(Editorial note: I was doing so well moving to shorter posts. I fail miserably in achieving that goal here. I went the comprehensive route instead. I promise to return to shorter posts in the future. Buckle up – this is a long ride. I hope you find it’s worth it.)

(Update: There’s an important correction in #3 below. The estimated job loss for the option I think most closely approximates the Administration’s proposal should be about 50,000 over five years, rather than about 150,000 over five years. I apologize for the error.)

There is not yet much data available on the President’s CAFE announcement. Luckily, we have a huge base of analysis that the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) did in 2008 that allows us to infer a lot from what was announced. Here are the specific data points we have from the President’s announcement:

- The average fuel economy standard will be 35.5 mpg in 2016. That’s a weighted average of all cars and light trucks sold in the U.S.

- Assuming that the Wall Street Journal’s reporting is accurate, they would require cars to hit 39 mpg by 2016, and light trucks to hit 30 mpg by 2016.

These fuel standards are the implementation of a law proposed by President Bush in January 2007, and passed by (a Democratic majority) Congress and signed by President Bush in December, 2007. The Bush Administration developed rules to implement the law and brought them right up to the goal line, but did not finalize them before the end of the Administration.The Obama Administration has now significantly modified the Bush rules.

Technically the Administration is today announcing that they will release a new proposed rule. While the news coverage makes it sound like this is a done deal, this is the beginning of a regulatory process, not the end. Still, the starting point is extremely important.

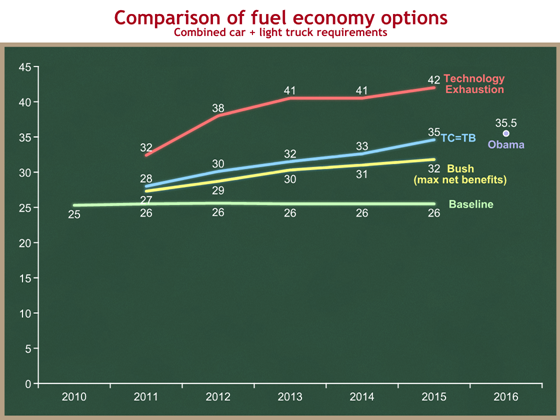

In developing the Bush proposal, NHTSA developed six options. I will show you four of those. Conveniently, what we know about President Obama’s proposal lines up almost perfectly with one of those options. This allows us to use NHTSA analysis of this option to make some initial estimates of the effects of the President’s new proposal. As always, you can click on the graph to see a larger version.

This graph shows the fuel economy requirements, in miles per gallon (mpg), for a nationwide fleet average. In actuality there will be two standards, one for cars and one for light trucks (SUVs are light trucks). It gets even more complex than that, because the standard adjusts for vehicle footprint (the shadow made by the vehicle when the sun is directly overhead). This incorporates an element of vehicle size in the requirement as a proxy for safety. If everyone just moved to tiny little vehicles, we would get much better fuel economy, but we would also have more highway fatalities. So the NHTSA methodology balances fuel efficiency and safety. The “S” in NHTSA stands for Safety. For reasons that I fail to understand, safety sometimes gets taken for granted in the Beltway policy debate relative to fuel efficiency, environmental benefits, and economic costs.

The four lines are from NHTSA’s analysis for the rule that we (the Bush Administration) did not quite finalize:

- Green is the baseline – what the standard would be if the Administration did nothing.

- Yellow shows the Bush proposal. This line is the result of a methodology that tries to maximize net societal benefits (= total societal benefits minus total societal costs).

- Blue shows a different methodology, in which the standard is raised until total societal costs equal total societal benefits, so net societal benefits equals zero. This is the highest you can go before the model says that the rule is making society (in the aggregate) worse off, taking into account all costs and benefits. This line and option are labeled TC=TB.

- The red line is the extreme upper end of what NHTSA thinks can be done if all manufacturers use every fuel economy technology available, without regard for cost. No one suggests it is a viable policy option, but it is a useful reference.

