Dr. Goolsbee gets it wrong on the auto loans

This morning on Fox News Sunday, host Chris Wallace moderated a discussion about the auto industry. One of his guests was Dr. Austan Goolsbee, who is a Member of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers and chief economist on the President’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board.

I want to focus on some incorrect and inflammatory statements by Dr. Goolsbee this morning:

Chris Wallace: I also want you to talk about the clash between policy and profits. The governments wants General Motors to make small cars, fuel-efficient cars, while all the indications are, that according to the market, the cars they make most profit on are SUVs and pickup trucks. So which takes preference? Profits for the taxpayer shareholders, or environmental policy?

Dr. Goolsbee: The President made totally clear in his remarks, and he specifically said we are not going to be in the business of telling General Motors or anybody else what kind of cars to make, where they should open their plants, or anything of the sort. The President made clear we want to get out of this as quickly as possible. We are only in this situation because somebody else kicked the can down the road, and that’s really an understatement. They shook up the can, they opened the can, and handed to us in our laps.Senator Shelby knows that to be true. When George Bush put money in to General Motors, almost explicitly with the purpose, how many dollars do they need to stay alive until January 20th, 2009? There was no commitment to restructuring, to making these viable enterprises of any kind. They made none of the serious sacrifices. And Republicans in the Senate attached a list of conditions, they opposed George Bush’s intervention, because they said the unions had not made the following sacrifices. In the Obama plan, it asked more and received more from the unions and from the other stakeholders than the people that objected to the bailout last November asked for. So we have finally put them on that path.

This is incorrect. I will bite my lip, refrain from commenting on the tone, and focus on the facts.

History

At 3:30 pm on Sunday, November 30, 2008, a quiet meeting occurred at the Treasury Department in Secretary Hank Paulson’s office. Present for the Bush Administration were Treasury Secretary Paulson and Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez, White House Chief of Staff Josh Bolten, Deputy COS Joel Kaplan, White House Legislative Affairs chief Dan Meyer, Treasury Legislative Affairs head Kevin Fromer, and me. Present for the incoming Obama Administration were Deputy COS-designate Mona Sutphen, NEC-designate Dr. Larry Summers, Dan Turullo (now a Fed Governor), and WH Legislative Affairs-designate Phil Schiliro. We had requested the meeting. They agreed and asked that it be held outside the White House. It appeared to us that they were quite concerned about leaks, and about the risk of creating a public impression that they were working closely with us.

At that meeting, we (the Bush team) floated a proposal to establish an auto czar. President Bush would create a new position called a Financial Viability Advisor (FVA) through an executive order. The President would instruct the FVA, for any auto manufacturer that sought a “bridge loan,” to evaluate that firm’s restructuring plan for viability. If after 60 days (which the FVA could unilaterally extend for another 30) the firm did not have a plan to achieve viability, then the FVA would produce his own plan to make that firm viable. The draft executive order was explicit that the FVA could include a Chapter 11 bankruptcy in his plan. We invited the Obama team to suggest names for the Financial Viability Advisor, so that it would be someone with whom the new President would be comfortable.

Under the Bush team’s proposal to the Obama team, the current Secretary of the Treasury (Paulson) would provide bridge funding from the TARP, and he would state that, as a matter of policy, no further TARP funding would be made available except in support of (1) a plan certified as viable by the FVA, or (2) the FVA’s own plan.

The key to success of this plan was that the Obama team would publicly link arms with us and agree that they would continue the Paulson policy statement when they took over after January 20th. Thus, the auto company’s stakeholders would know that they had no wiggle room, and that they had no chance of getting additional funding from the next Administration. The Obama team would voluntarily commit itself to be bound by the restriction self-imposed by the Bush team.

Remember that this was one of two huge issues going on at the time. The bigger issue was the financial crisis, and we were nearing the limit on the $350 B of available TARP funds. We were concerned that another too-big-to-fail institution might fail before January 20th without Treasury having the funds available to prevent a systemic collapse. So our proposal to the Obama team was a package deal: we will announce the above process for autos, and we will ask Congress for the second $350 B of TARP funding, if the President-elect publicly supports us on both. They would join with us in convincing Congress to approve the last tranche of TARP funding, since we would need help with Congressional Democrats.

We saw two huge economic issues that posed grave risks to the economy and to a smooth transition. We proposed to work together with the incoming Administration in a way that we thought minimized these risks and would have positioned the new President as well as possible on January 20th. GM and Chrysler would not be in liquidation, and there would be a strict, tight, and enforceable deadline (of about March 1) and process for GM and Chrysler to become viable or to have time to prepare for an orderly Chapter 11 process. We would have a cushion in case another major financial institution failed in the last eight weeks, and the next President would not have to be bothered with having to ask Congress for the last $350 B from the TARP.

The Obama team were polite and professional. They listened carefully and gave little reaction in the meeting. We concluded based on their questions in that meeting that they were leaning against the proposal, because they did not want to be bound by the judgment of a Financial Viability Advisor – they wanted the ability to make decisions in the White House. They also appeared to want to avoid being bound by our strict definition of viability. (We defined a viable firm as one that would, under reasonable assumptions, have a positive net present value without additional taxpayer assistance.)

Dr. Goolsbee was not in this meeting. I do not know if he was aware of it, either back in November or this morning.

Despite multiple efforts to get the Obama team on board, they did not take up our proposal, nor did they suggest any modifications. At the end of that week we gave up on that approach and began to negotiate a bill with Speaker Pelosi, Chairman Barney Frank, and Chairman Chris Dodd that would provide bridge loans from previously appropriated non-TARP funds.Senate Republicans blocked that bill. Congress adjourned for the year and went home. In the last week of December, GM and Chrysler told us they would file under Chapter 11 in early January if they did not get loans from the TARP. They also told us, as did countless outside experts, that they were not ready for such a filing, and that Chapter 11 would lead to near-immediate liquidation. We estimated that about 1.1 million jobs would be lost if this happened.

Confronted with a choice between loaning TARP funds to GM and Chrysler, and allowing both to liquidate in the weeks before his successor took office, President Bush authorized loans from the TARP to GM and Chrysler. We had warned Senate Republicans earlier that month that the President would face this choice if legislation failed. This was (and still is) a politically unpopular decision, and was the least worst of two bad options. Based both on his public comments and what I saw privately, President Bush wanted to give the firms a limited amount of time and a hard back end to prepare for and, if necessary, to force an orderly Chapter 11 process. He also knew that President-elect Obama would be facing tremendous challenges in his first days in office.Despite their different political parties and policy perspectives, President Bush stressed that we needed to provide his successor with the time and space he would need in the opening weeks of his Presidency.

Structure of the December loans to GM and Chrysler

In the last few days of December, Treasury loaned $24.9 B from TARP to GM, Chrysler, and their financing companies.

According to the terms of the loan (see pages 5-6 of the GM term sheet), by February 17th GM and Chrysler would have to submit restructuring plans to the President’s designee (and they did).

Each plan had to “achieve and sustain the long-term viability, international competitiveness and energy efficiency of the Company and its subsidiaries.” Each plan also had to “include specific actions intended” to achieve five goals. These goals came from the legislation we negotiated with Frank, Pelosi, and Dodd:

- repay the loan and any other government financing;

- comply with fuel efficiency and emissions requirements and commence domestic manufacturing of advanced technology vehicles;

- achieve a positive net present value, using reasonable assumptions and taking into account all existing and projected future costs, including repayment of the Loan Amount and any other financing extended by the Government;

- rationalize costs, capitalization, and capacity with respect to the manufacturing workforce, suppliers and dealerships; and

- have a product mix and cost structure that is competitive in the U.S.

