The Obama Administration is trumpeting that the budget deficit has been cut by half, “the largest four-year reduction since the demobilization from World War II.” Indeed, CBO projects the deficit this year will be 3 percent, maybe dropping a few tenths over the next few years before beginning an inexorable climb driven by demographics, health cost growth, and unsustainable entitlement benefit promises to seniors. If you listen to the President, our only problem is that future one and that’s a few years off. Now that deficits have come down, he says we’re OK for the time being. Deficits around 3 percent will hold debt constant relative to the size of the U.S. economy, and he appears to think that’s fine.

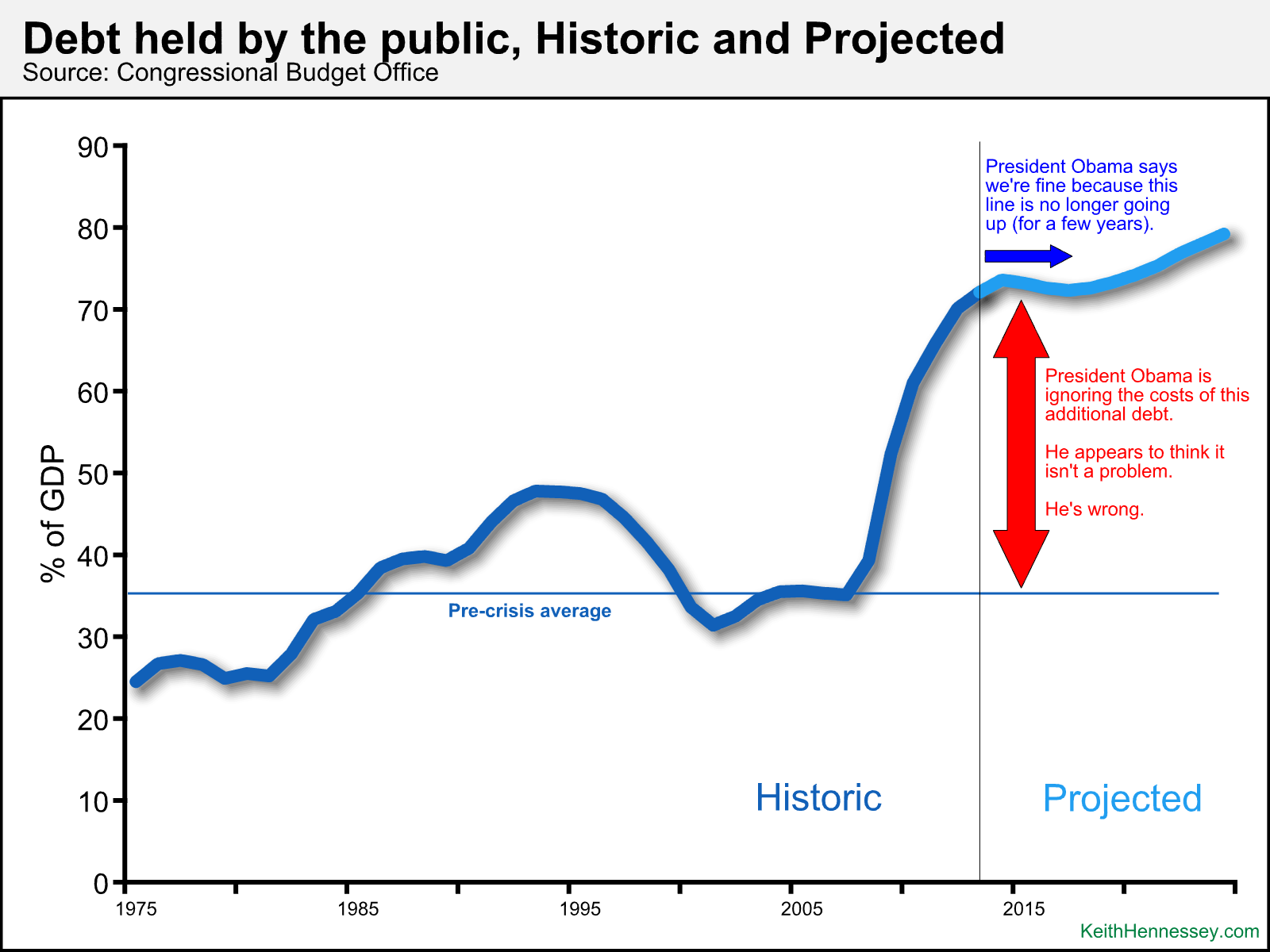

I don’t. Look at this graph from CBO.

