The President and Budget Director Peter Orszag frequently say we need to “bend the health care cost curve downward” to address our long-term fiscal problems. This is correct but incomplete.

Here is Director Orszag, writing in last week’s Financial Times: (emphasis added)

As the healthcare debate picks up in the US, there has been much discussion about how to pay for it. Coinciding with this debate are vocal concerns about the country’s underlying fiscal position … which some have suggested as a reason to delay healthcare reform.

What this argument ignores is that healthcare is central to the long-term fiscal and economic prospects of the US. If costs per enrollee in Medicare and Medicaid grow at the same rate over the next four decades as they have over the past four, those two programmes will increase from 5 per cent of gross domestic product today to 20 per cent by 2050.

Healthcare cost growth dwarfs any of the other long-term fiscal challenges the US faces. Nothing else we do on the fiscal front will matter much if we fail to address rapidly rising healthcare costs.

Director Orszag is correct that rising per-capita health spending is a key driver of our long-term fiscal problems. But he overstates his case by ignoring the other driver of federal spending growth, demographics. We need to address both. We need health care reform that will slow the growth of per capita health spending. And we need to change the promises made under Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid to adjust for a rapidly aging U.S. population.

Let’s look at a graph from the President’s Budget (page 191 of the Analytical Perspectives volume):

This chart shows the combined effects on the big three entitlement programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security) of two factors: demographics, and age-adjusted per capita health cost growth. The effect of demographics is larger than the effect of “excess growth in health care costs” up until some time in the 2040s. This is why Director Orszag chooses 2050 to make his case.

Director Orszag’s own graph shows that the aging of the population is a bigger driver of spending increases in the federal budget for the next 30-40 years.