The Bush-era loans also set non-binding targets for the companies. There was no penalty if the companies developing plans missed these targets, but if they did, they had to explain why they thought they could still be viable. We took the targets from Senator Corker’s floor amendment earlier in the month:

- reduce your outstanding unsecured public debt by at least 2/3 through conversion into equity;

- reduce total compensation paid to U.S. workers so that by 12/31/09 the average per hour per person amount is competitive with workers in the transplant factories;

- eliminate the jobs bank;

- develop work rules that are competitive with the transplants by 12/31/09; and

- convert at least half of GM’s obliged payments to the VEBA to equity.

If, by March 31, the firm did not have a viability plan approved by the President’s designee, then the loan would be automatically called. Presumably the firm would then run out of cash within a few weeks and would enter a Chapter 11 process. We gave the President’s designee the authority to extend this process for 30 days.

In another error this morning, Dr. Goolsbee claimed the “Obama plan, it asked more and received more from the unions and from the other stakeholders than the people that objected to the bailout last November asked for.” As I wrote last Monday (Understanding the GM bankruptcy), I have seen no convincing evidence that GM workers will now be paid competitive compensation with transplant workers, nor that the work rules are competitive with the transplants. The negotiations led by the Obama team did meet the Corker targets for the unsecured debt holders and the retiree benefits, but current workers still look to have received a relatively good deal.

Chronology

November 30: Bush team proposes joint solution to Obama team.

The following week: Obama team declines to respond. Bush team begins negotiations with House and Senate Democrats.

Mid-December: Bush team negotiates compromise legislation with House and Senate Democrats. Senate Republicans block the legislation. Congress goes home.

Late December: President Bush authorizes the above-described three month loans to GM and Chrysler.

January 20: President Obama takes office.

Mid-February: GM and Chrysler submit their first viability plans, per the terms of the Bush-era loans.

End of March: President Obama says GM and Chrysler have failed to develop viable plans, as required by the Bush-era loans. He gives Chrysler 30 more days, and GM about 60 until the end of May.

End of April: Chrysler files Chapter 11 with a pre-packaged plan negotiated largely by the Obama Administration.

June 1: GM does the same. Chrysler emerges from Chapter 11.

Responding to Dr. Goolsbee

Let’s again examine Dr. Goolsbee’s claim:

We are only in this situation because somebody else kicked the can down the road, and that’s really an understatement. They shook up the can, they opened the can, and handed to us in our laps. Senator Shelby knows that to be true. When George Bush put money in to General Motors, almost explicitly with the purpose, how many dollars do they need to stay alive until January 20th, 2009? There was no commitment to restructuring, to making these viable enterprises of any kind. They made none of the serious sacrifices.

Even if Dr. Goolsbee was not privy to the quiet discussion we had with the senior Obama team last November, the public record refutes his claim:

- The Obama team declined to respond to the Bush team’s offer to work together to create a joint process that would have resulted in a resolution by March 1st or April 1st, rather than by June 1st for Chrysler and maybe September 1st for GM.

- We then worked with the Democratic majority to enact legislation that would have limited funds to be available only to firms that would become viable.

- After Congress left town for the holidays without having addressed the issue, President Bush was faced with a choice between providing loans and allowing these firms to liquidate in early January, which would have further exacerbated the economic situation for the incoming President. President Bush chose to provide the loans.

- We provided GM and Chrysler with sufficient funds to get to March 31st, not January 20th, and in those loans we gave the incoming Administration the ability to extend them for 30 more days.

- The loans were conditioned on restructuring to become viable, with a precise definition of viability, specific restructuring goals, and quantitative targets.

- The Obama Administration followed the restructuring process laid out in the Bush-era loans. They are now measuring that deal against the targets established in the Bush-era loans. The only changes the Obama team made were that they extended GM for 60 days rather than 30, and the Obama Administration directly inserted themselves into the negotiations as the pre-packager.

Dr. Goolsbee’s comments this morning were both inflammatory and incorrect.

Working in the West Wing: Doing a TV news interview on the North Lawn

This is the second in a series of occasional posts about the nitty gritty of working in the West Wing of the White House. I am describing things as they were in the Bush Administration. YMMV in the Obama Administration. Again, it seems a bit silly to write about such trivial details, but given the positive feedback on the first post in this series, here goes.

I did my first TV interview at the beginning of 2008 shortly after being promoted. At first it was stressful, and it took me a while to get used to it. Now that I’m on the outside, I do an occasional interview on CNBC, Fox, or CNN. Today I’d like to describe the mechanics of doing a TV news interview from the North Lawn of the White House. Even though I had worked in the White House for more than five years before my first on-camera interview, I did not know any of this until I actually had to do it.

Today is Jobs Day: the first Friday of the month, when the Labor Department releases the monthly employment report. The employment report is generally the most important economic data point of the month, and the business news channels (CNBC, Bloomberg, and Fox Business) always cover it. They always ask for someone from the Administration to comment on the data and what it means for the economy and the policy agenda. I see the Vice President’s economic advisor, Jared Bernstein, is doing CNBC now. In 2008, CEA Chairman Dr. Ed Lazear and I typically did this duty.

The jobs report is released at 8:30 AM on Friday. As with all economic data releases, Administration officials are embargoed from talking about it publicly for one hour after the release. This gives the markets time to process the data without the Administration’s viewpoint.

For each show broadcasting at 9:30 AM, a network producer negotiates with a staffer in the White House press shop. For us it was Eryn Witcher, a top-notch professional with prior experience in TV news who now works as the communications director at Stanford’s Hoover Institute. Eryn would negotiate with the producers and set Ed and/or me up with interviews.

Ed and I would talk the night before about the upcoming data and what we might say about it on the air. We were among a handful of officials who got the data reports before they were released, so that we could advise the President. Ed and his staff also used that data to prepare the daily “economic data memos” that the President received each morning.

We would generally watch the CNBC commentary immediately after the data release (at 8:30 AM sharp) to see if we had missed anything, and to take a temperature check on the initial market reaction and expert analysis. We would generally be prepped by Ed’s chief of staff, Pierce Scranton, who had an uncanny ability to predict what questions we would be asked, and coached us on how to give a short effective answer. If he wasn’t fighting other fires, Deputy Press Secretary Tony Fratto would also sit in the prep session.

A little after 9 AM someone would do my makeup in my office. Around 9:15 Eryn and I (or Eryn and Ed) would walk out to the North Lawn. You need a good TV tie (no busy patterns), straight collar (I was often scolded for button down collars), and American flag pin. After a while I got my own earpiece that I would bring out with me, so I wouldn’t have to use the common one that everyone else uses. It’s also nice to know you won’t lose the earpiece during the interview.

Each network has a TV camera set up in an area on the North Lawn next to the driveway from Pennsylvania Avenue to the West Wing entrance. The networks semi-permanently set up shop there in 1998 during the Monica Lewinsky scandal, and the gravel-filled area became known as Pebble Beach. It was refurbished during the Bush Administration with slate and the cameras and tripods are covered with heavy green canvas when they’re not being used. It is now referred to as Stonehenge, to which it bears a vague resemblance.

The cameras are in a long line next to each other. Each is set up so that the person on air has the north entrance to the White House residence in the background. Because of the different camera positions, each has a slightly different angle on the White House. On the night of a big Presidential speech from the White House, try quickly switching channels and you can see the different angles.

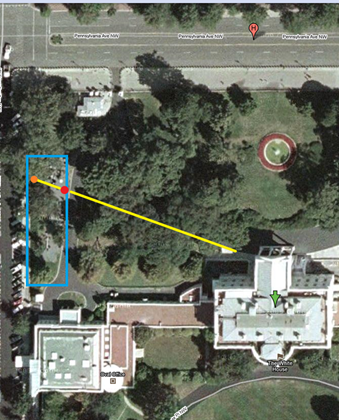

Here’s a diagram for CNBC (roughly). As always, you can click on the picture for a larger view.