The purple dot is what we know about the Obama proposal. We only have a 2016 figure, which is conveniently right in line with the TC=TB option analyzed by NHTSA last year. So I’m going to make an assumption that the Obama proposal roughly matches this blue line in the intervening years. When I compare the separate numbers we have from the Administration for cars and light trucks with the six NHTSA options, they line up in a similar fashion with the TC=TB option, reinforcing my view that this is a solid assumption. This means I will use the NHTSA estimates of the TC=TB blue line option as a proxy for the effects of the Obama proposal. Technically, someone can quibble that it’s not precisely identical, but until I see data to the contrary, that’s just quibbling.

This means the Administration can dismiss the entire analysis that follows by saying their proposal differs from the TC=TB option. I cannot disprove such a claim if they make it, but my response would be, “How different? Show me.” I feel quite comfortable using this option for my own analysis, and will do so until presented with an alternate set of numbers by the Administration. (I helped coordinate much of this policy process for President Bush in 2007 and 2008.)

Here are ten things you might want to know about President Obama’s new fuel economy proposal. I will reference some tables and analysis from the NHTSA analysis done for the near-final Bush rule. This is a long list, so this summary will let you skip around as you like:

- It’s aggressive.

- Rather than maximizing net societal benefits, this proposal raises the standard until (total societal benefits = total societal costs), meaning the net benefits to society are roughly zero. This is not an invalid framework for making a policy decision, but it is unusual. It represents a different value choice.

- NHTSA estimated that a similar option would cost almost 150,000 50,000 U.S. auto manufacturing jobs over five years.

- NHTSA guesses that under a similar option, manufacturers will make huge increases in dual clutches or automated manual transmissions, a big increase in hybrids, and medium-sized increases in diesel engines, downsizing engines, and turbocharging.

- It will have a trivial effect on global climate change.

- The national standard = the California standard (roughly).

- The auto manufacturers got rolled by the Governator.

- Granting the California waiver means California has leverage for next time.

- In Washington, EPA is now in the driver’s seat, not NHTSA.

- Today’s action will accelerate EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from stationary sources. While Congress is futzing around on a climate change bill, EPA is getting ready to bring their “PSD” monster to your community soon.

You can see this from the graph above. Within the Bush Administration we considered a range of options that would raise average fuel economy by between 1% per year and 4% per year. Our near-final rule would have raised this combined car/truck average about 4.7% per year from 2010 through 2015. My math shows that the Obama proposal would raise this same measure about 5.8% per year through 2016. That’s really aggressive. (In this post all years are Model Years for vehicles.)

Note: The press is reporting that Team Obama says they’re doing about +5% per year. They’re measuring starting in 2011.I use 2010 so I can compare Bush and Obama.

2. Rather than maximizing net societal benefits, this proposal raises the standard until (total societal benefits = total societal costs), meaning the net benefits to society are roughly zero. This is not an invalid framework for making a policy decision, but it is unusual. It represents a different value choice.

The NHTSA analyses look at a range of benefits to society, including economic and national security benefits from using less oil, health and environmental benefits from less pollution, and environmental benefits from fewer greeenhouse gas emissions (this is new). They also consider the costs, primarily from requiring more fuel-saving technologies to be included by manufacturers. NHTSA assumes these increased costs are passed on to consumers. More expensive cars mean that fewer cars are sold, which means that fewer auto workers are needed. NHTSA calculates economic costs to car buyers and to society as a whole, and job losses among U.S. auto workers.

A standard rule-making methodology is to look at all the costs to society, and all the benefits, and make them comparable (by converting them into dollar equivalents). You then ask, What policy will maximize the net benefit to society as a whole, taking into account all costs and benefits? This is the approach NHTSA used in building the yellow line.

The blue line represents a different approach. (See the TC=TB line on Table VII-6 on page 613 of the NHTSA analysis.) You take the same analysis of costs and benefits, but instead ask, How much can we increase fuel economy before the costs to society as a whole outweigh the benefits to society as a whole? This results (in theory) in no net benefit (and no net cost) to society, but allows you to maximize the fuel economy subject to this constraint.

