House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan released his proposed budget resolution today. As I’ve done in the past I’m going to compare his proposal to the President’s budget. I’d like to include Senate Budget Committee Chairman Patty Murray’s proposal but she has chosen not to do a budget this year.

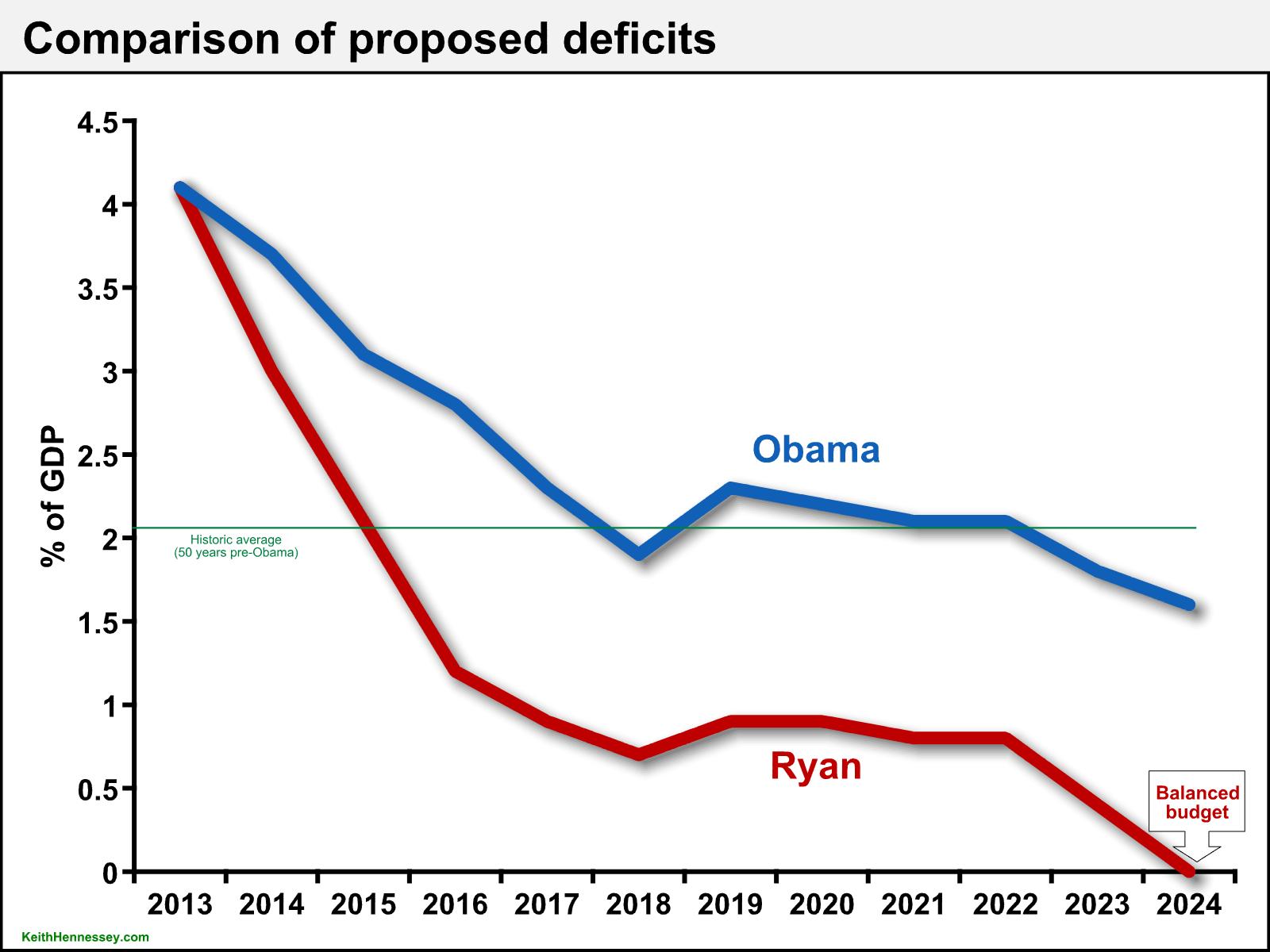

In this post I’m just going to compare the short-term deficit and debt effects of the two proposals. While I’d like to use comparable numbers, CBO has not yet rescored President Obama’s proposal because the President released his budget six weeks late. So for now I’ll compare Ryan’s numbers to Obama’s. That is suboptimal but the best we can do for now, and I am confident it doesn’t change the overall picture. Let’s start with deficits.

