Should taxpayers subsidize Chrysler retiree pensions or health care?

The Administration’s negotiations with Chrysler and their stakeholders have a Thursday deadline. Friday’s Wall Street Journal reported a rumor:

Chrysler and the UAW agreed in 2007 that the auto maker would put $10.3 billion into a union-managed retiree healthcare fund. Half of that would now be paid in equity, with the rest coming over time in cash, either from Chrysler or the U.S. Treasury Department, according to people familiar with the talks.

… Even less clear is what will happen on the pension front. Chrysler’s pension is under-funded to the tune of about $9.3 billion, according to an estimate by the government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. But it’s unlikely Fiat would agree to take on those obligations as part of any alliance.

It seems compassionate to help Chrysler retirees by having taxpayers subsidize these unfunded promises made by their employer. Doing so would also help facilitate a Chrysler/Fiat deal. There are two significant long-term costs to such an action. It would set an expensive precedent for taxpayers, and it would harm future retirees of other firms. Using taxpayer funds to help Chrysler retirees now would create a perverse incentive for management and labor leaders of other firms to behave even more irresponsibly than they have in the past, by jointly agreeing to underfund future pension and retiree health promises.

Defined benefit pension plans claim to guarantee workers a specific benefit when they retire, but that promise is good only if it is fully funded. If a firm with a defined benefit pension plan goes bankrupt and if the plan is underfunded, then a government-run corporation called the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) covers some of the losses:

- Start by paying benefits up to a ceiling defined by PBGC ($54,000 per year in 2009 for a 65-year old).

- If you have money left over, keep paying benefits up to the amounts promised to retirees.

- If you run out of money before paying everyone’s benefit, then PBGC will fill up the remaining gap, but only up to the ceiling. Above the ceiling, workers lose their pensions.

So if you are a retiree with a promised $40K annual pension, you will get the full amount. If you were promised $80K and the fund runs out at $50K, then the PBGC will top you off to $54K. You lose the remaining $26K.

PBGC is designed to be self-sustaining: premiums paid by insured firms are supposed to cover expected PBGC losses as it pays benefits to workers of bankrupt firms with underfunded pensions. Taxpayers do not subsidize these benefits (yet).

PBGC insurance creates a moral hazard that encourages management and labor leaders to underfund their pension promises. The negotiators maximize the amount of current compensation, and they negotiate greater pension or retiree health benefits, but the firm doesn’t fully fund those new promises. Both sides agree to make overly optimistic assumptions about the investment returns on the funds. This results in unfunded promises to future retirees. You end up with a situation like Chrysler: management and labor leaders left the plan $9.3 billion short, and the government has insured only $2 billion of that amount.Chrysler retirees will lose the other $7.3 billion. Both Chrysler management and UAW’s leaders are jointly to blame for shafting Chrysler retirees.

Dr. Zvi Bodie describes a long-term risk now facing taxpayers and the Administration:

“If one of these companies solves its pension problem by shunting it off to the federal government, then for competitive reasons the others have to do the same thing,” said Zvi Bodie

I assume that Administration negotiators are being pressured fiercely by UAW to pay these unfunded promises. UAW has a huge long-term incentive to set the precedent that can apply to parallel situations.

The long-run problem has a simple solution: firms must fully fund their promises. We could tighten the rules so that as a condition of receiving PBGC insurance firms (1) must fully fund their pension promises, (2) may not make new promises until the old ones are funded, and (3) must make transparent and realistic assumptions about investment returns.

These were the principles that President Bush pushed for when Congress changed the PBGC laws a few years ago. We made headway but were far from completely successful. There were a few responsible Members: House Leader Boehner (R), Senator Grassley (R), and Senator Baucus (D) were strong, but they were outnumbered. Management (especially of the airlines) lobbied Republican members, while labor unions lobbied Democrats. We were forced to compromise by this political alliance at the expense of taxpayers and future retirees.

The President’s negotiators appear to be in a tough spot. I hope they recognize the long-term harm they could do to future retirees and taxpayers if they set a bad precedent this week.

Will House Democrats get BTU’d on climate change?

A House vote in 1993 laid the groundwork for an important upcoming House vote on climate change legislation.

In 1993 then-Vice President Gore led the Clinton Administration to propose increasing the taxation of energy. Called the “BTU tax,” the Administration proposed to tax the energy content of a fuel source, measured in British Thermal Units (BTUs).