The West Wing is the square building in the lower-left (southwest) corner. The residence is in the lower-right corner, and that’s Pennsylvania Avenue up top.

The blue box surrounds Stonehenge with all the TV cameras. When you’re on CNBC you stand at the red dot, facing the camera at the orange dot. The yellow line shows the camera angle, extended to capture the north entrance to the Residence in the background.

If you look closely, to the right (east) of the blue box you can see the driveway that heads south from the Northwest Appointment Gate to the West Wing entrance. Visitors with appointments in the West Wing walk up this driveway, and you can occasionally see them passing behind someone being interviewed on TV (especially on the evening news broadcasts). If they’re walking from left to right on your screen, they’re arriving at the West Wing. Right to left, they’re leaving.

About 9:15 AM Eryn and I would walk out to Stonehenge. We would greet the cameraman and a producer, and I’d get miked up. All the producers I met were friendly and professional, and the cameraman are universally great. I would stand at the red dot facing the camera. My earpiece cord would clip to the back of my jacket collar. The cameraman would connect an audio cable to that cord, and there’s a small box at about waist high with a volume dial. He attaches a tiny microphone to my lapel and I’m all set.

The cameraman then adjusts the camera for the shot. I’m generally looking at myself on a monitor below the camera: tie is straight, flag pin is upright. (Left and right are reversed from what you’re used to in a mirror. That takes getting used to.)Around 9:25, I’ll hear audio of the show in my earpiece, and then a voice:

Voice 1: Mr. Hennessey, this is

[Bob] at CNBC headquarters. Can you hear me?Me: Yes I can, Bob.

Voice 1: And you can hear the program?

Me: Yes.

Voice 1: Great. Can you count to ten for me, please, so we can do an audio check?

Me: 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,…

Voice 1: That’s perfect. Thank you.

After another minute, another voice, the producer for my segment of the show.

Voice 2: Mr. Hennessey, this is [Tom]. We’re going to a commercial break, and will be going to you in about 2 minutes. You’ll be interviewed by [Erin / Mark / Erin & Mark].

Me: Sounds great. Thank you.

During my first few interviews, the substance wasn’t that difficult for me. I had been prepping principals for interviews and writing talking points for more than 13 years, now I just had to do the talking. The hard parts were the nerves and the physical mechanics:

- Look at the camera lens. Don’t let your eyes wander.

- Smile.

- Try not to “um” and “you know” too much.

- Slow down.

- Relax.

Also, TV moves very quickly. Long answers don’t work, so I had to train myself to make my point in one or two sentences, rather than four or five. (That’s difficult for me.) If you go on too long, you’ll start hearing the anchor trying to jump in and move things along. And before you know it, you’re done.

After the interview, you unmike, thank the cameraman and producer, and you’re done. If you have another interview, you move down the line and repeat. If not, head inside, take off the makeup, and get feedback from your colleagues and friends who email that they saw you on TV.

I only did a few in-studio interviews, and guest hosted CNBC’s Squawk Box once. I was blown away by the ability of the anchors to multitask, and how quickly they think and react. While one of them is talking on camera, another is checking market news or data on their screen, or scanning email. Their producers are talking to them in their earpieces, and they are talking on camera with each other and the guests. The coordination, reaction times, ability to adapt and improvise, and teamwork among the anchors and their producers are amazing. Beginning that day, and ever since I have developed tremendous respect for those business news anchors hosting live fast-moving discussions. I have enough trouble doing a single five minute segment, and they do it for 2-3 hours five days a week.

Today’s jobs report

On the first Friday of each month the Labor Department releases the employment report for the prior month. In the White House we used to call it Jobs Day, and it’s a fairly big deal when the economy is in transition.

Today is Jobs Day. Here are the two most important facts from the May employment report:

- The U.S. economy lost a net 345,000 jobs in May. This bad news beat expectations, so markets reacted positively.

- The unemployment rate jumped from 8.9% to 9.4%, the highest since August 1983.

In an effort to build traffic, I am going to start posting occasionally on other blogs and websites. So you can read today’s post on the Jobs Day report on National Review Online’s The Corner. I hope you don’t mind the extra click.

Will the stimulus come too late?

I began this blog at the end of March after the stimulus bill had become law. I had been struck by how much the stimulus debate had focused on whether the bill was efficient. (It clearly was not.) There was much less discussion of whether the stimulus would be effective, and of the timing of the macroeconomic boost.

Everyone wants to know when the U.S. economy will start growing. I will focus on a related question: when will the stimulus law begin to have a significant positive effect on U.S. economic growth? And could it have come sooner if the Administration had done something different?

I believe the Administration made an enormous mistake in its legislative implementation of the stimulus. As a result, the boost to GDP will come six to nine months later than it needed to (maybe more). Given the President’s desire to do a large fiscal stimulus, and given his policy preferences, he could have had a different bill that would have been producing significant GDP growth beginning now, rather than in the middle of next year. That’s a huge mistake with real consequences for the U.S. and global economies.

To illustrate this point, let me classify four types of fiscal stimulus:

- a permanent tax cut;

- a temporary tax cut;

- one-time checks to people independent of their tax liabilities; and

- increased government spending through federal and state bureaucracies: infrastructure, energy spending, etc.

There is of course a fifth option: no fiscal stimulus law.

If you’re going to do a fiscal stimulus (big if), the best kind is a permanent tax cut. It is effective, efficient, and fast:

- effective – People spend a large proportion of a permanent tax cut. This is derived from Milton Friedman’s “permanent income hypothesis.”

- efficient – People spend their own money on themselves, so they waste very little of it, and they spend it on things that matter to them. Again, see Milton Friedman.

- fast – Checks are delivered quickly, and people spend most of their own money soon after they get the check.

This was part of the short-term logic behind the 2003 tax cut, which we designed to foster both short-term and long-term economic growth. I also have a strong general policy preference for lower taxes rather than more government spending, but that’s a separable question from how it works as short-term stimulus.

In 2008 we knew we could not get a Democratic Congress to enact a permanent tax cut. Q: Do you then go for a temporary tax cut, or do nothing? The President thought the risks of an economic slowdown in 2008 were significant enough that it made sense to pursue a (second best) temporary tax cut with the Congress.

Like the 2003 law, the 2008 law got the bulk of its short-term GDP boost by advancing tax refunds from the year to come, and delivering them as checks from the IRS to taxpayers. As in 2003, the checks were delivered to taxpayers in the summer (mid-June to early-August), and consumers immediately started spending a portion of their rebates.

Because the 2008 law was a temporary tax cut, taxpayers spent a smaller proportion of it than anyone would have liked. While designing the law, we assumed about 1/3 would be spent, and much of that fairly quickly. The rest would be saved, which is also good but doesn’t help short-term GDP growth. Economists agree that GDP in Q3 and Q4 of 2008 was higher than it otherwise would have been because of the 2008 stimulus law. It was efficient, fast, yet only partially effective, with a smaller GDP boost than we would have liked:

- efficient – People were again spending their own money on themselves. You get very little waste, and people know what they want and need.

- fast – Checks were delivered quickly, and much of the spending that did occur happened in Q3, with some in Q4, and with very little left by Q1 of 2009.

- only partially effective – Because it was a temporary tax cut, people saved a lot of their checks, as we expected. Still we got a GDP bump in Q3 and Q4, and in retrospect we certainly needed it.

The 2008 law was mostly (2) from my list above – a temporary tax cut. Some of the money went to (3), checks to people who didn’t pay income taxes. This was necessary to reach a compromise with a Democratic Congressional leadership that placed a high priority on the distributional effects of the law. Speaker Pelosi insisted that poor people who owed no income taxes still get “rebate” checks, and that high-income taxpayers get nothing. So the 2008 stimulus law was mostly (2) with a little bit of (3).

