The Bureau of Labor Statistics released the March employment report at 8:30 am. Here is the least you need to know:

- Net payroll employment declined in March by 663,000 jobs.

- That’s a terrible number, and in line with expectations.

- The unemployment rate increased from 8.1% to 8.5%.

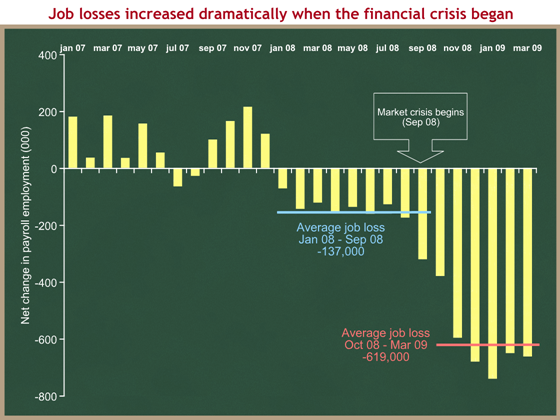

Much of the press coverage talks about “5.1 million jobs lost since the beginning of 2008.” I think that using January 2008 as a start date gives an incomplete and possibly misleading picture. The past fifteen months can be divided into two parts. For the first nine months, the economy was shrinking slightly and employment was declining at a disappointing but not panic-inducing rate. For the last six months, beginning in September as the financial market crisis came to a head, the bottom fell out of the employment market. Take at look at the sudden drop in employment beginning as the market crashes in September. This is the best example that what happens on Wall Street affects what happens on Main Street.

Employment was clearly shrinking in the first 8-9 months of 2008. But the huge employment losses immediately followed the financial crisis. I include September in the first segment because the employment data was collected for that month before the fateful two weeks in the markets. 2008 was a bad economic year, but it’s the fourth quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009 that were disastrous.

This matters because, if the diagnosis is different, then the solutions may be different. If the principal cause of the severity of this recession is the financial crisis, then that would suggest that the most important and urgent element of the solution is to fix the problems in financial institutions and financial markets.

Nobody would or should be happy if the economy were losing 137K jobs per month. But that would be a huge improvement compared to the 600K+ jobs lost over each of the past six months. By the same logic, you use different tools and prioritize different policies if the principal cause of the severe decline in growth and employment is the financial sector trouble. This may sound obvious, but I don’t think it is a given in the Washington policy debate. Everyone says “severe recession,” and then immediately jumps to “huge stimulus” or (“we need a second stimulus”). Fiscal and monetary stimulus can undoubtedly increase GDP growth, but they cannot solve the problems in financial institutions and financial markets.

This is why I try to remind myself to talk about economic problems and a financial crisis. It is also one reason why I am much more concerned about whether the Administration’s new financial policies will work, than whether their spending bill will stimulate GDP growth. In my view, if the financial problems are not fixed, we’re still in trouble almost no matter what else happens. This means I’m in line with Fed Chairman Bernanke, who included a crucial if clause in his March 3rd testimony to the Senate Budget Committee:

Although the near-term outlook for the economy is weak, over time, a number of factors should promote the return of solid gains in economic activity in the context of low and stable inflation. The effectiveness of the policy actions taken by the Federal Reserve, the Treasury, and other government entities in restoring a reasonable degree of financial stability will be critical determinants of the timing and strength of the recovery. If financial conditions improve, the economy will be increasingly supported by fiscal and monetary stimulus, the beneficial effects of the steep decline in energy prices since last summer, and the better alignment of business inventories and final sales, as well as the increased availability of credit.