Democrats were in the majority, and 218 of them voted for the bill containing the BTU tax. 38 House Democrats and all 175 House Republicans voted no.

The three vote margin of victory suggests that House Democratic leaders had to twist the arms of reluctant Democrat Members to vote aye. In this scenario, if you are a House Democrat who does not have a strong view on the substance but is nervous about the politics of voting for higher energy taxes, you would like the bill to pass (so that your leaders get what they want and stop pressuring you) without your vote (so that you don’t give your opponent back home an effective line of attack).

The Senate Democrats, who were in the majority, promptly dropped the BTU tax without a vote. They also made it clear they would not accept a BTU tax in the final conference report on the bill.

Those nervous House Democrats who had voted for the bill with the BTU tax had the worst of all worlds. They had cast a costly political vote for no policy benefit.

A phrase soon entered the legislative vernacular. Senate Democrats had “BTUd” House Democrats.

Fast forward to 2009.

The House is considering climate change legislation authored by a key subcommittee chairman, Rep. Ed Markey (D-MA). House Republicans, along with important Democrats like Rep. John Dingell (D-MI), are vigorously opposing the bill, calling it a “cap-and-tax” bill that would raise energy costs.

All indications from the Senate are that legislation similar to the Markey bill is extremely unlikely to pass the Senate this year.Two important votes in the Senate budget resolution debate sent incredibly strong signals about the Senate’s intentions:

- 67 Senators, including 26 Democrats, voted against creating fast-track reconciliation protections for a cap-and-trade bill, meaning that supporters would need 60 votes to pass a bill, rather than 51.

- 54 Senators, including 13 Democrats, voted for an amendment that would allow any Senator to initiate a vote to block any climate change provision which “cause[s] significant job loss in manufacturing or coal-dependent U.S. regions such as the Midwest, Great Plains, or South.”

These votes suggest that there is not even a working majority in the Senate for an aggressive cap-and-trade bill. When an actual bill with measurable and visible costs is debated, I expect Senate support to be even weaker.

The conventional wisdom is that Speaker Pelosi will make the House vote on a version of the Markey bill. With 254 House Democrats, she has a wide margin (36 votes) to ensure passage, but she could easily have important House Democrats like Mr. Dingell making a similar case as House Republicans, that the bill should be opposed because of the higher energy costs for consumers.

Imagine that you are a House Democrat from a conservative, manufacturing-heavy, or coal-heavy district. Whether or not you privately agree with the substance of the bill, and no matter what your view is on the importance of climate change, you will be asked to cast a politically risky vote for a bill that looks certain not to make it to the President’s desk.

You might say to your leadership, “I am more than willing to vote for this bill if you tell me that we can get the policy benefit of a signed law.” But if the Senate is going to BTU us again, why should I have to take a political risk?”

A cap-and-trade bill is highly unlikely to make it to the President’s desk this year. Even so, this year’s votes will set the terms of debate for future legislative efforts, when there might be a higher probability of legislative success.

Should bank stress test results be public?

Today the 19 largest banks are getting the results of their stress tests from their regulators. Should these results be made public?

This is not a simple question.

The big upside is that markets will have more information, and that all market participants will have access to the same information. This can allow investors, counterparties, and customers to evaluate the health and stability of the banks with which they are doing business. I have a default presumption that more information more widely disseminated is a good thing.

Downside 1: Some banks might be just above the bubble but rank low. They may still be healthy enough to survive and eventually succeed, but if they are disclosed to be among the weakest, that disclosure may cause a run of depositors, counterparties, or investors. This could push some marginal banks over the edge and cause them to fail.

This is not a trivial concern. Last September there were reports that investors were “testing” even the clearly healthiest investment banks (JPM Chase, Goldman Sachs) shortly after Lehman’s fall. Senior policymakers remember that vividly, when panic might have destroyed banks that on paper were solid. From the perspective of the policymakers who have the information, it is easy to understand why they may be highly risk averse. From their perspective, not disclosing the information may appear to be the safer course.

There is a response to this downside. Banks that do well in the stress tests have an incentive to let the world know that. It may be hopeless for policymakers to think they can protect the weaker banks by not having the government release the information, because the strong banks will do it implicitly by shouting their good news.

Downside 2: The stress tests might not be well-designed. If they are poorly designed, overly optimistic, or just misinterpreted by the market, then the government could be injecting bad information into the market. Government may not be smart enough to design the tests to provide enough useful information to the markets.