Now fast forward to January of 2009, when President Obama proposed an enormous fiscal stimulus. The President’s mistake was in largely deferring to Congress on the composition of the stimulus bill. Rather than allowing Congress to pump hundreds of billions of dollars through slow-spending and inefficient bureaucracies, the President should have insisted that Congress instead send all the funds directly to the American people and let them spend it quickly and efficiently. Given his policy preferences, he could have directed a large share of those funds to poor people who don’t pay income taxes. He could have again mislabeled these payments as “tax cuts,” or just correctly labeled them as one-time entitlement payments. I would not have liked that policy, but it would have generated a faster macroeconomic boost than what he allowed Congress to do instead.

Let’s compare the two scenarios. The enacted 2009 stimulus is:

- effective (eventually) – Most of the spending through government bureaucracies will (eventually) increase GDP. Some of the funds transferred to State governments will be used to offset State spending or tax cuts that otherwise would have occurred, so there’s a loss. But clearly the proportion of the $787 B that will eventually increase GDP will be high, and much higher than if all the funds were given to individuals and families.

- inefficient – It will be inefficient in two senses. The spending represents the policy preferences of legislators (and all their ugly legislative deals and compromises), rather than the choices of hundreds of millions of Americans who presumably know better how they would like money spent on them. The spending will also be wasteful, and we are starting to see signs of this in the press.

- s-l-o-o-o-w – CBO says that $25 B of spending had gone into the economy by May 22nd. That’s less than 4% of the total budgetary impact of that bill. Other news reports suggest that about $40 B is in the economy if you include the revenue side. Remember that almost all of the 2008 stimulus was in private hands by August 1. We will get very little GDP boost from fiscal stimulus in Q3 of 2009, and not much in Q4 either. The stimulus will begin to ramp up in Q1 of next year, and be in full swing by Q2 and Q3 of 2010.

Had the President instead insisted that a $787 B stimulus go directly into people’s hands, where “people” includes those who pay income taxes and those who don’t, we would now be seeing a stimulus that would be:

- partially effective but still quite large – Because it would be a temporary change in people’s incomes, only a fraction of the $787 B would be spent. But even 1/4 or 1/3 of $787 B is still a lot of money to dump out the door. The relative ineffectiveness of a temporary income change would be offset by the enormous amount of cash flowing.

- efficient – People would be spending money on themselves. Some of them would be spending other people’s money on themselves, but at least they would be spending on their own needs, rather than on multi-year water projects in the districts of powerful Members of Congress. You would have much less waste.

- fast – The GDP boost would be concentrated in Q3 and Q4 of 2009, tapering off heavily in Q1 of 2010.

Why did the President not do this? Discussions with the Congress began in January before he took office, and he faced a strong Speaker who took control and gave a huge chuck of funding to House Appropriations Chairman Obey (D-WI). I can think of three plausible explanations:

- The President and his team did not realize the analytical point that infrastructure spending has too slow of a GDP effect.

- They were disorganized.

- They did not want a confrontation with their new Congressional allies in their first few days.

I think the Administration now recognizes this problem. Last month when they released a CEA paper “Estimates of Job Creation from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009,” the paper danced around the timing of job growth and government outlays in 2009 and 2010. Tips for reporters: (1) ask the Administration to give you OMB estimates of quarterly cash flows for the stimulus law, and (2) ask them to give you the quarterly GDP and job growth estimates behind this CEA paper. I know the first one exists, and I’d bet heavily the second does as well.

Fortunately, CBO Director Doug Elmendorf just gave a presentation titled “Implementation Lags of Fiscal Policy” to the IMF’s conference on fiscal policy. All of the following data are from his presentation.

The final 2009 stimulus law broke down like this:

|

10-yr total |

% of total |

|

|

Discretionary spending (highways, mass transit, energy efficiency, broadband, education, state aid) |

$308 B |

39% |

|

Entitlements (food stamps, unemployment, Medicaid, refundable tax credits) |

$267 B |

34% |

|

Tax cuts |

$212 B |

27% |

|

Total |

$787 B |

100% |

The problem is that only 11% of the first line (discretionary spending) will be spent by October 1 of this year. In contrast, 31-32% of the entitlement and tax cuts lines will be out the door by that time. (I have questions about the speed of the entitlement part. The bulk of that is Medicaid spending, and it’s not clear to me that a Federal payment to a State means the cash is immediately flowing into the private economy.)

If we extend our window to October 1, 2010, then less than half the discretionary spending will be out the door, while almost 3/4 of the entitlement spending and all of the tax cuts will be out the door and affecting the economy. The largest part of the stimulus law is therefore also the slowest spending part. This is fine if you’re trying to increase GDP growth over the next 2-4 years. If you’re going for short-term GDP growth, it makes no sense.

Director Elmendorf drills down further into discretionary spending and shows that defense spending happens quickly, highways and water extremely slowly:

- If you allocate $1 to defense spending, 65 cents has been spent within one year.

- If you allocate $1 to highway spending, 27 cents has been spent within one year.

- If you allocate $1 to water projects, only 4 cents has been spent within one year.

In fact, the infrastructure spending in the stimulus law will peak in fiscal year 2011, which goes from October 1, 2010 to September 30, 2011. That’s too late from a macro perspective.

The Director further points out that the 2009 stimulus law created many new programs. This slows spend-out, as it takes time to create and ramp up the new programs.

The Administration has made much of working with federal and state bureaucracies to find “shovel-ready” projects to accelerate infrastructure spending. All of my conversations with budget analysts suggest this claim is tremendously overblown, and Director Elmendorf asks, “Is this practical on a large scale?”

The 2009 stimulus law will increase U.S. economic growth. But the actuals are matching the budget analysts’ projections for the speed at which that effect will occur.

I would not have liked a stimulus law that would have given cash to people who didn’t pay income taxes. But from a macroeconomic perspective, we need the faster economic growth now. Had the President and his team insisted on giving money to people (taxpayers or not) rather than to bureaucracies, we would be seeing a huge growth spurt in Q3 and Q4 of this year.

It is sad that instead we have to wait until the middle of next year because the White House deferred to Congressional desires to spend on infrastructure. This strategic mistake was avoidable, and the recovery will be delayed because of it.

Parsing the President’s health care reform letter

The White House has released a letter from the President to the two Senate Chairmen who are working on (different) versions of health care reform: Senator Kennedy (D-MA), Chairman of the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, and Senator Max Baucus (D-MT), Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. The letter is dated yesterday and was delivered as part of a White House meeting between the President and Senate Democratic leaders, including the two Chairmen.

This important letter attempts to shape the pending legislation. It makes new proposals, and it tries to set boundaries to constrain the work of the Chairmen. I am going to walk through the letter and explain what I think it means. I will walk through it in sequence, but will cut out the fluff, and occasionally add emphasis in bold. Each of these quotes could merit a post by itself. I will instead provide a survey of the whole letter. The first notable text is the second paragraph:

Soaring health care costs make our current course unsustainable. It is unsustainable for our families, whose spiraling premiums and out-of-pocket expenses are pushing them into bankruptcy and forcing them to go without the checkups and prescriptions they need. It is unsustainable for businesses, forcing more and more of them to choose between keeping their doors open or covering their workers. And the ever-increasing cost of Medicare and Medicaid are among the main drivers of enormous budget deficits that are threatening our economic future.

