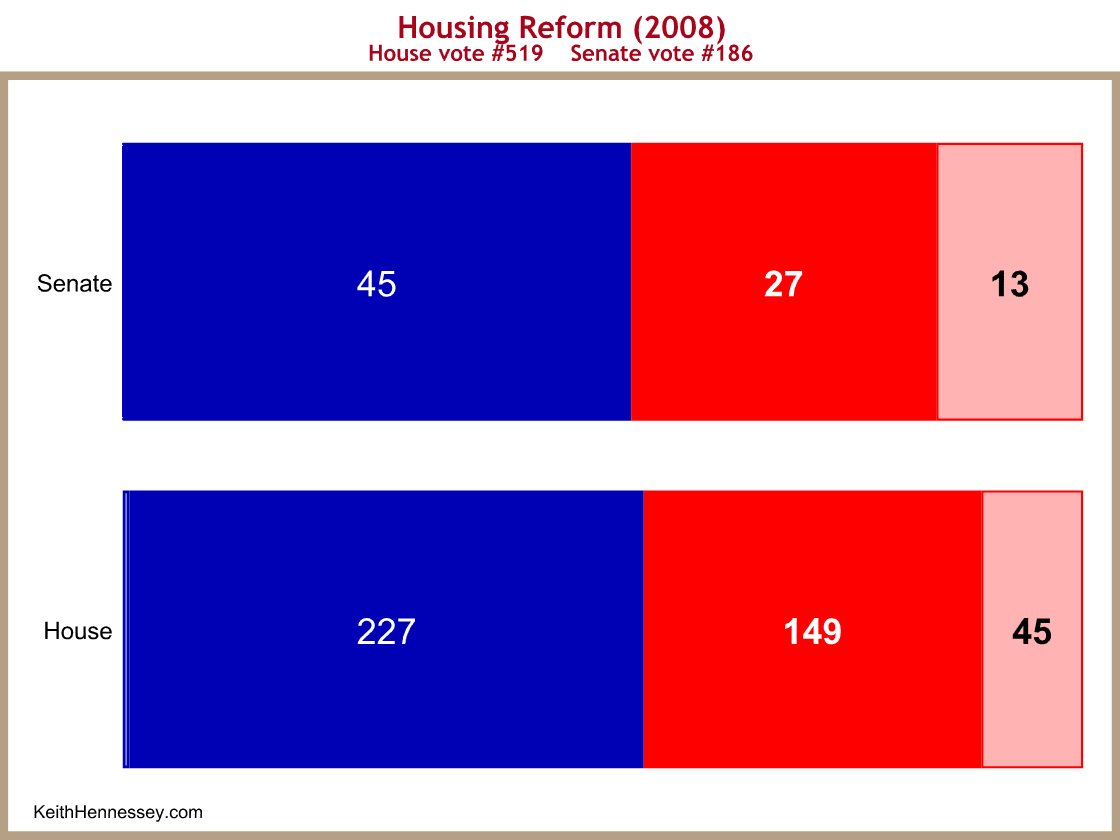

Housing reform legislation was stuck for a long time until Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac started to collapse. Then it suddenly broke free.

Again you can see the results of negotiations between a Republican President and a Democratic-majority House and Senate. The bill had unanimous Democratic support and a fairly serious split on the Republican side.