More importantly, any stress test is highly imperfect, and there is a risk that the results would create a sense of false certainty. I read a lot of market commentary while working in the White House, and was amazed at how frequently high-level market commentaries completely misinterpreted or misread data that we released (much less policy statements).

This is a close call, and people whom I respect advise in different directions. I fall back on my default presumption / instinct, which is to release the information. There is a small probability of a really bad outcome (a panic/run), and a much larger probability of a good outcome with no run and somewhat better informed markets. I also think it is easy for policymakers to overestimate the amount of control they have over the situation.

The Wall Street Journal reports the following game plan:

- Today the regulators are giving results to the banks privately, and asking them not to disclose them. They are also releasing the test methodology.

- 10 days from now, the regulators will release results of the stress tests, although “regulators also have not decided how much information will be disclosed May 4.”

On the whole, this game plan makes sense to me. I am not sure they will be able to hold out for 10 days, and my instinct is that they should release more information rather than less. I hope market participants will take the time to understand just how imperfect this information will be.

By the way, I presume that the decision to leak that they expect to release the results was made after they knew the results of the tests. This suggests that the results are generally good. If the stress tests showed that half of the banks would fail, I presume they would not be signaling a future release.

Will the Administration fund CSI: New Haven and Tattoo removal in L.A.?

President Obama may not realize that the people who work for him are required to ignore hundreds (thousands?) of Congressional earmarks. The President has the ability to stop them from doing so. I hope that he will not.

Thanks go to former OMB General Counsel Jeff Rosen for pointing this out.

An Executive Order is a document signed by the President that establishes how he organizes and manages the Executive Branch. This power is derived from the first sentence of Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution: “The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

Some Executive Orders are time limited. Others remain in place until they are modified or repealed. Executive Orders span Presidential terms, so any Executive Order issued before President Obama’s term began that has not yet “sunset” is still legally binding upon the Executive Branch. President Obama can unilaterally modify or repeal such an E.O., but until he does, Executive Branch employees are legally required to continue implementing it.

On January 29, 2008, President Bush signed Executive Order 13457, “Protecting American Taxpayers From Government Spending on Wasteful Earmarks.” This E.O. has no sunset date. It continues to be legally binding until modified or repealed by our current President.

On March 11, President Obama publicly stated his own principles on earmarks, but he has not modified or or repealed E.O. 13457.

Let us therefore look at the current policy of the Executive Branch regarding implementation of earmarks. I have seen no public indication that anyone in the Executive Branch is following these requirements, or is even aware of them. Here is the key language from the Executive Order.

Section 1 – For appropriations laws and other legislation enacted after the date of this order, executive agencies should not commit, obligate, or expend funds on the basis of earmarks included in any non-statutory source, including requests in reports of committees of the Congress or other congressional documents, or communications from or on behalf of Members of Congress, or any other non-statutory source, except when required by law or when an agency has itself determined a project, program, activity, grant, or other transaction to have merit under statutory criteria or other merit-based decisionmaking.

Section 2 implements this requirement by requiring “Agency Heads” (Cabinet Secretaries and others who run sections of the government) to do certain things. The language is easy to understand:

Section 2. Duties of Agency Heads. (a) With respect to all appropriations laws and other legislation enacted after the date of this order, the head of each agency shall take all necessary steps to ensure that:

(i) agency decisions to … expend funds for any earmark are based on the text of laws, and in particular, are not based on language in any report of a committee of Congress …

(ii) agency decisions to … expend funds for any earmark are based on authorized, transparent, statutory criteria and merit-based decision making

(iii) no oral or written communications concerning earmarks shall super-sede statutory criteria, competitive awards, or merit-based decisionmaking.

This language is formally telling Executive Branch employees “If an earmark is not in the law, you must ignore it.” Use your merit-based decisionmaking process, even if the committee report that accompanies the bill says “we think you should spend money on project X,” and even if you get a phone call from a Member of Congress or Congressional staffer.

As a reminder, we define an “earmark” like this:

(T)he term “earmark” means funds provided by the Congress for projects, programs, or grants where the purported congressional direction (whether in statutory text, report language, or other communication) circumvents otherwise applicable merit-based or competitive allocation processes, or specifies the location or recipient, or otherwise curtails the ability of the executive branch to manage its statutory and constitutional responsibilities pertaining to the funds allocation process.