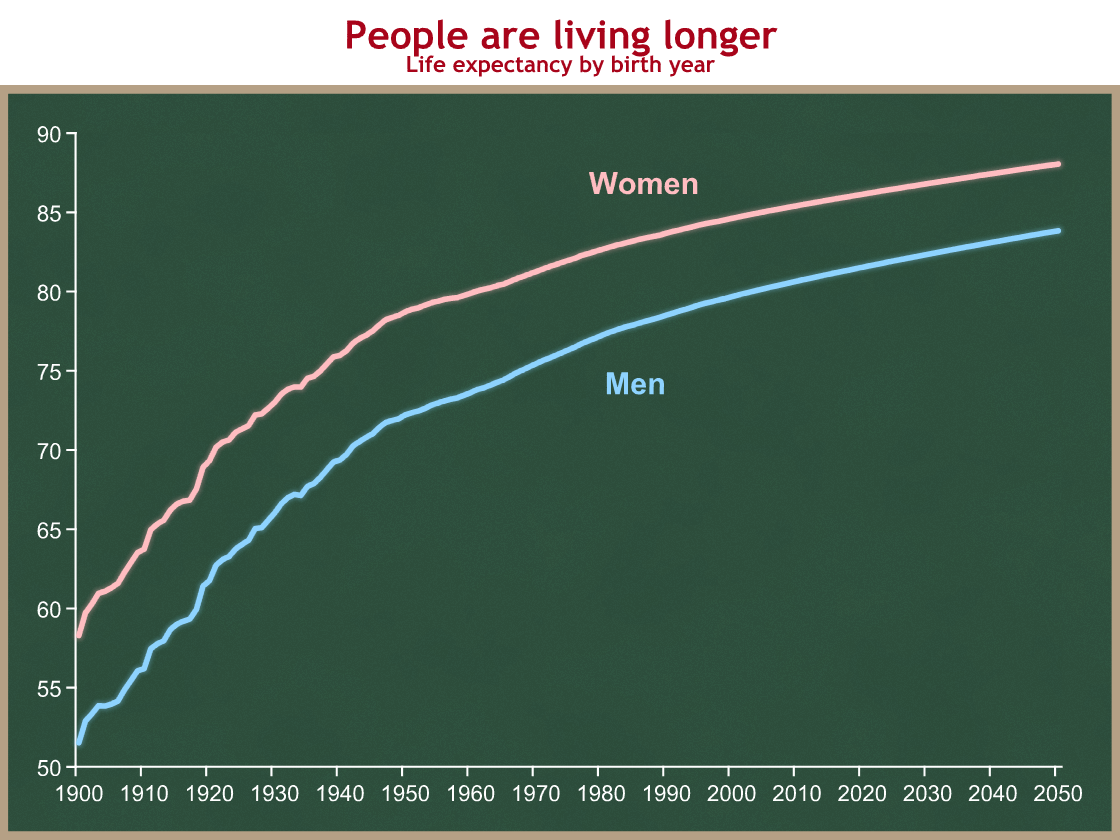

There are two forces driving the aging of the U.S. population. People are living longer. This is a good thing.

This means people are collecting benefits for more years. That’s good for people and expensive for the government.

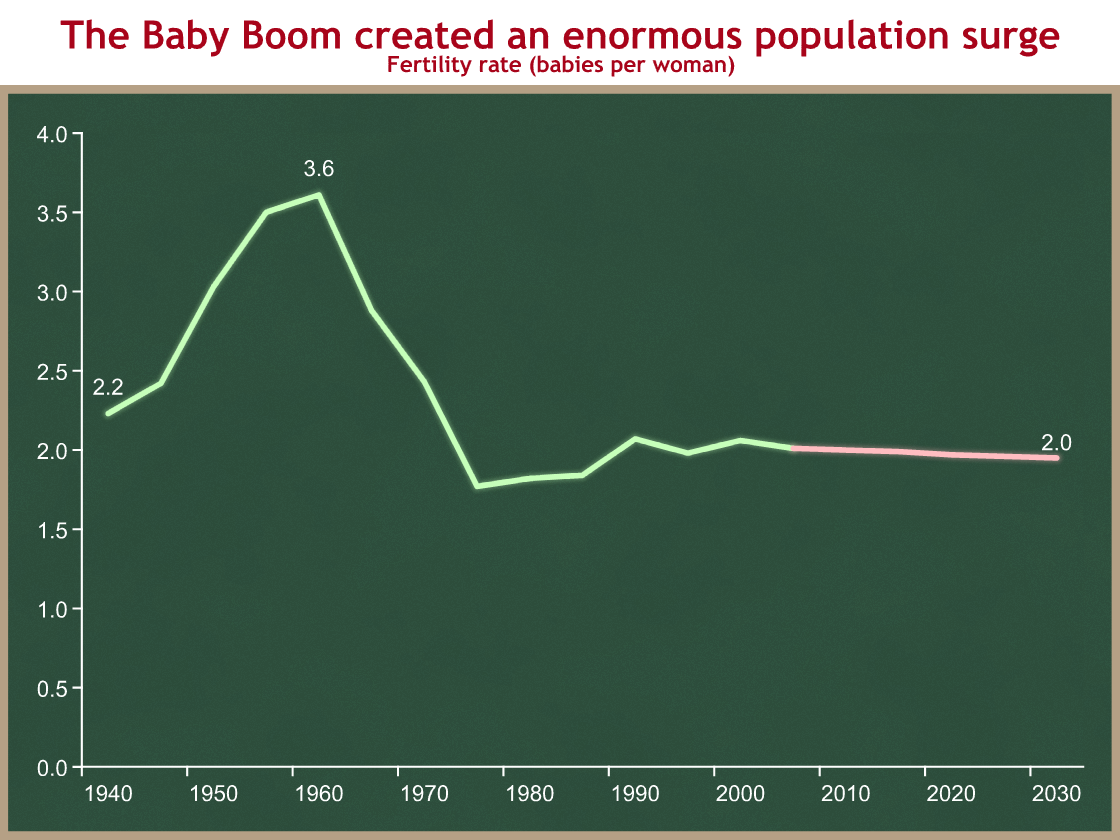

Longer life expectancies are a permanent and positive feature of the U.S. demographic landscape. There is a second, transitory cause of the aging of the U.S. population: the Baby Boom. Fertility rates surged after World War II. Before and during the war, each woman had on average about 2.2 – 2.4 babies. That surged to 3.6 babies per woman in 1960, and is now down to 2.0, where it is predicted to stay.

