Each year Congress considers the “defense authorization bill.” This bill gives the U.S. military its legal authorities.

The House passed this bill last Thursday. One provision in the bill would attempt to limit the President’s ability to ignore certain earmarks in the report language that accompanied the bill. This is an important moment in the debate on how to handle earmarks.

I want to focus on those earmarks which are not written into the text of the bill, but are instead included in the report that accompanies the bill. I’m going to delve into the mechanics of earmarking and the current legislative dispute, because the details matter a lot.

As a reminder, we define an “earmark” like this:

(T)he term “earmark” means funds provided by the Congress for projects, programs, or grants where the purported congressional direction (whether in statutory text, report language, or other communication) circumvents otherwise applicable merit-based or competitive allocation processes, or specifies the location or recipient, or otherwise curtails the ability of the executive branch to manage its statutory and constitutional responsibilities pertaining to the funds allocation process.

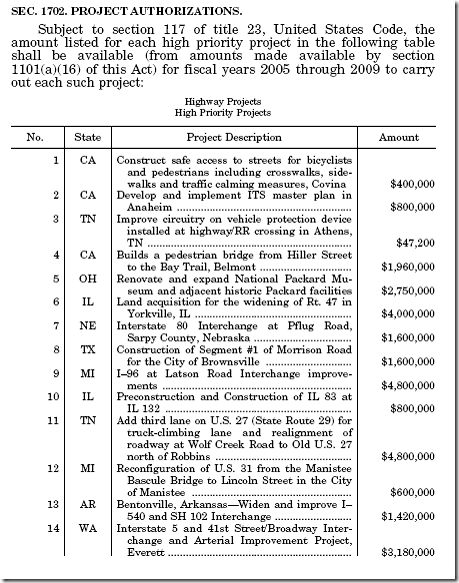

Here is a snapshot of part of a table in the highway law, enacted in 2005. This is an example of a earmark that was in the legislative language of the 2005 highway bill, and is now part of the law.

The full table of “high priority projects” in this highway bill is 197 pages long and contains 5,173 specific line item earmarks. Since they are part of the law, each one is a legal requirement – the Department of Transportation must fund each one.

Now let’s look at the committee report that accompanies the defense authorization bill. It, too, contains earmarks. Here’s one:

Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York

The committee believes that timely infrastructure improvements should be made at Niagara Air Reserve Base and should be provided priority in the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). Therefore, the committee urges the Secretary of the Air Force to accelerate projects, such as the programming to design and construct a small arms range at Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York, in the next FYDP.

Since it’s in report language and not legislative language, this earmark is not legally binding on the Executive Branch. Note the difference in form between a legislated earmark and one in report language:

- legislative earmark – “the amount listed for each high priority project in the following table shall be available …”

- report language earmark – “the committee urges the Secretary of the Air Force to …, such as … at Niagara Air Reserve Base, New York …”

In one case, the law requires the Department of Transportation to spend money in a certain way. In the other, the committee (which is only a subset of one House of Congress) “urges” the Secretary to spend money in a certain way.

As a practical matter, there’s little difference. Agencies typically try to follow these report language earmarks for various reasons, including the fear that if they don’t, the Member of Congress or the powerful Congressional staffer who originated the earmark will come back the next time around and cut their funding. As a result, while report language earmarks are not binding in any formal legal sense, they do affect agency behavior in the real world, and they distort agency spending decisions away from merit-based criteria.

The other important thing to understand about report language earmarks is that, if you work in Congress, they are relatively easy to get done. It’s pretty hard to change a spending bill as it moves through the legislative process, but it’s not that hard to get an earmark into a report. Reports are written by Congressional staff, and are never voted on or amended by Members.

Here is what the President said in the State of the Union address last year:

Next, there is the matter of earmarks. These special interest items are often slipped into bills at the last hour — when not even C-SPAN is watching. (Laughter.) In 2005 alone, the number of earmarks grew to over 13,000 and totaled nearly $18 billion. Even worse, over 90 percent of earmarks never make it to the floor of the House and Senate — they are dropped into committee reports that are not even part of the bill that arrives on my desk. You didn’t vote them into law. I didn’t sign them into law. Yet, they’re treated as if they have the force of law. The time has come to end this practice. So let us work together to reform the budget process, expose every earmark to the light of day and to a vote in Congress, and cut the number and cost of earmarks at least in half by the end of this session. (Applause.)