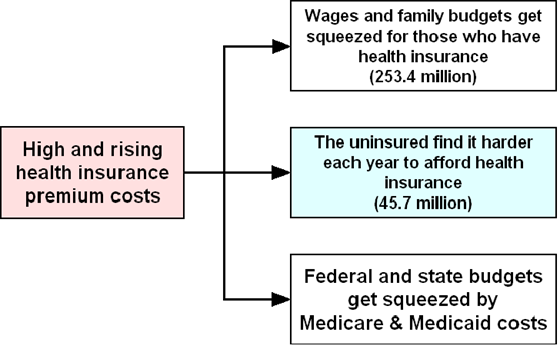

This is fantastic, especially as 2. He is focusing on health cost growth as the underlying problem, rather than just focusing on the uninsured, which is only one symptom of the problem. I wrote about this in mid-April: By focusing only on covering the uninsured, are we solving the wrong problem? Here’s the key picture from that post. We need to focus on the red box, and not just the blue box.

The President’s letter continues:

We simply cannot afford to postpone health care reform any longer. This recognition has led an unprecedented coalition to emerge on behalf of reform — hospitals, physicians, and health insurers, labor and business, Democrats and Republicans. These groups, adversaries in past efforts, are now standing as partners on the same side of this debate.

There is a less noble explanation for the existence of this coalition. I wrote in mid-May, “

At this historic juncture, we share the goal of quality, affordable health care for all Americans. But I want to stress that reform cannot mean focusing on expanded coverage alone. Indeed, without a serious, sustained effort to reduce the growth rate of health care costs, affordable health care coverage will remain out of reach. So we must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care.

This is an astonishing paragraph from a Democratic President. As he has done in the past, he says his goal is health care for all Americans, rather than health insurance for all Americans. This language will allow him to declare victory with a bill that does not provide universal pre-paid health insurance.

He then reiterates that expanded coverage is insufficient. A bill “must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care.” This is fantastic and unexpected from a Democrat.

The President’s letter then veers wildly off course. That paragraph continues:

… So we must attack the root causes of the inflation in health care. That means promoting the best practices, not simply the most expensive. We should ask why places like the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, and other institutions can offer the highest quality care at costs well below the national norm. We need to learn from their successes and replicate those best practices across our country. That’s how we can achieve reform that preserves and strengthens what’s best about our health care system, while fixing what is broken.

Geographic disparities in health spending are enormous, and if we could somehow magically reduce spending in high-cost areas to match that in low cost areas, without sacrificing too much quality, then we would make major progress in reducing the level of national health spending. Budget Director Peter Orszag is the primary proponent of this argument, since before he entered the Administration.

But the Administration has no plan and no proposals that would actually reduce geographic disparities in health care. They have proposals which would provide people with more information about the health care they use, but they have not proposed to change the incentives people have to use that care. If you don’t change the incentives, you will make no significant progress in reducing geographic spending disparities or slowing health cost growth. I wrote about this in late April: Slowing health cost growth requires information AND incentives, and then found that CBO had already made this point.

More importantly, it is absurd to say that geographic disparities are “the root causes of the inflation in health care.” We know what drives health cost growth: (1) technology, (2) income growth, (3) increases in third party payment, and (4) aging of the population. Some argue that administrative costs also contribute to growth, but I’m skeptical. We also know that the first three reasons account for two-thirds to nearly all of cost growth, depending on which study you prefer.

The President’s letter correctly identifies the problem to be solved as health cost growth, and then completely misdiagnoses the sources of that growth. The Administration continues to grossly foul up the problem definition, not propose a solution, and get a free ride from a lazy and compliant press corps. You cannot slow health spending growth merely by stating a vague intent to do so.

The letter continues:

The plans you are discussing embody my core belief that Americans should have better choices for health insurance, building on the principle that if they like the coverage they have now, they can keep it, while seeing their costs lowered as our reforms take hold.

Two things jump out from this sentence. The first is a clear and oft-repeated signal that “if [you] like the coverage [you] have now, [you] can keep it.” The President says this is a core belief. It also protects the Administration from one of the most effective attacks on expansions of government health care: that it will squeeze our your private care. This is tactically smart.

The second is the return to “seeing their costs lowered as our reforms take hold.” This addresses the first box on the right side in my diagram above, and I compliment the President and his team for identifying that growing health spending hurts the more than 100 million Americans who now have health insurance, and not just those who lack it.

But for those who don’t have such options, I agree that we should create a health insurance exchange … a market where Americans can one-stop shop for a health care plan, compare benefits and prices, and choose the plan that’s best for them, in the same way that Members of Congress and their families can.

- A (singular) exchange, or 50 State exchanges? There’s a big difference.

- I have never been enamored of the “one-stop shopping” argument. I’m not opposed to it, it just doesn’t excite me. Mostly I fear that exchanges become vehicles for Washington-directed redistribution.

- It is fascinating that he takes the traditional liberal argument that “you deserve health care that is good as Members of Congress get,” and turns it into “Americans can … choose the plan that’s best for them, in the same way that Members of Congress and their families can.” This is creative.

None of these plans should deny coverage on the basis of a preexisting condition, …

The hardest problem in health care reform is how to deal with the small percentage of Americans with predictably high health costs. To quote Harvard’s Dr. Kate Baicker:

Uninsured Americans who are sick pose a very different set of problems. They need health care more than health insurance. Insurance is about reducing uncertainty in spending. It is impossible to “insure” against an adverse event that has already happened, for there is no longer any uncertainty. If you were to try to purchase auto insurance that covered replacement of a car that had already been totaled in an accident, the premium would equal the cost of a new car. You would not be buying car insurance – you would be buying a car. Similarly, uninsured people with known high health costs do not need health insurance – they need health care. Private health insurers can no more charge uninsured sick people a premium lower than their expected costs. The policy problem posed by this group is how to ensure that low income uninsured sick people have the resources they need to obtain what society deems an acceptable level of care and ideally, as discussed below, to minimize the number of people in this situation.

We need to distinguish between the uninsured and the uninsurable. The uninsured lack health insurance for a wide variety of reasons. Some uninsured are healthy, some are sick.

The uninsurable are those who are already sick or injured, and who have predictably high future health costs. If you have an incurable disease, you are uninsurable, because there is little uncertainty about your future spending. (I’m oversimplifying -there is little uncertainty that you will have high health costs.) As Kate points out, “Uninsured people with known high health costs do not need health insurance – they need health care.” The policy problem posed by this group is how to ensure that low income uninsured sick people have the resources they need to obtain what society deems an acceptable level of care.

So when the President says that “None of these plans should deny coverage on the basis of a preexisting condition,” the practical effect is that health insurance plans will be required to provide health care to the uninsurable, label it as “insurance,” and then charge healthy people higher premiums than are merited by their own health status. It’s a way of hiding the cross-subsidization.

… and all of these plans should include an affordable basic benefit package that includes prevention, and protection against catastrophic costs.

The word “basic” is unusual from a Democrat. The traditional Washington health debate has Republicans (generally) arguing that we should want more people to be able to afford access to “basic” health insurance, while Democrats (especially those farther Left) saying everyone has a right to “good” health insurance. Setting aside the access vs. right debate for the moment, the word “basic” is a more centrist choice than I would have expected from this President.

He then runs into one of the classic problems of government-designed health care reform: who defines the benefit package? By saying that all of these plans should include X, he is punting the question of who gets to define X, and how specific will they be?Governments have a terrible track record of political micromanagement of medical benefits.

I strongly believe that Americans should have the choice of a public health insurance option operating alongside private plans.

Note that he chose “I strongly believe that Americans should have” rather than the stronger “Americans must have.” Despite the urgings of the Left, the President is leaving himself room to jettison the “public option” if that is the price of getting the Republican votes he may need. Also, he says “alongside private plans,” again emphasizing that the public option will not, in his view, squeeze out private coverage. I think he’s wrong and it will squeeze out private coverage, and would point to what his Administration is trying to do to Medicare private plans as proof.