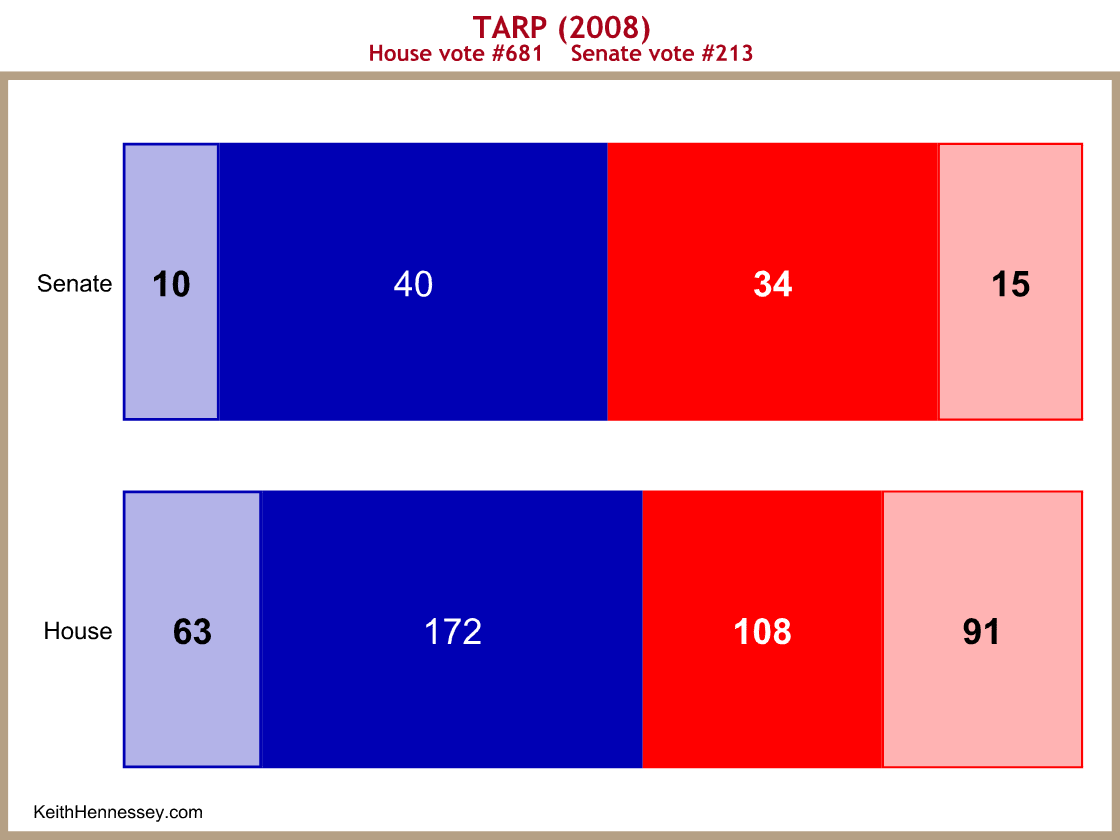

Finally we have the TARP.

The first version of TARP was negotiated by Secretary Paulson with Democratic and Republican leaders and committee chairmen in an intense and conflict-ridden negotiation. The legislation failed spectacularly on the floor of the House the first time. The President’s team then negotiated by phone with House and Senate leaders of both parties, leading to a few modifications to the original package. The Senate formed a broad center-out coalition to pass the bill easily, which then succeeded the second time around in the House.

You can see broad bipartisan support, as well as significant opposition from both parties. As with the 2007 energy law and the 2008 stimulus, the 2008 TARP was enacted with Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, with leaders from the opposite party working out compromises with a Republican President.