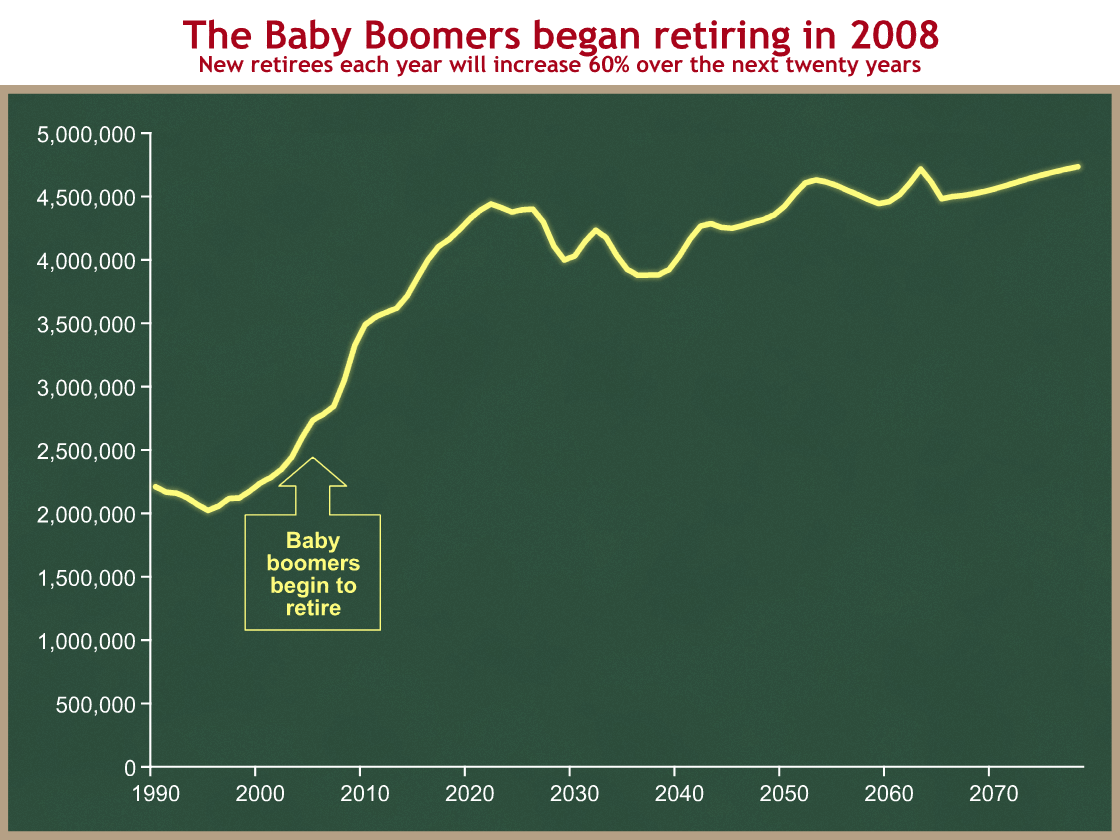

The Baby Boom began in 1946. You can start collecting early retirement benefits under Social Security at age 62. This means the first cohort of Baby Boomers started collecting their checks in 2008. You can see how the number of new retirees each year is going to spike over the next ten years.