Let’s look at the report that accompanied the omnibus appropriations bill that President Obama signed into law on March 11. Here are four earmarks from the committee report.

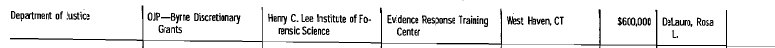

The first is by Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT). It’s $600,000 of “Byrne Discretionary Grants” from the Department to Justice support an Evidence Response Training Center at the Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science in West Haven, CT. You can find it on page 268 here.

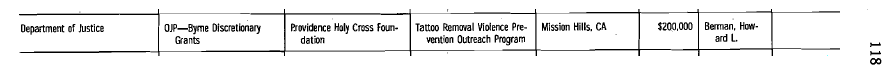

Here is another, by Rep. Howard Berman (D-CA). It’s $200,000 of Byrne Grants for a Tattoo Removal Violence Prevention Outreach Program at the Providence Holy Cross Foundation in Mission Hills, CA. You can find it on page 283 here.

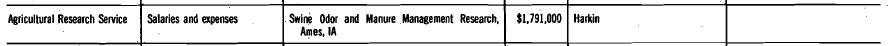

We also have $1.791 M for Swine Odor and Manure Management Research at Ames, IA, sponsored by Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA).you can find it on page 77 here.

We also have $1.791 M for Swine Odor and Manure Management Research at Ames, IA, sponsored by Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA).you can find it on page 77 here.

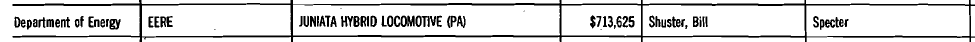

To show that this is bipartisan behavior, here is one from Rep. Bill Shuster (R-PA) and Sen. Arlen Specter (R-PA) for $713,625 for the Juniata Hybrid Locomotive. You can find it on page 263 here.

Although all four of these earmarks are in the report language, they have different legal statuses. The first two are pure report language earmarks. There is nothing legally binding about them, and they are therefore subject to E.O. 13456. The third and fourth (swine odor research and the hybrid locomotive) are “incorporated by reference” into the law, so the Executive Branch would be breaking the law if they tried to ignore them. I will write about incorporation by reference in the future.

Now according to E.O. 13456, Attorney General Eric Holder, as the “Agency Head” for the Justice Department, has been directed to not allocate of Byrne Discretionary Grant funds based on the inclusion in the conference report of the earmarks for CSI: West Haven or Mission Hills tattoo removal. That does not mean that those institutions may not be funded. It means that if they are funded, DoJ must determine that they deserve funds “based on authorized, transparent, statutory criteria and merit-based decisionmaking.” And DOJ is not permitted to allow a phone call from Mrs. DeLauro or her staff, or from Mr. Berman or his staff, to supercede those criteria.

The process point is important in earmark reform. There are certain earmark recipients that could win funding in a competitive or merit-based decision making process. Relying on such a process ensures that funds will be allocated on merit rather than political power.

One of two scenarios can now play out. I will rank them in my order of preference:

- The Executive Order stays in place and unmodified. Budget Director Orszag issues an implementation memo parallel to the one issued by Director Nussle last October on the FY 09 continuing resolution. Throughout the Executive Branch, Agency employees are required to ignore earmarks that are not in the law.

- The President repeals or modifies E.O. 13456.

If the first scenario plays out, I will heartily congratulate the President for being as strong as he says he is on earmark reform.

If the second scenario plays out, then the President will have weakened the earmark rules put in place and implemented by his predecessor.

If the Executive Order is not modified and no apparent action is taking place to comply with it, then I believe Agency Inspector Generals have an obligation to make certain that the E.O. is being implemented within their respective agencies.

The President said on March 11,

I ran for President pledging to change the way business is done in Washington and build a government that works for the people by opening it up to the people. We eliminated anonymous earmarks and created new measures of transparency in the process.

All the President has to do now to change earmarking for the better is make certain this Executive Order is enforced.

Apparently $634 B is only the down payment for health care reform

I had missed this from the President’s remarks to Congress on February 24th:

This budget builds on these reforms. It includes a historic commitment to comprehensive health care reform – a down-payment on the principle that we must have quality, affordable health care for every American.

Budget Director Peter Orszag repeated the “down payment” language on his blog Monday, and was slightly more specific:

And in the President’s budget, we make a historic down payment on fundamental health care reform – a commitment also embodied in the budget resolutions passed in Congress.