A few things jump out.

- Chairman Ryan’s deficits are lower than President Obama’s throughout the budget window.

- The difference is significant in the early years.

- President Obama’s budget would reduce deficits below their historic average only after he leaves office.

- The gap between the two stabilizes around 1.5 percentage points of GDP.

- Chairman Ryan’s budget gets to balance, President Obama’s does not.

The most politically potent aspect is balance vs. no balance.

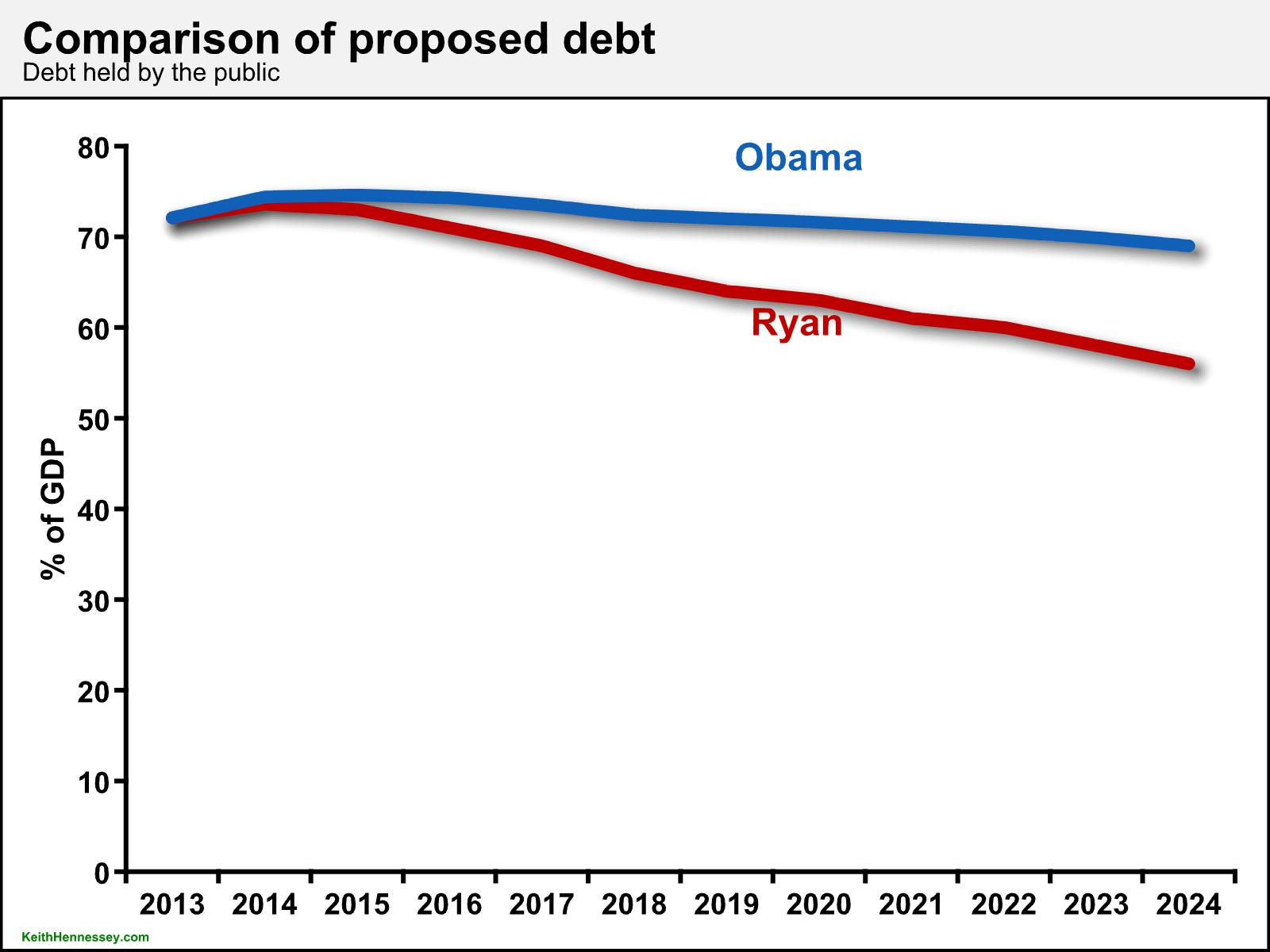

Now let’s compare the short-term debt effects of the Ryan and Obama budgets. Debt held by the public is (sort of) the accumulation of past deficits and a few surpluses.

- Both propose to reduce debt/GDP over the next decade.

- Chairman Ryan’s debt is in all cases lower than the President’s.

- Over time the difference is significant: Ryan’s 10th year level is 13 percentage points lower than Obama’s (caveat: This will change a bit when we get the CBO rescore of the President’s budget).

The notable points here are (1) the growing gap over time and (2) the President’s decision to reduce debt/GDP over time, albeit slowly. In past years he was content to stabilize debt/GDP in the short run.

Fiscal politics and strategy

At first glance the Obama and Ryan budgets appear quite similar to what each proposed last year. Because the downward slope is so gentle, President Obama’s declining debt/GDP path is more significant politically than as a policy matter. It allows him to say his budget would reduce debt over time, at least in the short run. He couldn’t say that last year.

In this midterm election year, Chairman Ryan has offered House Republicans a tremendous political advantage: BALANCE. This reminds me of 2011.

The two political parties have traditionally competed over which party was “the party of lower deficits and less debt.” Many elected officials and their campaign advisors have traditionally seen significant political advantage in labeling their opponents as being for higher deficits and more debt.

This debate is somewhat silly, as the principal fiscal policy difference between the two parties has usually been more about the size of government than about which party wants to borrow less from the future. Nevertheless, the political effects of deficit/debt comparisons are significant.