The Obama Administration’s numbers are in line with this latter approach. It’s not wrong. The Obama approach is quite different. It represents a different value choice, in which a higher priority is placed on the benefits of increased fuel economy, and lower priorities are placed on increased costs to car buyers and job loss in the auto industry.

3. NHTSA estimated that a similar option would cost almost 150,000 50,000 U.S. auto manufacturing jobs over five years.

Update: I was sloppy and missed the note on page 585 which said that table VII-1 shows cumulative job losses. Thus, the total over five years is 48,847 (which I’ll write as “almost 50,000”), and not the 148,340 I earlier calculated. I apologize for the error, and thank James Kwak for catching my mistake.

See Table VII-1 on page 586 of the NHTSA analysis. NHTSA estimated that the TC=TB option, which I’m using as a proxy for the Obama plan, would result in the following job losses among U.S. auto workers:

|

MY 2011 |

MY 2012 |

MY 2013 |

MY 2014 |

MY 2015 |

5-yr total |

|

8,232 |

24,610 |

30,545 |

36,106 |

48,847 |

148,340 |

Compared to the Bush draft final rule, this is 118,000 37,000 more jobs lost.

Since I know this table is inflammatory, I will anticipate some of the responses:

- This is an estimate for the job loss from the TC=TB option analyzed by NHTSA in 2007. This is the closest proxy for the Obama rule, and I’m convinced it’s a good proxy until someone demonstrates otherwise. But technically, it’s not a job loss estimate for the Obama proposal.

- This estimate was done in a different economic environment (late 2008), and before the U.S. government owned 1.5 major U.S. auto manufacturers. My guess, however, is that these changed conditions should push the estimated job loss up from the above estimate, rather than down.

- There’s a false precision in the above table. It’s just what NHTSA’s model spits out. I draw this conclusion: The Obama plan will increase costs enough to further suppress demand for new cars and trucks. This will cause significant job loss, and probably in the 150K 40K range over 5-ish years, with a fairly wide error band. I don’t put any weight on the precise annual estimates.

4. NHTSA guesses that under a similar option, manufacturers will make huge increases in dual clutches or automated manual transmissions, a big increase in hybrids, and medium-sized increases in diesel engines, downsizing engines, and dialing back turbocharging.

NHTSA does a detailed analysis of the costs of new technologies to improve fuel efficiencies, and they talk to the manufacturers and examine their product plans. They then guess what technology changes the manufacturers might make to comply with a higher fuel efficiency standard. Here are their estimates for increased penetration in MY 2015 for various technologies under the TC=TB / Obama proxy option. This is from Table VII-7:

|

Baseline |

TC = TB (Obama proxy) |

Increased penetration |

|

| Dual clutch or Automated manual transmission |

8% |

60% |

+52% |

| Hybrid electric vehicles |

0% |

24% |

+24% |

| Turbocharging & engine downsizing |

11% |

24% |

+13% |

| Diesel engines |

0% |

12% |

+12% |

| Stoichometric gasoline direct injection |

30% |

39% |

+9% |

It would be great it if a commenter could educate us a little on these technologies.

5. The proposal will have a trivial effect on global climate change.

I always chuckle when elected officials boast about the number of tons of carbon that a policy proposal will not inject into the atmosphere. The White House is doing so today, emphasizing “a reduction of approximately 900 million metric tons in greenhouse gas emissions.” That sounds like a a lot, but who the heck knows?

We are fortunate that NHTSA analyzed the climate effects of all six options in terms more amenable to our comprehension.Here are their estimates for baseline, the Bush option, and the TC=TB (Obama proxy) option. This data is from Table VII-12 in the NHTSA analysis:

|

CO2 concentration (ppm) |

Global mean surface temperature increase (deg C) |

Sea-level rise (cm) |

|||||||||

|

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

|||

| Baseline |

455.5 |

573.7 |

717.2 |

0.874 |

1.944 |

2.959 |

7.99 |

19.30 |

37.10 |

||

|

Bush |

455.4 |

573.2 |

716.2 |

0.873 |

1.942 |

2.955 |

7.99 |

19.28 |

37.06 |

||

| TC=TB(Obama proxy) |

455.4 |

573.0 |

715.6 |

0.873 |

1.941 |

2.952 |

7.99 |

19.27 |

37.04 |

||

OK, this still doesn’t mean a lot to me. Let’s take some more data from the same NHTSA table, and see the change from the baseline of not raising fuel economy standards at all. Now we can see the direct climate benefits of these proposals:

|

CO2 concentration (ppm) |

Global mean surface temperature increase (deg C) |

Sea-level rise (cm) |

|||||||||

|

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

2030 |

2060 |

2100 |

|||

| Bush |

.1 |

-.5 |

-1.0 |

-.001 |

-.002 |

-.004 |

0 |

-.02 |

-.04 |

||

| TC=TB (Obama proxy) |

.1 |

-.7 |

-1.6 |

-.001 |

-.003 |

-.007 |

0 |

-.03 |

-.06 |

||

Ah ha! This is useful information. As you can see, the effects are trivially small:

- Both options would reduce the global mean surface temperature by one-thousandth of one degree Celsius by 2030. The Obama option would reduce the global temperature by seven thousandths of a degree Celsius by the end of this century.

- The effects on sea level are too small to measure by 2030. By 2100, the Obama proposal (technically, the TC=TB proxy) would reduce the sea-level rise by six hundredths of a centimeter. That’s 0.6 millimeters.

Hmm. That’s not too much, especially when you consider this is the policy that will affect the #2 source of greenhouse gas emissions in our economy. (#1 is power production.)

In anticipation of some pounding by the climate change crowd:

- These are NHTSA’s calculations using the MAGICC model, not mine. I’m just reporting their results.

- If you have different estimates, I’m happy to consider posting them for comparison. I am less open to arguments about why the MAGICC model is wrong, or why NHTSA’s inputs into that model are wrong. I don’t know the model well enough to debate the points.

Again, the point is not the precise estimates. It’s the order of magnitude. Please don’t tell me this model is flawed. If you disagree with these calculations or this model, give me some numbers you think are better, and that lead to a different conclusion.

Imagine if the President had instead said today, “This new fuel economy and greenhouse gas emissions rule will slow the increase in future global temperature seven thousandths of a degree Celsius by the end of this century, and it means the sea will rise six tenths of a millimeter less than it otherwise would over the same timeframe.” It loses some of its punch, no?

Similarly, when the Supreme Court pushed in Massachusetts v. EPA toward regulating greenhouse gases from new cars and trucks to protect the public health and welfare from “endangerment,” I wonder if they understood that an aggressive proposal would reduce the future sea level increase by 0.6 mm?

6. The national standard = the California standard (roughly).

Technically, the Administration will be setting two standards: one for fuel economy, and another for CO2 emissions from tailpipes. In theory, the two will (basically) match up, hand-waving past a lot of second-order things like flexible fuel vehicle credits and new vehicle air conditioning standards.

During the Bush Administration there was a tussle between California and the federal government. California wanted a waiver to be able to set their own standards for CO2 emissions from cars and light trucks. Another 13 or so States wanted to follow a new California standard. The proposed California standard was significantly more aggressive than anything discussed in Washington.

We argued that having multiple emissions standards would be inefficient. Auto manufacturers would then have either to make cars to meet two different standards, or just dial up the fuel efficiency on all vehicles, so that the California standard would become the de facto national standard.

The President resolved this today by (basically) setting one national standard for fuel economy, and a roughly parallel standard for CO2 tailpipe emissions, that approximate the higher California standard. California is happy that they got their higher numbers. The auto manufacturers avoid the inefficiencies of multiple standards, while having to eat (actually, pass on to customers) the higher costs of making even more fuel efficient vehicles.