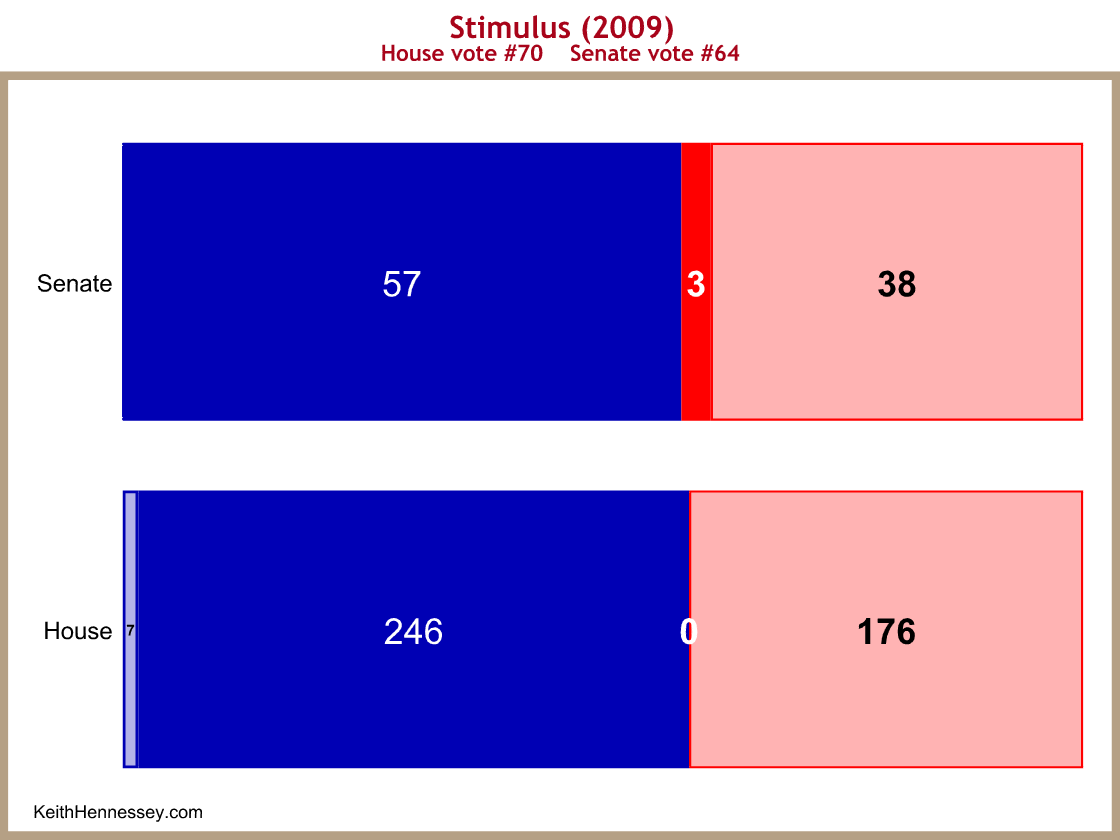

Now we turn to the three big domestic policy issues of President Obama’s tenure so far. We begin with the February 2009 stimulus.

Other than three Senate Republicans, the bill was passed and became law on party line votes. There were no negotiations with Congressional Republicans.

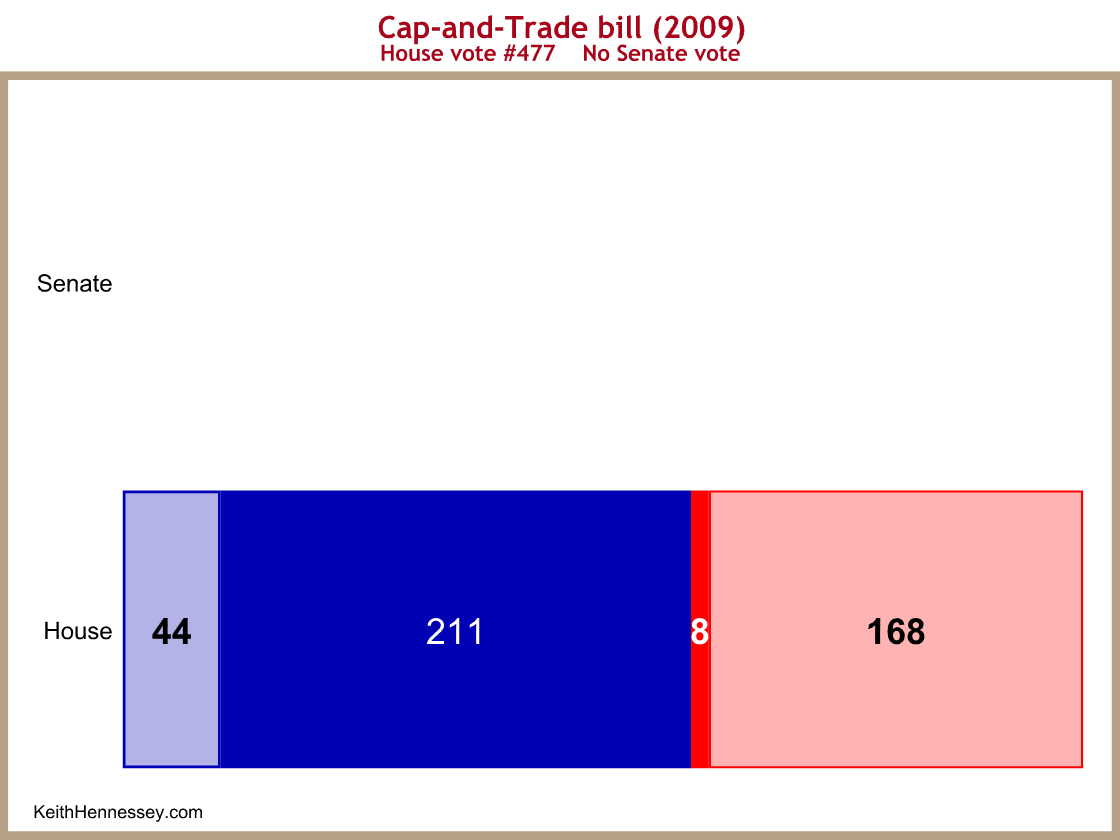

Cap-and-trade is next, but only in the House.