The same is true for a balanced budget. The economic difference between balance and a 1 percent deficit is not dramatically different from the difference between a 1 and a 2 percent deficit. But the politics of a balanced budget can be powerful.

In 2011 President Obama proposed his budget in February. Chairman Ryan then proposed a budget with a significantly more aggressive deficit and debt reduction path, thus seizing the political advantage in this partisan competition. The numbers clearly showed that (House) Republicans were for much lower deficits and debt than the President.

And then the President modified his budget in April, proposing significantly lower deficits than he did two months prior. He purported to match the deficit reduction in the Ryan budget–this was a lie, but he claimed it. (See Bob Woodward’s book for details on both the internal process and the lie.) What’s significant today is that in 2011 President Obama reacted to the political weakness he then faced by being for higher deficits and debt than House Republicans. He proposed more policy changes, some of which involved more political pain, just so the could claim to match House Republicans on deficits and debt.

Fast forward three years. It’s happening again.

Chairman Ryan has teed up a significant political tool for House Republicans: they can be for a balanced budget, in contrast both to President Obama’s higher deficits and debt and to the Senate Democrats’ lack of a budget.

This is a potent weapon for the mid-term election battle. Congressional Republicans can be not just opposed to something unpopular (Obamacare, of course), but for something popular. They can expand their topline economic message to have three legs rather than just one.

<

ol>

I’ll end with three important strategy questions:

- Are House Republicans a governing majority? Ryan’s balanced budget provides a political advantage only if House Republicans pass it. Can Chairman Ryan and Boehner/Cantor/McCarthy find 218 R votes for the Ryan budget?

- Will Republicans recognize the political and rhetorical advantage that a balanced budget gives them and integrate it into their core election message, putting it on a level playing field with both “weak Obama recovery” and Obamacare? Or will they bet all their mid-term election prospects on a single issue?

- Will President Obama react to House passage by modifying his budget proposal as he did in 2011? Or will he cede the rhetorical high ground on deficits, debt, and a balanced budget in favor of attacking the details within the Ryan budget?