I understand the Committees are moving towards a principle of shared responsibility — making every American responsible for having health insurance coverage, and asking that employers share in the cost. I share the goal of ending lapses and gaps in coverage that make us less healthy and drive up everyone’s costs, and I am open to your ideas on shared responsibility. But I believe if we are going to make people responsible for owning health insurance, we must make health care affordable. If we do end up with a system where people are responsible for their own insurance, we need to provide a hardship waiver to exempt Americans who cannot afford it. In addition, while I believe that employers have a responsibility to support health insurance for their employees, small businesses face a number of special challenges in affording health benefits and should be exempted.

This is a fairly hard slap at a mandate (individual or employer). “I understand [you] are moving toward … I share the goal … and I am open to your ideas on shared responsibility” is not a ringing endorsement of a mandate. He then guts the universal nature by saying that it should exempt “Americans who cannot afford it” as well as small businesses. These exemptions would create tremendous distortions and inequities. The resulting patchwork mandate would be a mess. With this paragraph, I think the President weakens the prospect of a mandate becoming law.

Health care reform must not add to our deficits over the next 10 years — it must be at least deficit neutral and put America on a path to reducing its deficit over time. To fulfill this promise, I have set aside $635 billion in a health reserve fund as a down payment on reform. This reserve fund includes a numb

er of proposals to cut spending by $309 billion over 10 years –reducing overpayments to Medicare Advantage private insurers; strengthening Medicare and Medicaid payment accuracy by cutting waste, fraud and abuse; improving care for Medicare patients after hospitalizations; and encouraging physicians to form “accountable care organizations” to improve the quality of care for Medicare patients. The reserve fund also includes a proposal to limit the tax rate at which high-income taxpayers can take itemized deductions to 28 percent, which, together with other steps to close loopholes, would raise $326 billion over 10 years.

I am committed to working with the Congress to fully offset the cost of health care reform by reducing Medicare and Medicaid spending by another $200 to $300 billion over the next 10 years, and by enacting appropriate proposals to generate additional revenues. These savings will come not only by adopting new technologies and addressing the vastly different costs of care, but from going after the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, including unmanaged chronic diseases, duplicated tests, and unnecessary hospital readmissions.

- “It must be at least deficit neutral” – Good.

- “and [must] put America on a path to reducing its deficit over time” – Even better, if he were to actually propose a policy that might do this. Without such a proposal, this is empty and weak.

- “I have set aside $635 billion in a health reserve fund as a down payment on reform” – Horrible. He wants to create the entire new obligation, but fund only about half of it.

- “… cut spending by $309 billion over 10 years” – True, but his budget hides $330 B in additional spending on doctors and $17 B to expand Medicaid, so the net is a Medicare/Medicaid spending increase of $38 billion over 10 years. (See table S-5 on page 121 of the President’s budget.) The President’s budget increases spending on these entitlements, and uses a baseline game to claim budgetary savings to offset a new health entitlement.

- “… cutting waste, fraud and abuse” – This is the old chestnut to suggest that the cuts are good policy and won’t hurt. There is waste, fraud, and abuse, but the cuts will also involve real reductions in payments to health providers, and they will hurt (which doesn’t make them wrong to do).

- “… a proposal to limit the tax rate at which high-income taxpayers can take itemized deductions to 28 percent” – Democrats in Congress rejected this months ago.

- “… by reducing Medicare and Medicaid spending by another $200 to $300 billion over the next 10 years” – Excellent. Will he provide specifics? I would be happy to suggest some.

- “… and by enacting appropriate proposals to generate additional revenues.”- aka “raise more taxes” – Horrible from my perspective.

- “… going after the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, including unmanaged chronic diseases, duplicated tests, and unnecessary hospital readmissions.” – As I said earlier, these are not the key drivers of skyrocketing health care costs, and it is misleading and irresponsible to claim they are.

To identify and achieve additional savings, I am also open to your ideas about giving special consideration to the recommendations of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), a commission created by a Republican Congress. Under this approach, MedPAC’s recommendations on cost reductions would be adopted unless opposed by a joint resolution of the Congress. This is similar to a process that has been used effectively by a commission charged with closing military bases, and could be a valuable tool to help achieve health care reform in a fiscally responsible way.

This is new and interesting to me. “A commission created by a Republican Congress” is odd, since MedPac is not known as a nonpartisan advisory group. It is also odd to imagine giving MedPac real decision-making authority, given that it is comprised of representatives of provider groups (doctors, hospitals, nurses, etc.)

I know that you have reached out to Republican colleagues, as I have, and that you have worked hard to reach a bipartisan consensus about many of these issues. I remain hopeful that many Republicans will join us in enacting this historic legislation that will lower health care costs for families, businesses, and governments, and improve the lives of millions of Americans. So, I appreciate your efforts, and look forward to working with you so that the Congress can complete health care reform by October.

I can read this either way. My gut says this means, “Get me a bill by October.” I would prefer it be broadly bipartisan, but don’t let the lack of Republican support prevent you from getting me a bill.

Summary & Conclusions

The news in this letter is:

- The President continues his rhetorical focus on reducing long run health costs in addition to expanding coverage.

- While appearing to push for a public option and universality, he is leaving himself room to compromise on both if needed to get a bill to his desk.

- He has made a mandate harder to legislate by insisting on large exemptions, and he has not signaled any support for a mandate. Goodbye mandate, I think.

- He is insisting on deficit neutrality over 10 years and reducing the deficit in the long run, while not proposing policies that achieve either goal. He is opening the door to more Medicare and Medicaid savings to reach these goals and has floated a $200-$300 B number without specifics.

- He has opened the door to a binding commission to cut Medicare and Medicaid spending, modeled after the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process.

I have mixed conclusions:

- At the 30,000-foot level, he has broken new ground for Democrats in defining the problem correctly as unsustainable health cost growth, rather than the subsidiary problem of the uninsured. I compliment him for this.

- At the 5,000-foot level, he botches the problem definition by focusing on geographic disparities while ignoring the commonly acknowledged major drivers of health spending increases: technology, income growth, and third party payment. This is a fatal flaw.

- He continues to assert that we must slow cost growth, without proposing any policy changes that would do so in a measurable way. This is an abdication of leadership and irresponsible.

- To genuinely slow health cost growth, you need to change incentives. Doing so involves political pain. Congress will not want to do that pain, and will not do so if the President doesn’t propose specifics.

- In addition, the short-term budget numbers still don’t add up. He has problems with the “down payment” meaning they’re not paying for the full new obligation, ignoring the doctors and Medicaid spending hidden in the baseline, and Congress rejecting his biggest tax increase proposal.

- I am glad that he is leaning against, or at least undermining, the case for a mandate.

- The MedPAC idea is interesting. It probably won’t work, but I don’t want to dismiss it out of hand.

The President’s letter makes it harder, not easier, to get a bill. While I like some elements of the letter, it is inconsistent with the President’s actual proposals. You cannot magically slow health spending growth without proposing policy changes that affect incentives and behavior. If the President is not willing to bite the bullet and lead on slowing long-term health cost growth, he will instead get a bill which is just a straight entitlement expansion, partly offset by Medicare Advantage cuts and tax increases, and obscured by budget gimmicks. His advisors will then have to construct a bogus argument that they have addressed long-term spending growth.

That would be a terrible outcome.

Understanding the GM bankruptcy

Many of you are new to this blog since I wrote extensively about autos six weeks ago. As background, I coordinated the auto loan process for President Bush last fall as the Director of the White House National Economic Council (the position now held by Dr. Lawrence Summers). I wrote a series of posts on the auto loans beginning when the President made his late-March announcements, and continuing into the spring. For reference, here are those posts:

- Auto loans: a deadline looms

- Auto loans: options for the President

- Auto loans: the Bush approach

- Auto loans: Chrysler gets an ultimatum, GM gets a do-over

- Auto loans: the press forgot to ask about the cost to the taxpayer

- Should taxpayers subsidize Chrysler retiree pensions or health care?