Eight House Republicans voted for the bill, providing Speaker Pelosi with her winning margin. A significant block of Democrats voted no.

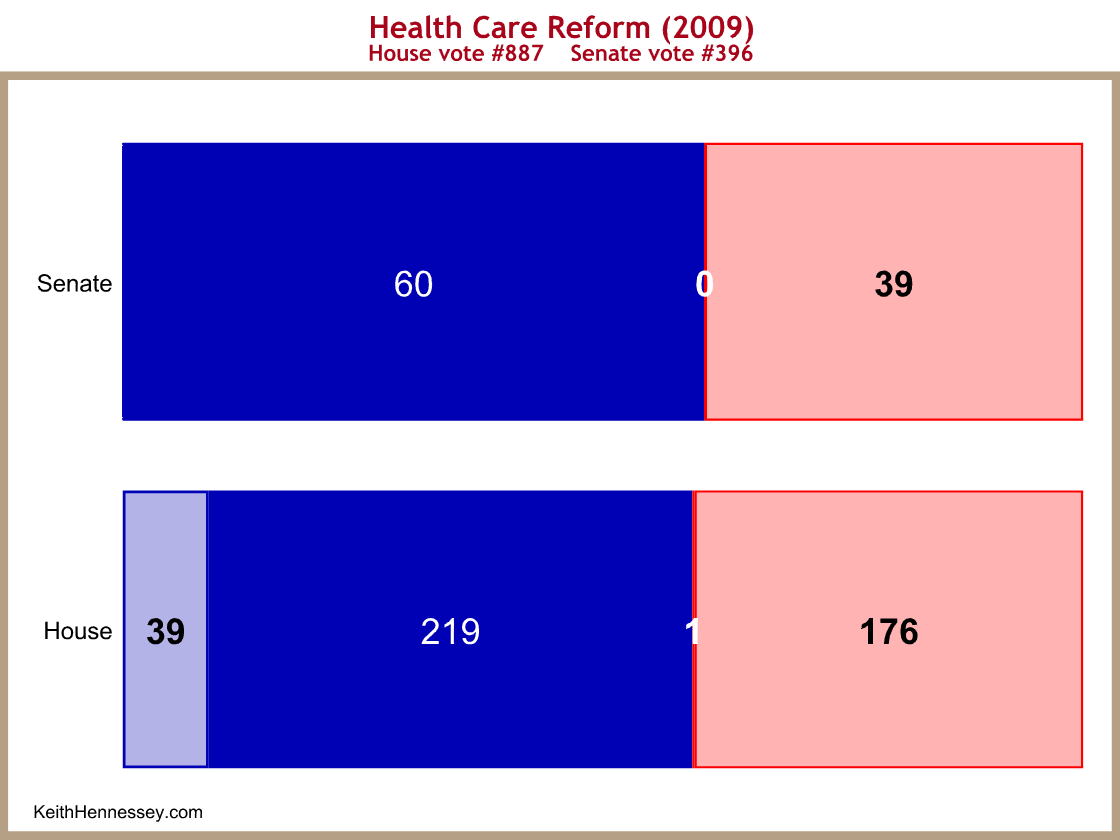

We end with the health care bills that are the subject of this Thursday’s meeting.

Once again you can see straight partisanship.

Observations and common threads

Senate Republicans peaked at 56 votes during Bush’s tenure.

President Bush used reconciliation twice three times: once in 2001 for the bipartisan tax cuts, once in 2003 for the partisan tax cuts (not shown), and once in 2005 to cut spending.

In all other cases he had to deal with potential filibusters, occasionally from both sides of the aisle.

In Republican majority Congresses, the winning margin was often provided by Democrats, especially in the Senate.

There are at least four different versions of a bipartisan vote:

- Unifying your own party (or nearly so) and picking off a moderate block from the minority: tax cuts, TPA, Medicare/HSAs. You do this by trying to split the other side’s moderates from their party leaders.