In their recently released annual Economic and Budget Outlook CBO lays out the four costs of higher debt (page 7).

- “Federal spending on interest payments will increase substantially as interest rates rise to more typical levels;”

- “Because federal borrowing generally reduces national saving, the capital stock and wages will be smaller than if debt was lower;”

- “Lawmakers would have less flexibility … to respond to unanticipated challenges;”

- “A large debt poses a greater risk of precipitating a fiscal crisis, during which investors would lose so much confidence in the government’s ability to manage its budget that the government would be unable to borrow at affordable rates.”

CBO attributes these damaging effects to “high and rising debt,” and doesn’t distinguish between high (where we are now, in the mid 70s as a share of GDP) and future entitlement spending-driven growth. The same logic applies both to today’s high debt and to future even higher debt. These are real and significant costs we are bearing today.

It’s obvious that we can’t allow debt to increase forever as it will begin to do a few years from now but there’s an additional important question that is being largely ignored. Momentarily setting aside future projected debt growth, is debt/GDP in the mid-70s acceptable? Should the goal be to not let the problem get worse, or both to solve the future debt growth and, over time, to reduce debt/GDP to be closer to the historic pre-crisis average?

CBO has done policymakers a great service by explaining these four costs of high and rising debt, and I wish more members of Congress understood them and talked about them. This is important enough that it’s worth the time to understand it well. You can find a slightly expanded version from CBO on pages 9 and 10 here.

I want to expand a bit on CBO’s points. I’ll take them in reverse order and start with the last one, the increased risk of a fiscal crisis. Those on the left who argue that high debt isn’t a problem like to (a) pretend that this increased risk is the only consequence of high debt, and then (b) dispute that the higher risk is significant enough to cause concern. I worry that when the U.S. has doubled its debt/GDP in five years, and when our future debt path looks like it does, that the risk of a fiscal crisis is significant. But this risk is unknowable, and even if we could somehow measure this risk, we can never know when that crisis would occur. My stronger arguments are (1) fiscal crisis risk is undoubtedly higher at a higher debt level; (2) the risk is only going to increase on our current path as debt increases; and (3) there are three other costs to higher debt, so even if you’re not worried about crisis risk, you need to address those other costs.

Moving up the list we get to CBO’s “less flexibility” point. CBO’s projected debt path assumes a (very) slow but basically steady return to macroeconomic health. If we have another recession, terrorist attack, or war, the numbers will be worse, and whatever increased government spending or fiscal stimulus we will then need will be initiated from a much weaker starting point (a much higher level of debt). Because our debt is so high we are poorly prepared to address future risks that require significant short-term deficit spending or tax relief.

Then we get to the cost with the greatest political impact: lower future wages. This is really a cost of the big recent deficits that resulted in today’s higher debt, and an additional cost of projected future deficit growth. The reduced national saving caused by big deficits leads to a smaller capital stock. This lowers productivity and therefore wages. To reduce our public debt government would have to save more (or even, perish the thought, balance the budget), leading to higher national saving, a bigger capital stock, higher productivity and higher future wages. To be politically crass: lower government debt means more shiny new factories with high wage American jobs. I’m willing to sacrifice quite a lot of government spending in exchange for higher future wages.

Finally, the item at the top of CBO’s list is the one most likely to drive Congressional action. Our government debt is now 37 percentage points above its pre-crisis average, but government interest payments are relatively low because interest rates are low because the short-term economy is still weak. When the economy eventually recovers and the government debt rolls over, that additional debt is going to increase government net interest payments by about 1.85 percent of GDP (37% X CBO’s 5% 10-year Treasury rate). Relative to the rest of the federal budget, 1.85% of GDP is enormous. That increased interest cost is as much as the federal government will spend this year on all military personnel (uniformed + civilian) plus all science, space, and technology research plus all spending on the environment, conservation, national parks, and natural resources plus all spending on highways, airports, bridges, and all other transportation infrastructure. Higher debt means higher interest costs which will squeeze out spending for other things that government does. It will also increase pressure to raise taxes even further.

Government debt is twice as large a share of the economy as it was before the financial crisis. In addition to increasing the risk of another catastrophic financial crisis, high government debt squeezes out other functions of government, creates pressure for higher taxes, leaves policymakers less able to respond to future recessions, wars, and terrorist attacks, and lowers future wage growth. This problem will only increase as entitlement spending growth kicks into high gear a few years from now, but simply stabilizing debt/GDP in the mid 70s is an insufficient goal. Don’t rest on your laurels because deficits are smaller than they used to be. High government debt is a big problem.