This clearly suggests that the Administration thinks that the $634 B “reserved” over the next ten years in the President’s budget (table S-6) will not suffice to fulfill “the principle that we must have quality, affordable health care for every American.” By combining and repeating the “down payment” language with the “every American” language, they are covering themselves for later as they now create a political commitment that exceeds their budgetary commitment.

There are two other details to the President’s language that are interesting, and that he has repeated several times since the February address:

- He says all Americans should have “health care” rather than “health insurance.” This allows him wiggle room to accept a solution that does not provide universal pre-paid health insurance coverage for every American. This mitigates my down payment point somewhat, but only if the Congress decides to go for less than universal coverage. I would lay extremely high odds that before this speech there was a West Wing debate about whether the President should say “health care” or “health insurance,” with the Lefties arguing for “insurance” and getting overruled to allow flexibility to later define a win with legislation that provides something less than universal coverage.

- He consistently says “quality health care” or “high-quality health care.” That is more expensive than “basic health care,” and opens the question about who defines “high quality,” as well as the government-mandated benefits problem.

The growth of federal health care spending is one of our top two short-term and long-term budgetary problems. The President’s budget commits to making that problem worse by creating a new promise, only partially funding that promise, and then not specifying policies that will produce the long-term savings for which the Administration wants to claim credit. I am stunned that the White House staff let the President say this without the policies and numbers to back it up:

It’s a commitment that’s paid for in part by efficiencies in our system that are long overdue. And it’s a step we must take if we hope to bring down our deficit in the years to come.

I am not disappointed but not surprised that the press corps has not called the Administration to back this claim up. I can find no evidence of policies that will produce “efficiencies in our system,” or that will “bring down our deficit in the years to come.” As CBO wrote in December, better information and research alone will not achieve those goals.

CBO: Health IT and preventive care won’t save a lot of money

It looks like my post from yesterday agrees with CBO’s December paper. Maybe I should have read it earlier.

Yesterday I wrote,

Information must be combined with the incentive to purchase high-value medical care … a decision that involves both the medical benefit of the treatment and the financial cost.

The Administration’s proposals on health information technology, electronic medical records, and medical outcomes research may improve health, but they will have little effect on slowing the growth of health care spending for those with low-deductible, low-copayment private health insurance.

The Administration is giving an incomplete answer. They need to explain not just how much they will spend on health information technology, electronic medical records, and medical outcomes research, but how that information will be used to reduce cost growth, and by whom.

In December the Congressional Budget Office wrote,

Other approaches – such as the wider adoption of health information technology or greater use of preventive medical care – could improve people’s health but would probably generate either modest reductions in the overall costs of health care or increases in such spending within a 10-year budgetary time frame.

In many cases, the current health care system does not give doctors, hospitals, and other providers of health care incentives to control costs. Significantly reducing the level or slowing the growth of health care spending would require substantial changes in those incentives.

I am glad that I am in the same place as CBO on this point. Please consider this an ex-post footnote to yesterday’s post.

CBO: More taxpayer-financed health insurance coverage won’t save money

Last December the Congressional Budget Office published a comprehensive paper that describes how they approach analysis of health insurance reform proposals. It is a critically important (and somewhat technical) document for anyone who cares about health care legislation in the United States.

CBO is the referee for the budgetary costs of legislation. They estimate the effects on the federal budget of a bill or amendment, and those estimates are then inputs into legislative processes that determine what bills and amendments can and cannot be considered. In the Senate, for instance, there are many cases where an amendment can pass with a majority (51 votes) if any spending increase is offset by an equal-sized or greater spending cut, but for which you would need 60 votes if that spending increase is not fully offset.

Like a referee, CBO gets screamed at a lot by the coaches and players (Members of Congress and their staffs). Like a referee, their judgment calls (estimates) matter. And like a referee, what CBO says goes. It does not matter whether the player’s foot was or was not on the three-point line. What matters is what the referee says about whether or not his foot was on the line.

This study is a bit like a referee giving an interview before the big game, and explaining his philosophy toward refereeing certain aspects of the game. Smart coaches and players will adjust their strategies based on this information. At a minimum, it gives the spectators insight into what to expect as the big game approaches.