- Picking up the majority of the other party, at the cost of a losing a significant block from your own side: 2005 energy, TARP. You do this by negotiating with the other party’s leaders.

- Working with the majority of the other party and getting all of their side while your own side splits deeply: 2007 energy, 2008 stimulus, housing. You do this by negotiating with the other party’s leaders when they’re in the majority.

- Near consensus: No Child Left Behind, Pension Protection Act (in the Senate). You do this by negotiating with everyone. Miracles occasionally happen.

Why did Bush succeed at enacting bipartisan legislation?

I assume that some on the Left will say the Republican minority is now far more unified, partisan, and obstinate than the Democratic minority ever was. I think this is silly. Whatever you think of Republicans, they’re not that unified. I’m reminded of the organized crime boss in the movie Sneakers: “Don’t kid yourself. It’s not that organized.”

I believe there are six keys to President Bush’s bipartisan legislative successes:

- He sometimes reached out to Congressional Democrats and negotiated directly with them, even at the expense of upsetting his Congressional Republican allies.

- He knew how to count votes, and when not to rely on a razor-thin partisan margin for victory.

- He knew how to nurture existing bipartisan discussions and alliances in Congress and turn them to his own advantage.

- He was willing to preemptively split his own party when necessary to get a deal.

- He knew when and how to split the other party, negotiating with Democrats who were potential supporters of a compromise and isolating those who would oppose a deal no matter what.

- He and his allies generally stuck with a traditional legislative process, which builds credibility and makes members feel they are getting their fair shot, even if they lose a vote.

President Obama needs to learn each of these lessons if he wants to succeed as President Bush did.

- President Obama explains that his proposals include {modified versions of) Republican ideas. That’s not how you bring the other party on board. You can end up at the same place by bringing members of the other party into the room and negotiating with them. Then they (in this case, Republicans) have ownership of the compromises and are more likely to support the final product. The way you get someone to agree is by bringing him into the room and negotiating with him (or her). Make the other guy feel like he got a win.

- For a year he tried to enact legislation by relying on a universe of 60 votes from which he needed 60. That’s nearly impossible to do on any important issue, especially when you simultaneously provoke the other 40 to stand firm by shutting them out.

- On health care he undercut Senate Finance Committee Chairman Baucus, whose bipartisan “Gang of Six” had the best chance to negotiate the core of a bipartisan compromise. Recently Leader Reid blew up a Baucus-Grassley deal on the jobs bill, further poisoning the water for any potential future bipartisan efforts. No Senate Republican can now have confidence that any Democratic committee chairman has the authority to negotiate a binding deal. Why should Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham enter into bipartisan cap-and-trade negotiations after he saw what Reid did to Baucus-Grassley?

- President Bush alienated a significant share of his own party when he announced his 2007 energy proposal, his 2008 stimulus proposal, immigration reform, and the TARP. On cap-and-trade and especially health care, President Obama has instead tried to hold onto his left wing as long as he possibly could, making the inevitable break even more painful and losing the ability to demonstrate to Republicans that he is willing to make hard choices in his own party to bring Republicans onboard.

- Bipartisan doesn’t always mean negotiating with the leaders of the party. You have to know when to negotiate with the opposition leaders, when to negotiate with a winger from the other party (e.g., Bush-Kennedy on education, or Bush-Kennedy-Kyl on immigration), and when to try to pick off a few moderates from the other party to squeak out your margin of victory. Other than Speaker Pelosi picking off eight House Republicans for cap-and-trade, Team Obama and Congressional Democrats have failed with each of these tactics. But have they actually tried?

- The traditional legislative process creates legitimacy within the halls of Congress. Committee markups, bipartisan negotiations, open amendment processes, and traditional open conferences are processes that create predictability, order, and a sense of fair play. It is much easier to cultivate members of the minority party when they perceive you are playing by the rules. Team Obama and their allies repeatedly try to bypass the rules, creating new substantive products behind closed doors and relying upon nontraditional legislative processes. This undermines both public confidence and the minority’s willingness to play ball. If Senator Reid were to allow floor amendments to be offered to major legislation, even amendments he might lose, he might not face quite so many filibusters and failed cloture votes.

If President Obama wants bipartisan legislative success, he could learn a few things from his predecessor.

(photo credit: Official White House photo by Eric Draper)