7. The auto manufacturers got rolled by the Governator.

The heads of several auto manufacturing firms stood with the President today and smiled. They lost this fight. They pushed incredibly hard during the 2007 legislative battle, and during the subsequent regulatory process, for a fuel economy standard that rose about 2% per year. They dug in hard against a growth rate greater than 3% per year, and told us that 4% per year would destroy them. Our near-final rule averaged about 4.7% per year. The Obama rule averages about 5.8% per year. Either way, this is way, way more than the auto manufacturers wanted.

They had no leverage, of course, and an outcome similar to this was predictable after the November election. So they’re putting the best face they can on it. Interestingly, the press statement from Ford CEO Alan Mulally does not say that he endorses the specific numbers proposed by the President, but instead (emphasis is mine):

Today’s announcement signals the achievement of a crucial milestone – an agreement in principle on a national program for increased fuel economy and reduced greenhouse gases.

This national program will allow us to move forward toward final regulations that all stakeholders can support. We salute the cooperative efforts of the Obama Administration, the state of California, environmental groups and others that played a constructive role in this process.

The framework of the national program will give us greater clarity, certainty and flexibility to achieve the nation’s goals. We will continue to work with the federal agencies to finalize the standards that we are committed to meeting.

Tip for reporters: Ask Ford (and the other manufacturers) if they support the specific numbers proposed by the President today. The statement above is trying to leave Ford wiggle room to argue for smaller numbers in the rulemaking process. If the auto manufacturers wiggle, then you have a repeat of the situation from last week’s health care announcement.

And of course, 1-2 of the U.S. auto manufacturers are now controlled by the U.S. government.

8. Granting the California waiver means California has leverage for next time.

As I understand it, the Administration is technically granting California its EPA waiver, and California has agreed not to invoke it for this process (MY 2011 – MY 2016). Assuming the waiver doesn’t get un-revoked (can it be?) by a future Administration, this means that next time around California will begin the process with the authority to set its own tailpipe emissions standard.

This means that, when we do this again in about five years, California holds all the cards. To quote the Governor in another context (wait for it), “Ill be back.” California will have leverage to set its own standard, which means they can again dictate the national standard. The Obama Administration has moved the primary decision-making locus for future vehicle fuel efficiency rules from Washington DC to Sacramento.

9. In Washington, EPA is now in the driver’s seat, not NHTSA.

The Administration has said there will be two rules. NHTSA will set a fuel economy rule, and EPA will set a tailpipe emissions rule. We know that EPA will always be more aggressive than NHTSA. This means that, to the extent Washington remains involved in future standards (see #8 above), the primary decision-maker becomes EPA rather than NHTSA, since auto manufacturers will have to comply with the more aggressive of the two. NHTSA does not become irrelevant, but the bureaucratic strength is definitely shifting.

This bureaucratic power shift suggests a higher priority will be placed in the future on environmental benefits, and a lower priority on economic costs and safety effects, as we see with today’s proposal.

10. Todays action will accelerate EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from stationary sources.While Congress is futzing around on a climate change bill, EPA is getting ready to bring their “PSD” monster to your community soon.

EPA is in the midst of taking comments on an “endangerment finding” that is a huge deal in the climate change policy world. If the EPA Administrator finds that greenhouse gas emissions from new cars and trucks “endanger public health and welfare,” then it starts a regulatory process. It appears the President is prejudging the result of this regulatory comment process: “the Department of Transportation and EPA will adopt the same rule.”

As a former colleague has taught me, a proposal to regulate greenhouse gases (under section 202 of the Clean Air Act) would greatly accelerate when greenhouse gases become “subject to regulation” under the Clean Air Act. This would trigger ramifications that reach far beyond cars and trucks. As early as this fall, greenhouse gases could become “regulated pollutants” under the Clean Air Act. Once something becomes a “regulated pollutant,” a whole bunch of other parts of the Clean Air Act kick in, and EPA is off to the races in regulating greenhouse gases from a much (much) wider range of sources, including power plants, hospitals, schools, manufacturers, and big stores.

One of the scariest elements of this is called the “Prevention of Significant Deterioration” permitting system. In effect, EPA could insert itself (or your State environmental agency) into most local planning and zoning processes. I will write more about this in the future. It terrifies me.

Thanks for making it to the finish line!