Here is one interesting thing that pops out from the Executive Summary of the report:

These problems [rising costs of health care and health insurance, and the number of uninsured] cannot be solved without making major changes in the financing or provision of health insurance and health care. In considering such changes, policymakers face difficult trade-offs between the objectives of expanding insurance coverage and controlling both federal and total costs for health care. (page ix)

They key phrase is “difficult trade-offs between.” CBO is clearly rejecting the argument made by some advocates of universal coverage, that covering more people will reduce federal spending. CBO is saying simply that if you want taxpayers to finance more health insurance coverage, then both federal and total health care spending will go up.

Interestingly, while I hear the counter-claim frequently from some on the Left (more coverage will reduce unreimbursed emergency room and clinic care, leading to a net savings to the taxpayer), I have never heard it from the Administration. The logic implicit in the Administration’s argument is not that “Universal coverage will pay for itself.”

It appears that the Administration’s logic is instead, “Yes, covering more people through taxpayer-financed program expansions will cost more, but we will more than offset those higher costs through other long-term reforms.” As I explained yesterday, they have yet to specify those cost-saving policy reforms.

Expanding taxpayer-financed health insurance coverage will cost taxpayers more, and will dramatically worsen our short-term and long-term budgetary problems. This is CBO’s “difficult trade-off.” Policymakers must either choose which problem they want to solve, or they must find so much savings through other reforms that they can more than offset the higher expenditures from the proposed new spending program.

This may seem like a trivial conclusion, but it is non-trivial in the legislative debate, and should have an important effect on legislation. The referee has spoken.

Slowing health cost growth requires information AND incentives

When I was growing up, I was taught that you change the oil in your car every 3,000 miles.

Suppose I take my three-year old car to Jiffy Lube for an oil change.

Jiffy Lube has all the latest information technology, as well as good data on both manufacturers’ recommendations and best practices.

After entering my license plate into their database and checking my odometer, the technician says, “Mr. Hennessey, it’s been only 3,000 miles since your last oil change. Your manufacturer recommends an oil change once every 12,000 miles. We have even better data based on comparing wear and tear on vehicles from all over the country, and we recommend once every 10,000 miles. Still, you have at least 7,000 miles to go before you need to change your oil.”

I argue, “But I thought you were supposed to change your oil every 3,000 miles?”

He replies, “Those were the old practices. We have better diagnostic technologies, better engines, and better oil. It’s now every 10,000 – 12,000 miles.”

I respond, “Thanks. How much does an oil change cost?”

Imagine if the technician were to say, “$50, but your insurance covers it. You only have to pay a $5 deductible.”

What would you do?

The President is absolutely right when he says, “We can’t allow the costs of health care to continue strangling our economy.”

The President’s budget director, Peter Orszag, is the lead Administration advocate for this policy. Director Orszag is right when he writes on his blog,

Now, many of you have heard me go on about how important it is to reform health care in order to bend the curve on long-term costs and get our nation on firmer fiscal footing … and this data shows how critical that effort is. When we say that health care is consuming too much of our GDP, we are not just citing an abstract statistic. These costs have real implications in sectors across our economy, limit our economic growth, reduce opportunities, and harden inequalities.

He then, however, argues,

This is why the Administration is making historic investments through the Recovery Act in efforts that will be crucial in bending the curve on the growth of health care costs while improving the health outcomes we can expect from our medical system. We are investing over $19 billion in health information technology to help computerize Americans’ health records, which will reduce medical errors and enhance the array of data that physicians and researchers have at their disposal. We are investing $1.1 billion in comparative effectiveness research, which will yield better understandings of which medical treatments work and which do not.

Additional information is good, but the example above shows why information by itself will not significantly slow the growth of medical care spending. Information must be combined with the incentive to purchase high-value medical care – a decision that involves both the medical benefit of the treatment and the financial cost. The government could use this information to reduce costs in health programs that it runs, like Medicare and Medicaid (I am certainly not endorsing that). But those of us with private health insurance are largely protected from the costs of the medical care we use because of the general prevalence of low deductibles and copayments. Even if we have better information, we may not care if the benefit of a particular medical treatment is small, as long as it seems really inexpensive. The Administration’s proposals on health information technology, electronic medical records, and medical outcomes research may improve health, but they will have little effect on slowing the growth of health care spending for those with low-deductible, low-copayment private health insurance.

I favor helping individuals get information so they can decide what is high-value for them. I imagine that those who favor a single-payor system would say those tradeoffs should be made for everyone by the government.