- The Chrysler bankruptcy sale

- Mixed results on the Chrysler announcement

This morning I posted some basic facts on the General Motors announcement. Now it’s time for some analysis. Like my post Understanding the President’s CAFE announcement, this is a monster post. I hope you find it valuable despite its length.

I want to try to tease apart the various questions that get conflated in the public forum. My primary goal is to give you a structure for thinking about the issue. My secondary goal is to persuade you to agree with my views on each question. I will be satisfied if you give me credit for achieving only the primary goal.

Here is how I tease apart the questions:

- What are the arguments for further government intervention?

- Given these arguments, should the U.S. government intervene further by putting more taxpayer funding at risk to prevent GM from liquidating?

- Is the pre-packaged bankruptcy likely to succeed?

- Is it fair?

- Did the government structure the taxpayer financing correctly?

- Will the Administration run GM?

Let’s take them one-by-one.

1. What are the arguments for further government intervention?

Today the President explained why he chose to put another $30.1 B of taxpayer funds at risk to prevent GM from liquidating now. Speaking about his decision on March 30th, he said today:

But I also recognized the importance of a viable auto industry to the well-being of families and communities across our industrial Midwest and across the United States. In the midst of a deep recession and financial crisis, the collapse of these companies would have been devastating for countless Americans, and done enormous damage to our economy — beyond the auto industry. It was also clear that if GM and Chrysler remade and retooled themselves for the 21st century, it would be good for American workers, good for American manufacturing, and good for America’s economy.

This is more expansive than what President Bush argued last December:

In the midst of a financial crisis and a recession, allowing the U.S. auto industry to collapse is not a responsible course of action. The question is how we can best give it a chance to succeed. Some argue the wisest path is to allow the auto companies to reorganize through Chapter 11 provisions of our bankruptcy laws – and provide federal loans to keep them operating while they try to restructure under the supervision of a bankruptcy court. But given the current state of the auto industry and the economy, Chapter 11 is unlikely to work for American automakers at this time.

The distinction is important. President Bush’s arguments were time-dependent: (a) we should try to prevent our weak economy from taking another big hit right now, and (b) let’s buy GM and Chrysler time to get ready to restructure. He also argued (c) that it was unfair to dump a liquidating auto industry on his successor (even if his successor might do something different than he would). It was a “too big to fail now” argument.

Today President Obama made it clear that he made the decision to commit additional funds, if his conditions were met, at the end of March. He then added new reasons to those expressed by President Bush: that America needs “a viable auto industry,” and that it would be good for America if GM and Chrysler survived. While he emphasizes what he would not do, “I refused to let these companies become permanent wards of the state,” President Obama defines a national interest in having auto manufacturers headquartered in the U.S. He reinforced that with his closing line, which was surreal:

And when that happens, we can truly say that what is good for General Motors and all who work there is good for the United States of America.

This is a big expansion of the justification for government intervention in the market. Ford is not failing, and Chrysler is emerging from bankruptcy. President Obama is arguing that American taxpayers need to fund the survival of a third (the biggest) U.S.-based auto manufacturer, because it is important “to the well-being of families and communities across our industrial Midwest and across the United States” and because “it would be good for American workers, good for American manufacturing, and good for America’s economy.” This argument could be extended to almost any large U.S. firm, at almost any time.

My view: I am extremely uncomfortable with the President’s expanded argument for further government intervention. Had the President instead argued, “The economy is beginning to recover, and we cannot jeopardize that with another major shock,” I would have been less uncomfortable with today’s commitment of additional taxpayer funds.

2. Given these arguments, should the U.S. government intervene further by putting more taxpayer funding at risk to prevent GM from liquidating?

The public debate has evolved in the past two months. Earlier this year the question posed was, “Should the Administration bail out GM?” The basic options were “yes,” “no,” and “only if they enter bankruptcy, and if they do they should try to pre-package it.” The President chose the last of these options. The President decided to put $30.1 B of additional taxpayer funding at risk to help prevent GM from liquidating in the near future, and to help them through a restructuring process.

The benefits and costs are similar to what I described in late March. Here’s the updated version:

Benefits

- If the firm survives the bankruptcy process intact, it has a higher probability of being viable in the long run (than in a restructuring outside of bankruptcy).

- If the firm survives restructuring, the taxpayer has a higher probability of being repaid.

- Old equity holders faced the full costs of the firm’s failure (by being wiped out). No additional moral hazard is created.

Costs

- There are still significant risks to GM’s survival:

- Will GM and the Administration defeat the objecting unsecured creditors in court? (however unfair that might be)

- Will the bankruptcy process conclude quickly (within 90 days)?

- Will GM continue to lose market share? Can GM make cars and trucks that people want to buy?

- Will the new fuel economy and emissions rules restrict GM’s ability to make attractive vehicles?

- This is a big new cash outlay from the taxpayer. This costs the taxpayer, and further constrains available TARP funds.

The President made clear his answer to this question on March 30th. At that time he laid out the conditions under which he would provide additional funding, and those conditions were met. No one should be surprised that he is now putting more taxpayer funding at risk. I am surprised that they only need $30 B.

My view: We crossed this bridge back in late March. It is not a new decision today to put more taxpayer funding at risk. I don’t like it, but I am at least glad that some incentives have been restored: the firm has to go through a bankruptcy process, shareholders are wiped out, and management was fired. I remember arguments from last fall and earlier this year that GM should get more taxpayer dollars outside of a bankruptcy process. That would have been far worse, and today’s actions mitigate some moral hazard.

Given the relative strength of the U.S. economy now compared to last December, I would have preferred an outcome of a pre-packaged bankruptcy + private DIP financing, and not exposing taxpayers to any additional risk. If GM is really as viable as GM and the President claim it now is, then they should have no problem convincing capital markets to provide them with short-term financing. (Judge Richard Posner argues this.) I will guess that this was not actually a viable option, because the pre-packaging could only come together with the direct involvement of the government. I think the real options would have been expose taxpayers to $30B more risk, or allow GM to liquidate. I would go with the latter: if GM can’t find private financing, they’re on their own. I assume this means they would liquidate. This would have been harsh and painful for those affected. I believe the consequences of further intervention now are worse for a larger number of people in the long run.

3. Is the pre-packaged bankruptcy likely to succeed?

There are two components to this question:

- Is the bankruptcy process likely to be quick and successful?

- Will the resulting company succeed without additional taxpayer aid?

I do not feel well-qualified to comment on the first question. The talking heads all repeat that “GM’s bankruptcy is more complicated than Chrysler’s,” with little detail about why. I would point out that the Administration is one for one in this process. Their use of this part of the bankruptcy code (section 363), and the process where the old GM sells the good stuff to a new GM, and then the remaining parts are liquidated, appears to have worked for Chrysler. From my perspective, the burden of proof now shifts to those who argue this bankruptcy will take more than 90 days. I didn’t like it because of the precedent it set, but I wouldn’t bet against the Administration succeeding again.

Other than the “good for GM is good for America” quote, the biggest surprise in the President’s remarks was how heavily he was betting that a restructured GM will succeed. He could easily have taken the posture, “GM has made some hard decisions, and they have a tough road ahead if they want to survive and succeed.” Instead, he attached his own credibility to GM’s future success and said:

So I’m confident that the steps I’m announcing today will mark the end of an old GM, and the beginning of a new GM; a new GM that can produce the high-quality, safe, and fuel-efficient cars of tomorrow; that can lead America towards an energy independent future; and that is once more a symbol of America’s success.