You’ll note that there are three components to the President’s 2007 earmark challenge:

- cut the number of earmarks in half;

- cut the cost of earmarks in half; and

- end the practice of earmarking in committee reports.

Here is what he said in the State of the Union address this year.

The people’s trust in their government is undermined by congressional earmarks — special interest projects that are often snuck in at the last minute, without discussion or debate. Last year, I asked you to voluntarily cut the number and cost of earmarks in half. I also asked you to stop slipping earmarks into committee reports that never even come to a vote. Unfortunately, neither goal was met. So this time, if you send me an appropriations bill that does not cut the number and cost of earmarks in half, I’ll send it back to you with my veto. (Applause.)

Then, on January 29th, the President signed an Executive Order (E.O. 13457), which included the following text:

(T)he head of each agency shall take all necessary steps to ensure that:

(i) agency decisions to commit, obligate, or expend funds for any earmark are based on the text of laws, and in particular, are not based on language in any report of a committee of Congress, joint explanatory statement of a committee of conference of the Congress, statement of managers concerning a bill in the Congress, or any other non-statutory statement or indication of views of the Congress, or a House, committee, Member, officer, or staff thereof;

The President therefore used this Executive Order to direct agencies to follow the law, but to ignore earmarks that are not in the law, those in report language. He instead told them to use “merit-based criteria” as the basis for determining how to spend. He has the right to do so, since report language is advisory and not legally binding.

Now let’s move to the new legislative issue. The defense authorization bill passed by the House last Friday contains a provision that tries to nullify this Executive Order, and to force the Executive Branch to follow earmarks in report language. Here’s the provision from the bill:

SEC. 1431. INAPPLICABILITY OF EXECUTIVE ORDER 13457.

Executive Order 13457, and any successor to that Executive Order, shall not apply to this Act or to the Joint Explanatory Statement submitted by the Committee of Conference for the conference report to accompany this Act or to H. Rept. XXX or S. Rept. XXX.

This is Constitutionally objectionable. Here are some questions raised by this language:

- How can a bill limit “any successor executive order,” when such does not yet exist?

- Does this section infringe on the President’s Constitutional authority to supervise the Executive Branch as he see fit?

- How can Congress prevent the President from directing agency heads to ignore something that is not in the law? (This one is my favorite.)

This section of the bill was debated on the House floor, but the House majority leadership used the Rules Committee to preclude consideration of an anti-earmark amendment by Rep. Flake (R-AZ). This amendment would have stricken section 1431 from the bill. Mr. Flake’s amendment would have been an excellent opportunity for Congress to take a significant procedural step toward reducing the number of earmarks, and toward forcing earmarks to be considered in the light of day on the House and Senate floors, rather than being hidden in committee reports.

Here is the relevant text on section 1431 from our Statement of Administration Policy (SAP). As you can see, this provision merited a veto threat.

If the final bill presented to the President contains any of the following provisions, the President’s senior advisors would recommend that he veto the bill.

…

Earmark Reform: The Administration strongly opposes the bill’s provisions to block the President’s recent Executive Order 13457, “Protecting American Taxpayers from Government Spending on Wasteful Earmarks.” This Executive Order made clear that future earmarks would be honored only if included in the text of legislation, building on the President’s pledge in his State of the Union address to veto FY 2009 spending bills that do not cut the number and cost of earmarks in half from FY 2008 levels. The President took this unprecedented action on earmarks to bring more transparency and accountability to the budget process – just as the American people expect and deserve. The President’s goal is to reform the earmarking culture that often slips earmarks into bills at the last minute, without discussion or debate – which contributes to the wasteful and excessive pork-barrel spending the Administration has seen in recent years. Section 1431 of the bill is also constitutionally objectionable in that it seeks to prohibit the President from supervising Executive Branch agencies as to discretionary matters and to have agencies implement informal preferences of Congressional committees that are not enacted into law.” Moreover, while Executive Order 13457’s objectives could still be accomplished by other means, this bill would cause confusion among agencies, inefficient use of resources, and unnecessary litigation potential.

The President is committed to “expos[ing] every earmark to the light of day and to a vote in Congress, and cut[ting] the number and cost of earmarks at least in half.” And he has issued veto threats to back that up. We’ll see whether Congress meets that standard.