The Administration is giving an incomplete answer. They need to explain not just how much they will spend on health information technology, electronic medical records, and medical outcomes research, but how that information will be used to reduce cost growth, and by whom.

To be able to credibly claim that they will slow the growth of health spending, the Administration needs to answer the following questions:

- Who will be empowered to make decisions based on this improved information?

- Upon what basis will that decision-maker compare the costs and benefits of a particular medical treatment, good, or service?

- How will you change policy to create incentives for that decision-maker to choose high value medical care?

Until they provide answers, they cannot legitimately claim to be slowing the growth of health spending in the private sector.They are just increasing government spending on technology.

Jim Capretta has discussed this in greater detail on his excellent blog, Diagnosis.

Baseline games

Suppose I bought an iPhone yesterday for $500.

Suppose I argue that I will save $2000 this week, because I intend to refraining from buying an additional iPhone today, nor will I buy one this Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday.

Suppose I plan to buy a new flat screen TV tomorrow for $1500.

Can I claim I that have paid for my TV by cutting other spending, and that in addition I will be saving $500 this week?

This is what the Administration has done with war costs in their budget.

There is no debate about how much I will spend this week: $500 for the iPhone, plus $1500 for the TV, equals $2000 of total spending.

The question is instead whether I have increased or decreased my spending compared to what it otherwise would have been.

In this example, I argued that I will cut my total projected spending by $500, and I am also paying for the TV by cutting spending.

You argue that it is absurd to assume that I would buy an iPhone each day this week. The right baseline, you argue, is to treat the iPhone purchase as a one-time expenditure, and to use a spending baseline of zero for the remainder of this week. Thus the $1500 TV purchase is a spending increase, not a spending cut.

The argument about whether the President’s budget increases or cuts the deficit is therefore a debate about the baseline – what would happen otherwise?

Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) did a good analysis of the war spending assumption in the President’s budget. He and his staff conclude that the President’s budget includes $1.5 trillion of phony savings (over 10 years) by inflating the war spending baseline the way I did with my mythical cancelled iPhone purchases. The President’s budget makes a similar $330 B assumption for Medicare payments to doctors.

Even more intriguing, the President’s budget (table S-5 in this document) argues that the $9 trillion of incremental baseline debt they argue they “inherited” should include $835 B of additional debt resulting from two laws President Obama signed: the stimulus law, and the omnibus appropriations law. Clearly that $835 B of additional debt was not inherited, and should be netted out against their claimed future deficit reduction.

Here is the math behind the Administration’s claim of fiscal responsibility, and CBO’s countervailing analysis. All figures are for the next ten years (2010-2019):

| Administration | CBO | |

| Additional debt under the baseline | $9.0 trillion | $4.5 trillion |

| Additional debt under the President’s budget | $7.0 trillion | $9.3 trillion |

| Effect of the President’s budget on additional debt | -$2.0 trillion of debt | +$4.8 trillion of debt |

Let us walk through this step by step.

- The Administration has a radically different starting point than CBO. The President’s budget starts by assuming that $9.0 trillion of debt will be accumulated over the next ten years if the President’s budget is not enacted. The Congressional Budget Office assumes that $4.5 trillion of debt will be accumulated over the next ten years in the same scenario.

- The Administration assumes that its policies will result in $7 trillion of additional debt added over the next decade. That is $2.3 trillion less than CBO assumes. We saw why yesterday – the President’s budget assumes that the economy will grow faster than CBO assumes. This faster economic growth assumption would result in faster revenue growth for the government, and therefore smaller (but still huge) budget deficits.

- These two differences in assumptions result in two completely different views of the President’s budget. The President and his advisors argue they are being responsible by reducing the deficit by $2 trillion over the next decade, while someone relying on CBO’s numbers would say the President’s budget is horribly irresponsible and that it increases the debt by $4.8 trillion more than it would otherwise be.

This debate about whether the sign is a + or a – is politically significant. The -$2 trillion figure is the cornerstone of the Administration’s claim to fiscal responsibility. It allows them to justify big spending increases like the $600+ B new health entitlement.

At the same time, we should not let this important debate obscure that, even using the Administration’s more optimistic numbers, the President’s budget would mean that debt held by the public will increase by $7 trillion over the next decade, to a share of the economy not seen since the end of World War II.