Even with a cleaned up balance sheet and more taxpayer funding, it is by no means certain that GM will survive for the long run. If GM fails in the next few years, the taxpayers will have lost an additional $30.1 B that the President committed today. In addition, the above quote will come back to haunt the President. I understand wanting to set a positive and optimistic tone. I am confused why he did so at such great political risk to himself.

I found it useful to return to my first post on the autos and review what this new pre-packaged bankruptcy + DIP financing does to the wide range of challenges faced by GM:

Revenues

- The economic slowdown means fewer vehicles are being purchased from all auto manufacturers, foreign and domestic.

- Even apart from the economic slowdown, U.S. auto manufacturers have been losing market share over time.

- This is in part because they made a bet on light trucks versus smaller cars. This product mix doesn’t work when gas prices are high. Think of the proliferation of SUVs in the past 10 years. (Note that this was in part the fault of U.S. government policies. SUVs are technically light trucks, and so they qualify for lower fuel economy requirements.)

Costs & productivity

- The Detroit 3’s ongoing labor costs are higher than those of foreign-based firms. This is still true when you compare an American worker in a GM plant in Michigan, for instance, with an American worker in a Nissan plant in Mississippi.

- Productivity is lower in U.S. plants of U.S. firms than it is in U.S. plants of foreign-based firms. Some of this is because of the UAW contract that mandates certain inefficiencies. Some of it is poor management.

- The Detroit 3 have huge dealer networks that are costly to the manufacturers. These dealer franchises are often protected by state laws that make it hard for the manufacturers to make these networks smaller and more efficient.

- Auto manufacturers face a burdensome and unpredictable legislative and regulatory environment.

Balance sheets

- The Detroit 3 have enormous legacy costs from their retirees. Past UAW contracts provided generous benefits that continue to burden these firms. This drains profits (when they earn them) away from productivity-enhancing investments.

So can GM survive, and for how long? Can they profit and flourish, as the President suggests they will?

- The Administration and GM argue that a restructured GM can break even in a national market of only 10m vehicles sold in America each year. (We’re now around 9.5m/year. “Normal” is around 16m/year.) If accurate, this is astonishing.This would appear to address all three of the bullets under revenues. Addressed? I’m skeptical. I need to review the assumptions in GM’s new plan, especially about market share.

- I have seen no evidence that GM and UAW have reduced significantly GM’s ongoing labor costs to be competitive with the transplants. Maybe I have missed it. Unaddressed.

- Productivity is still lower in U.S. plants of U.S. firms that it is in U.S. plants of foreign-based firms. As a result of high compensation costs per worker and low productivity, it appears that labor cost per vehicle produced will still be uncompetitive with the transplants. Unaddressed.

- GM’s dealer network is being dramatically reduced. Addressed.

- The CAFE and emissions requirements are even more burdensome than predicted, but now have at least some degree of stability, given the national standards. On net, worse than before.

- The balance sheets will be relieved of enormous debt and legacy health and pension obligations. Addressed.

My view: I need to look more at what GM is assuming for market share. The removal of the legacy obligations, combined with a big chunk of taxpayer change, will buy then many months of survival.

The Administration is stressing the balance sheet improvements, and they deserve credit for that. Conservative critics focus on the additional burdens of the fuel economy and emissions rules, and they’re right, too.

I would focus even more on the questions asked by several commenters: “Will people want to buy GM cars and trucks?” Additionally, can GM make a profit with still high labor costs, still low productivity, still burdensome work rules, and still slow product development cycles?

I want to GM to survive and be profitable in the long run. Their chances are now drastically improved, assuming they survive bankruptcy. But I don’t know if that’s an improvement from a 1% chance to a 20% chance, or from a 1% chance to an 80% chance. A lot more needs to change beyond just cleaning up the balance sheet, and many of those needed changes are deep-seated in the culture, structures, and processes of America’s third-largest company.

4. Is the pre-packaged bankruptcy fair?

Absolutely not. But I want to be precise in my criticism.

The easiest thing to do in Washington is to criticize the negotiator. “I could have gotten a better deal,” we say. I should begin my expressing my sympathy and offering my congratulations to Steven Rattner and the Obama team for closing what was undoubtedly a complex and difficult set of negotiations. I’m sure this one was not easy, and theirs was a thankless task.

At the same time, I share the concerns of many that the deal was not even-handed, and that the precedent will damage future business lending. I have grave concerns about how far they were willing to stretch bankruptcy processes and the traditional capital structure to get a deal.

First I need to correct the Administration, as well as some bad reporting today by the Washington Post. In last night’s background briefing for the press, an unnamed Senior Administration Official claimed (emphasis added):

Secondly, as you know, the UAW has reached a new agreement with GM and that agreement has been ratified that involves significant concessions by the UAW … concessions that are in virtually every respect more aggressive than what the previous administration demanded in its loan agreement.

In the term sheet for the December loan we (the Bush Administration) made to General Motors, we set out “targets,” which we took directly from the Corker amendment offered the week prior on the Senate floor:

- Reduce outstanding unsecured debt by not less than 2/3 through conversion into equity or other debt;

- Reduce the total amount of compensation, including wages and benefits, paid to their U.S. employees so that, by no later than December 31, 2009, the average of such total amount, per hour and per person, is an amount that is competitive with the average total amount of such compensation, as certified by the Secretary of Labor, paid per hour and per person to employees of Nissan Motor Company, Toyota Motor Corporation, or American Honda Motor Company whose site of employment is in the United States.

- Eliminate the jobs bank.

- Apply work rules no later than 12/31/09 “in a manner that is competitive with Nissan … Toyota or Honda in the U.S.”

- Not less than half of their VEBA payment should be in the form of stock.

As best I can tell:

- They more than accomplished target #1.

- They did little to nothing on #2. I have seen no evidence that compensation of current workers has been changed. UAW Chief Ron Gettelfinger claimed in a message to his members, “For our active members these tentative changes mean no loss in your base hourly pay, no reduction in your health care, and no reduction in pensions.” Maybe there’s a distinction between this statement and “total compensation.” If so, it would be great if someone could help me understand this. But it appears GM and UAW did nothing to address target #2.

- UAW agreed to #3 in late March.

- They made no apparent progress on target #4. I have neither seen nor heard evidence that the work rules have been relaxed. I am happy to be corrected.

- They accomplished #5.

It was incorrect for the Senior Administration Official to call these “demands” of the Bush Administration. They were targets, not hard conditions. It is an overstatement to say that they “are in virtually every respect more aggressive than what the previous Administration demanded,” unless “virtually every respect” means “except for compensation and work rules.” (I am happy to be corrected if I have just missed the changes.)

The Washington Post then further flubbed it by writing:

Critics say it is unfair that the restructuring plan gives the union health trust a larger share of the new GM than the bondholders. But administration officials defend the plan, offering several justifications.

First, they note that the terms of the proposed GM restructuring echo the terms laid out by the Bush administration in December, when it extended $13.4 billion in loans to GM.

The Bush administration’s loan agreement required a 50 percent reduction or “haircut” for the union trust, but a 66 percent cut for the bondholders. The Obama deal requires larger cuts for both sides, though more for the bondholders.

The agreement does more than meet three of the five targets laid out by the Administration. It appears to make no progress on the other two targets. Thus the terms do not “echo the terms laid out by the Bush administration in December.”

More importantly, the targets we (Bush team) laid out said nothing about the distribution of equity shares. The criticism is not that the deal doesn’t cut the VEBA enough, or reduce unsecured debt enough. The criticism is that someone lower in the capital structure (UAW’s VEBA) got a much greater equity share than someone higher in the structure (unsecured creditors). It is disingenuous to point to the targets in the Bush Administration’s December loans to justify this inequity.