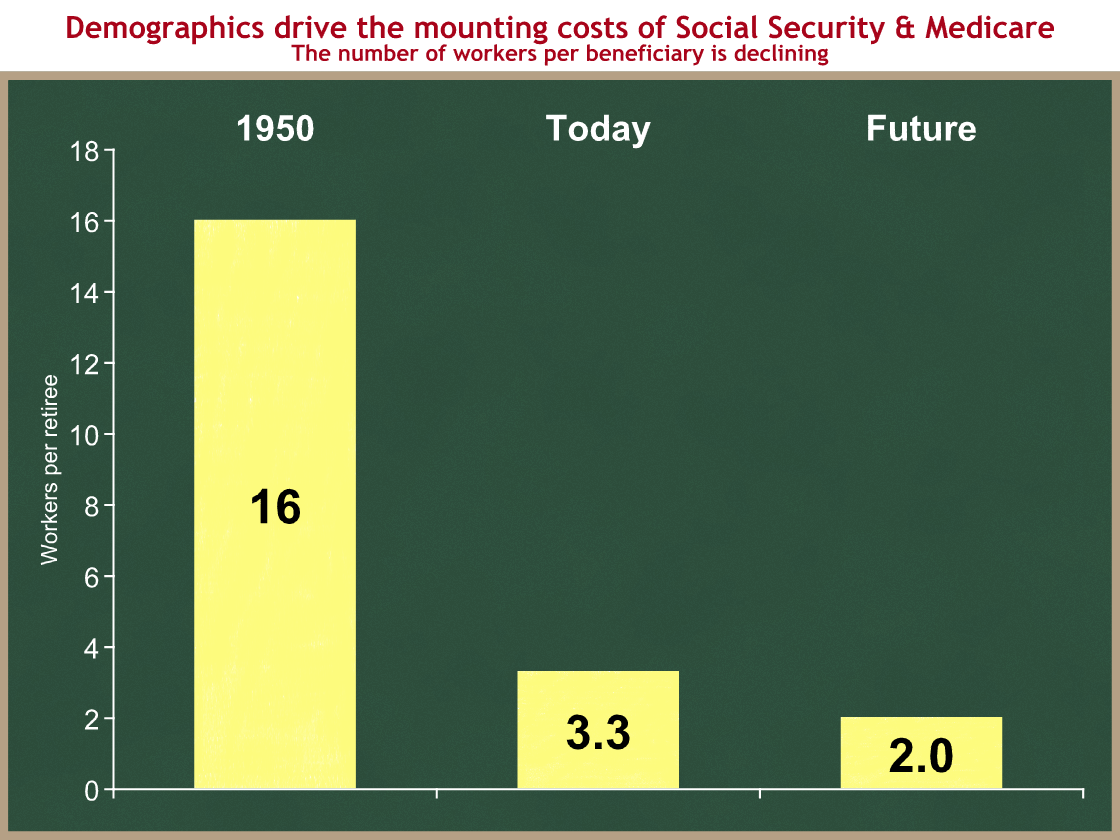

I think of longer lifespans as a permanently rising tide, and the Baby Boom as a huge wave that supplements that tide. Together, the two of them mean that America is rapidly aging. This is affecting federal and state budgets beginning now. Since Social Security and Medicare are pay-as-you-go systems, in which current workers pay for the benefits of current retirees, this means a larger tax burden is placed on each younger worker. (No, the government does not save your payroll taxes. It has spent and is spending them on other stuff.)

In 1950, there were 16 workers paying payroll taxes for each retiree collecting Social Security benefits. Today, there are 3.3 workers supporting the Social Security and Medicare benefits of each retiree. In the future there will be only 2 workers paying taxes to support the benefits of each retiree.

The rapid growth of per capita health spending in the U.S. is a critical policy problem that needs to be addressed. It is not, however, the primary driver of our federal budget problems over the next 30-40 years. The aging of the population is. Policy changes need to address both pressures to prevent an eventual fiscal meltdown. We must not ignore demographics.