Even if you believe the Administration’s deficit reduction claim (I do not), it is nowhere nearly enough deficit reduction. We need either to dramatically slow spending growth, or raise taxes, or some combination of the two. I support doing it all on the spending side while keeping taxes from increasing. Your view may differ. But we cannot accumulate $7 to $9.3 trillion more debt over the next decade and claim that we are being fiscally responsible.

The danger of autopilot entitlement spending

Each year Congress enacts 12 annual appropriations (spending) bills. Those bills are the subject of vigorous and legitimate fights about spending priorities.

Included in these annual appropriations bills are spending for defense, veterans, military construction, highways, housing, education (except student loans), foreign aid and the foreign service, the FBI, CIA, and Department of Justice, most of the Departments of Commerce and Labor, Congress and the White House, the Department of Homeland Security, including Border Patrol and Customs, highways, airports, and ports, health and energy research, scientific grants to universities, the Interior Department and Environmental Protection Agency budgets, national parks, … you get the idea.

Much of what we think of as the federal government gets its funding annually through these 12 bills. As a result, these debates and tradeoffs occur each year. This is called “discretionary” spending, which goes through the “annual appropriations process.”

In contrast, several “mandatory spending programs,” aka “entitlements” are on autopilot. Spending occurs based on formulas written in law. Those formulas contain variables that change according to external factors (wages, inflation, food costs, health care costs). Most importantly, these programs are on autopilot. Spending continues from one year to the next according to these formulas unless the laws are changed.

If Congress does not enact an annual appropriations bill this year for the Department of Justice, then DOJ will have to shut down on October 1st.

If Congress does not enact a law this year affecting Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid, those programs will continue spending money based on the automatic formulas within them.

There are many smaller entitlements other than the big three (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid), but in an aggregate budget sense, it’s the big three that matter most. Payments to federal retirees and the refundable elements of tax credits are the next biggest.

From an aggregate budgetary perspective, these big three programs are (i) huge, and (ii) growing faster than the economy. As a result, they are swallowing up the rest of the budget, and they are the principal source of future spending growth.

These automatic spending increases that are “built into the baseline” are not carefully reexamined each year, and are not forced to compete with other priorities. The national parks, scientific research, and defense budgets are at a tremendous disadvantage – each year they have to compete for the marginal spending increase dollar, while the Big 3 entitlements quietly grow without anyone really noticing too much.

Let’s look at some numbers.

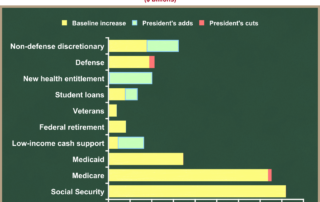

If the President’s budget were to be enacted in full, four areas of spending would increase dramatically over the next ten years.

- The new health entitlement would go increase $100 B per year in 2019 (starting from nothing now).

- Non-defense discretionary spending would increase $74 B from this year to 2019.

- A collection of low-income cash support and food stamps programs would increase $61 B from this year to 2019.

- Federal spending on student loans would increase $29 B from this year to 2019.

Importantly, these are proposed policy changes from the default baseline. Now let’s look at a picture and see where the increased spending would go. This graph shows increases in spending, comparing 2019 under the President’s budget to spending this year. To be clear, this graph shows the level of projected spending in 2019, minus the level projected for this year (2009). The amounts on this graph are increases above where we are now, measured in billions of dollars.

The green bars show the President’s big spending increase proposals. You can see the big new health entitlement, the net effect of his new student loans proposal, and the spending-side effect of his “making work pay” credit and his expansion of the earned income and child credits.

You can also see that he would increase spending for non-defense discretionary. The red bar on defense, in contrast, is the amount that he would shrink defense spending. You can see he would make a similar change in the Medicare spending increase.

What about the yellow bars? They dominate the graph. They show the spending that will occur if we follow the baseline. For the top two bars, that’s a concept that we just do what we did last year, and increase everything by inflation. For everything else, that’s the effect of the autopilot effect of mandatory spending programs.

Look at those bottom three bars. While we’re fighting about the new health entitlement (I’m opposed), federal Medicaid spending will grow $171 B without any Congressional Debate. Federal Medicare spending will grow (net of premiums) $367 B with almost no debate. And Social Security spending will be $408 B higher in 2019 than in 2009, if Congress keeps burying their heads in the sand for the next decade.

By all means, let’s debate and even fight about the green and red bars. But if we ignore the spending increases in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid that occur without any changes to law, it will all be for naught.

p.s. This trend gets worse in the second decade.